Abstract

Rectovaginal fistula (RVF) is a rare, but dreaded complication of Crohn's disease (CD) that is exceedingly difficult to manage. Treatment algorithms range from observation and medical therapy to local surgical repair and proctectomy. The multitude of surgical options and lack of consensus between experts speak to the complexity and shortcomings encountered to correct this disease process surgically. The key to successful management of these fistulae therefore rests on a multidisciplinary approach between the patient, gastroenterologists, and surgeons, with open communication about expectations and goals of care. In this article, we review the management of CD-associated RVF with an emphasis on surgical technique.

Keywords: rectovaginal fistula, Crohn's disease, surgery, rectal advancement flap, episioproctotomy

Rectovaginal fistula (RVF) is an infrequent, but devastating manifestation of Crohn's disease (CD), leading to significant morbidity and social embarrassment for affected women. It results from a significant inflammatory process in the anorectum that is severe enough to cause erosion through the vaginal wall, usually at the introitus. 1 Following obstetrical trauma, CD is the second most common cause of RVF, occurring in 10% of women with CD. 2

One-third to one-half of patients with RVF are asymptomatic or have minimal symptoms, requiring no treatment. 1 The remainder may present with passage of stool or gas from the vagina, while others will have less obvious complaints including dyspareunia, recurrent urinary tract infections, perineal pain, and persistent vaginal discharge. Workup includes physical exam and anoscopy which may or may not reveal the fistula tract, a formal exam under anesthesia, and radiologic imaging. 3 Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be the best imaging modality to evaluate perianal fistula disease, enabling the clinician to delineate fistula tracts, extensions, and associated abscesses. 4 5 A helpful adjunct to pelvic MRI may be endoluminal ultrasound (EUS), especially with the use of hydrogen peroxide. This method has been shown to reveal more obscure fistula tracts and fluid collections while also allowing evaluation of the anal sphincter, which is crucial for operative planning. 6

In addition to evaluating the perianal region, it is important to evaluate the entire gastrointestinal tract looking for areas of active disease. Sometimes guided by symptoms, further investigations would be computed tomographic (CT) scan, MRI, CT enterography, MR enterography, colonoscopy, or esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Any extraperineal disease should be addressed medically and/or surgically before definitive management of the RVF. 3

Treatment depends on severity of symptoms. Some women with minimal to no symptoms may be best served by recommending no/minimal treatment that does not emphasize fistula closure. Comparatively, patients with recurrent infections and significant disruptions to daily life may require more aggressive medical and/or surgical intervention with a goal to eliminate or drastically reduce vaginal drainage. Other considerations for surgical planning include the level of the fistula (high, low, or transsphincteric), the presence of proctitis, anal canal disease, rectal compliance, and sphincter dysfunction/defects. 3 In general, treatment begins with ensuring all sepsis has been drained. The next step is consideration of medical therapy, and eventually may progress to surgical intervention.

Medical Therapy

Historically, medical therapy to treat fistulizing CD had been unsuccessful, with the majority of patients eventually requiring surgery. However, advancements in immunotherapy and biologics have made pharmacologic treatment the first step in treating symptomatic RVF. The goal of medical therapy is twofold—first to treat underlying active disease and second to address the inflammation and ulceration that typically is associated with the internal opening of the fistula. Sometimes, a fistula at the base of an ulcer can then be surgically addressed when the ulcer is devoid of inflammation. Current medications used to treat perianal CD include antibiotics, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and biologics. 3

There are no randomized controlled trials to support the use of antibiotics in the treatment of fistulizing CD, with most evidence coming from small series. Regardless, metronidazole is frequently used, often in combination with other immunosuppressive agents. Used alone, it decreases the bacteroides content of the colon and has inherent immunosuppressive effects. It has been shown to close some perianal fistula; however, neurologic side effects limit the prolonged therapy that is usually required. 7 Patients are cautioned to stop the medication and call their care provider if they experience numbness and/or tingling in their hands and feet. Ciprofloxacin is often used in conjunction with metronidazole for its gram-negative coverage. Older studies have shown ciprofloxacin to aid in symptomatic control of perianal fistula used either alone or in combination with metronidazole. 8 More recently, an open-label study showed that ciprofloxacin combined with azathioprine could result in short-term healing of perianal fistula. 9 Overall, antibiotics are useful to induce short-term responses and to help overcome perianal sepsis (but may need to be combined with drainage if sepsis is extensive). They also serve as adjunctive therapy to immunosuppressive, biologic, and surgical treatment.

