Abstract

In this review we summarize the research pertaining to the role of exercise in preventing cognitive decline in patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). Impairment in cognitive function, especially in executive function, is common in patients with ESKD, and may worsen with maintenance dialysis as a result of retention of uremic toxins, recurrent cerebral ischemia, and high burden of inactivity. Cognitive impairment may lead to long-term adverse consequences, including dementia and death. Home-based and intradialytic exercise training (ET) are among the non-pharmacologic interventions identified to preserve cognitive function in ESKD. Additionally, cognitive training (CT) is an effective approach recently identified in this population. While short-term benefits of ET and CT on cognitive function were consistently observed in patients undergoing dialysis, more studies are needed to replicate these findings in diverse populations including kidney transplant recipients with long-term follow-up to better understand the health and quality of life consequences of these promising interventions. ET as well as CT are feasible interventions that may preserve or even improve cognitive function for patients with ESKD. Whether these interventions translate to improvements in quality of life and long-term health outcomes, including dementia prevention and better survival, are yet to be determined.

INTRODUCTION

Aging of Population of Patients with End-Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD)

End-stage kidney disease (ESKD) is a growing public health challenge in the United States, with more than 640,000 adults suffering from this devastating chronic condition.1 With a growing prevalence of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, it is estimated that there will be >1 million ESKD patients by 2025.1 However, the burden of ESKD is not equally distributed across the age spectrum. There has been a continuous increase in the number of older adults (age ≥65 years) initiating hemodialysis (HD) in the US, and in 2014, 49.6% of patients initiating HD were older adults.1 Additionally, patients undergoing HD are living longer; the number of HD patients aged 85 and older has increased from 5,073 in 1996 to 24,231 in 2014.1 As kidney transplant (KT) has become a growing treatment option for older adults, and as patients live longer with a functioning graft, these demographic shifts have also been observed among KT recipients.2

Measures of Global Cognitive Function in Studies of ESKD

While large cohort studies of patients with ESKD rarely conduct a neurocognitive battery to assess multiple cognitive domains, such as attention, memory, language, visuospatial ability, and executive function, global cognitive function is often assessed using brief screening tools in prospective cohort studies.3–6 The most commonly studied tool to measure cognitive function in patients with ESKD is the Modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MS), a validated measure of global cognitive function7–9 based on responses to 15 components covering domains including temporal and spatial orientation, multi-stage commands, and recall; scores for the 3MS range from 0 to 100, where lower scores indicate worse cognition. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is another brief screening tool of global cognitive function that is increasingly being recognized as a better tool for its improvements in sensitivity in detecting mild cognitive impairment, but has only recently been studied in ESKD patients.6

Global Cognitive Function among Patients with ESKD

Dialysis patients have a high burden of global cognitive impairment even at younger ages,10–12 and patients undergoing HD of all ages have worse cognitive function than individuals of the same ages in the general population.4,13 In a cohort study of 324 adults aged 18 years and older initiating HD (mean age=55), the average (SD) 3MS score for global cognitive function was 89.8 (7.6),4 which parallels scores of the most cognitively vulnerable group of community-dwelling older adults aged 60 years and older.14 Many patients already have partially compromised cognition at dialysis initiation,15–17 which further declines while undergoing treatment,10,18–20 and often fluctuates from month to month.21 In fact, only 13% of prevalent HD patients were reported to have normal cognition22 and clinicians often fail to recognize declining cognition among patients who are undergoing HD23 or KT.6 In fact, physicians were found to only accurately identify HD patients and KT recipients 57%23 and 66%6 of the time, respectively. Yet, patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis (PD) have better cognitive functioning compared to those undergoing HD.24 Notably, however, chronic kidney disease patients with cognitive impairment are less likely to initiate PD and are more likely to have venous catheters at dialysis initiation.25

Among those undergoing KT, the prevalence of cognitive impairment is as high as 58% based on the MoCA.26 After restoration of kidney function, recipients may experience short-term improvements in cognitive function,3,27–32 regardless of age, sex, race, and frailty status.3 Despite these observed short-term improvements, a recent 4-year study of cognitive trajectories among KT recipients of all ages has demonstrated that some subgroups, particularly frail KT recipients, experience declines in cognitive functioning in the longer term, to the extent of reaching cognitive levels that were below their pre-KT levels on average.3

Executive Function among Patients with ESKD

Among the cognitive domains, executive function is most profoundly affected in adult ESKD patients.5 As a cognitive domain responsible for mental flexibility, set shifting, and complex problem solving, severe executive function impairment impedes HD patients’ ability to comply with their dialysis schedule, maintain complicated medication regimens for chronic conditions, retain the capacity for independence and self-care,33–35 make informed decisions, and adhere to fluid and dietary restrictions,23 leading to death.12,36

