Abstract

At the heart of forensic science is application of the scientific method and analytical approaches to answer questions central to solving a crime: Who, What, When, Where, and How. Forensic practitioners use fundamentals of chemistry and physics to examine evidence and infer its origin. In this regard, ecological researchers have had a significant impact on forensic science through the development and application of a specialized measurement technique—isotope analysis—for examining evidence. Here, we review the utility of isotope analysis in forensic settings from an ecological perspective, concentrating on work from the Americas completed within the last three decades. Our primary focus is on combining plant and animal physiological models with isotope analyses for source inference. Examples of the forensic application of isotopes—including stable isotopes, radiogenic isotopes, and radioisotopes—span from cotton used in counterfeit bills to anthrax shipped through the U.S. Postal Service, and from beer adulterated with cheap adjuncts to human remains discovered in shallow graves. Recent methodological developments and the generation of isotope landscapes, or isoscapes, for data interpretation promise that isotope analysis will be a useful tool in ecological and forensic studies for decades to come.

Keywords: Criminal investigation, drug, food and beverage, human remains, wildlife

INTRODUCTION

Forensic science is defined as “the application of scientific knowledge and procedures in criminal investigations” (Oxford English Dictionary 1824). In practical terms, forensic science helps answer questions of Who, What, When, Where, and How a crime was committed through the examination of evidence (Inman and Rudin 2002). There are many types of forensic evidence, including analytical evidence, digital evidence, and experiential evidence (National Research Council (U.S.) 2009). Some fundamental approaches used by forensic practitioners for interpreting collected evidence are described below.

Basic Theories on the Interpretation of Evidence.

There are five fundamental concepts used in the interpretation of evidence, with a sixth suggested (Inman and Rudin 2002).

First, transfer, or Locard’s exchange principle, which asserts a perpetrator will bring something to the scene of a crime and also take something from it. Transfer can be summarized as the idea that “Every contact leaves a trace.”

Second, identification, or the categorization of evidence into class. Identification answers questions of What is it?

Third, individualization, or the reduction of possible evidentiary classes to one. Individualization answers the questions: Which one is it? or Whose is it?

Fourth, association, or an inference of contact between evidence “source” and “target.” Association links an individual to the scene of a crime.

Fifth, reconstruction, or the ordering of past events in time and space. Reconstruction answers questions of When, Where, and How.

Finally, matter division, or the understanding that transfer requires division of matter into smaller pieces. As part of this process, “the component parts will acquire characteristics created by the process of division itself and retain physico-chemical properties of the larger piece” (Inman and Rudin 2002).

Ecological Research and Forensic Evidence.

Most techniques used by forensic practitioners to collect analytical evidence originated in basic research efforts. A search of books, conference proceedings, and journals in Elsevier’s Scopus® database (www.scopus.com, accessed March 2017) of peer-reviewed literature for the term “forensic science” returns more than 18,000 results. The majority have been published by researchers in the United States, with the first printed around 1940.

Ecological researchers in particular have had an impact on forensic science through the development of isotope analysis techniques for organic material. Although isotope analysis is not yet a widely applied methodological approach in forensic science due to its relatively high cost, few commercial laboratories providing the service, and the specialized training needed to interpret the data, it is often used to augment other evidence examination methods as it can provide unique information. The technique allows investigators to compare items that appear chemically and physically identical but isotopically dissimilar. Applications of isotope analysis in plant and animal ecology, and subsequently forensic science, often capitalize on the observation that organisms act as recorders, storing information about their history in the isotopic signatures of their tissues (West et al. 2006).

Only 6% of the 18,000+ “forensic science” publications held by Scopus® can be liberally related to ecological research in the broad areas of agricultural and biological sciences, earth and planetary sciences, and environmental science. However, of the 44,000+ results generated by a search of Scopus® for the term “stable isotop*” (for “isotope” or “isotopic”), almost 90% come from ecological subject areas (which we note was very generously defined for the purposes of this literature search). A search of Scopus® returns more than 900 publications with both “forensic” and “isotop*” in the title, abstract, or keywords. Publication numbers decrease to ca. 300 when “forensic” and “stable isotop*” are used as search terms, with the first forensic stable isotope paper published in 1977.

Here we review the applications of isotope analysis in forensic settings from an ecological perspective. While sample-to-sample comparison of isotopic signatures can be useful in forensic science, we primarily focus on the interpretation of isotope data using plant and animal physiological models for source inference (Gentile et al. 2015). Reflecting the scope of published forensic isotope applications, the examples discussed here are limited to terrestrial ecology. We should also note that there has, to date, been a very limited role of isotopes in the prosecutorial phase of criminal investigations; most examples presented here emphasize the role of isotope analysis in the investigative phase.

Forensic uses of isotopes are generally restricted to the analysis and interpretation of isotopes at natural abundance levels and are therefore the focus of this review. Isotopic compositions of “bio-elements” are expressed throughout this work in delta (δ) notation, as the deviation of the ratio of the heavy to light isotopes (e.g., R = 2H/1H, 18O/16O) in a sample from a reference standard, in parts per thousand (‰): δ = (Rsample/Rstd − 1). Isotope abundances of the radiogenic element strontium are reported as Rsample, with no conversion to δ-notation – e.g., 87Sr/86Sr.

PLANT ISOTOPE RATIOS AS FORENSIC EVIDENCE

Carbon.

The photosynthetic pathway used by plants for C fixation affects the C stable isotope ratios (δ13C) of its tissues. Three different physiological processes are used by terrestrial plants for photosynthesis—C3, C4, and CAM—and differences in the initial photosynthetic carboxylation reactions result in large differences among the three pathways in δ13C values of plant tissues (Farquhar et al. 1989). The leaves of C3 plants are characterized by δ13C values of approximately −35‰ to −20‰ while the leaves of C4 and CAM plants are characterized by δ13C values of approximately −18‰ to −10‰ (Tipple and Pagani 2007). Following the initial formation of carbohydrates in a leaf, subsequent biochemical reactions can result in variations of 2-10‰ in the δ13C values of different plant compounds (e.g., carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins) and tissues (e.g., leaf, fruit, root, seed, etc.) (Badeck et al. 2005).

The δ13C values of plant tissues are affected by both the δ13C value of atmospheric CO2 and the isotopic fractionations associated with CO2 diffusion, C fixation, and respiration. During diffusion, observed fractionation is strongly linked to the ratio of the concentrations of CO2 at the sites of carboxylation (ci) and in the atmosphere outside the leaf (ca). In most growth environments, the δ13C value of atmospheric CO2 is relatively fixed; thus, variation in ci/ca causes the majority of C isotopic variability in terrestrial plants with these variations in turn related to light and water availability (O’Leary 1988; Farquhar et al. 1989).

Environmental conditions, including water stress, CO2 source, and light intensity, also affect plant tissue δ13C values. As an example, higher δ13C values are observed when plants are water stressed, primarily due to stomatal closure (Farquhar et al. 1989). These environmental effects cause the wide range of variation in δ13C values of C3 plants but have a smaller influence on δ13C values of C4 plants. Since some CAM plants are able to switch between CAM and C3 photosynthesis, the observed range of δ13C values of CAM plants is wide as well.

Nitrogen.

Interpreting plant nitrogen stable isotope ratios can be complicated, as plants may take in N directly through their roots, through associations with mycorrhizal fungi, or symbiotically through bacteria in root nodules. Most variations in the δ15N values of plant tissues are related to environmental variations in soil δ15N values. However, plant δ15N values can also vary between plant types and among plant tissues through physiological mechanisms involving assimilation of inorganic N and a clear dependence on mycorrhizal infection (Evans 2001). The δ15N values of nitrogen-fixing plants are well-defined, averaging approximately 0‰ (Craine et al. 2015), but with a relatively wide range as a result of variation in proportion of N fixed and fractionations associated with the fixation and transfer of N to the plant (West et al. 2005).

Excluding nitrogen-fixing plants, plant tissue δ15N values are additionally affected by soil (δ15N values. Soil and plant tissue (δ15N values generally decrease with increases in mean annual precipitation across large spatial scales. When mean annual temperature increases, δ15N values of soils and plant tissues typically increase as well (Amundson et al. 2003). In conditions that favor greater N cycling, the remaining N pool tends to be isotopically enriched. Soil N isotopic compositions also vary due to the application of fertilizers (Vitòria et al. 2004; Bateman and Kelly 2007; Craine et al. 2015). Most N found in fertilizer is derived efficiently and at high temperatures from atmospheric N2 via the Haber-Bosch process. As a consequence, δ15N values of inorganic fertilizers tend to be approximately 0‰, often distinct from soil N pools not derived from fertilizers (Bateman and Kelly 2007).

Hydrogen and Oxygen.

