Abstract

Legionella pneumophila is an organism of public health interest for its presence in water supply systems and other humid thermal habitats. In this study, ten cell-free supernatants produced by Lactobacillus strains were evaluated for their ability to inhibit L. pneumophila strains isolated from hot tap water. Production of antimicrobial substances by Lactobacillus strains were assessed by agar well diffusion test on BCYE agar plates pre-inoculated with L. pneumophila. Cell-free supernatants (CFS) showed antimicrobial activity against all Legionella strains tested: L. rhamnosus and L. salivarius showed the highest activity. By means of a proton-based nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectroscopy, we detected and quantified the Lactobacillus metabolites of these CFSs, so to gain information about which metabolic pathway was likely to be connected to the observed inhibition activity. A panel of metabolites with variations in concentration were revealed, but considerable differences among inter-species were not showed as reported in a similar work by Foschi et al. (2018). More than fifty molecules belonging mainly to the groups of amino acids, organic acids, monosaccharides, ketones, and alcohols were identified in the metabolome. Significant differences were recorded comparing the metabolites found in the supernatants of strains grown in MRS with glycerol and the same strains grown in MRS without supplements. Indeed, pathway analysis revealed that glycine, serine and threonine, pyruvate, and sulfur metabolic pathways had a higher impact when strains were grown in MRS medium with a supplement such as glycerol. Among the metabolites identified, many were amino acids, suggesting the possible presence of bacteriocins which could be linked to the anti-Legionella activity shown by cell-free supernatants.

Keywords: Legionella pneumophila, Lactobacillus spp., antibacterial activity, metabolomics, metabolome analysis, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, metabolic pathway analysis

Introduction

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are commensal bacteria widely studied for their postbiotic products, a term which indicates the majority of the metabolites referring to soluble factors secreted by bacteria during their cycle-life and/or released after membrane lysis (Aguilar-Toala et al., 2018). Among these by-products, there are both biosurfactants and bacteriocins (Dykes, 1995; Van Hamme et al., 2006). The former are surface-active compounds including glycolipids, lipopeptides, lipoproteins, phospholipids, and fatty acids that reduce surface and interfacial tension in both aqueous solutions and hydrocarbon mixtures (Desai and Banat, 1997). As for bacteriocins, they are cationic and amphipathic small molecules with antagonistic activity usually against microorganisms closely related to the producing strain (Banerjee et al., 2013). For this reason, the bacteriocin-producing microorganisms have developed a specific immunity, mediated by a gene encoding for an immunity protein that protects the producers from their own bacteriocin (Kristiansen et al., 2016). The mechanism of action of bacteriocins produced by Gram positive bacteria is mostly related to the proton motive force (PMF) dissipation and can be further divided into subclasses on the basis of the energy required (Bruno and Montville, 1993).

Lactobacillus spp. are well known for their production of antimicrobial compounds, including biosurfactants, bacteriocins and bacteriocin-like peptides (BLIS) (Ruiz et al., 2012; Madhu and Prapulla, 2014; Sharma and Saharan, 2016; Fuochi et al., 2017, 2018).

Nowadays, many of these molecules are partially or entirely characterized (Gautam and Sharma, 2009; Hata et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2013; Ge et al., 2016), but it has been assumed that every Lactobacillus strain is able to produce its own peculiar postbiotics.

In this contest, component medium, in vitro, or diet, in vivo, have significant impacts on the probiotic function; this is especially notable for individual food components that are present in high quantities and have known relevance to microbial growth and metabolism (Yin et al., 2018). For example, cell growth can be maintained or enhanced upon the addition of glycerol to anaerobic glucose cultures of Lactobacillus sp. changing their metabolism (Westbrook et al., 2018).

Moreover, in recent years, postbiotics have attracted significant attention for their potential use for clinical applications (Tsilingiri and Rescigno, 2013), as safe additives for food preservation (Ahmad Rather et al., 2013), and for other applications such as disinfection/emulsification for industrial uses (Meylheuc et al., 2006; Luna et al., 2013). Gram-positive bacteria produce, above all, small cationic peptides weighting less than 6 kDa and narrow range spectrum. Nevertheless, there are exceptions; for instance, some Lactobacillus strains have shown activity against pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae (Fuochi, 2016; Fuochi et al., 2017). In the same way, a strain of Staphylococcus warneri has shown the production of a little hemolytic peptide (22 amino acids) which inhibited the growth of Legionella spp. (Hechard et al., 2005).

Legionellae are ubiquitous, and they could live as free-living planktonic forms, as sessile cells within a biofilm (Berlanga and Guerrero, 2016) or as intracellular parasites of protozoans (Hsu et al., 2011). L. pneumophila, in particular, is an organism of public health interest for its presence in water supply systems and other humid thermal habitats (e.g., air conditioners, cooling towers, hospital equipment, water fountains, etc.). It is the causative agent of Pontiac fever – a mild febrile illness – and Legionnaire’s disease or legionellosis – an acute and sometimes life-threatening pneumonia, which can occur as a nosocomial or travel-associated infection, sporadically or as part of an outbreak (Diederen, 2008).

At present, US-EPA listed disinfectants for drinking water are all based on the chlorine atom1. The efficacy against Legionella varies significantly across disinfectants because the bacterium can resist disinfection, especially when inside amoeba or in biofilms (Abdel-Nour et al., 2013).

In the present study, we evaluated ten CFSs produced by Lactobacillus strains belonging to different species, capable of producing molecules which had a broad spectrum of inhibition (Fuochi, 2016; Fuochi et al., 2018), for their ability to inhibit Legionella pneumophila strains isolated from hot tap water. Furthermore, a preliminary characterization was performed by 1H-NMR analysis to identify a panel of molecules whose variations could be associated with the taxonomy (Foschi et al., 2017). It will be useful in correlating lactobacilli with their anti-microbial activity, with the aim of discovering a decontaminant product that would be appropriate for disinfecting water systems.

Materials and Methods

Water Sampling and Isolation of Legionella Strains

Thirty samples of tap-water were collected throughout a water distribution system without flushing and without flaming, according to the procedures reported in the Italian guidelines for Legionellosis Prevention (Ministero della Salute, 2016). Isolation of Legionella was performed in accordance with the standards procedures ISO 11731:1998, as described elsewhere (Coniglio et al., 2018). In brief, 1L of water from each sampling point was filtered using 0.2 μm polycarbonate filter (Sartorius Stedim Biotech GmbH, Goettingen, Germany) and each filter was vortexed for 15 min in 10 mL of the correspondent water sample to detach bacteria. For each concentrated water sample, an aliquot of 5 mL underwent immediate cultural examination while the remaining 5 mL was treated with heat by exposure to 50°C for 30 min. From both concentrated and heat-treated samples, aliquots of 0.1 mL were transferred onto one plate of BCYE agar (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom) and 0.1 mL onto one plate of Glycine Vancomycin Polymyxin Cycloheximide (GVPC) agar (Oxoid). Plates were incubated at 37°C in modified atmosphere (2.5% CO2). After 4, 8, and 14 days of incubation, colonies suggestive for Legionella grown on BCYE and GVPC were confirmed on the basis of cultural testing (lack of growth on CYE agar, Oxoid) and were subjected to identification using a latex agglutination test with polyvalent antisera (Legionella Latex Test, Oxoid) and monovalent antisera (Biogenetics Srl, Tokyo, Japan). The test allows the separate identification of L. pneumophila Serogroup 1 and Serogroups 7-14 and commonly isolated Legionella species.

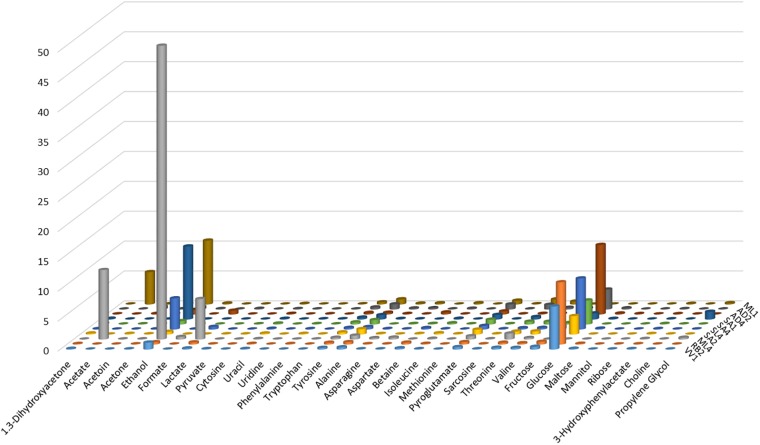

Molecular analysis was performed by real-time PCR (Ministero della Salute, 2016). Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted using Legionella DNA Extraction Kit (4LAB Diagnostics s.r.l., CR, Italy) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Afterward, DNA amplification and product detection were performed using MIC PCR cycler 1.4 (Bio Molecular System). All reactions were performed using Legionella pneumophila PCR Real-Time Kit (4LAB Diagnostics s.r.l., CR, Italy) in a final volume of 20 μL containing 5 μL of GAPDH mix, 0.5 μL of dNTP, 1.5 μL of MgCl, 2.5 μL of buffer, 10.25 μL of water, and 0.25 μL of Taq. The qPCR reaction contained following steps: 2 min at 95°C followed by 30 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C and 45 sec at 95°C. Finally, during amplification, the reporter dye (FAM) was measured. Data were analyzed with micPCR© software 1.4.1. (Bio Molecular System).

The strains of Legionella pneumophila were analyzed for their susceptibility to supernatants of Lactobacillus strains (Fuochi, 2016; Fuochi et al., 2017; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI], 2018).

Production of Antimicrobial Substances by Lactobacillus Strains

The antimicrobial substances produced by Lactobacillus strains were obtained as previously described: strains of Lactobacillus spp., previously isolated as already reported (Fuochi, 2016; Fuochi et al., 2017, 2018), were grown at 33°C in MRS broth (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) without supplements or with 20% glycerol for 72 h. Then, cells were separated by centrifugation (8,000 rpm, 25 min, 4°C) and CFSs were collected after filtration at 0.22 μm. Moreover, CFSs were adjusted at pH 6.8 with NaOH 1M (Toba et al., 1991).

Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity

For the evaluation of antimicrobial activity, agar well-diffusion test bioassay was performed with CFSs obtained from the growth in MRS with and without supplement (Fuochi, 2016; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI], 2018). 100 μL of each CFS were inoculated into wells made on pre-inoculated BCYE agar plates (Buffered Charcoal Yeast Extract Agar, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and inhibitory activity was measured against Legionella pneumophila strains (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI], 2018). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 72 h in a humid environment (2.5% CO2) and the inhibition zones were then measured in mm by a caliper.

An internal control was performed using E-tests on BCYE-α (Liofilchem S.R.L., Teramo, Italy) with erythromycin (ERY) and ciprofloxacin (CIP), ranging from 0.016 to 256 μg/mL and 0.002 to 32 μg/mL, respectively. MIC values of ERY and CIP were taken as the lowest concentration of antibiotic at which the zone of inhibition intersected the E-test strip (De Giglio et al., 2015). The experiments were performed six times.

1H-NMR Analysis

Seven hundred μL of each CFS were added to 100 μL of a D2O solution of 3-(trimethylsilyl)-propionic-2,2,3,3-d4 acid sodium salt (TSP, 10 mmol) as internal standard.

This solution was adjusted to pH 7.00 by 1M phosphate buffer solution (PBS). Furthermore, NaN3 (2 mM) was added to prevent the proliferation of microorganisms during the analysis.

1H-NMR spectra were recorded at 298 K with an AVANCE III spectrometer (Bruker, Milan, Italy) operating at a frequency of 600.13 MHz. Following previous works on a variety of biofluids (Ventrella et al., 2016; Le Guennec et al., 2017; Foschi et al., 2018; Parolin et al., 2018), the signals from broad resonances originating from large macromolecules were suppressed by a CPMG-filter composed of 400 echoes separated by 0.400 ms and created with a 180° pulse of 0.024 ms, for a total filter of 330 ms. The residual water signal was suppressed by presaturation.

As pictorially described in Supplementary Figure S1, the signals were assigned by comparing their chemical shift and multiplicity with Chenomx software data bank (Chenomx Inc., Canada, ver 8.2), with standards (Chenomx Inc., Canada, ver. 10) and HMDB (Human Metabolome Data Base ver. 2) data bank. Spectra were processed for quantification as detailed elsewhere (Foschi et al., 2018). Integration of the signals was performed for each molecule by means of rectangular integration.

Related Pathway Analysis

Pathway analysis was performed on MetaboAnalyst platform, ver 4.0 (Chong et al., 2018). The most relevant pathways involved were identified by combining the results obtained from the pathway enrichment analysis, as suggested by Wu et al. (2017). Graphs were generated using MetaboAnalyst platform ver 4.0.

Statistical Analysis

The experiments for antimicrobial activity bioassay were performed six times. Where applicable, data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with correction for multiple comparisons by Bonferroni.

Results

Isolation and Identification of Legionella Strains

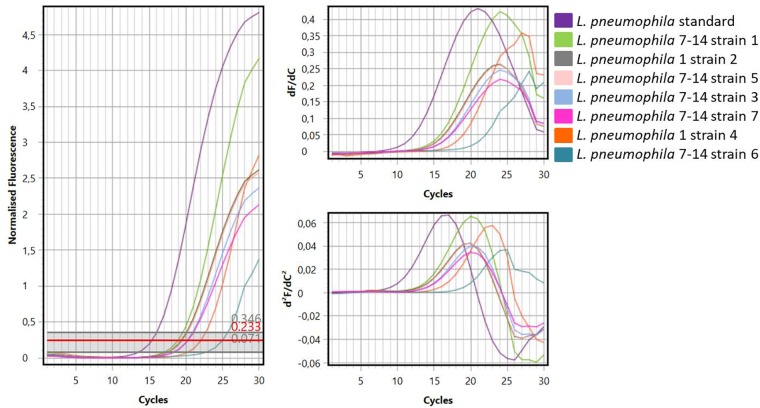

Figure 1 showed one plate of BCYE agar (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom) after 14 days of incubation (on the left) and the subsequent identification of presumptive Legionella spp. using latex agglutination test (on the right) with mono and polyvalent antisera (Legionella Latex Test, Oxoid). Agglutination of the blue polystyrene ‘latex’ particles within 1 min was considered a positive reaction. On the 30 hot water samples collected, 7 strains of L. pneumophila were detected: namely 5 strains belong to Sg 7–14 and 2 strains belong to Sg 1. Moreover, amplification curves obtained by RT-PCR as a second confirmation of identification were showed in Figure 2.

FIGURE 1.

Left, Buffered Charcoal Yeast Extract (BCYE) agar after 14 days of incubation at 37°C in modified atmosphere (2.5% CO2). Legionella colonies appeared white-gray, shiny, round in shape with whole edges; Right, identification of Legionella pneumophila using latex agglutination test with mono (Lp Sg1) and polyvalent antisera (Lp Sg 7–14).

FIGURE 2.

Curves generated by amplification of standard Legionella DNA and DNA samples extracted from Legionella strains.

Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity

CFSs of lactobacilli grown in MRS without supplement did not show activity (data not shown). Instead, CFSs obtained from growth with glycerol showed antimicrobial activity against all Legionella strains tested. This activity was assessed by inhibition zones on the plates, indicating the lack of growth of Legionella in the presence of these supernatants (Table 1). The major inhibition effects were assessed for AD2 L. rhamnosus (30 mm) and ML1 L. salivarius (30 mm) against 1 Lp 7–14 strain, as well as for AD2 L. rhamnosus against 3 Lp 7–14.

Table 1.

Zones of inhibition measured in mm (diameter) caused by cell-free supernatants of Lactobacillus spp. (grown in MRS with the supplement glycerol) against Legionella spp.

| Inhibition zones (mm) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | 1 Lp 7–14 | 2 Lp Sg 1 | 3 Lp 7–14 | 4 Lp Sg 1 | 5 Lp 7–14 | 6 Lp 7–14 | 7 Lp 7–14 |

| VV1 L. crispatus | 21.9 ± 0.1 | 17.2 ± 0.2 | 24.2 ± 0.1 | 22.9 ± 0.1 | 20.2 ± 0.1 | 19.1 ± 0.1 | 23.0 ± 0.1 |

| RB2 L. crispatus | 20.9 ± 0.1 | 17.9 ± 0.1 | 21.8 ± 0.3 | 20.8 ± 0.1 | 19.8 ± 0.1 | 22.1 ± 0.3 | 25.1 ± 0.1 |

| ML4 L. fermentum | 24.2 ± 0.2 | 15.1 ± 0.1 | 22.9 ± 0.1 | 21.4 ± 0.2 | 18.2 ± 0.1 | 20.8 ± 0.2 | 23.2 ± 0.3 |

| SA2 L. gasseri | 23.8 ± 0.2 | 14.8 ± 0.2 | 22.7 ± 0.3 | 21.2 ± 0.2 | 17.8 ± 0.2 | 21.1 ± 0.1 | 23.2 ± 0.2 |

| SL4 L. gasseri | 24.9 ± 0.1 | 17.2 ± 0.1 | 25.2 ± 0.1 | 22.7 ± 0.3 | 19.2 ± 0.1 | 19.3 ± 0.1 | 21.8 ± 0.3 |

| SA4 L. gasseri | 23.9 ± 0.1 | 15.4 ± 0.2 | 23.2 ± 0.1 | 20.6 ± 0.1 | 18.1 ± 0.3 | 20.3 ± 0.3 | 22.9 ± 0.2 |

| SA1 L. jensenii | 16.2 ± 0.2 | 18.2 ± 0.1 | 23.7 ± 0.3 | 15.4 ± 0.2 | 12.3 ± 0.1 | 18.6 ± 0.1 | 24.1 ± 0.1 |

| AD4 L. rhamnosus | 18.9 ± 0.1 | 19.8 ± 0.1 | 21.2 ± 0.1 | 18.7 ± 0.2 | 18.8 ± 0.1 | 21.7 ± 0.1 | 21.2 ± 0.3 |

| AD2 L. rhamnosus | 30.2 ± 0.2 | 11.7 ± 0.3 | 30.1 ± 0.1 | 17.3 ± 0.3 | 11.8 ± 0.3 | 22.2 ± 0.2 | 24.2 ± 0.2 |

| ML1 L. salivarius | 29.9 ± 0.1 | 13.2 ± 0.1 | 23.6 ± 0.3 | 16.4 ± 0.1 | 11.1 ± 0.2 | 12.1 ± 0.1 | 24 ± 0.1 |

The experiments were performed six times. Results have been expressed as mean ± SD.

The activity of ERY and CIP tested against L. pneumophila isolates and one reference strain (L. pneumophila NCTC 12821) was reported in Table 2. We decided to use E-test on BCYE-α as internal control because it is a rapid and accurate method for routine susceptibility testing of Legionella spp., as previously described (Bruin et al., 2012; De Giglio et al., 2015).

Table 2.

MIC values of ERY and CIP expressed as μg/mL for L. pneumophila isolates for positive internal control.

| Drug | 1 Lp 7–14 | 2 Lp Sg 1 | 3 Lp 7–14 | 4 Lp Sg 1 | 5 Lp 7–14 | 6 Lp 7–14 | 7 Lp 7–14 | Lp sg NCTC 12821 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERY | 0.125 | 0.094 | 0.125 | 0.094 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.06 |

| CIP | 0.250 | 0.250 | 0.125 | 0.250 | 0.250 | 0.250 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

MIC values of ERY were lower than CIP, but there was no significant difference among the MIC values of environmental isolates and NCTC strain.

1H-NMR Analysis

Thirty-two molecules were identified and quantified in the metabolome of the CFSs produced by ten strains of Lactobacillus grown in MRS with glycerol (Supplementary Figure S1). These metabolites belong mainly to families of organic acids, ketones, alcohols, amino acids, and monosaccharides (Table 3). The quantities of the MRS components were reported in Table 4. As done in previous works, the analysis of the metabolic study was carried out on a single sample of CFS, only once (Foschi et al., 2017, 2018; Parolin et al., 2018). Nevertheless, to estimate the measurements reproducibility, the quantification procedure was repeated three times and from a preliminary investigation the median coefficient of variation for the quantified molecules was found to be 3.37.

Table 3.

Quantification of metabolites detected by 1H-NMR of the ten cell-free supernatants produced by Lactobacillus spp. grown in MRS with glycerol (20% v/v) expressed as mmoL.a

| VV1 | RB2 | ML4 | SA2 | SL4 | SA4 | SA1 | AD4 | AD2 | ML1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolites | ||||||||||

| Organic acids (alcohols, aldehydes, and ketones) | ||||||||||

| 1.3-Dihydroxyacetone | 0.1160 | 0.0914 | –b | 0.1733 | 0.0667 | 0.1601 | 0.1243 | 0.0333 | – | – |

| Acetate | – | – | 11.6086 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5.4060 |

| Acetoin | – | – | 0.0153 | 0.1002 | – | 0.0311 | – | 0.0935 | 0.4773 | 0.0572 |

| Acetone | 0.0404 | 0.0374 | 0.0225 | 0.0371 | 0.0337 | 0.0288 | – | 0.0468 | 0.0263 | 0.0049 |

| Ethanol | 1.1489 | 0.3767 | 49.1248 | 0.4433 | 5.1998 | 0.5562 | 12.2024 | 0.7748 | 0.4050 | 10.6746 |

| Formate | – | 0.0051 | 0.4260 | – | – | 0.0249 | – | 0.0037 | 0.0661 | 0.1656 |

| Lactate | 0.1762 | 0.3521 | 6.7589 | – | 0.4303 | – | – | 0.6278 | – | – |

| Pyruvate | 0.0609 | 0.0298 | – | 0.0350 | – | – | – | 0.0014 | 0.1049 | 0.0133 |

| Nucleosides and nucleotides | ||||||||||

| Cytosine | 0.0098 | 0.0080 | – | 0.0258 | 0.0103 | 0.0365 | 0.0043 | – | – | – |

| Uracil | 0.0913 | 0.1011 | 0.0697 | 0.1575 | 0.1214 | 0.1535 | 0.1128 | 0.1027 | 0.0624 | 0.0962 |

| Uridine | 0.0051 | 0.0049 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.0058 | 0.0157 | – |

| Amino acids and derivatives | ||||||||||

| Phenylalanine | – | 0.0785 | – | 0.1060 | 0.0663 | 0.0629 | 0.0432 | 0.0437 | – | – |

| Tryptophan | – | – | 0.0163 | 0.0209 | – | 0.0252 | 0.0391 | 0.0100 | 0.0136 | 0.0373 |

| Tyrosine | 0.2713 | 0.2863 | 0.2905 | 0.3510 | 0.2664 | 0.3558 | 0.3111 | 0.2579 | 0.3416 | 0.3533 |

| Alanine | 0.3561 | 0.3899 | 0.6423 | 0.8967 | 0.4111 | 0.7354 | 0.7214 | 0.2853 | 0.8579 | 0.8608 |

| Asparagine | 0.0414 | 0.0577 | 0.2247 | 0.0852 | 0.0754 | 0.0030 | 0.0880 | 0.0852 | 0.1728 | 0.1414 |

| Aspartate | 0.0332 | 0.0417 | 0.3168 | 0.0214 | 0.0314 | 0.0836 | 0.0357 | 0.0234 | 0.2074 | 0.2043 |

| Betaine | 0.2029 | 0.3092 | – | 0.0917 | 0.2443 | 0.0931 | – | 0.3463 | 0.0172 | – |

| Isoleucine | 0.0613 | 0.1082 | 0.1213 | 0.2106 | 0.0439 | 0.2016 | 0.1212 | 0.0224 | 0.1306 | 0.2062 |

| Methionine | 0.0075 | 0.0136 | – | 0.0584 | – | 0.0411 | 0.0051 | – | – | – |

| Pyroglutamate | 0.3944 | 0.3923 | 0.5473 | 0.8159 | 0.5996 | 0.7930 | 0.7598 | 0.5096 | 0.8496 | 0.6239 |

| Sarcosine | 0.0453 | 0.0421 | 0.0446 | 0.0578 | 0.0489 | 0.0538 | 0.0171 | 0.0357 | 0.0280 | 0.0392 |

| Threonine | 0.2956 | 0.2910 | 0.9926 | 0.4964 | 0.2264 | 0.4695 | 0.4104 | 0.1056 | 0.7721 | 0.8477 |

| Valine | 0.2742 | 0.2156 | 0.2496 | 0.5151 | 0.2613 | 0.4545 | 0.3531 | 0.1043 | 0.2749 | 0.4875 |

| Sugars and derivates | ||||||||||

| Fructose | 0.4516 | 0.4468 | – | 0.0847 | 0.5549 | 0.2224 | – | 0.5762 | 0.2541 | – |

| Glucose | 7.1884 | 10.3974 | – | 3.0722 | 8.5333 | 4.0134 | 1.0097 | 11.6231 | 3.3199 | – |

| Maltose | 0.1253 | 0.1195 | – | – | 0.1396 | – | 0.1020 | 0.1604 | 0.1925 | – |

| Mannitol | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.0761 | – | – |

| Ribose | 0.0171 | 0.0192 | – | 0.0075 | 0.0151 | 0.0107 | – | 0.0247 | 0.0105 | – |

| Others | ||||||||||

| 3-Hydroxyphenylacetate | 0.0690 | 0.0485 | 0.0900 | 0.0857 | 0.0757 | 0.0904 | 0.0326 | 0.0575 | 0.0567 | 0.1078 |

| Choline | 0.0072 | 0.0115 | 0.0112 | 0.0172 | 0.0117 | 0.0180 | – | 0.0117 | 0.0071 | – |

| 2,3-Butanediol | 0.0165 | 0.0042 | 0.2947 | 0.0070 | 0.0241 | 0.0065 | 1.2774 | 0.0060 | 0.0108 | 0.2168 |

aReferred to the quantities of substances found in the samples after subtracting the quantities of the components present in the MRS culture medium reported in Table 4; bThe value of quantification was negative after subtracting the quantities of the components of MRS culture medium.

Table 4.

Composition of 69966 MRS Broth (Lactobacillus Broth acc. to De Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe) Datasheet Sigma-Aldrich Co.a

| Ingredients | Grams/Liter |

|---|---|

| Peptone | 10.0 |

| Meat extract | 8.0 |

| Yeast extract | 4.0 |

| D-(+)-Glucose | 20.0 |

| Dipotassium hydrogen phosphate | 2.0 |

| Sodium acetate trihydrate | 5.0 |

| Triammonium citrate | 2.0 |

| Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate | 0.2 |

| Manganous sulfate tetrahydrate | 0.05 |

| 1H-NMR detection | mmoL |

| 1.3-Dihydroxyacetone | 0.0752 |

| Acetate | 36.7000 |

| Acetoin | 0.0248 |

| Acetone | 0.0116 |

| Ethanol | 0.0386 |

| Formate | 0.1120 |

| Lactate | 3.0400 |

| Pyruvate | 0.0581 |

| Cytosine | 0.0294 |

| Uracil | 0.1350 |

| Uridine | 0.0939 |

| Phenylalanine | 1.4000 |

| Tryptophan | 0.2440 |

| Tyrosine | 0.2281 |

| Alanine | 2.3300 |

| Asparagine | 0.1240 |

| Aspartate | 0.1930 |

| Betaine | 0.9820 |

| Isoleucine | 0.9150 |

| Methionine | 0.3370 |

| Pyroglutamate | 0.4340 |

| Sarcosine | 0.2500 |

| Threonine | 0.4360 |

| Valine | 1.5600 |

| Fructose | 0.2020 |

| Glucose | 8.4600 |

| Maltose | 0.1590 |

| Mannitol | 6.2500 |

| Ribose | 0.0346 |

| 3-Hydroxyphenylacetate | 0.1020 |

| Choline | 0.0786 |

| Propylene Glycol | 0.0121 |

aFinal pH 6.2 ± 0.2 at 25°C.

Among the most common molecules found in the literature are lactate, mannitol, glycine, betaine, acetate, ethanol, phenylalanine, formate, uridine, and isoleucine, as well as alanine and valine. Some of these molecules were already present in the culture medium; others are normal metabolites of lactobacilli (e.g., acetate and ethanol) while some are secondary metabolic products.

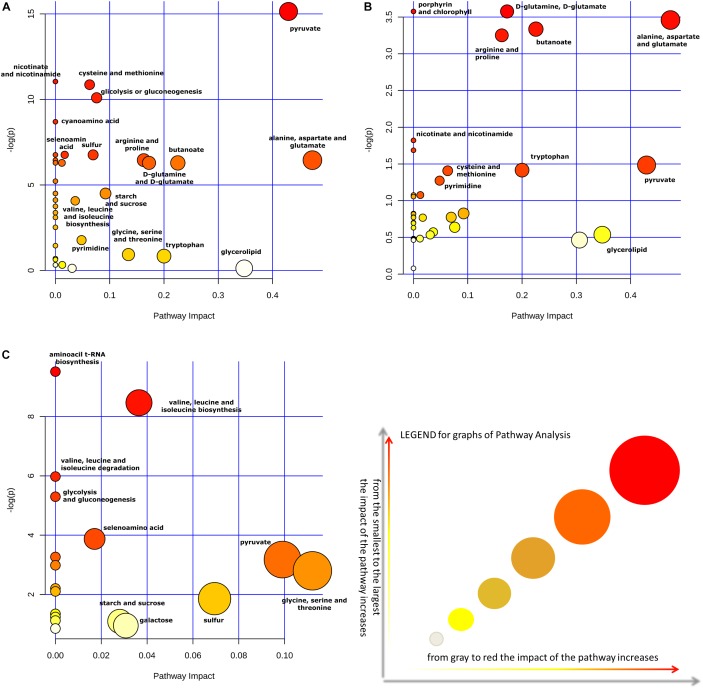

From the examination of the quantities of the identified metabolites, graphically reported in Figure 3, for each of the ten strains, clearly results that ML4 L. fermentum strain is particularly rich in ethanol (49.12 mmol), respect to all others strains. Moreover, in ML4 L. fermentum strain are present even elevate quantities of acetate (11.60 mmol) and lactate (6.75 mmol), that result absent in the other strains, with the exception of the ML1 L. salivarius (acetate = 5.40 mmol); finally, the glucose is completely absent so as in the ML1 L. salivarius strain. The quantities of all others metabolites not present particular and relevant differences.

FIGURE 3.

Graphical representation of the metabolite quantities (reported in Table 3) founded in the cell-free supernatants produced by the studied Lactobacillus strains grown in MRS with glycerol.

Related Pathway Analysis

The pathway analysis was performed on MetaboAnalyst platform, to identify the most relevant pathways triggered by the experimental conditions.

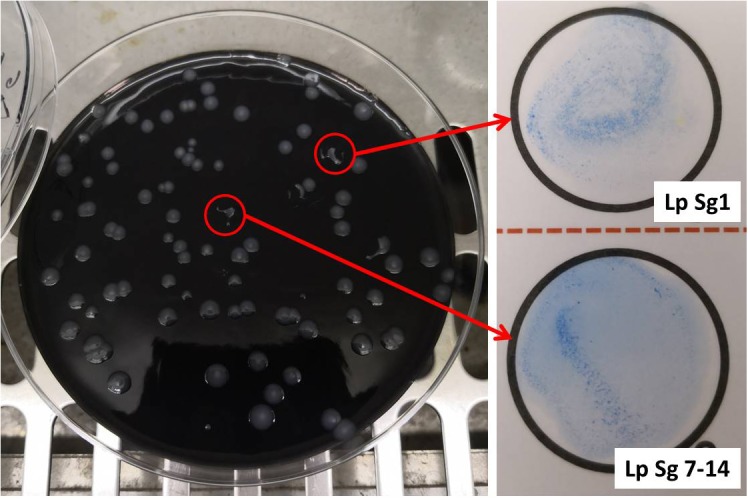

Moreover, the impact of glycerol on metabolic pathways of Lactobacillus strains was evaluated, by comparing pathway impact values when strains were grown with and without this supplement in the medium. The pathway impact of pyruvate metabolism, D-glutamine and D-glutamate metabolism, porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism, alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, butanoate metabolism, arginine and proline metabolism were found to be altered when Lactobacillus strains were grown in MRS with glycerol (Figure 4A,B). Furthermore, a comparative analysis between all metabolites identified and the most concentrated ones was performed only on CFSs produced with glycerol (Table 5).

FIGURE 4.

The metabolome view shows all matched pathways, according to the p-values, from the pathway enrichment analysis, and pathway impact values from the pathway topology analysis. Impact of pathways on Lactobacillus metabolism in presence (A) or absence (B) of the supplement glycerol in the medium. Panel (C) show the impact of pathways considering only the metabolites found in greater quantity in the CFSs. All analyses of metabolite cycles were carried out using Metaboanalyst software (http://www.metaboanalyst.ca). The most significant biochemical pathways were represented with circles in different colors and sizes. In particular, smaller circles or circles in lighter colors (white < gray) indicated that the metabolite is not in the data and it is also excluded from enrichment analysis; larger circles or circle in darker colors (yellow < orange < red) indicated higher-impact metabolic pathways.

Table 5.

Pathway analysis performed using MetaboAnalyst 4.0 about CFS of Lactobacillus strains grown in MRS with glycerol.a

| Pathway | Match Status | p | -log(p) | Holm p | FDR | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism | 2/32 | 0.0609 | 2.7981 | 1.0 | 0.5889 | 0.1121 |

| Pyruvate metabolism | 2/26 | 0.0416 | 3.1774 | 1.0 | 0.5182 | 0.0990 |

| Sulfur metabolism | 1/13 | 0.1557 | 1.8598 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0694 |

| Valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis | 4/26 | 0.0002 | 8.4648 | 0.0181 | 0.0091 | 0.0364 |

| Galactose metabolism | 1/37 | 0.3859 | 0.9521 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0307 |

| Starch and sucrose metabolism | 1/31 | 0.3345 | 1.0949 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0280 |

| Selenoamino acid metabolism | 2/18 | 0.0208 | 3.8727 | 1.0 | 0.3619 | 0.0170 |

| Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 1/42 | 0.4259 | 0.8535 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| D-Alanine metabolism | 1/3 | 0.0381 | 3.2670 | 1.0 | 0.5182 | 0.0 |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis | 6/66 | 7.38E-5 | 9.5129 | 0.0064 | 0.0064 | 0.0 |

| Phosphonate and phosphinate metabolism | 1/4 | 0.0505 | 2.9853 | 1.0 | 0.5494 | 0.0 |

| Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation | 3/23 | 0.0025 | 5.9758 | 0.2158 | 0.0736 | 0.0 |

| Streptomycin biosynthesis | 1/9 | 0.1103 | 2.204 | 1.0 | 0.9601 | 0.0 |

| Taurine and hypotaurine metabolism | 1/10 | 0.1219 | 2.1045 | 1.0 | 0.9641 | 0.0 |

| Glycolysis or Gluconeogenesis | 3/29 | 0.0050 | 5.2966 | 0.4207 | 0.1089 | 0.0 |

| Phenylalanine metabolism | 1/23 | 0.2599 | 1.3474 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| Phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis | 1/23 | 0.2599 | 1.3474 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis | 1/23 | 0.2599 | 1.3474 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| Pentose phosphate pathway | 1/26 | 0.2887 | 1.2421 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| Fructose and mannose metabolism | 1/30 | 0.3256 | 1.1220 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

aThe statistical p-values were calculated from enrichment analysis; the Holm p is the p-value adjusted by the Holm-Bonferroni method; the FDR p is the p-value adjusted using the false discovery rate; the impact is the pathway impact value calculated from pathway topology analysis.

Finally, Figure 4C allowed to evaluate in greater detail the metabolites found in higher quantities in the CFSs of the strains grown with glycerol thanks to a “zoom” of the biosynthetic pathways used by bacteria in this context. Indeed, as can be seen, the larger and darker circles showed that the biosynthetic pathways of valine, leucine, and isoleucine, as well as the pyruvate, glycine, serine, and threonine pathways had a more significant influence on the metabolism of these lactobacilli.

Discussion

Nowadays, the prevention of Legionella dissemination has an important role in the control of its proliferation in water systems and many chemical disinfection methods have been proposed (Bonetta et al., 2018; Coniglio et al., 2018).

Nevertheless, the research of LAB producers could lead to the discovery of molecules with strong antimicrobial activity for alternative less polluting decontamination method.

In this study, ten CFSs were produced by different species of Lactobacillus: L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. jensenii, L. fermentum, L. rhamnosus, and L. salivarius grown up with two different culture media. CFSs obtained from the growth in MRS without supplement did not show antibacterial activity; on the contrary, the ones obtained from the growth in MRS with glycerol showed anti-Legionella activity emphasizing the important role of nutrition on bacterial metabolism and the consequent production of postbiotics. Furthermore, CFSs produced by AD2 L. rhamnosus and ML1 L. salivarius followed by SL4 L. gasseri showed the strongest activity against two strains of Legionella pneumophila. It is interesting to note that the lactobacilli species found to be active against Legionella were already demonstrated to have considerable amensalistic characteristics such as resisting bile salts and acidic pH (Fuochi et al., 2015), as well as having the ability to produce biofilms, antibacterial, and antifungal activity (Fuochi et al., 2017, 2018).

In order to understand the subjects involved in the anti-Legionella activity 1H-NMR analysis was performed. Indeed, 1H-NMR spectroscopy proved to be a fast and reliable analytical technique to detect and quantify low molecular weight metabolites in different matrices and biological fluids (Laghi et al., 2014; Parolin et al., 2018), included intracellular and extracellular metabolic profiles of different Gram-positive (e.g., lactobacilli and Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) (Ammons et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2017).

A panel of metabolites with variations in concentration were revealed, but great differences among inter-species were not showed as reported in a similar work (Foschi et al., 2017).

Essential differences were recorded comparing the metabolites found in the supernatants of strains grown in MRS with glycerol and the same strains grown in MRS without this supplement.

Indeed, the presence or absence of glycerol in the medium has transformed the impact of pathways in the metabolism of Lactobacillus strains as expected. Acting by this way, in the two cases the role of pyruvate metabolism and alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism were changed. In particular, the impact of pyruvate is increased of 10 times; meanwhile, that one of alanine, aspartate and, glutamate is increased twice (Figure 4A,B).

Moreover, metabonomic research considering only the metabolites found in high quantity in the CFSs of Lactabacillus grown in MRS with glycerol revealed that glycine, serine, and threonine, pyruvate and sulfur metabolic pathways had a higher impact compared to the same strains grown in MRS without supplement (Figure 4C).

L. crispatus, L. gasseri, and L. salivarius strains are obligately homofermentative Lactobacillus spp. which means they degrade hexoses to pyruvate, which in turn is reduced by lactic fermentation to lactate by the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway (Willey et al., 2010). Instead, L. jensenii, L. rhamnosus, and L. fermentum strains are facultatively heterofermentative and obligately heterofermentative Lactobacillus spp., respectively. As it is well known, facultatively heterofermentative strains could use both Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway and Warburg-Dickens pathway, meanwhile obligately heterofermentative strains only the Warburg–Dickens pathway (Nelson et al., 2017). The result is the production of pyruvate and lactate as well as ethanol and acetate molecules, consistently with the high concentrations detected by 1H-NMR. Whereas the antibacterial activity of these molecules is renowned for a long time (Houtsma et al., 1993; Oh and Marshall, 1993; Lee et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2015; Stanojevic-Nikolic et al., 2016), our attention was focused on other molecules identified by metabolomics analysis such as uridine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and betaine.

For instance, Yamaguchi et al. (2015) have synthesized uridine derivatives containing isoxazolidine which have shown good activity against H. influenzae ATCC 10211 and moderate activity against E. faecalis SR7914 with resistance to vancomycin. Regards both tyrosine and phenylalanine, analogous cationic surfactants were synthesized, as ester derivatives, and analyzed; their antibacterial action was more pronounced on Gram-positive strains compared to Gram-negative ones (Joondan et al., 2014). Furthermore, benzyl derivatives of betaine showed bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains (Cosquer et al., 2004).

Based on these results, many amino acids as well as other metabolites with recognized antibacterial activity were present in our CFSs. Besides, these molecules were only the small “free ones” detected by 1H-NMR, due to the applied CPMG-filter.

The presence of many amino acids could suggests a possible participation of a peptide or a protein in the antibacterial activity, hypothesis already partially confirmed by a previous work (Fuochi et al., 2018). In fact, in that study, the antimicrobial activity of these CFSs were inactivated by enzymes such as trypsin and proteinase K suggesting the presence of proteinaceous molecules, and for this reason we referred to them as BLIS. Nevertheless, it is important to remember, as previously said, that other compounds can be potentially toxic to specific microbes (Singh et al., 2007). Indeed, several studies reported the potential of lactobacilli as microbial surfactants which play an important role as no-conventional antibacterial products against various pathogens (Velraeds et al., 1996; Tahmourespour et al., 2011; Cornea et al., 2016; Sharma and Saharan, 2016).

In the category of biosurfactants are included low molecular-weight compounds such as lipopeptides and glycolipids (Sharma and Saharan, 2016). Anti-Legionella activity has already been demonstrated by similar bacterial products, for instance a strain of Bacillus subtilis produces the surfactin, a lipopeptide that successfully eliminated 90% of a 6-day-old biofilm (Loiseau et al., 2015). Moreover, Héchard et al. (Hechard et al., 2005), described a new bacteriocin secreted by S. warneri RK with anti-Legionella activity. Then, sugars, amino acids, and organic acids reported in Table 3 could be part of this kind of molecules.

Although, the full characterization of the molecules present in CFSs has not yet occurred, this is one of the few papers describing an active microbial postbiotic against L. pneumophila. Certainly, our results represent the starting point for more in-depth studies, and analysis by MALDI MS are in progress in order to thoroughly investigate and characterize the postbiotic molecule involved in the antimicrobial activity of Lactobacillus CFSs with the aim of studying the appropriate method for the production on large-scale of this new eco-disinfectant for the water systems.

Author Contributions

VF and PF conceived the study. VF, LL, MAC, AR, and PF provided the methodology. VF, LL, and AR developed the software. VF, MAC, LL, and MC curated the data. VF, MC, and AS wrote the original draft of the manuscript. VF, MC, AS, and PF reviewed, wrote, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- BCYE

Buffered Charcoal Yeast Extract

- BLIS

bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances

- CFS

cell-free supernatant

- MIC

minimal inhibitory concentration

- MRS

De Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01403/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abdel-Nour M., Duncan C., Low D. E., Guyard C. (2013). Biofilms: the stronghold of Legionella pneumophila. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 21660–21675. 10.3390/ijms141121660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Toala J. E., Garcia-Varela R., Garcia H. S., Mata-Haro V., Gonzalez-Cordova A. F., Vallejo-Cordoba B., et al. (2018). Postbiotics: an evolving term within the functional foods field. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 75 105–114. 10.1016/j.tifs.2018.03.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad Rather I., Seo B. J., Rejish Kumar V. J., Choi U. H., Choi K. H., Lim J. H., et al. (2013). Isolation and characterization of a proteinaceous antifungal compound from Lactobacillus plantarum YML007 and its application as a food preservative. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 57 69–76. 10.1111/lam.12077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammons M. C. B., Tripet B. P., Carlson R. P., Kirker K. R., Gross M. A., Stanisich J. J., et al. (2014). Quantitative NMR metabolite profiling of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible staphylococcus aureus discriminates between biofilm and planktonic phenotypes. J. Proteome Res. 13 2973–2985. 10.1021/pr500120c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S. P., Dora K. C., Chowdhury S. (2013). Detection, partial purification and characterization of bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus brevis FPTLB3 isolated from freshwater fish: bacteriocin from Lb. brevis FPTLB3. J. Food Sci. Technol. 50 17–25. 10.1007/s13197-011-0240-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlanga M., Guerrero R. (2016). Living together in biofilms: the microbial cell factory and its biotechnological implications. Microb. Cell Fact. 15:165. 10.1186/s12934-016-0569-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonetta S., Pignata C., Bonetta S., Meucci L., Giacosa D., Marino E., et al. (2018). Effectiveness of a neutral electrolysed oxidising water (NEOW) device in reducing Legionella pneumophila in a water distribution system: a comparison between culture, qPCR and PMA-qPCR detection methods. Chemosphere 210 550–556. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.07.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruin J. P., Ijzerman E. P., den Boer J. W., Mouton J. W., Diederen B. M. (2012). Wild-type MIC distribution and epidemiological cut-off values in clinical Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 isolates. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 72 103–108. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno M. E., Montville T. J. (1993). Common mechanistic action of bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59 3003–3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T. T., Sheng J. Y., Fu Y. H., Li M. H., Wang J. S., Jia A. Q. (2017). H-1 NMR-based global metabolic studies of Pseudomonas aeruginosa upon exposure of the quorum sensing inhibitor resveratrol. J. Proteome Res. 16 824–830. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong J., Soufan O., Li C., Caraus I., Li S., Bourque G., et al. (2018). MetaboAnalyst 4.0: towards more transparent and integrative metabolomics analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 W486–W494. 10.1093/nar/gky310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI] (2018). M100 S28 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Wayne, PA: Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Coniglio M. A., Ferrante M., Yassin M. H. (2018). Preventing Healthcare-associated legionellosis: results after 3 years of continuous disinfection of hot water with monochloramine and an effective water safety plan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15:E1594. 10.3390/ijerph15081594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornea C. P. A., Roming F. I., Sicuia O. A., Voaides C., Zamfir M., Grosu-Tudor S. S. (2016). Biosurfactant production by Lactobacillus spp. strains isolated from Romanian traditional fermented food products. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 21 11312–11320. [Google Scholar]

- Cosquer A., Ficamos M., Jebbar M., Corbel J. C., Choquet G., Fontenelle C., et al. (2004). Antibacterial activity of glycine betaine analogues: involvement of osmoporters. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 14 2061–2065. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.02.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Giglio O., Napoli C., Lovero G., Diella G., Rutigliano S., Caggiano G., et al. (2015). Antibiotic susceptibility of Legionella pneumophila strains isolated from hospital water systems in Southern Italy. Environ. Res. 142 586–590. 10.1016/j.envres.2015.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai J. D., Banat I. M. (1997). Microbial production of surfactants and their commercial potential. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61 47–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederen B. M. W. (2008). Legionella spp. and Legionnaires’ disease. J. Infect. 56 1–12. 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykes G. A. (1995). Bacteriocins: ecological and evolutionary significance. Trends Ecol. Evol. 10 186–189. 10.1016/s0169-5347(00)89049-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foschi C., Laghi L., D’Antuono A., Gaspari V., Zhu C., Dellarosa N., et al. (2018). Urine metabolome in women with Chlamydia trachomatis infection. PLoS One 13:e0194827. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foschi C., Laghi L., Parolin C., Giordani B., Compri M., Cevenini R., et al. (2017). Novel approaches for the taxonomic and metabolic characterization of lactobacilli: integration of 16S rRNA gene sequencing with MALDI-TOF MS and 1H-NMR. PLoS One 12:e0172483. 10.1371/journal.pone.0172483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuochi V. (2016). Amensalistic activity of Lactobacillus spp. isolated from human samples. Catania: Università degli Studi di Catania. [Google Scholar]

- Fuochi V., Cardile V., Petronio Petronio G., Furneri P. M. (2018). Biological properties and production of bacteriocins-like-inhibitory substances by Lactobacillus spp. strains from human vagina. J. Appl. Microbiol. 126 1541–1550. 10.1111/jam.14164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuochi V., Li Volti G., Furneri P. M. (2017). Probiotic properties of lactobacillus fermentum strains isolated from human oral samples and description of their antibacterial activity. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 18 138–149. 10.2174/1389201017666161229153530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuochi V., Petronio G. P., Lissandrello E., Furneri P. M. (2015). Evaluation of resistance to low pH and bile salts of human Lactobacillus spp. isolates. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 28 426–433. 10.1177/0394632015590948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam N., Sharma N. (2009). Purification and characterization of bacteriocin produced by strain of Lactobacillus brevis MTCC 7539. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 46 337–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge J., Sun Y., Xin X., Wang Y., Ping W. (2016). Purification and partial characterization of a novel bacteriocin synthesized by Lactobacillus paracasei HD1-7 isolated from Chinese Sauerkraut Juice. Sci. Rep. 6:19366. 10.1038/srep19366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata T., Tanaka R., Ohmomo S. (2010). Isolation and characterization of plantaricin ASM1: a new bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus plantarum A-1. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 137 94–99. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hechard Y., Ferraz S., Bruneteau E., Steinert M., Berjeaud J. M. (2005). Isolation and characterization of a Staphylococcus warneri strain producing an anti-Legionella peptide. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 252 19–23. 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.03.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtsma P. C., de Wit J. C., Rombouts F. M. (1993). Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of sodium lactate for pathogens and spoilage organisms occurring in meat products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 20 247–257. 10.1016/0168-1605(93)90169-h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu B. M., Huang C. C., Chen J. S., Chen N. H., Huang J. T. (2011). Comparison of potentially pathogenic free-living amoeba hosts by Legionella spp. in substrate-associated biofilms and floating biofilms from spring environments. Water Res. 45 5171–5183. 10.1016/j.watres.2011.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joondan N., Jhaumeer-Laulloo S., Caumul P. (2014). A study of the antibacterial activity of L-Phenylalanine and L-Tyrosine esters in relation to their CMCs and their interactions with 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine. DPPC as model membrane. Microbiol. Res. 169 675–685. 10.1016/j.micres.2014.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen P. E., Persson C., Fuochi V., Pedersen A., Karlsson B. G., Nissen-Meyer J., et al. (2016). NMR structure and mutational analysis of the lactococcin A immunity protein. Biochemistry 55 6250–6257. 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laghi L., Picone G., Cruciani F., Brigidi P., Calanni F., Donders G., et al. (2014). Rifaximin modulates the vaginal microbiome and metabolome in women affected by bacterial vaginosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 3411–3420. 10.1128/AAC.02469-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Guennec A., Tayyari F., Edison A. S. (2017). Alternatives to nuclear overhauser enhancement spectroscopy presat and carr-purcell-meiboom-gill presat for NMR-based metabolomics. Anal. Chem. 89 8582–8588. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b02354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. L., Cesario T., Owens J., Shanbrom E., Thrupp L. D. (2002). Antibacterial activity of citrate and acetate. Nutrition 18 665–666. 10.1016/s0899-9007(02)00782-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiseau C., Schlusselhuber M., Bigot R., Bertaux J., Berjeaud J. M., Verdon J. (2015). Surfactin from Bacillus subtilis displays an unexpected anti-Legionella activity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99 5083–5093. 10.1007/s00253-014-6317-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna J. M., Rufino R. D., Sarubbo L. A., Campos-Takaki G. M. (2013). Characterisation, surface properties and biological activity of a biosurfactant produced from industrial waste by Candida sphaerica UCP0995 for application in the petroleum industry. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 102 202–209. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhu A. N., Prapulla S. G. (2014). Evaluation and functional characterization of a biosurfactant produced by Lactobacillus plantarum CFR 2194. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 172 1777–1789. 10.1007/s12010-013-0649-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meylheuc T., Renault M., Bellon-Fontaine M. N. (2006). Adsorption of a biosurfactant on surfaces to enhance the disinfection of surfaces contaminated with Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 109 71–78. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministero della Salute (2016). Linee Guida per la Prevenzione ed il Controllo Della Legionellosi. Rome: Ministero della Salute. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D. L., Cox M. M., Lehninger A. L. (2017). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. New York, NY: Macmillan Higher Education. [Google Scholar]

- Oh D. H., Marshall D. L. (1993). Antimicrobial activity of ethanol, glycerol monolaurate or lactic acid against Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 20 239–246. 10.1016/0168-1605(93)90168-g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolin C., Foschi C., Laghi L., Zhu C. L., Banzola N., Gaspari V., et al. (2018). Insights into vaginal bacterial communities and metabolic profiles of chlamydia trachomatis infection: positioning between eubiosis and dysbiosis. Front. Microbiol. 9:600. 10.3389/Fmicb.2018.00600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz F. O., Gerbaldo G., Garcia M. J., Giordano W., Pascual L., Barberis I. L. (2012). Synergistic effect between two bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances produced by Lactobacilli strains with inhibitory activity for Streptococcus agalactiae. Curr. Microbiol. 64 349–356. 10.1007/s00284-011-0077-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D., Saharan B. S. (2016). Functional characterization of biomedical potential of biosurfactant produced by Lactobacillus helveticus. Biotechnol. Rep. 11 27–35. 10.1016/j.btre.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A., Van Hamme J. D., Ward O. P. (2007). Surfactants in microbiology and biotechnology: Part 2. Application aspects. Biotechnol. Adv. 25 99–121. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2006.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanojevic-Nikolic S., Dimic G., Mojovic L., Pejin J., Djukic-Vukovic A., Kocic-Tanackov S. (2016). Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid against pathogen and spoilage microorganisms. J. Food Process. Preserv. 40 990–998. 10.1111/jfpp.12679 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tahmourespour A., Salehi R., Kasra Kermanshahi R. (2011). Lactobacillus acidophilus-derived biosurfactant effect on gtfb and gtfc expression level in Streptococcus mutans biofilm cells. Braz. J. Microbiol. 42 330–339. 10.1590/S1517-83822011000100042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toba T. S., Samant S. K., Yoshioka E., Itoh T. (1991). Reutericin 6, a new bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus reuteri LA 6. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 13 281–286. 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1991.tb00629.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsilingiri K., Rescigno M. (2013). Postbiotics: what else? Beneficial. Microbes. 4 101–107. 10.3920/Bm2012.0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hamme J. D., Singh A., Ward O. P. (2006). Physiological aspects. Part 1 in a series of papers devoted to surfactants in microbiology and biotechnology. Biotechnol. Adv. 24 604–620. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2006.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velraeds M. M. C., vanderMei H. C., Reid G., Busscher H. J. (1996). Inhibition of initial adhesion of uropathogenic Enterococcus faecalis by biosurfactants from Lactobacillus isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62 1958–1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventrella D., Laghi L., Barone F., Elmi A., Romagnoli N., Bacci M. L. (2016). Age-related 1H NMR characterization of cerebrospinal fluid in newborn and young healthy piglets. PLoS One 11:e0157623. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. J., Chang T., Yang H., Cui M. (2015). Antibacterial mechanism of lactic acid on physiological and morphological properties of Salmonella enteritidis. Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control 47 231–236. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.06.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook A. W., Miscevic D., Kilpatrick S., Bruder M. R., Moo-Young M., Chou C. P. (2018). Strain engineering for microbial production of value-added chemicals and fuels from glycerol. Biotechnol. Adv. 37 538–568. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willey J. M., Sherwood L., Woolverton C. J., Prescott L. M. (2010). Prescott’s Principles of Microbiology. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Jiang H., He Q., Wang M., Xue J., Liu H., et al. (2017). Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry reveals the effect of lactobacillus treatment on the faecal metabolite profile of rats with chronic renal failure. Nephron 135 156–166. 10.1159/000452453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M., Matsuda A., Ichikawa S. (2015). Synthesis of isoxazolidine-containing uridine derivatives as caprazamycin analogues. Org. Biomol. Chem. 13 1187–1197. 10.1039/c4ob02142h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X., Heeney D. D., Srisengfa Y. T., Chen S. Y., Slupsky C. M., Marco M. L. (2018). Sucrose metabolism alters Lactobacillus plantarum survival and interactions with the microbiota in the digestive tract. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 94:fiy084 10.1093/femsec/fiy084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Liu L., Hao Y., Zhong S., Liu H., Han T., et al. (2013). Isolation and partial characterization of a bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus plantarum BM-1 isolated from a traditionally fermented Chinese meat product. Microbiol. Immunol. 57 746–755. 10.1111/1348-0421.12091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.