In the cohort study of 324 adults described above, psychomotor speed was measured by the time it took to complete the Trail Making Test Part A (TMTA) and executive function by subtracting Part A from Part B (TMTB-TMTA); longer times to complete this task reflected worse cognitive function. The mean (SD) time it took for those patients to finish the Trails-Making Test Part A and Trails-Making Test Part B for executive function and processing speed was 55 seconds (29) and 161 seconds (83), respectively;4 these mean times to complete these tasks are significantly worse compared to averages found for community-dwelling adults of the same age ranges.37 On average, HD patients suffer from a 3-fold higher rate of executive function impairment than the general population of the same ages.12,38 Furthermore, 38% of prevalent HD patients have severe impairments in executive function39 and it affects HD patients of all ages.39

Causes of Cognitive Impairment in Patients with ESKD

Elevated burden of stroke, subclinical cerebrovascular disease, arterial stiffness and central pressure in patients undergoing dialysis have been recognized as major catalysts impacting vulnerability to cognitive impairment.12,40–42 In addition, HD patients have a greater burden of white matter disease and cerebral atrophy.43 Yet, even though HD patients experience declines in executive function due to aging and cardiovascular disease, HD itself further impacts the decline. Executive function is the domain of cognition which is most impacted by HD initiation,11 though HD patients were often observed to experience deficits in multiple domains concurrently.44 In a cohort of 212 participants, transition to dialysis was associated with loss of executive function.11 HD independently leads to poor executive function through the retention of uremic toxins28,45 and by inducing recurrent cerebral ischemia.12,46 In terms of health behaviors, while undergoing HD, patients spend their dialysis session doing less cognitively challenging activities like sleeping (72.4%) and watching TV (87.9%), which leads to worse HRQOL, including mental HRQOL.47

Implications of Cognitive Impairment in Patients with ESKD

Impairment in cognitive function has several implications for patients with ESKD. For one, cognitive impairment prior to initiating dialysis was associated with lower odds of maintained functional status a year after dialysis initiation.48 Additionally, impairments in executive function in patients with ESKD may suggest early signs of dementia, particularly vascular dementia,49,50 and in many cases, Alzheimer’s disease.51,52 In a national study of 356,668 older patients initiating HD, the 5-year risk of diagnosed dementia accounting for the competing risk of death and HD withdrawal was 16% for women and 13% for men; the corresponding Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis risks were 2.6% for women and 2.0% for men.53 These older HD patients with a dementia diagnosis were at a 2-fold higher risk of subsequent mortality, as were those with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Additionally, older KT recipients, a group which is selected to be free of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, also have a higher burden of these conditions than community-dwelling adults, but lower than patients initiating HD.54 These older KT recipients with a diagnosis of dementia were then at elevated risk of both graft loss and mortality.54

While poor cognitive function has long been recognized for its adverse impact on survival in older adults generally55,56 and more recently this association has been observed in ESKD patients of all ages. Those who were cognitively impaired have between a 1.7- and 2.5-fold higher risk of mortality compared to their cognitively normal counterparts, independent of sociodemographic, clinical, and psychological factors.36,57 Additionally, mortality rates in HD patients with poor executive function are comparable to those with HD patients diagnosed dementia,58 a highly vulnerable group of HD patients.59 Consequences of cognitive impairment can also extend beyond a patients’ time on dialysis; among KT recipients, pre-transplant cognitive impairment was associated with higher all-cause graft loss post-KT.60

Interventions to Preserve Cognitive Function in Community-Dwelling Older Adults

Exercise training (ET), is an effective non-pharmacological intervention to preserve global cognitive function,61–63 with the greatest observed impact on executive function in community-dwelling older adults.64–69 Even prior to improving physical function and strength,70 ET in older adults improves executive function69 through increased: 1) cerebral blood flow;71,72 2) brain volume in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus;73–75 3) brain-derived neurotrophic factor;76–80 and 4) engagement of neural structures. ET reduces inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IL-6, resulting in improved brain plasticity and executive function.77,81 Even a single ET session changes neurophysiology and executive function.82–84 ET has a stronger impact on cognitive function and cortical thickness than it does on aerobic fitness.63

Cognitive training (CT)62,85,86 is another promising non-pharmacological intervention used to slow decline in executive function in otherwise healthy older adults. CT prevents age-related declines in key areas of cognitive function, particularly in executive function, including abstraction, working memory, verbal reasoning, and inhibition33,34,87–93 by improving the neural structures that mediate executive function.94–96 Multi-domain approaches to CT, rather than memory training alone, have been associated with broad and lasting gains in healthy older adults91,97,98 and benefits of CT are observable up to 10 years post-training.89

CT and ET are among the few effective non-pharmacological interventions to impact executive function in community-dwelling older adults. Combined CT and ET over 3 months improves executive function70,76,90,99 and is more effective than either CT or ET alone in older adults.76,94 Combined CT and ET enhances synaptic connections between brain cells and improves brain plasticity.100,101