Most studies on immunosuppressive therapy for CD come from Present et al. 10 Their earliest randomized trial looked at 6 mercaptopurine (6-MP) for the treatment of CD. In this study, 31% of patients with fistulizing disease obtained complete closure of their fistula versus 6% in the placebo group. The subgroup of patients with RVF, however, were not analyzed separately. 10 In a follow-up study, they examined 34 patients with fistulizing disease. Two of six patients with RVF in this group attained complete closure; however, mean time to healing was 3.1 months. 11 Though the authors suggest 6-MP is effective and useful for the treatment of perianal fistula in CD, its drawbacks are the long time to response and the many side effects associated with the drug including leukopenia, pancreatitis, as well as hepatitis, and an association with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma also need to be taken into consideration. 12

In a subsequent study, they looked at cyclosporine and found a much faster clinical response to parenteral cyclosporine therapy, with 14 of 16 patients improving symptoms, and 7 of the 14 obtaining complete closure of their fistula in a mean time of 7.4 days. However, when these patients were transitioned to oral cyclosporine therapy, there were significant rates of relapse. Therefore, the authors suggest a possible role of parenteral cyclosporine as a bridge to other oral medications to treat fistulizing CD. 13

In 2004, Sands et al performed the first and only randomized controlled trial studying the efficacy of medical therapy specifically for fistulizing CD. They found that 36% of patients obtained fistula closure when using infliximab compared with 19% in the placebo group. 14 A subsequent post hoc analysis was performed to determine the efficacy and safety of infliximab specifically for RVF—the ACCENT II trial. They looked at patients who initially responded to infliximab induction therapy, and randomized them to maintenance infliximab treatment versus placebo. They found that overall 44% of patients had closure of their fistula at 54 weeks, but the duration of RVF closure was longer in the treatment group compared with placebo. 15 In a systematic review, Kaimakliotis et al found a 38.8% complete response to infliximab treatment in 67 CD-associated RVF over seven studies. 16 These trials have led most clinicians to use infliximab as first-line medical therapy for perianal fistulizing CD.

For patients who fail anti-TNF therapy, medical options are more limited. González-Lama et al performed a prospective, nonrandomized study looking at the efficacy of oral tacrolimus in patients with fistulizing CD, refractory to anti-TNF treatment. They found a 33% (one-third) complete response in patients with RVF. 17 They concluded that tacrolimus might be of benefit to those patients who fail infliximab therapy.

Overall, there have been significant improvements in medications used to treat fistulizing CD, with complete closure rates around 35 to 40% for RVF. Therefore, although pharmacologic therapy should be considered first-line treatment, the many patients may require surgical intervention.

Surgical Treatment

There are many different techniques that maybe pursued in those patients requiring surgery for CD-associated RVF. However, before definitive surgical treatment is commenced, control of perianal sepsis is paramount. As stated before, all medical or surgical treatment starts with control of perianal sepsis. This is generally accomplished with an exam under anesthesia, incision, and drainage of any perianal abscesses and placement of a seton. Proximal diversion with a stoma may be necessary to control sepsis, especially in those patients with loose, frequent bowel movements. Other areas of active CD in the small bowel could also be addressed at the time of stoma formation. A waiting period of 3 to 6 months is recommended to permit maximal clearance of inflammation and infection. 3 In addition, some authors recommend evaluation of anal wall thickness with ultrasound to ensure it has normalized before definitive repair. 12 At our institution, we typically utilize ultrasound mostly to evaluate the intactness of the anal sphincter.

Traditionally, proctectomy was the only definitive procedure to surgically address RVF, 18 as medical therapy and diversion often failed. However, evolution in surgical technique and technology has allowed for several local sphincter-sparing procedures that can be successful. Choice of procedure depends on location of the fistula, extent of proximal and distal disease, and anal sphincter integrity. Local repair can be approached transanally, transvaginally, or transperineally. 3

Simple fistulotomy for low and superficial fistulas with no sphincter involvement may be considered. This will eradicate perianal sepsis; however, patients risk development of a keyhole deformity of the anus and impaired incontinence. 3 19 As such, this procedure is rarely performed.

