Abstract

Rationale:

Sporadic reports of alcohol consumption being linked to menstrual cycle phase highlight the need to consider hormonally-characterized menstrual cycle phase in understanding the sex-specific effects of risk for alcohol drinking in women.

Objectives:

We investigated the association between menstrual cycle phase, characterized by circulating progesterone and menses, with accurate daily alcohol intakes in rhesus monkeys, and the contribution of progesterone derived neuroactive steroids to cycle-related alcohol drinking.

Methods:

Menses (daily) and progesterone (2–3x/week) were obtained in female monkeys (n=8, 5 ethanol, 3 control) for 12–18 months. Ethanol monkeys were then induced to drink ethanol (4% w/v; 3 months) and given 22 hrs/day access to ethanol and water for approximately one year. In selected cycles, a panel of neuroactive steroids were assayed during follicular and luteal phases from pre-ethanol and ethanol exposure.

Results:

There were minimal to no effects of ethanol on menstrual cycle length, progesterone levels, follicular or luteal phase length. The monkeys drank more ethanol during the luteal phase, compared to the follicular phase, and ethanol intake was highest in the late luteal phase when progesterone declines rapidly. Two neuroactive steroids were higher during the luteal phase versus the follicular phase, and several neuroactive steroids were higher in the pre- vs post-ethanol drinking menstrual cycles.

Conclusions:

This is the first study to show that normal menstrual cycle fluctuations in progesterone, particularly during the late luteal phase, can modulate ethanol intake. Two of 11 neuroactive steroids were selectively associated with the effect of cycle progesterone on ethanol drinking, suggesting possible links to CNS mechanisms of ethanol intake control.

Keywords: menstrual cycle, luteal phase, alcohol, female, progesterone, monkey, neurosteroid, self-administration

For more than 50 years, the menstrual cycle has been hypothesized to relate to episodic, cyclic patterns of self-reported ethanol drinking (Podolsky 1963; Belfer et al. 1971). However, studies in women have largely been inconclusive concerning menstrual cycle phase and drinking. In social drinkers, ethanol consumption varies across the menstrual cycle in some studies (Harvey and Beckman 1985; Mello et al. 1990; DiMatteo et al. 2012) but not others (Sutker et al. 1983; Griffin et al. 1987; Holdstock and de Wit 2000). Overall, the inconsistent effects of menstrual cycle on alcohol consumption is likely due to variations in the history of alcohol intake and less accurate characterization of menstrual cycles (Carroll et al. 2015). Of the few human studies that address the effect of menstrual cycle on alcohol drinking, most assess fewer than three menstrual cycles or do not confirm menstrual cycle phase with physiologic measures. For example, Holdstock and de Wit (2000) found no effect of menstrual cycle phase on ethanol consumption or its effects, but subjects were only assessed on a single day of one menstrual cycle. Also, Hay and colleagues (1984) found that women with high tolerance to alcohol were less accurate at estimating blood alcohol level during the middle of the menstrual cycle, but serum hormones were not measured to confirm stage of the cycle. In a recent review of alcohol consumption and menstrual cycle phase, Carroll and colleagues (2015) concluded there were 13 studies that contributed to the empirical literature on this topic, and no firm conclusions could be made on this association. Indeed, the major conclusions by the authors stated that an ideal design would incorporate repeated measures that verified stage of the menstrual cycle. To date, all human studies have addressed interactions of menstrual cycle phase only under acute ethanol intake. As a result, there are no long-term studies assessing the ethanol naïve state and subsequent chronic ethanol intake with hormonal characterization during the menstrual cycle despite mounting evidence that menstrual cycle phase and progesterone derivatives can play a role in ethanol sensitivity.

Ovarian hormones have been implicated in ethanol consumption (Carroll et al. 2015), including progesterone and its neuroactive steroid metabolite allopregnanolone (3α,5α-tetrahydroprogesterone, THP) (Finn et al. 2010; Helms et al. 2012). Neuroactive steroids, including endogenously produced neurosteroids, interact directly with membrane bound neurostransmitter receptors rather than through nuclear steroid receptors. The progesterone metabolites allopregnanolone and pregnanolone (3α,5β-THP) are potent positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors (Belelli and Lambert 2005). In macaque monkeys, fluctuations in endogenous progesterone are dependent on menstrual cycle phase as are the neuroactive progesterone metabolites. Further, physiologic levels of circulating progesterone are additive to the subjective effects of ethanol in macaque monkeys with menstrual cycles. For example, macaque monkeys in the luteal phase, when progesterone is elevated, were more sensitive to the discriminative stimulus of ethanol and the ethanol-like effects of allopregnanalone compared to the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (Grant et al. 1997; Green et al. 1999a). Therefore, it is plausible that ethanol consumption can vary with menstrual cycle phase due to changes in sensitivity to ethanol’s subjective effects mediated by progesterone and neuroactive progesterone derivatives.

The purpose and overall goal of this investigation was to conduct a longitudinal study, using a nonhuman primate model of oral ethanol self-administration, to assess chronic ethanol intake related to hormonally characterized menstrual cycle phase over dozens of cycles per subject. Female monkeys have similar menstrual cycle length and ovarian hormone fluctuations as humans (Wilks et al. 1979; Marshall 2001). Additionally, monkeys also show individual differences in ethanol intake similar to humans (Mello et al. 1990; Vivian et al. 2001; Jimenez and Grant 2017). We tested the hypothesis that chronic ethanol intake would vary in female monkeys based on stage of the menstrual cycle and serum progesterone levels. Further we explored a panel of 11 neuroactive steroids for associations with progesterone and ethanol intake.

Materials and methods

Animals

Eight female, Indian origin, rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) from the Oregon National Primate Research Center (ONPRC) breeding colony were enrolled in the study experimentally naïve. Five animals at age 45.6 ± 2.0 (SD) months underwent a pre-ethanol period (no ethanol exposure, 20 months duration) followed by an ethanol exposure period (daily access to ethanol, 15 months duration). An additional three female monkeys served as controls that began induction (maltose-dextrin, no ethanol) at the same time and were matched in age to the 5 ethanol monkeys (67.6 ± 3.0 months, Table 1). All monkeys were housed in standard primate caging (0.8 × 0.8 × 0.9 meters). An operant conditioning panel was mounted within each cage to permit food and fluid access. Lighting (11:13 hr), temperature (21–25°C), and humidity (30–70%) were maintained, and monkeys were weighed weekly and fed a ration of banana flavored pelleted chow (Test Diet, St. Louis, MO) with various fruits and vegetables supplemented daily. Water was available ad libitum except during the ethanol induction period. Each animal was trained to present a leg for conscious blood sampling while sitting at the front of the cage (Porcu et al. 2006). Blood samples were taken at 8:00 am, normally on Monday, Wednesday and Friday each week, and each animal’s vaginal area was swabbed daily to detect onset and duration of menstruation. All animal procedures and experiments were approved by the ONPRC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and followed recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 2011). Additionally, ONPRC is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International.