Exercise Interventions in Patients Undergoing HD

Over the past 30 years, there have been several RCTs of exercise in ESKD demonstrating ET effectively improves physical function,102–104 and impacts treatment-related symptoms,105 dialysis efficacy,106 inflammation,103 bone mineral density,103,107 quality of life,108 peak oxygen consumption,109,110 anxiety,111 and exercise capacity.112,113 Compliance and adherence to ET interventions are typically highest when the intervention is delivered during the dialysis session, and there is a general consensus that intradialytic ET is safe.114,115

Exercise as an Intervention to Preserve Cognitive Function in Patients Undergoing Dialysis

Several studies have demonstrated the impact of various forms of ET as an effective intervention for preserving cognitive function in patients undergoing dialysis (Table 1). The Exercise Introduction to Enhance Performance in Dialysis (EXCITE) trial, for example, was a 6-month randomized, multicenter trial aimed at testing whether a home-based, personalized exercise program, including 6-min walking distance and 5-time sit-to-stand testing managed by dialysis staff, would improve functional status in adult patients of all ages on dialysis. The study demonstrated that the self-reported cognitive function and quality of social interaction component scores of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form (KDQOL-SF) improved dramatically in the exercise arm compared with the control arm.116 In subsequent analyses of the EXCITE trial that assessed the effect and tolerance of the program on older dialysis patients (aged 65 years and older) specifically, the intervention arm demonstrated preserved self-reported cognitive function overtime (using the KDQOL), while the control arm, on average, experienced declines in self-reported cognitive function.117

Table 1. Summary of studies examining non-pharmacologic interventions to preserve cognitive function in patients with end-stage kidney disease undergoing dialysis.

3MS= Modified Mini-Mental State Exam for global cognitive function; CT=cognitive training; ET=exercise training; HD= hemodialysis; KDQOL-SF= Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form questionnaire with cognitive function subcomponents; MMSE= Mini-Mental State Exam; NA= not available; SC=standard of care; TMTA and TMTB = Trails Making Tests Parts A and B for processing speed; TMTB – TMTA = Trail Making Test B minus Trails Making Test A for executive function.

| Reference | Population characteristics | Intervention Description | Measures of Cognition | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baggetta et al. 2018117 | Older HD & PD patients aged 65+ years from the Exercise Introduction to Enhance Performance in Dialysis (EXCITE) trial (n=115, mean age=NA) | Home-based, personalized exercise program: 6-min walking distance & 5-time sit-to-stand testing (Duration of exposure: 6 months) | KDQOL-SF | Self-reported cognitive function declined in the control arm (P = 0.04) and remained stable in the active arm (P = 0.78) |

| Manfredini et al. 2017116 | Adult dialysis patients in the Exercise Introduction to Enhance Performance in Dialysis (EXCITE) trial (n=296, mean age=NA) | Home-based, personalized exercise program: 6-min walking distance & 5-time sit-to-stand testing (Duration of exposure: 6 months) | KDQOL-SF | Walking exercise (intervention) vs. normal activity (controls) experienced improvements in self-reported cognitive function (P=0.04) and quality of social interaction (P=0.01) |

| McAdams-DeMarco et al. 2018118 | Adult HD patients of all ages participating in a pilot randomized controlled trial (n=20, mean age=50.8) | Intradialytic CT (tablet-based brain games), ET (foot peddlers), or standard of care (SC) (Duration of exposure: 3 months) | 3MS TMTA TMTB | Patients with SC experienced psychomotor speed and executive function decline by 3 months; this decline was not seen in both intervention arms (CT or ET, all P>0.05). |

| Stringuetta et al. 201872 | Adult HD patients of all ages participating in pilot randomized controlled trial (n=30, mean age=NA) | Intradialytic ET (cycling) (Duration of exposure: 4 months) | MMSE Transcranial Doppler | Patients with ET improved in cognitive function (P=0.001) and basilar maximum blood flow velocity (P=0.029) compared to control group. ET group also had greater proportion of arteries with increased flow velocity (P=0.038). |

Most recently, two pilot studies assessed the impact of different types of intradialytic exercise on cognitive function.72,118 One pilot randomized controlled trail of 30 adult HD patients aged 18 years and older assessed the impact of 4 months of intradialytic cycling for aerobic exercise on cerebral blood flow and cognitive function. The study found that the ET group (N=15) demonstrated improvement in cognitive function and basilar maximum blood flow velocity compared to a control group (N=15), as well as a greater proportion of arteries with increased flow velocity.72

Another pilot randomized controlled trial of 20 HD patients of all ages assessed the impact of 3 months of intradialytic CT (tablet-based brain games) (N=7), ET (foot peddlers) (N= 6), or standard of care (SC) (N=7) on measured cognitive function using the 3MS and TMTA/B.118 Patients with SC experienced decline in psychomotor speed and executive function by 3 months of follow-up; this decline was not seen among those with CT or ET. This pilot trial is being expanded to a 2-by-2 factorial RCT to test whether there is a synergistic effect of combined CT and ET (Clinicaltrials.gov # NCT03616535).

