ABSTRACT

This study aimed to compare the efficacy of nimotuzumab (Nimo) versus cetuximab (C225) plus concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) in locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (LA-ESCC). A total of 95 patients with LA-ESCC were retrospectively reviewed, including 65 in Nimo and 30 in C225. The results showed that the ORR in Nimo (61.0%; CR 22.0%, 13/59; PR 39.0% 23/59) was slightly higher than that in C225 (43.5%; CR 8.7%, 2/23; PR 34.8%, 8/23) but without significant difference (p = 0.81). The DCR was 79.7% vs. 73.9% in C225, favoring Nimo plus CCRT (p = 0.04). The median PFS in Nimo was significantly longer than that in C225 (19.6 months vs. 13.0 months, p = 0.02). The median OS of the whole cohort, the Nimo group and the C225 group were 21.3, 24.5, and 20.9 months, respectively. The rates of OS at 1-, 3-year in Nimo were 77.7% and 33.5%, compared to 73.3% and 20.0% in C225 (HR = 1.17, p = 0.23). Grade 3 or worse hematological toxicity and non-hematological toxicity (radiation esophagitis) in Nimo were similar with that in C225 (21.5% vs. 26.7%, p = 0.91; 26.1% vs. 26.7%, p = 0.56). No grade ≥3 radiation pneumonitis occurred neither Nimo group nor C225 group. Nimo plus CCRT improved DCR and PFS of patients with LA-ESCC and had a tendency of prolonged survival compared to C225 plus CCRT. Our results suggest that the combination of Nimo and CCRT may be a reasonable option in this population.

KEYWORDS: Esophageal cancer, nimotuzumab, cetuximab, EGFR, chemoradiotherapy, targeted therapy, survival

Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) is the third most common malignancy and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in China.1 Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is the predominant type of EC, accounting for about 90% of cases worldwide and 68.3% for Asian.2,3 More than half of the cases were in the localized or regional disease at diagnosis, preventing radical surgery delivery.2 Concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) has become the standard practice owing to the better clinical outcomes in contrast to sequential or separate chemo/radiation in the treatment of locally advanced (LA-) ESCC. However, the 5-year survival rate of 23.4% is still poor despite the advance of chemotherapy regimens and radiotherapy technique.2 Consequently, combining novel therapeutics to further improve survival is an urgent task.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), binding its ligand EGF as a type I transmembrane protein, plays an important role in the process of tumorigenesis, differentiation, invasion, and development.4,5 Previous studies have demonstrated that EGFR was amplified and overexpressed approximately 50% in ESCC.6,7 Moreover, amplified EGFR gene was a negative prognostic factor for ESCC (p = 0.015).8 Therefore, the cooperation of CCRT and anti-EGFR may be a potential approach to improve the efficacy and further translate into clinical benefits. However, data from randomized trials showed that the efficacy of cetuximab (C225), a recombinant human/mouse chimeric monoclonal antibody (mAb), remained controversial and even contradictory in ESCC.9–11 In contrast, Nimotuzumab (Nimo), the first humanized anti-EGFR mAb, showed promising efficacy in combination with CRT in EC.12–15 A phase I study showed the complete response (CR) rate was 50% and treatment-related toxicities were well tolerable in stage II-IV EC patients treated with Nimo plus CRT.12 A better response (p = 0.02) and a tendency of prolonged survival (median survival time [MST], 15.9 months vs. 11.5 months, p = 0.09) in the Nimo plus CRT arm compared to the CRT alone arm were also reported in a randomized phase II study.15 The differences in the affinity on EGF and pathways and other possible mechanisms make it possible for Nimo to be more promising than C225 in triple therapy of EC.16–18

In view of the excellent performance of C225 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, the combination of anti-EGFR and chemoradiation in ESCC should not be easily abandoned. Hence, it is urgently needed to evaluate the efficacy of Nimo in ESCC compared with other anti-EGFR drugs. To date, however, there is no head-to-head study to compare the efficacy of Nimo and C225 in combination with CCRT in LA-ESCC. We collected data in the real world to preliminarily investigate the clinical outcomes of Nimo and C225 in patients with LA-ESCC undergoing CCRT. This study not only indicates the superior of Nimo, compared to C225, on disease control, progression-free survival (PFS), and treatment-induced toxicities, and provides a potential promising EGFR-targeted agent, but also makes it possible to further study the cooperation of anti-EGFR plus CCRT in this population.

