Abstract

Objective

To investigate how changes in insurer participation and composition as well as state policies affect health plan affordability for individual market enrollees.

Data Sources

2014‐2019 Qualified Health Plan Landscape Files augmented with supplementary insurer‐level information.

Study Design

We measured plan affordability for subsidized enrollees using premium spreads, the difference between the benchmark plan and the lowest cost plan, and premium levels for unsubsidized enrollees. We estimated how premium spreads and levels varied with insurer participation, insurer composition, and state policies using log‐linear models for 15 222 county‐years.

Principal Findings

Increased insurer participation reduces premium levels, which is beneficial for unsubsidized enrollees. However, it also reduces premium spreads, leading to lower plan affordability for subsidized enrollees. States responding to cost‐sharing reduction subsidy payment cuts by increasing only silver plans' premiums increase premium spreads, particularly when premium increases are restricted to on‐Marketplace silver plans. The latter approach also protects unsubsidized, off‐Marketplace enrollees from experiencing premium shocks.

Conclusions

Insurer participation and insurer composition affect subsidized and unsubsidized enrollees' health plan affordability in different ways. Decisions by state regulators regarding health plan pricing can significantly affect health plan affordability for each enrollee segment.

Keywords: Affordable Care Act, health insurance, Health Insurance Marketplace

1. INTRODUCTION

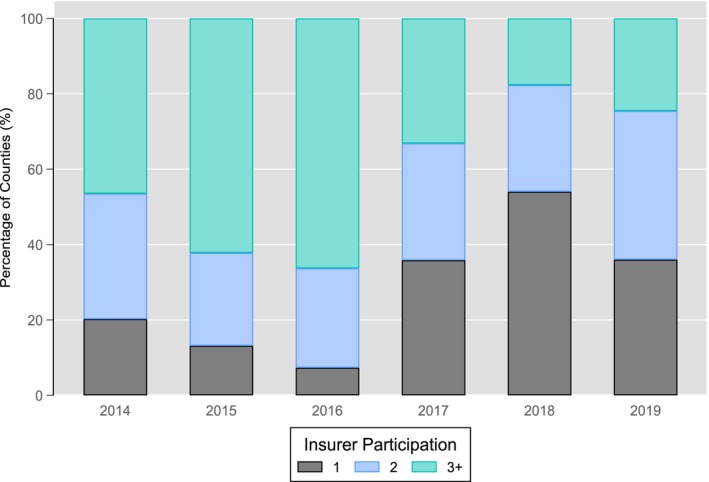

Insurer participation in the Federally Facilitated Marketplace (FFM) increased in 2019 for the first time since 2016. As shown in Figure 1, the number of monopoly counties—those with a single insurer—decreased by roughly one‐third from 1405 to 936. While overall premiums did not decrease substantially in 2019 despite increased insurer participation,1 empirical evidence has demonstrated that increased insurer participation and stronger competition are associated with lower premiums.2, 3, 4, 5 Premium levels represent a key outcome of interest to policy makers and the public because they are the most salient measure of health plan affordability in the individual market. Yet, for the 81 percent of Marketplace enrollees who receive advanced premium tax credits,6 the ability to afford health insurance is determined by the pricing of the second lowest cost silver plan premium (ie, the benchmark plan) relative to other plans offered in the market.

Figure 1.

Insurer participation in Federally Facilitated Marketplace counties from 2014 to 2019 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Notes. Data reflect all counties in 38 of the 40 states that used the Federally Facilitated Marketplace from 2014 to 2019. Alaska and Nebraska were excluded because insurers participate in their Marketplaces at the three‐digit zip code level rather than the county level. Some states only participated in the Federally Facilitated Marketplace in some years, such as Oregon (2015‐2019) and Kentucky (2016‐2019).

Given the advanced premium tax credit (APTC) program design, the difference or “spread” in premiums between the benchmark plan and the lowest cost plan determines the minimum cost at which a subsidized enrollee can purchase a Marketplace plan. As such, the premium spread is an important measure of plan affordability for subsidized enrollees. When the premium spread increases in magnitude, the postsubsidy premium of the lowest cost plan decreases for subsidized enrollees. In cases where enrollees’ incomes are sufficiently low and/or premium spreads are sufficiently large, enrollees may purchase the lowest cost plan for zero dollars out‐of‐pocket. Premium spreads expanded considerably in 2018 as a result of the Trump Administration's decision to cut cost‐sharing reduction (CSR) subsidies to insurers.7

Studies that have investigated plan affordability in the Marketplaces to date have focused almost exclusively on premiums.4, 8, 9, 10, 11 The literature has established that increased insurer competition results in lower Marketplace premiums.2, 3, 4, 5 Insurers operating in counties with multiple competitors have an incentive to lower premium levels because Marketplace consumers are very price sensitive with respect to health plan choice.12, 13, 14 Plans with lower premiums also are presented to consumers first when they search healthcare.gov, which positively affects choice.15, 16 However, no study to our knowledge has examined the relationship between insurer competition and premium spreads.