FUTURE RESEARCH

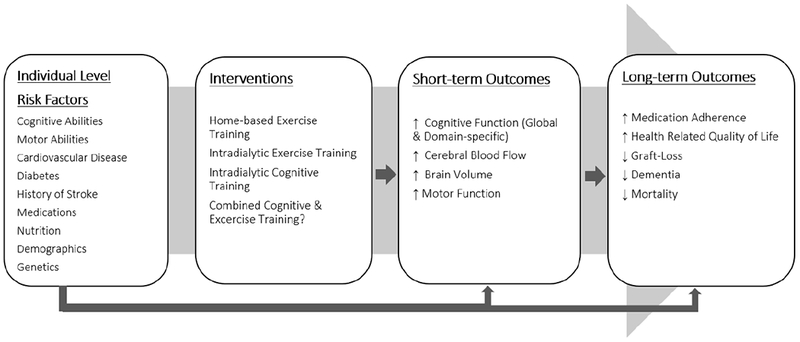

The field has only begun to scratch the surface on short-term impacts of ET, as well as CT, on cognitive outcomes in patients with ESKD. More studies are needed to explore those and other strategies dedicated to preserving cognitive function in KT candidates and recipients. Questions also remain as to whether these non-pharmacologic training strategies can extend the benefits to impact cognitive function in such a way that translates to improvements in activities of daily living and long-term outcomes such as dementia progression and survival (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework of Non-pharmacologic Interventions on Short- and Long-term Outcomes in Patients with End-Stage Kidney Disease.

Black arrows represent impact.

It is encouraging that these interventions can indeed have such a profound effect on health and quality of life, as was demonstrated in the Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly (ACTIVE) trial, an ongoing multi-center trial of healthy community-dwelling older adults followed for 20+ years.89,93,119 The likelihood of success among patients with ESKD may be especially hopeful given the high burden of cognitive impairment, and therefore, greater room for improvement in the face of these interventions; cognitive screening as part of a comprehensive geriatric assessments may help identify those ESKD patients who may benefit most from ET and/or CT.120,121

CONCLUSIONS

Among patients with ESKD, cognitive impairment is common across multiple domains, with the greatest deterioration in executive function, a key domain that often declines with onset of vascular dementia. Transition to dialysis and maintenance dialysis often catalyzes the decline in cognitive function due to retention of uremic toxins, recurrent cerebral ischemia, and high burden of inactivity during dialysis sessions, which may in turn lead to long-term adverse consequences, such as dementia and mortality. Home-based and intradialytic ET, as well as CT, are non-pharmacologic interventions that successfully preserve cognitive function in patients with ESKD. Despite short-term benefits on cognitive function, further research is needed to better understand the long-term consequences of exercise interventions, and whether those benefits may extend to health and quality of life domains in patients undergoing dialysis and KT recipients.

BOX 1. PRACTICAL TIPS FOR NEPHROLOGISTS.

Once a patient is identified as having cognitive impairment, clinicians should consider exercise and cognitive training, as these remain the two most promising interventions to preserve and improve cognitive function in patients with end stage kidney disease (ESKD).

Clinicians should consider using global cognitive assessment tools to screen patients with ESKD at least once every 6 months.

The Modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MS) is a common brief screening tool used to assess cognitive impairment and measure global cognitive function.

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is increasingly being recognized as a better tool as it is more sensitive to capturing ESKD patients with mild cognitive impairment.

BOX 2. AREAS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH.

Future randomized controlled trials should consider exploring the effect of exercise training programs, and potentially cognitive training programs, as non-pharmacologic interventions for preserving cognitive function and potentially improving long-term health and quality of life outcomes in end-stage kidney disease.

Future trials should inform the development of novel interventions to preserve cognitive function for kidney transplant recipients.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