Patients and methods

Patients

The patients with ESCC diagnosed by cytology or histopathology who had complete clinical data and follow-up information, including age, gender, tumor stage, tumor location, and records of PFS, overall survival (OS), were collected in this retrospective study between 2013 and 2017. All patients who had undergone any anti-tumor therapy before targeted therapy plus CCRT or with other primary tumor were excluded. In addition, the patients with aged > 75 years or KPS < 70 were likewise excluded. Systematic evaluation before treatment was performed, including complete blood count, contrast-enhanced chest and abdominal computed tomography (CT), cervical CT or supraclavicular ultrasound, or positron emission tomography (PET)/-CT. All patients were staged according to the criteria of AJCC 7th edition. Locally advanced stage was defined clinical T3-4N1, T4N0, and N2/N3 with any T stage but without distant metastasis. As ultrasound endoscopy (EUS) is not routinely used in our cancer center, T/N staging was mainly diagnosed according to CT or PET/CT due to few patients were given EUS. The level of EGFR expression, EGFR, KRAS, and NRAS mutations were not tested in all of the patients.

This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of our cancer center. All participants or their legal guardians provided informed consent.

Treatment

Nimo was given intravenously with a dosage of 200 mg at the first day per week in the period of radiation. Similarly, C225 was given intravenously once a week with a dosage of 400mg/m2 for the first time followed by 250mg/m2 for the subsequent weeks. Promethazine 25 mg i.m. was given 30 min before C225 infusion. Chemotherapy was delivered on the first day of radiation given. The regimens consisted of cisplatin (75mg/m2 on day 1) and taxanes with two cycles every 3 weeks, and the additional two cycles of chemotherapy were given after the completion of radiotherapy. As a retrospective study, the patients with the first cycle of chemotherapy or targeted therapy given within one week before or after the first day of radiotherapy were also eligible. Radiotherapy was delivered at a dose of 1.8–2.0 Gy once daily on 5 days weekly for 6–7 weeks up to a total dose of 50.4–64 Gy in 3D-CRT or IMRT technique. The gross tumor volume was defined as primary tumor and involved lymph nodes indicated by imaging study. The clinical target volume (CTV) consisted of CTVt, defined as GTV for the primary tumor plus a 3–5 cm margin craniocaudally and 0.8 −1.0 cm margin laterally, and CTVnd, defined as GTV for lymph nodes plus a 0.5–1.0 cm radial margin. The planning target volume was generated by CTV plus 0.5 cm radially.

Follow-up

Patients were followed up every 3 months for the first year after the completion of whole chemotherapy and every 6 months for the next three years, and annually thereafter. A complete history and physical examination, complete blood count, comprehensive chemistry profile, and contrast-enhanced CT scan of the chest and abdomen, with or without supraclavicular lymph nodes ultrasound, were performed for the follow-up evaluations. Other examinations were conducted if clinically indicated.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 22.0 statistical analysis software (IBM Corp., Armonk, Ny, USA) was performed to analyze all data in the current study. Chi-square (Fisher’s exact) were performed to compare the clinical characteristics and toxicities of two groups. OS was measured from the diagnosis to the date of any caused death or to the last known date of follow-up. PFS was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of disease progression or death from any cause, or to the date of censor. Treatment response was evaluated according to the response evaluation criteria in solid tumors version 1.1. Adverse events were evaluated and graded according to National Cancer Institute’s Common Toxicity Criteria version 4.03. Kaplan-Meier method was used to evaluate the OS and PFS. Log-rank test was used to compare the difference between the two groups. Further evaluation was carried out using Cox’s regression model. All p values were two-tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patients

Between 2013 and 2017, 3885 patients were diagnosed with EC, including ESCC and other subtypes. Among of them, 652 patients were diagnosed with LA-ESCC, including 132 patients who underwent CCRT plus C225 or Nimo and the rest 520 patients underwent sequential chemoradiotherapy or CCRT without targeted therapy. Of 132 patients, 17 patients lost, 13 patients had no informed consent, and 7 patients aged ≥ 75 years old. Consequently, a total of 95 patients were finally enrolled in this retrospective study, including 82 males and 13 females. The clinical features of the 95 patients in this study were summarized in Table 1. The median age for the whole cohort is 60 years (range, 40–74 years), whereas it was 60 years (range, 40–72 years) in Nimo and 59 years (range, 45–74 years) in C225. A total of 91.6% (87/95) of patients underwent complete CCRT plus targeted therapy, while 68.7% (60/87) in Nimo and 31.0% (27/87) in C225. In addition, the patients who underwent chemotherapy plus Nimo within one week before or after the first day of radiotherapy were 21 (35.0%), while it was 8 (29.6%) in C225 (p = 0.81). The reasons for 8 patients who did not complete CCRT plus targeted therapy were as follows: four patients for grade ≥ 3 radiation-induced esophagitis (3 in Nimo, 1 in C225), one patient for cardiac event (C225), two patients for declined KPS (C225), and one patient for refusal (Nimo).