Economic theory suggests that the incentives facing insurers regarding premium spreads vary depending on competition.17, 18 Individual insurers in a competitive market have little control over premium spreads because it is unclear during the rate filing and regulatory review period—this occurs well in advance of open enrollment19which plan will be designated as the benchmark plan and which plan will become the lowest premium plan. Monopolist insurers, however, can unilaterally determine the size of the premium spread and have a strong incentive to increase it. By creating a large premium spread and thus making low‐ or zero‐premium plans available to subsidized enrollees, monopolists can attract enrollees into the Marketplaces who have lower willingness to pay for insurance. Even though insurers receive little to no direct premium revenue from such enrollees, they still receive large subsidy payments from the federal government. It is thus possible that plan affordability for subsidized enrollees (based on the premium spread) has an inverse relationship with insurer competition. Insurer behavior also may vary depending on insurers’ objective functions.20 For example, nonprofit insurers may seek to maximize enrollment rather than profits.

This article explores how insurer behavior affects health plan affordability in the FFM counties from 2014 through 2019 by examining how the number and type of insurers participating in FFM counties affect both premium levels and spreads. It also considers how Medicaid expansion decisions and states’ responses to CSR subsidy cuts affected premium levels and spreads. Unlike previous studies,2, 5, 21 we do not rely on cross‐sectional variation across counties to identify the effect of insurer participation on premiums. Instead, we use within‐county variation in insurer participation over time. This more robust approach allows us to control for all time‐invariant county characteristics in our analysis.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. Regulation of Health Insurance Marketplace premiums

The Health Insurance Marketplaces created by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) use a system of modified community rating for setting plan premiums. Under this system, insurers cannot vary the price of a given plan's premium except for predefined bands on the basis of an enrollee's age (3:1), smoking status (1.5:1), and geography. The latter prohibits insurers from varying premiums within clusters of counties known as rating areas, though insurers may selectively enter only certain counties within a rating area as a risk screening mechanism.22 The ACA also introduced greater plan standardization, such that each plan offered by insurers corresponds to an actuarial value “metal level,” including 60 percent for bronze, 70 percent for silver, 80 percent for gold, and 90 percent for platinum. The lowest cost plan in a county is typically a bronze plan, though this may not be the case if there are no bronze plans offered in the county.

Marketplace enrollees can receive advanced premium tax credits (APTCs) to reduce their out‐of‐pocket plan premium if they have modified adjusted gross incomes at or below 400 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), do not have an affordable offer of health insurance from an alternative source (eg, an employer), and do not qualify for public insurance such as Medicaid. The value of an enrollee's APTC is defined as the difference between the second lowest cost “benchmark” plan's premium and a designated percentage of household income. Specifically, APTCs reduce the premium an enrollee pays for the benchmark plan to an expected contribution amount that is a percentage of household income. In counties where only one silver plan is available, the sole silver plan is the benchmark plan.

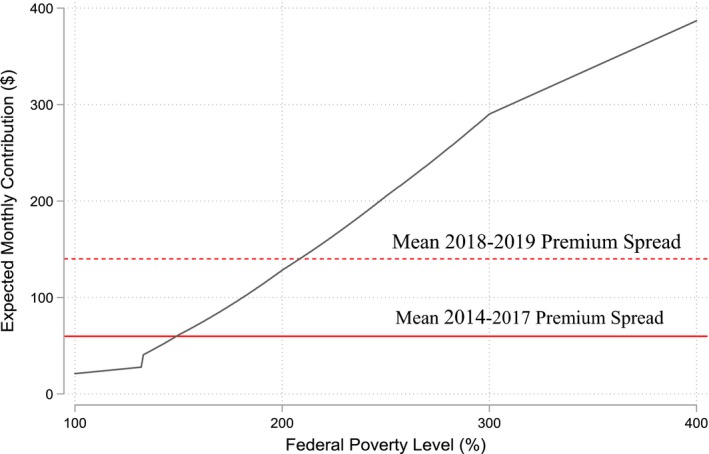

The amount an enrollee pays for a nonbenchmark plan is the enrollee's expected contribution amount less the difference between the premium of the benchmark plan and the nonbenchmark plan. For example, consider a single enrollee in 2018 whose income is 180 percent of the FPL. The expected monthly contribution amount for 180 percent of the FPL is roughly $100. Suppose that the pre‐APTC monthly premium of the benchmark plan available to the enrollee is $200 and that the pre‐APTC monthly premium of the lowest cost plan available to the enrollee is $140. The premium spread in this case is $60 (ie, the $200 benchmark premium less the $140 lowest cost plan premium). The enrollee would pay $40 for the lowest premium plan, which is equal to the enrollee's $100 expected monthly contribution amount less the $60 premium spread. The relationship between expected monthly contribution amounts by income and premium spreads is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Expected monthly contribution amounts for a subsidized marketplace enrollee [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Notes. A zero‐dollar plan is available to an enrollee when the premium spread is greater than or equal to the enrollee's expected monthly contribution amount. Expected monthly contributions increase slightly each year; displayed expected monthly contributions are for 2018.

2.2. Silver loading and increased premium spreads

On October 12, 2017, the Trump Administration announced it would cut cost‐sharing reduction (CSR) subsidy payments to insurers.23 Marketplace enrollees with incomes at or below 250 percent FPL qualify for CSR subsidies, which reduce their cost‐sharing (eg, copays, deductibles) obligations at the point of utilization and thereby increase the actuarial value of silver plans from 70 percent to 73 percent, 87 percent, or 94 percent depending on an enrollee's income. Even after the Administration cut CSR subsidy payments, insurers remain legally obligated to provide CSR plans to qualifying enrollees.