Table 1: Experimental time line and group assignment of the 8 monkeys.

| Month | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 15 | 17 | 19 | 21 | 24 | 26 | 28 | 30 | 32 | 34 |

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 23 | 25 | 27 | 29 | 31 | 33 | 35 | |

| Ethanol cohort | Pre-ethanol phase (n=5) | Ethanol induction | “open access” self-administration (22 hrs/day) | ||||||||||||||

| Control cohort | Maltose-dextrin Yoked to an ethanol monkey (n=3) | ||||||||||||||||

Menstrual Cycles

Blood samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 20 minutes, and serum was stored at −20°C. Serum progesterone was measured by the Endocrine Core at ONPRC using the Cobas e411 electrochemiluminescence assay (Roche; Indianapolis, IN). Each menstrual cycle was defined from the first day of menses to the day prior to the onset of next menses. The follicular phase was defined from the onset of menses to the estimated first day of the luteal phase. The first day of the luteal phase was set as 1–2 days before or the day of detectable progesterone (>0.03 ng/ml) that was below 1–2 ng/ml (Clark et al. 1978; Ellinwood et al. 1984). The last day of the luteal phase was defined as the day prior to onset of next menses. Progesterone of >4 ng/ml was defined as normal luteal phase progesterone (Wilks et al. 1979). The luteal phase was further divided using the day of peak progesterone (pre-peak vs. post-peak). Menstrual cycles without progesterone >1 ng/ml were considered to be anovulatory (Wilks et al. 1979; Walker et al. 1983; Dailey and Neill 1981). Menstrual cycles were also identified as being within the breeding season (September – February) or outside the breeding season (March – August), since time of year is known to affect ovarian function in rhesus monkeys (Walker et al. 1983; Dailey and Neill 1981; Magden et al. 2015).

Ethanol Self-Administration

Following their menstrual cycle characterization during the pre-ethanol phase, the ethanol monkeys (n=5) were induced to drink 4% (w/v) ethanol diluted in water as previousy described (Grant et al. 2008a). Briefly, using a schedule-induced polydipsia procedure, at 30 day intervals, the daily ethanol intake was increased from 0.5 to 1.0 to 1.5 g/kg/day. After induction, drinkers had “open access” to concurrently available ad libitum water and 4% ethanol (via two different drinking spouts) for 22 hrs/day. Control animals drank the equivalent of a maltose dextrin (BioServ; Flemington, NJ) solution as an isocaloric control for ethanol in a volume yoked to an ethanol monkey of similar body weight. The remaining two hours per day were used for cage cleaning and replenishment of food, water, ethanol or maltose dextrin. Food and fluid intakes were time-stamped via a computer with customized hardware and programming on a National Instruments interface and Labview software (Austin, TX). Water and ethanol intake (g/kg) were calculated for each day. The 22 hr open access period lasted 344 days. The self-administration protocol included a three week phase where the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis was challenged with various pharmacological treatments to assess endocrine response (Porcu et al., 2006). Progesterone was not assessed during this time nor was ethanol intake included in analysis. These HPA challenges occurred prior to ethanol induction and at 6 months and 12 months after access to ethanol for 22 hrs/day.

Neuroactive Steroid and Estradiol Analysis via Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

A total of 40 serum steroid samples (200 μL) from the 5 ethanol monkeys, representing mid-luteal (progesterone peak) and the subsequent early/mid follicular phases of two menstrual cycles from the preethanol and ethanol drinking phases of the study, were assayed for neuroactive steroid levels from the same aliquot as was used for progesterone. Due to the pilot nature of extending the progesterone analysis to neuroactive steroids, the ethanol cycles chosen for analyses were those that showed a clear increase in ethanol self-administration after peak progesterone in the luteal phase. The GC-MS methodology (Jensen et al. 2017; Snelling et al., 2014) allows for the simultaneous quantification of estradiol and 10 neuroactive steroids: the 3α,5α-/3α,5β-reduced metabolites of progesterone, testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and deoxycorticosterone (DOC) as well as the precursors pregnenolone and DHEA. In addition, estradiol was added on the single quadrupole mass filter platform using an internal standard of 10 ng of 2-fluoroestradiol instead of estradiol-d5 due to the addition of estradiol-d0 as an eleventh target analyte. The accuracy and reproducibility of the updated method was confirmed by first spiking deionized water (300 μL) with either 70, 300, or 700 pg of the eleven target analytes and observing r2 values that ranged from 0.9888 to 0.9997 of the obtained amounts for all eleven steroids. Second, nine preliminary samples of female monkey serum (3 samples each at early follicular, estradiol peak, and progesterone peak) were analyzed, and estradiol levels matched nearly identically to the values from the ONPRC Endocrine Core. Samples in the early follicular phase with estradiol < 5 pg/mL were not quantifiable in the GC-MS or electrochemiluminescence assay (not shown). Analysis of samples and calibration curves were performed as previously reported (Jensen et al. 2017; Snelling et al. 2014). Further methodolical details are available upon request.

Statistical Analysis

All menstrual cycles were included in analysis for menstrual cycle length even if progesterone data were not available (n=235). Only cycles with progesterone >1 ng/mL (n=166 cycles) were included for analysis of follicular phase and luteal phase length. Daily ethanol and water intakes were averaged for the various menstrual cycle phases. Due to the variation in length of phases between animals and between menstrual cycles, intake was not assessed using area under the curve (AUC). All data are described using standard error of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise noted, and most statistics were performed using SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC). Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05, and p<0.10 was considered a statistical trend.

Effect size estimates (Cohen 1988) were calculated. For data based on differences between means and standard deviations, d=0.2 is considered a small effect, d=0.5 a medium effect, and d=0.8 a large effect. For data based on Pearson correlation, this parameter of effect size is denoted by the r value (Cohen, 1988); the effect size is low if the r value varies around 0.1, medium if r varies around 0.3, and large if r varies more than 0.5.

Ethanol and control monkeys cycle characteristics prior to the ethanol exposure:

Full cycle length and follicular phase length were not normally distributed, and a Wilcoxon-two sample test was used to compare pre-ethanol cycles in the drinkers versus (vs) the nondrinker controls. Luteal phase length was normally distributed and subjected to independent samples t-test. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare percent of normal and abnormal cycles between pre-ethanol and control cycles.

Pre-ethanol vs ethanol menstrual cycle comparison:

A chi-square test was performed to analyze the percent of normal and abnormal (progesterone < 4 ng/ml) menstrual cycles. Menstrual cycle and follicular phase length were assessed by Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test while luteal phase length was assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) between pre-ethanol and ethanol cycles.