Table 1.

Clinical features of 95 patients with LA-ESCC treated with CCRT plus nimotuzumab (Nimo) or cetuximab (C225).

| Nimo (n = 65) | C225 (n = 30) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 58 (89.2%) | 24 (80.0%) | 0.22 |

| Female | 7 (10.8%) | 6 (20.0%) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≥ 60 | 31 (47.7%) | 12 (40.0%) | 0.87 |

| < 60 | 34 (52.3%) | 18 (60.0%) | |

| T stage | |||

| T1-3 | 36 (55.4%) | 18 (60.0%) | 0.67 |

| T4 | 29 (44.6%) | 12 (40.0%) | |

| N stage | |||

| N0-1 | 13 (20.0%) | 3 (10.0%) | 0.44 |

| N2 | 37 (56.9%) | 18 (60.0%) | |

| N3 | 15 (23.1%) | 9 (30.0%) | |

| Location | |||

| Upper | 11 (16.9%) | 9 (30.0%) | 0.26 |

| Middle | 28 (43.1%) | 13 (43.3%) | |

| Lower | 26 (40.0%) | 8 (26.7%) | |

| RT technique | |||

| 3D-CRT | 10 (15.4%) | 3 (10.0%) | 0.75 |

| IMRT | 55 (84.6%) | 27 (90.0%) |

Efficacy

The efficacy of the two groups for treatment strategies was listed in Table 2. According to the records of patients in the current study, a total of 82 patients (59 in Nimo, 23 in C225) were evaluable for treatment response. The overall response rate (ORR) was 61.0% (95% CI: 0.49–0.73) in Nimo (CR 22.0%, PR 39.0%), which was higher than 43.5% (95% CI: 0.23–0.64) in C225 (CR 8.7%, PR 34.8%) but without significant difference (p = 0.15). However, the disease control rate (DCR) was slightly higher in Nimo compared to that of C225 group (79.7% vs. 73.9%, p = 0.04).

Table 2.

Efficacy of treatment for the nimotuzumab (Nimo) group and C225 group.

| Nimo (n = 59) | C225 (n = 23) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete response (CR) | 13 (22.0%) | 2 (8.7%) | |