In response to the CSR payment cuts, 42 of 51 state insurance commissioners instructed insurers to silver load their premiums for the 2018 plan year.24, 25, 26 Three more states silver loaded in 2019.26 Under silver loading, insurers offset the expected loss of revenue from CSR subsidies by increasing the premiums of their silver plans, but not the premiums of plans of other metal levels. Since the benchmark plan is, by definition, a silver plan, silver loading resulted in large increases in premium differences between the benchmark plan and nonsilver plans. States that did not silver load implemented a broad load strategy under which all premiums increased to offset the lost revenue from the CSR subsidy payment cuts. Six states used a broad load approach in 2018 (CO, DE, IN, MS, OK, and WV); three did in 2019 (IN, MS, and WV).

There are two forms of silver loading: on‐ and off‐Marketplace silver loading and on‐Marketplace only silver loading. Under the former approach, both on‐ and off‐Marketplace silver plans’ premiums are increased to offset CSR subsidy payment losses. Eighteen states used on‐ and off‐Marketplace silver loading in 2018; nineteen did in 2019.26 The latter approach, referred to in the gray literature as the “silver switcharoo,”27 was implemented by 24 states in 2018 and 29 states in 2019.26 Under on‐Marketplace only silver loading, silver premiums are increased for on‐Marketplace silver plans only. Silver plans in the off‐Marketplace do not contain the markup to offset CSR subsidy payment cuts. This is made possible by state insurance commissioners allowing insurers to sell off‐Marketplace plans that are very similar but not identical to on‐Marketplace plans in terms of benefits. These variant plans do not contain offsets for CSR subsidy cuts. This strategy thus shields off‐Marketplace enrollees from premium increases due to CSR subsidy cuts.

Silver loading increased premium spreads in 2018 to the point that a nonsmoking 40‐year‐old adult making $25 000 could purchase at least one bronze plan for zero dollars in 1679 counties.7 As shown in Figure 2, mean 2014‐2017 premium spreads allowed single enrollees at or below 149 percent of the FPL to purchase the lowest premium plan for zero dollars. After CSR cuts, mean premium spreads increased such that in 2018‐2019, enrollees at or below 208 percent of the FPL could purchase the lowest premium plan for zero dollars. Accordingly, 2018 saw increases in bronze and gold plan enrollment and a decrease in silver plan enrollment.24 It is not clear, however, whether these changes were due to existing enrollees switching away from silver plans or new enrollees joining the FFM due to the availability of zero‐dollar premium plans. Regardless, increased premium spreads have increased the affordability of plans available to subsidized Marketplace enrollees.

3. METHODS

3.1. Data and study population

Our primary data source was the 2014‐2019 Qualified Health Plan Landscape File made available by healthcare.gov (QHP). The QHP lists every health plan available in the FFM at the county level, including premiums, deductibles, metal level, and the insurer offering the plan. We augmented the QHP data with insurer characteristics from the 2014‐2016 Annual Filing Statements of the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), the 2014‐2016 Center for Consumer Information and Oversight MLR filing data, and the Kaiser Family Foundation's listing of Medicaid managed care organizations,28 to characterize the types of insurers selling insurance in the FFM.

Our unit of analysis was the county‐year, since Marketplace insurers choose to offer plans at the county level on an annual basis. Our sample included 38 of the 40 states that used the FFM from 2014 to 2019. We excluded Alaska and Nebraska, which define their rating areas at the three‐digit zip code rather than the county level. Some states, such as Hawaii, Kentucky, and Oregon, did not use the FFM in all years; we included them in the years that they used it. Our final analytic sample consisted of 15 222 county‐years representing 2646 counties.

3.2. Outcomes and measures

We examined two outcomes that reflect health plan affordability for FFM enrollees. First, we examined the minimum silver premium, defined as the pre‐APTC monthly premium of the lowest cost silver plan available to a 30‐year‐old, nonsmoking adult. Minimum silver premiums capture the lowest price at which an unsubsidized enrollee may purchase a silver plan in the county‐year. Even after CSR payment cuts, silver plans have remained the most popular choice among FFM enrollees.6

Second, to measure plan affordability for enrollees qualifying for APTCs, we examined the premium spread, defined as the difference in monthly premiums between the benchmark plan and the lowest cost plan. As the premium spread increases, the monthly premium that an enrollee must pay to purchase the lowest cost plan decreases. Holding an enrollee's income constant, an increasing percentage of subsidized enrollees gain access to zero‐dollar premium plans as premium spreads increase. As shown in Figure 2, at mean premium levels across FFM counties, zero‐dollar plans were available to single enrollees with incomes at or below 149 percent of the FPL from 2014 to 2017. When CSR payments were not paid in 2018 and 2019, they became available to single enrollees with household incomes up to 208 percent of the FPL at mean premium levels.7

We explored how minimum silver premiums and premium spreads vary according to the number and composition of insurers in a county. The literature indicates that most of the gains from competition in the individual market are realized in markets with three competing insurers.2, 5 Accordingly, we categorized insurer participation as markets with one insurer, two insurers, or three or more insurers in a given county‐year. We characterized the composition of insurers in a county‐year based on whether certain types of insurers are present. For this purpose, we grouped insurers into four mutually exclusive categories: (1) Blue Cross Blue Shield insurers; (2) Big four insurers (UnitedHealth Group; Humana, Aetna, Cigna); (3) Medicaid managed care insurers (eg, Centene, Molina); and (4) other.