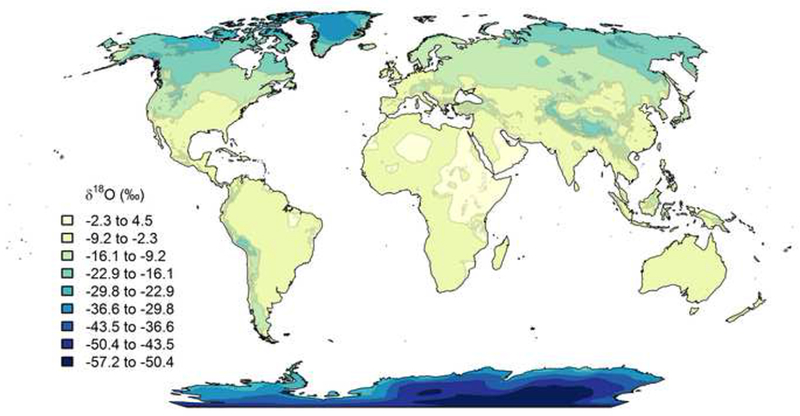

The δ2H and δ18O values of plant tissues are related to the isotopic composition of water. In general, xylem water δ2H and δ18O values reflect water available to the plant during growth because there is generally no isotopic fractionation during water uptake by roots (Ehleringer and Dawson 1992), although exceptions to this are observed (Ellsworth and Williams 2007). Environmental water δ2H and δ18O values are impacted by continentality (a measure of the ocean’s impact on the climate of a particular location), altitude, and latitude, with lower δ-values predictably found in cooler inland and high elevation/high latitude regions than in warmer coastal and low elevation/low latitude regions (Gat 1996; Bowen and Revenaugh 2003); see Figure 1. Leaf water is further modified as a result of evaporation and is generally enriched in the heavy isotopes relative to xylem water (Cernusak et al. 2016). It is in this environment that photosynthesis incorporates H and O into the organic compounds of leaf biomass and the building blocks of other plant tissues. These tissues are chemically complex with associated biochemical fractionations that alter their isotopic compositions, but generalizations can be made showing relationships between environmental water and plant tissue H and O isotopic compositions (Roden et al. 2000; Sachse et al. 2012).

Figure 1.

A spatial representation of global annual average precipitation δ18O values, estimated using the Online Isotopes in Precipitation Calculator (OIPC v3.0). Figure reprinted with permission. Copyright (2017) waterisotopes.org. This figure is available in color in the online version of the journal.

Note that some H atoms in organic materials, including many plant tissues, are not permanently bound to the material and thus free to interact with external water (exchangeable). These exchangeable H atoms need to be removed or accounted for when conducting H isotope analysis. There are multiple approaches to address and control for exchangeable H atoms (Carter and Chesson 2017a). Arguably the simplest, indirect approach is to equilibrate samples with laboratory air and then analyze all samples within a short period of time so that any effect of external water is comparable among samples. Additional approaches include determination of the δ2H value of only the non-exchangeable H atoms. This method for addressing H atom exchangeability has been used extensively in the analysis of animal tissues, such as hair keratin.

Sulfur.

In general, δ34S values decrease with increasing deposition of S from fossil fuel combustion (Krouse and Grinenko 1991). Soil δ34S values also vary along marine-to-inland gradients, with higher δ34S values seen near coastlines, a phenomenon often referred to as the “sea spray effect.” Seawater sulfate has δ34S values of approximately +21‰, a consequence of isotopic fractionation during bacterial reduction of sulfate to H2S in anaerobic waters (Thode 1991). In contrast, soil sulfate δ34S values are typically lower than about +10‰ while fertilizer δ34S values can range from −10‰ to +21‰ or higher (Vitòria et al. 2004).

FORENSIC APPLICATION OF PLANT ISOTOPE COMPOSITIONS

Counterfeit Currency.

One of the first uses of plant isotopic compositions for forensic intelligence purposes involved counterfeit currency. Between the late 1980s until 2000, high quality counterfeit US$100 notes were found circulating worldwide (Mihm 2006). The notes were so difficult to detect they prompted a redesign of the US$100 bill, which was introduced in 2013.

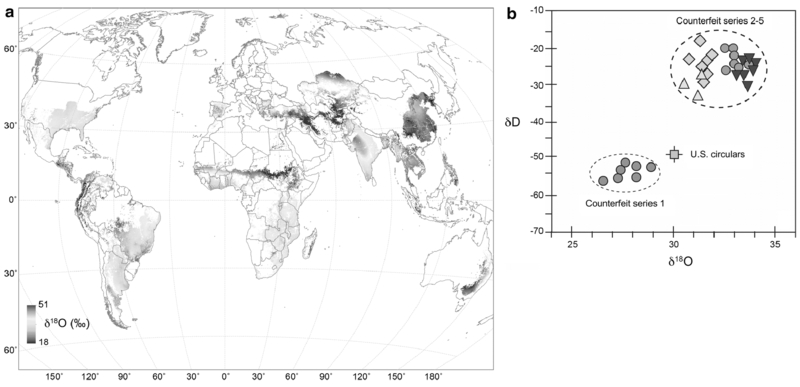

Like legal U.S. currency, the fraudulent notes were printed on mixed paper consisting of 75% cotton and 25% linen. Investigators measured the isotopic compositions of the paper used in printing both authentic and counterfeit currency to generate intelligence on potential growing region of plants used in the counterfeit paper. The δ2H and δ18O values of authentic bank notes were fairly homogenous (green square, Figure 2b), which is not surprising given that Crane & Co., the predominant supplier of paper for U.S. currency, sources its cotton from the southeastern quadrant of the continental U.S. (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

(a) Global map of predicted δ18O values of cotton based on leaf-water modeling coupled with local climate and δ18O values of local meteoric waters. Only regions where cotton is produced are shown. (b) A crossplot of δ2H (δD) and δ18O values of paper from genuine US$100 bank notes (green square) and high-quality counterfeit bank notes from multiple series. Figure reprinted with permission from Cerling et al. (2016a). Copyright (2016) Annual Reviews. This figure is available in color in the online version of the journal.

The δ2H and δ18O values of paper from fraudulent notes were significantly different from the authentic U.S. notes (Cerling et al. 2016a). Counterfeit notes from Series 1 were printed on paper made from cotton grown in cooler climate regions than the paper used for authentic U.S. notes, as reflected in the lower δ2H and δ18O values of the Series 1 notes. In contrast, counterfeit notes from Series 2-5 were printed on paper made from cotton grown in warmer climate regions than the authentic U.S. notes. It’s worth noting that this early research using H isotopes for investigating the source of the counterfeits did not directly address the presence of exchangeable H atoms in the paper. If it had, the degree of differences between paper δ2H values shown in Figure 2b could be greater than that observed, because exchangeable H atoms may have muted the actual source signal. To date, the origin of the counterfeits has not been positively confirmed, but the isotope data point toward multiple origins of the cotton used in its production; analysis helped to narrow the range of possible paper sources and clearly identified a shift in counterfeit paper sources over time.

Plant-Derived Drugs: Cocaine, Heroin, and Marijuana.

The stable isotope signatures of plant-derived illicit drugs have been used for years to provide source intelligence. One of the most successful efforts, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency’s (DEA’s) Cocaine Signature Program (CSP), got its start by combining trace alkaloid profiles with measurements of C and N stable isotope ratios of cocaine to link seized drugs to one of five coca-growing regions in South America (Ehleringer et al. 2000; Casale et al. 2005). At present, the program additionally uses H and O stable isotope ratios of cocaine with multivariate statistical analyses to classify cocaine from 19 growing regions within Bolivia, Colombia, and Peru (Mallette et al. 2016, 2017). The U.S. DEA’s Heroin Signature Program (HSP) has been developed in the same vein, using isotopic compositions alongside alkaloid profiles to source seized drugs to different poppy growing regions (Ehleringer et al. 1999; Casale et al. 2005, 2006). It should be noted that, to date, the isotope data collected in these programs has been used for investigative purposes and not criminal prosecution.

The U.S. DEA’s cocaine and heroin signature programs have been particularly successful due in part to the analysis of authentic cocaine and heroin samples from known source regions to construct isoscapes. It is also advantageous that coca and poppy are generally grown in discrete regions. However, recent seizures of coca plants in southernmost Mexico (Chiapas) suggest cocaine production is expanding outside South America, and additional growing regions may need to be considered by the CSP in the future (Casale and Mallette 2016).

Sometimes, the first hint of a new drug source comes when results of isotope and alkaloid content analyses of seized samples do not fit known region profiles (Casale et al. 2006; Mallette et al. 2016). In these cases, potential source inferences could be made using models of plant physiology and environmental effects on the isotopic compositions of plant tissues. Consider the seizure of cocaine from an aircraft drop in Uruguay, which had cocaine isotope ratios significantly different from authentic Bolivian samples previously measured within the CSP (Mallette et al. 2016). Lower δ13C values and higher (δ15N values of the seized cocaine suggested an origin at lower altitude and latitude, with reduced water stress, but increased mean annual temperature. Measured δ2H and δ18O values also suggested the coca plants had grown in a warmer area, at lower altitude or latitude. Investigators inferred that the cocaine originated from a more northern region than previous Bolivian cocaine samples, an interpretation that was supported by the plane’s departure point, Beni, Bolivia, which lies north of the Chapare Valley.