| Partial response (PR) | 23 (39.0%) | 8 (34.8%) | |

| Stable disease (SD) | 18 (30.5%) | 7 (30.4%) | |

| Progression disease (PD) | 5 (8.5%) | 6 (26.1%) | |

| Objective response (CR+PR) | 36 (61.0%) | 10 (43.5%) | 0.15 |

| Disease control rate (CR+PR+SD) | 54 (91.5%) | 17 (73.9%) | 0.04 |

Survival

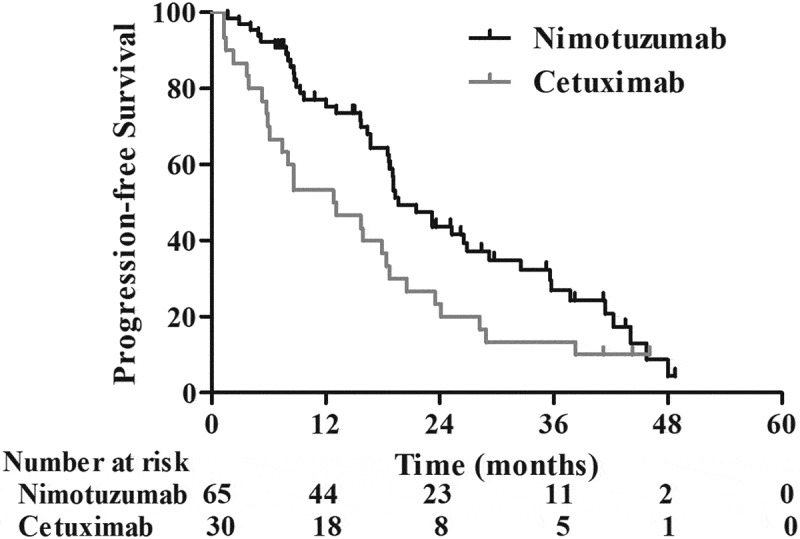

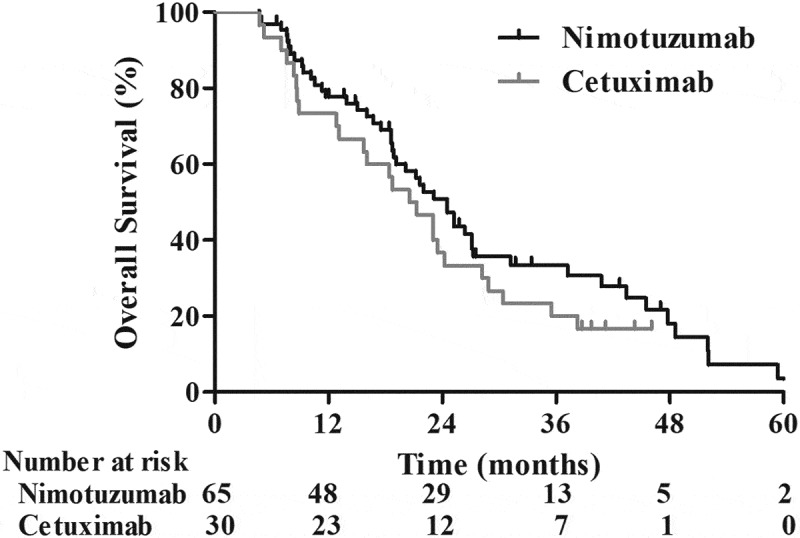

The median time of follow-up was 28 months (range, 4.9–74 months) for the whole cohort. To the end of follow-up, 23.2% (22/95) of patients were still alive. The median PFS for the entire group is 18.7 months. As indicated in Figure 1, the median PFS in the Nimo group is significantly longer than that in the C225 group (19.6 vs. 13.0 months, p = 0.02). The 1- and 2-year PFS rates were 75.3% and 43.7% in the Nimo group, which was significantly higher than 53.3% and 23.3% in the C225 group. The MST for the entire group was 21.3 months, whereas it was 24.5 months in Nimo, and 20.9 months in C225. The 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival rates were 77.7%, 50.9%, and 33.5%, respectively, in the Nimo group compared to 73.3%, 36.7%, and 20.0%, respectively, in the C225 group (HR = 1.17, p = 0.23) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival of patients treated with nimotuzumab (n = 65) versus. C225 (n = 30) plus CCRT.

Figure 2.

Overall survival of patients treated with nimotuzumab (n = 65) or C225 (n = 30) plus CCRT.

A total of 76.8% (73/95) of patients died, including 93.2% (68/73) died of tumor progression and 6.8% (5/73) died of nontumor-related causes. Among the five patients, one died from pneumonia, two died from cardiovascular disease, and the rest two patients died from cerebrovascular accident. Due to the high proportion of tumor-related death, no cancer specific survival was calculated in the present study. In addition, three patients ultimately died from fistula (one esophagotracheal fistula [Nimo], two mediastinoesophageal fistula [C225, Nimo]).

Toxicity

Table 3 summarizes the main hematologic and non-hematologic adverse events of the two groups. All patients in the two groups occurred at least grade 1 hematologic toxicities. Grade 2 hematologic toxicities were the most common AEs and occurred in 50.8% of the Nimo group and 40.0% of the C225 group. Grade ≥ 3 leukopenia, neutrophil count decreased and anemia in Nimo were lower than that in C225 but without significant difference (p = 0.27, 0.33 and 0.55, respectively). The morbidity of Grade ≥ 2 or ≥ 3 radiation esophagitis in Nimo was no significant difference compared to that in C225 (64.6% vs. 76.7%, p = 0.24; 26.1% vs. 26.7%, p = 0.96). No grade ≥ 3 radiation-induced pneumonitis occurred in both two groups, while the grade 2 radiation-induced pneumonitis was similar in the two groups (13.8% [Nimo] vs. 16.7% [C225], p = 0.72). No diarrhea and rash needed the intervention occurred in both two groups. No treatment-related deaths occurred in the period of CCRT plus targeted therapy.

Table 3.