We also controlled for whether a county was located in a state that had expanded Medicaid as reported by the Kaiser Family Foundation.29 It has been shown that insurers tend to decrease premiums when they can anticipate that a state will expand Medicaid.30 Accordingly, we set the Medicaid expansion indicator equal to one only if a given state had expanded Medicaid by September of the preceding year. Finally, we controlled for whether a state used on‐ and off‐Marketplace silver loading or only on‐Marketplace silver loading in 2018 and 2019 as reported by Gaba et al26 Broad loading was the reference category.

3.3. Statistical analysis

We used multivariate linear regression at the county‐year level to examine associations of insurer participation and composition with our outcomes, which we transformed to be the logs of minimum premiums and premium spreads to account for their skewed distributions. We estimated our models at the county rather than the rating area level because insurers can choose to participate in individual counties even though they must price their plans uniformly within rating areas.2, 18, 22 We included county fixed effects in our models to account for time‐invariant county demographic characteristics, county provider characteristics, and state regulatory characteristics. We also included year fixed effects to capture overarching changes in the FFM over time, such as federal changes in actuarial value bands.31 Finally, we included state‐year indicators for whether a county is in a state that expanded Medicaid and the type of silver loading used in a given year. We clustered standard errors at the rating area level to account for the regulation that insurers may not vary plan characteristics for the same plan across counties within the same rating area.

We relied on within‐county variation in insurer participation over time to identify the effect of insurer participation on premium levels and premium spreads. As shown in Figure 1, the FFM has experienced considerable variation in insurer participation over the study period. For example, from 2016 to 2017, the percentage of counties with one participating insurer increased from 7.34 percent to 35.85 percent. Unlike previous studies that used cross‐sectional variation across counties to identify the effect of insurer participation on premiums,2, 5, 21 this more robust approach allows us to control for all time‐invariant county characteristics that could influence our outcomes through the use of county fixed effects. Our identification strategy is similar for state policies in that we relied on within‐county variation in exposure to state policies over time to identify state policy effects. Numerous states expanded Medicaid after 2014,29 and there is substantial variation in silver loading strategies across time and states.26

3.4. Limitations

We acknowledge three limitations. First, our model does not control for demographic or provider market changes within counties over this time period. While our insurer participation and composition variables account for changes among insurers over time, large demographic or provider market changes over time may introduce bias into our model. Large demographic changes over a six‐year period, however, are uncommon. Additionally, our use of county fixed effects in our model addresses time‐invariant county characteristics that previous studies with cross‐sectional research designs could not. While it is possible that provider consolidation activity from 2014 to 2019 could introduce bias to our model estimates, it is not possible to sign the bias. Second, our analysis is focused on plan affordability and does not address other downstream, out‐of‐pocket costs that enrollees could incur at the point of utilization, such as deductibles and copayments. Third, our analysis is limited to Marketplace plans in FFM states and may not generalize to State‐Based Marketplaces.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Descriptive statistics

As shown in Table 1, the mean minimum silver premium was $360.17 per month across the study period after adjusting for inflation. Average, minimum silver premiums increased from $269.45 in 2014 to a high of $468.17 in 2018, with a slight reduction to $452.10 in 2019. We observed an inverse relationship between minimum silver premiums and insurer participation—from $428.28 in monopoly counties to $294.09 in counties with three or more insurers.

Table 1.

Plan affordability and insurer composition by insurer participation and time, N = 15 222

| Insurer participation | Year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3+ | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Affordability (Monthly $) | |||||||||

| Minimum silver premium | 428.28 | 363.77 | 294.09 | 269.45 | 268.69 | 292.26 | 356.93 | 468.17 | 452.1 |

| premium spread | 111.94 | 95.81 | 65.32 | 58.65 | 57.36 | 55.23 | 68.32 | 133.52 | 147.94 |

| Insurer composition | |||||||||

| Blue cross blue shield | 73.11 | 75.42 | 87.09 | 85.37 | 85.30 | 83.71 | 84.92 | 65.69 | 73.34 |

| big four | 4.07 | 30.90 | 46.64 | 37.86 | 56.34 | 68.83 | 13.00 | 2.96 | 3.62 |

| Medicaid managed care | 16.24 | 35.86 | 55.91 | 33.00 | 38.29 | 39.11 | 36.19 | 40.00 | 44.90 |

| Other | 6.59 | 38.36 | 75.15 | 52.13 | 50.08 | 45.60 | 39.42 | 37.38 | 43.86 |

Premiums are inflated to 2019 dollars using the medical CPI. Big four insurers include Aetna, Cigna, Humana, and United. Blue Cross Blue Shield includes all affiliated insurers. Medicaid managed care includes nonbig four, non‐Blue Cross Blue Shield insurers with a presence in their state's Medicaid managed care market.