Most authors believe that repair of a RVF is best undertaken from the high-pressure rectal side rather than the low-pressure vaginal side. This allows optimal exposure, excision of the fistula source, and interposition of healthy tissue. 20 21 Though there are many flap configurations, the standard curvilinear rectal advancement flap (RAF) is the most commonly performed for RVF. 3

A curvilinear RAF repair should be considered in women with low fistula, a minimally diseased rectum, and a normal anal canal. It is contraindicated in patients with significant ulceration or stricturing of the anal canal, and in patients with anterior sphincter defects, 3 as these defects have been shown to impede healing and are associated with flap failure. 22 Preoperatively, all patients receive a full bowel preparation and perioperative intravenous antibiotics. A 180-degree curvilinear incision is made just distal to the fistula opening. The mucosa of the proximal anal canal is removed (mucosectomy-type approach) and a semicircular flap of mucosa, submucosa, and rectal wall is separated from the rectovaginal septum 4 to 5 cm cephalad. The fistula is excised and closed with absorbable suture (2–0 Vicryl on a UR6 needle). After ensuring enough rectal flap mobilization to prohibit tension on the flap, it is trimmed, advanced caudally, and sewn to the cut edge with absorbable sutures. The vaginal defect is left open for drainage. 3 23

RAFs for the treatment of RVF in CD have been studied since the early 1980s with varying degrees of success. The largest series of curvilinear RAF for the treatment of RVF in CD was done by Hull and Fazio. 23 In this study, 16 of 24 (67%) patients achieved complete healing, though three of these patients did need subsequent procedures. Kodner et al then reported on 24 patients treated with RAF; 71% achieved closure initially with a 92% final success rate after further repair in 5 patients. 24

The benefit of the RAF stems from its advantageous morbidity profile, with low chances of keyhole deformity formation, worsening of fecal incontinence, and exacerbation of patient symptoms in the event of flap failure. 25 These features make RAF an attractive initial option to treat CD-associated RVF.

For patients with a long high fistula, a curvilinear advancement flap is not suitable because it places excessive tension on the anastomosis. Instead, a linear advancement flap is more appropriate. The fistula tract is excised in a linear fashion, perpendicular to the dentate line. The defect is closed in layers, leaving the vaginal side open. A submucosal and mucosal flap is then mobilized which is nearly entirely in the anal canal and placed over the fistula. 23 Hull et al found a 50% healing rate in six patients treated with this type of repair.

Some surgeons prefer a transvaginal approach, where healthy vaginal tissue can be used for the flap and there is less manipulation of diseased anorectal mucosa. This technique may especially be useful in those patients who have failed a RAF or who have anal stenosis. 3 A posterior flap of vaginal tissue is raised around the fistula, identifying the rectal and vaginal openings. These are debrided and repaired with absorbable suture. The levator ani muscle is reapproximated in the midline and the vaginal flap is advanced over the repair and anastomosed to the perineal skin. 3 Sher et al reported on this technique and found complete fistula eradication in 13 of 14 patients during a mean follow-up of 55 months. Of note, all patients were diverted preoperatively or during the creation of the vaginal advancement flap. 26

Without randomized controlled trials or level I data, it is difficult to determine which method is superior for these advancement flaps—transrectal or transvaginal. Additionally, there are so many characteristics to consider that a personalized approach to the fistula may be more important than a randomized study. Ruffolo et al performed a systematic review, comparing these two approaches for CD. Though their conclusions were limited by a small number of studies with low clinical evidence, they found no significant difference in terms of primary fistula closure rate or risk of recurrence between RAF and VAF. 25 Therefore, the approach chosen should be carefully tailored to each patient's clinical scenario and surgeon experience.

When patients present with a concomitant anterior sphincter defect and RVF, the surgeon is strongly encouraged to repair the sphincter defect, as they have been associated with RAF failure. 22 This can be done with a RAF and anterior sphincteroplasty or an episioproctotomy as is done at our institution. In the episioproctotomy, a probe is placed through the fistula tract and unroofed, creating a defect similar to a fourth-degree obstetrical laceration. If a full cloaca is present, the junction between the anorectal and vaginal epithelium is incised. The fistula tract is debrided, and the sphincter muscles are identified laterally and mobilized enough to allow adequate overlap. The anorectal mucosa is first repaired with mattress sutures of absorbable suture (2–0 or 3–0 Vicryl), starting proximally and then proceeding toward the anal verge. Next, the sphincter muscle en mass (internal and external together) is overlapped and secured with 2–0 PDS. It is imperative to approximate the rectal mucosa first, as visualization of the mucosal edges and proximal border will be difficult once it is covered by the sphincter muscle. Typically, three to four sutures are used to complete the vest over pants type of overlap. The free edge is then secured with another row of sutures. Finally, the vaginal mucosa is then brought together with mattress sutures, verifying reapproximation of the hymenal ring. 27 Sometimes, the vaginal mucosa is left open to allow for drainage of fluid which may accumulate under a tightly closed suture line. Though most reports have small numbers, our institution has had good success with this procedure. El-Gazzaz et al reported a 71.4% healing rate after long-term follow-up in eight patients. 28

