Abstract

Objective

To estimate dementia's incremental cost to the traditional Medicare program.

Data Sources

Health and Retirement Study (HRS) survey‐linked Medicare part A and B claims from 1991 to 2012.

Study Design

We compared Medicare expenditures for 60 months following a claims‐based dementia diagnosis to those for a randomly selected, matched comparison group.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

We used a cost estimator that accounts for differential survival between individuals with and without dementia and decomposes incremental costs into survival and cost intensity components.

Principal Findings

Dementia's five‐year incremental cost to the traditional Medicare program is approximately $15 700 per patient, nearly half of which is incurred in the first year after diagnosis. Shorter survival with dementia mitigates the incremental cost by about $2650. Increased costs for individuals with dementia were driven by more intensive use of Medicare part A covered services. The incremental cost of dementia was about $7850 higher for females than for males because of sex‐specific differential mortality associated with dementia.

Conclusions

Dementia's cost to the traditional Medicare program is significant. Interventions that target early identification of dementia and preventable inpatient and post‐acute care services could produce substantial savings.

Keywords: aging, Alzheimer's disease, dementia, health care costs, Medicare

1. INTRODUCTION

An estimated four to five million older adults in the United States are living with dementia,1 a chronic, progressive condition characterized by cognitive decline of sufficient severity to interfere with a person's ability to carry out daily activities.2 Despite recent evidence that prevalence rates of dementia may be declining in high‐income countries,1, 3 population forecasts indicate significant growth in the absolute number of adults in the United States living with dementia as the population ages and mortality from other diseases declines.4

Understanding the magnitude of the direct medical care costs attributable to dementia is important for public and private decision makers, but estimating these costs has been difficult. Even when focused on the direct costs to the traditional Medicare program, estimates have ranged widely, with differences driven by the time period and population studied, the definition used to identify dementia, and the study design and analytic techniques employed. For example, the handful of studies employing a cross‐sectional design, comparing Medicare expenditures over one year for people with a dementia diagnosis and people without, reported annual incremental costs ranging from $3019 to $10 598 per person, in 2017 dollars.5, 6, 7, 8 In the study producing the highest estimate, Bynum et al5 used a random five percent sample of Medicare beneficiaries and identified people with dementia using claims‐based diagnosis codes. Using survey responses to cognitive and physical functioning questions in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), Hurd et al6 compared Medicare expenditures for people with varying probabilities of dementia, resulting in the lowest cost estimate. Due to their cross‐sectional design, these studies examined prevalent cases of dementia. Thus, annual cost estimates reflect averages for people in varying stages of disease progression, even though incremental costs may differ over the course of the disease. If the case mix of disease changes in the population, these estimates will no longer hold.

Studies examining costs over time have demonstrated large variations in the incremental cost associated with dementia depending on the time since diagnosis and the proximity to death. For example, Lin et al9 examined costs around the time of diagnosis among a five percent sample of Medicare beneficiaries and found a substantial incremental cost of $18 423 in the first year after diagnosis. The incremental cost markedly declined by the second year to $7561.9 In contrast, two studies that limited their study samples to decedents and examined Medicare expenditures in the 5 years before death for older adults with dementia and without found similar 5‐year costs between the two groups overall.10, 11 Similar to Lin et al (2016), however, one of these studies determined that time since diagnosis significantly influenced the incremental cost estimates.9, 11 When the first claims‐based diagnosis of dementia occurred in the last year of life, 5‐year costs were significantly higher in the dementia group, with an estimated incremental cost of $20 933.11

Finally, two longitudinal studies estimated Medicare expenditures over the entire course of the disease, with widely varying results.12, 13 In the first, Ayyagari, Salm, and Sloan (2007) used data from two waves of the National Long‐Term Care Survey (NLTCS) and linked Medicare claims to estimate survival curves for individuals with and without dementia as well as cost models for each group. Accounting for the annual mortality risk of dementia, they estimated an expected increase in Medicare spending of $2214 over the lifetime for a 65‐year‐old who may be diagnosed with dementia before death.12 However, the study sample was restricted to older adults with functional limitations, potentially biasing costs associated with dementia. Additionally, the analysis did not account for a different pattern of costs at the end of life. Yang et al (2012) used data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) to generate inputs for a cohort‐based simulation study. The simulation accounted for the probability of a dementia diagnosis by age and Medicare costs conditional on dementia status, estimating an average lifetime incremental cost of $15 208.13 However, the cost models neglected to account for time since diagnosis.13