Mean premium spreads were roughly $60 from 2014 through 2017. They increased sharply to $133.52 and $147.94 in 2018 and 2019, respectively, following the Administration's decision to eliminate CSR subsidy payments. Unlike minimum silver premiums, premium spreads were inversely related to insurer participation and ranged from an average of $111.94 in monopoly counties to $65.32 for counties with three or more insurers.

Table 1 also summarizes insurer composition by insurer participation and over time. Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) insurers were the monopolist insurer in 73.11 percent of county‐years in the sample. Medicaid managed care (MMC) insurers were the monopolist insurer in 16.24 percent of county‐years, and other insurers made up the remaining 10.66 percent. Insurers with BCBS affiliation were present in over 80 percent of FFM counties through 2017. They reduced their presence to 65.69 percent in 2018 and then increased it to 73.34 percent of counties in 2019. Medicaid managed care insurers participated in roughly 40 percent of FFM counties over time. Unlike other types of insurers, big four insurers did not increase their presence in the FFM in 2019 after exiting over 50 percent of counties in 2017.

4.2. Regression analysis

Regression analysis results are shown in Table 2. We regressed log minimum silver premiums on insurer participation, insurer composition indicators, time‐varying state policies, and county and year fixed effects. Relative to counties with three or more insurers and all else held constant, minimum silver premiums were 8.47 percent higher (P < 0.001) in counties with two insurers and 18.47 percent higher (P < 0.001) in counties with one insurer. Relative to the mean 2019 monthly minimum silver premium of $452.10, these coefficients may be interpreted as $38.30 and $83.50 increases in minimum silver premiums. We also found that minimum silver premiums are 14.59 percent higher (P < 0.001) in counties with BCBS insurers, 8.10 percent lower (P < 0.01) in counties with Medicaid managed care insurers, and 8.91 percent lower (P < 0.05) in counties in Medicaid expansion states. These percentages equate to 2019 minimum silver premium changes of $65.96, −$36.62, and −$40.28, respectively. Counties in on‐ and off‐Marketplace silver loading and on‐Marketplace only silver loading states were associated with minimum silver premiums that were 17.14 percent (P < 0.001) and 18.67 percent (P < 0.001) higher, corresponding to 2019 minimum silver premium increases of $77.49 and $84.41, respectively. Year fixed effects suggest large minimum silver premium increases over time relative to 2014 even after controlling for inflation.

Table 2.

Percentage changes in minimum silver premiums, premium spreads

| Log minimum silver premium | Log premium spread | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage change | Coefficient | Standard error | Percentage change | Coefficient | Standard error | |

| Insurer participation | ||||||

| 1 insurer | 18.47 | 0.170*** | 0.022 | 34.56 | 0.297*** | 0.052 |

| 2 insurers | 8.47 | 0.081*** | 0.014 | 15.01 | 0.140*** | 0.034 |

| 3+ insurers (reference) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Insurer composition | ||||||

| Blue cross blue shield | 14.59 | 0.136*** | 0.022 | 57.43 | 0.454*** | 0.055 |

| Big four | −0.99 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 13.32 | 0.125** | 0.038 |

| Medicaid managed care | −8.1 | −0.085** | 0.027 | −16.32 | −0.178** | 0.067 |

| Other | 6.58 | 0.064*** | 0.018 | 16.95 | 0.157*** | 0.043 |

| State insurance policies | ||||||

| Medicaid expansion | −8.91 | −0.093* | 0.04 | −15.51 | −0.169 | 0.106 |

| Silver load: broad load | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Silver load: on and off | 17.14 | 0.158*** | 0.041 | 78.47 | 0.579*** | 0.099 |

| Silver load: only on | 18.67 | 0.171*** | 0.038 | 121.18 | 0.794*** | 0.106 |

| Year | ||||||

| 2014 (reference) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 2015 | 2.85 | 0.028** | 0.01 | 1.53 | 0.015 | 0.028 |

| 2016 | 14.63 | 0.137*** | 0.014 | −2.26 | −0.023 | 0.033 |

| 2017 | 31.86 | 0.277*** | 0.031 | 11.83 | 0.112* | 0.052 |

| 2018 | 50.79 | 0.411*** | 0.051 | 32.53 | 0.282* | 0.114 |

| 2019 | 46.69 | 0.383*** | 0.051 | 36.06 | 0.308* | 0.12 |

| Constant | 22 541.91 | 5.422*** | 0.032 | 3233.78 | 3.507*** | 0.083 |

| R‐Squared | 0.85 | 0.73 | ||||

| Sample size | 15 222 | 15 218 | ||||

Percentage changes are calculated as one minus the exponentiated coefficient times 100. Both models include county fixed effects. Insurer composition variables are indicators for whether any insurer of the given type is present. Premiums are inflated to 2019 dollars using medical CPI. The log premium spread has four missing observations for counties where the premium spread is zero and the log of the premium spread is undefined.

*P < 0.05.