Another transperineal approach, more popular among gynecologists, is the transverse transperineal repair with levatorplasty. This technique is generally considered in patients with anal stenosis, sphincter dysfunction, proctitis, mucosal fibrotic scarring, and reduced rectal distensibility, and considered in patients with a large fistula openings. 29 In the technique described by Athanasiadis et al, a transverse perineal incision approximately 4 to 5 cm in length is made through the perineum, above the external sphincter. The anterior rectal wall is dissected from the posterior vagina around the fistula, continuing cephalad several centimeters above the fistula tract. Lateral dissection is performed to expose the puborectalis on both sides. The fistula tract is excised, debrided, and closed in two layers. The puborectal muscle is then reapproximated in the midline. 29 In their retrospective review of 20 patients, they had a 70% success rate after a mean follow-up of 7.1 years.

When there is normal rectum, but a significantly diseased or strictured anal canal, the rectal sleeve advancement flap may be considered, before resorting to proctectomy or permanent fecal diversion. In this procedure, all diseased tissue in the anal canal is removed (similar to a mucosectomy), and a 360-degree sleeve of healthy full-thickness rectum is mobilized. After addressing the internal opening as described for the RAF, the rectal cuff of tissues is advanced down and anastomosed to the neodentate line with absorbable suture. 30 31 At our institution, Marchesa et al studied 13 patients (11 with RVF, 1 rectourethral fistula, 1 anal canal ulceration) who underwent rectal sleeve advancement and found a 60% success rate in closure. All patients had previously undergone and failed RAFs and eight patients had proximal diversion. Whether or not to divert for the rectal sleeve advancement flap is controversial, but is nearly always done at our institution. It should be emphasized that patient selection is key to success for this procedure, and patients should be well informed that in the event that the rectum cannot be mobilized sufficiently to bring the rectum down without tension, an abdominal mobilization may be required.

In cases of recurrent RVF or after multiple procedures, the use of a muscle flap maybe beneficial. Muscle flaps have the benefit of a robust blood supply and provide healthy tissue in an area which may have significant scarring and fibrosis. This interposition of healthy tissue may improve success. Byron and Ostergard were the first to describe the use of a muscle transplant for the repair of radiation-induced recurrent RVF with the sartorius muscle. 32

In the most commonly used technique which was described by Lefèvre et al, 33 all patients were preoperatively or intraoperatively diverted and a full bowel preparation was administered the day before surgery. The patient is placed in dorsal lithotomy position. (Some surgeons first mobilize the muscle in the lithotomy position and then flip the patient into the prone position to dissect the rectovaginal septum. In this case, the muscle is left in the groin area and pulled through into the perineal wound from the prone position.) A transverse incision is made at the perineal body and the rectovaginal septum is separated at least 2 cm proximal to the fistula. The fistula is debrided and both defects are sutured closed. Two longitudinal incisions are made along the inner part of the thigh over the gracilis muscle. The muscle is dissected free, ligating collateral vessels while ensuring to preserve the neurovascular pedicle which is proximal. The tendon insertion is released from its tibial attachment, rotated, and brought through a subcutaneous tunnel to the perianal area between the rectum and vagina. Great care is taken to ensure the blood supply remains patent when the muscle is brought down. To further ensure a well-vascularized muscular pedicle, they recommend stopping the muscle dissection 6 to 8 cm away from the attachment in the proximal thigh to avoid vascular injury. Also utilizing an ultrasound to “listen” for a strong arterial signal is beneficial. The thigh incision is closed over suction drains. The gracilis muscle is carefully oriented and tacked down over the repaired anal fistula opening ensuring that it is flat and remains well vascularized. The excessive end is then rolled back toward the vagina. The perineal skin is loosely approximated and typically a flat nonsuction drain placed to prevent fluid from being trapped in the wound. With this technique, Lefèvre et al had an 88% complete healing rate in eight patients and an 80% healing rate in patients with CD over a median period of 28 months. 33 Fürst et al reported on gracilis transposition in 12 patients with recurrent RVF secondary to CD. All patients were diverted with a temporary ileostomy before graciloplasty and all but one were reversed. They had a 92% closure rate with a mean follow-up of 3.4 years and concluded that gracilis transposition should be strongly considered, especially in those patients with recurrence after failed operative therapy. 34 Wexner et al published on their experience and found less robust results, with only three of the nine women with CD-associated RVF successfully healing with gracilis interposition. 35