For plant-derived drugs such as marijuana (Cannabis sp.) that are grown widely across the globe and not in discrete regions, plant physiological models and predictions of environmental effects on plant tissue isotopic compositions are more crucial for source inference. Researchers from Brazil developed a linear discriminant analysis model for classifying the origin of unknown marijuana samples; they used C and N isotope ratios, which were related to climate and plant growth condition (Shibuya et al. 2006, 2007). Researchers from the University of Utah investigated the application of C and N stable isotope ratios—with the addition of H and Sr—to provide intelligence about the origin of marijuana seized on U.S. streets. A combination of δ13C and δ15N values was useful to infer the cultivation condition of cannabis plants (West et al. 2009b; Hurley et al. 2010a). Lower δ13C values were associated with growth indoors, where plants were both less likely to experience water stress and more likely to be supplied bottled CO2 of petrochemical sources with lower δ13C values than atmospheric CO2. A later study on the C stable isotope analysis of inflorescence waxes confirmed that δ13C values were lower in plants grown indoors (Tipple et al. 2016). Lower (δ15N values in marijuana inflorescence or leaf suggested the use of inorganic fertilizers (West et al. 2009b) as opposed to those supplied from animal and plant (“organic”) sources.

Measured Sr and H isotope ratios of cannabis plants were useful for providing intelligence about possible growth location (see later section on sources of spatial variation in Sr isotope ratios). The 87Sr/86Sr ratios of cannabis were correlated to the 87Sr/86Sr ratios of bedrock local to the area of plant growth (West et al. 2009a). Measured δ2H values were used to assign a marijuana sample to one of 16 U.S. regions (Hurley et al. 2010a), with lower δ2H values inferring a source location further inland, with a cooler climate and/or a higher latitude, based on the spatial distribution of δ2H values of water. When δ2H values were considered in combination with δ13C values, they could be used to infer the source of cannabis as from within or outside U.S. borders, and grown indoors or out (Hurley et al. 2010b). The usefulness of combined isotope measurements for investigating source was confirmed by a study that used H, C, N, and O stable isotope ratios of seized marijuana samples to monitor drug trafficking patterns in Alaska (Booth et al. 2010).

Plant-Derived Poison: Ricin.

Based on successful application of isotope analysis to source cotton paper and plant-derived drugs, a forensic investigator could expect the isotopic compositions of ricin, a poison derived from castor beans, would also be useful for sourcing. A combination of H, C, N, and O stable isotope ratios with 87Sr/86Sr ratios was shown to associate castor beans with growth location (Webb-Robertson et al. 2012). However, isotopes were more powerful for sample-to-sample comparison and discrimination; δ2H, δ13C, (δ15N, and δ18O values could be used to distinguish > 99% of ricin samples from all other ricin samples prepared using a similar method (Kreuzer et al. 2013).

Beverages: Beer and Wine.

Many high-value food products are derived from plants, and much of their value comes from the knowledge that a product was produced in a particular location or by a particular process. Manufacturers of authentic products have a vested interest in preventing fraud through misleading labeling by competitors. As such, while some law enforcement issues related to beverage fraud could be grounds for a criminal investigation, more often these misdeeds may be litigated as a civil lawsuit.

An early application of isotope analysis for product authentication purposes used 13C signatures of maple syrup and honey to verify that these C3-plant sweeteners had not been adulterated with cheaper C4-plant sugars (Doner and White 1977; Morselli and Baggett 1984; White 1992). The use of isotope analysis in food and beverage authentication has expanded greatly since these first studies on maple syrup and honey [see, for instance, (Carter and Chesson 2017b)]. As an example, we next consider the production of beer and sparkling wine.

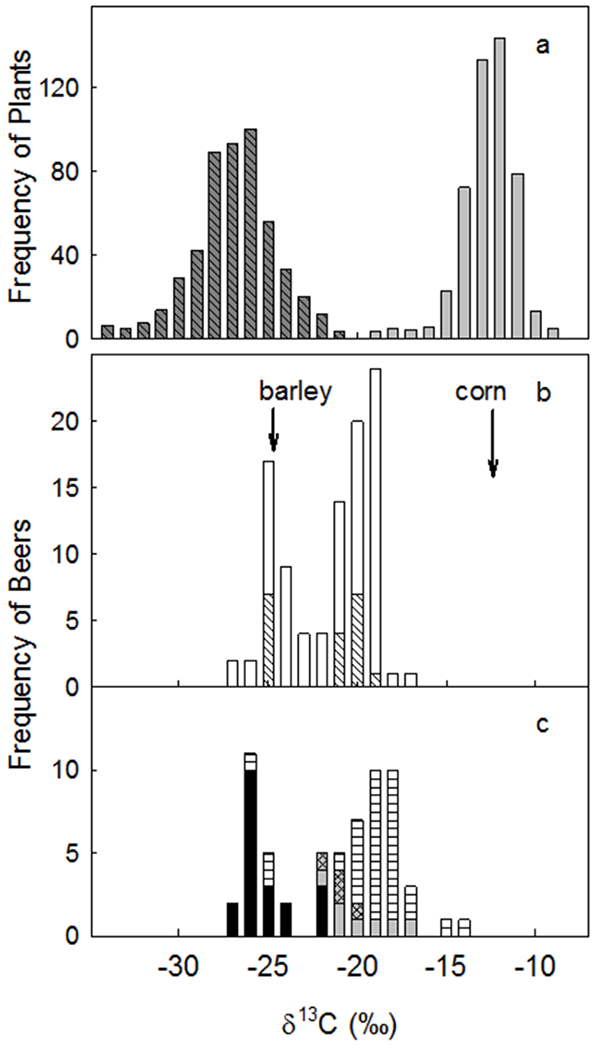

Four ingredients are traditionally used in brewing beer: water, malted barley, hops, and yeast. However, brewers are generally not required to list ingredients used, and few countries (the notable exception being Germany) have laws that specifically prohibit the use of other starches or sugars (“adjuncts”) in place of barley. Barley plants use C3 photosynthesis while com (maize), a cheaper grain, uses C4 photosynthesis. Because C3 and C4 plants are isotopically distinct, the δ13C value of evaporated beer residues should indicate whether substantial amounts of C4 sugar was used in brewing. In a survey of 160 beers from Canada, USA, Mexico, Brazil, Europe, and the Pacific Rim, measured δ13C values implied that 110 used a mixture of both C3 and C4 plant products in manufacture [Figure 3, (Brooks et al. 2002)]. Perhaps unsurprisingly, as the content of C4 sugars increased, the price of the beer decreased.

Figure 3.

(a) Absolute frequencies of carbon isotope ratios of C3 and C4 plants. (b) Absolute frequencies of carbon isotope ratios of beers brewed in the U.S and in Canada. (c) Absolute frequencies of carbon isotope ratios of beers brewed in Europe, Mexico, Brazil, and the Pacific Rim (Japan, Australia). Arrows indicate average δ13C values for two main beer ingredients, malted barley and corn sugar. Figure reprinted with permission from Brooks et al. (2002). Copyright (2002) American Chemical Society.

Three ingredients are used in sparkling wine production: cuvée (base wine derived from grapes), yeast, and sugars. Sparkling wine production typically includes two fermentation steps, the first providing ethanol in the cuvée and the second providing mainly carbonation in the bottle. Wine can also be carbonated through the injection of CO2, although this is not generally allowed by most food labeling legislation. To facilitate the second fermentation, wine makers introduce a small amount of sugar and yeast to the cuvée. Additional sugar may be introduced following the second fermentation to sweeten the wine. Grapes, the main ingredient of traditional sparkling wines, are C3 plants while exogenous sugar can come from either C3 (e.g., grape must, beet sugar) or C4 (e.g., corn syrup, cane sugar) sources. In many countries, the addition of sugar is only allowed to facilitate second fermentation; no large-scale introduction of sugar is allowed to sweeten the final wine product.

Martinelli et al. (2003) investigated the production of sparkling wine in Australia, South America, and the U.S through analysis of both evaporated wine residues and CO2. The δ13C values of residues suggested some wines reflected a contribution from C4 plants of 50% or more. In three samples of sparkling wine sourced from Brazil, the δ13C value of carbonation suggested the wines had been carbonated using CO2 from an exogenous source (Martinelli et al. 2003). Unlike beer, price was not a reliable indicator of the authenticity of a sparkling wine’s label.

Fraud through mislabeling is a serious issue in the wine industry. Isotope analysis—along with other chemical analysis techniques—has been used for decades in the authentication of European wines (Christoph et al. 2015). In 2007, researchers in the U.S. investigated the use of wine water δ18O values to reconstruct the climate under which grapes were grown, to help verify label claims of year and location of production (West et al. 2007). At present, however, there is no widespread application of isotope analysis to authenticate wines produced in the Americas.

Dendroprovenancing.