Treatment-related adverse events in the nimotuzumab (Nimo) group and the Cetuximab (C225) group.

| Nimo (n = 65) | C225 (n = 30) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hematological toxicities | |||

| Grade 1 | 15 (27.7%) | 10 (33.3%) | |

| Grade 2 | 33 (50.8%) | 12 (40.0%) | |

| Grade 3 | 14 (18.5%) | 7 (23.3%) | 0.91 |

| Grade 4 | 2 (3.1%) | 1 (3.3%) | |

| Leukopenia ≥ 3 | 11 (16.9%) | 8 (26.7%) | 0.27 |

| Neutrophil count decreased ≥ 3 | 8 (12.3%) | 6 (20.0%) | 0.33 |

| Anemia ≥ 3 | 9 (13.8%) | 6 (20.0%) | 0.55 |

| Radiation-induced pneumonitis | |||

| Grade 2 | 9 (13.8%) | 5 (16.7%) | 0.72 |

| Grade 3–4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Radiation-induced esophagitis | |||

| Grade 1 | 23 (35.4%) | 7 (23.3%) | |

| Grade 2 | 25 (38.5%) | 15 (50.0%) | |

| Grade 3 | 16 (24.6%) | 8 (26.7%) | 0.96 |

| Grade 4 | 1 (1.5%) | 0 |

Discussion

As one of transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase (RTKs), EGFR binding its ligands through the extracellular domain by heterodimerization or homodimerization induces the activation of downstream pathways such as RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/TOR to promote tumorigenesis.19,20 According to block overexpressed EGFR in tumor cells, C225 and Nimo could provide potential therapeutics in ESCC. However, the difference in affinity, bind regions or other unclear mechanisms between Nimo and C225 may contribute the inconsonant or even inconsistent clinical profiles on adverse events, treatment response and survival.17,21–24

Anti-EGFR therapy indeed achieved an excellent efficacy in ESCC. A phase II study of C225 plus CCRT indicated 72% of ESCC patients achieved CR.25 Another multicenter phase II trial also illustrated 97.7% of 45 evaluable LA-ESCC patients had clinical response (64.4% CR, 33.3% PR).9 For Nimo, a study from Japan enrolled 10 patients with stage II–IV treated with Nimo plus CCRT and showed that ORR is 62.5% while the CR rate is 50.0%.12 Another small sample phase I study from China indicated 22% (2/9) reached CR, 56% (5/9) partial response, yielding 78% ORR in LA-ESCC.14 The latest NICE trial, conducted to assess the safety and efficacy of chemoradiation combined with Nimo in patients with inoperable locally advanced esophageal cancer (93% squamous cell carcinoma), revealed the combined endoscopic CR and pathologic CR in Nimo were significantly higher than that in patients without Nimo (62.3% vs. 37.0%, p = 0.02).15 To our current knowledge, no study has been conducted to compare the efficacy of Nimo and C225 in EC. In our study, it was consistent with previous studies that ORR was 61.0% in Nimo and DCR was 91.5%. However, it was only 43.5% and 73.9% in C225 accordingly. It was noted that ORR was obviously higher in Nimo than that in C225 even without significant difference (p = 0.15). DCR was beside higher in Nimo than that in C225 (p = 0.04). We speculated the difference was owing to the higher CR in Nim compared to that in C225. However, it should be considered cautiously due to the marginal effect. Furthermore, the lower ORR and DCR in C225 were also speculated being caused by the insufficient evaluable patients (76.7%, 23/30) in a small sample retrospective study.

However, the great response did not completely translate into survival benefits. Despite high 2-year PFS (74.78%) and OS (80.00%) rates in a prospective multicenter phase II study conducted by our cancer center, no MST was calculated after follow-up 36 months.9 RTOG 0436 was designed to evaluate the benefit of C225 added to CCRT for patients with inoperable EC.11 The results revealed that additional C225 to CCRT have no advantage for 2-year survival rate compared to the CCRT arm (45% vs. 44%, p = 0.47). SCOPE-1 trial investigated the additional C225 to cisplatin and fluoropyrimidine-based definitive chemoradiotherapy in LA-EC, which includes 72.9% (188/258) squamous cell carcinoma. The MST was only 22.1 months in the CCRT plus C225 group, which was significantly lower than that 25.4 months in the CCRT group (p = 0.043).26 Although long-term results from updated SCOPE-1 indicated no statistical difference existed on survival between C225 plus CCRT group and CCRT alone group, the MST in C225 plus CCRT group decreased compared to CCRT group (24.7 months vs. 34.5 months, p = 0.137).27 Consistent with their results, the benefits of C225 plus CCRT in the present study were disappointing and the MST and 2-year survival rate were 20.9 months and 36.7%, respectively. These randomized trials failed to demonstrate the benefit of the addition of C225 to CCRT. The pivotal reasons that lead them to lose might be account of unselected patients. Neither of RTOG0436 and SCOPE-1 test KRAS and its downstream pathway proteins mutations. But in contrast, 50 patient samples in Meng et al study were tested for KRAS and no positive mutation was determined. Furthermore, only ESCC were collected in Meng et al study but adenocarcinoma or other types of EC were included in RTOG 0436 and SCOPE-1. In addition, the higher radiation dose of 59.4 Gy/33 fractions in Meng et al study compared to 50Gy/25 fractions in SCOPE-1 and 50.4Gy/28 fractions in RTOG 0436 might also contribute to the success of the study. Consequently, targeting EGFR combined with CCRT in EC still hold a promising efficacy, just selecting appropriate patients and exploring more potential mechanisms to resist activated downstream pathway or enhance anti-EGFR efficacy.