Our study will address several limitations in the existing literature on Medicare costs attributable to dementia. Using longitudinal data from a large, population‐based dataset linked to Medicare claims, we estimate the incremental cost of dementia to the traditional Medicare program (parts A and B) for the first five years after a claims‐based diagnosis is recorded, both for older adults overall and by sex. To accomplish this, we employ the Basu and Manning estimator (2010), which is designed to estimate costs under censoring.14 This estimator also accounts for differential survival between individuals with and without dementia, separating the marginal effect on costs into the part brought about by dementia influencing length of survival and the part brought by dementia influencing intensity of health service utilization. Our study, therefore, provides the first longitudinal analysis of the cost of dementia that simultaneously considers the relationship between dementia attributable mortality and costs within a population‐based sample of older adults.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and data sources

We identify a retrospective cohort of older adults with dementia who participated in the HRS, a longitudinal study of aging that gathers information on physical and mental health, health services utilization, and financial resources of older Americans. The HRS provides detailed information from a representative national sample of 20 000 adults older than 50 every 2 years. For our analysis, we linked HRS survey responses to Medicare part A and B claims from 1991 to 2012 for the subset of HRS participants who consented to review of their Medicare records (over 80 percent of Medicare‐eligible participants) and had fee‐for‐service (FFS) coverage during this time period. We examined Medicare expenditures for the 12 months prior and up to 60 months following a diagnosis of dementia as recorded on claims submitted for reimbursement. We randomly selected a comparison group of HRS participants matching on sex, birth year, and HRS entry year. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington, the HRS Restricted Data Applications Processing Center, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Privacy Board.

2.2. Study population

We used ICD‐9‐CM diagnostic codes from Medicare claims to identify participants with dementia. To qualify as a dementia case, individuals were required to be enrolled in Medicare parts A and B FFS coverage for at least 12 months before and 1 month after receipt of one of the following diagnosis codes in an inpatient, skilled nursing facility, home health, hospital outpatient, or carrier claim: 331.x, 290.x, 294.x, or 797 (specific codes and descriptions provided in Appendix S1).9, 15 We excluded individuals insured through the Medicare Advantage (MA) program because MA plans are not required to provide complete cost and utilization data to CMS. We defined the diagnosis date for dementia cases as the date of the first qualifying diagnosis code.

Our comparison group was selected from among all HRS participants with Medicare enrollment information for the study period. After matching dementia cases to all possible comparators on sex, birth year, and HRS survey entry year, up to five controls were randomly selected for each case. Inclusion criteria for the controls were enrollment in Medicare parts A and B FFS coverage for the 12 months before and 1 month after the diagnosis date of their matched case. Additionally, controls had no dementia diagnosis themselves or for a household member prior to or for the 72 months following the diagnosis date of their matched dementia case. This last criterion was applied to address the concern that the health and health care costs of these participants may have been indirectly influenced by their household member's dementia diagnosis. Controls were given the diagnosis date of their assigned case to allow for a comparison of equivalent time periods.

2.3. Measures

We measured health care expenditures as the amount Medicare paid for all part A and B claims, including inpatient, skilled nursing facility, institutional outpatient, carrier, home health, durable medical equipment, and hospice services. Expenditures for prescription drugs that are not administered by a physician were not included. Monthly expenditures for the 12 months prior to and 60 months following the diagnosis date were calculated. We adjusted expenditures for inflation using the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index for health care and report all amounts in 2017 dollars.16

2.4. Statistical analysis

To calculate the marginal effect of dementia on Medicare expenditures, we used the estimator described by Basu and Manning14 for estimating costs under censoring. Estimation was done in several steps. First, costs were estimated using a two‐part model; the first part estimated the probability of any costs during each month using a logit model, while the second part estimated the magnitude of costs when costs were greater than zero using a generalized linear model with gamma family and power link of 0.95. This estimation is done in two steps: (a) for months prior to death or censoring and again, (b) for months in which death occurred. All models controlled for age, sex, marital status, level of education, quartile of total expenditures for the 12 months prior to the diagnosis date, and the following comorbid conditions: anemia, arthritis, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and stroke. Additionally, models included time from diagnosis (in months), an interaction term for dementia status and time from diagnosis, indicators for years from diagnosis, and interactions between time from diagnosis and the yearly indicator variables. Inclusion of these time variables allowed for both nonlinearity in the relationship between time and costs, and for the relationship to differ depending on year from diagnosis and year of diagnosis. Finally, an accelerated failure time model based on the lognormal distribution for time was used to estimate each subject's survival function after accounting for censoring. The survival model controlled for the same sociodemographic and health characteristics as the cost models. We estimated marginal effects from each of the above models using the method of recycled predictions, whereby counterfactual predictions for costs without dementia were made by “turning off” the dementia indicator among patients with dementia and predicting their costs. The estimates were then combined according to the following formula:

where X = {D,W}, D is an indicator for dementia and W represents a vector of all other covariates, is the estimated cost for interval j for any individual, is the estimated survivor function, is the estimated hazard function, is the estimated cost in the months of death, and is the estimated cost in months prior to death or censoring. We also partitioned the incremental difference in costs into a portion where survival was held constant between those with and without dementia, producing costs arising entirely due to differences in the intensity of costs, and another portion where the intensity of costs per month was held constant, producing costs arising entirely due to survival differences. Specific formulas for each part of the analysis are given in the Appendix S1. Standard errors were obtained via bootstrapping with 1000 iterations. All analyses were conducted in STATA 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

3. RESULTS

A total of 22 339 HRS participants provided their Medicare identification number, for whom we obtained Medicare enrollment information for the years 1991‐2012. Of these, 5477 participants had a dementia diagnosis code and 4335 met the Medicare enrollment criteria. We were unable to find an adequate match for 325 of the dementia cases because they entered the HRS study at an unusual wave for their birth year or because they were diagnosed with dementia at such an advanced age that there were no comparators available who were unaffected by dementia themselves. Consequently, a final study population of 4010 cases were included in our analysis. Of the 22 339 possible comparators, 10 860 were selected as controls for the analysis, with each dementia case assigned an average of 2.5 controls (range 1‐5).

Almost one‐third (32 percent) of the 14 870 participants included in our cost analysis had censored data prior to the 60 months of follow‐up because participants switched to an MA plan (15 percent) or the 60 months of follow‐up extended beyond 12/31/2012 (17 percent), the final date of our dataset. For our survival model data, 19 percent of our 14 870 participants were censored prior to 60 months due solely to survival beyond 12/31/2012. More complete longitudinal data were available for our survival modeling because deaths were still observed even when a switch to an MA plan occurred.

Sociodemographic and health characteristics of our study sample are reported in Table 1. Participants were 81 years of age, on average, at the time of diagnosis and a little over one‐third were male. These characteristics align with other sources.1, 17 A smaller proportion of participants with a dementia diagnosis were non‐Hispanic white (75.7 vs 80.9), had any college‐level education (26.3 vs 30.4 percent), and had served in the military (20.7 vs 23.0 percent) than participants in the control group. In the one year prior to dementia onset date, participants with a dementia diagnosis suffered from a higher degree of comorbidity than did participants in the control group, with a significantly higher proportion of cases with each chronic condition examined. People with dementia also had significantly higher Medicare expenditures in the 12 months prior to the diagnosis date ($17 116 vs $10 085).

Table 1.

Characteristics of dementia cases and the first matched control

| Participants with dementia diagnosis (n = 4010) | First matched control (n = 4010) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age at diagnosis in years, mean (SD) | 80.9 (7.8) | 80.9 (7.8) | 0.954 |

| Male, % | 37.3 | 37.3 | 1.000 |

| Race, % | |||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 75.7 | 80.9 | <0.001 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 16.2 | 12.2 | |

| Hispanic | 6.7 | 5.3 | |

| Non‐Hispanic other | 1.5 | 1.5 | |

| Marital status at diagnosis, % | |||

| Married | 39.1 | 40.8 | 0.667 |

| Separated/divorced | 7.1 | 6.8 | |

| Widowed | 44.9 | 43.8 | |

| Never married | 3.0 | 3.0 | |

| Unknown marital status | 5.9 | 5.7 | |

| Educational attainment, % | |||

| Less than high school | 41.7 | 35.4 | <0.001 |

| High school graduate | 31.9 | 34.2 | |

| Some college | 14.2 | 17.3 | |

| College and above | 12.1 | 13.1 | |

| Veteran, % | 20.7 | 23.0 | 0.015 |

| Health characteristics at baselinea | |||

| Comorbid conditions, % | |||

| Anemia | 39.2 | 23.0 | <0.001 |

| Arthritis | 36.5 | 27.2 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 14.2 | 9.6 | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 17.1 | 10.3 | <0.001 |

| COPD | 19.7 | 13.1 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 21.3 | 5.9 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 30.6 | 22.4 | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 34.0 | 24.1 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 69.7 | 53.8 | <0.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 47.3 | 37.1 | <0.001 |

| Stroke/TIA | 17.8 | 4.2 | <0.001 |

| Total expenditures, mean (SD) | 17 116 (29 041) | 10 085 (20 152) | <0.001 |

The baseline period was defined as the 12 months prior to the diagnosis date.

