Abstract Abstract

A checklist of the amphibians of Santa Teresa municipality, in southeastern Brazil is presented based on fieldwork, examination of specimens in collections, and a literature review. This new amphibian list of Santa Teresa includes 108 species, of which 106 (~98%) belong to Anura and two (~2%) to Gymnophiona. Hylidae was the most represented family with 47 species (43%). Compared to the previous amphibian lists for Santa Teresa, 14 species were added, 17 previously reported species were removed, and 13 species were re-identified based on recent taxonomic rearrangements. Of the 14 species added, 11 (79%) were first recorded during our fieldwork and specimen examination. It is also the first list of caecilians for Santa Teresa. This list suggests that Santa Teresa has 0.16 species per km2 (i.e., 108 species/683 km2), one of the highest densities of amphibian species in the world at a regional scale. This richness represents 78% of the 136 anurans from Espírito Santo state and 10% of the 1,080 amphibians from Brazil. We highlight the need for long-term monitoring to understand population trends and develop effective conservation plans to safeguard this remarkable amphibian richness.

Keywords: Anura , Atlantic Forest, Caecilians, Diversity, Espírito Santo, Inventory

Introduction

Species checklists provide a scientific value to areas by identifying the richness that is threatened given anthropogenic actions. The Brazilian Amphibian Conservation Action plan recognizes that species lists are a scientific priority for many areas across Brazil (Verdade et al. 2012). For instance, Brazil’s Atlantic Forest is one of the most threatened global biodiversity hotspots and remains under-sampled given the high number of new species recently described (Lourenço-de-Moraes et al. 2014, Ferreira et al. 2015, Marciano-Jr et al. 2017). The Atlantic Forest has currently 12% of its historical range, which has resulted in the replacement of continuous forest to small remnants surrounded by human settlements, pastures, plantations, and roads (Ribeiro et al. 2009, Tabarelli et al. 2010). Thus, compiling data regarding the biodiversity of this tropical forest is a conservation priority, especially because several studies have detected changes and declines of some species (Heyer et al. 1988, Weygoldt 1989, Carvalho et al. 2017).

The Atlantic Forest harbors 625 anuran species and 14 caecilians (Rossa-Feres et al. 2017). The state of Espírito Santo, southeastern Brazil harbors 136 (22%) species listed for Atlantic Forest. The state’s most sampled area is the municipality of Santa Teresa, which comprises high functional and phylogenetic diversity of amphibians (Almeida et al. 2011, Campos et al. 2017, Lourenço-de-Moraes et al. 2019). There are conflicting reports regarding the species composition and richness in this area. The first species list for Santa Teresa recorded 102 anuran species (Rödder et al. 2007). However, the state list of anurans mentioned 92 species for Santa Teresa (Almeida et al. 2011). In recent years, new species have been described for Santa Teresa (e.g., Lourenço-de-Moraes et al. 2014, Ferreira et al. 2015, Taucce et al. 2018), some species have been reported for the first time in the area (Simon and Peres 2012), and there have been many taxonomic changes (e.g., Pimenta et al. 2014, Walker et al. 2016), indicating the need to update the species list of this anuran diversity hotspot.

Santa Teresa is also a hotspot for several other taxa, such as plants (Thomaz and Monteiro 1997), birds (Simon 2000), butterflies (Brown and Freitas 2000), and small mammals (Passamani et al. 2000). Due to its remarkable biological importance, it is essential to keep the species lists updated. Here, we present an updated species list of the amphibians for Santa Teresa based on many years of fieldwork, examination of specimens from scientific collections, and literature review.

Materials and methods

Study area

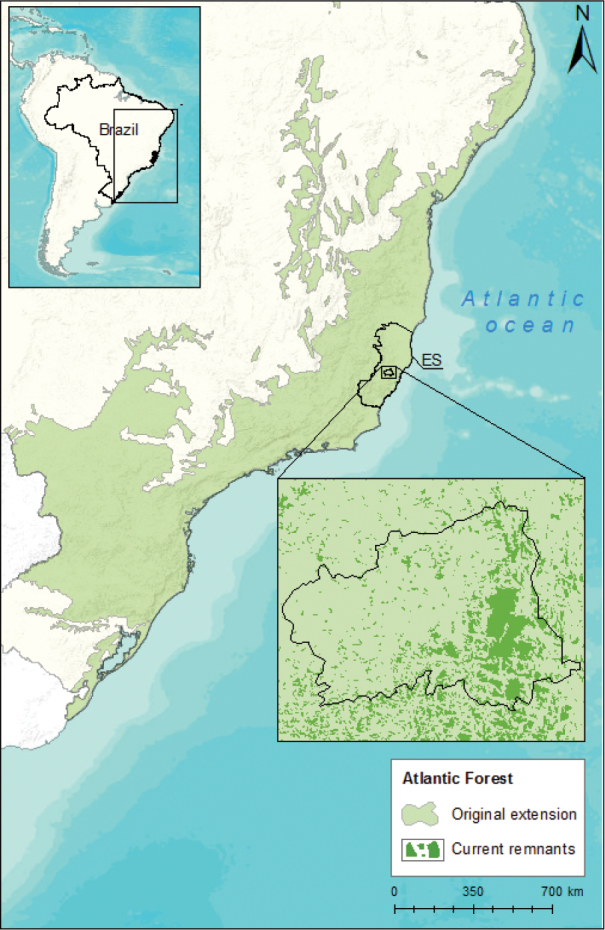

The municipality of Santa Teresa has 683 km2 and is located in the mountainous region (altitude range: ~120–1099 m a.s.l.) of Espírito Santo state, southeastern Brazil (19°56'14"S, 40°35'52"W; Figure 1). Santa Teresa encompasses the southern portion of Bahia Coastal Forests ecoregion, and northern portion of Serra do Mar ecoregion in the Atlantic Forest (Olson et al. 2001, Scaramuzza et al. 2011, Campos and Lourenço-de-Moraes 2017, Silva et al. 2018).

Figure 1.

Location of the municipality of Santa Teresa, southeastern Brazil. Forest remnants from SOS Mata Atlântica (2014).

The predominant vegetation types are montane and sub-montane rainforests (Rizzini 1979), characterized by non-deciduous trees with lead buds without protection against drought (Brasil 1983). Santa Teresa was mostly forested until the arrival of European settlers in 1874. Currently, the municipality has 42% of its original forest cover inside and surrounding three protected areas: the Reserva Biológica Augusto Ruschi (3,598 ha), the Estação Biológica de Santa Lúcia (440 ha), and the Parque Natural de São Lourenço (22 ha) (SOS Mata Atlântica and Inpe 2013). Outside these protected areas, forest remnants are in private properties and mostly restricted to hilltops while the valleys are dominated by different types of human-modified matrix (e.g., coffee plantations, Eucalyptus spp. plantations, abandoned pastures, and settlements; Ferreira et al. 2016).

The climate of Santa Teresa is classified as oceanic climate without dry season and with temperate summer (Cfb) according to Köppen classification (Alvares et al. 2013). Mean annual precipitation is 1,868 mm with highest rainfall in November and lowest in June, when the mean rainfall is less than 60 mm (Mendes and Padovan 2000). Mean annual temperature is 20 °C (range: 14.3–26.2 °C, Thomaz and Monteiro 1997).

Data sampling

The species list presented in this study has been compiled in part using field surveys conducted by the authors from 2006 to 2019, and also through the evaluation of specimens in zoological collections (see Appendix I) and a literature review.

During field surveys, we conducted intensive sampling across Santa Teresa using audio and visual searches inside bromeliads, in the leaf litter, and in water bodies (see Dodd 2010). We released easily identified and extensively vouchered (> 30 specimens) species but took those species with more complex identification back to laboratory. To do this, we kept amphibians in moist plastic tubes or plastic bags to prevent dehydration. Some specimens were euthanized by ventral application of 7.5% to 20% benzocaine, preserved using 10% formalin and then transferred to 70% ethanol (American and Veterinary Medical Association 2013, CEBEA/CFMV 2013).

We also reviewed the literature and compiled records of amphibians for Santa Teresa. In addition, we examined specimens deposited in the following institutions: Coleção de Anfíbios Célio F. B. Haddad (CFBH), Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP); Museu de Biologia Mello Leitão (MBML), Instituto Nacional da Mata Atlântica (INMA); Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG); Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (MNRJ); Museu de Zoologia Prof. Adão José Cardoso (ZUEC), Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP); Museu de Zoologia, Universidade de São Paulo (MZUSP); and Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (USNM) (see Appendix I). We followed Frost (2019) for taxonomic arrangements.

Results

We recorded 108 amphibian species for Santa Teresa, of which 106 (98%) belong to Anura (16 families and 41 genera) and two (2%) to Gymnophiona (one family and one genus) (Table 1; Figure 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). The most represented families were Hylidae with 47 species (43%), Brachycephalidae with 11 species (10%), and Leptodactylidae with 10 species (9%). Santa Teresa is currently the type locality for 23 species (20%) (Table 1). So far, four species (3%) are only found in Santa Teresa such as Crossodactylodesizecksohni, Crossodactylustimbuhy, Ischnocnemacolibri and Ischnocnemaepipeda. The species density of Santa Teresa is 0.16 species per km2 (i.e., 108 species/683 km2).

Table 1.

Amphibian species of Santa Teresa municipality, Espírito Santo state, Southeastern Brazil. An asterisk * indicates a taxonomic change.

| Species by Family | Type locality | Our study | Almeida et al. 2011 | Rödder et al. 2007 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AROMOBATIDAE | ||||

| Allobatescapixaba (Lutz, 1925) | X | X | X* | |

| BRACHYCEPHALIDAE | ||||

| Brachycephalusalipioi Pombal & Gasparini, 2006 | X | X | – | |

| Brachycephalus aff. didactylus | X | – | – | |

| Ischnocnemaabdita Canedo & Pimenta, 2010 | X | X | X | – |

| Ischnocnemacolibri Taucce, Canedo, Parreiras, Drummond, Nogueira-Costa & Haddad, 2018 | X | X | – | – |

| Ischnocnemaepipeda (Heyer, 1984) | X | X | X | X |

| Ischnocnema aff. guentheri | X | X* | X* | |

| Ischnocnemacf.nasuta (Lutz, 1925) | X | X* | X* | |

| Ischnocnemaoea (Heyer, 1984) | X | X | X | X |

| Ischnocnemaaff.parva sp. 1 | X | X* | X* | |

| Ischnocnemaaff.parva sp. 2 | X | – | – | |

| Ischnocnemaverrucosa Reinhardt & Lütken, 1862 | X | X | X | |

| BUFONIDAE | ||||

| Dendrophryniscuscarvalhoi Izecksohn, 1994 | X | X | X | X |

| Rhinellacrucifer (Wied-Neuwied, 1821) | X | X | X | |

| Rhinellagranulosa (Spix, 1824) | X | X | X | |

| Rhinelladiptycha (Cope, 1862) | X | X | X | |

| CENTROLENIDAE | ||||

| Vitreorana aff. eurygnatha | X | X* | X* | |

| Vitreoranauranoscopa (Müller, 1924) | X | X | X | |

| CERATOPHRYIDAE | ||||

| Ceratophrysaurita (Raddi, 1823) | X | X | X* | |

| CRAUGASTORIDAE | ||||

| Euparkerellatridactyla Izecksohn, 1988 | X | X | X | X |

| Haddadusbinotatus (Spix, 1824) | X | X | X | |

| CYCLORAMPHIDAE | ||||

| Cycloramphusfuliginosus Tschudi, 1838 | X | X | X | |

| Thoropa aff. lutzi | X | X* | – | |

| Thoropamiliaris (Spix, 1824) | X | X | X | |

| Thoropapetropolitana (Wandolleck, 1907) | X | X | – | |

| Zachaenuscarvalhoi Izecksohn, 1983 | X | X | X | X |

| ELEUTHERODACTYLIDAE | ||||

| Adelophryneglandulata Lourenço-de-Moraes, Ferreira, Fouquet & Bastos, 2014 | X | X | X* | – |

| HEMIPHRACTIDAE | ||||

| Fritziana aff. fissilis | X | X* | X* | |

| Fritzianatonimi Walker, Gasparini, Haddad, 2016 | X | X | X* | X* |

| Gastrothecaalbolineata (Lutz & Lutz, 1939) | X | X | – | |

| Gastrothecaernestoi Miranda-Ribeiro, 1920 | X | – | – | |

| Gastrothecamegacephala Izecksohn, Carvalho-e-Silva & Peixoto, 2009 | X | – | – | |

| HYLIDAE | ||||

| Aparasphenodonbrunoi Miranda-Ribeiro, 1920 | X | – | X | |

| Aplastodiscuscavicola (Cruz & Peixoto, 1985) | X | X | X | X |

| Aplastodiscus aff. eugenioi | X | – | – | |

| Aplastodiscusweygoldti (Cruz & Peixoto, 1987) | X | X | X | X |

| Boanaalbomarginata (Spix, 1824) | X | X | X | |

| Boanaalbopunctata (Spix, 1824) | X | X | X | |

| Boanacrepitans (Wied-Neuwied, 1824) | X | X | X | |

| Boanafaber (Wied-Neuwied, 1821) | X | X | X | |

| Boanapardalis (Spix, 1824) | X | X | X | |

| Boanapolytaenia (Cope, 1870) | X | X | – | |

| Boanasemilineata (Spix, 1824) | X | X | X | |

| Bokermannohylacaramaschii (Napoli, 2005) | X | X | X | X |

| Dendropsophusberthalutzae (Bokermann, 1962) | X | X | X | |

| Dendropsophusbipunctatus (Spix, 1824) | X | X | X | |

| Dendropsophusbranneri (Cochran, 1948) | X | X | X | |

| Dendropsophusbromeliaceus Ferreira, Faivovich, Beard & Pombal, 2015 | X | X | – | – |

| Dendropsophusdecipiens (Lutz, 1925) | X | X | X | |

| Dendropsophuselegans (Wied-Neuwied, 1824) | X | X | X | |

| Dendropsophusgiesleri (Mertens, 1950) | X | X | X | |

| Dendropsophushaddadi (Bastos & Pombal, 1996) | X | X | X | |

| Dendropsophusmicrops (Peters, 1872) | X | X | X | |

| Dendropsophusminutus (Peters, 1872) | X | X | X | |

| Dendropsophusruschii (Weygoldt & Peixoto, 1987) | X | X | X | |

| Dendropsophusseniculus (Cope, 1868) | X | X | X | |

| Itapotihylalangsdorffii (Duméril & Bibron, 1841) | X | X | X | |

| Ololygonarduous (Peixoto, 2002) | X | X | X | X |

| Ololygonargyreornata (Miranda-Ribeiro, 1926) | X | X | X | |

| Ololygoncf.flavoguttata (Lutz & Lutz, 1939) | X | – | – | |

| Ololygon aff. heyeri | X | – | – | |

| Ololygonheyeri Peixoto & Weygoldt, 1986 | X | X | X | X |

| Ololygonkautskyi Carvalho-e-Silva & Peixoto, 1991 | X | X | X | |

| Phasmahylaexilis (Cruz, 1980) | X | X | X | X |

| Phrynomedusamarginata (Izecksohn & Cruz, 1976) | X | X | X | X |

| Phyllodyteskautskyi Peixoto & Cruz, 1988 | X | – | – | |

| Phyllodytesluteolus (Wied-Neuwied, 1824) | X | X | X | |

| Phyllodytes aff. luteolus | X | – | – | |

| Phyllomedusaburmeisteri Boulenger, 1882 | X | X | X | |

| Pithecopus aff. rohdei | X | X* | X* | |

| Scinaxalter (Lutz, 1973) | X | X | X | |

| Scinaxcuspidatus (Lutz, 1925) | X | X | X | |

| Scinaxeurydice (Bokermann, 1968) | X | X | X* | |

| Scinaxfuscovarius (Lutz, 1925) | X | X | X | |

| Scinaxhayii (Barbour, 1909) | X | X | X* | |

| Scinax aff. perereca | X | – | – | |

| Scinaxcf.x-signatus (Spix, 1824) | X | X | X | |

| Trachycephalusmesophaeus (Hensel, 1867) | X | X | X | |

| Trachycephalusnigromaculatus Tschudi, 1838 | X | X | X | |

| HYLODIDAE | ||||

| Crossodactylus aff. gaudichaudii | X | X | X* | |

| Crossodactylustimbuhy Pimenta, Cruz & Caramaschi, 2014 | X | X | X* | X* |

| Hylodescf.babax Heyer, 1982 | X | X* | X* | |

| Hylodeslateristrigatus (Baumann, 1912) | X | X | X | |

| Megaelosiaapuana Pombal, Prado & Canedo, 2003 | X | X | X* | |

| LEPTODACTYLIDAE | ||||

| Crossodactylodesbokermanni Peixoto, 1983 | X | X | X | X |

| Crossodactylodesizecksohni Peixoto, 1983 | X | X | X | X |

| Leptodactyluscupreus Caramaschi, Feio & São Pedro, 2008 | X | X | – | |

| Leptodactylusfuscus (Schneider, 1799) | X | X | X | |

| Leptodactylusaff.latrans (Steffen, 1815) | X | X* | X* | |

| Leptodactylus aff. spixi | X | X* | X* | |

| Physalaemuscrombiei Heyer & Wolf, 1989 | X | X | X | X |

| Physalaemuscuvieri Fitzinger, 1826 | X | X | X | |

| Physalaemusmaculiventris (Lutz, 1925) | X | X | – | |

| Physalaemuscf.olfersii (Lichtenstein & Martens, 1856) | X | X* | X* | |

| MICROHYLIDAE | ||||

| Chiasmocleiscapixaba Cruz, Caramaschi & Izecksohn, 1997 | X | – | – | |

| Chiasmocleisschubarti Bokermann, 1952 | X | – | X | |

| Myersiellamicrops (Duméril & Bibron, 1841) | X | X | X | |

| ODONTOPHRYNIDAE | ||||

| Macrogenioglottusalipioi Carvalho, 1946 | X | X | X | |

| Proceratophrysboiei (Wied-Neuwied, 1824) | X | X | X | |

| Proceratophryslaticeps Izecksohn & Peixoto, 1981 | X | X | X | |

| Proceratophrysmoehringi Weygoldt & Peixoto, 1985 | X | X | X | X |

| Proceratophryspaviotii Cruz, Prado & Izecksohn, 2005 | X | X | X | X |

| Proceratophrysphyllostomus Izecksohn, Cruz & Peixoto, 1999 | X | X | X | |

| Proceratophrysschirchi (Miranda-Ribeiro, 1937) | X | X | X | |

| PIPIDAE | ||||

| Pipa aff. carvalhoi | X | X* | X* | |

| RANIDAE | ||||

| Lithobatescatesbeianus (Shaw, 1802) | X | – | – | |

| SIPHONOPIDAE | ||||

| Siphonopsannulatus (Mikan, 1822) | X | – | – | |

| Siphonopshardyi Boulenger, 1888 | X | – | – | |

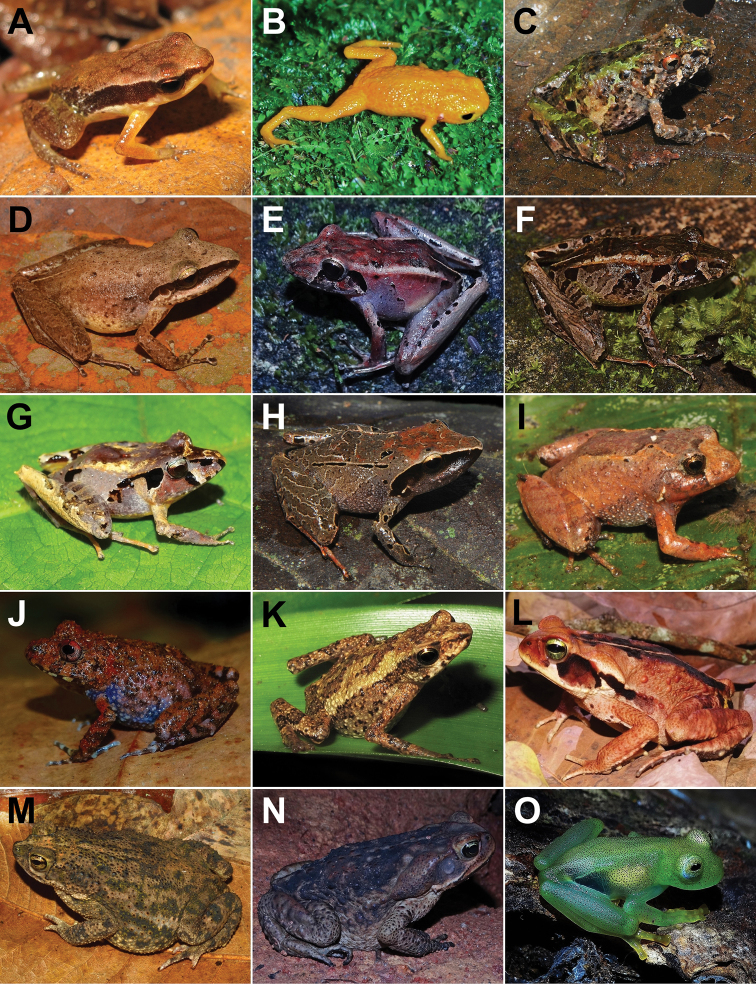

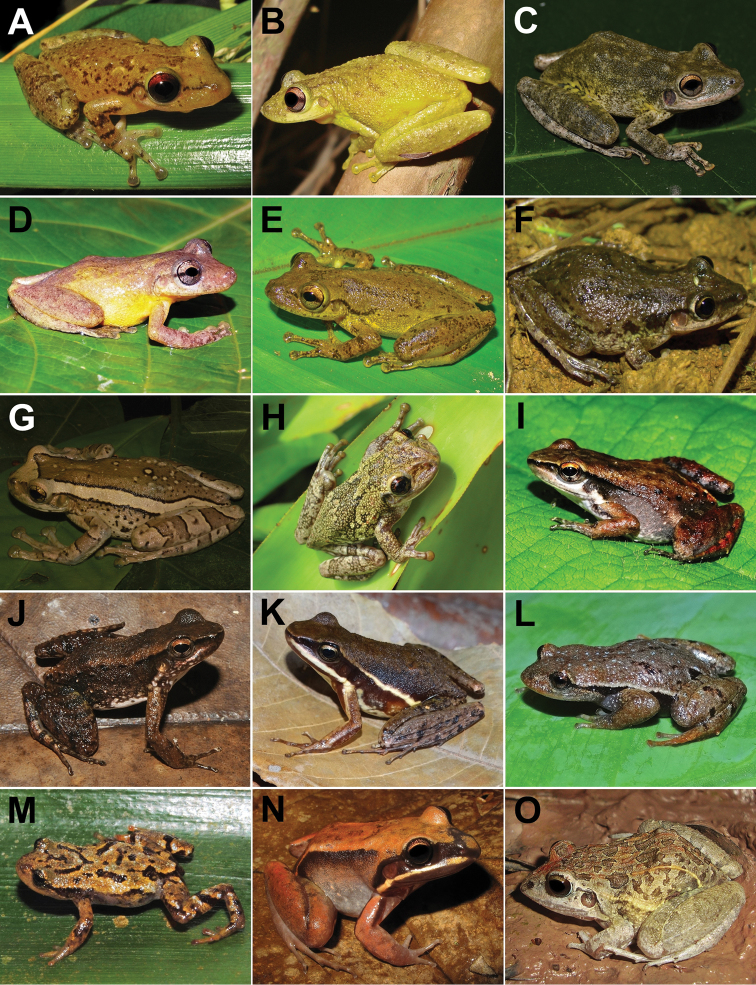

Figure 2.

Amphibians from Santa Teresa: AAllobatescapixabaBBrachycephalusalipioiCIschnocnemaabditaDIschnocnemacolibriEIschnocnemacf.nasutaFIschnocnemaaff.guentheriGIschnocnemaoeaHIschnocnemagr.parva sp. new 1 IIschnocnemagr.parva sp. new 2 JIschnocnemaverrucosaKDendrophryniscuscarvalhoiLRhinellacruciferMRhinellagranulosaNRhinelladiptychaOVitreoranaaff.eurygnatha. Photographs by JFR Tonini (A), CN Fraga (B), RB Ferreira (C, D, H, I, K), AT Mônico (E, G, J, K, L, M, N, O), T Silva-Soares (F).

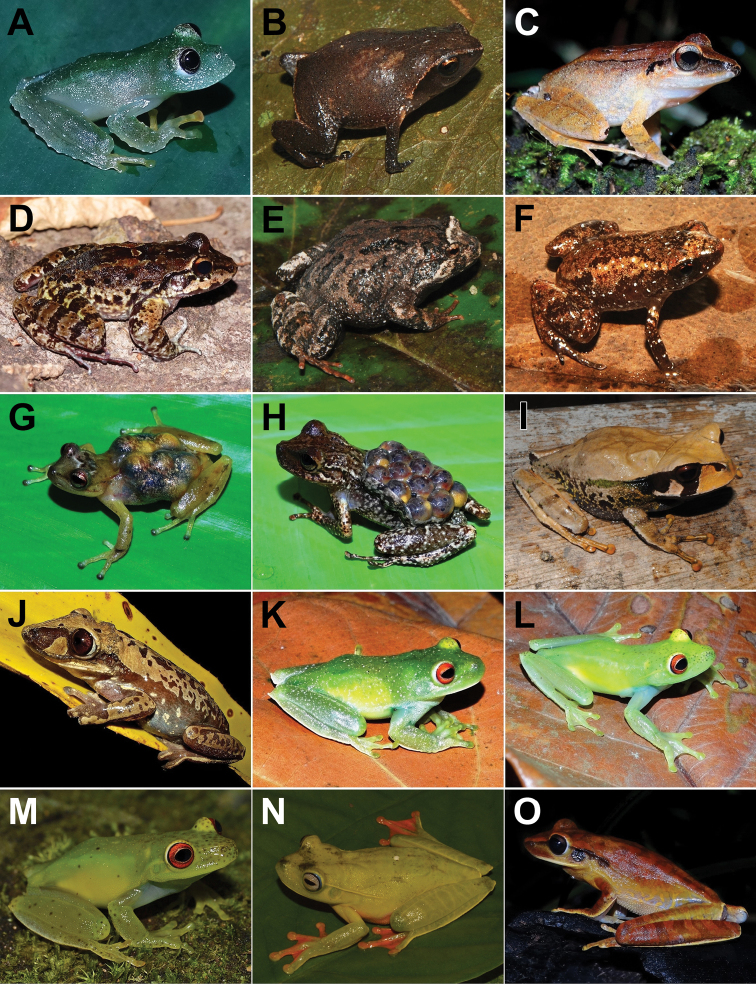

Figure 3.

Amphibians from Santa Teresa: AVitreoranauranoscopaBEuparkerellatridactylaCHaddadusbinotatusDThoropamiliarisEZachaenuscarvalhoiFAdelophryneglandulataGFritzianaaff.fissilisHFritzianatonimiIGastrothecamegacephalaJAparasphenodonbrunoiKAplastodiscuscavicolaLAplastodiscusaff.eugenioiMAplastodiscusweygoldtiNBoanaalbomarginataOBoanaalbopunctata. Photographs by AT Mônico (A, C, D, G, H, K, L, O), RB Ferreira (B, E, F, I, N), C Zocca (J), T Silva-Soares (M).

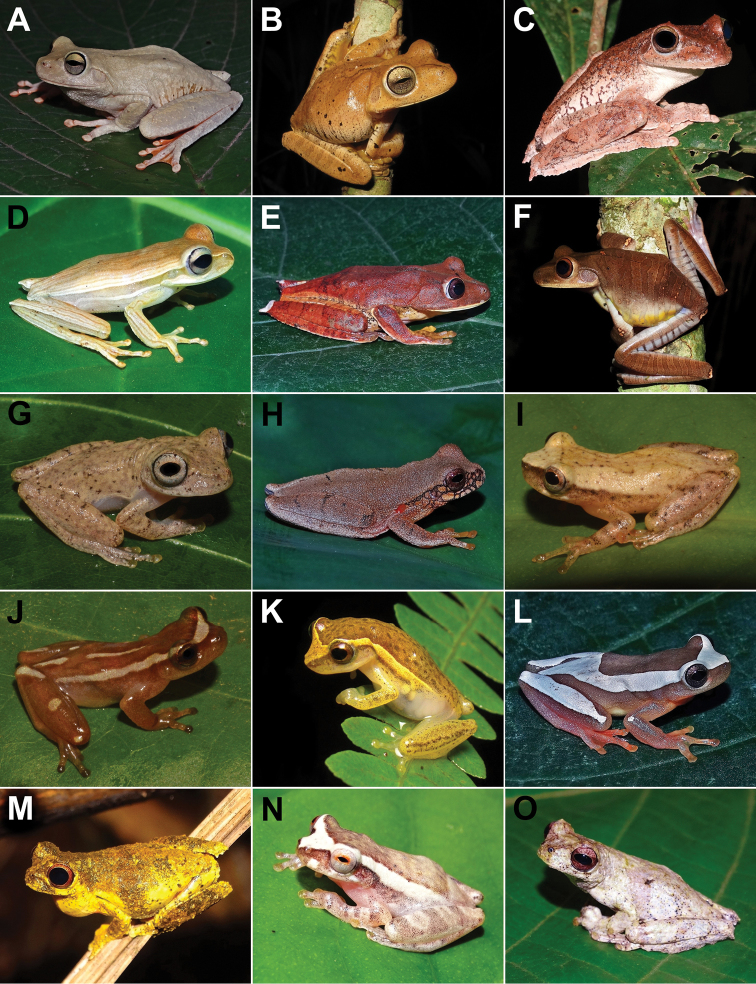

Figure 4.

Amphibians from Santa Teresa: ABoanacrepitansBBoanafaberCBoanapardalisDBoanapolytaeniaEBoanasemilineataFBokermannohylacaramaschiiGDendropsophusberthalutzaeHDendropsophusbipunctatusIDendropsophusbranneriJDendropsophusbromeliaceusKDendropsophusdecipiensLDendropsophuselegansMDendropsophusgiesleriNDendropsophushaddadiODendropsophusmicrops. Photographs by AT Mônico (A, C, D, E, F, H, L, M, N, O), RB Ferreira (B, G, I, J), ET Silva (K).

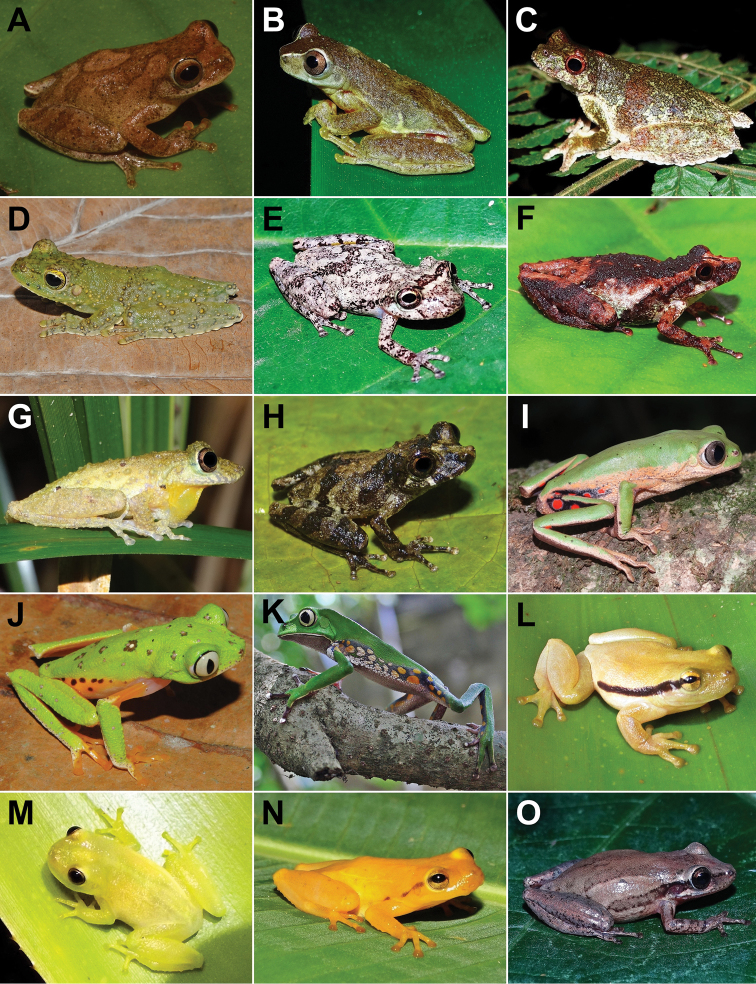

Figure 5.

Amphibians from Santa Teresa: ADendropsophusminutusBDendropsophusruschiiCDendropsophusseniculusDItapotihylalangsdorffiiEOlolygonarduousFOlolygonargyreornataGOlolygonheyeriHOlolygonkautskyiIPithecopusaff.rohdeiJPhasmahylaexilisKPhyllomedusaburmeisteriLPhyllodyteskautskyiMPhyllodytesluteolusNPhyllodytesaff.luteolusOScinaxalter. Photographs by RB Ferreira (A, D, J), AT Mônico (B, C, E, F, G, I, K, N, O), T Silva-Soares (H), CZ Zocca (L, M).

Figure 6.

Amphibians from Santa Teresa: AScinaxcuspidatusBScinaxeurydiceCScinaxfuscovariusDScinaxhayiiEScinaxaff.pererecaFScinaxcf.x-signatusGTrachycephalusmesophaeusHTrachycephalusnigromaculatusICrossodactylusaff.gaudichaudiiJCrossodactylustimbuhyKHylodeslateristrigatusLCrossodactylodesbokermanniMCrossodactylodesizecksohniNLeptodactyluscupreusOLeptodactylusfuscus. Photographs by ET Silva (A, E, F), CZ Zocca (B, O), T Silva-Soares (C), AT Mônico (D, I, K, L), RB Ferreira (G, H, J, M), JFR Tonini (N).

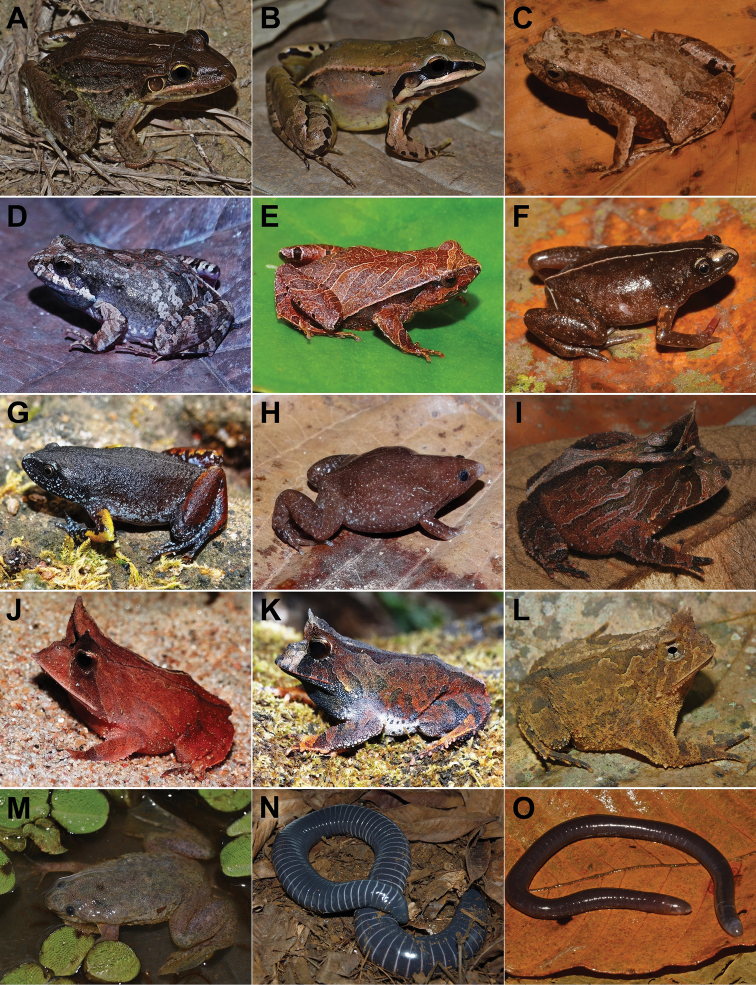

Figure 7.

Amphibians from Santa Teresa: ALeptodactylusaff.latransBLeptodactylusaff.spixiCPhysalaemuscrombieiDPhysalaemuscuvieriEPhysalaemusmaculiventrisFChiasmocleiscapixabaGChiasmocleisschubartiHMyersiellamicropsIProceratophrysboieiJProceratophryslaticepsKProceratophryspaviotiiLProceratophrysschirchiMPipaaff.carvalhoiNSiphonopsannulatusOSiphonopshardyi. Photographs by T Silva-Soares (A, B, L, M, N), AT Mônico (C, D, E, G, H, J, K), RB Ferreira (F, I, O).

Compared to previous anuran lists for Santa Teresa, we added 14 species, removed 17 previously reported species, and re-determined 14 species based on recent taxonomic rearrangements. Out of the 14 added species, 11 (79%) were first recorded during our fieldwork and specimen examination, two (14%) records were from the literature, and one (7%) new record was from pers. comm. (Gastrothecaernestoi; MT Rodrigues, field number MTR 34695).

Fourteen species classified to morphotypes are new species, such as Aplastodiscusaff.eugenioi (M Mongin, pers. comm.), Brachycephalusaff.didactylus (TSS, in. prep.), Crossodactylusaff.gaudichaudii (R Montesinos, in. prep.), Fritzianaaff.fissilis (RBF, pers. obs.), Ischnocnemaaff.parva sp. 1 (CAG Cruz, in. prep.), Ischnocnemaaff.parva sp. 2 (TSS, in. prep.), Leptodactylusaff.spixi (L Nascimento, in. prep.), Ololygonaff.heyeri (J Lacerda, pers. comm.), Phyllodytesaff.luteolus (ATM, in. prep.), Pipaaff.carvalhoi (PV Scherrer, in. prep.), Pithecopusaff.rohdei (D Baêta, pers. comm.), Scinaxaff.perereca (TSS, pers. comm.), Thoropaaff.lutzi (CL Assis, pers. comm.), and Vitreoranaaff.eurygnatha (R Pontes, in. prep.).

Discussion

The current number of 106 anuran species for Santa Teresa is remarkable, and represents 78% of the 136 species listed for Espírito Santo state (Almeida et al. 2011, Rossa-Feres et al. 2017), 10% of the 1,080 species listed for Brazil (Segalla et al. 2016), and 1.5% of the 7,068 species listed worldwide (AmphibiaWeb 2019). To date, the species density (i.e., 0.16 species per km2) is one of the highest in the world at regional scale. For instance, Yasuní National Park in Ecuador has 0.015 species per km2 (i.e., 150 species/9,820 km2; Bass et al. 2010); Tambopata in southern Peru has 0.06 species per km2 (i.e., 99 species/1,600 km2; Doan and Arriaga 2002); Iquitos region of northern Loreto in Peru has 0.012 species per km2 (i.e., 141 species/11,310 km2; IUCN 2008, Rodríguez and Duellman 1994); and Leticia in Colombia has 0.13 species per km2 (i.e., 123 species/927 km2; Lynch 2005). Several other localities across the Atlantic Forest also have remarkable amphibian richness at local scales. For example, Reserva Biológica de Paranapiacaba in Sao Paulo state has 20.5 species per km2 (69 species/3.36 km2; Verdade et al. 2009); Fazenda Vista Bela in Bahia state has 7.3 species per km2 (34 species/4.65 km2; Silvano and Pimenta 2003); and Reserva Particular do Patrimônio Natural Serra Bonita has 4 species per km2 (80 species/20 km2; Dias et al. 2014). We acknowledge that amphibian richness per area represents just a first approximation for practical spatial comparisons and that the lack of adequate surveys in more unexplored diverse regions (e.g., Indonesia, New Guinea, and the Congo Basin) may reveal remarkable amphibian richness. So far, Brazil’s Atlantic Forest and the northwest Amazon are considered the world’s greatest amphibian diversity on a landscape scale (Young et al. 2004, Bass et al. 2010).

The two species of Gymnophiona (Siphonopsannulatus and S.hardyi) were found during our fieldwork but have been reported previously for Santa Teresa (Caramaschi et al. 2004, Maciel et al. 2009). The former has a wide distribution in South America from Colombia to Argentina (Frost 2018). The latter has a more restricted distribution in southeastern of Brazil (Maciel et al. 2009, Frost 2018). Caecilians are difficult to sample due to the subterranean or aquatic habits (Oommen et al. 2000, Maciel and Hoogmoed 2011). Although amphibians are dramatically declining (Stuart et al. 2004), the conservation status of caecilians is largely unknown due to the lack of information on their biology, ecology and natural history (Wilkinson and Nussbaum 1999, Oommen et al. 2000, Gower and Wilkinson 2005). It is likely more species of caecilians will be recorded in Santa Teresa if the use of sampling methods specific for these taxa is applied in the field.

Our fieldwork since 2005 in Santa Teresa has made notable contributions toward the knowledge of local amphibians. It has resulted in the description of three new species for the municipality (i.e., Adelophryneglandulata in Lourenço-de-Moraes, Ferreira, Fouquet, Bastos 2014, Dendropsophusbromeliaceus in Ferreira, Faivovich, Beard, Pombal 2015, and Ischnocnemacolibri in Taucce, Canedo, Parreiras, Drummond, Nogueira-Costa, Haddad 2018). Furthermore, our fieldwork found individuals of 13 morphospecies that are currently under formal description (i.e., Aplastodiscus aff. eugenioi, Brachycephalusaff.didactylus, Crossodactylusaff.gaudichaudii, Fritziana aff. fissilis, Ischnocnemaaff.parva sp. 1, Ischnocnemaaff.parva sp. 2, Leptodactylusaff.spixi, Ololygonaff.heyeri, Phyllodytesaff.luteolus, Pipaaff.carvalhoi, Pithecopus aff. rohdei, Scinaxaff.perereca, and Vitreoranaaff.eurygnatha). The discovery of new species, morphospecies, and new records for Santa Teresa may be due to our sampling in remote forested areas and rocky outcrops through both visual bromeliad surveys and active leaf-litter searches (Ferreira et al. 2016).

Our species list resolved some differences between the previous species lists of Santa Teresa, which had disagreements on 11 species (e.g., Rödder et al. 2007, Almeida et al. 2011). We confirmed that Chiasmocleisschubarti occurs in Santa Teresa based on several individuals sampled in the Reserva Biológica Augusto Ruschi, whereas Almeida et al. (2011) challenged previous records of this species listed in Cruz et al. (1997) and Rödder et al. (2007). We also confirmed the presence of Aparasphenodonbrunoi and Trachycephalusnigromaculatus reported in Santa Teresa at the buffer zone of the Parque Municipal do Goiapaba-Açu (Ramos and Gasparini 2004). Almeida et al. (2011) challenged the record of Rhinellahoogmoedi referring to the species as Rhinellagr.margaritifer, because the former species was not mentioned in Rödder et al. (2007). We agree with Almeida et al. (2011) regarding the exclusion of several species from Rödder et al. (2007), such as Bokermannohylaaff.nanuzae (MBML 4528 corresponds to B.caramaschii), Dendrophryniscus sp. (MBML 3841 corresponds to D.carvalhoi), Ischnocnemacf.juipoca (MBML 5737 corresponds to I.abdita), I.lactea (MBML 1143 corresponds to I.abdita), Physalaemusaguirrei (MBML 2803-04 correspond to P.cf.olfersii), and Proceratophrysappendiculata (MBML 1154 corresponds to P.schirchii). Rödder et al. (2007) and Almeida et al. (2011) listed Leptodactylusnatalensis for Santa Teresa but the voucher specimens (MBML 3909-10) were misidentified and actually refer to individuals of L.aff.spixi. Rödder et al. (2007) listed Allobatescf.olfersioides following Verdade and Rodrigues (2007) who placed A.capixaba as synonym of A.olfersioides. Studies on Allobates indicate A.capixaba is a valid taxon (e.g., Bokermann 1967; Forti et al. 2017), which agrees with Almeida et al. (2011). Fieldwork should be conducted in the vicinities of Santa Teresa to confirm the presence of Brachycephalusalipioi. This species has not been found in Santa Teresa since 1952 when the municipality was larger than it is today (Pombal and Gasparini 2006).

The wide elevational range of Santa Teresa (~120–1099 m a.s.l.) partially explains the high richness of amphibian species. Species typical of both Atlantic Forest lowlands (e.g., Allobatescapixaba, Chiasmocleisschubarti, C.capixaba, Dendropsophusbipunctatus, Ololygonargyreornata) and highlands (e.g., Aplastodiscuscavicola, Bokermannohylacaramaschii, Dendropsophusruschii) occur in Santa Teresa, which suggest that the elevational gradient influences species composition. The high amphibian diversity also may be related to edaphic and topographic heterogeneity, which is known to cause speciation in many Atlantic Forest species occurring in mountainous areas (Carnaval et al. 2014). The high altitude and proximity to the Atlantic Ocean favors frequent orographic rain, which contribute to the meeting the reproductive requirements of amphibians. It is worth highlighting that Santa Teresa is one of the most sampled regions for amphibians in the Atlantic Forest (Rödder et al. 2007, Almeida et al. 2011, Zocca et al. 2014, Ferreira et al. 2016). About 3,800 anuran specimens collected in Santa Teresa were found housed in Brazilian collections (ET Silva, pers. obs.). This high sampling effort, which is comparable to only a few localities in the Atlantic Forest, may also account for such high species richness.

Conservation remarks

Amphibians from Santa Teresa have faced several anthropogenic disturbances over the last couple of decades. The first report on amphibian declines for Santa Teresa was in 1989 (see Weygoldt 1989). During long-term sporadic samplings (i.e., 1975 and 1988), Weygoldt (1989) reported the decline and possible disappearances of eight species (updated taxonomy: Allobatescapixaba, Crossodactylusaff.gaudichaudii, C.timbuhy, Cycloramphusfuliginosus, Hylodeslateristrigatus, H.cf.babax, Phasmahylaexilis, and Vitreoranaaff.eurygnatha). To our knowledge, Cycloramphusfuliginosus and Hylodescf.babax have not been recorded after Weygoldt (1989). Additionally, Thoropapetropolitana, a frog not mentioned by Weygoldt (1989) has disappeared with no recent records along its entire range (Haddad et al. 2016). Several potential causes of these declines were mentioned by Weygoldt (1989), such as pollution (acid rain and pesticides), long-term climatic changes, and epidemic diseases. Weygoldt (1986) mentioned that Crossodactyluscf.dispar (currently C.timbuhy) was rare in Santa Teresa and later reported its decline. However, during our surveys we easily found this species on creeks across Santa Teresa. We cannot assess whether species declines are actually happening in Santa Teresa because only long-term and species-specific studies can precisely understand population trends.

Over the decades, we have noted population disappearances of anurans in Santa Teresa. The construction of condominiums and vacation ranches has intensified over the last decade and consequently increased deforestation of primary forest. We have also observed the expansion of the non-native Eucalyptus spp. plantations near primary and secondary forests and the replacement of coffee plantations. Another unmeasured concern is the increasing record of morphological anuran deformities, which is likely a result of pesticides used on crops (e.g., Mônico et al. 2016), including inside the buffer zone of the largest forest reserve (i.e., Reserva Biológica Augusto Ruschi; pers. obs.). The report of the invasive frog, Lithobatescatesbeianus, in Santa Teresa (see Ferreira and Lima 2012) should be further evaluated to monitor its establishment, and possible spread and impacts. We emphasize the need to sample the surroundings of the nearby breeding farms of L.catesbeianus. Studies have shown that non-native L.catesbeianus can be voracious predators of native anurans and vectors of diseases (Schloegel et al. 2010, Silva et al. 2011, Boelter et al. 2012).

The landscape configuration of Santa Teresa does not safeguard the maintenance of amphibian reproduction outside protected reserves because forests on private properties are mostly restricted to hilltops and non-natural matrix habitats occupy most valleys. Because water-body breeding species migrate toward reproductive habitats in the valleys, these species face severe threats, such as the risk of predation and desiccation (Becker et al. 2007, Ferreira et al. 2016). In addition, pollution of creeks and streams further strengthen conservation concern of lotic body breeders. We reinforce the need of studies focused on the threats amphibians are facing in the region to provide knowledge for conservationists and reserves managers to safeguard the local diversity.

Santa Teresa is an important hotspot for amphibian conservation due to its high richness and number of endemic species. The discovery of several new species further emphasizes the importance of this mountainous region for amphibian conservation. Even though Santa Teresa and its surrounding areas in southeastern Brazil are one of the most sampled regions in the Atlantic Forest, the region still harbors numerous remote areas that have not yet been sampled for frogs (e.g., Almeida et al. 2011). Forests on private properties are also important for preserving amphibian diversity in the area (Ferreira et al. 2016). In addition, private properties may function as forest corridors for dispersing and migrating species. We suggest that a program to stimulate the creation of private-owner reserves and ecotourism activities should be implemented in this region. Finally, we have been developing outreach activities (e.g., Bromeligenous Project) with the local farmers, aiming to minimize the anthropogenic effects on anurans. Nevertheless, there is a strong need for a long-term outreach program in the local schools and in the farmlands to protect these forest areas in the future.

Acknowledgements

We dedicated this manuscript to Rogério L Teixeira who was born and raised in Santa Teresa and dedicated decades sampling frogs and mentoring herpetologists. We thank Bromeligenous Project for field support; landowners for allowing access to their properties; Instituto Nacional da Mata Atlântica for logistic support. We are grateful to Cecilia Waichert, Francys Lacchine, Gustavo Milanezi, Jandyra Zocca Zandomenico, Juliano Saich, Lamara P Barbosa, Namany Lourpen, Paulo R Jesus, Randerson LB Ferreira for field sampling. We especially thank Carlos A Cruz, Clarissa Canedo, Clodoaldo L Assis, Délio Baeta, Gustavo Prado, João V Lacerda, Juliana Kirchmeyer, Juliana Peres, Leo Malagoli, Marcele Mongin, Marco A Peixoto, Miguel Trefault Rodrigues, Paulo V Scherrer, Pedro Taucce, Rafael Pontes, Raquel Montesinos, and Victor Dill for discussions on species identification. Sampling permits were issued by Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio, permits 28607, 50402, and 63575) and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC-USU, permit 2002). RBF (0823/FCLF (001/1774502), and CZZ (001/1700071) thank Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) for scholarships. RBF, ATM, ETS and TSS thank Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq: 430195/2018, 304374/2016-4, 141569/2014-0, and 454789/2015-7) for scholarships. JFRT thanks CAPES/Science without Borders and David Rockefeller Center for Latin Studies/Harvard University for scholarships. This research was supported by the Utah Agricultural Experiment Station, Utah State University, and approved as journal paper number 9217 and by Harvard Open Access Equity Fund (HOPE).

Appendix I

Vouchers of examined specimens

Adelophryneglandulata (MBML 9560), Allobatescapixaba (MZUSP 53559), Aplastodiscuscavicola (MBML 9620), Aplastodiscusaff.eugenioi (MBML 7901), Aplastodiscusweygoldti (MBML 9540), Boanaalbomarginata (MBML 9610), Boanaalbopunctata (MBML 9673), Boanacrepitans (MBML 9624), Boanafaber (MBML 9576), Boanapardalis (MBML 9577), Boanasemilineata (MBML 9554), Bokermannohylacaramaschii (MBML 9552), Brachycephalusalipioi (MNRJ 25405), Ceratophrysaurita (MBML 591), Chiasmocleiscapixaba (MBML 2644), Chiasmocleisschubarti (MBML 9599), Crossodactylodesbokermanni (MBML 3984), Crossodactylodesizecksohni (MBML 768), Crossodactylusaff.gaudichaudii (MBML 15), Crossodactylustimbuhy (MBML 13), Cycloramphusfuliginosus (USNM 200441), Dendrophryniscuscarvalhoi (MBML 8722), Dendropsophusberthalutzae (MBML 8589), Dendropsophusbipunctatus (MBML 2446), Dendropsophusbranneri (MBML 9611), Dendropsophusbromeliaceus (MBML 7712), Dendropsophusdecipiens (MBML 9590), Dendropsophuselegans (MBML 9543), Dendropsophusgiesleri (MBML 8795), Dendropsophushaddadi (MBML 8775), Dendropsophusmicrops (MNRJ 30445), Dendropsophusminutus (MBML 9593), Dendropsophusruschii (CFBH 37010), Dendropsophusseniculus (MBML 9591), Euparkerellatridactyla (MBML 7585), Fritzianaaff.fissilis (MBML 46), Fritzianatonimi (MBML 8604), Gastrothecaalbolineata (MBML 47), Gastrothecamegacephala (MBML 9672), Haddadusbinotatus (MBML 9621), Hylodescf.babax (USNM 222553), Hylodeslateristrigatus (MBML 9595), Ischnocnemaabdita (MBML 1143), Ischnocnemacolibri (MBML 10568-10572), Ischnocnemaaff.guentheri (MBML 4534), Ischnocnemacf.nasuta (MBML 4667), Ischnocnemaoea (MBML 8705), Ischnocnemaaff.parva sp. 1 (MBML 9550), Ischnocnemaverrucosa (MBML 9569), Itapotihylalangsdorffii (MBML 8585), Leptodactyluscupreus (MBML 6845), Leptodactylusfuscus (MBML 6003), Leptodactylusaff.latrans (MBML 2077), Leptodactylusaff.spixi (MBML 2439), Macrogenioglottusalipioi (MBML 93), Myersiellamicrops (MBML 9561), Ololygonarduous (MBML 9657), Ololygonargyreornata (MBML 2828), Ololygoncf.flavoguttata (MBML 9649), Ololygonheyeri (MBML 8581), Ololygonkautskyi (MBML 9594), Phasmahylaexilis (MNRJ 4120), Phrynomedusamarginata (MNRJ 46881), Phyllodytesluteolus (MBML 6785), Phyllodytesaff.luteolus (MBML 9658), Phyllomedusaburmeisteri (MBML 9581), Physalaemuscrombiei (MBML 9542), Physalaemuscuvieri (MBML 9579), Physalaemusmaculiventris (MBML 9567), Physalaemuscf.olfersii (MBML 2803), Pipaaff.carvalhoi (MBML 4519), Pithecopusaff.rohdei (MBML 9580), Proceratophrysboiei (MBML 142), Proceratophryslaticeps (MBML 3905), Proceratophrysmoehringi (MBML 6409), Proceratophryspaviotii (MBML 9585), Proceratophrysphyllostomus (MBML 325), Proceratophrysschirchi (MBML 9677), Rhinellacrucifer (MBML 9575), Rhinellagranulosa (MBML 2573), Rhinelladiptycha (MBML 687), Scinaxalter (MBML 9612), Scinaxcuspidatus (MBML 3594), Scinaxeurydice (MBML 1128), Scinaxfuscovarius (MBML 7820), Scinaxhayii (MBML 4707), Scinaxaff.perereca (MBML 508), Scinaxcf.x-signatus (MBML 4542), Siphonopsannulatus (MBML 8586), Siphonopshardyi (MBML 8909), Thoropaaff.lutzi (MNRJ 1373), Thoropamiliaris (MBML 9571), Thoropapetropolitana (MZUSP 27725), Trachycephalusmesophaeus (MBML 8793), Trachycephalusnigromaculatus (MBML 9213), Vitreoranaaff.eurygnatha (MBML 9678), Vitreoranauranoscopa (MBML 3725), Zachaenuscarvalhoi (MNRJ 84116).

Citation

Ferreira RB, Mônico AT, da Silva ET, Lirio FCF, Zocca C, Mageski MM, Tonini JFR, Beard KH, Duca C, Silva-Soares T (2019) Amphibians of Santa Teresa, Brazil: the hotspot further evaluated. ZooKeys 857: 139–162. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.857.30302

References

- Almeida AP, Gasparini JL, Peloso PLV. (2011) Frogs of the state of Espírito Santo, southeastern Brazil – The need for looking at the coldspots. CheckList 7(4): 542–560. 10.15560/7.4.542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvares CA, Stape JL, Sentelhas PC, Gonçalves JLM, Sparoveck G. (2013) Koppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 22: 711–728. 10.1127/0941-2948/2013/0507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American and Veterinary Medical Association (2013) Guidelines for the euthanasia of animals. AVMA, Schaumberg, IL.

- AmphibiaWeb (2019) University of California, Berkeley, CA. http://amphibiaweb.org [Accessed on 20 May 2019]

- Bass MS, Finer M, Jenkins CN, Kreft H, Cisneros-Heredia DF, McCracken SF, Pitman NCA, English PH, Swing K, Villa G, Fiore AD, Voigt CC, Kunz TH. (2010) Global Conservation Significance of Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park. PloS ONE 5: e8767. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Becker CG, Fonseca CR, Haddad CFB, Batista RF, Prado PI. (2007) Habitat split and the global decline of amphibians. Science 318: 1775–1777. 10.1126/science.1149374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelter RA, Kaefer IL, Both C, Cechin S. (2012) Invasive bullfrogs as predators in a Neotropical assemblage: What frog species do they eat? Animal Biology 62: 397–408. 10.1163/157075612X634111 [DOI]

- Bokermann WCA. (1967) Novas espécies de Phyllobates do leste e sudeste brasileiro (Anura, Dendrobatidae). Revista Brasileira de Biologia 27: 349–353. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil (1983) Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral. Projeto RADAM. V32. Folhas SF23/24 Rio de Janeiro/Vitória, Rio de Janeiro.

- Brown KS Jr, Freitas AVL. (2000) Atlantic Forest butterflies: indicators for landscape conservation. Biotropica 32: 934–956. 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2000.tb00631.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campos FS, Lourenço-de-Moraes R, Llorente GA, Solé M. (2017) Cost-effective conservation of amphibian ecology and evolution. Science Advances 3(6): e1602929. 10.1126/sciadv.1602929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Campos FS, Lourenço-de-Moraes R. (2017) Amphibians from the mountains of the Serra do Mar Coastal Forest, Brazil. Herpetology Notes 10: 547–560. [Google Scholar]

- Caramaschi U, Rodrigues MT, Carvalho-e-Silva SP, Cruz CAG. (2004) Siphonopshardyi IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. http://www.iucnredlist.org [Acessed on 17 April 2009]

- Carnaval AC, Waltari E, Rodrigues MT, Rosauer D, VanDerWal J, Damasceno R, Prates I, Strangas M, Spanos Z, Rivera D, Pie MR, Firkowski CR, Bornschein MR, Ribeiro LF, Moritz C. (2014) Prediction of phylogeographic endemism in an environmentally complex biome. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Biological Science 281: 20141461. 10.1098/rspb.2014.1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carvalho T, Becker CG, Toledo LF. (2017) Historical amphibian declines and extinctions in Brazil linked to chytridiomycosis. Proceedings of the Royal Society Biological Sciences 284: 20162254. 10.1098/rspb.2016.2254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- CEBEA/CFMV CdÉBeB-EA (2013) Guia brasileiro de boas práticas para eutanásia de animais. Conselho Federal de Medicina Veterinária do Brasil, Brasília, 62 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz CAG, Caramaschi U, Izecksohn E. (1997) The genus Chiasmocleis Méhely 1904 (Anura, Microhylidae) in the Atlantic Rain Forest of Brazil, with description of three new species. Alytes 15: 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- Dias I, Medeiros T, Vila Nova M, Solé M. (2014) Amphibians of Serra Bonita, southern Bahia: a new hotpoint within Brazil’s Atlantic Forest hotspot. ZooKeys 449: 105–130. 10.3897/zookeys.449.7494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan TM, Arriaga WA. (2002) Microgeographic variation in species composition of the herpetofaunal communities of Tambopata Region, Peru. Biotropica 34: 101–117. 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2002.tb00246.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd Jr CK. (2010) Diversity and similarity. In: Dodd Jr CK. (Ed.) Amphibian Ecology and Conservation.A Handbook of Techniques, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 321–337.

- Ferreira RB, Faivovich J, Beard KH, Pombal JP. (2015) The first bromeligenous species of Dendropsophus (Anura, Hylidae) from Brazil’s Atlantic Forest. PloS ONE 10: 1–21. 10.1371/journal.pone.0142893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira RB, Lima C. (2012) Anuran hotspot at Brazilian Atlantic rainforest invaded by the non-native Lithobatescatesbeianus Shaw 1802 (Anura, Ranidae). North-Western Journal of Zoology 8: 386–389. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira RB, Beard KH, Crump ML. (2016) Breeding guild determines frog distributions in response to edge effects and habitat conversion in the Brazil’s Atlantic Forest. PloS ONE 11: e0156781. 10.1371/journal.pone.0156781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Forti LR, da Silva TRA, Toledo LF. (2017) The acoustic repertoire of the Atlantic Forest Rocket Frog and its consequences for taxonomy and conservation (Allobates, Aromobatidae). ZooKeys 692: 141–153. 10.3897/zookeys.692.12187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DR. (2018) Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History, New York. http://research.amnh.org/herpetology/amphibia/index.html [accessed on 15 August 2017]

- Gower DJ, Wilkinson M. (2005) The conservation biology of caecilians. Conservation Biology 19: 45–55. 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00589.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad CFB, Segalla MV, Bataus YSL, Caramaschi U. (2016) Avaliação do Risco de Extinção de Thoropapetropolitana (Wandolleck 1907). http://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/faunabrasileira/estado-de-conservacao/7521-anfibios-thoropa-petropolitana [Accessed on 17 April 2017]

- Heyer WR, Rand AS, Cruz CAG, Peixoto OL. (1988) Decimations, extinctions, and colonizations of frog populations in Southeast Brazil and their evolutionary implications. Biotropica 20: 230–235. 10.2307/2388238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IUCN (2008) Guidelines for using the IUCN red list categories and criteria. Version 11. Prepared by the Standards and Petitions Subcommittee. www.iucnredlist.org [accessed on 15 August 2017]

- Lourenço-de-Moraes R, Ferreira RB, Fouquet A, Bastos R. (2014) A new diminutive frog of the genus Adelophryne Hoogmoed and Lescure 1984 (Amphibia, Anura, Eleutherodactylidae) from the Atlantic forest of Espírito Santo, Brazil. Zootaxa 3846: 348–360. 10.11646/zootaxa.3846.3.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço-de-Moraes R, Campos FS, Ferreira RB, Beard K, Solé M, Bastos RP. (2019) Back to the future: the role of climatic refuges in amphibians hotspot Atlantic Forest. Biodiversity and Conservation 28(5): 1049–1073. 10.1007/s10531-019-01706-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JD. (2005) Discovery of the richest frog fauna in the world. An exploration of the forests to the North of Leticia. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 29: 581–588. [Google Scholar]

- Maciel AO, Santana DJ, da Silva ET, Feio RN. (2009) Amphibia, Gymnophiona, Caeciliidae, Siphonopshardyi Boulenger 1888: Distribution extension, new state record and notes on meristic data. Check List 5: 919–921. 10.15560/5.4.919 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel AO, Hoogmoed MS. (2011) Taxonomy and distribution of caecilian amphibians (Gymnophiona) Of Brazilian Amazonia, with a key to their identification. Zootaxa 2984: 1–53. 10.11646/zootaxa.2984.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marciano-Jr E, Lantyer-Silva ASF, Solé M. (2017) A new species of Phyllodytes Wagler 1830 (Anura, Hylidae) from the Atlantic Forest of southern Bahia, Brazil. Zootaxa 4238: 135–142. 10.11646/zootaxa.4238.1.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes SL, Padovan MP. (2000) A Estação Biológica de Santa Lúcia, Santa Teresa, Espírito Santo. Boletim Museu Biologia Mello Leitão 11/12: 7–34.

- Mônico AT, Ferreira RB, Lauvers WD, Mattos RO, Clemente Carvalho RBG. (2016) Itapotihylalangsdorffii (Perereca castanhola; Ocellated Treefrog). Head Abnormality. Herpetological Review 47: 278–279. [Google Scholar]

- Olson DM, Dinerstein E, Wikramanayake ED, Burgess ND, Powell GVN, Underwood EC, D’amico JA, Itoua I, Strand HE, Morrison JC, Loucks CJ, Allnutt TF, Ricketts TH, Kura Y, Lamoreux JF, Wettengel WW, Hedao P, Kassem KR. (2001) Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: a new map of life on Earth. BioScience 51: 933–938. 10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:TEOTWA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI]

- Oommen VO, Measey GJ, Gower DJ, Wilkinson M. (2000) Distribution and abundance of the caecilian Gegeneophisramaswamii (Amphibia, Gymnophiona) in southern Kerala. Current Science 79: 1386–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Passamani M, Mendes SL, Chiarello AG. (2000) Non-volant mammals of the Estação Biológica de Santa Lúcia and adjacents areas of Santa Teresa, Espírito Santo, Brazil. Boletim do Museu de Biologia Mello Leitão 11/12: 201–214.

- Pimenta BVS, Cruz CAG, Caramaschi U. (2014) Taxonomic review of the species complex of Crossodactylusdispar Lutz 1925 (Anura, Hylodidae). Arquivos de Zoologia 45: 1–33. 10.11606/issn.2176-7793.v45i1p1-33 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pombal Jr JP, Gasparini JL. (2006) A new Brachycephalus (Anura, Brachycephalidae) from the Atlantic Rainforest of Espírito Santo, southeastern Brazil. South American Journal Herpetology 1: 87–93. 10.2994/1808-9798(2006)1[87:ANBABF]2.0.CO;2 [DOI]

- Ramos AD, Gasparini JL. (2004) Anfíbios do Goiapaba-Açu. Gráfica Santo Antônio, Fundão, Brazil, 75 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro MC, Metzger JP, Martensen AC, Ponzoni FJ, Hirota MM. (2009) The Brazilian Atlantic forest: how much is left, and how is the remaining forest distributed? Implications for conservation. Biological Conservation 142: 1141–1153. 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.02.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzini CT. (1979) Tratado de Fitogeografia do Brasil: aspectos sociológicos e florísticos. Editora Hucitec Ltda & Ed. Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 374 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Rödder D, Teixeira RL, Ferreira RB, Dantas RB, Pertel W, Guarniere GJ. (2007) Anuran hotspots: the municipality of Santa Teresa, Espírito Santo, southeastern Brazil. Salamandra 43: 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez LO, Duellman WE. (1994) Guide to the frogs of the Iquitos region, Amazonian Peru. University of Kansas Natural History Museum Special Publication 22: 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rossa-Feres D, Garey MV, Caramaschi U, Napoli MF, Nomura FA, Bispo A, Brasileiro CA, Thomé MT, Sawaya RJ, Conte CE, Cruz CAG, Nascimento LB, Gasparini JL, Almeida AP, Haddad CFB. (2017) Anfíbios da Mata Atlântica: Lista de espécies, histórico dos estudos, biologia e conservação. In: Monteiro Filho EML, Conte CE (Eds) Revisões em Zoologia: Mata Atlântica, Curitiba: Editora UFPR, 237–314.

- Scaramuzza CAM, Simões LL, Rodrigues ST, Accacio GM, Hercowitz M, Rosa MR, Goulart W, Pinagé ER, Soares MS. (2011) Visão da Biodiversidade da Ecorregião Serra do Mar: domínio biogeográfico Mata Atlântica. Brasília, WWF-Brasil, 167 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Schloegel LM, Ferreira CM, James TY, Hipolito M, Longcore JE, Hyatt AD, Yabsley M, Martins AMCRPF, Mazzoni R, Davies AJ, Daszak P. (2010) The North American bullfrog as a reservoir for the spread of Batrachochytriumdendrobatidis in Brazil. Animal Conservation 13: 53–61. 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2009.00307.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Segalla MV, Caramaschi U, Cruz CAG, Grant T, Haddad CFB, Garcia PCA, Berneck BVM, Langone JA. (2016) Brazilian Amphibians: list of species. Herpetologia Brasileira 5: 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Silva ET, Ribeiro-Filho OP, Feio RN. (2011) Predation of native anurans by invasive bullfrogs in southeastern Brazil: spatial variation and effect of microhabitat use by prey. South American Journal of Herpetology 6: 1–10. 10.2994/057.006.0101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva ET, Peixoto MAA, Leite FSF, Feio RN, Garcia PCA. (2018) Anuran distribution in a highly diverse region of the Atlantic Forest: the Mantiqueira mountain range in southeastern Brazil. Herpetologica 74: 294–305. 10.1655/Herpetologica-D-17-00025.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simon JE. (2000) Composição da avifauna da Estação Biológica de Santa Lúcia, Santa Teresa - ES. Boletim do Museu de Biologia Mello Leitão 11/12: 149–170.

- Simon JE, Peres J. (2012) Revisão da distribuição geográfica de Phyllodyteskautskyi Peixoto, Cruz 1988 (Amphibia, Anura, Hylidae). Boletim do Museu de Biologia Mello Leitão 29: 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- SOS Mata Atlântica. (2013) Atlas dos Remanescentes Florestais da Mata Atlântica. Período 2013–2014. http://www.sosma.org.br/ [accessed on 11 February 2017]

- Silvano DL, Pimenta BVS. (2003) Diversidade de anfíbios na Mata Atlântica do Sul da Bahia. In: Prado PI, Landau EC, Moura RT, Pinto LPS, Fonseca GAB, Alger K (Eds) Corredor de Biodiversidade na Mata Atlântica do Sul da Bahia. IESB, CI, CABS, UFMG, UNICAMP, Ilhéus, CD-ROM.

- Stuart S, Chanson J, Cox N, Young B, Rodrigues A, Fischman D, Waller R. (2004) Status and trends of amphibian declines and extinctions worldwide. Science 306: 1783–1786. 10.1126/science.1103538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabarelli M, Aguiar AV, Ribeiro MC, Metzger JP, Peres CA. (2010) Prospects for biodiversity conservation in the Atlantic forest: lessons for aging human-modified landscapes. Biological Conservation 143: 2328–2340. 10.1016/j.biocon.2010.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomaz LD, Monteiro R. (1997) Composição florística da Mata Atlântica de encosta da Estação Biológica de Santa Lúcia, município de Santa Teresa, Espírito Santo. Boletim Museu Biologia Mello Leitão 7: 3–48. [Google Scholar]

- Verdade VK, Rodrigues MT. (2007) Taxonomic review of Allobates (Anura, Aromobatidae) from the Atlantic Forest, Brazil. Journal of Herpetology 41: 566–580. 10.1670/06-094.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verdade VK, Rodrigues MT, Pavan D. (2009) Anfíbios anuros da Reserva Biológica de Paranapiacaba e entorno, pp. 579–604. In: Lopes IMS, Kirizawa M, Melo MRF (Eds) Patrimônio da Reserva Biológica do Alto da Serra de Paranapiacaba. A antiga Estação Biológica do Alto da Serra, Instituto de Botânica, São Paulo, 720 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Verdade VK, Valdujo PH, Carnaval ACOQL, Schiesari C, Toledo LF, Mott T, Andrade G, Eterovick PC, Menin M, Pimenta BVS, Lisboa CS, Paula DC, Silvano D. (2012) A leap further: the Brazilian Amphibian Conservation Action Plan. Alytes International Journal of Batrachology 29: 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Walker M, Gasparini JL, Haddad CFB. (2016) A new polymorphic species of egg-brooding frog of the genus Fritziana from southeastern Brazil (Anura, Hemiphractidae). Salamandra 52: 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Weygoldt P. (1986) Beobachtungen Zur Ökologie und biologie von fröschen an einem neotropischen bergbach. Zoologische Jahrbücher (Systematik) 113: 429–454. [Google Scholar]

- Weygoldt P. (1989) Changes in the composition of mountain stream frog communities in the Atlantic mountains of Brazil: frogs as indicators of environmental deterioration? Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment 243: 249–255. 10.1080/01650528909360795 [DOI]

- Wilkinson M, Nussbaum RA. (1999) Evolutionary relationships of the lungless caecilian Atretochoanaeiselti (Amphibia, Gymnophiona, Typhlonectidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 126: 191–223. 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1999.tb00153.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young BE, Stuart SN, Chanson JS, Cox NA, Boucher TM. (2004) Disappearing jewels: The status of new world amphibians. Nature Serve, Arlington, VA, 53 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Zocca CZ, Tonini JFR, Ferreira RB. (2014) Uso do espaço por anuros em ambiente urbano de Santa Teresa, Espírito Santo. Boletim do Museu de Biologia Mello Leitão 35: 105–117. [Google Scholar]