Nimo as a humanized monoclonal anti-EGFR antibody has more potential than C225 for the treatment of LA-EC with combined chemoradiotherapy. Basic study demonstrated Nimo promoted radio-sensitivity of EGFR-overexpression ESCC by upregulating IGFBP-328 Perez et al pointed out that the biological characteristics that differ from other monoclonal antibodies might induce Nimo to produce different clinical effects through different pathways.16 Moreover, antitumor efficacy of Nimo was not impacted by KRAS status in pancreatic cancer cells in vivo.18 Furthermore, the addition of Nimo to chemotherapy/radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy was well-tolerant. A phase I dose escalation study of Nimo plus CCRT in LA-ESCC indicated Nimo of 400 mg/week delivered with CCRT was well-tolerant and no dose-limiting toxicities were observed.14 Another phase I study from Japan also showed Nimo plus CCRT was tolerable and the maximum-tolerated dose was at least 200 mg/week delivered.12 In the current study, hematologic toxicities, such as leukopenia (16.9%), neutrophil count decreased (12.3%), and anemia (13.8%), and grade ≥ 3 radiation-induced esophagitis (26.1%) in Nimo was acceptable.

The encouraging data on treatment response and survival for Nimo further supported its use in clinic. Nimo 200 mg/week, combined to cisplatin and paclitaxel, was used as first-line treatment in local-regional and advanced ESCC in a phase II study.29 ORR was 51.8% and DCR was 92.9%. For local-regional advanced disease, the median duration of disease control time is 23.0 months, and OS was not reached. In NICE trial, the cEPCR was significantly higher in the Nimo group (62.3%) in contrast of 37.0% in the CRT alone group (p = 0.02).15 Similarly, the MST is longer in Nimo (15.9 vs. 11.5 months), regardless of none significant difference (p = 0.09). The data from the real world on the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic ESCC also illustrated that MST was prolonged in patients treated with Nimo (11.9 vs. 6.5 months, p = 0.004).30 Consistent with the previous study, this study showed an increased 3.5 months for MST in favor of the group of patients treated with Nimo compared to patients treated with C225.

In summary, the current study focused on comparing Nimo and C225 based on their clinical feasibility for the treatment of LA-ESCC. To our knowledge, no study has been conducted to compare Nivo vs. C225 plus CCRT in LA-ESCC. Our data showed that Nimo plus CCRT produced similar ORR, OS, and toxicities, but higher DCR and longer PFS, compared to C225 plus CCRT. This suggests that in clinic Nimo has the potential capability to translate into survival benefits. Preliminary clinical results showed better outcome achieved after nimotuzumab-based treatment in EC in the presence of high EGFR and low p-Akt expression.31 Consequently, not only EGFR but more biomarkers should be detected to screen more suitable populations for the treatment of anti-EGFR plus CCRT.

However, this retrospective study has a few inevitable limitations. The sample size is small that no propensity score-matched analysis could be performed, that makes confounding factors not be excluded completely. Other important factors, such as tobacco and alcohol use, were not collected. In addition, no precision T/N stage was stated due to the absence of EUS. Third, we were unable to figure out the criteria of C225 or Nivo chosen in clinical. As a consequence, objective bias was not excluded. The biological effects of two different antibodies on EC may vary and warrant further study to explore the interaction of EGFR and other potential associated factors, particularly to explore EGFR expression, the phosphorylation of EGFR or its downstream pathways, such as KRAS, PI3K, etc., and the remaining members of the ERBB family (Her2, Her3, and Her4). However, no further detection could be conducted in this study due to insufficient samples obtained by biopsy. This study has not been able to present a standard criterion to guide the clinical selection of C225 or Nivo. However, according to the present study, the potential benefits of Nivo for survival make it valuable to further study the screening populations that are more appropriate for anti-EGFR therapy or to design more efficient monoclonal antibodies. Currently, a multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase III trial was conducted to investigate the efficacy of CCRT with or without Nimo in LA-ESCC (NCT02409186).32 We hope the randomized trial could solve the above problems.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Innovation Project of Shandong Academy of Medical Science and CSCO-SCORE [Grant Y-MT2015-012]CSCO-SCORE.