The field of “dendroprovenancing,” or tree sourcing, has used isotopic compositions to infer the source of wood products in archaeological settings (Bridge 2012). As a forensic case example, a study on endangered South African cycads used isotope ratio measurements of N, O, and S, plus Sr, to identify plants moved from the wild (Retief et al. 2014). Because cycad stems continuously grow, analysis of different portions of the plant inferred a change in location by a change in isotopic compositions; this suggests that plants that appear to have been in one location for a period of time (e.g., growing in a nursery) would still retain information about their original location. The timing of a move could be corroborated using 14C analysis (Retief et al. 2014), discussed in more detail in a following section.

ANIMAL ISOTOPE RATIOS AS FORENSIC EVIDENCE

Just as plants record environmental information in their tissues, so too do animals. Recording mechanisms increase in complexity from plants to animals as more inputs, outputs, and transfers must be considered, but models can be developed to relate the isotopic compositions of tissues to features of an animal’s history: what it ate, what it drank, and where it potentially lived.

Carbon, Nitrogen, and Sulfur.

C, N, and S stable isotope ratios of proteins, such as keratin of hair and nails, or collagen in bone, reflect the isotopic composition of food consumed by an individual (Klepinger 1984; DeNiro 1987). At the individual level, changes in tissue isotopic composition can be related to certain physiological conditions – e.g., hair keratin of individuals suffering eating disorders (Hatch et al. 2006). Trophic level of an organism can also influence these isotopic ratios. The term “trophic shift” is sometimes used to describe differences between the isotopic compositions of diet and consumer tissue.

On average, there is little or no shift observed between diet and “bulk” tissue δ13C values (Post 2002). However, the different sources of C atoms in the diet—protein, carbohydrate, or lipid—can have a significant effect on the δ13C values of different tissues of the consumer. For example, consumer protein, such as bone collagen, generally reflects the protein component of diet while bioapatite (a group of carbonate and phosphate minerals) generally reflects whole diet.

A positive trophic shift typically occurs for N, with consequently higher δ15N values typically observed for animals occupying higher trophic levels (Post 2002). The quality and quantity of protein in the diet can also affect animal tissue δ15N values (Robbins et al. 2005, 2010). No trophic shift has been associated with S stable isotope ratios, as they are generally conserved from diet to consumer (Nehlich 2015).

Hydrogen and Oxygen.

H and O stable isotopes in animal tissues are derived from drinking water, as well as food and water contained within the food; O is additionally derived from respiration of atmospheric O2, an isotopically homogenous source with an average δ18O value of ca. +23.5‰ (Kroopnick and Craig 1972). A common point of H and O isotopic variation in animal tissues is the body water pool (O’Grady et al. 2012; Podlesak et al. 2012). The isotopic compositions of the body water pool may be shifted from drinking water due to the addition of metabolically-derived water, as demonstrated by measuring intracellular water of both unicellular organisms (Kreuzer-Martin et al. 2005b, 2006) and higher order animals (Kreuzer et al. 2012). Thus, while animal tissues do reflect drinking water sources, sometimes that signal can be altered—through the body water pool—depending on physiological stress and should be considered when making interpretations of tissue isotopic compositions for source inference.

Because the H and O atoms in food and water consumed by an animal are largely derived from local water sources, the geographic patterns of stable isotope ratios observed in meteoric water (i.e., Figure 1) are generally reflected in the isotopic composition of animal tissues – e.g., in bones and teeth (Ehleringer et al. 2010; Meier-Augenstein 2010), as well as hair (Ehleringer et al. 2008a). These geographic patterns in the isotopic compositions of animal tissues have been successfully exploited to investigate movements of human populations in both historic and modern settings [e.g., (Thompson et al. 2014; Ehleringer et al. 2015)]. This is the case despite the potential complication (averaging effect) of relatively consistent “supermarket” diets consumed by modern humans living in different locations (Nardoto et al. 2006).

Fractionation.

Isotopic fractionation between tissue and input (i.e., food, water) may vary for each tissue type – for instance, N isotopes in hair and nail keratin may have a different trophic shift from those in bone collagen; carbonate O isotopes in bio-apatite may have a different offset from drinking water than phosphate O isotopes. The most appropriate values to assign to these apparent fractionation effects are a matter of active research, with no consensuses at present [see, for instance, (Passey et al. 2005, 2007; Daux et al. 2008; Chenery et al. 2012; Hülsemann et al. 2015)]. A forensic practitioner interpreting isotope data to reconstruct an animal’s history should provide information on the fractionation factor(s) used for interpretation of specific tissue isotope ratios. Also, as mentioned previously for plant tissues, but repeated here, the analysis of proteinaceous tissues containing labile H-atoms, such as hair, requires careful sample treatment and handling so that the measured δ2H values represent only the non-exchangeable, or intrinsic, signal and not that of ambient atmosphere in the location of analysis (Bowen et al. 2005; Chesson et al. 2009; Carter and Chesson 2017a).

FORENSIC APPLICATION OF ANIMAL ISOTOPE COMPOSITIONS

We next discuss the application of isotope analysis to animal tissues for forensic purposes – with one bacterial example for good measure.

Amerithrax Case.

In fall of 2001, a series of letters containing spores of Bacillus anthracis, the microorganism responsible for anthrax infections, were mailed to the offices of several news media outlets and two U.S. Senators. The attack became known as the “Amerithrax” case by the FBI. The 2001 anthrax attack infected 22 individuals, five of whom died as a result of infection.

All letters mailed in the attack contained spores of the same bacterial strain: the Ames strain, which was first researched at the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. At the time of the 2001 anthrax attack, the Ames strain was found at 15 biological research facilities within the U.S.—including USAMRIID and Dugway Proving Ground, in Utah—as well as three facilities located outside the U.S. As noted in the Review of the Scientific Approaches Used During the FBI’s Investigation of the 2001 Anthrax Letters,

“identification of the strain of B. anthracis used in the mailings was insufficient to identify its source, although it narrowed the possibilities considerably. The evidence had to be examined for additional unique and distinguishing features that could then be compared to samples obtained from laboratories holding the Ames strain as a means to narrow the search for the possible source material, and perpetrator(s).” (National Research Council (U.S.) 2011)

Here, forensic investigators attempted to use the isotopic compositions of the spores to provide intelligence on their growth, potentially narrowing the search. Studies on nonpathogenic B. subtilis demonstrated that the δ2H and δ18O values of bacterial spores reflect the isotopic composition of water available in the growth medium. There was a strong positive correlation between the δ2H and δ18O values of spores and those of water used to mix the liquid growth media (Kreuzer-Martin et al. 2003). When spores were grown using solid (agar) media, δ2H and δ18O values reflected both water and isotopic fractionation associated with evaporation of water from the agar during spore growth (Kreuzer-Martin et al. 2005a). Nutrients available in growth media also had an effect on δ2H and δ18O values, as well as δ13C and δ15N values (Kreuzer-Martin et al. 2004a, b).

As part of the FBI investigation of the 2001 anthrax attack, water samples were collected from Fort Detrick, Maryland, and Dugway Proving Ground, Utah. Based on published models relating water δ2H and δ18O values to spore δ2H and δ18O values (Kreuzer-Martin et al. 2003), it was deemed “highly unlikely” that water from Dugway Proving Ground was used in the growth of the spores mailed in the Amerithrax letters (National Research Council (U.S.) 2011). The Amerithrax case is currently closed, following the death by suicide of a key suspect who had worked at USAMRIID in Fort Detrick.

Food: Beef and Honey.

Food forensics is a science that seeks to determine the origins of (typically premium) food products using techniques, such as isotope analysis, that are more commonly applied in criminal forensics. The δ13C values of McDonald’s Big Mac® hamburger (beef) patties collected globally by Martinelli et al. (2011) showed that cattle diet varied with country. Hamburgers purchased in countries with an agricultural history of raising cattle on C4 grasslands or corn-based feed (e.g., Brazil, Mexico, USA) had higher δ13C values than those purchased in countries where little C4-plant material was available as cattle feed (e.g., the EU). This phenomenon was described as food “glocalization” whereby a food item available worldwide that appears physically and chemically identical is, in truth, reflecting local food production practices as differentiated by isotope analysis (Martinelli et al. 2011). Additional sourcing information could be provided by beef δ18O values, which reflect animal drinking water (Chesson et al. 2011b). In a case study of hamburgers purchased at a local restaurant and a fast food chain in Salt Lake City, Utah, the inference of beef source based on δ18O values demonstrated that beef served by the local restaurant was more likely to be raised locally to Utah than the beef served by the fast food chain (Ehleringer et al. 2015; Vander Zanden and Chesson 2017).

Research on honey has shown the promise, as well as the potential limitations, of isotope analysis of food for source inference. The δ2H values of n-alkanes of beeswax reflect local water (δ2H values (Tipple et al. 2012; Chesson et al. 2014); in contrast, the δ2H values of pollen contained within honey were only weakly correlated with local water δ2H values (Chesson et al. 2013). The δ2H values of liquid honey were not useful for sourcing due to uncontrollable water absorption and H-atom exchange in the lab prior to sample analysis (Chesson et al. 2011a). Recent results from Sr isotope analysis of liquid honey suggest 87Sr/86Sr ratios may be an additional useful marker for source inference (Chesson et al. 2017); an expanded discussion of Sr isotope signatures follows.