Period‐specific absolute and incremental costs for the entire study sample, calculated as outlined above in order to account for comorbidity and other individual characteristics, are shown in Table 2. In the five years following a dementia diagnosis, total Medicare expenditures are estimated to be $71 917 (95% CI: $69 717, $74 219) for participants with a diagnosis of dementia and $56 214 (95% CI: $54 290, $58 132) for these same participants in the absence of dementia, resulting in a five‐year incremental cost of $15 704 (95% CI: $13 431, $18 434). The expenditure difference is driven by greater intensity of health service utilization by participants with dementia; the five‐year incremental cost when holding survival constant is estimated at $18 348 (95% CI: $16 121, $21 001). Survival time, however, is significantly shorter in participants with a dementia diagnosis, thereby mitigating the estimated incremental cost by $2645 (95% CI: −$3938, −$1390) over five years. Notably, 46 percent of the incremental cost is incurred in the first year after diagnosis. Incremental costs decrease as time from diagnosis increases, such that the cost differential in year five is nearly zero. This decline is not just driven by the survival effects, but also the intensity effects.

Table 2.

Period‐specific absolute and incremental costs for the entire study population

| Total costs | Incremental costs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted costs with dementia diagnosisb | Predicted costs without dementiab | Incremental costs if survival held constant | Incremental costs due to changed survival | Total incremental costs | |

| Months 1‐12a | $23 917 (23 078, 24 841) | $16 653 (16 071, 17 300) | $7620 (6655, 8659) | −$356 (−527, −183) | $7264 (6347, 8243) |

| Months 13‐24 | $16 286 (15 701, 16 945) | $12 046 (11 589, 12 559) | $4774 (4218, 5377) | −$533 (−795, −279) | $4241 (3703, 4870) |

| Months 25‐36 | $12 766 (12 257, 13 285) | $10 246 (9812, 10 700) | $3099 (2687, 3579) | −$579 (−859, −304) | $2520 (2053, 3071) |

| Months 37‐48 | $10 273 (9792, 10 829) | $8971 (8541, 9429) | $1885 (1438, 2370) | −$584 (−867, −306) | $1302 (777, 1906) |

| Months 49‐60 | $8675 (8175, 9225) | $8298 (7791, 8789) | $970 (457, 1543) | −$593 (−884, −311) | $377 (−221, 1054) |

| Total | $71 917 (69 717, 74 219) | $56 214 (54 290, 58 132) | $18 348 (16 121, 21 001) | −$2645 (−3938, −1390) | $15 704 (13 431, 18 434) |

Month 1 is the month in which the diagnosis date occurred.

Predicted costs are calculated only among participants with a dementia diagnosis.

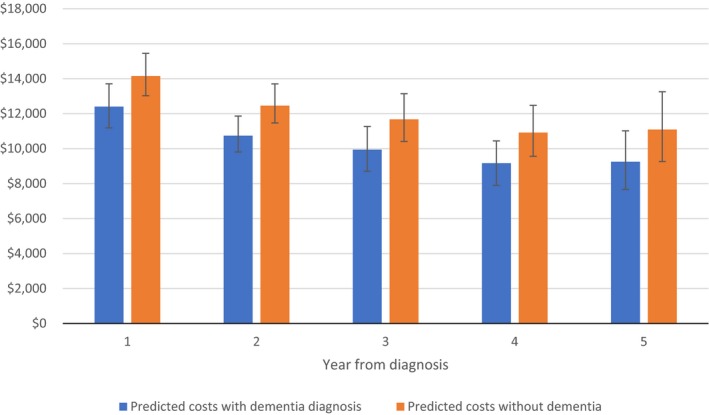

Despite greater intensity of utilization after dementia diagnosis, costs in the month of death indicate lower intensity of health service utilization by participants with dementia at the end of life. Average costs in the month of death for participants with a diagnosis of dementia and predicted costs in the absence of dementia are shown in Figure 1. In all time periods after diagnosis, estimated expenditures in the month of death are lower in the presence of a dementia diagnosis, though confidence intervals overlap in each time period. Irrespective of dementia status, estimated costs in the month of death decline from the first year after diagnosis through the fourth year.

Figure 1.

Average predicted costs in the month of death by year from diagnosis [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Absolute and incremental costs when separately examining Medicare part A and B expenditures are shown in Table 3. The five‐year incremental cost for services covered by part A, including inpatient, skilled nursing, and hospice care, is estimated at $17 717 (95% CI: $15 475, $19 788). Part A costs were significantly higher in the presence of a dementia diagnosis for every year observed, although half of the five‐year incremental cost is incurred in the first year after diagnosis. For 40.8 percent of participants with dementia, initial diagnosis occurred during a hospitalization or stay in a skilled nursing facility. More than one‐third (37.5 percent) also experienced a hospital or skilled nursing facility admission in the six months following their diagnosis, as compared with 18.5 percent of participants in the control group. Part B costs, in contrast, were only significantly higher for participants with a dementia diagnosis in the first year after diagnosis. The five‐year incremental cost for services covered by part B was not significantly different from zero ($65, 95% CI: −$600, $788).

Table 3.

Period‐specific absolute and incremental costs for part A and part B covered services

| Total costs | Incremental costs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted costs with dementia diagnosisb | Predicted costs without dementiab | Incremental costs if survival held constant | Incremental costs due to changed survival | Total incremental costs | |

| Part A costs | |||||

| Months 1‐12a | $20 645 (19 782, 21 505) | $11 678 (11 144, 12 271) | $9203 (8235, 10 107) | −$236 (−354, −114) | $8967 (8005, 9836) |

| Months 13‐24 | $10 900 (10 390, 11 437) | $6839 (6506, 7231) | $4371 (3877, 4819) | −$309 (−469, −150) | $4062 (3600, 4503) |

| Months 25‐36 | $8406 (7931, 8901) | $5846 (5510, 6223) | $2898 (2451, 3296) | −$338 (−518, −163) | $2561 (2115, 2983) |

| Months 37‐48 | $6851 (6353, 7390) | $5353 (5007, 5736) | $1854 (1352, 2345) | −$356 (−541, −177) | $1498 (986, 1980) |

| Months 49‐60 | $5552 (5054, 6034) | $4923 (4551, 5339) | $989 (431, 1520) | −$360 (−550, −173) | $629 (51, 1163) |

| Total | $52 354 (50 526, 54 302) | $34 639 (33 297, 36 113) | $19 315 (17 016, 21 374) | −$1599 (−2417, −781) | $17 717 (15 475, 19 788) |

| Part B costs | |||||

| Months 1‐12a | $6516 (6308, 6739) | $5757 (5561, 5957) | $874 (646, 1082) | −$115 (−172, −55) | $759 (550, 958) |

| Months 13‐24 | $4618 (4451, 4800) | $4398 (4234, 4564) | $405 (263, 546) | −$186 (−278, −90) | $219 (78, 378) |

| Months 25‐36 | $3669 (3521, 3833) | $3767 (3610, 3918) | $107 (−3, 239) | −$205 (−306, −99) | −$98 (−234, 56) |

| Months 37‐48 | $3027 (2882, 3182) | $3348 (3198, 3495) | −$111 (−230, 30) | −$211 (−316, −101) | −$321 (−473, −144) |

| Months 49‐60 | $2594 (2449, 2754) | $3087 (2928, 3233) | −$279 (−419, −120) | −214 (−321, −104) | −$494 (−670, −290) |

| Total | $20 424 (19 758, 21 134) | $20 357 (19 670, 21 067) | $996 (410, 1646) | −$931 (−1395, −451) | $65 (−600, 788) |

Month 1 is the month in which the diagnosis date occurred.

Predicted costs are calculated only among participants with a dementia diagnosis.

Estimated Medicare expenditures were comparable for women and men with a dementia diagnosis at $72 303 (95% CI: $69 508, $75 188) for women and $70 643 (95% CI: $67 304, $74 728) for men. (Table 4) However, differing survival patterns between women and men led to disparate incremental cost estimates. Among women, survival time is not significantly different with a dementia diagnosis. Thus, the estimated incremental cost of $18 284 (95% CI: $15 042, $21 497) over five years solely reflects the greater intensity of health services utilization among women with a dementia diagnosis. Among men, survival time is significantly shorter for individuals with a dementia diagnosis. Consequently, greater intensity of health services utilization ($16 371, 95% CI: $12 354, $20 496) is offset substantially by decreased survival time (−$5937, 95% CI: −$8162, −$3647), resulting in a five‐year incremental cost of $10 434 (95% CI: $6296, $14 636).

Table 4.

Period‐specific absolute and incremental costs for women and men

| Total costs | Incremental costs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted costs with dementia diagnosisb | Predicted costs without dementiab | Incremental costs if survival held constant | Incremental costs due to changed survival | Total incremental costs | |

| Women | |||||

| Months 1‐12a | $23 118 (22 097, 24 115) | $15 644 (14 881, 16 444) | $7575 (6440, 8743) | −$100 (−326, 122) | $7474 (6373, 8596) |

| Months 13‐24 | $16 356 (15 615, 17 126) | $11 575 (10 991, 12 210) | $4933 (4238, 5690) | −$152 (−501, 184) | $4781 (4078, 5487) |

| Months 25‐36 | $13 069 (12 397, 13 755) | $9931 (9377, 10 491) | $3305 (2708, 3895) | −$166 (−544, 201) | $3138 (2479, 3755) |

| Months 37‐48 | $10 622 (9974, 11 236) | $8710 (8220, 9232) | $2080 (1476, 2689) | −$168 (−553, 203) | $1911 (1193, 2601) |

| Months 49‐60 | $9138 (8453, 9852) | $8157 (7561, 8806) | $1153 (439, 1880) | −$173 (−570, 211) | $980 (145, 1776) |

| Total | $72 303 (69 508, 75 188) | $54 017 (51 830, 56 406) | $19 046 (15 930, 22 203) | −$759 (−2502, 926) | $18 284 (15 042, 21 497) |

| Men | |||||

| Months 1‐12a | $25 160 (23 740, 26 728) | $18 540 (17 519, 19 642) | $7445 (5878, 9323) | −$826 (−1156, −507) | $6620 (5125, 8377) |

| Months 13‐24 | $15 942 (14 997, 17 053) | $12 865 (12 098, 13 736) | $4283 (3371, 5293) | −$1206 (−1667, −731) | $3077 (2161, 4075) |

| Months 25‐36 | $12 107 (11 254, 13 012) | $10 806 (10 091, 11 600) | $2600 (1880, 3354) | −$1299 (−1805, −809) | $1300 (459, 2117) |

| Months 37‐48 | $9599 (8723, 10 525) | $9470 (8766, 10 229) | $1438 (642, 2264) | −$1309 (−1815, −805) | $129 (−719, 997) |

| Months 49‐60 | $7835 (6960, 8757) | $8527 (7870, 9294) | $605 (−286, 1512) | −$1297 (−1800, −798) | −$692 (−1691, 311) |

| Total | $70 643 (67 304, 74 728) | $60 208 (57 439, 63 320) | $16 371 (12 354, 20 496) | −$5937 (−8162, −3647) | $10 434 (6296, 14 636) |

Month 1 is the month in which the diagnosis date occurred.

Predicted costs are calculated only among participants with a dementia diagnosis.

4. DISCUSSION

We found that dementia costs traditional Medicare approximately $15 700 in incremental costs in the five years after a dementia diagnosis. Nearly half of the incremental cost occurred in the first year after diagnosis, with the incremental cost decreasing as the time from diagnosis increased. Increased costs for individuals with dementia were wholly driven by more intensive use of Medicare part A covered services, including inpatient, skilled nursing, and hospice care. At the end of life, however, individuals with dementia had consistently lower costs. The incremental cost of dementia was about $7850 higher for females than for males because of different mortality risks associated with dementia for males and females.

Our five‐year incremental cost estimate of $15 700 is consistent with the high end of longitudinal cost estimates in the literature, and very similar to the lifetime estimate reported by Yang et al13 in their simulation study. Our yearly incremental cost estimates confirm and extend findings from prior studies of dementia costs focused around the time of diagnosis.9, 18 As with those prior studies, we found the highest incremental cost in the year after diagnosis with substantially lower costs by the second year. Our results indicate that this downward trend in incremental cost as diagnosis date recedes in the past continues after the second year. Our findings also showed that higher estimated costs in the first two years after diagnosis were preceded by significantly higher unadjusted costs among participants with dementia in the 12 months prior to diagnosis. Studies examining utilization and costs in the period before a dementia diagnosis have reported an increase in most measures of outpatient and inpatient utilization as well as costs beginning in the year prior to diagnosis.9, 19, 20, 21, 22 Higher costs in the prediagnosis period may result from a higher comorbidity burden among individuals with dementia and the concomitant challenges of managing comorbid conditions in the setting of cognitive impairment.23 It may also reflect, at least in part, the distress these individuals and their families express that leads to greater contact with the health care system and eventually to a dementia diagnosis. These results indicate an important opportunity to reduce distress and uncertainty while simultaneously reducing incremental costs through earlier identification of dementia and improved care management.

Our finding that dementia attributable costs are due to greater use of Medicare part A covered services is also in agreement with results from prior studies.5, 9 To the extent that some inpatient and post‐acute care services used after a dementia diagnosis are preventable,5, 24, 25 there is further potential for reducing dementia attributable Medicare costs. Finally, our finding that Medicare costs in the month of death are lower for people with dementia is consistent with a recent study on end‐of‐life care and cognitive status.26 Our results suggest that efforts to reduce end‐of‐life costs for people with dementia may not be an effective policy lever to lower Medicare costs.

Our study is one of only two that accounts for the mortality risk of dementia when estimating dementia‐associated costs,12 and it is the first study to explicitly separate the effects of dementia on intensity of health service utilization and survival time. Disentangling these effects is necessary both for understanding the magnitude of costs that are offset by reduced survival and understanding the potential cost implications of therapies that are life‐extending compared with interventions that reduce preventable inpatient and postacute care services. In our entire study sample, shorter survival time among participants with a dementia diagnosis—and in particular men with a dementia diagnosis—reduced the incremental cost by $2645. This suggests that longitudinal studies that do not account for differential mortality risk may be overestimating dementia attributable costs.

Mortality risk differences between men and women also resulted in significantly different incremental cost estimates for the two groups. Only one prior study has examined differences in dementia attributable costs between men and women.27 In their simulation study, Yang and Levey27 found a difference in lifetime incremental costs to the Medicare program of about $2300. Higher incremental costs among women were attributed to the higher lifetime probability of a dementia diagnosis among women. Our results suggest a much larger incremental cost difference between men and women due primarily to a differential mortality risk associated with dementia that was unaccounted for in the prior study. Future studies should further explore the contributions of sociodemographic characteristics to heterogeneity in dementia costs.

This study has several limitations. First, we identified participants with dementia using ICD‐9‐CM diagnosis codes in the Medicare claims, which may bias our cost estimates. Claims‐based diagnosis codes are likely to identify more severe dementia cases that are at a later stage of disease progression, potentially leading to an overestimation of costs. However, more severe dementia cases also have a shorter survival time, reducing total cost estimates. One study that evaluated the accuracy of dementia diagnoses in the Medicare claims using data from the subset of HRS participants who underwent a clinical cognitive examination reported a sensitivity of 0.85 and a specificity of 0.89.28 Second, we did not account for differential use of long‐term care services between our cases and controls. Long‐term care services are not covered by Medicare and greater use of these services by participants with dementia may influence Medicare cost differences. Further, incremental costs for total health care expenditure may differ from the patterns documented here for Medicare. Finally, our study was limited to an examination of the direct costs of medical care for patients with Medicare FFS insurance coverage, which represent only a portion of dementia cost considerations for families, public programs, and society. Additional studies are needed to estimate the direct costs of medical care for patients covered by Medicare Advantage plans and to estimate out‐of‐pocket costs for medical care with varying types of insurance coverage.

Our study also had a number of strengths. We used longitudinal data from a large, population‐based dataset to produce dementia attributable cost estimates based on health service utilization data from diagnosis until death. We linked health service use with survey data, which allowed us to include important sociodemographic covariates in our analyses that are unavailable in some other cost studies. Finally, we used a state‐of‐the‐art econometric approach that allowed us to distinguish between how dementia attributable mortality and intensity of health services use at the end of life drive health care costs.

Accurate estimates of the costs of dementia are required in order to properly plan and allocate health care resources. Our findings confirm that the cost of dementia to the traditional Medicare program is significant. Our estimates suggest that the 480 000 patients newly diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in 2017 cost traditional Medicare $2.7 billion in that year alone and will add an additional $3.2 billion to Medicare spending over the next 5 years.29 With the aging of the population and projected incidence of Alzheimer's disease, incremental spending in the first year of diagnosis among newly diagnosed patients could exceed $3.5 billion by 2030 and $5.5 billion by 2050, without accounting for inflation, and ignoring costs beyond the first year after diagnosis.30 The pattern of the costs incurred suggests that postponing the onset of the disease without impacting life expectancy would have little impact on the costs to traditional Medicare.31 However, interventions that aid in earlier identification of dementia and in the subsequent prevention of inpatient and postacute care services could lead to substantial savings within the program.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Lindsay White, Paul Fishman, Anirban Basu, Paul Crane, Eric Larson, and Norma Coe declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R01‐AG049815) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (SIP‐14‐005). We certify that we have no affiliation with or financial involvement in any organization or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

White L, Fishman P, Basu A, Crane PK, Larson EB, Coe NB. Medicare expenditures attributable to dementia. Health Serv Res. 2019;54:773–781. 10.1111/1475-6773.13134

REFERENCES

- 1. Langa KM, Larson EB, Crimmins EM, et al. A Comparison of the Prevalence of Dementia in the United States in 2000 and 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):51‐58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alzheimer's Association . What is dementia? 2016. http://www.alz.org/what-is-dementia.asp. Accessed November 5, 2016.

- 3. Larson EB, Yaffe K, Langa KM. New insights into the dementia epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(24):2275‐2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):63‐75 e62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bynum JP, Rabins PV, Weller W, Niefeld M, Anderson GF, Wu AW. The relationship between a dementia diagnosis, chronic illness, medicare expenditures, and hospital use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):187‐194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1326‐1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taylor DH Jr, Sloan FA. How much do persons with Alzheimer's disease cost Medicare? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(6):639‐646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weiner M, Powe NR, Weller WE, Shaffer TJ, Anderson GF. Alzheimer's disease under managed care: implications from Medicare utilization and expenditure patterns. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(6):762‐770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lin PJ, Zhong Y, Fillit HM, Chen E, Neumann PJ. Medicare expenditures of individuals with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias or mild cognitive impairment before and after diagnosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(8):1549‐1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS. The burden of health care costs for patients with dementia in the last 5 years of life. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):729‐736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lamb VL, Sloan FA, Nathan AS. Dementia and Medicare at life's end. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(2):714‐732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ayyagari P, Salm M, Sloan FA. Effects of diagnosed dementia on Medicare and Medicaid program costs. Inquiry. 2007;44(4):481‐494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yang Z, Zhang K, Lin PJ, Clevenger C, Atherly A. A longitudinal analysis of the lifetime cost of dementia. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(4):1660‐1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Basu A, Manning WG. Estimating lifetime or episode‐of‐illness costs under censoring. Health Econ. 2010;19(9):1010‐1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Chronic conditions data warehouse condition categories. www.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories. Accessed August 1, 2016.

- 16. Dunn A, Grosse SD, Zuvekas SH. Adjusting health expenditures for inflation: a review of measures for health services research in the United States. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(1):175‐196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alzheimer's Association . 2016 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(4):459‐509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Suehs BT, Davis CD, Alvir J, et al. The clinical and economic burden of newly diagnosed Alzheimer's disease in a medicare advantage population. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28(4):384‐392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gaugler JE, Hovater M, Roth DL, Johnston JA, Kane RL, Sarsour K. Analysis of cognitive, functional, health service use, and cost trajectories prior to and following memory loss. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68(4):562‐567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geldmacher DS, Kirson NY, Birnbaum HG, et al. Pre‐diagnosis excess acute care costs in Alzheimer's patients among a US Medicaid population. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(4):407‐413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McCormick WC, Kukull WA, van Belle G, Bowen JD, Teri L, Larson EB. The effect of diagnosing Alzheimer's disease on frequency of physician visits: a case‐control study. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(4):187‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhu CW, Cosentino S, Ornstein K, et al. Medicare utilization and expenditures around incident dementia in a multiethnic cohort. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(11):1448‐1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCormick WC, Kukull WA, van Belle G, Bowen JD, Teri L, Larson EB. Symptom patterns and comorbidity in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(5):517‐521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goldfeld KS, Stevenson DG, Hamel MB, Mitchell SL. Medicare expenditures among nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(9):824‐830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Phelan EA, Borson S, Grothaus L, Balch S, Larson EB. Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA. 2012;307(2):165‐172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nicholas LH, Bynum JP, Iwashyna TJ, Weir DR, Langa KM. Advance directives and nursing home stays associated with less aggressive end‐of‐life care for patients with severe dementia. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(4):667‐674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yang Z, Levey A. Gender differences: a lifetime analysis of the economic burden of Alzheimer's disease. Womens Health Issues. 2015;25(5):436‐440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Taylor DH Jr, Ostbye T, Langa KM, Weir D, Plassman BL. The accuracy of Medicare claims as an epidemiological tool: the case of dementia revisited. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17(4):807‐815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alzheimer's Association . 2017 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(4):325‐373. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hebert LE, Beckett LA, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Annual incidence of Alzheimer disease in the United States projected to the years 2000 through 2050. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15(4):169‐173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zissimopoulos J, Crimmins E, St Clair P. The value of delaying Alzheimer's disease onset. Forum Health Econ Policy. 2014;18(1):25‐39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials