Abstract

Oncogenic fusions involving NTRK1, NTRK2, and NTRK3 with various partners are diagnostic of infantile fibrosarcoma and secretory carcinoma yet also occur in lower frequencies across many types of malignancies. Recently, targeted small molecular inhibitor therapy has been shown to induce a durable response in a high percentage of patients with NTRK fusion-positive cancers, which has made the detection of NTRK fusions critical. Several techniques for NTRK fusion diagnosis exist, including pan-Trk immunohistochemistry, fluorescence in situ hybridization, reverse transcription PCR, DNA-based next-generation sequencing (NGS), and RNA-based NGS. Each of these assays has unique features, advantages, and limitations, and familiarity with these assays is critical to appropriately screen for NTRK fusions. Here, we review the details of each existing methodology.

Keywords: NTRK fusion, Immunohistochemistry, Fluorescence in situ hybridization, Next-generation Sequencing

INTRODUCTION

The neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase genes (NTRK1, NTRK2, and NTRK3) encode a family of receptor tyrosine kinases (TrkA, TrkB, and TrkC, respectively) that serve important roles in cell survival, proliferation, and cellular differentiation in healthy human cells.[1] The Trk proteins are physiologically expressed predominantly in the central and peripheral nervous system as well as smooth muscle.[2, 3] Physiologic activation of the receptors is initiated by neutrotrophin binding to the extracellular domain, causing receptor dimerization and phosphorylation, and subsequent downstream activation of signaling pathways including phospholipase C, Ras/MAPK/ERK, and PI3K cascades.[1, 4, 5]

In-frame fusions involving any of various partners in the 5’ position, several of which are detailed by Cocco et al in a recent paper,[5] and the kinase domain of one of the three NTRK genes in the 3’ position are transcribed and translated into a fusion protein, resulting in aberrant expression and ligand-independent activation, and hence continuous, unregulated increased signaling of Trk and activation of its downstream targets. While the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion was originally described in infantile fibrosarcoma[6, 7] and secretory carcinoma of the breast and salivary gland,[8–10] other fusions involving the Trk proteins have been demonstrated in a vast array of tumor types, including other sarcomas,[11] melanocytic neoplasms,[12, 13] inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors,[14] gliomas,[15, 16] and carcinomas of the lung,[17] colon,[18] and thyroid.[19–21]

These fusions were discovered approximately twenty years ago, but the very recent development of Trk inhibitors and their approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has revitalized the interest of the oncology community. Approved in 2017, entrectinib exhibits activity against Trk as well as ROS1 and ALK oncogenic fusions. More recently, in November of 2018, the FDA granted accelerated approval for Larotrectinib (Bayer and Loxo Oncology), a potent small molecule inhibitor with high selectivity for Trk.[22] Both have shown great promise in recent clinical trials. Entrectinib has shown efficacy in many tumor types exhibiting Trk fusions.[23–25] Similarly, Drilon et al. recently reported the results of a phase I histology-agnostic clinical trial of larotrectinib in adult and pediatric patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors harboring an NTRK fusion. A dramatic response rate was seen, with 75% of patients responding and 55% of patients remaining progression free at 1 year.[26] Clinical responses were seen regardless of patient age, fusion partner, NTRK gene, and tumor type.

NTRK fusions occur in over 90% of infantile fibrosarcomas and secretory carcinomas yet are exceedingly rare in more common malignancies: 0.23% of a cohort of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NCSLC),[17] 0.35% of a cohort of patients with colorectal carcinomas,[27] and 0.27% of a cohort of 11,500 patients with various solid tumors harbored NTRK fusions.[28] Given their only recently recognized therapeutic relevance, their rarity in common malignancies, and the challenge of accurately detecting the variety of NTRK fusions with different partners and genomic breakpoints, there has emerged a need in the pathology and oncology communities for detailed knowledge regarding assays for the detection of NTRK fusions. Here, we review the advantages and limitations of currently available testing modalities including immunohistochemistry (IHC), fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), DNA-based next-generation sequencing (NGS), and RNA-based NGS. These findings are summarized in Table 1. It should be noted that NTRK fusions, which are both rare and diverse, are still being investigated, and recent studies assessing the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for NTRK fusion detection assays have shown variable results. The true clinical validity and clinical utility of these assays may require years of additional study and more thorough evaluation of patient outcomes.