Human Remains.

There are two goals of isotope analysis for investigation of human remains in “cold cases”: (1) determination of whether the unidentified decedent was a resident of the region in which the remains were found; and (2) determination of likely regions from which the unknown decedent could have been at different points in time. The isotope analysis of human remains—such as hair, nail, bone, or teeth—allows an investigator to recover the isotopic signatures derived from a person’s inputs (diet and drinking water), thus providing potential source information about the individual in the “snapshots” of time represented by the tissue(s). Hair keratin records information about the weeks or months before death, depending on the rate of growth and length of hair available (Thompson et al. 2014). As bone is replaced at a rate of ~10% per year, isotope ratios of bone collagen and bio-apatite provide insight into the individual’s inputs in the decade or so before death, while tooth enamel records information about adolescence or young adulthood, depending on the tooth. Prior to analysis, tissues must be evaluated for the effects of diagenesis – the chemical and physical changes that occur due to environmental exposure and time. The selection of tissue for isotope analysis must also account for differing rates of element incorporation and replacement.

In the late 1980s, case studies on the application of isotope analysis to identify decedents began to be published (Katzenberg and Krouse 1989). Applications continue to present [see, for instance, (Meier-Augenstein and Fraser 2008; Chesson et al. 2014; Kamenov et al. 2014; Kealy et al. 2014; Font et al. 2015; Lehn et al. 2015)]. However, we note interpretation of the isotopic compositions of human tissues in modern forensic casework would not be possible without decades of pioneering work by archaeologists and anthropologists [see, for instance, other reviews (Schwarcz and Schoeninger 1991, 2012; Ambrose and Krigbaum 2003; Katzenberg 2008; Schwarcz et al. 2010)].

When dietary preference varies with geography, tissue isotopic compositions can potentially provide useful source information. For example, researchers in Brazil have used δ13C and δ15N values of fingernails to investigate dietary transitions as the economics of rural areas and urban centers change (Nardoto et al. 2006, 2011; Gragnani et al. 2014). At the global scale, the preponderance of C4 plants in “Western” diets, either through added sweeteners or animal feed, results in typically higher δ13C values of hair from North Americans relative to Europeans and Asians (Thompson et al. 2010, 2014; Valenzuela et al. 2012; Hülsemann et al. 2015). Similarly, the δ13C values of bone collagen are typically higher for residents of the USA relative to residents of Northeast and Southeast Asia; this difference can be used to screen casualties of war to determine the likely origin of unidentified decedents (Holland et al. 2012; Bartelink et al. 2014). Differences in δ34S values of hair from modern U.S. and Asia residents were also observed (Thompson et al. 2010; Valenzuela et al. 2012), with small-scale variations in δ34S values of Americans based on regional differences in dietary preference (Valenzuela et al. 2011).

Analysis of H and/or O isotope signatures in the tissues of unidentified decedents can be used to infer drinking water isotopic composition, and thus potential origin. Hair is commonly used for H and O stable isotope analysis since measurement of sequential segments provides an incremental record of an individual’s drinking water inputs in the weeks, months, or even years prior to death. Multiple studies have investigated the isotopic relationship between human hair and drinking water (Sharp et al. 2003; O’Brien and Wooller 2007; Ehleringer et al. 2008a; Bowen et al. 2009; Thompson et al. 2010), developing models to infer the δ-values of hair from those of drinking water (and vice versa) for populations consuming “supermarket diets” (Ehleringer et al. 2008a) and those consuming foods grown locally (Bowen et al. 2009; Thompson et al. 2010). Refinements of these models have accounted for temporal variability in drinking water δ18O values (Kennedy et al. 2011) and for variability in hair growth rate/stage (Remien et al. 2014).

Next we review the case of “Saltair Sally,” where human remains were found in a shallow grave west of Salt Lake City, Utah in 2000 (Ehleringer et al. 2010; Remien et al. 2014). Dental records, a facial reconstruction, and a description of personal effects found with the remains yielded no positive leads. In 2008, the medical examiner submitted some of Saltair Sally’s hair for isotope analysis. Interpretation of 18O variations in the hair suggested that in the two years prior to death, Saltair Sally traveled between four geographic regions in a cyclic fashion, staying 4-6 months in a location before moving (Ehleringer et al. 2010; Remien et al. 2014). One region included the Salt Lake City area, near where the remains were found, while another included the Pacific Northwest. After focusing investigative efforts in the states of Oregon and Washington, police matched a missing person’s report filed in 2003 to the remains, confirming identity through DNA analysis. Now known to be Nicole Bakoles, the decedent visited her mother in Seattle, Washington 12 months prior to death before returning to Utah.

Illegal Wildlife Trade.

Arguably the most common wildlife crime involves the illegal harvest of animals or plants for trade. As explained previously, the isotopic information on dietary and drinking water inputs found in animal tissues—such as bear claws, fox furs, or elephant tusks—have provided clues about the animal’s origin. This was first demonstrated in 1990 for elephant ivory and bone (van der Merwe et al. 1990; Vogel et al. 1990). Using a combination of C, N, Sr, and lead (Pb) isotope ratios, the groups showed that ivory from different populations of African elephants was distinguishable based on isotopic composition. Applying this principle, Cerling et al. showed that the C and O isotope signatures of two separate shipments of ivory carvings confiscated in Kenya likely originated from central Africa (Cerling et al. 2007; Chesson et al. 2014). Additional studies have used a combination of multiple isotope signatures (e.g., C, N, O, S, and Sr) of elephant ivory from museum collections to infer original source (Coutu et al. 2016; Ziegler et al. 2016).

Some tissues, such as hair, scute (bony external plates on turtle shell), or tail tips, can be collected without harm to an animal, making them good targets for isotope analysis to reconstruct movement history. Studies of African elephants used C and N stable isotopes of hair keratin to investigate seasonal migration patterns while populations exploit different food resources (Cerling et al. 2004, 2006, 2009), including com crops raided by elephants (Cerling et al. 2006). A recent study of horse hair combined the O isotopic composition with that of 87Sr/86Sr ratios to reconstruct the movement of a horse from South America to North America (Chau et al. 2017); see following section for more details on Sr isotopes. Isotope analysis has been used to infer whether crocodile lizards [Shinisaurus crocodilurus (van Schingen et al. 2016)] and tortoises [genus Testudo (Wood 2012)] traded as pets were captive-bred or wild-caught.

ADDITIONAL EVIDENCE FROM ISOTOPES

Compound-Specific Isotope Analysis.

As the name suggests, compound-specific isotope analysis measures the isotopic compositions of individual compounds contained within a complex matrix – e.g., individual alkanes extracted from honey (Tipple et al. 2012) or cannabis plants (Tipple et al. 2016). The analysis technique is not yet in widespread use, perhaps due to increased sample preparation effort and instrumentation required for analysis [e.g., GC-IRMS or LC-IRMS (Muccio and Jackson 2009)]. However, in an examination of human remains, researchers from the West Virginia University have shown that C stable isotope analysis of individual amino acids of hair keratin may provide further classification of samples into categories based on biometrics: sex, age, body mass index, and even health status (e.g., diabetic individuals) (Jackson et al. 2014; Rashaid et al. 2015b, a).

Strontium Isotope Analysis.

As discussed previously, the O stable isotope signatures of animal tissues, such as hair and teeth, can be used to assign probable origin by inferring drinking water δ18O values, which vary spatially. Inferences will be characteristic of a range of locations that have isotopically similar drinking water but serve to constrain the realm of all possible sources for an individual. A multi-isotope approach—e.g., through the addition of Sr isotope analysis—can help to further constrain the range of possible origins for an unidentified decedent because drinking water 87Sr/86Sr ratios also vary spatially but are not correlated with atmospheric conditions, as described below.

The 87Sr/86Sr ratio of bedrock, soil, and subsequently, drinking water, varies in the environment. The radiogenic isotope 87Sr is the product of decay of the long-lived radioisotope 87Rb. Crystalline bedrock that is old and/or rich in rubidium (e.g., old granite) has higher 87Sr/86Sr ratios, while bedrock that is young and/or rubidium poor (e.g., young basalt) has lower 87Sr/86Sr ratios (Coelho et al. 2017). In turn, the 87Sr/86Sr ratio of soils depend on many factors, including underlying bedrock, mineralogy, and other Sr sources (e.g., wind-deposited dusts, differing water supplies, etc.).

Sr in soil is substituted for calcium in plants and animals. There is no isotopic fractionation of Sr during uptake by plant roots (Flockhart et al. 2015) and the Sr isotope signal is conserved through trophic levels (Coelho et al. 2017). There are distinct geographic patterns in the Sr isotopic composition of the environment and related wildlife, but the patterns can be more complex than a direct interpretation of underlying bedrock 87Sr/86Sr ratios due to the potential contribution of other deposits.

