Abstract

Background

Historically, in the pediatric population, there is a highly selective approach for repeat imaging given the risk of radiation and costs. In the lieu of this, frequent neurological checks and even ICP monitoring has been used as an adjunct, although not always successful. We present a case of a pediatric patient with a late evolving epidural hematoma in the setting of a depressed skull fracture, and present an argument for serial CT imaging in a select patient population similar to his.

Objective

Discuss the unique presentation, diagnosis, and management of an expanding epidural hematoma in a pediatric patient with a depressed skull fracture and the need for aggressive repeat imaging in this setting.

Case report

Patient is a 15-year-old boy who presented to our trauma bay after being the victim of a hit and run while skateboarding. His injuries included a depressed comminuted skull fracture and bilateral SDH. Additionally, a stat CT angiogram was obtained due to a basilar skull fracture. A rapidly evolving EDH with impending herniation was found, which was nearly fatal and was not present on the initial CT scan. He required emergent evacuation with a hemi-craniectomy where he was found to have a laceration of his dural vessels as well as his middle meningeal artery. Post operatively he did well and regained full neurologic function.

Conclusion

We presented a case of a pediatric patient with a late evolving epidural hematoma seen on repeat CT imaging. In the setting of a depressed skull fracture, hemorrhage from this source is likely to be missed on initial CT imaging. Frequent neurochecks or ICP monitoring may not be possible in this population encouraging the need for more aggressive repeat imaging.

Introduction

In the pediatric population, traumatic brain injury remains the leading cause of permanent disability and death [10]. The Center for Disease Control has reported that on average 12,175 children die each year from unintentional trauma, of which 2685 are from traumatic brain injury alone. While the mechanism varied depending on age, consensus guidelines on traumatic brain injury in pediatric TBI have been an area of ongoing research due to this significant epidemiology. Historically, there has been a highly selective approach for CT imaging in the pediatric trauma patient with suspected TBI. The most recent literature suggests that a majority of head CT scans in the blunt trauma pediatric patient are unnecessary and should be guided by a strict selective approach guided by neurologic changes [1]. In the lieu of imaging, ICP monitoring has also been used as an adjunct to detect changes in cerebral edema and bleeding. However, despite Brain Trauma Foundation guidelines, there is limited survival benefit in pediatric patients with blunt head trauma [7].

The need for serial CT imaging in this patient population has also been studied before but is not well established. The literature has shown that in the setting of severe TBI (GCS <9) or presence of EDH >10 cc, serial imaging is justified and could alter management [8,9]. In patients presenting with a depressed skull fracture, there is a gap in the literature pertaining to repeat imaging. While a majority of skull fractures can be managed conservatively, depressed skull fractures typically have a lower threshold for surgery, especially when an associated hematoma is visualized and requires evacuation [10]. We present a case of a pediatric patient with a late evolving epidural hematoma in the setting of a depressed skull fracture. This was an injury not encountered on the initial CT scan and would have been missed had a serial CT not been performed. We argue for a higher clinical index of suspicion and more aggressive serial CT imaging in the setting of depressed skull fractures.

Case report

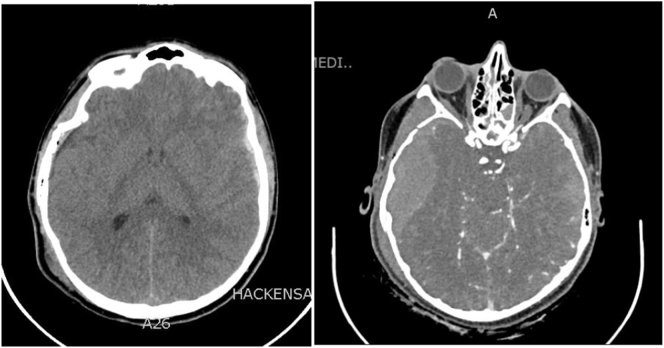

Our patient is a 15-year-old boy who was the victim of a hit and run accident while on his skateboard. He was unresponsive in the field with multiple injuries including a deformed left upper extremity and a tension pneumothorax requiring needle decompression. He was emergently brought to our trauma center and stabilized. Initial CT head showed a small right subdural hematoma with contralateral left-sided subdural hematoma as well as multiple temporal contusions with a depressed temporal skull fracture that communicated with a basilar skull fracture. The patient at this time was agitated however localizing with a GCS of 7T. Given the basilar skull fractures, the patient underwent a CT Angiogram of the brain a couple hours after the initial CT scan which showed a 3.5 cm newly expanding right-sided epidural hematoma warranting emergent evacuation (Fig. 1). This finding was not appreciated on the initial scan. Shortly before operative intervention, the patient became bradycardic, hypertensive and tachypnic; signs of impending herniation. Intra-operatively, he was found to have a significant right-sided comminuted skull fracture extending from the temporal fossa to the basilar skull. A hemi-craniectomy was performed and a large laceration was noted to the dural vessels as well as the middle meningeal artery. The epidural hematoma at this point was causing severe mass effect, which would have been fatal had subsequent imaging not been performed. Post operatively he was taken to the Pediatric ICU. He was weaned off sedation and extubated several days later, noted to be neurologically intact with a GCS of 15. He worked well with the physical, occupational, and cognitive therapy services and was medically stabilized for transfer to a rehab center.

Fig. 1.

Interval CTA performed 2 h after CT head showing dramatic evolution of epidural hematoma.

Discussion

Historically, there is a highly selective approach for repeat CT imaging in the pediatric population. Given the risks of radiation exposure and additional costs, the stigma remains true today and is supported by even the most recent literature [1,2,5]. The clinical practice pattern for skull fractures in general remains fairly conservative. A majority of these patients are discharged home safely from the ED [5]. Depressed skull fractures, however, typically have a more formidable clinical course. They typically have a lower threshold for surgery, especially when an associated hematoma is visualized and requires evacuation [3,4,10]. In the patient not requiring emergent surgery, the role of expeditious repeat imaging is not well established or encouraged. In the current literature, the majority of follow up CT scans prompted by neurologic changes have only been found to prolong intensive care unit stay without change in mortality or change in management [1]. Our patient differs clinically in that he had a comminuted depressed skull fracture in the temporal fossa near the middle meningeal artery. In the setting of blunt trauma, a calvarial fracture with associated intracranial injury is not uncommon, however, the evolution of extra-axial hemorrhages is not always seen or easily predictable [6]. While CT imaging plays an essential role in management of these particular patients, there is currently no support in the literature to suggest expeditious repeat imaging in this population.

There are several risk factors that can be linked to worse outcomes in the setting of depressed skull fractures. These predictors include GCS score on presentation, site of the fracture, and fracture type [4]. Fractures involving more than one area, and those associated with other intracranial injuries have also been shown to worsen outcome and increase the need for surgical intervention [3,4]. The current standard in patients with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury is a follow-up CT scan of the head within 24 h of admission [1], however, this is a critical time frame where acute injuries could blossom and go unrecognized. There is also literature supporting the efficacy of frequent neurological examinations and serial GCS scoring in lieu of imaging [1]. Unfortunately, our patient had no neurologic changes. Furthermore with the added component of medications for sedation and pain control, these indicators become are extremely limited in a realistic setting. There is also the added subjective variable of neurologic exams performed by different providers.

Another alternative to imaging has been ICP monitoring. The role of ICP as an adjunct in a patient with severe TBI has been used to detect changes in cerebral edema and bleeding [7]. In contrast to ICP monitoring, CT imaging offers the advantage of localizing the bleed. An increase in ICP in our patient whether demonstrated neurologically or by an ICP monitor, would have failed to show us the location for therapy. Additionally in our patient, an ICP monitor was not an option given the bilateral extra-axial hemorrhages and multiple skull fractures. An alternative approach may be XR of the skull for serial imaging however this is an area in need of further research.

The argument against repeat imaging has been the risk of radiation and the costs. The national cancer institute has cited epidemiologic studies to show that children are more sensitive to radiation than adults and have a longer window of opportunity for expressive the damage done by radiation. They reported a cumulative dose of 50-60 mGy (equivalent to about two head CT scans) to the brain would increase the risk of brain tumors by about three-fold. In regards to cost, the American College of Radiology has reported that the average cost of a non-contrast head CT is about $1390 at an academic facility. These arguments against CT examinations should always be looked at and incorporated in clinical decision making on a case by case basis. However, in a patient setting similar to ours, the risk of death and long term disability greatly outweigh these costs.

Conclusion

We presented a case of a pediatric patient with a late evolving epidural hematoma seen on repeat CT imaging. In the setting of a depressed skull fracture, hemorrhage from this source can be missed on initial CT imaging. Frequent neurochecks and ICP monitoring may not be possible in this population, supporting the need for more aggressive repeat imaging.

References

- 1.Hill E.P., Stiles P., Reyes J., Nold R.J., Helmer S.D., Haan J.M. Repeat head imaging in blunt pediatric trauma patients. Is it necessary? J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82(5):896–900. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanley R.M., Johnson M., Vanc C., Bajaj L., Babcock L. Challenges enrolling children into traumatic brain injury trials: an observational study. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016;24(1):31–39. doi: 10.1111/acem.13085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tunik M.G., Powell E.C., Mahajan P., Schunk J.E., Jacobs E. Clinical presentations and outcomes of children with basilar skull fractures after blunt head trauma. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2016;68(4):431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritesh S.S., Srikant B., Jayashree P., Rajesh M. Analysis of factors influencing outcome of depressed fracture of the skull. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2018;13(2):341–347. doi: 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_117_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackwood B., Bean J., Sadecki-Lund C., Helenowski I., Kabre R., Hunter C. Observation for isolated traumatic skull fractures in the pediatric population: unnecessary and costly. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2016;51(4):654–658. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Brien W.T., Care M.M., Leach J. Pediatric emergencies: imaging of pediatric head trauma. Semin. Ultrasound CT MRI. 2018;39(4):323–335. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogseth M. Intracranial pressure monitoring in children with severe traumatic brain injury national trauma data bank–based review of outcomes. J. Emerg. Med. 2014;47(4):505–506. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bata S., Yung M. Role of routine repeat head imaging in paediatric traumatic brain injury. ANZ J. Surg. 2014;84(6):438–441. doi: 10.1111/ans.12582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim W., Lim D., Kim S., Ha S., Choi J., Kim S. Is routine repeated head CT necessary for all pediatric traumatic brain injury? J. Kor. Neurosurg. Soc. 2015;58(2):125. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2015.58.2.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Araki T., Yokota H., Morita A. Pediatric traumatic brain injury: characteristic features, diagnosis, and management. Jpn. Neurosurg. Soc. 2017;57(2):82–93. doi: 10.2176/nmc.ra.2016-0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]