Table 1.

Features, advantages, and limitation of various assays used to identify NTRK fusions.

| Testing method | Sensitivity | Specificity | Material required | Turn-around time | Cost | Additional notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunohistochemistry | 75–96%. Higher for NTRK1 & NTRK2 fusions, but approximately 50–70% for NTRK3 fusions.[28–31] | 92–100%. False positives seen in tumors with neural or smooth muscle differentiation | At least 1 unstained slide. Additional may be required for controls | 1 day | $ | Interpretation should take histologic tumor type into account |

| Fluorescent in situ hybridization | High sensitivity if canonical breakpoints | High specificity | At least 3 unstained slides. (1 for each NTRK gene tested) | 1–3 days | $ | Useful when high suspicion of ETV6-NTRK3 fusions and supporting histology |

| Reverse transcription PCR | Variable. Both involved genes and exons must be known) RNA must be of sufficient quality | Variable. Dependent upon whether structural variant results in transcribed fusion | 1 F06Dg of RNA (approximately 50,000 cells). | 1 week | $ | Can be quantitative |

| DNA-based Next-Generation Sequencing | Variable. Depends on extent and depth of NTRK1–3 introns covered as well as tumor purity | Variable. Dependent upon whether structural variant results in transcribed fusion | 250 ng of DNA (approximately 50,000 cells). We cut 20 unstained slides at 5 μm for biopsies; 15 unstained slides for resections | 2–4 weeks | $ $ $ | Also assesses point mutations and potentially other fusions so that RAS/BRAF wild type tumors can be further tested if needed |

| RNA-based Next-Generation Sequencing | Very high if RNA quality is sufficient | Very high | 200 ng of RNA, (approximately 10,000 cells). We cut 10 unstained slides at 5 μm. | 2–4 weeks | $ $ $ | Assesses fusions across multiple genes |

| DNA/RNA hybrid sequencing assays | 98–100% [48, 49] | 96–100% [48, 49] | 10–40 ng of RNA at greater than 20% tumor content | 2–4 weeks | $ $ $ | Can assess fusions, splice variants, indels, point mutations, and copy number variants simultaneously |

IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY

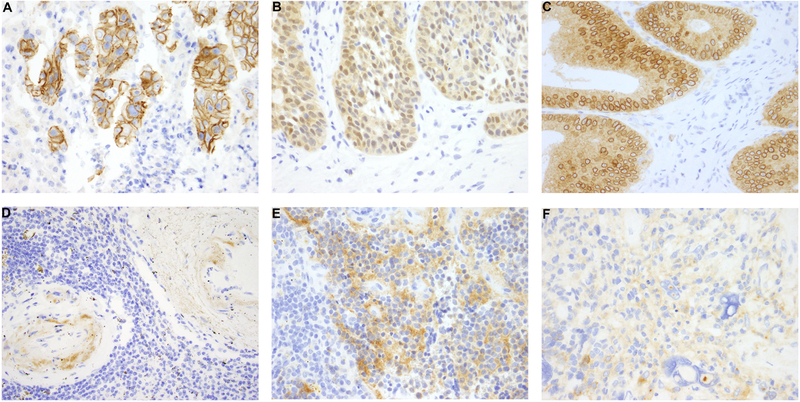

Widely available to most clinical labs, IHC has the advantages of being inexpensive, having a rapid turnaround time of approximately 1 day, requiring as little as 1 unstained slide, and working independent of tumor purity. Antibody clone EPR17341, commercially available from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) and Roche/Ventana (San Francisco, CA), is the most studied clone available and is reactive with a conserved proprietary peptide sequence from the C-terminus of TrkA, TrkB, and TrkC. The Abcam antibody has demonstrated a sensitivity for the detection of NTRK fusions ranging from 75% to 96.7% and a specificity ranging from 92 to 100%.[28–31] Cytoplasmic staining appears to be universal in NTRK fusion positive tumors, but fusion partner-specific staining patterns have also been observed (Figure 1A–C).[29] The 3 predominant patterns that have been described reflect localization of the fusion protein to the subcellular site of the fusion partner. For example, ETV6-NTRK3 fusion positive samples demonstrate nuclear Trk expression, while LMNA-NTRK1 fusion positive samples demonstrated peri-nuclear Trk expression as LMNA encodes nuclear lamin, and NTRK fusions with tropomyosin (TPM) partners show membranous staining as TPM encodes proteins that localize to the cytoskeleton.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining with pan-Trk antibody (clone EPR 17341, Abcam) demonstrates a variety of staining patterns in malignancies with NTRK fusions, and the staining patterns correlate with the fusion partner. (A) A membranous staining pattern is seen in this case of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with a PLEKHA6-NTRK1 fusion. (B) A nuclear and cytoplasmic staining pattern is seen in this case of secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland with the canonical ETV6-NTRK3 fusion. (C) Colonic adenocarcinoma with an LMNA-NTRK1 fusions exhibits a cytoplasmic and perinuclear staining pattern. (D) Physiologic staining can be seen in smooth muscle, as seen in arterial walls. (E-F) Physiologic staining can also be seen in tumors of neural differentiation, such as neuroblastoma (E) and glioblastoma (F), making interpretation difficult.

Decreased sensitivity has been observed, however, for NTRK3 fusions. In perhaps the largest study of pan-TRK IHC to date, 4138 cases, including 28 confirmed NTRK fusion-positive cancers, were examined. While sensitivity was 88% and 89% for NTRK1 and NTRK2 fusions, respectively, only 6 of 11 cases with NTRK3 fusions were positive with clone EPR17341.[28] Thus, in patients with histology suggestive of secretory carcinoma or infantile fibrosarcoma, diagnostic testing for ETV6-NTRK3 fusion with other assays (NTRK3 FISH, RNA-based NGS, or RT-PCR) is of higher clinical yield. For patients with tumor histologies highly enriched in ETV6-NTRK3 fusions, it may be sufficient to verify the presence of NTRK3 rearrangement with NTRK3 FISH.

Another limitation of pan-TRK IHC is the physiologic expression of Trk in neural as well as smooth muscle tissue (Figure 1D–F).[2, 3] IHC expression has been observed in fusion-negative tumors with neural or smooth muscle differentiation such as gastrointestinal stromal tumor, neuroblastoma, glioblastoma, leiomyosarcoma, primitive myxoid mesenchymal tumor of infancy, and fibrous hamartoma of infancy.[11, 29, 31, 32] Thus, tumors with neural and smooth muscle differentiation should not be screened via pan-Trk IHC for NTRK fusions.

FLUORESCENT IN SITU HYBRIDIZATION

FISH is a DNA-based assay performed with either fusion probes or break-apart probes and is used to assess DNA-level structural variants in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue (FFPE). One of the most commonly used commercial probes is an ETV6 break-apart probe that has shown efficacy in confirming ETV6-NTRK3 rearrangements in secretory carcinoma and infantile fibrosarcoma.[33] These break-apart probe sets often include a green-labeled probe at the 3’ end of ETV6 and an orange-labeled probe that overlaps the 5’ end of ETV6.[33] A positive result is a split or isolated 5’ signal, with thresholds varying from 5% of cells [14] to 15% of tumor cells.[34] Other laboratories have used NTRK1, NTRK2, and NTRK3 break-apart probes to identify NTRK fusions.[11, 35] While a positive FISH result with a break-apart probe means that there is a structural variant involving the tested gene, neither the functional significance (whether the DNA-level structural variant results in a translated fusion) nor the partner is known. ETV6 or NTRK3 FISH is useful to support a histologic diagnosis of secretory carcinoma or infantile fibrosarcoma.[36] In theory, FISH has good sensitivity and specificity, and is often used as the gold standard for assessing for the presence of chromosomal abnormalities. However, one caveat is that if the breakpoints involve noncanonical sites or novel genes, the test will be reported as falsely negative.[36, 37] FISH testing generally has a quick turnaround time of less than a week, only uses 1–2 slides, and works well on low tumor purity samples.