An alternative to the gracilis flap transposition is the Martius (bulbocavernosus) flap. The Martius flap is well described in the urologic literature for repair of cysto or urethrovaginal fistulas, 36 and has since been used by colorectal surgeons for complex RVF. It is a pedicled muscular graft harvested from the labia majora reliant on the perineal branch of the pudendal artery for its blood supply. 37 In this technique, perineal dissection as described previously is followed by a longitudinal incision over the labia majora. Skin flaps are raised until the entire fat pad with bulbocavernosus muscle is fully mobilized and disconnected as close to the pubic bone as possible. A subcutaneous tunnel is created to the mobilized rectovaginal septum and the anterior end of the flap is pulled through the tunnel and sutured to the posterior vaginal wall. 3 McNevin et al reported on 16 patients with complex anovaginal fistula, 2 with CD etiology. They reported one recurrence during a mean follow-up of 75 weeks. 37

If native tissue is unavailable to produce an adequate advancement flap or tissue graft, interposition with a bioprosthetic mesh has been reported in the literature, albeit in small numbers. This bioprosthesis is typically made from lyophilized porcine intestinal submucosa, with the Surgisis mesh being the product most frequently utilized in the literature.

In the technique described by Schwandner and Fuerst, a combined transvaginal and transrectal approach is performed. The fistula tract is identified from the vaginal side. The rectovaginal space is entered and the vagina is dissected away from the rectum approximately 1 cm proximal and distal to the fistula tract. The fistula tract is excised and a standard RAF is mobilized. The rectovaginal space is then irrigated with antiseptic solution and the Surgisis mesh is placed in the rectovaginal space and fixed to each corner with absorbable suture. The posterior vaginal wall is closed over the mesh. Out of nine patients with CD-associated RVF, two recurred at a median follow-up time of 16 months. 38 In another study by the same group looking only at CD-associated RVF and transsphincteric fistulas, they found a 66% closure rate in the RVF arm. 39

Bioprosthetic-augmented repair is an option to treat RVF. However, in the event of failure, there tends to be a cardboard type of reaction that may impair further attempts at repair and therefore we do not typically advocate its use at our institution.

Most recently, García-Arranz et al were the first group to publish the use of stem cells to treat CD-related RVF. In a phase I–IIa clinical trial, they used extended allogeneic adipose-derived stem cells (e-ASCs) to enhance regeneration and repair of damaged tissues. They hypothesize that the stem cell effect is due to their immunoregulatory and anti-inflammatory properties that may work in concert to accelerate healing. These stem cells are derived from subcutaneous fat, making them readily available and abundant. This group previously performed a phase I and II clinical trial investigating the use of autologous stem cells in Crohn's-related and cryptoglandular fistulas, and a phase III trial studying complex perianal fistulas. These studies proved e-ASCs to be safe and effective, 40 thus prompting an investigation into the application in RVF treatment.

In their protocol technique, they identified the vaginal and rectal openings, curetted the fistula tract, and a vaginal or RAF was created at the discretion of the surgeon. Twenty million e-ASCs were injected into the vaginal opening and fistula tract. Patients who did not achieve total reepithelialization were rescued with a second cell dose. They found that the administration of donor e-ASCs was safe based on the observed side effect profile. To evaluate for stem cell rejection, they measured cytokine levels and found no differences before and after treatment, indicating that e-ASCs were well tolerated. As part of their protocol, however, patients were excluded if they had anti-TNF administration within 8 weeks or had tacrolimus or cyclosporine within 4 weeks of e-ASC injection. As a result, 5 out of 10 patients were unable to complete the trial secondary to CD flare-ups requiring immunosuppressive or biologic therapy. Of the five remaining patients, 60% achieved complete closure of their fistula at 52 weeks. 40 Though stem cell therapy did seem to facilitate RVF closure, further studies are needed to evaluate the safety of allogeneic stem cell injection with biologic medications. If this proves to be safe, stem cell therapy may play an important role in the treatment of CD-associated RVF.