Disclosure of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Conflict of interest

None

References

- 1.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015 CA. Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, et al., eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute; 1975–2014. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/. Based on November 2016 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rustgi AK, El-Serag HB Esophageal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2499–2509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olayioye MA, Neve RM, Lane HA, Hynes NE. The ErbB signaling network: receptor heterodimerization in development and cancer. Embo J. 2000;19(13):3159–3167. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okawa T, Michaylira CZ, Kalabis J, Stairs DB, Nakagawa H, Andl CD, Johnstone CN, Klein-Szanto AJ, El-Deiry WS, Cukierman E, et al.. The functional interplay between EGFR overexpression, hTERT activation, and p53 mutation in esophageal epithelial cells with activation of stromal fibroblasts induces tumor development, invasion, and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2007;21(21):2788–2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sunpaweravong P, Sunpaweravong S, Puttawibul P, Mitarnun W, Zeng C, Baron AE, Franklin W, Said S, Varella-Garcia M Epidermal growth factor receptor and cyclin D1 are independently amplified and overexpressed in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131(2):111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanawa M, Suzuki S, Dobashi Y, Yamane T, Kono K, Enomoto N, Ooi A. EGFR protein overexpression and gene amplification in squamous cell carcinomas of the esophagus. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(5):1173–1180. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitagawa Y, Ueda M, Ando N, Ozawa S, Shimizu N, Kitajima M. Further evidence for prognostic significance of epidermal growth factor receptor gene amplification in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2(5):909–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meng X, Wang J, Sun X, Wang L, Ye M, Feng P, Zhu G, Lu Y, Han C, Zhu S, et al. Cetuximab in combination with chemoradiotherapy in Chinese patients with non-resectable, locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective, multicenter phase II trail. Radiother Oncol. 2013;109(2):275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ha HT, Griffith KA, Zalupski MM, Schuetze SM, Thomas DG, Lucas DR, Baker LH, Chugh R. Phase II trial of cetuximab in patients with metastatic or locally advanced soft tissue or bone sarcoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36(1):77–82. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31823a4970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suntharalingam M, Winter K, Ilson D, Dicker AP, Kachnic L, Konski A, Chakravarthy AB, Anker CJ, Thakrar H, Horiba N, et al. 2017. Effect of the Addition of Cetuximab to Paclitaxel, Cisplatin, and Radiation Therapy for Patients With Esophageal Cancer: the NRG Oncology RTOG 0436 Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 3(11):1520–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato K, Ura T, Koizumi W, Iwasa S, Katada C, Azuma M, Ishikura S, Nakao Y, Onuma H, Muro K. Nimotuzumab combined with concurrent chemoradiotherapy in Japanese patients with esophageal cancer. A Phase I Study Cancer Sci. 2018;109(3):785–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramos-Suzarte M, Lorenzo-Luaces P, Lazo NG, Perez ML, Soriano JL, Gonzalez CE, Hernadez IM, Albuerne YA, Moreno BP, Alvarez ES, et al Treatment of malignant, non-resectable, epithelial origin esophageal tumours with the humanized anti-epidermal growth factor antibody nimotuzumab combined with radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2012;13(8):600–605. doi: 10.4161/cbt.19849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao K, Hu X, Wu X, Fu X, Fan M, Jiang G. A phase I dose escalation study of Nimotuzumab in combination with concurrent chemoradiation for patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of esophagus. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30(4):1585–1590. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9517-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Castro Junior G, Segalla JG, de Azevedo SJ, Andrade CJ, Grabarz D, de Araujo Lima Franca B, Del Giglio A, Lazaretti NS, Alvares MN, Pedrini JL, et al.. A randomised phase II study of chemoradiotherapy with or without nimotuzumab in locally advanced oesophageal cancer. NICE Trial Eur J Cancer. 2018;88:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez R, Moreno E, Garrido G, Crombet T. EGFR-Targeting as a Biological Therapy. Understanding Nimotuzumab‘S Clinical Effects Cancers (Basel). 