REVERSE TRANSCRIPTION POLYMERASE CHAIN REACTION

RT-PCR is an RNA-based method for assessing NTRK fusion transcripts that can be performed either as a qualitative assay or as real-time quantitative PCR. This assay requires knowledge of both fusion partners and their exon breakpoints. In many cases, the canonical ETV6 exon5-NTRK3 exon15 fusion can be detected. However, a recent study examined a cohort of 25 salivary gland secretory carcinomas that lacked the canonical fusion by conventional RT-PCR. In four cases, the canonical fusion could be detected using highly sensitive nested RT-PCR techniques, and in five cases, an atypical ETV6 exon 4-NTRK3 exon 14 fusion was detected.[35] Overall, while RT-PCR has demonstrated great clinical utility in diagnosis and monitoring of other fusion-driven malignancies such as chronic myelogenous leukemia and acute promyelocytic leukemia, the diversity of NTRK fusion partners, variability of breakpoints and exons involved, and lability of RNA in archival FFPE tissue limits this technique’s utility.

DNA-BASED NEXT-GENERATION SEQUENCING

DNA-based NGS assays examine genomic DNA from tumors to assess somatic mutational status of many genes simultaneously. These assays range from targeted assays that focus on a small or large panel of cancer-related genes, to whole exome and even whole genome sequencing. The platforms, chemistry and bioinformatic pipelines used in these assays can be highly variable. For instance, the assay used at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, MSK-IMPACT, is hybridization capture-based and covers the entire coding region of 468 cancer-related genes as well as select introns including those in ETV6, NTRK1, and NTRK2.[29, 38] Similarly, the FoundationOne CDx™ assay covers 324 cancer-related genes and can detect rearrangements involving ETV6, NTRK1, and NTRK2. The sensitivity of DNA-based assays that include such cancer gene panels as well as whole exome sequencing depends on whether the genomic breakpoints of a defined fusion are covered by the panel, and how much coverage is present at that breakpoint. For both the FoundationOne CDx™ and MSK-IMPACT assays, only the exonic regions of NTRK3 are covered, and because fusion breakpoints usually occur within introns, inadequate coverage of these introns can result in false negatives. Not only is coverage of the intronic regions impractical due to size limitations---the intronic regions, especially in the area of the exons coding for the NTRK3 kinase domain, span up to 200 kilobases in length---but the intronic regions also contain highly repetitive regions that are impossible to tile in a hybridization-capture assay. Therefore, due to these considerations, sensitivity of detection of NTRK3 fusions is limited.

One distinct advantage of DNA-based NGS testing is its ability to simultaneously assess mutations, amplifications, deletions, microsatellite instability status, and tumor mutation burden, as well as fusions.[38, 39] The knowledge of other oncogenic MAPK DNA-based alterations, such as BRAF p.V600E, RAS mutations, and other kinase fusions, is of particular value when triaging cases for follow-up NTRK fusion testing with other assays. For example, in a study of 21 colorectal carcinomas harboring kinase fusions, none had a BRAF, KRAS, NRAS mutation.[27] In contrast, however, one study demonstrated KRAS alterations co-occurring with NTRK fusions in two cases of neuroendocrine carcinoma.[40] For the most part, since NTRK fusions and alterations in BRAF/RAS appear to be mutually exclusive, it may be possible to narrow down the cohort of common tumors that require fusion screening based on BRAF/RAS status.

In terms of specificity, the detection of a structural variant involving one of the NTRK genes shares the same problem as DNA-level rearrangements detected by FISH: they may not result in an expressed in-frame fusion protein, and therefore further assessment using alternative methods is often required for more information on the NTRK event. Other considerations for DNA-based NGS assays are that they require adequate tumor purity, adequate tissue from unstained slides or FFPE tissue curls, and turnaround time is generally at least two weeks.

RNA-BASED NEXT-GENERATION SEQUENCING

RNA-based NGS involves extraction of RNA from FFPE followed by preparation of cDNA and sequencing. One study examined the use of multiplexed amplicon-based sequencing to assess for fusion transcripts involving 19 driver genes and 94 possible partners.[41] The authors demonstrated 86% sensitivity for cases with at least 10 normalized reads when comparing against other methodologies including FISH, RT-PCR, Sanger sequencing and NGS panels. Sensitivity was improved by assessing for kinase domain overexpression by identifying differences in expression of the 3’ and 5’ aspects of the potential driver genes, a finding associated with fusion protein forming translocations.[42] Including 3’/5’ read ratios and decreasing the normalized fusion read requirement resulted in 100% sensitivity.[41]