Seasonal effects on menstrual cycle and drinking status:

A linear mixed model with menstrual cycle phase and breeding season as independent variables, repeated measures, with monkey as the subject variable was used to assess effect on progesterone AUC, ethanol intake, and water intake. Luteal phase progesterone AUC was calculated using the trapezoidal rule. Serum samples with undetectable progesterone were set at the limit of detection of the assay for analysis.

Ethanol intake and menstrual cycle phase:

Average ethanol intake for drinkers during the follicular phase, pre-peak progesterone luteal phase, and post peak progesterone luteal phase were compared within subject by one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey test. These same data were compared across subjects using a linear mixed model and post-hoc Tukey test.

Analysis of neuroactive steroids:

Target ion peaks were integrated in ChemStation and interpolated using Prism6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA), and the interpolated values were used to calculate mean pg/mL of analyte per extracted sample. Levels of analyte by cycle phase were compared by ANOVA with pre-ethanol vs ethanol drinking as a repeated measures factor, using Systat 11 (Richmond, CA). Pearson’s correlations explored associations with ethanol intake and with progesterone levels.

Results

Pre-ethanol and Control Menstrual Cycles

The total number of menstrual cycles characterized in this comparison was 154 across the 8 monkeys. One ethanol monkey during the pre-ethanol phase (#10074) and one control monkey (#10188) had abnormal menstrual cyclicity that was characterized by prolonged menstrual cycle length and/or blunted to non-detectable progesterone (<20% normal cycles in both animals). These animals were included in data analysis. However, monkey #10074 was not hormonally mature until late in the pre-ethanol phase, and only two cycles revealed an active corpus luteum despite menstruation occurring sometimes at normal intervals. Menstrual cycle data for individual animals are provided in Table 2 and Table 3. Preethanol and control menstrual cycles did not differ between groups for menstrual cycle length (33±2 days, n=102 cycles; 30±2 days, n=52 cycles; Z=0.54), luteal phase length (16±0 days, n=76 cycles; 15±1 days, n=31 cycles; t(105) = −0.9), and percent of normal cycles (66% and 56% respectively, p=0.31). Follicular phase length was greater in the control (17±3 days, n=31 cycles) compared to pre-ethanol (14±1 days, n=76 cycles) cycles (Z=2.4, p=0.02; d=0.23). The slightly longer average follicular phase length in the control group was possibly due to seasonal effects and relocation from outdoor housing prior to beginning study.

Table 2: Menstrual Cycle Parameters for Individual Animals.

Menstrual cycle parameters for individual animals during control and ethanol exposure. Menstrual cycle, follicular phase and luteal phase length are described as days +/− SEM. There were no significant differences between pre-ethanol and ethanol cycles in the drinkers for each of these parameters with the exception of two animals having shorter follicular phases during ethanol exposure.

| Pre-Ethanol | Ethanol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal | Days | n | Days | n | |

| Cycle length | Drinkers | ||||

| 10072 | 25±0 | 27 | 25±0 | 19 | |

| 10077 | 36±4 | 18 | 29±1 | 16 | |

| 10074 | 55±14 | 12 | 29±2 | 16 | |

| 10075 | 26±1 | 26 | 26±0 | 17 | |

| 10073 | 34±2 | 19 | 37±2 | 13 | |

| Controls | |||||

| 10187 | 28±2 | 18 | NA | NA | |

| 10188 | 35±6 | 15 | NA | NA | |

| 10186 | 29±1 | 19 | NA | NA | |

| Follicular Phase | Drinkers | ||||

| 10072 | 10±0 | 26 | 10±0 | 15 | |

| *10077 | 22±7 | 8 | 11±1 | 14 | |

| **10074 | 27±17 | 2 | 11±1 | 8 | |

| 10075 | 12±2 | 23 | 10±0 | 14 | |

| 10073 | 19±2 | 17 | 17±2 | 8 | |

| Controls | |||||

| 10187 | 16±3 | 10 | NA | NA | |

| 10188 | 25±9 | 9 | NA | NA | |

| 10186 | 11±1 | 12 | NA | NA | |

| Luteal Phase | Drinkers | ||||

| 10072 | 15±0 | 26 | 15±0 | 15 | |

| 10077 | 18±1 | 8 | 18±1 | 14 | |

| **10074 | 17±1 | 2 | 15±0 | 8 | |

| 10075 | 15±1 | 23 | 15±0 | 14 | |

| 10073 | 16±1 | 17 | 18±1 | 8 | |

| Controls | |||||

| 10187 | 14±1 | 10 | NA | NA | |

| 10188 | 13±1 | 9 | NA | NA | |

| 10186 | 18±1 | 12 | NA | NA | |

Animal #10077 had significantly longer follicular phases during pre-ethanol cycles (Z=1.7, p=0.0449) likely due to breeding season effects followed by acclimation to the standard light cycle during the ethanol exposure cycles resulting in shorter follicular phase length.

Animal #10074 was apparently not sexually mature during the pre-ethanol study period as only 2 of 12 cycles were ovulatory. (NA=Not applicable).

Table 3. Percent of Normal Menstrual Cycles.

Normal ovulatory menstrual cycles were defined as having progesterone >4ng/ml during the luteal phase. Percent of normal cycles were not significantly different between the controls and drinkers. Also, percent of normal cycles were not significantly different between pre-ethanol and ethanol exposure cycles in the drinking group. (NA=not applicable)

| Pre-Ethanol | Ethanol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | |

| Drinkers | ||||

| 10072 | 100 | 26 | 100 | 15 |

| 10077 | 41 | 17 | 57 | 14 |

| 10074 | 17 | 12 | 50 | 12 |

| 10075 | 84 | 25 | 87 | 15 |

| 10073 | 50 | 18 | 46 | 13 |

| Controls | ||||

| 10187 | 67 | 12 | NA | NA |

| 10188 | 10 | 10 | NA | NA |

| 10186 | 83 | 12 | NA | NA |

Ethanol Exposure Menstrual Cycles

Menstrual cycles during the ethanol induction period were included in analysis for the ethanol exposure cycles. Menstrual cycle length, luteal phase length and percent of normal cycles were not different between pre-ethanol and ethanol exposure in each of the drinkers (Tables 2 & 3). Animal #10074 trended toward shorter menstrual cycle length during the ethanol exposure cycles (Z=1.6, p=0.06, Table 2; d=0.75), but this was likely due to her irregular cyclicity during the pre-ethanol phase. Four of five drinkers had no significant difference in follicular phase length between pre-ethanol and ethanol drinking cycles. One animal (#10077) experienced prolonged follicular phases during the pre-ethanol cycles compared to the ethanol exposure cycles (Z=1.7, p=0.045, Table 2; d=0.77). Overall due to minimal effects of ethanol on menstrual cycle parameters, all pre-ethanol and ethanol cycles were combined to assess breeding season effects (183 cycles for cycle length and 135 cycles for follicular/luteal phase length). Breeding season had no effect on cycle, follicular phase, or luteal phase length in each of the drinkers with the exception of one animal (#10075) that experienced shorter luteal phases outside the breeding season [14±1 days vs. 16±0 days; F(1,35)=6.8, p=0.01; d=0.63], although still within normal limits for luteal phase length in rhesus monkeys (Walker et al. 1983; Dailey and Neill 1981).