For any type of repair, the use of fecal diversion remains a controversial topic. Proximal diversion does improve symptomatology and aide in controlling pelvic sepsis and inflammation; however, results are equivocal in terms of RVF healing and closure. 2 Some authors advocate routine diversion regardless of repair type, while others are more selective. At our institution, proximal diversion is recommended for redo repairs, technically challenging repairs and suboptimal tissue conditions. 2

As mentioned earlier, traditionally proctectomy was the only acceptable surgical option for RVF. Despite the many recognized closure techniques available today, some patients have disease and conditions and do not qualify for any closure therapy. Similarly they may also have intolerable symptoms or uncontrollable sepsis. For this group of patient, proctectomy may be recommended. This particularly is true for women with pan colonic disease or extensive anorectal involvement. Though definitive, the procedure is fairly morbid and comes with its own set of complications, particularly with regard to perineal wound healing and the possibility of perineal sinus tract formation in up to 50% of patients. 3

The management of RVF in CD is daunting and challenging, leading to significant frustration for the clinician and the patient. There are no standardized protocols for treatment since level I evidence is lacking 2 and we feel that individualization is required before embarking on a treatment plan. Therefore, the treating physician must be familiar with multiple medical and surgical options. Successful treatment stems from an understanding that Crohn's is a systemic disease. Thus, a thorough assessment of the patient's symptomatology, treating extraperineal disease, and eliminating pelvic sepsis before definitive repair are essential steps to achieve fistula closure.

Given the complexity of this disease process and the significant variability in treatment outcomes, the patient should play an active role in treatment decisions and clear expectations should be emphasized by the clinician. A collaborative effort between the medical doctor (usually a gastroenterologist) and surgeon further can optimize tissue conditions and allow for consideration of a wide range of treatment options.