Dr. McAdams-DeMarco was funded by the NIH: K01AG043501, R01AG055781, and R01DK114074.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System, 2016 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases;2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McAdams-DeMarco MA, James N, Salter ML, Walston J, Segev DL. Trends in Kidney Transplant Outcomes in Older Adults Running Header: Kidney Transplant Outcomes in Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014;62(12):2235–2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu NM, Gross AL, Shaffer AA, et al. Frailty and Cognitive Change Among Kidney Transplant Recipients—Failure to Recover to Baseline Levels. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2018;in press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Tan J, Salter ML, et al. Frailty and Cognitive Function in Incident Hemodialysis Patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(12):2181–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurella Tamura M, Larive B, Unruh ML, et al. Prevalence and correlates of cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients: the Frequent Hemodialysis Network trials. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2010;5(8):1429–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta A, Thomas TS, Klein JA, et al. Discrepancies between Perceived and Measured Cognition in Kidney Transplant Recipients: Implications for Clinical Management. Nephron. 2018;138(1):22–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teng E, Chui H. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48(8):314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hill GB, Hébert R. Community screening for dementia: The Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) and modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MS) compared. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1997;50(4):377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurella M, Luan J, Yaffe K, Chertow GM. Validation of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL) Cognitive Function subscale. Kidney International. 2004;66(6):2361–2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drew DA, Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, et al. Cognitive Decline and Its Risk Factors in Prevalent Hemodialysis Patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurella Tamura M, Vittinghoff E, Hsu CY, et al. Loss of executive function after dialysis initiation in adults with chronic kidney disease. Kidney international. 2017;91(4):948–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray AM, Tupper DE, Knopman DS, et al. Cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients is common. Neurology. 2006;67(2):216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Lone E, Connors M, Masson P, et al. Cognition in People With End-Stage Kidney Disease Treated With Hemodialysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(6):925–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones TG, Schinka JA, Vanderploeg RD, Small BJ, Graves AB, Mortimer JA. 3MS normative data for the elderly. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2002;17(2):171–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurella Tamura M, Wadley V, Yaffe K, et al. Kidney function and cognitive impairment in US adults: the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(2):227–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchman AS, Tanne D, Boyle PA, Shah RC, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. Kidney function is associated with the rate of cognitive decline in the elderly. Neurology. 2009;73(12):920–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elias MF, Elias PK, Seliger SL, Narsipur SS, Dore GA, Robbins MA. Chronic kidney disease, creatinine and cognitive functioning. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(8):2446–2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harciarek M, Williamson JB, Biedunkiewicz B, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Debska-Slizien A, Rutkowski B. Risk factors for selective cognitive decline in dialyzed patients with end-stage renal disease: evidence from verbal fluency analysis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2012;18(1):162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altmann P, Barnett ME, Finn WF, Group SPDLCS. Cognitive function in Stage 5 chronic kidney disease patients on hemodialysis: no adverse effects of lanthanum carbonate compared with standard phosphate-binder therapy. Kidney international. 2007;71(3):252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang YH, Yang ZK, Wang JW, et al. Cognitive Changes in Peritoneal Dialysis Patients: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2018;72(5):691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song MK, Paul S, Ward SE, Gilet CA, Hladik GA. One-Year Linear Trajectories of Symptoms, Physical Functioning, Cognitive Functioning, Emotional Well-being, and Spiritual Well-being Among Patients Receiving Dialysis. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2018;72(2):198–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray AM. Cognitive impairment in the aging dialysis and chronic kidney disease populations: an occult burden. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2008;15(2):123–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sehgal AR, Grey SF, DeOreo PB, Whitehouse PJ. Prevalence, recognition, and implications of mental impairment among hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30(1):41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neumann D, Mau W, Wienke A, Girndt M. Peritoneal dialysis is associated with better cognitive function than hemodialysis over a one-year course. Kidney international. 2018;93(2):430–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harhay MN, Xie D, Zhang X, et al. Cognitive Impairment in Non-Dialysis-Dependent CKD and the Transition to Dialysis: Findings From the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2018;72(4):499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta A, Mahnken JD, Johnson DK, et al. Prevalence and correlates of cognitive impairment in kidney transplant recipients. BMC nephrology. 2017;18(1):158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joshee P, Wood AG, Wood ER, Grunfeld EA. Meta-analysis of cognitive functioning in patients following kidney transplantation. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2017:gfx240-gfx240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griva K, Thompson D, Jayasena D, Davenport A, Harrison M, Newman SP. Cognitive functioning pre- to post-kidney transplantation--a prospective study. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2006;21(11):3275–3282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radic J, Ljutic D, Radic M, Kovacic V, Dodig-Curkovic K, Sain M. Kidney transplantation improves cognitive and psychomotor functions in adult hemodialysis patients. American journal of nephrology. 2011;34(5):399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kramer L, Madl C, Stockenhuber F, et al. Beneficial effect of renal transplantation on cognitive brain function. Kidney international. 