**P < 0.01.

***P < 0.001.

We also report results for the log premium spread model in Table 2. Relative to counties with three or more insurers, premium spreads were 14.00 percent higher (P < 0.001) in counties with two insurers and 29.70 percent higher (P < 0.001) in counties with one insurer. Relative to the 2019 mean premium spread of $147.83, these coefficients may be interpreted as $22.19 and $51.09 increases in premium spreads. Counties with BCBS insurers were associated with premium spreads that were 57.43 percent higher (P < 0.001) relative to those without, while counties with Medicaid managed care insurers were associated with premium spreads that were 16.32 percent (P < 0.01) lower. Medicaid expansion was not associated with log premium spreads. On‐ and off‐Marketplace silver loading and on‐Marketplace only silver loading had large effects on premium spreads of 78.47 percent (P < 0.001) and 121.18 percent (P < 0.001), corresponding to $116.00 and $179.14 increases in 2019 premium spreads, respectively. The positive significance of the 2018‐ and 2019‐year fixed effects is consistent with the shock resulting from the change of policy regarding the payment of CSR subsidies to insurers.

4.3. Sensitivity analyses

We conducted four sensitivity checks. First, we assessed the sensitivity of our results to different categorizations of insurer participation. Our results were robust to classifying the most competitive markets as having four or more and five or more insurers. Second, we tested whether creating a separate category for states that allowed but did not require insurers to silver load their premiums affected our results. In our baseline models, we coded states that allowed but did not require insurers to silver load as on‐ and off‐Marketplace silver loading states. Six states used this approach in 2018 (AZ, GA, MT, NM, IL, and TX), and two did so in 2019 (IL and TX). When we placed these states into their own category, changes to our results were negligible. Third, we estimated our models at the rating area level rather than the county level. Our results were unchanged except for the association between having two insurers in the rating area‐year and log minimum silver premiums, which was no longer significant. We thus interpret this result with caution. Fourth, we interacted the BCBS and Medicaid managed care composition variables with insurer participation to examine whether strategies employed by these types of insurers under varying levels of competition affect our outcomes. We do not find evidence that either BCBS or Medicaid managed care insurers changed their pricing behavior based on the degree of competition they faced.

5. DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that the number and composition of insurers as well as states’ responses to CSR payment cuts have important implications for coverage affordability among subsidized and unsubsidized enrollee populations. Specifically, insurer monopoly in the FFM is associated with higher premium levels and premium spreads. For a county in 2019 with average premiums, reducing insurer participation from three or more insurers to one insurer is associated with an $84 monthly premium increase for the lowest cost silver plan for a single 30‐year‐old adult. For premium spreads, we find the opposite pattern. Moving from three or more insurers to one insurer is associated with a $51 increase in the premium spread, meaning that the cost to the consumer of the least expensive Marketplace plan decreases by $51.

We also find composition effects. The presence of a BCBS insurer is associated with significantly higher premiums, while Medicaid managed care plan presence is associated with lower minimum silver premiums. One potential explanation for this pattern is that the set of plans offered by BCBS and Medicaid managed care organizations may differ on dimensions not captured in the Qualified Health Plan Landscape Files. One such example is the breadth of the provider network. Evidence from the 2017 Marketplaces14, 32 suggests that BCBS plans tend to have broader networks as compared to Medicaid managed care plans, and we know that there is a positive association between provider network breadth and premiums.33, 34 A second potential explanation is that enrollees may perceive the BCBS brand to be of higher quality relative to other brands. It is important to note that systematic differences in the counties and/or states where BCBS insurers operate cannot explain our findings, as we control for all time‐invariant county and associated state characteristics in our models.

Our models also reveal that premium spreads are higher in counties with BCBS insurers. This is particularly important given that BCBS is the monopolist in over 70 percent of the monopoly counties in the FFM. Insurers may differ in their objectives.20 If maximizing enrollment reflects the primary objective of certain types of insurers, then establishing large premium spreads may be one way to accomplish this goal. Monopolists are able to generate large revenue increases when Marketplace enrollment increases because they collect sizable APTCs from the federal government. At the same time, they can still charge higher premiums for more generous plans to enrollees with greater demand for such benefits. Monopolists face very little risk of losing subsidized enrollees from pricing too high due to the structure of premium tax credits, which cap an enrollee's out‐of‐pocket contribution for the benchmark plan based on income.

Findings from this study also illustrate the large impact of state‐based insurance regulatory decisions in response to federal policy shifts. Specifically, in response to the CSR payment cuts, most states responded by encouraging insurers to build anticipated CSR payment revenue losses into premiums.24 Differences in states’ silver loading strategies likely had different effects on enrollees. While higher premium levels may dissuade unsubsidized enrollees from buying Marketplace coverage, insurers in on‐Marketplace only silver loading states can offer unsubsidized enrollees lower‐priced, similar plans in the off‐Marketplaces with regulatory approval. This is not possible in states that silver loaded across the on‐ and off‐Marketplace, which may explain why we observe a stronger association between premium spreads and counties in on‐Marketplace only silver loading states (121 percent) relative to on‐ and off‐Marketplace silver loading states (78 percent). That is, insurers do not have as strong of an incentive to create large premium spreads when doing so means they will lose enrollees in the off‐Marketplace. On‐Marketplace only silver loading and offering nearly equivalent silver plans in the off‐Marketplaces thus provide state policy makers with an effective tool to simultaneously increase plan affordability throughout the individual market, both on and off the Marketplaces. As of 2019, 22 states have not implemented on‐Marketplace only silver loading.26

While the unintended consequences of CSR payment cuts have led to increased affordability for some enrollees, particularly those in states that silver loaded only on‐Marketplace plans, there are some important downstream effects. First, if incumbent enrollees switched from silver to bronze plans as a result of CSR payments cuts, they may have increased their potential financial exposure to medical expenses. Sprung and Anderson found an increase in bronze plan enrollment following CSR cuts,24 but it remains unclear whether this increase is primarily due to new enrollees entering the Marketplace in bronze plans or incumbent enrollees switching away from more generous plans. Second, pricing distortions created by silver loading have led to higher premium tax credits and federal spending.35 Larger premium spreads which came about because of the CSR payment cuts and silver loading have increased affordability as an unintended consequence of the Administration's attempt to punish Marketplace insurers.