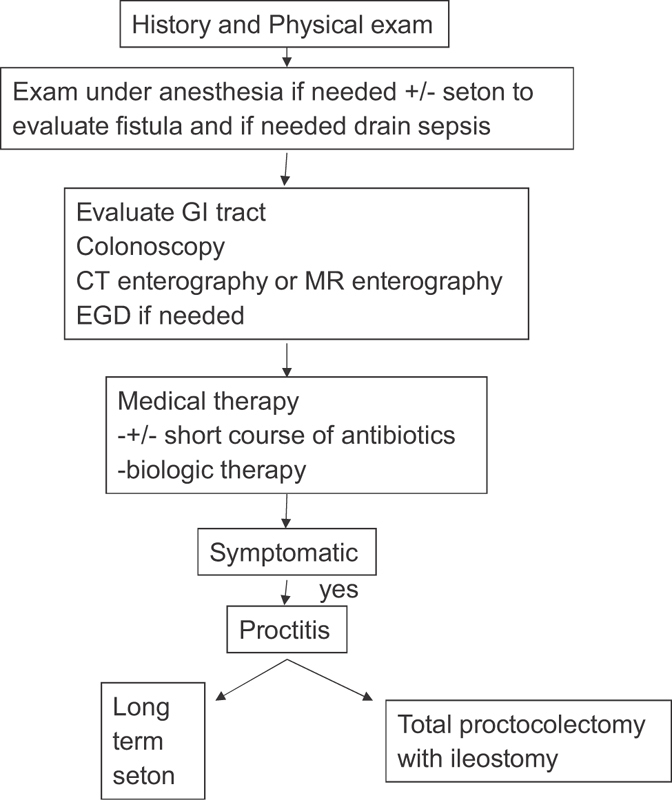

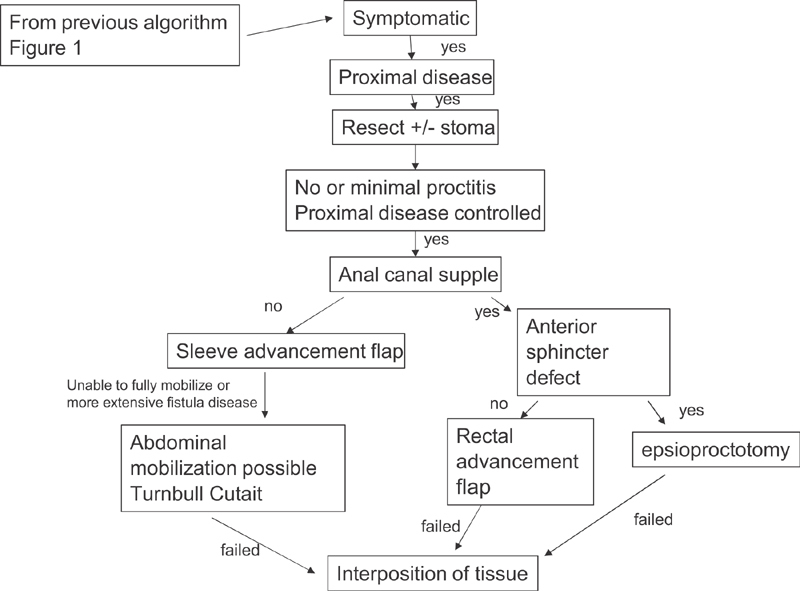

Fig. 1 gives our algorithm for treatment. Fig. 2 gives our algorithm for our approach toward surgical closure of Crohn's ano/rectovaginal fistula.

Fig. 1.

Algorithm of treatment.

Fig. 2.

Algorithm for surgical closure.