1996;49(3):833–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dixon BS, VanBuren JM, Rodrigue JR, et al. Cognitive changes associated with switching to frequent nocturnal hemodialysis or renal transplantation. BMC nephrology. 2016;17:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harciarek M, Biedunkiewicz B, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Debska-Slizien A, Rutkowski B. Continuous cognitive improvement 1 year following successful kidney transplant. Kidney international. 2011;79(12):1353–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levine B, Stuss DT, Winocur G, et al. Cognitive rehabilitation in the elderly: effects on strategic behavior in relation to goal management. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13(1):143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahncke HW, Connor BB, Appelman J, et al. Memory enhancement in healthy older adults using a brain plasticity-based training program: a randomized, controlled study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(33):12523–12528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cepeda NJ, Kramer AF, Gonzalez de Sather JC. Changes in executive control across the life span: examination of task-switching performance. Dev Psychol. 2001;37(5):715–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griva K, Stygall J, Hankins M, Davenport A, Harrison M, Newman SP. Cognitive impairment and 7-year mortality in dialysis patients. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2010;56(4):693–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tombaugh TN. Trail Making Test A and B: Normative data stratified by age and education. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2004;19(2):203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sánchez-Fernández MDM, Reyes Del Paso GA, Gil-Cunquero JM, Fernández-Serrano MJ. Executive function in end-stage renal disease: Acute effects of hemodialysis and associations with clinical factors. PloS one. 2018;13(9):e0203424–e0203424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurella M, Chertow GM, Luan J, Yaffe K. Cognitive impairment in chronic kidney disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(11):1863–1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pereira AA, Weiner DE, Scott T, Sarnak MJ. Cognitive function in dialysis patients. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2005;45(3):448–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarnak MJ, Tighiouart H, Scott TM, et al. Frequency of and risk factors for poor cognitive performance in hemodialysis patients. Neurology. 2013;80(5):471–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim ED, Meoni LA, Jaar BG, et al. Association of Arterial Stiffness and Central Pressure With Cognitive Function in Incident Hemodialysis Patients: The PACE Study. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2(6):1149–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drew DA, Bhadelia R, Tighiouart H, et al. Anatomic brain disease in hemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(2):271–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Zwieten A, Wong G, Ruospo M, et al. Prevalence and patterns of cognitive impairment in adult hemodialysis patients: the COGNITIVE-HD study. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2018;33(7):1197–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurella Tamura M, Chertow GM, Depner TA, et al. Metabolic Profiling of Impaired Cognitive Function in Patients Receiving Dialysis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2016;27(12):3780–3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacEwen C, Sutherland S, Daly J, Pugh C, Tarassenko L. Relationship between Hypotension and Cerebral Ischemia during Hemodialysis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2017;28(8):2511–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warsame F, Ying H, Haugen CE, et al. Intradialytic Activities and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Hemodialysis Patients. American journal of nephrology. 2018;48(3):181–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kallenberg MH, Kleinveld HA, Dekker FW, et al. Functional and Cognitive Impairment, Frailty, and Adverse Health Outcomes in Older Patients Reaching ESRD-A Systematic Review. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2016;11(9):1624–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Desmond DW. The neuropsychology of vascular cognitive impairment: is there a specific cognitive deficit? Journal of the neurological sciences. 2004;226(1-2):3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hachinski V, Iadecola C, Petersen RC, et al. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Canadian Stroke Network vascular cognitive impairment harmonization standards. Stroke. 2006;37(9):2220–2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Albert MS, Moss MB, Tanzi R, Jones K. Preclinical prediction of AD using neuropsychological tests. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2001;7(5):631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kray J, Lindenberger U. Adult age differences in task switching. Psychol Aging. 2000;15(1):126–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Daubresse M, Bae S, Gross AL, Carlson MC, Segev DL. Dementia, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Mortality after Hemodialysis Initiation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(9):1339–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Bae S, Chu N, et al. Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease among Older Kidney Transplant Recipients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bassuk SS, Wypij D, Berkman LF. Cognitive impairment and mortality in the community-dwelling elderly. American journal of epidemiology. 2000;151(7):676–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lavery LL, Dodge HH, Snitz B, Ganguli M. Cognitive decline and mortality in a community-based cohort: the Monongahela Valley Independent Elders Survey. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(1):94–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Angermann S, Schier J, Baumann M, et al. Cognitive Impairment is Associated with Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2018;66(4):1529–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Drew DA, Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, et al. Cognitive function and all-cause mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(2):303–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kurella M, Mapes DL, Port FK, Chertow GM. Correlates and outcomes of dementia among dialysis patients: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(9):2543–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thomas AG, Ruck JM, Shaffer AA, et al. Kidney Transplant Outcomes in Recipients with Cognitive Impairment: A National Registry and Prospective Cohort Study. Transplantation. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lautenschlager NT, Cox KL, Flicker L, et al. Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(9):1027–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chapman SB, Aslan S, Spence JS, et al. Distinct Brain and Behavioral Benefits from Cognitive vs. Physical Training: A Randomized Trial in Aging Adults. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2016;10:338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jonasson LS, Nyberg L, Kramer AF, Lundquist A, Riklund K, Boraxbekk CJ. Aerobic Exercise Intervention, Cognitive Performance, and Brain Structure: Results from the Physical Influences on Brain in Aging (PHIBRA) Study. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2016;8:336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anderson-Hanley C, Nimon JP, Westen SC. Cognitive health benefits of strengthening exercise for community-dwelling older adults. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 2010;32(9):996–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Best JR, Nagamatsu LS, Liu-Ambrose T. Improvements to executive function during exercise training predict maintenance of physical activity over the following year. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2014;8:353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Colcombe S, Kramer AF. Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Sci. 2003;14(2):125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Etnier JL, Chang YK. The effect of physical activity on executive function: a brief commentary on definitions, measurement issues, and the current state of the literature. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2009;31(4):469–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hillman CH, Belopolsky AV, Snook EM, Kramer AF, McAuley E. Physical activity and executive control: implications for increased cognitive health during older adulthood. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2004;75(2):176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Erickson KI, Kramer AF. Aerobic exercise effects on cognitive and neural plasticity in older adults. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(1):22–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barcelos N, Shah N, Cohen K, et al. Aerobic and Cognitive Exercise (ACE) Pilot Study for Older Adults: Executive Function Improves with Cognitive Challenge While Exergaming. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2015;21(10):768–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guiney H, Lucas SJ, Cotter JD, Machado L. Evidence cerebral blood-flow regulation mediates exercise-cognition links in healthy young adults. Neuropsychology. 2015;29(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stringuetta Belik F, Oliveira ESVR, Braga GP, et al. Influence of Intradialytic Aerobic Training in Cerebral Blood Flow and Cognitive Function in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Nephron. 2018;140(1):9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Colcombe SJ, Erickson KI, Scalf PE, et al. Aerobic exercise training increases brain volume in aging humans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(11):1166–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, et al. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(7):3017–3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Voss MW, Prakash RS, Erickson KI, et al. Plasticity of brain networks in a randomized intervention trial of exercise training in older adults. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2010;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Anderson-Hanley C, Arciero PJ, Brickman AM, et al. Exergaming and older adult cognition: a cluster randomized clinical trial. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(2):109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nascimento CM, Pereira JR, Pires de Andrade L, et al. Physical exercise improves peripheral BDNF levels and cognitive functions in mild cognitive impairment elderly with different bdnf Val66Met genotypes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43(1):81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hotting K, Roder B. Beneficial effects of physical exercise on neuroplasticity and cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(9 Pt B):2243–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Knaepen K, Goekint M, Heyman EM, Meeusen R. Neuroplasticity - exercise-induced response of peripheral brain-derived neurotrophic factor: a systematic review of experimental studies in human subjects. Sports Med. 2010;40(9):765–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leckie RL, Oberlin LE, Voss MW, et al. BDNF mediates improvements in executive function following a 1-year exercise intervention. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2014;8:985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Loprinzi PD, Herod SM, Cardinal BJ, Noakes TD. Physical activity and the brain: a review of this dynamic, bi-directional relationship. Brain Res. 2013;1539:95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.O’Leary KC, Pontifex MB, Scudder MR, Brown ML, Hillman CH. The effects of single bouts of aerobic exercise, exergaming, and videogame play on cognitive control. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;122(8):1518–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Roig M, Skriver K, Lundbye-Jensen J, Kiens B, Nielsen JB. A single bout of exercise improves motor memory. PloS one. 2012;7(9):e44594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Statton MA, Encarnacion M, Celnik P, Bastian AJ. A Single Bout of Moderate Aerobic Exercise Improves Motor Skill Acquisition. PloS one. 2015;10(10):e0141393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gregory SM, Parker B, Thompson PD. Physical activity, cognitive function, and brain health: what is the role of exercise training in the prevention of dementia? Brain sciences. 2012;2(4):684–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ballesteros S, Prieto A, Mayas J, et al. Brain training with non-action video games enhances aspects of cognition in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2014;6:277–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Anand R, Chapman SB, Rackley A, Keebler M, Zientz J, Hart J Jr. Gist reasoning training in cognitively normal seniors. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2011;26(9):961–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Karbach J, Kray J. How useful is executive control training? Age differences in near and far transfer of task-switching training. Dev Sci. 2009;12(6):978–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rebok GW, Ball K, Guey LT, et al. Ten-year effects of the advanced cognitive training for independent and vital elderly cognitive training trial on cognition and everyday functioning in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014;62(1):16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shatil E Does combined cognitive training and physical activity training enhance cognitive abilities more than either alone? A four-condition randomized controlled trial among healthy older adults. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2013;5:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Strenziok M, Parasuraman R, Clarke E, Cisler DS, Thompson JC, Greenwood PM. Neurocognitive enhancement in older adults: comparison of three cognitive training tasks to test a hypothesis of training transfer in brain connectivity. Neuroimage. 2014;85 Pt 3:1027–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tagliabue CF, Guzzetti S, Gualco G, et al. A group study on the effects of a short multi-domain cognitive training in healthy elderly Italian people. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wolinsky FD, Unverzagt FW, Smith DM, Jones R, Stoddard A, Tennstedt SL. The ACTIVE cognitive training trial and health-related quality of life: protection that lasts for 5 years. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(12):1324–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fabre C, Chamari K, Mucci P, Masse-Biron J, Prefaut C. Improvement of cognitive function by mental and/or individualized aerobic training in healthy elderly subjects. Int J Sports Med. 2002;23(6):415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Maclin EL, Mathewson KE, Low KA, et al. Learning to multitask: effects of video game practice on electrophysiological indices of attention and resource allocation. Psychophysiology. 2011;48(9):1173–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mathewson KE, Basak C, Maclin EL, et al. Different slopes for different folks: alpha and delta EEG power predict subsequent video game learning rate and improvements in cognitive control tasks. Psychophysiology. 2012;49(12):1558–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chapman SB, Mudar RA. Enhancement of cognitive and neural functions through complex reasoning training: evidence from normal and clinical populations. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.McDaniel MA, Binder EF, Bugg JM, et al. Effects of cognitive training with and without aerobic exercise on cognitively demanding everyday activities. Psychol Aging. 2014;29(3):717–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maillot P, Perrot A, Hartley A. Effects of interactive physical-activity video-game training on physical and cognitive function in older adults. Psychol Aging. 2012;27(3):589–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bennett EL, Diamond MC, Krech D, Rosenzweig MR. Chemical and Anatomical Plasticity Brain. Science. 1964;146(3644):610–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Spatz HC. Hebb’s concept of synaptic plasticity and neuronal cell assemblies. Behav Brain Res. 1996;78(1):3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cheema BS, Singh MA. Exercise training in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis: a systematic review of clinical trials. American journal of nephrology. 2005;25(4):352–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liao MT, Liu WC, Lin FH, et al. Intradialytic aerobic cycling exercise alleviates inflammation and improves endothelial progenitor cell count and bone density in hemodialysis patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(27):e4134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bennett PN, Fraser S, Barnard R, et al. Effects of an intradialytic resistance training programme on physical function: a prospective stepped-wedge randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Giannaki CD, Hadjigeorgiou GM, Karatzaferi C, et al. A single-blind randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of 6 months of progressive aerobic exercise training in patients with uraemic restless legs syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(11):2834–2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Parsons TL, Toffelmire EB, King-VanVlack CE. The effect of an exercise program during hemodialysis on dialysis efficacy, blood pressure and quality of life in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients. Clin Nephrol. 2004;61(4):261–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Marinho SM, C M, Jesm B, et al. Exercise training alters the bone mineral density of hemodialysis patients. J Strength Cond Res. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kolewaski CD, Mullally MC, Parsons TL, Paterson ML, Toffelmire EB, King-VanVlack CE. Quality of life and exercise rehabilitation in end stage renal disease. CANNT J. 2005;15(4):22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Painter PL, Nelson-Worel JN, Hill MM, et al. Effects of exercise training during hemodialysis. Nephron. 1986;43(2):87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Painter P, Moore G, Carlson L, et al. Effects of exercise training plus normalization of hematocrit on exercise capacity and health-related quality of life. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2):257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Moug SJ, Grant S, Creed G, Boulton Jones M. Exercise during haemodialysis: West of Scotland pilot study. Scottish medical journal. 2004;49(1):14–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.DePaul V, Moreland J, Eager T, Clase CM. The effectiveness of aerobic and muscle strength training in patients receiving hemodialysis and EPO: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40(6):1219–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kouidi EJ, Grekas DM, Deligiannis AP. Effects of exercise training on noninvasive cardiac measures in patients undergoing long-term hemodialysis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54(3):511–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Johansen KL. Exercise in the end-stage renal disease population. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(6):1845–1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sheng K, Zhang P, Chen L, Cheng J, Wu C, Chen J. Intradialytic exercise in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of nephrology. 2014;40(5):478–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Manfredini F, Mallamaci F, D’Arrigo G, et al. Exercise in Patients on Dialysis: A Multicenter, Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2017;28(4):1259–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Baggetta R, D’Arrigo G, Torino C, et al. Effect of a home based, low intensity, physical exercise program in older adults dialysis patients: a secondary analysis of the EXCITE trial. BMC geriatrics. 2018;18(1):248–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Konel J, Warsame F, et al. Intradialytic cognitive and exercise training may preserve cognitive function. Kidney international reports. 2018;3(1):81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ball K, Berch DB, Helmers KF, et al. Effects of cognitive training interventions with older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2002;288(18):2271–2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hall RK, Haines C, Gorbatkin SM, et al. Incorporating Geriatric Assessment into a Nephrology Clinic: Preliminary Data from Two Models of Care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(10):2154–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hall RK, McAdams-DeMarco MA. Breaking the cycle of functional decline in older dialysis patients. Seminars in dialysis. 2018;31(5):462–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]