Progesterone Levels

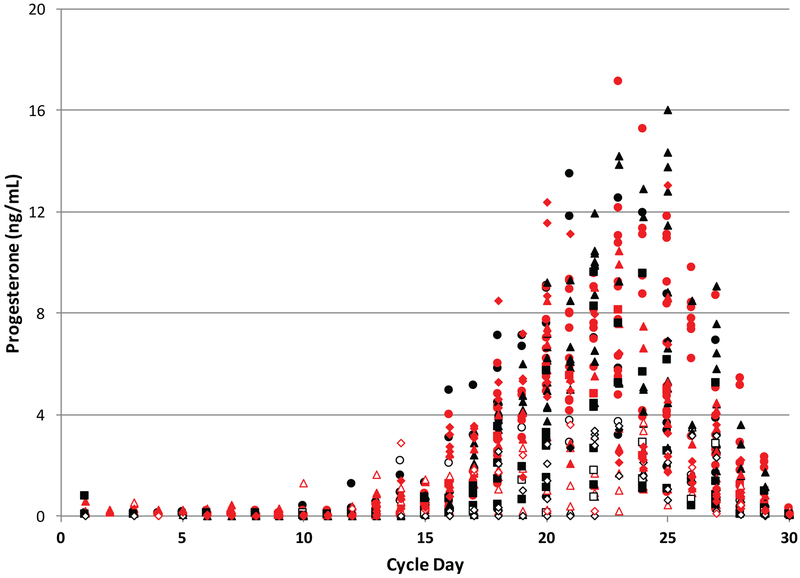

Monkeys overall showed normal progesterone levels and luteal phase length comparable to women during ovulatory cycles (Marshall 2001), but 18% of cycles had no active corpus luteum and 19% of cycles had progesterone <4 ng/ml during the control and pre-ethanol cycles. This percentage of abnormal cycles is similar to other reports in rhesus monkeys (Walker et al. 1983; Dailey and Neill 1981). Progesterone values for all control and pre-ethanol menstrual cycles with an active corpus luteum (n=106 cycles for n=8 animals) were normalized by labeling the last day of the luteal phase as day 30 of the cycle (Figure 1). Menstrual cycles >30 days in length only have the last 30 days of progesterone data depicted in Figure 1. One control monkey cycle was omitted due to lack of data for the luteal phase.

Figure 1.

Progesterone values for all control and pre-ethanol cycles (n=106) in 8 female rhesus monkeys that had an active corpus luteum with progesterone > 1ng/ml. Cycles were normalized by assigning the last day of the menstrual cycle as day 30. Each animal is identified by a symbol with a unique shape and color combination. Open symbols indicate cycles for that monkey with progesterone of < 4ng/ml.

In the ethanol group, progesterone AUC was assessed for all menstrual cycles including those during ethanol induction. Cycles were omitted from analysis if they were missing >2 progesterone sampling time points during the luteal phase. This resulted in 2 of 98 cycles being omitted during the preethanol phase and 4 of 69 cycles being omitted during the ethanol drinking phase. For anovulatory cycles with progesterone <1 ng/mL, AUC was determined using the average luteal phase length of normal cycles for that animal from the pre-ethanol period. There was no significant effect on progesterone AUC between pre-ethanol and ethanol exposure (45.4±3.2 and 38.6±2.7 ng*day/mL, respectively) and no interaction with breeding season. However, breeding season trended [F(1,4)=6.1, p=0.07; d=0.27] toward having higher progesterone AUC throughout the entire study (46.5±2.8 ng*day/mL, n=80; 38.9±3.4 ng*day/mL, n=81) and reached significance during the 22hr open access year (45.9±2.5 ng*day/mL, n=24; 30.1±4.0 ng*day/mL, n=27; F(1,4)=13.5, p=0.02; d=0.93). There was no correlation between progesterone AUC or peak progesterone and average ethanol intake of the luteal phase. Additionally, progesterone AUC was not correlated with average ethanol intake of the next follicular phase. Water intake also did not correlate with progesterone AUC.

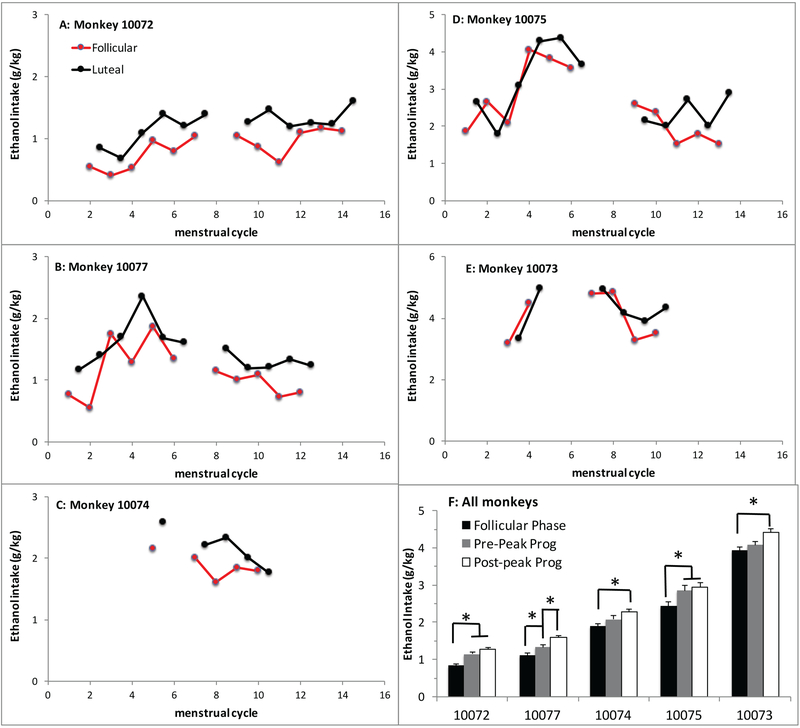

Ethanol Intake

During the 22 hr open access year, ethanol intakes averaged 1.1 to 4.0 g/kg/day (Figure 2). For the first analysis, average ethanol intake was compared across the follicular and luteal phases. Six of 51 cycles during the 22 hr access period were anovulatory with progesterone <1 ng/mL (all were outside the breeding season) so these cycles were omitted from comparison of ethanol intake across the cycle phases. Menstrual cycle phase and breeding season (45 cycles analyzed) were both assessed for effects on ethanol and water intake. There was a main effect of menstrual cycle phase on ethanol intake [F(1,4)=8.8, p=0.041] and a trend for breeding season [F(1,4)=5.5, p=0.08], but no interaction. Monkeys drank more ethanol during the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase (2.2±0.2 and 1.9±0.2 g/kg/day respectively, n=45 cycles, p=0.046; d=0.22) regardless of season. Average ethanol intakes for individual animals and individual menstrual cycle phases are provided in Figure 2. During the luteal phase, monkeys increased intake on average at least 0.25g/kg/day (approximately one drink/day; 17g ethanol/drink) in 58% of cycles and at least 0.5 g/kg/day (two drinks/day) in 36% of cycles. There was a trend for increased ethanol intake during the breeding season [F(1,4)=5.5, p=0.08; n=24 cycles] compared to the nonbreeding season (n=21 cycles) for both the follicular (2.1±0.3 and 1.6±0.2 g/kg/day; d=0.41) and luteal phase (2.4±0.3 and 2.0±0.2 g/kg/day; d=0.33). Lastly, there was no effect of menstrual cycle phase or breeding season on water intake.