References

- 1.Fichera A, Zoccali M; Crohn's & Colitis Foundation of America, Inc.Guidelines for the surgical treatment of Crohn's perianal fistulas Inflamm Bowel Dis 20152104753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hannaway C D, Hull T L.Current considerations in the management of rectovaginal fistula from Crohn's disease Colorectal Dis 20081008747–755., discussion 755–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valente M A, Hull T L. Contemporary surgical management of rectovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014;5(04):487–495. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v5.i4.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szurowska E, Wypych J, Izycka-Swieszewska E. Perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease: MRI diagnosis and surgical planning: MRI in fistulizing perianal Crohn's disease. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32(06):705–718. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheedy S P, Bruining D H, Dozois E J, Faubion W A, Fletcher J G. MR imaging of perianal Crohn disease. Radiology. 2017;282(03):628–645. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016151491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sloots C E, Felt-Bersma R J, Poen A C, Cuesta M A, Meuwissen S G. Assessment and classification of fistula-in-ano in patients with Crohn's disease by hydrogen peroxide enhanced transanal ultrasound. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16(05):292–297. doi: 10.1007/s003840100308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandt L J, Bernstein L H, Boley S J, Frank M S. Metronidazole therapy for perineal Crohn's disease: a follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 1982;83(02):383–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenbloom S L, Steinhart A H, Greenberg G R. Combination ciprofloxacin and metronidazole for active Crohn's disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 1998;12(01):53–56. doi: 10.1155/1998/349460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dejaco C, Harrer M, Waldhoer T, Miehsler W, Vogelsang H, Reinisch W.Antibiotics and azathioprine for the treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease Aliment Pharmacol Ther 200318(11-12):1113–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Present D H, Korelitz B I, Wisch N, Glass J L, Sachar D B, Pasternack B S. Treatment of Crohn's disease with 6-mercaptopurine. A long-term, randomized, double-blind study. N Engl J Med. 1980;302(18):981–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198005013021801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korelitz B I, Present D H. Favorable effect of 6-mercaptopurine on fistulae of Crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1985;30(01):58–64. doi: 10.1007/BF01318372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreani S M, Dang H H, Grondona P, Khan A Z, Edwards D P. Rectovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(12):2215–2222. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Present D H, Lichtiger S. Efficacy of cyclosporine in treatment of fistula of Crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39(02):374–380. doi: 10.1007/BF02090211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sands B E, Anderson F H, Bernstein C N et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(09):876–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sands B E, Blank M A, Patel K, van Deventer S J; ACCENT II Study.Long-term treatment of rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn's disease: response to infliximab in the ACCENT II Study Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004210912–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaimakliotis P, Simillis C, Harbord M, Kontovounisios C, Rasheed S, Tekkis P P. A systematic review assessing medical treatment for rectovaginal and enterovesical fistulae in Crohn's disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(09):714–721. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.González-Lama Y, Abreu L, Vera M I et al. Long-term oral tacrolimus therapy in refractory to infliximab fistulizing Crohn's disease: a pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11(01):8–15. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuxen P A, Castro A F. Rectovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1979;22(01):58–62. doi: 10.1007/BF02586761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nosti P A, Stahl T J, Sokol A I. Surgical repair of rectovaginal fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;171(01):166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenwald J C, Hoexter B. Repair of rectovaginal fistulas. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;146(03):443–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen J L, Stricker J W, Schoetz D J, Jr, Coller J A, Veidenheimer M C. Rectovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32(10):825–828. doi: 10.1007/BF02554548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsang C B, Madoff R D, Wong W D et al. Anal sphincter integrity and function influences outcome in rectovaginal fistula repair. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41(09):1141–1146. doi: 10.1007/BF02239436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hull T L, Fazio V W. Surgical approaches to low anovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease. Am J Surg. 1997;173(02):95–98. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kodner I J, Mazor A, Shemesh E I, Fry R D, Fleshman J W, Birnbaum E H.Endorectal advancement flap repair of rectovaginal and other complicated anorectal fistulas Surgery 199311404682–689., discussion 689–690 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruffolo C, Scarpa M, Bassi N, Angriman I. A systematic review on advancement flaps for rectovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease: transrectal vs transvaginal approach. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(12):1183–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sher M E, Bauer J J, Gelernt I. Surgical repair of rectovaginal fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease: transvaginal approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34(08):641–648. doi: 10.1007/BF02050343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hull T L, Bartus C, Bast J, Floruta C, Lopez R. Multimedia article. Success of episioproctotomy for cloaca and rectovaginal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(01):97–101. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0790-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El-Gazzaz G, Hull T, Mignanelli E, Hammel J, Gurland B, Zutshi M. Analysis of function and predictors of failure in women undergoing repair of Crohn's related rectovaginal fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(05):824–829. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Athanasiadis S, Yazigi R, Köhler A, Helmes C. Recovery rates and functional results after repair for rectovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease: a comparison of different techniques. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22(09):1051–1060. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0294-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marchesa P, Hull T L, Fazio V W. Advancement sleeve flaps for treatment of severe perianal Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 1998;85(12):1695–1698. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cutait D E, Cutait R, Ioshimoto M, Hyppólito da Silva J, Manzione A. Abdominoperineal endoanal pull-through resection. A comparative study between immediate and delayed colorectal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28(05):294–299. doi: 10.1007/BF02560425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Byron R L, Jr, Ostergard D R. Sartorius muscle interposition for the treatment of the radiation-induced vaginal fistula. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969;104(01):104–107. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)34147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lefèvre J H, Bretagnol F, Maggiori L, Alves A, Ferron M, Panis Y. Operative results and quality of life after gracilis muscle transposition for recurrent rectovaginal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(07):1290–1295. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a74700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fürst A, Schmidbauer C, Swol-Ben J, Iesalnieks I, Schwandner O, Agha A. Gracilis transposition for repair of recurrent anovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23(04):349–353. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wexner S D, Ruiz D E, Genua J, Nogueras J J, Weiss E G, Zmora O. Gracilis muscle interposition for the treatment of rectourethral, rectovaginal, and pouch-vaginal fistulas: results in 53 patients. Ann Surg. 2008;248(01):39–43. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31817d077d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rangnekar N P, Imdad Ali N, Kaul S A, Pathak H R. Role of the martius procedure in the management of urinary-vaginal fistulas. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191(03):259–263. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNevin M S, Lee P YH, Bax T W.Martius flap: an adjunct for repair of complex, low rectovaginal fistula Am J Surg 200719305597–599., discussion 599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwandner O, Fuerst A, Kunstreich K, Scherer R. Innovative technique for the closure of rectovaginal fistula using Surgisis mesh. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13(02):135–140. doi: 10.1007/s10151-009-0470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwandner O, Fuerst A. Preliminary results on efficacy in closure of transsphincteric and rectovaginal fistulas associated with Crohn's disease using new biomaterials. Surg Innov. 2009;16(02):162–168. doi: 10.1177/1553350609338041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.García-Arranz M, Herreros M D, González-Gómez C et al. Treatment of Crohn's-related rectovaginal fistula with allogeneic expanded-adipose derived stem cells: a phase I-IIa clinical trial. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016;5(11):1441–1446. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]