2011;3(2):2014–2031. doi: 10.3390/cancers3022014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger C, Krengel U, Stang E, Moreno E, Helene I. Nimotuzumab and cetuximab block ligand-independent EGF receptor signaling efficiently at different concentrations. J Immunother. 2011;34(7):550–555. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31822a5ca6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou C, Zhu L, Ji J, Ding F, Wang C, Cai Q, Yu Y, Zhu Z, Zhang J. EGFR High Expression, but not KRAS Status, Predicts Sensitivity of Pancreatic Cancer Cells to Nimotuzumab Treatment. In Vivo Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2017;17(1):89–97. doi: 10.2174/1568009616666161013101657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arteaga CL, Engelman JA. ERBB receptors: from oncogene discovery to basic science to mechanism-based cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(3):282–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomas A, Futter CE, Eden ER. EGF receptor trafficking: consequences for signaling and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24(1):26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrido G, Tikhomirov IA, Rabasa A, Yang E, Gracia E, Iznaga N, Fernandez LE, Crombet T, Kerbel RS, Perez R. Bivalent binding by intermediate affinity of nimotuzumab: a contribution to explain antibody clinical profile. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11(4):373–382. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.4.14097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talavera A, Friemann R, Gomez-Puerta S, Martinez-Fleites C, Garrido G, Rabasa A, Lopez-Requena A, Pupo A, Johansen RF, Sanchez O, et al Nimotuzumab, an antitumor antibody that targets the epidermal growth factor receptor, blocks ligand binding while permitting the active receptor conformation. Cancer Res. 2009;69(14):5851–5859. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li S, Schmitz KR, Jeffrey PD, Wiltzius JJ, Kussie P, Ferguson KM.. Structural basis for inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor by cetuximab. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(4):301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiner LM, Carter P. Tunable antibodies. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(5):556–557. doi: 10.1038/nbt0505-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safran H, Suntharalingam M, Dipetrillo T, Ng T, Doyle LA, Krasna M, Plette A, Evans D, Wanebo H, Akerman P, et al. Cetuximab with concurrent chemoradiation for esophagogastric cancer: assessment of toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70(2):391–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.07.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crosby T, Hurt CN, Falk S, Gollins S, Mukherjee S, Staffurth J, Ray R, Bashir N, Bridgewater JA, Geh JI, et al. 2013. Chemoradiotherapy with or without cetuximab in patients with oesophageal cancer (SCOPE1): a multicentre, phase 2/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 14(7):627–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cosby T, Hurt CN, Falk S, Gollins S, Staffurth J, Ray R, Bridgewater JA, Geh JI, Cunningham D, Blazeby J, et al. Long-term results and recurrence patterns from SCOPE-1: a phase II/III randomised trial of definitive chemoradiotherapy ± cetuximab in oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(6):709–716. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao L, He LR, Xi M, Cai MY, Shen JX, Li QQ, Liao YJ, Qian D, Feng ZZ, Zeng YX, et al. Nimotuzumab promotes radiosensitivity of EGFR-overexpression esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells by upregulating IGFBP-3. J Transl Med. 2012;10:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu M, Wang X, Shen L, Jia J, Gong J, Li J, Li J, Li Y, Zhang X, Lu Z, et al. Nimotuzumab plus paclitaxel and cisplatin as the first line treatment for advanced esophageal squamous cell cancer: A single centre prospective phase II trial. Cancer Sci. 2016;107(4):486–490. doi: 10.1111/cas.12894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saumell Y, Sanchez L, Gonzalez S, Ortiz R, Medina E, Galan Y, Lage A. Overall Survival of Patients with Locally Advanced or Metastatic Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Treated with Nimotuzumab in the Real. World Adv Ther. 2017;34(12):2638–2647. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0631-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang CY, Deng JY, Cai XW, Fu XL, Li Y, Zhou XY, Wu XH, Hu XC, Fan M, Xiang JQ, et al. 2015. High EGFR and low p-Akt expression is associated with better outcome after nimotuzumab-containing treatment in esophageal cancer patients: preliminary clinical result and testable hypothesis. Oncotarget. 6(21):18674–18682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ClinicalTrials.gov A Phase III Study of Nimotuzumab Plus Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy in Loco-regional Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02409186; 2018. [accessed 2018 June12].