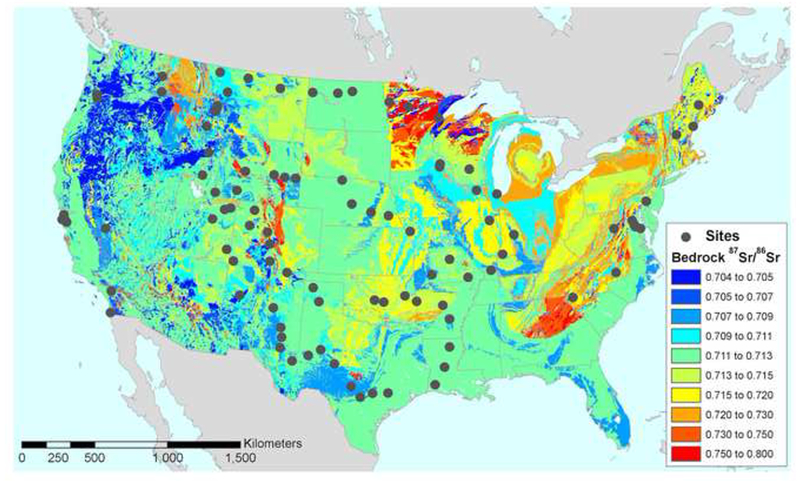

The first geographic model of the inferred Sr isotope ratios of bedrock in the USA was published almost two decades ago (Beard and Johnson 2000). More recently, Bataille and Bowen (2012) refined the bedrock Sr model to account for many of the complications related to differential bedrock weathering and water movement, generating a geographic model for Sr isotopic composition of water catchments (Bataille and Bowen 2012). Both of these models were tested using tap waters collected across the U.S. (Figure 4) and were found insufficient to infer drinking (tap) water 87Sr/86Sr ratios (Chesson et al. 2012). However, a recent compilation of Sr isotope data from analyses of surface water, soil, vegetation, and animal skeletal tissues found that the catchment model predicted 87Sr/86Sr ratios of mammalian skeletons reasonably well (Crowley et al. 2015).

Figure 4.

Sites of tap water sample collection (gray circles), displayed on an isoscape of inferred 87Sr/86Sr ratios in the coterminous USA. Isoscape from Bataille and Bowen (2012) and based on the bedrock age model of Beard and Johnson (2000). Figure from Chesson et al. (2012), reprinted under Creative Commons license. This figure is available in color in the online version of the journal.

In forensic applications, Sr isotope analysis of skeletal remains (teeth, bone) has been used to constrain potential region-of-origin of unidentified border crossers (Juarez 2008) and victims of crime (Kamenov et al. 2014; Font et al. 2015). Although Sr is not found in high concentrations in keratin, researchers have had success measuring 87Sr/86Sr ratios of hair from modern humans (Tipple et al. 2013) and horses (Chau et al. 2017). For humans, a combination of dietary Sr inputs and environmental contaminants have been related to the Sr isotope ratios of hair (Font et al. 2012; Vautour et al. 2015; Tipple et al. 2018). Recently, a semi-controlled experiment linked the 87Sr/86Sr ratios of hair to the 87Sr/86Sr ratios of tap water within a neighborhood, with small- scale variations in the 87Sr/86Sr ratios of water being recorded in hair. Here bathing water was suggested to be a significant influence on Sr isotopic composition of hair – in essence, 87Sr/86Sr ratios of hair likely reflect an individual’s most recent shower or bath (Tipple et al. 2018).

Radiocarbon Dating, or 14C Analysis.

To reconstruct the order of events, or answer questions of when, radiocarbon dating can be useful. The technique relies on measurement of a radioactive, as opposed to stable, isotope of carbon, 14C. Sometimes referred to as “age-dating,” the technique can be used to assign an age or date of tissue formation by measurement of radiocarbon content.

Radiocarbon dating is often used in forensic cases when there are questions as to the age of material. In the case of unidentified decedent Saltair Sally, discussed previously, analysis of 14C in the proximal (youngest) portion of hair suggested that she died in 1996, though her remains were not found until 2000 (Ehleringer et al. 2010). Work on human teeth has shown it may even be possible to assign year of birth to within ± 2 years if tooth identity, assigned on the Universal Number System of dental notation, is known since enamel formation takes place at particular stages of life (Alkass et al. 2011, 2013). As noted previously, the radiocarbon content of cycads was found to be useful for determining when illegally harvested plants had been relocated (Retief et al. 2014).

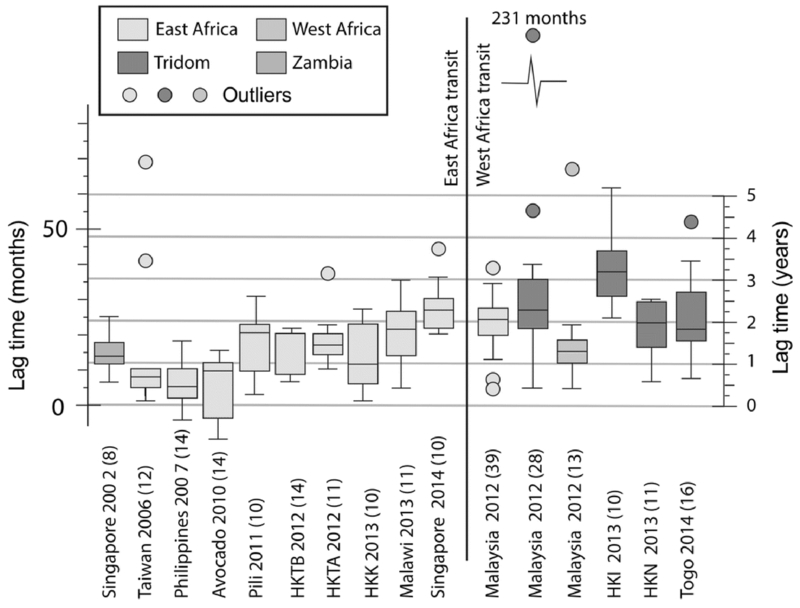

Researchers from the University of Utah have demonstrated that radiocarbon dating could be used to date elephant tusks to within a year of death (Uno et al. 2013). As many commerce regulations set by the Convention of International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) for ivory and other animal tissue are entirely predicated on age, quantitative information on when materials were sourced is required for enforcement. A survey of seized ivory assigned 14C ages and then determined the time lag between elephant death and appearance of elephant ivory on the black market (Figure 5), demonstrating that recent poaching events, and not older ivory leaking from stockpiles, was the primary source (Cerling et al. 2016b). The time lag between production to seizure calculated from the radiocarbon content of cocaine seized in the U.S. was used earlier to provide an estimate of rate of cocaine production in South America (Ehleringer et al. 2011, 2012), which may inform the effectiveness of intensive eradication efforts.

Figure 5.

Box and whisker diagram for median lag times (difference between date of death and seizure date) of confiscated ivory specimens; the number of specimens with F14C measurements for each grouping is given in parentheses. Figure reprinted with permission from Cerling et al. (2016b). Copyright (2016) National Academy of Science. This figure is available in color in the online version of the journal.

Isoscapes.

Introduced approximately a decade ago (West et al. 2006), “isoscapes,” or isotope landscapes, were a novel approach to source inference, especially in cases where there was limited reference data to make sample-to-sample comparisons of isotope signatures (Ehleringer et al. 2008b). By combining principles of isotope fractionation in materials—such as the physiological models discussed previously for plant, animal, and bacterial tissues—with the modeling capacity of geographic information systems (GIS), spatial maps of inferred isotopic compositions can be constructed (West et al. 2010a). The isotope ratio(s) measured for a sample of interest can then be compared to constructed isoscapes and inferences of potential source made.

As described earlier, spatially-dependent isotopic variations in features of the local environment, such as water δ18O values (see Figure 1), can be propagated through plants and animals. This propagation is typically accompanied by a shift of the (5-values from source into the tissue of interest. Once the relationship between source and tissue is known, it’s possible to create tissue-specific isoscapes (Bowen 2010; West et al. 2010a) – e.g., for plant water or cotton [see Figure 2, (West et al. 2008, 2010b)]. This isoscapes approach has been useful for investigating potential sources of: cotton used to make counterfeit currency; cocaine produced in South America and cannabis grown in North America; wine produced on the west coast of the USA; beef purchased at restaurants in Utah; human hair from unidentified decedents who may have traveled prior to death; and seized ivory from elephants poached in Africa. Combination of multiple isoscapes, from multiple isotope analyses of multiple compounds, could go a long way to reducing the number of potential sources in forensic investigations.

CONCLUSION

Here we’ve reviewed the recent history (~30 years) of forensic applications of isotope analysis in the Americas. The technique can be an important tool for generating forensic evidence and reaching conclusions about a material’s origin and history. Focusing on ecological applications in particular, isotope analysis can help advance studies in biology, geography, and Earth science by melding forensics and ecology. Applications of isotope analysis are anticipated to continue to develop and increase in the next 30 years.

Acknowledgment:

The Authors would like to dedicate this manuscript to Dr. James Ehleringer. His vision of how isotope analysis of ecological material could inform forensic science guided much of the work reported here.

This manuscript has benefited from comments by Dr. Glen Jackson (West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA), two anonymous reviewers, and Editor Russell K. Monson.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: MJL is a shareholder of IsoForensics, Inc. LAC, JDH, and MJL are members of the Forensic Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry Network (FIRMS).

This article does not present any new research with human participants or animals performed by any of the Authors; works reviewed here may have involved human participants or animals. For this type of study formal consent is not required.

This manuscript has been subjected to Agency review and has been approved for publication. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

REFERENCES

- Alkass K, Buchholz BA, Druid H, Spalding KL (2011) Analysis of 14C and 13C in teeth provides birth dating and clues to geographical origin. Forensic Science International 209:34–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkass K, Saitoh H, Buchholz BA, et al. (2013) Analysis of radiocarbon, stable isotopes and DNA in teeth to facilitate identification of unknown decedents. PLoS ONE 8:e69597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose SH, Krigbaum J (2003) Bone chemistry and bioarchaeology. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 22:191–192. doi: 10.1016/S0278-4165(03)00032-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amundson R, Austin AT, Schuur EAG, et al. (2003) Global patterns of the isotopic composition of soil and plant nitrogen. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 17. doi: 10.1029/2002GB001903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badeck F-W, Tcherkez G, Nogués S, et al. (2005) Post-photosynthetic fractionation of stable carbon isotopes between plant organs—a widespread phenomenon. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 19:1381–1391. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baertschi P (1976) Absolute 18O content of standard mean ocean water. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 31:341–344. doi: 10.1016/0012-821X(76)90115-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartelink EJ, Berg GE, Beasley MM, Chesson LA (2014) Application of stable isotope forensics for predicting region of origin of human remains from past wars and conflicts. Annals of Anthropological Practice 38:124–136. doi: 10.1111/napa.12047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bataille CP, Bowen GJ (2012) Mapping 87Sr/86Sr variations in bedrock and water for large scale provenance studies. Chemical Geology 304–305:39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2012.01.028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman AS, Kelly SD (2007) Fertilizer nitrogen isotope signatures. Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies 43:237–247. doi: 10.1080/10256010701550732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard BL, Johnson CM (2000) Strontium isotope composition of skeletal material can determine the birth place and geographic mobility of humans and animals. Journal of Forensic Sciences 45:1049–1061. doi: 10.1520/JFS14829J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth AL, Wooller MJ, Howe T, Haubenstock N (2010) Tracing geographic and temporal trafficking patterns for marijuana in Alaska using stable isotopes (C, N, O and H). Forensic Science International 202:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen GJ (2010) Isoscapes: Spatial pattern in isotopic biogeochemistry. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 38:161–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-earth-040809-152429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen GJ, Chesson L, Nielson K, et al. (2005) Treatment methods for the determination of δ2H and δ18O of hair keratin by continuous-flow isotope-ratio mass spectrometry. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 19:2371–2378. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen GJ, Ehleringer JR, Chesson LA, et al. (2009) Dietary and physiological controls on the hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratios of hair from mid-20th century indigenous populations. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 139:494–504. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen GJ, Revenaugh J (2003) Interpolating the isotopic composition of modern meteoric precipitation. Water Resources Research 39. doi: 10.1029/2003WR002086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge M (2012) Locating the origins of wood resources: A review of dendroprovenancing. Journal of Archaeological Science 39:2828–2834. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2012.04.028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JR, Buchmann N, Phillips S, et al. (2002) Heavy and light beer: A carbon isotope approach to detect C4 carbon in beers of different origins, styles, and prices. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 50:6413–6418. doi: 10.1021/jf020594k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JF, Chesson LA (2017a) Chapter 2: Sampling, sample preparation and analysis In: Carter JF, Chesson LA (eds) Food Forensics: Stable Isotopes as a Guide to Authenticity and Origin. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp 22–45 [Google Scholar]

- Carter JF, Chesson LA (eds) (2017b) Food forensics: Stable isotopes as a guide to authenticity and origin. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- Casale J, Casale E, Collins M, et al. (2006) Stable isotope analyses of heroin seized from the merchant vessel Pong Su. Journal of Forensic Sciences 51:603–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale JF, Ehleringer JR, Morello DR, Lott MJ (2005) Isotopic fractionation of carbon and nitrogen during the illicit processing of cocaine and heroin in South America. Journal of Forensic Sciences 50:1–7. doi: 10.1520/JFS2005077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale JF, Mallette JR (2016) Illicit coca grown in Mexico: An alkaloid and isotope profile unlike coca grown in South America. Forensic Chemistry 1:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.forc.2016.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cerling TE, Barnette JE, Bowen GJ, et al. (2016a) Forensic stable isotope biogeochemistry. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 44:175–206. doi: 10.1146/annurev-earth-060115-012303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cerling TE, Barnette JE, Chesson LA, et al. (2016b) Radiocarbon dating of seized ivory confirms rapid decline in African elephant populations and provides insight into illegal trade. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113:13330–13335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614938113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerling TE, Omondi P, Macharia AN (2007) Diets of Kenyan elephants from stable isotopes and the origin of confiscated ivory in Kenya. African Journal of Ecology 45:614–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2028.2007.00784.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cerling TE, Passey BH, Ayliffe LK, et al. (2004) Orphans’ tales: Seasonal dietary changes in elephants from Tsavo National Park, Kenya. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 206:367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.01.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cerling TE, Wittemyer G, Ehleringer JR, et al. (2009) History of Animals using Isotope Records (HAIR): A 6-year dietary history of one family of African elephants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106:8093–8100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902192106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerling TE, Wittemyer G, Rasmussen HB, et al. (2006) Stable isotopes in elephant hair document migration patterns and diet changes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103:371–373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509606102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak LA, Barbour MM, Arndt SK, et al. (2016) Stable isotopes in leaf water of terrestrial plants: Stable isotopes in leaf water. Plant, Cell & Environment 39:1087–1102. doi: 10.1111/pce.12703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau TH, Tipple BJ, Hu L, et al. (2017) Reconstruction of travel history using coupled δ18O and 87Sr/86Sr measurements of hair. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 31:583–589. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenery CA, Pashley V, Lamb AL, et al. (2012) The oxygen isotope relationship between the phosphate and structural carbonate fractions of human bioapatite. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 26:309–319. doi: 10.1002/rcm.5331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesson LA, Podlesak DW, Cerling TE, Ehleringer JR (2009) Evaluating uncertainty in the calculation of non-exchangeable hydrogen fractions within organic materials. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 23:1275–1280. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesson LA, Tipple BJ, Chakraborty S, et al. (2017) Chapter 13: Odds and ends, or, All that’s left to print In: Carter JF, Chesson LA (eds) Food Forensics: Stable Isotopes as a Guide to Authenticity and Origin. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp 303–331 [Google Scholar]

- Chesson LA, Tipple BJ, Erkkila BR, et al. (2011a) B-HIVE: Beeswax hydrogen isotopes as validation of environment. Part I: Bulk honey and honeycomb stable isotope analysis. Food Chemistry 125:576–581. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.09.050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chesson LA, Tipple BJ, Erkkila BR, Ehleringer JR (2013) Hydrogen and oxygen stable isotope analysis of pollen collected from honey. Grana 52:305–315. doi: 10.1080/00173134.2013.841751 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chesson LA, Tipple BJ, Howa JD, et al. (2014) Stable Isotopes in Forensics Applications In: Cerling TE (ed) Treatise on Geochemistry (vol 14): Archaeology & Anthropology, 2nd edn Elsevier, pp 285–317 [Google Scholar]

- Chesson LA, Tipple BJ, Mackey GN, et al. (2012) Strontium isotopes in tap water from the coterminous USA. Ecosphere 3:art67. doi: 10.1890/ES12-00122.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chesson LA, Valenzuela LO, Bowen GJ, et al. (2011b) Consistent predictable patterns in the hydrogen and oxygen stable isotope ratios of animal proteins consumed by modern humans in the USA. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 25:3713–3722. doi: 10.1002/rcm.5283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoph N, Hermann A, Wachter H (2015) 25 Years authentication of wine with stable isotope analysis in the European Union – Review and outlook. BIO Web of Conferences 5:02020. doi: 10.1051/bioconf/20150502020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho I, Castanheira I, Bordado JM, et al. (2017) Recent developments and trends in the application of strontium and its isotopes in biological related fields. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 90:45–61. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2017.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coutu AN, Lee-Thorp J, Collins MJ, Lane PJ (2016) Mapping the elephants of the 19th century East African ivory trade with a multi-isotope approach. PLoS ONE 11:e0163606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig H (1957) Isotopic standards for carbon and oxygen and correction factors for mass-spectrometric analysis of carbon dioxide. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 12:133–149. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(57)90024-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craine JM, Brookshire ENJ, Cramer MD, et al. (2015) Ecological interpretations of nitrogen isotope ratios of terrestrial plants and soils. Plant and Soil 396:1–26. doi: 10.1007/s11104-015-2542-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley BE, Miller JH, Bataille CP (2015) Strontium isotopes (87Sr/86Sr) in terrestrial ecological and palaeoecological research: Empirical efforts and recent advances in continental-scale models. Biological Reviews. doi: 10.1111/brv.12217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daux V, Lécuyer C, Héran M-A, et al. (2008) Oxygen isotope fractionation between human phosphate and water revisited. Journal of Human Evolution 55:1138–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNiro MJ (1987) Stable Isotopy and Archaeology. American Scientist 75:182–191 [Google Scholar]

- Ding T, Valkiers S, Kipphardt H, et al. (2001) Calibrated sulfur isotope abundance ratios of three IAEA sulfur isotope reference materials and V-CDT with a reassessment of the atomic weight of sulfur. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 65:2433–2437. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(01)00611-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doner LW, White JW (1977) Carbon-13/carbon-12 ratio is relatively uniform among honeys. Science 197:891–892. doi: 10.1126/science.197.4306.891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR, Bowen GJ, Chesson LA, et al. (2008a) Hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratios in human hair are related to geography. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105:2788–2793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712228105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR, Casale JF, Barnette JE, et al. (2011) 14C calibration curves for modern plant material from tropical regions of South America. Radiocarbon 53:585–594 [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR, Casale JF, Barnette JE, et al. (2012) 14C analyses quantify time lag between coca leaf harvest and street-level seizure of cocaine. Forensic Science International 214:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR, Casale JF, Lott MJ, Ford VL (2000) Tracing the geographical origin of cocaine. Nature 408:311–312. doi: 10.1038/35042680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR, Cerling TE, West JB, et al. (2008b) Spatial considerations of stable isotope analyses in environmental forensics In: Hester RE, Harrison RM (eds) Issues in Environmental Science and Technology. Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, pp 36–53 [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR, Chesson LA, Valenzuela LO, et al. (2015) Stable isotopes trace the truth: From adulterated foods to crime scenes. Elements 11:259–264. doi: DOI: 10.2113/gselements.11.4.259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR, Cooper DA, Lott MJ, Cook CS (1999) Geo-location of heroin and cocaine by stable isotope ratios. Forensic Science International 106:27–35. doi: 10.1016/S0379-0738(99)00139-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR, Dawson TE (1992) Water uptake by plants: Perspectives from stable isotope composition. Plant, Cell and Environment 15:1073–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1992.tb01657.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR, Thompson AH, Podlesak DW, et al. (2010) A framework for the incorporation of isotopes and isoscapes in geospatial forensic investigations In: West JB, Bowen GJ, Dawson TE, Tu KP (eds) Isoscapes: Understanding movement, pattern, and process on Earth through isotope mapping. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, pp 357–387 [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth PZ, Williams DG (2007) Hydrogen isotope fractionation during water uptake by woody xerophytes. Plant and Soil 291:93–107. doi: 10.1007/s11104-006-9177-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RD (2001) Physiological mechanisms influencing plant nitrogen isotope composition. Trends in Plant Science 6:121–126. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)01889-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Ehleringer JR, Hubick KT (1989) Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 40:503–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.40.060189.002443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flockhart DTT, Kyser TK, Chipley D, et al. (2015) Experimental evidence shows no fractionation of strontium isotopes (87Sr/86Sr) among soil, plants, and herbivores: Implications for tracking wildlife and forensic science. Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies 1–10. doi: 10.1080/10256016.2015.1021345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font L, van der Peijl G, van Leuwen C, et al. (2015) Identification of the geographical place of origin of an unidentified individual by multi-isotope analysis. Science & Justice 55:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2014.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font L, van der Peijl G, van Wetten I, et al. (2012) Strontium and lead isotope ratios in human hair: investigating a potential tool for determining recent human geographical movements. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry 27:719. doi: 10.1039/c2ja10361c [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gat JR (1996) Oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in the hydrological cycle. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 24:225–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.earth.24.1.225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile N, Siegwolf RTW, Esseiva P, et al. (2015) Isotope ratio mass spectrometry as a tool for source inference in forensic science: A critical review. Forensic Science International. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonfiantini R, Stichler W, Rozanski K (1995) Standards and intercomparison materials distributed by the International Atomic Energy Agency for stable isotope measurements. In: Reference and intercomparison materials for stable isotopes of light elements. Proceedings of a consultants meeting held in Vienna, 1-3 December 1993 International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Austria, pp 13–29 [Google Scholar]

- Gragnani JG, Garavello MEPE, Silva RJ, et al. (2014) Can stable isotope analysis reveal dietary differences among groups with distinct income levels in the city of Piracicaba (southeast region, Brazil)? Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 27:270–279. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann R, Nief G, Roth E (1970) Absolute isotopic scale for deuterium analysis of natural waters. Absolute D/H ratio for SMOW. Tellus 22:712–715. doi: 10.3402/tellusa.v22i6.10278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch KA, Crawford MA, Kunz AW, et al. (2006) An objective means of diagnosing anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa using 15N/14N and 13C/12C ratios in hair. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 20:3367–3373. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland TD, Berg GE, Regan LA (2012) Identification of a United States airman using stable isotopes. Proceedings of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences 18:420–421 [Google Scholar]

- Hülsemann F, Lehn C, Schneider S, et al. (2015) Global spatial distributions of nitrogen and carbon stable isotope ratios of modern human hair. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 29:2111–2121. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley JM, West JB, Ehleringer JR (2010a) Stable isotope models to predict geographic origin and cultivation conditions of marijuana. Science & Justice 50:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley JM, West JB, Ehleringer JR (2010b) Tracing retail cannabis in the United States: Geographic origin and cultivation patterns. International Journal of Drug Policy 21:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman K, Rudin N (2002) The origin of evidence. Forensic Science International 126:11–16. doi: 10.1016/S0379-0738(02)00031-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson GP, An Y, Konstantynova KI, Rashaid AHB (2014) Biometrics from the carbon isotope ratio analysis of amino acids in human hair. Science & Justice. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2014.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juarez CA (2008) Strontium and geolocation, the pathway to identification for deceased undocumented Mexican border-crossers: A preliminary report. Journal of Forensic Sciences 53:46–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2007.00610.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junk G, Svec HJ (1958) The absolute abundance of the nitrogen isotopes in the atmosphere and compressed gas from various sources. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 14:234–243. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(58)90082-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamenov GD, Kimmerle EH, Curtis JH, Norris D (2014) Georeferencing a cold case victim with lead, strontium, carbon, and oxygen isotopes. Annals of Anthropological Practice 38:137–154. doi: 10.1111/napa.12048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katzenberg MA (2008) Stable isotope analysis: A tool for studying past diet, demography, and life history In: Katzenberg MA, Saunders SR (eds) Biological Anthropology of the Human Skeleton. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, USA, pp 411–441 [Google Scholar]

- Katzenberg MA, Krouse HR (1989) Application of stable isotope variation in human tissues to problems in identification. Canadian Society of Forensic Science Journal 22:7–19. doi: 10.1080/00085030.1989.10757414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kealy G, Gapert R, Buckley L, et al. (2014) Multidisciplinary approach towards the identification of a human skull found 55 km off the south coast of Ireland In: Mallett X, Blythe T, Berry R (eds) Advances in Forensic Human Identification. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, Florida, USA, pp 193–210 [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy CD, Bowen GJ, Ehleringer JR (2011) Temporal variation of oxygen isotope ratios (δ18O) in drinking water: Implications for specifying location of origin with human scalp hair. Forensic Science International 208:156–166. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepinger LL (1984) Nutritional assessment from bone. Annual Review of Anthropology 13:75–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.an.13.100184.000451 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzer HW, Quaroni L, Podlesak DW, et al. (2012) Detection of metabolic fluxes of O and H atoms into intracellular water in mammalian cells. PLoS ONE 7:e39685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzer HW, West JB, Ehleringer JR (2013) Forensic applications of light-element stable isotope ratios of Ricinus communis seeds and ricin preparations. Journal of Forensic Sciences 58:S43–S51. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.12000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzer-Martin H, Chesson LA, Lott M, et al. (2004a) Stable isotope ratios as a tool in microbial forensics—Part 1. Microbial isotopic composition as a function of growth medium. Journal of Forensic Sciences 49: 954–960. doi: 10.1520/JFS2003226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzer-Martin HW, Chesson LA, Lott MJ, et al. (2004b) Stable isotope ratios as a tool in microbial forensics—Part 2. Isotopic variation among different growth media as a tool for sourcing origins of bacterial cells or spores. Journal of Forensic Sciences 49:1–7. doi: 10.1520/JFS2003227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzer-Martin HW, Chesson LA, Lott MJ, Ehleringer JR (2005a) Stable isotope ratios as a tool in microbial forensics—Part 3. Effect of culturing on agar-containing growth media. Journal of Forensic Sciences 50:1–8. doi: 10.1520/JFS2004513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzer-Martin HW, Ehle ringer JR, Hegg EL (2005b) Oxygen isotopes indicate most intracellular water in log-phase Escherichia coli is derived from metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102:17337–17341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzer-Martin HW, Lott MJ, Dorigan J, Ehleringer JR (2003) Microbe forensics: Oxygen and hydrogen stable isotope ratios in Bacillus subtilis cells and spores. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100:815–819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252747799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]