An alternative method, anchored multiplex PCR, for example with the Archer FusionPlex® platform, has a benefit over amplicon based methods: gene fusions can be detected even if only one of the fusion partners is known.[43] In this method, a gene specific primer hybridizes to the NTRK (or other kinase gene) while a “universal” primer hybridizes to an adapter sequence downstream of the fusion partner. After cleanup, a second round of amplification is performed, again using a gene specific primer 3’ downstream to the first and a second universal primer again complementary to the adapter sequence. Once the PCR steps have been performed to create the library, sequencing and analysis is performed to quantify the processed transcripts.[43–45]

The main advantages of RNA-based NGS are that evidence of transcription is positively identified and the exact genes and exons involved in the transcript are characterized. In contrast to RT-PCR methods, as described above, RNA-based NGS methods can assess for the presence of fusions involving multiple genes and exons simultaneously.

The limiting factor for RNA-based sequencing methods is RNA quality. RNA is more labile than DNA due to the presence of hydroxyl groups and subsequent hydrolysis, and it is often degraded in FFPE tissues, especially with increasing storage time and age of tissue. Although many recent advances have improved the efficiency of RNA library preparation, laboratory handling of RNA samples requires highly specialized reagents, equipment, and expertise.[46] Adequate quality control measures are therefore important to assess both the amount and quality of the RNA obtained. Metrics can include distribution of RNA fragment sizes, proportion of sequencing reads that are RNA versus DNA, and average sequencing coverage and depth.[47]

HYBRID DNA/RNA PANELS

Recently, platforms able to assess both DNA and RNA extracted from the same FFPE sample have been developed. After separate DNA and RNA library preparation, the libraries are pooled for interrogation in a single sequencing run. Covering 170 genes commonly altered in solid tumors, the TruSight Tumor 170, one such assay developed by Illumina, can assess fusions, splice variants, indels, point mutations, and copy number variants simultaneously. This assay uses hybridization capture to enrich the library for genes of interest prior to sequencing,[48] and it can thereby capture transcribed fusions, including those involving NTRK1, NTRK2, and NTRK3. Similarly, the Oncomine™ Comprehensive Assay by ThermoFisher covers 161 cancer associated genes and simultaneously interrogates DNA and RNA using Ion Torrent technology.[49] Since the Oncomine™ assay relies on amplicon-based technology, knowledge of both fusion partners must be known. Although all currently known NTRK fusion partners are included and additional revisions to the assay are constantly in development, one consideration with this platform is that it may miss novel or previously unreported fusions.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR DISEASE MONITORING: TREATMENT AND RESISTANCE MECHANISMS

As seen in treatment with other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, acquired resistance has been shown to develop for patient with NTRK fusions who receive small molecular inhibitor therapy. Some recent studies have observed the development of point mutations in the kinase domains, p.G667C in TrkA/NTRK1 and p.G696A in TrkC/NTRK3.[5, 50, 51] The efficacy of larotrectinib is reduced in tumors that harbor these NTRK mutations or amplification of the fusion gene.[52] Sequencing of lesions demonstrating progression after Trk inhibitor therapy should therefore include the aforementioned regions within the kinase domain, as second generation Trk inhibitors are currently in clinical trials to try to extend the treatment response.[53]

Assessing circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has been shown to be an effective non-invasive method for monitoring for tumor recurrence and progression, and studies have demonstrated its use for monitoring tumors with oncogenic fusions.[50, 54, 55] Such methods may be used to monitor patients with solid tumors with NTRK fusions who are either progressing on therapy or do not have sufficient tumor material for initial testing. One caveat, however, is that some sensitivity issues have been identified when only monitoring ctDNA. In two recent meta-analyses, for example, ctDNA analysis was only 67% sensitive for detecting KRAS alterations in a colon cancer cohort, and 67% sensitive for detecting EGFR p.T790M point mutations in a lung cancer cohort.[56, 57] Detection of gene fusions may even be more difficult, as a recent study showed only 54% sensitivity for detecting ALK fusions in ctDNA from patients with lung cancer.[58] Finally, it should also be noted that the currently most widely used platforms for ctDNA sequencing may not be effective for monitoring patients with NTRK fusions. The Guardant360® assay can identify point mutations in NTRK1 and NTRK3, but only fusions involving NTRK1 can be detected,[59] while the FoundationOne Liquid assay does not interrogate any of the NTRK genes or ETV6.[60]

CONCLUSIONS

Oncogenic NTRK fusions are seen in many cancer types. They are common in select rare tumor types while rare in common tumors. Identification of these fusions may provide important therapeutic opportunities for patients with advanced or unresectable cancers. Appropriate screening and/or confirmation of NTRK fusions depends on the tumor type and available material.

Developing an appropriate algorithm for testing patient samples will be dependent on the resources available as well as specific patient scenarios. Close communication between oncologists and pathologists is key. At Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, we use a combination of IHC, FISH, DNA-based sequencing, and RNA-based sequencing depending on the clinical situation and histologic findings. If a rare tumor type that commonly exhibits an NTRK fusion is suspected, such as infantile fibrosarcoma or secretory carcinoma, then NTRK3 FISH is performed for diagnostic confirmation and eligibility for Trk inhibitor therapy. In advanced-stage patients with common malignancies that rarely exhibit NTRK fusions (e.g., lung adenocarcinoma, colon adenocarcinoma, etc.), DNA-based sequencing with MSK-IMPACT is performed to simultaneously screen for MAPK pathway alterations such as RAS/BRAF mutations and fusions, microsatellite instability, and copy number changes such as HER2 amplification. Cases with structural variants of uncertain significance and RAS/BRAF wild-type cases involving tumor types that are often driven by MAPK pathway activation, such as colon or lung adenocarcinoma, are reflexed to an RNA-based NGS assay for further fusion analysis. Pan-Trk IHC is often also used when NTRK rearrangements of uncertain significance are detected by MSK-IMPACT or when MSK-IMPACT testing is not an option due to insufficient material or low tumor content.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Marc Ladanyi for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) under the Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748) awarded to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

The authors have the following potential conflicts of interest to disclose: J.F.H. has received honoraria from Medscape, Cor2Ed, and Axiom Biotechnologies as well as research funding from Bayer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vaishnavi A, Le AT, and Doebele RC, TRKing down an old oncogene in a new era of targeted therapy. Cancer Discov, 2015. 5(1): p. 25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donovan MJ, et al. , Neurotrophin and neurotrophin receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells. Regulation of expression in response to injury. Am J Pathol, 1995. 147(2): p. 309–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holtzman DM, et al. , TrkA expression in the CNS: evidence for the existence of several novel NGF-responsive CNS neurons. J Neurosci, 1995. 15(2): p. 1567–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kheder ES and Hong DS, Emerging Targeted Therapy for Tumors with NTRK Fusion Proteins. Clin Cancer Res, 2018. 24(23): p. 5807–5814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cocco E, Scaltriti M, and Drilon A, NTRK fusion-positive cancers and TRK inhibitor therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2018. 15(12): p. 731–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourgeois JM, et al. , Molecular detection of the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion differentiates congenital fibrosarcoma from other childhood spindle cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol, 2000. 24(7): p. 937–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knezevich SR, et al. , A novel ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion in congenital fibrosarcoma. Nat Genet, 1998. 18(2): p. 184–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasudev P and Onuma K, Secretory breast carcinoma: unique, triple-negative carcinoma with a favorable prognosis and characteristic molecular expression. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 2011. 135(12): p. 1606–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skalova A, et al. , Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, containing the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene: a hitherto undescribed salivary gland tumor entity. Am J Surg Pathol, 2010. 34(5): p. 599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tognon C, et al. , Expression of the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion as a primary event in human secretory breast carcinoma. Cancer Cell, 2002. 2(5): p. 367–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiang S, et al. , NTRK Fusions Define a Novel Uterine Sarcoma Subtype With Features of Fibrosarcoma. American Journal of Surgical Pathology, 2018. 42(6): p. 791–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, et al. , Identification of NTRK3 Fusions in Childhood Melanocytic Neoplasms. J Mol Diagn, 2017. 19(3): p. 387–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lezcano C, et al. , Primary and Metastatic Melanoma With NTRK Fusions. Am J Surg Pathol, 2018. 42(8): p. 1052–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alassiri AH, et al. , ETV6-NTRK3 Is Expressed in a Subset of ALK-Negative Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumors. Am J Surg Pathol, 2016. 40(8): p. 1051–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu T, et al. , Gene Fusion in Malignant Glioma: An Emerging Target for Next-Generation Personalized Treatment. Transl Oncol, 2018. 11(3): p. 609–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson SD, et al. , Targetable Gene Fusions Associate With the IDH Wild-Type Astrocytic Lineage in Adult Gliomas. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, 2018. 77(6): p. 437–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farago AF, et al. , Clinicopathologic Features of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring an NTRK Gene Fusion. JCO Precis Oncol, 2018. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pietrantonio F, et al. , ALK, ROS1, and NTRK Rearrangements in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2017. 109(12). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brzezianska E, et al. , Molecular analysis of the RET and NTRK1 gene rearrangements in papillary thyroid carcinoma in the Polish population. Mutat Res, 2006. 599(1–2): p. 26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greco A, Miranda C, and Pierotti MA, Rearrangements of NTRK1 gene in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2010. 321(1): p. 44–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ricarte-Filho JC, et al. , Identification of kinase fusion oncogenes in post-Chernobyl radiation-induced thyroid cancers. J Clin Invest, 2013. 123(11): p. 4935–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Food and Drug Administration, FDA approves an oncology drug that targets a key genetic driver of cancer, rather than a specific type of tumor [FDA news release]. 2018: Accessed at: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm626710.htm.

- 23.Drilon A, et al. , What hides behind the MASC: clinical response and acquired resistance to entrectinib after ETV6-NTRK3 identification in a mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC). Ann Oncol, 2016. 27(5): p. 920–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drilon A, et al. , Safety and Antitumor Activity of the Multitargeted Pan-TRK, ROS1, and ALK Inhibitor Entrectinib: Combined Results from Two Phase I Trials (ALKA-372–001 and STARTRK-1). Cancer Discov, 2017. 7(4): p. 400–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farago AF, et al. , Durable Clinical Response to Entrectinib in NTRK1-Rearranged Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol, 2015. 10(12): p. 1670–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drilon A, et al. , Efficacy of Larotrectinib in TRK Fusion-Positive Cancers in Adults and Children. N Engl J Med, 2018. 378(8): p. 731–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cocco E, et al. , Colorectal carcinomas containing hypermethylated MLH1 promoter and wild type BRAF/KRAS are enriched for targetable kinase fusions. Cancer Research, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gatalica Z, et al. , Molecular characterization of cancers with NTRK gene fusions. Mod Pathol, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hechtman JF, et al. , Pan-Trk Immunohistochemistry Is an Efficient and Reliable Screen for the Detection of NTRK Fusions. Am J Surg Pathol, 2017. 41(11): p. 1547–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudzinski ER, et al. , Pan-Trk Immunohistochemistry Identifies NTRK Rearrangements in Pediatric Mesenchymal Tumors. American Journal of Surgical Pathology, 2018. 42(7): p. 927–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hung YP, Fletcher CDM, and Hornick JL, Evaluation of pan-TRK immunohistochemistry in infantile fibrosarcoma, lipofibromatosis-like neural tumour and histological mimics. Histopathology, 2018. 73(4): p. 634–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brodeur GM, et al. , Trk receptor expression and inhibition in neuroblastomas. Clin Cancer Res, 2009. 15(10): p. 3244–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Connor A, et al. , Mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary gland origin with the ETV6 gene rearrangement by FISH: expanded morphologic and immunohistochemical spectrum of a recently described entity. Am J Surg Pathol, 2012. 36(1): p. 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto H, et al. , ALK, ROS1 and NTRK3 gene rearrangements in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours. Histopathology, 2016. 69(1): p. 72–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skalova A, et al. , Mammary Analogue Secretory Carcinoma of Salivary Glands: Molecular Analysis of 25 ETV6 Gene Rearranged Tumors With Lack of Detection of Classical ETV6-NTRK3 Fusion Transcript by Standard RT-PCR: Report of 4 Cases Harboring ETV6-X Gene Fusion. Am J Surg Pathol, 2016. 40(1): p. 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Church AJ, et al. , Recurrent EML4-NTRK3 fusions in infantile fibrosarcoma and congenital mesoblastic nephroma suggest a revised testing strategy. Modern Pathology, 2018. 31(3): p. 463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tannenbaum-Dvir S, et al. , Characterization of a novel fusion gene EML4-NTRK3 in a case of recurrent congenital fibrosarcoma. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud, 2015. 1(1): p. a000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zehir A, et al. , Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med, 2017. 23(6): p. 703–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Middha S, et al. , Reliable Pan-Cancer Microsatellite Instability Assessment by Using Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Data. JCO Precis Oncol, 2017. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sigal DS, et al. , Comprehensive genomic profiling identifies novel NTRK fusions in neuroendocrine tumors. Oncotarget, 2018. 9(88): p. 35809–35812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beadling C, et al. , A Multiplexed Amplicon Approach for Detecting Gene Fusions by Next-Generation Sequencing. J Mol Diagn, 2016. 