The affordability of health insurance coverage in the individual market continues to be a fundamental issue facing state and federal policy makers. Looking ahead, states will need to develop and implement strategies to ensure affordable options and promote stability in the individual market. For each policy approach, there will be costs, perhaps unintended, that are born by enrollees and/or taxpayers. Notable approaches, to date, include California's aggressive active purchaser model,36 premium relief measures in Minnesota,37 the creation of reinsurance programs through 1332 State Innovation Waivers,38 and Medicaid buy‐in programs in New Mexico and Nevada.39 In the context of our study, we find that the on‐Marketplace only silver loading that was an unintended consequence of CSR subsidy cuts increased affordability for subsidized and unsubsidized enrollees. Both forms of silver loading are costless to the states and may even be a boon to state budgets by decreasing the number of uninsured and uncompensated care costs. However, the Administration's decision to cut CSR payments has increased the cost to federal taxpayers of providing on‐Marketplace enrollees with larger premium tax credits.35

6. CONCLUSION

We find that lower insurer participation decreases plan affordability for unsubsidized Marketplace enrollees by increasing premium levels, but that it increases plan affordability for Marketplace enrollees who qualify for APTCs by increasing premium spreads between the benchmark silver plan and the lowest cost plan. The decision by the Trump Administration to eliminate CSR subsidy payments to insurers and the subsequent silver loading of premiums created an incentive structure that encourages monopolists to price their plans such that enrollees with APTCs have access to plan options with very small or even zero‐dollar premiums.

Whether and how states silver load the premiums of Marketplace plans has a large impact on affordability by increasing premium spreads and thus affordability for subsidized enrollees. In the case of on‐Marketplace only silver loading, off‐Marketplace enrollees are shielded from premium shocks related to cost‐sharing reduction subsidy payment cuts. While all but three states—Indiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia—have implemented some form of silver loading, 22 states have yet to implement on‐Marketplace only silver loading that increases affordability for both on‐ and off‐Marketplace enrollees.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: The authors would like to acknowledge the constructive comments provided by the editors and anonymous reviewers. Support for this research was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation under grant award #75027. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimer: None.

Drake C, Abraham JM. Individual market health plan affordability after cost‐sharing reduction subsidy cuts. Health Serv Res. 2019;54:730–738. 10.1111/1475-6773.13190

REFERENCES

- 1. Groppe M. Trump Administration Touts 2019 drop in average Obamacare premiums after big increases this year. USA Today https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2018/10/11/obamacare-premiums-dropping/1598934002/. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- 2. Abraham J, McCullough JS, Drake C, Simon K. What drives insurer participation and premiums in the federally‐facilitated marketplace? Int J Heal Econ Manag. 2017;17:395‐412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sacks DW, Vu K, Huang T‐Y, Karaca‐Mandic P. The effect of the risk corridors program on marketplace premiums and participation. NBER Work Pap 2017;24129.

- 4. Dafny L, Gruber J, Ody C. More insurers lower premiums: evidence from initial pricing in the Health Insurance Marketplaces. Am J Heal Econ. 2015;1(1):53‐81. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sheingold S, Nguyen N, Chappel A. Competition and Choice in the Health Insurance Marketplaces, 2014-2015: Impact on Premiums, Issue Brief. Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. July 27, 2015. http://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/108466/rpt_MarketplaceCompetition.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Health Insurance Marketplaces 2017 Open Enrollment Period: January Enrollment Report. 2017;4 https://downloads.cms.gov/files/final-marketplace-mid-year-2017-enrollment-report-1-10-2017.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- 7. Semanskee A, Claxton G, Levitt L. How premiums are changing in 2018. Kaiser Fam Found 2017. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/how-premiums-are-changing-in-2018/. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- 8. Scheffler RM, Arnold DR, Fulton BD, Glied SA. Differing impacts of market concentration on affordable Care Act Marketplace Premiums. Health Aff. 2016;35(5):880‐888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jacobs PD, Banthin JS, Trachtman S. Insurer competition in federally run marketplaces is associated with lower premiums. Health Aff. 2015;34(12):2027‐2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gabel JR, Arnold DR, Fulton BD, et al. Consumers buy lower‐cost plans on covered California, suggesting exposure to premium increases is less than commonly reported. Health Aff. 2017;36(1):8‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van Parys J. ACA marketplace premiums grew more rapidly in areas with monopoly insurers than in areas with more competition. Health Aff. 2018;37(8):1243‐1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abraham J, Drake C, Sacks DW, Simon K. Demand for Health Insurance Marketplace plans was highly elastic in 2014‐2015. Econ Lett. 2017;159:69‐73. [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeLeire T, Marks C. Consumer decisions regarding Health Plan Choices in the 2014 and 2015 marketplaces. Off Assist Secr Plan Eval. 2015;21 https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/134556/Consumer_decisions_10282015.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drake C. What are consumers willing to pay for a broad network health plan?: Evidence from covered California. J Health Econ. 2019;65:63‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ryan M, Krucien N, Hermens F. The eyes have it: using eye tracking to inform information processing strategies in multi‐attributes choices. Health Econ. 2018;27:709‐721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diamond R, Dickstein MJ, Mcquade T, Persson P. Take‐up, drop‐out, and spending in ACA marketplaces. NBER Work Pap 2018;24668. http://www.nber.org/papers/w24668.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2018.

- 17. Anderson D. Evolving insurer business strategies on the individual marketplace. AcademyHealth 2018 Annual Research Meeting.

- 18. Anderson D. Insurer market concentration. Health Aff. 2018;37(10):1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight . 2020 Draft letter to issuers in the federally‐facilitated exchanges. Centers Medicare Medicaid Serv. 2019;5-7. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Regulations-and-Guidance/Downloads/Draft-2020-Letter-to-Issuers-in-the-Federally-facilitated-Exchanges.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20. Feldman R. Equilibrium in monopolistic Insurance Markets: an extension to the sales‐maximizing monopolist author. J Risk Insur. 1982;49(4):602‐612. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Polsky D, Cidav Z, Swanson A. Marketplace plans with narrow physician networks feature lower monthly premiums than plans with larger networks. Health Aff. 2016;35(10):1842‐1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fang H, Ko A. Partial rating area offering in the ACA marketplaces: facts, theory, and evidence. Work Pap 2018.

- 23. Jost T. Administration's ending of cost‐sharing reduction payments likely to roil individual markets. Health Affairs Blog. 2017. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20171022.459832/full/. Accessed March 4, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sprung A, Anderson D. Mining the silver lode. Health Affairs Blog. 2018. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180904.186647/full/. Accessed October 27, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Corlette S, Lucia K, Kona M. States step up to protect consumers in wake of cuts to ACA cost‐sharing reduction payments. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2017/states-step-protect-consumers-wake-cuts-aca-cost-sharing-reduction-payments. Published 2017. Accessed March 4, 2019.

- 26. Gaba C, Anderson D, Norris L, Sprung A. 2019 CSR Load Type. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1N8NxRjhv6jcRqWZNQaphecbquSquBGd5szCJOkiGYjI/edit#gid=0. Published 2018. Accessed February 17, 2019.

- 27. Frakt A. Cost sharing reduction weeds: “Silver loading” and the “silver switcheroo” explained. The Incidental Economist. https://theincidentaleconomist.com/wordpress/cost-sharing-reduction-weeds-silver-loading-and-the-silver-switcheroo-explained/. Published 2017. Accessed February 17, 2019.

- 28. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation . Medicaid MCOs and Their Parent Firms. kff.org. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/medicaid-mcos-and-their-parent-firms/?currentTimeframe=0. Published 2018. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- 29. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation . Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision. kff.org. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Published 2019. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- 30. Peng L. How does Medicaid expansion affect premiums in the Health Insurance Marketplaces? New evidence from late adoption in Pennsylvania and Indiana. Am J Heal Econ. 2017;3(4):550‐576. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Newsroom . CMS issues final rule to increase choices and encourage stability in health insurance market for 2018. cms.gov.

- 32. Polsky D, Weiner J, Zhang Y. Narrow Networks on the Individual Marketplace in 2017. Leonard Davis Inst Heal Econ. 2017. https://ldi.upenn.edu/brief/narrow-networks-individual-marketplace-2017. Accessed October 27, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Polsky D, Weiner J. The skinny on narrow networks in Health Insurance Marketplace Plans. Leonard Davis Inst Heal Econ. 2015. http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2015/rwjf421027. Accessed October 27, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dafny LS, Hendel I, Marone V, Ody C. Narrow networks on the Health Insurance Marketplaces: prevalence, pricing, and the cost of network breadth. Health Aff. 2017;36(9):1606‐1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Congressional Budget Office . The Effects of Terminating Payments for Cost‐Sharing Reductions. August 2017. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/53009-costsharingreductions.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2018.

- 36. Bingham A, Cohen M, Bertko J. National vs. California Comparison: detailed data help explain the risk differences which drive covered California's success. Health Affairs Blog. 2018. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180710.459445/full/. Accessed September 30, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Financial Audit Division . Premium Subsidy Program. Off Legis Audit State Minnesota 2018.

- 38. Drake C, Blewett L, Fried B. Estimated costs of a reinsurance program to stabilize the individual health insurance market: National‐ and state‐level estimates. Inq J Heal Care Organ Provision Financ. 2019;56. 0046958019836060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ollove M. Medicaid ‘Buy‐In’ could be a new health‐care option for the uninsured. Governing the States and Localities http://www.governing.com/topics/health-human-services/sl-medicaid-buy-in-uninsured.html. Accessed January 10, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials