Abstract

As a key component of the Wnt signaling pathway, the β-catenin-transcription factor 7 like 1 (TCF7L1) complex activates transcription and regulates downstream target genes that serve important roles in the pathology of pancreatic cancer. To identify associated key genes and pathways downstream of the β-catenin-TCF7L1 complex in pancreatic cancer cells, the current study used the gene expression profiles GSE57728 and GSE90926 downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus. GSE57728 is an array containing information regarding β-catenin knockdown and GSE90926 was developed by high throughput sequencing to provide information regarding TCF7L1 knockdown. Subsequently, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were sorted separately and the shared 88 DEGs, including 37 upregulated and 51 downregulated genes, were screened. Clustering analysis of these DEGs was performed by heatmap analysis. Functional and pathway enrichment analyses were then performed using FunRich software and Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery, which revealed that the DEGs were predominantly enriched in terms associated with transport, transcription factor activity, and cytokine and chemokine mediated signaling pathway process. A DEG-associated protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, consisting of 58 nodes and 171 edges, was then constructed using Cytoscape software and the 15 genes with top node degrees were selected as the hub genes. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the 88 DEGs was performed and the relevant gene expression datasets were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas. Consequently, three upregulated and seven downregulated genes were identified to be associated with prognosis. Furthermore, high expression levels of five downregulated genes, including CXCL5, CYP27C1, FUBP1, CDK14 and TRIM24, were associated with worse OS. In addition, CDK14 and TRIM24 were revealed as hub genes in the PPI network and both were confirmed to be involved in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. Promoter analysis was also applied to the five downregulated DEGs associated with prognosis, which revealed that TCF7L1 may serve as a transcription factor of the DEGs. In conclusion, the genes and pathways identified in the current study may provide potential targets for the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, transcription factor 7 like 1, β-catenin, differentially expressed genes, potential targets

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is a highly malignant tumor type of the digestive tract that is ranked as the fourth leading cause of cancer-associated mortality (1), with an estimated 55,440 new cases and an estimated 44,330 mortalities in the USA in 2018 according to statistics from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (2). Its aggressive biological properties, lack of early symptoms and rapid spread to surrounding organs lead are responsible for the high mortality rate (3). Furthermore, the treatment of pancreatic cancer is limited due to difficulties associated with surgical removal, and poor sensitivity to radiotherapy and chemotherapy (4–6). Therefore, identification of therapeutic targets is urgently required to improve patient outcome (7).

It has been reported that β-catenin, a versatile protein that mediates intercellular adhesion and gene expression, is abnormally expressed in pancreatic cancer (8). As the transcriptional cofactor of β-catenin, transcription factor 7 like 1 (TCF7L1), also termed transcription factor 3, is a member of the mammalian TCF/LEF family. Nuclear DNA-binding TCF/LEF proteins and β-catenin represent key components of the canonical branch of the Wnt signaling pathway, which serves a key role in pancreatic cancer carcinogenesis (9,10).

Once the Wnt pathway is activated, β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm and enters the nucleus, where it engages DNA-bound TCF transcription factors and subsequently regulates the transcription of downstream target genes (11). It is understood that β-catenin and TCF7L1 are pivotal proteins in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway; therefore, the genes they regulate may be drug targets for pancreatic cancer (12).

In recent years, microarray and high throughput sequencing technologies have widely been used to explore the genetic characteristics of tumorigenesis, which may promote the development of diagnostic and treatment strategies (13). Bioinformatics research methods are required to handle large sample data; therefore, different databases have been established to provide convenience for research (14,15). In the present study, the gene expression profiles GSE57728, an array focused on β-catenin, and GSE90926, an array developed by high throughput sequencing regarding TCF7L1, were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and analyzed to obtain the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between pancreatic control groups and experimental groups. Clustering analysis, and functional and pathways enrichment analysis were performed to identify the associations and functions of the DEGs. In addition, a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed, and overall survival (OS) and promoter analyses was performed, to identify the associated key genes and pathways downstream of the β-catenin-TCF7L1 complex in pancreatic cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Collection and inclusion criteria of the studies

The GEO database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) was searched for the following keywords: ‘pancreatic cancer’ (study keyword), ‘β-catenin’ (study keyword), ‘Homo sapiens’ (organism) and ‘Expression profiling by array or sequencing’ (study type). This search revealed seven studies. The inclusion criteria for the studies were as follows: i) Samples were required to be in two groups, including the control group and the experimental group, ii) the sample count needed to be >10, iii) β-catenin or TCF7L1 in the experimental group should be overexpressed or inhibited, and iv) sufficient information had to be present to perform the analysis. Consequently, GSE57728 (16) was downloaded for analysis regarding β-catenin and GSE90926, which was contributed by Dr David Dawson (Dawson Laboratory, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA), was downloaded for analysis regarding TCF7L1.

Microarray data and validation

Two gene expression profiles (GSE57728 and GSE90926) were downloaded from the GEO database. The array data regarding β-catenin knockdown in GSE57728 included 16 samples, from this the present study selected two control samples with control small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection and two experimental samples with β-catenin siRNA transfection for analysis. Similarly, the sequencing data regarding TCF7L1 knockdown in GSE90926 included 12 samples and the current study selected three control samples with control siRNA transfection and three experimental samples with TCF7L1 siRNA transfection for further analysis. Subsequently, a microarray assay regarding β-catenin knockdown was conducted to confirm the results from the microarray data downloaded from the GEO database. This was performed based on previous studies in which relevant results regarding the Wnt pathway in pancreatic cancer were revealed, including the identification of FH535 as a small-molecule inhibitor of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (10,17). FH535, as a classic inhibitor of the β-catenin pathway which could repress pancreatic cancer cell growth and metastasis, played the same role as siRNA in the inhibition of the β-catenin pathway. Sample preparation and processing were performed as described in the GeneChip Expression Analysis Manual (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Differentially expressed genes were screened using Agilent 44K human whole-genome oligonucleotide microarrays (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). After obtaining the two completed microarrays with different gene expressions, 10 shared genes were selected randomly and the gene expression levels of the control and experimental groups were compared to confirm that the data downloaded from the GEO database was reliable.

Data processing

R (version 3.3.3 for Windows; https://www.r-project.org/) is a software system used for data processing, computing and mapping based on the different R packages. The limma package was used to identify the DEGs by linear modeling of the genes. P<0.05 and a fold change >1.5 or <0.667 were set as the cut-off criteria. Subsequently, a heat map of DEGs was generated using R and P<0.05 was set as the cut-off criterion.

Functional and pathway enrichment analysis, and PPI network construction

Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) provides a comprehensive set of functional annotation tools for investigators to understand the biological meaning behind a large list of genes. FunRich is a stand-alone software tool used predominantly for functional enrichment and interaction network analysis of genes and proteins. The results of the analysis can be depicted graphically in the form of Venn, bar, column, pie and doughnut charts. In the present study, gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed for the identified DEGs using the FunRich (version 3.1.3 for Windows; http://www.funrich.org/) and DAVID databases (version 6.8; http://david.ncifcrf.gov/). P<0.05 was set as the cut-off criterion, however, for the sake of symmetry and sharp contrast, the P-value of several terms was >0.05. In every figure, eight columns were sorted using Funrich. Pathway enrichment analysis was performed for the identified DEGs using KOBAS (http://kobas.cbi.pku.edu.cn/), which is a web server for gene/protein functional annotation and functional gene set enrichment. In addition, the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; http://www.kegg.jp/) database was used, which is an integrated database resource for biological interpretation of genome sequences and other high-throughput data (18). P<0.05 was set as the cut-off criterion. In addition, a PPI network of the DEGs was constructed using the STRING database (http://string-db.org/) and Cytoscape (version 3.7.1 for Windows; http://cytoscape.org/), which is a commonly used software to generate integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. A combined score >0.15 was set as the cut-off criterion. To screen the hub genes, a node degree ≥8 was set as the cut-off criterion.

Survival analysis of DEGs

Gene expression datasets were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; http://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga) to analyze the prognosis of target DEGs. Data from a total of 178 patients with complete clinicopathological and RNASeq data were collected from the TCGA pancreatic cancer cohort. Clinical characteristics of the 178 patients are presented in Table I, including case ID, sex, year of birth, year of mortality, tumor stage, age at diagnosis measured in days, vital status and time from diagnosis to the last follow-up date or mortality. The patients were divided into two groups according to the expression of a particular gene, including a high expression group and a low expression group. The OS of patients with pancreatic cancer was analyzed using R software and the results were compared using Kaplan-Meier curves on which the P-value was presented. A log-rank test was conducted as the post hoc test.

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of 178 patients used for overall survival analysis.

| Case ID | Sex | Year of birth | Year of mortality | Tumor stage | Age at diagnosis, days | Alive at last follow-up | Days from diagnosis to mortality | Days from diagnosis to last follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 1929 | 2011 | iib | 30,092 | No | 292 | – |

| 2 | Female | 1942 | – | iIb | 26,179 | No | 375 | 1 |

| 3 | Male | 1970 | – | iib | 15,807 | Yes | – | 286 |

| 4 | Male | 1938 | – | ib | 27,362 | No | 498 | 449 |

| 5 | Female | 1953 | – | iia | 22,131 | Yes | – | 438 |

| 6 | Male | 1947 | 2012 | iib | 23,962 | No | 66 | – |

| 7 | Male | 1938 | 2013 | iib | 27,082 | No | 652 | – |

| 8 | Female | 1938 | 2014 | iib | 27,662 | No | 532 | – |

| 9 | Male | 1972 | – | ia | 14,729 | Yes | – | 1,037 |

| 10 | Male | 1932 | – | iib | 29,792 | Yes | – | 483 |

| 11 | Male | 1932 | – | ib | 29,631 | Yes | – | 7 |

| 12 | Female | 1938 | – | iib | 27,645 | Yes | – | 525 |

| 13 | Female | 1962 | – | iib | 18,202 | No | 913 | 648 |

| 14 | Male | 1962 | – | iib | 18,357 | Yes | – | 920 |

| 15 | Male | 1949 | – | iib | 23,152 | Yes | – | 666 |

| 16 | Male | 1926 | 2010 | iia | 29,633 | No | 1,101 | – |

| 17 | Female | 1957 | 2012 | iib | 20,051 | No | 511 | – |

| 18 | Male | 1936 | 2009 | iib | 26,085 | No | 1,059 | – |

| 19 | Female | 1946 | – | ib | 23,406 | Yes | – | 1,542 |

| 20 | Male | 1957 | 2013 | iib | 20,133 | No | 607 | – |

| 21 | Male | 1941 | – | iib | 24,760 | Yes | – | 2,285 |

| 22 | Female | 1940 | – | iib | 26,635 | No | 732 | 385 |

| 23 | Male | 1943 | – | ib | 24,621 | Yes | – | 998 |

| 24 | Male | 1933 | – | iib | 28,174 | No | 661 | 240 |

| 25 | Female | 1936 | – | iib | 24,025 | No | 2,036 | 1,953 |

| 26 | Male | 1937 | – | iib | 27,453 | Yes | – | 743 |

| 27 | Male | 1965 | 2012 | iib | 17,294 | No | 308 | – |

| 28 | Female | 1955 | – | iib | 20,741 | Yes | – | 392 |

| 29 | Female | 1930 | 2011 | iib | 29,585 | No | 153 | – |

| 30 | Male | 1964 | – | iib | 17,794 | Yes | – | 729 |

| 31 | Female | 1947 | – | iv | 24,291 | Yes | – | 420 |

| 32 | Male | 1925 | 2009 | iia | 30,571 | No | 480 | – |

| 33 | Female | 1932 | – | iii | 29,213 | Yes | – | 462 |

| 34 | Female | 1948 | – | iib | 23,672 | Yes | – | 635 |

| 35 | Male | 1964 | – | iib | 18,059 | Yes | – | 404 |

| 36 | Male | 1938 | – | iia | 27,684 | No | 267 | 110 |

| 37 | Female | 1936 | – | iib | 27,929 | No | 517 | 0 |

| 38 | Female | 1952 | – | ib | 21,732 | Yes | – | 1,103 |

| 39 | Male | 1941 | – | iib | 26,028 | Yes | – | 80 |

| 40 | Female | 1939 | – | iia | 27,152 | Yes | – | 467 |

| 41 | Female | 1946 | – | iib | 22,981 | Yes | – | 228 |

| 42 | Female | 1942 | 2013 | iib | 25,920 | No | 627 | – |

| 43 | Male | 1946 | 2012 | iib | 23,998 | No | 458 | – |

| 44 | Female | 1929 | 2011 | iib | 29,904 | No | 568 | – |

| 45 | Female | 1959 | – | iib | 19,064 | No | 593 | 20 |

| 46 | Female | 1928 | – | ia | 30,821 | No | 151 | 91 |