18(2): p. 165–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang L, et al. , Identification of a novel, recurrent HEY1-NCOA2 fusion in mesenchymal chondrosarcoma based on a genome-wide screen of exon-level expression data. Genes Chromosomes Cancer, 2012. 51(2): p. 127–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng Z, et al. , Anchored multiplex PCR for targeted next-generation sequencing. Nat Med, 2014. 20(12): p. 1479–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu G, et al. , Diagnosis of known sarcoma fusions and novel fusion partners by targeted RNA sequencing with identification of a recurrent ACTB-FOSB fusion in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma. Mod Pathol, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lam SW, et al. , Molecular Analysis of Gene Fusions in Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors by Anchored Multiplex PCR-Based Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing. J Mol Diagn, 2018. 20(5): p. 653–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hrdlickova R, Toloue M, and Tian B, RNA-Seq methods for transcriptome analysis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA, 2017. 8(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy DA, et al. , Detecting Gene Rearrangements in Patient Populations Through a 2-Step Diagnostic Test Comprised of Rapid IHC Enrichment Followed by Sensitive Next-Generation Sequencing. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol, 2017. 25(7): p. 513–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Du T, et al. , Analytical performance of TruSight® Tumor 170 in the detection of gene fusions and splice variants using RNA from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) solid tumor samples [abstract]. Cancer Research, 2017. 77 ((13 Suppl): Abstract nr 565.). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams HL, et al. , Validation of the Oncomine() focus panel for next-generation sequencing of clinical tumour samples. Virchows Arch, 2018. 473(4): p. 489–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Russo M, et al. , Acquired Resistance to the TRK Inhibitor Entrectinib in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov, 2016. 6(1): p. 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lange AM and Lo HW, Inhibiting TRK Proteins in Clinical Cancer Therapy. Cancers, 2018. 10(4): p. 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hong DS, et al. , Larotrectinib in adult patients with solid tumours: a multicentre, open-label, phase I dose-escalation study. Ann Oncol, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Drilon A, et al. , A Next-Generation TRK Kinase Inhibitor Overcomes Acquired Resistance to Prior TRK Kinase Inhibition in Patients with TRK Fusion-Positive Solid Tumors. Cancer Discov, 2017. 7(9): p. 963–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liang W, et al. , Metastatic EML4-ALK fusion detected by circulating DNA genotyping in an EGFR-mutated NSCLC patient and successful management by adding ALK inhibitors: a case report. BMC Cancer, 2016. 16: p. 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang V, et al. , CD74-ROS1 Fusion in NSCLC Detected by Hybrid Capture-Based Tissue Genomic Profiling and ctDNA Assays. J Thorac Oncol, 2017. 12(2): p. e19–e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hao YX, et al. , Effectiveness of circulating tumor DNA for detection of KRAS gene mutations in colorectal cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther, 2017. 10: p. 945–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Passiglia F, et al. , The diagnostic accuracy of circulating tumor DNA for the detection of EGFR-T790M mutation in NSCLC: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 13379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cui S, et al. , Use of capture-based next-generation sequencing to detect ALK fusion in plasma cell-free DNA of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(2): p. 2771–2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guardant Health. 2017. Guardant360 Gene List. Obtained at: http://www.guardant360.com/.

- 60.Foundation Medicine. Technical Specifications. 2018. Obtained at: https://assets.ctfassets.net/vhribv12lmne/3SPYAcbGdqAeMsOqMyKUog/d0eb51659e08d733bf39971e85ed940d/F1L_TechnicalInformation_MKT-0061-04.pdf.