Figure 2.

Average daily ethanol intake of each follicular phase (red) and luteal phase (black) during the 22 hr open access year for individual monkeys (Panels A-E). Follicular phase average ethanol intake precedes the luteal phase intake by an average of 14 days each cycle. Absent data points are due to menstrual cycles that had progesterone <1ng/ml or the HPA endocrine challenge that occurred 6 months into the 22 hr access year when progesterone and ethanol data were not analyzed. The y-axis is adjusted for the heavier drinkers in panels D-F. Panel F depicts average daily ethanol intake (+/− SEM) during follicular phase days, luteal phase days when progesterone was rising (Pre-Peak Prog), and luteal phase days when progesterone was falling (Post-Peak Prog). Asterisk * indicates differences between cycle phases for each animal (p<0.05).

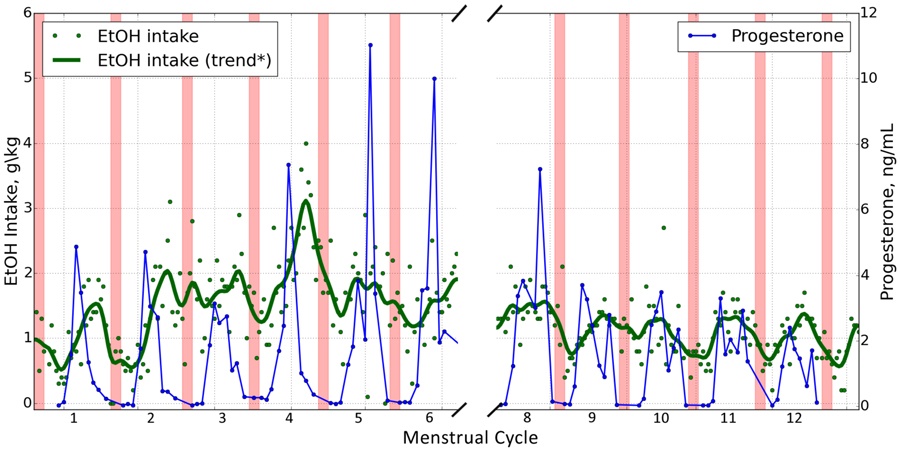

The luteal phase was further analyzed based on peak progesterone since rapid declines in circulating progesterone during the late luteal phase is linked to premenstrual dysphoric disorder and depression in women (Vigod et al. 2014; Mueller et al. 2014). Additionally, some women without a history of these disorders also have increases in ethanol intake during the premenstrum (Mello et al. 1990; Belfer et al. 1971). Average daily ethanol intake during follicular phase days (n=495 days) was compared to intake during luteal phase days when progesterone was increasing (pre-peak, n=308 days) and when progesterone was decreasing (post-peak, n=425 days) for the 45 ovulatory menstrual cycles of the 22 hr open access year (n=6 anovulation cycles omitted). Average daily ethanol intake across all drinkers was significantly higher [F(2,8)=70.7; p<0.0001; d=0.45] during post-peak progesterone days (2.3±0.1 g/kg/day) than both pre-peak progesterone (2.2±0.1 g/kg/day) and follicular phase days (2.0±0.1 g/kg/day). On average, ethanol consumption increased 17% and 30% respectively during pre-peak progesterone and post-peak progesterone portions of the luteal phase when compared to follicular phase ethanol intake. Figure 3 depicts a representative animal with peak ethanol intake occurring at the time of declining serum progesterone during the late luteal phase. Analysis of individual animals showed each drinker consumed significantly more ethanol during the post peak progesterone phase than follicular phase days (Figure 2F). Monkeys drank at least 0.1 g/kg/day more ethanol in 62% of cycles and at least 0.25 g/kg/day (one drink/day) in 40% of cycles during the post-peak progesterone portion of the luteal phase than pre-peak progesterone portion.

Figure 3.

Daily ethanol intake (green) and serum progesterone (blue) for representative animal #10077 throughout the 22 hr open access year. Red bars indicate menstruation. The x-axis break is during the HPA endocrine challenge that occurred 6 months into the 22hr access year when ethanol and progesterone data were not analyzed.

Neuroactive Steroid and Estradiol Levels

Serum samples from two menstrual cycles during the pre-ethanol phase and the ethanol phase of the five drinking monkeys were chosen for analysis of neuroactive steroid and estradiol levels (Table 4). Samples were restricted to the breeding season, and ethanol phase samples were chosen from cycles that showed the greatest rise in ethanol intakes during declining progesterone of the luteal phase. Levels of several neuroactive steroids were significantly higher in the pre-ethanol vs ethanol drinking cycles that were examined: pregnenolone [F(1,18)=4.7, p<0.05; d=0.74], 3α,5β-THDOC (tetrahydroDOC) [F(1,18)=25.6, p<0.001; d=1.4], 3α,5β-androstanediol [F(1,18)=6.6, p=0.02; d=0.85], and 3α,5α-androsterone [F(1,18)=9.99, p=0.005; d=0.86], with a trend for higher levels of DHEA during the pre-ethanol vs ethanol cycles [F(1,18)=3.1, p=0.096; d=0.60]. In addition to highly significant elevations in progesterone [F(1,18)=161.2, p<0.001; d=4.3] and estradiol in the luteal compared to the follicular phase samples, pregnanolone (3α,5β-THP) [F(1,18)=5.3, p<0.05; d=0.76], 3α,5β-THDOC [F(1,18)=6.5, p=0.02; d=0.66], and 3α,5α-androsterone [F(1,18)=14.2, p=0.001; d=0.96] were increased significantly in the luteal vs follicular phase. For, 3α,5α-androsterone, there was a significant interaction [F(1,18)=6.4, p<0.05], with post-hoc tests reflecting significantly higher luteal vs follicular levels during the pre-ethanol cycles (d=1.7). Serum levels of the remaining neuroactive steroids did not differ significantly between the luteal and follicular phases in the time points of the two pre-ethanol and ethanol menstrual cycles that were examined.

Table 4: Serum Neuroactive Steroid, Estradiol, and Progesterone Levels in Ethanol Drinking Monkeys.

Values are the mean ± SEM for serum samples from two menstrual cycles in the ethanol drinking monkeys (n=10/menstrual cycle phase) prior to the ethanol induction phase (Pre-Ethanol) and during open access to ethanol (Ethanol). The progesterone levels were analyzed by the Endocrine Core and are ng/mL; all other steroid levels were analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and are pg/mL. The progesterone and DOC derivatives are the most potent positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors identified. The testosterone and DHEA derivatives are positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors, with lower potency than the THPs and THDOCs.

| Pre-Ethanol | Ethanol | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid or Neuroactive Steroid | Parent Steroid | Activity at GABAA Receptors | Early/mid-follicular levels | Mid-luteal levels | Early/mid-follicular levels | Mid-luteal levels |

| Estradiol | n/a | None | nq | 88 ± 7 | nq | 95±10 |

| Progesterone | n/a | None | 0.7±0.02 | 6.6±0.6*** | 0.2±0.1 | 6.3±0.7*** |

| Pregnenolone | n/a | None | 629±50# | 697±51# | 578±47 | 485±73 |

| DHEA | n/a | Negative allosteric modulator | 4,234±183+ | 4,354±178+ | 3,698±245 | 3,519±656 |

| Allopregnanolone (3α,5α-THP) | Progesterone | Potent positive allosteric modulator | 1,364±87 | 1,331±77 | l,290±96 | 1,437±134 |

| Pregnanolone (3α,5β-THP) | Potent positive allosteric modulator | 994±90 | 1,116±95* | 852±31 | l,070±42* | |

| 3α,5α-THDOC | DOC | Potent positive allosteric modulator | 833±91 | 655±58 | 738±16 | 712±20 |

| 3α,5β-THDOC | DOC | Potent positive allosteric modulator | 425±48### | 553±37*,### | 320±11 | 357±11* |

| 3α,5α-Androstanediol | Testosterone | Positive allosteric modulator | 2,487±148 | 2,379±43 | 2,232±74 | 2,317±145 |

| 3α,5β-Androstanediol | Testosterone | Positive allosteric modulator | 2,164±105# | 2,275±96# | 1,957±93 | 1,889±145 |

| 3α,5β-Androsterone | DHEA | Positive allosteric modulator | l,502±76## | 1,856±53***,## | 1,465±45 | 1,521±46 |

| 3α,5β-Androsterone | DHEA | Positive allosteric modulator | 2,557±135 | 2,616±59 | 2,607±260 | 2,453±255 |

p<0.05,

p≤0.001 vs respective follicular phase, ANOVA main effect (effect size = 4.3 for progesterone, 0.76 for pregnanolone, and 0.66 for 3α,5β-THDOC) or post-hoc (effect size = 1.7 for 3α,5β-androsterone) when significant interaction

p<0.10,

p<0.05.

p<0.01,

p<0.001 vs respective post-ethanol phase, ANOVA main effect (effect size range = 0.74 – 1.4 for significant effects; 0.6 for trend)

Nq = not quantified, below level of detection in GC-MS assay; DHEA = dehydroepiandrosterone; DOC = deoxycorticosterone; THP = tetrahydroprogesterone; THDOC = tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone

Correlations determined that allopregnanolone (3α,5α-THP) levels tended to be positively correlated with average ethanol intake (r=0.39, p=0.09, n=20), consistent with choosing cycles for assay that showed a strong relationship between peak progesterone levels and ethanol intake reported above (Figures 2F and 3). Correlations between the other neuroactive steroids and ethanol intake were not significant (n=20/steroid). Likewise, estradiol levels were only dectectable during the luteal phase with the GC-MS assay, and the correlation with ethanol intake was not significant (n=10). Progesterone levels were significantly positively correlated with pregnanolone (3α,5β-THP; r=0.73, p=0.0003, n=20) levels and tended to be positively correlated with 3α,5β-THDOC levels (r=0.38, p=0.99, n=20). In contrast, progesterone levels were significantly negatively correlated during the luteal phase with 3α,5β-androstanediol levels (r=−0.72, p<0.02, n=10) and tended to be negatively correlated with 3α,5β-androsterone levels (r=−0.56, p=0.093, n=10).

Discussion

The results of this study add substantially to our understanding of the role of menstrual cycle phase, progesterone and its neuroactive metabolites in ethanol self-administration. Chronic ethanol drinking does not appear to alter global measures of characteristics (mensus, cycle length) or hormonal aspects of menstrual cycle using either a within-subject (pre- vs post-ethanol cycles) or a between subject (pre-ethanol vs control cycles) comparison. In contrast, the self-administration of ethanol was influenced by menstrual cycle phase. Across all levels of daily drinking, the monkeys undergoing chronic ethanol self-administration consumed more ethanol during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, when progesterone levels are elevated, compared to the follicular phase. Calculating a drink as 0.25 g/kg ethanol, fluctuations in ethanol intake equated to an increase of at least 1, 2 or 3 drinks/day during the luteal phase for 58, 31, and 15% of the 45 menstrual cycles analyzed, respectively.

Our analysis suggests that progesterone is a key hormone influencing voluntary ethanol consumption. The luteal phase is associated with increased risk and symptoms of depression, and there is a prevalent co-morbidity of depression and alcoholism, particularly in women (Amin et al. 2006; Goldstein et al. 2012). For example, in women with and without a family history of alcoholism, Evans and Levin (2011) found a more negative mood state during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. However, as shown in Figure 1, the luteal phase is dynamic in terms of progesterone levels, and the late luteal phase has been associated with various mood disorders such as premenstrual dysphoric disorder (Mueller et al. 2014). Here we show that monkeys drank more ethanol on days after progesterone had peaked and began to decrease in the luteal phase compared to all other phases of the menstrual cycle. Women have also reported increased ethanol intake during the late luteal phase, although the analysis did not extend beyond a single menstrual cycle (Mello et al. 1990; Belfer et al. 1971) and/or did not report progesterone levels (Carroll et al., 2015). For example, in a study of women “social drinkers”, those that drank more ethanol in the late luteal phase also reported more premenstrual negative subjective effects, a finding consistent with women reporting more of a “good drug effect” for ethanol consumption during the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase (Mello et al. 1990; Evans and Levin 2011). Overall, the rapidly declining progesterone level has led to the hypothesis that anxiolytic effects of ethanol may lead to women self-medicating during this particular time of the menstrual cycle that is characterized by increased negative mood state and risk for depressive disorders.

To address a possible mechanism of rapidly falling progesterone related to an increase in ethanol intake, we explored a panel of circulating neuroactive steroids in luteal compared to follicular phases. The neuroactive steroids allopregnanolone and pregnanolone are progesterone metabolites and the two most potent positive modulators of GABAA receptors identified to date (Belelli and Lambert, 2005; Helms et al. 2012; Finn and Purdy 2007; Finn and Jimenez 2017). Many behavioral effects of ethanol appear to be mediated through GABAA receptors (Finn and Jimenez 2017; Helms et al. 2012). For example, the exogenous administration of allopregnanolone and pregnanolone can substitute for the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol (Grant et al. 2008b), a behavior mediated by GABAA receptors in monkeys (Helms et al. 2009). In addition, female macaque monkeys were significantly more sensitive to ethanol and the ethanol-like effects of allopregnanolone during the luteal compared to the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (Grant et al. 1997; Green et al. 1999a). Likewise, in the present study, the neuroactive steroid pregnanolone was higher in the luteal phase than the follicular phase of our drinking monkeys, and allopregnanolone tended to be positively correlated with ethanol intake. Finally, along with the variations in ethanol sensitivity, global measures of GABA function appears to also vary with the menstrual cycle. A recent review of 11 studies investigating various subjective and performance measures of GABA inhibitory function (e.g., GABA levels vs transcranial magnetic stimulation measures) reported that women without premenstrual mood symptoms had higher GABA inhibition in the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase. In contrast, women suffering from mood symptoms had the opposite finding (Vigod et al. 2014).

It is interesting that a history of ethanol drinking did not significantly alter serum allopregnanolone or pregnanolone levels vs pre-ethanol levels in female rhesus monkeys in the present study, which differs from the significant reduction in plasma allopregnanolone levels observed following chronic ethanol drinking in male cynomolgus monkeys (Beattie et al. 2017). These results suggest that a long history of ethanol drinking may alter neurosteroid biosynthesis downstream of progesterone differently in male and female monkeys. The current findings also suggest that a history of ethanol drinking may suppress synthesis of pregnenolone, the 3α,5α-metabolite downstream of DHEA (androsterone), and the 3α,5β-metabolites downstream of testosterone (androstanediol) and DOC (THDOC). However, neuroactive steroid synthesis is a dynamic process; therefore, additional studies are necessary to further characterize the effects of ethanol drinking history on levels of many neuroactive steroids that likely work in concert to coordinate the physiological control of CNS excitability.

Variations in metabolism of ethanol associated with menstrual cycle phase have also been investigated as a cause for differences in ethanol intake; however, the results to date have been inconsistent. While Jones & Jones (1976) found increased blood ethanol concentration during the premenstrum compared to other phases of the menstrual cycle, this study did not measure sex hormones to confirm menstrual cycle phase, and other studies have not found similar results. Additional pharmacokinetic studies where menstrual cycle phase was confirmed by sex hormone analysis found conflicting results. No significant differences in ethanol metabolism were noted by Dettling et al. (2010) or Mumenthaler et al. (1999), while Sutker (1987) found faster elimination times during the mid-luteal phase. Studies performed in female macaques have also not found any differences in ethanol metabolism related to menstrual cycle phase (Green et al. 1999b; Mello et al. 1984). If ethanol metabolism is altered by sex hormones, then these fluctuations could play a role in ethanol sensitivity and drinking habits of women. On the other hand, increases in metabolizing enzymes due to ethanol consumption could alter circulating levels of reproductive hormones (Mendelson et al. 1988). Future studies are needed to assess how metabolism of ethanol may change and/or interact with menstrual cycle phase.

Although it appears that progesterone plays a role in ethanol intake, the effect on intake is not proportional to luteal phase-progesterone AUC or peak progesterone given the within-and between subject variability in these measures (Figures 2, 3). In addition, there are multiple factors that contribute to ethanol self-administration, even in this highly controlled environment with longitudinal measures. For example, the preliminary data on pregnanolone and allopregnanolone provide some evidence that progesterone metabolites, rather than progesterone itself, may play a role in ethanol consumption during the late luteal phase. In addition, progesterone was primarily obtained 3x/week; thus, the true peak in progesterone during the luteal phase could have been missed, resulting in lower AUC calculations. Further studies will help elucidate the relationship between progesterone, progesterone metabolites, and ethanol intake.

In summary, this is the first report in a primate species, human or nonhuman, of oral chronic ethanol intake and its relationship to extensively characterized menstrual cycles over many months within and between subjects. Whether subjects were low or heavy drinkers, all animals in this study consumed more average daily ethanol during the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. Additionally, the late luteal phase, when progesterone levels are rapidly decreasing, had the highest average ethanol intake. Future studies to determine the role of ovarian hormones, particularly progesterone and its GABAA receptor-modulating metabolites, on ethanol intake will provide important information in determining the mechanisms of ethanol self-administration, alcohol use disorders, and perhaps potential treatment options for alcoholism in women.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kevin Nusser for his expertise in animal training, Christa Helms for statistical analysis, Steve Gonzales for development of drinking panels and data analyses, the Endocrine Technology Support Core at the Oregon National Primate Research Center for assaying serum progesterone, and Aleksandr Salo for statistical and graphic contributions. This study was funded by AA013510, AA13641, AA109431 (KAG and EJB), OD11092, AA012439 (DAF) and facilities and resources at the VA Portland Health Care System (DAF). The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Amin Z, et al. (2006) The interaction of neuroactive steroids and GABA in the development of neuropsychiatric disorders in women. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 84(4):635–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie MC, Maldonado-Devincci AM, Porcu P, O’Buckley TK, Daunais JB, Grant KA, Morow AL (2017) Voluntary ethanol consumption reduces GABAergic neuroactive steroid (3α,5α)3-hydroxypregnan-20-one (3α,5α-THP) in the amygdala of the cynomolgus monkey. Addiction Biol 22:318–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfer ML, Shader RI, Carroll M, Harmatz JS (1971) Alcoholism in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 25(6):540–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D, Lambert JJ (2005) Neurosteroids: Endogenous regulators of the GABAA receptor. Nat Rev Neurosci 6:565–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll HA, Lustyk MK, Larimer ME (2015) The relationship between alcohol consumption and menstrual cycle: a review of the literature. Arch Womens Ment Health 18:773–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JR, Dierschke DJ, Wolf RC (1978) Hormonal regulation of ovarian folliculogenesis in rhesus monkeys: concentrations of serum luteinizing hormones and progesterone during laparoscopy and patterns of follicular development during successive menstrual cycles. Biol Reprod 18(5):779–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Dailey RA, Neill JD (1981) Seasonal variation in reproductive hormones of rhesus monkeys: anovulatory and short luteal phase menstrual cycles. Biol Reprod 25(3):560–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettling A, Preiss A, Skipp G, Haffner HT (2010) The influence of the luteal and follicular phases on major pharmacokinetic parameters of blood and breath alcohol kinetics in women. Alcohol 44(4):315–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo J, Reed SC, Evans SM (2012) Alcohol consumption as a function of dietary restraint and the menstrual cycle in moderate/heavy (“at-risk”) female drinkers. Eat Behav 13(3):285–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinwood WE, Norman RL, Spies HG (1984) Changing frequency of pulsatile luteinizing hormone and progesterone secretion during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle of rhesus monkeys. Biol Reprod 31(4):714–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Levin FR (2011) Response to alcohol in women: role of the menstrual cycle and a family history of alcoholism. Drug Alcohol Depend 114(1):18–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn DA, Purdy RH (2007) Neuroactive steroids in anxiety and stress In: Handbook of Contemporary Neuropharmacology, (Sibley D, Hanin I, Kuhar M and Skolnick P, eds.) John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, pp. 133–176. [Google Scholar]

- Finn DA, Beckley EH, Kaufman KR, Ford MM (2010) Manipulation of GABAergic steroids: Sex differences in the effects on alcohol drinking- and withdrawal-related behaviors. Horm Behav 57:12–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn DA, Jimenez VA (2017) Dynamic adaptation in neurosteroid networks in response to alcohol. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2017 Dec 15 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RB, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Grant BF (2012) Sex differences in prevalence and comorbidity of alcohol and drug use disorders: results from wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol Related Conditions. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 73(6):938–950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA, Azarov A, Shively CA, Purdy RH (1997) Discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol and 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one in relation to menstrual cycle phase in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Psychopharmacology 130(1):59–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA, Leng X, Green HL, Szeliga KT, Rogers LS, Gonzales SW (2008a) Drinking typography established by scheduled induction predicts chronic heavy drinking in a monkey model of ethanol self-administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32(10):1824–1838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA, Helms CM, Rogers LS, Purdy RH (2008b) Neuroactive steroid stereospecificity of ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects in monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 326(1):354–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KL, Azarov AV, Szeliga KT, Purdy RH, Grant KA (1999a) The influence of menstrual cycle phase on sensitivity to ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of GABAA-positive modulators. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 64(2):379–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KL, Szeliga KT, Bowen CA, Kautz MA, Azarov AV, Grant KA (1999b) Comparison of ethanol metabolism in male and female cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis). Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23(4):611–616 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin ML, Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Lex BW (1987) Alcohol use across the menstrual cycle among marihuana users. Alcohol 4: 457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey SM, Beckman LJ (1985) Cyclic fluctuation in alcohol consumption among female social drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 9(5):465–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay WM, Nathan PE, Heermans HW, Frankenstein W (1984) Menstrual cycle, tolerance and blood alcohol level discrimination ability. Addict Behav 9(1):67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms CM, Rogers LS, Grant KA (2009) Antagonism of the ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol, pentobarbital, and midazolam in cynomolgus monkeys reveals involvement of specific GABAA receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 331(1):142–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms CM, Rossi DJ, Grant KA (2012) Neurosteroid influences on sensitivity to ethanol. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 3:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdstock L, de Wit H (2000) Effects of ethanol at four phases of the menstrual cycle. Psychopharmacology 150(4):374–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen JP, Nipper MA, Helms ML, Ford MM, Crabbe JC, Rossi DJ, Finn DA (2017) Ethanol withdrawal-induced dysregulation of neurosteroid levels in plasma, cortex, and hippocampus in genetic animal models of high and low withdrawal. Psychopharmacology 234:2793–2811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez VA, Grant KA (2017) Studies using macaque monkeys to address excessive alcohol drinking and stress interactions. Neuropharmacology 122:127–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BM, Jones MK (1976) Alcohol effects in women during the menstrual cycle. Ann N Y Acad Sci 273:576–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magden ER, Mansfield KG, Simmons JH, Abee CR (2015) Nonhuman Primates In: Fox JG et al. (Eds) Laboratory Animal Medicine, 3rd edn. Elsevier, San Diego, pg 799 [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JC (2001) Hormonal regulation of the menstrual cycle and mechanisms of ovulation In: DeGroot LJ, Jameson JL (eds) Endocrinology, 4th edn. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 2073–2074 [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Bree MP, Skupny AS, Mendelson JH (1984) Blood alcohol levels as a function of menstrual cycle phase in female macaque monkeys. Alcohol 1(1):27–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Lex BW (1990) Alcohol use and premenstrual symptoms in social drinkers. Psychopharmacology 101(4):448–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson JH, et al. (1988) Acute alcohol effects on plasma estradiol levels in women. Psychopharmacology 94(4):464–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller SC, Grissom EM, Dohanich GP (2014) Assessing gonadal hormone contributions to affective psychopathologies across humans and animal models. Psychoneuroendocrinology 46:114–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumenthaler MS, Taylor JL, O’Hara R, Fisch HU, Yesavage JA (1999) Effects of menstrual cycle and female sex steroids on ethanol pharmacokinetics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23(2):250–255 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (2011) Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th edition, National Academies Press, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Podolsky E (1963) The woman alcoholic and premenstrual tension. J Am Med Womens Assoc 18:816–818 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcu P, Rogers LS, Morrow AL, Grant KA (2006) Plasma pregnenolone levels in cynomolgus monkeys following pharmacological challenges of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 84(4):618–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snelling C, Tanchuck-Nipper MA, Ford MM, Jensen JP, Cozzoli DK, Ramaker MJ, Helms M, Crabbe JC, Rossi DJ, Finn DA (2014) Quantification of ten neuroactive steroids in plasma in Withdrawal Seizure–Prone and –Resistant mice during chronic ethanol withdrawal. Psychopharmacology 231:3401–3414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutker PB, Libet JM, Allain AN, Randall CL (1983) Alcohol use, negative mood states, and menstrual cycle phases. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 7: 327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutker PB, Goist KC Jr, Kin AR (1987) Acute alcohol intoxication in women: relationship to dose and menstrual cycle phase. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 11(1):74–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigod SN, Strasburg K, Daskalakis ZJ, Blumberger DM (2014) Systematic review of gamma-aminobutyric-acid inhibitory deficits across the reproductive life cycle. Arch Womens Ment Health 17(2):87–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivian JA, Green HL, Young JE, Majerksy LS, Thomas BW, Shively CA, Tobin JR, Nader MA, Grant KA (2001) Induction and maintenance of ethanol self-administration in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis): Long-term characterization of sex and individual differences. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 25(8):1087–1097 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker ML, Gordon TP, Wilson ME (1983) Menstrual cycle characteristics of seasonally breeding rhesus monkeys. Biol Reprod 29(4):841–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilks JW, Hodgen GD, Ross GT (1979) Endocrine characteristics of ovulatory and anovulatory menstrual cycles in the rhesus monkey In: Hafez ESE (ed) Human Ovulation, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 205–218 [Google Scholar]