| 47 | Male | 1958 | – | iib | 19,904 | Yes | – | 767 |

| 48 | Female | 1946 | – | iib | 23,868 | No | 596 | 21 |

| 49 | Male | 1952 | – | iib | 21,676 | Yes | – | 522 |

| 50 | Female | 1947 | 2009 | iib | 22,990 | No | 110 | – |

| 51 | Female | 1958 | – | iia | 19,839 | No | 299 | 28 |

| 52 | Male | 1936 | – | iib | 27,637 | Yes | – | 194 |

| 53 | Female | 1945 | 2010 | iib | 23,953 | No | 31 | – |

| 54 | Male | 1939 | 2013 | iib | 26,936 | No | 691 | – |

| 55 | Female | 1948 | – | iib | 22,376 | Yes | – | 2,016 |

| 56 | Male | 1939 | – | ia | 26,947 | Yes | – | 454 |

| 57 | Male | 1943 | 2011 | iib | 24,078 | No | 1,130 | – |

| 58 | Female | 1951 | – | iia | 22,090 | Yes | – | 840 |

| 59 | Female | 1965 | – | iib | 17,821 | No | 278 | 164 |

| 60 | Female | 1936 | – | iib | 28,434 | No | 160 | 11 |

| 61 | Female | 1945 | 2010 | iib | 23,580 | No | 603 | – |

| 62 | Male | 1926 | 2011 | ia | 31,319 | No | 244 | – |

| 63 | Female | 1968 | – | i | 14,599 | Yes | – | 2,741 |

| 64 | Male | 1954 | – | iib | 19,847 | Yes | – | 716 |

| 65 | Female | 1953 | – | ib | 22,126 | Yes | – | 9 |

| 66 | Male | 1978 | – | iib | 13,127 | Yes | – | 245 |

| 67 | Male | 1947 | – | iia | 24,007 | Yes | – | 586 |

| 68 | Male | 1944 | 2012 | iia | 24,731 | No | 634 | – |

| 69 | Male | 1959 | – | iia | 19,677 | Yes | – | 671 |

| 70 | Male | 1943 | – | iv | 25,849 | Yes | – | 603 |

| 71 | Male | 1937 | – | iib | 27,850 | Yes | – | 0 |

| 72 | Female | 1939 | 2013 | ib | 27,128 | No | 144 | – |

| 73 | Male | 1938 | 2010 | iib | 26,239 | No | 485 | – |

| 74 | Female | 1934 | 2008 | iib | 26,773 | No | 467 | – |

| 75 | Male | 1934 | 2010 | iib | 28,074 | No | 143 | – |

| 76 | Male | 1963 | 2013 | iib | 18,315 | No | 183 | – |

| 77 | Male | 1935 | 2009 | ib | 26,747 | No | 598 | – |

| 78 | Male | 1956 | 2012 | iib | 20,641 | No | 277 | – |

| 79 | Male | 1940 | – | iib | 26,503 | Yes | – | 657 |

| 80 | Male | 1937 | – | iia | 28,047 | Yes | – | 517 |

| 81 | Female | 1968 | – | iib | 16,255 | No | 470 | 247 |

| 82 | Female | 1933 | – | iib | 29,150 | No | 233 | 153 |

| 83 | Male | 1957 | – | iib | 20,071 | No | 592 | 360 |

| 84 | Male | 1945 | – | iib | 24,150 | No | 614 | 361 |

| 85 | Female | 1954 | – | iib | 21,491 | Yes | – | 660 |

| 86 | Male | 1947 | 2011 | iib | 23,713 | No | 216 | – |

| 87 | Female | 1944 | – | iib | 24,891 | Yes | – | 491 |

| 88 | Male | 1962 | 2011 | iib | 18,172 | No | 123 | – |

| 89 | Female | 1946 | – | iv | 24,043 | No | 394 | 347 |

| 90 | Female | 1947 | 2012 | iib | 23,431 | No | 460 | – |

| 91 | Male | 1936 | – | iib | 28,403 | Yes | – | 330 |

| 92 | Female | 1963 | – | iib | 18,607 | No | 366 | 202 |

| 93 | Female | 1956 | – | iia | 20,316 | Yes | – | 969 |

| 94 | Female | 1929 | – | iib | 30,684 | Yes | – | 225 |

| 95 | Female | 1940 | – | iib | 26,379 | Yes | – | 319 |

| 96 | Female | 1939 | – | iib | 27,295 | No | 393 | 127 |

| 97 | Male | 1945 | – | ib | 24,810 | Yes | – | 951 |

| 98 | Female | 1950 | – | iib | 23,218 | No | 313 | 155 |

| 99 | Female | 1950 | – | iib | 22,413 | Yes | – | 4 |

| 100 | Female | 1942 | 2011 | iib | 25,312 | No | 224 | – |

| 101 | Female | 1948 | 2009 | iib | 21,611 | No | 741 | – |

| 102 | Male | 1955 | 2007 | iib | 19,287 | No | 61 | – |

| 103 | Female | 1955 | 2009 | iib | 19,718 | No | 486 | – |

| 104 | Male | 1945 | – | iib | 24,864 | Yes | – | 431 |

| 105 | Male | 1939 | – | iib | 25,809 | Yes | – | 289 |

| 106 | Male | 1950 | – | iib | 22,433 | No | 366 | 24 |

| 107 | Male | 1936 | 2013 | iib | 28,239 | No | 95 | – |

| 108 | Female | 1943 | – | iib | 25,412 | No | 179 | 4 |

| 109 | Female | 1926 | 2012 | iib | 31,393 | No | 481 | – |

| 110 | Male | 1946 | – | iib | 24,589 | Yes | – | 737 |

| 111 | Female | 1933 | 2011 | iib | 28,353 | No | 702 | – |

| 112 | Female | 1958 | – | iib | 20,366 | Yes | – | 33 |

| 113 | Female | 1950 | – | iib | 23,306 | No | 230 | 179 |

| 114 | Male | 1954 | – | iib | 21,024 | No | 518 | 8 |

| 115 | Male | 1945 | 2009 | iia | 23,703 | No | 117 | – |

| 116 | Female | 1922 | 2007 | iib | 31,074 | No | 155 | – |

| 117 | Male | 1950 | – | iia | 22,283 | Yes | – | 1,216 |

| 118 | Female | 1954 | – | iv | 21,501 | No | 545 | 5 |

| 119 | Male | 1931 | 2012 | iib | 29,674 | No | 120 | – |

| 120 | Male | 1957 | – | iia | 20,607 | Yes | – | 498 |

| 121 | Female | 1935 | 2012 | iib | 27,957 | No | 695 | – |

| 122 | Female | 1956 | – | iib | 20,858 | Yes | – | 395 |

| 123 | Female | – | – | iia | 17,628 | Yes | – | 584 |

| 124 | Female | 1949 | 2013 | iib | 23,622 | No | 239 | – |

| 125 | Male | 1934 | – | iia | 28,317 | Yes | – | 482 |

| 126 | Male | 1946 | – | iia | 23,760 | Yes | – | 314 |

| 127 | Male | 1946 | 2010 | iib | 23,443 | No | 12 | – |

| 128 | Male | 1937 | 2009 | iv | 26,216 | No | 619 | – |

| 129 | Male | 1930 | 2010 | iib | 29,319 | No | 123 | – |

| 130 | Female | 1946 | – | ia | 24,174 | Yes | – | 1,021 |

| 131 | Female | 1924 | – | iib | 32,475 | No | 421 | 233 |

| 132 | Male | 1944 | – | ib | 23,791 | Yes | – | 1,854 |

| 133 | Male | 1952 | 2009 | iib | 20,984 | No | 334 | – |

| 134 | Male | 1950 | – | iia | 22,425 | Yes | – | 1,287 |

| 135 | Female | 1951 | – | iib | 22,329 | Yes | – | 289 |

| 136 | Female | 1949 | – | ib | 23,685 | Yes | – | 95 |

| 137 | Male | 1935 | – | iib | 28,454 | No | 308 | 0 |

| 138 | Male | 1946 | – | iib | 24,576 | Yes | – | 338 |

| 139 | Male | 1952 | – | Not reported | 21,175 | Yes | – | 1,794 |

| 140 | Female | 1956 | 2012 | ib | 20,760 | No | 219 | – |

| 141 | Male | 1965 | – | iib | 16,766 | Yes | – | 1,323 |

| 142 | Male | 1970 | – | iib | 15,869 | Yes | – | 440 |

| 143 | Female | 1932 | – | iib | 28,554 | Yes | – | 1,257 |

| 144 | Female | 1943 | – | iib | 25,214 | No | 378 | 16 |

| 145 | Male | 1939 | – | iib | 26,573 | Yes | – | 969 |

| 146 | Male | 1964 | – | iia | 17,649 | No | 353 | 166 |

| 147 | Female | 1955 | – | iib | 21,484 | Yes | – | 463 |

| 148 | Female | 1963 | 2011 | iib | 16,126 | No | 1,502 | – |

| 149 | Male | 1941 | – | iib | 26,188 | Yes | – | 484 |

| 150 | Male | 1955 | 2012 | iib | 20,618 | No | 684 | – |

| 151 | Male | 1937 | 2012 | iia | 27,600 | No | 293 | – |

| 152 | Male | 1942 | – | iia | 25,768 | Yes | – | 252 |

| 153 | Female | 1946 | – | ib | 22,799 | Yes | – | 2,084 |

| 154 | Female | 1940 | – | iia | 26,311 | Yes | – | 232 |

| 155 | Male | 1948 | – | iib | 23,801 | Yes | – | 287 |

| 156 | Male | 1942 | – | iii | 25,227 | Yes | – | 706 |

| 157 | Male | 1967 | 2009 | iib | 15,188 | No | 666 | – |

| 158 | Female | 1938 | – | Not reported | 26,859 | Yes | – | 388 |

| 159 | Male | 1947 | 2007 | iib | 22,148 | No | 145 | – |

| 160 | Male | 1939 | 2013 | iib | 26,745 | No | 430 | – |

| 161 | Male | 1954 | – | Not reported | 20,451 | Yes | – | 1,942 |

| 162 | Male | 1954 | – | iib | 21,792 | Yes | – | 350 |

| 163 | Female | 1928 | 2002 | iii | 26,881 | No | 541 | – |

| 164 | Male | 1962 | 2012 | iia | 18,475 | No | 128 | – |

| 165 | Female | 1942 | 2011 | iia | 24,117 | No | 1,332 | – |

| 166 | Female | 1950 | 2013 | iib | 22,400 | No | 738 | – |

| 167 | Female | 1932 | – | iib | 29,585 | No | 466 | 36 |

| 168 | Male | 1937 | – | iib | 28,013 | Yes | – | 8 |

| 169 | Female | 1949 | – | iia | 23,624 | Yes | – | 379 |

| 170 | Male | 1954 | – | iib | 21,277 | Yes | – | 416 |

| 171 | Female | 1962 | – | iib | 18,129 | Yes | – | 1,116 |

| 172 | Male | 1940 | – | ib | 26,167 | No | 236 | 0 |

| 173 | Female | 1959 | – | ib | 19,707 | Yes | – | 720 |

| 174 | Male | 1958 | – | iib | 19,315 | Yes | – | 1,383 |

| 175 | Male | 1939 | – | iia | 26,943 | Yes | – | 676 |

| 176 | Male | 1941 | – | iib | 26,129 | No | 365 | 329 |

| 177 | Male | 1937 | 2013 | iia | 26,234 | No | 2,182 | – |

| 178 | Male | 1940 | – | iib | 26,322 | Yes | – | 978 |

Tumor stage was determined according to the 7th Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual (61).

Promoter analysis of DEGs

Ensemble (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html) is an online website that was used to perform promoter analysis of the DEGs. The eligible transcript of every DEG associated with prognosis was selected and then the 3,000 base pairs 5′ upstream were selected as the promoter. Subsequently, the transcription factors (TFs) site analysis function of Genomatix (http://www.genomatix.de/solutions/genomatix-software-suite.html) was used to predict potential TF families and TF binding sites by analyzing the sequence of promoter obtained from Ensemble. Core similarity was set as 1 for an accurate prediction.

Results

Microarray data and validation

As demonstrated in the Fig. 1, ten genes that were shared between the original microarray data downloaded from the GEO database and our own microarray data regarding β-catenin knockdown, including CGN, CNN3, DZIP1, EGR1, FBXL17, MDM2, SRXN1, HMOX1 and TMEM2, were selected to confirm the results from microarray data downloaded from the GEO database. The results obtained for samples with β-catenin siRNA transfection and samples treated with FH535 exhibited consistent trends, with the exception of the results for IL32, HMOX1 and TMEM2.

Figure 1.

Microarray data and validation. Ten shared genes, including CGN, CNN3, DZIP1, EGR1, FBXL17, MDM2, SRXN1, HMOX1 and TMEM2, were selected to confirm the results from microarray data downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. Microarray analysis was performed to detect the expression of genes of samples transfected with 20 nM control siRNA or β-catenin siRNA in the original microarray data downloaded from GEO database. Microarray analysis was also performed to measure the expression of genes in samples treated with 20 µM FH535 in our own microarray data. The data are presented as the means ± standard deviation. *P<0.05 vs. respective control. siRNA, small interfering RNA; KD, knockdown.

Identification of DEGs and clustering analysis

A total of 1,784 DEGs, including, 812 upregulated and 972 downregulated genes, were identified from GSE90926 regarding TCF7L1 knockdown. A total of 2,013 DEGs, including 1,000 upregulated and 1,013 downregulated genes, were identified from GSE57728 regarding β-catenin knockdown. Among these DEGs, 88 DEGs were screened out as shared by the two datasets. The upregulated and downregulated DEGs were considered separately when selecting the shared genes. As a result, 37 upregulated and 51 downregulated DEGs were identified (Fig. 2A and B; Table II). The respective heatmaps of the 88 DEGs were generated by R software (Fig. 2C and D).

Figure 2.

Identification of DEGS. (A and B) Identification of DEGs in the expression profiling TCF7L1 KD dataset GSE90926 and the β-catenin KD dataset GSE57728. A total of 88 shared DEGs were identified, including 37 upregulated and 51 downregulated DEGs. (C and D) Heatmaps of the shared 88 DEGs of the two GSE datasets were generated by R software. Red indicates upregulation and green indicates downregulation. DEG, differentially expressed gene; KD, knockdown; TCF7L1, transcription factor 7 like 1; siRNA, small interfering RNA; Rep, replication.

Table II.

Identification of differentially expressed genes.

| Regulation | Genes name |

|---|---|

| Upregulated | MMP19, OBSL1, KIT, PDSS1, SYT5, KLHL9, KCNT2, PPL, KRT7, FBXL17, SH2D3C, MR1, C10orf54, IL32, FLG-AS1, SLC9A1, TDRP, GPSM3, CGN, FKBP1A-SDCBP2, CASK, WDFY2, SLC35F3, SLC7A2, EBF4, KCTD18, SLITRK6, IRF9, STC1, CLIC3, SLC6A6, CYP1A1, GATSL2, NOTUM, TP53INP1, CACNA2D1, SPOCK3. |

| Downregulated | POLR3G, MNS1, ZMAT1, CXCL5, PMP2, DEPDC1, TRIM24, SRXN1, CYP27C1, GPR180, OSBPL6, DNAI1, DCLRE1A, POLR3B, PCDHGA1, CLUL1, C3orf14, SMC5, EGR1, PDK4, RPS6KA5, CLEC2B, SFXN2, HAGLR, PDCD4, RHEBL1, RRBP1, NFIB, DHX34, UBE2Q2L, EOMES, MDM2, FUBP1, DNAH1, DSTYK, ESX1, TET1, ODF2L, NSD1, SSH2, PTX3, LINC00173, MYCL, TMEM2, GRB14, TNFRSF19, CDK14, FRA10AC1, SOX17, PXYLP1, ZNF618. |

Functional and pathway enrichment analysis, and PPI network construction

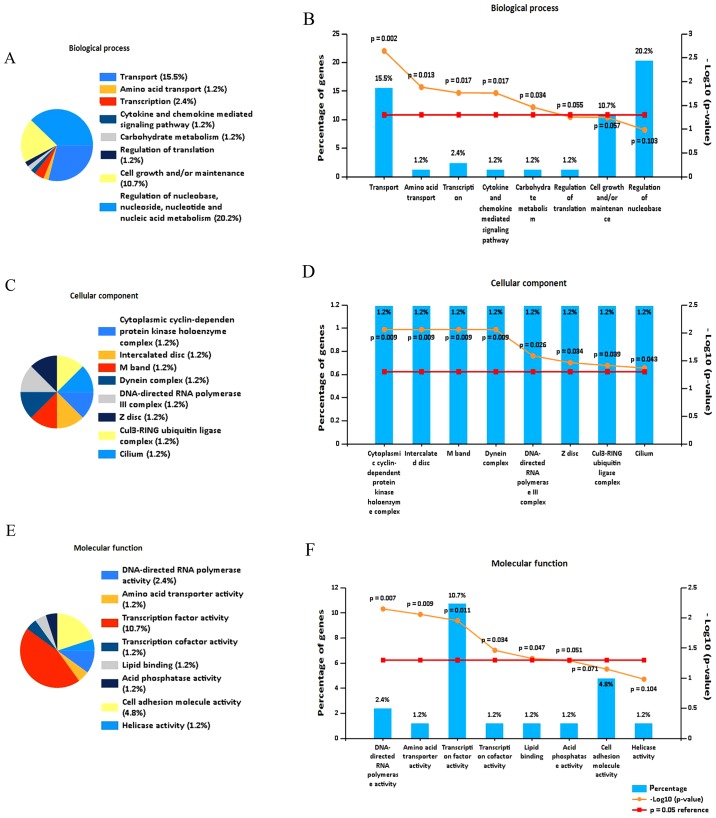

To investigate the function of the DEGs, functional enrichment analysis was performed. Analysis using FunRich software indicated that the DEGs were predominantly enriched in the following biological process terms: Transport, amino acid transport, transcription, cytokine and chemokine mediated signaling pathway, and carbohydrate metabolism (Fig. 3A and B). In addition, the DEGs were predominantly enriched in following cell component terms: Cytoplasmic cyclin-dependent protein kinase holoenzyme complex, interacted disc, M band and DNA-directed RNA polymerase III complex (Fig. 3C and D). Furthermore, for molecular function, the DEGs were enriched in the following terms: Transcription factor activity, DNA-directed RNA polymerase activity, amino acid transporter activity, transcription and lipid binding (Fig. 3E and F).

Figure 3.

Functional and pathway enrichment analysis, and PPI network construction. Functional enrichment analysis of the identified DEGs was performed by FunRich with the following three parts: (A and B) Biological processes, (C and D) cell component and (E and F) molecular function. (G) GO analysis of identified DEGs using Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery. (H) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis of identified DEGs using KOBAS. (I) PPI network of the DEGs consisting of 58 nodes and 171 edges, including 24 upregulated genes (red) and 34 downregulated genes (green). PPI, protein-protein interaction; DEG, differentially expressed gene; GO, gene ontology.

Using the DAVID database, GO analysis identified that the DEGs were enriched in the following terms: Negative regulation of myofibroblast differentiation, stem cell population maintenance and cellular response to antibiotic (Fig. 3G; Table III).

Table III.

GO analysis of differentially expressed genes in pancreatic cancer.

| Category | Term | Count | % | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:1904761~negative regulation of myofibroblast differentiation | 2 | 2.272727273 | 0.009268837 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0019827~stem cell population maintenance | 3 | 3.409090909 | 0.02259656 |

| GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | GO:0002039~p53 binding | 3 | 3.409090909 | 0.033191281 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0071236~cellular response to antibiotic | 2 | 2.272727273 | 0.036569485 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0001706~endoderm formation | 2 | 2.272727273 | 0.054355943 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0003351~epithelial cilium movement | 2 | 2.272727273 | 0.058751666 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0071391~cellular response to estrogen stimulus | 2 | 2.272727273 | 0.058751666 |

| GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | GO:0000977~RNA polymerase II regulatory region sequence-specific DNA binding | 4 | 4.545454545 | 0.059249025 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0070498~interleukin-1-mediated signaling pathway | 2 | 2.272727273 | 0.063127217 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0006885~regulation of pH | 2 | 2.272727273 | 0.071818168 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0090280~positive regulation of calcium ion import | 2 | 2.272727273 | 0.071818168 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0071456~cellular response to hypoxia | 3 | 3.409090909 | 0.07344514 |

| GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | GO:0001056~RNA polymerase III activity | 2 | 2.272727273 | 0.074087687 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005666~DNA-directed RNA polymerase III complex | 2 | 2.272727273 | 0.079265755 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0045089~positive regulation of innate immune response | 2 | 2.272727273 | 0.08042952 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0002690~positive regulation of leukocyte chemotaxis | 2 | 2.272727273 | 0.08042952 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0045892~negative regulation of transcription, DNA-templated | 6 | 6.818181818 | 0.082369804 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0045944~positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | 9 | 10.22727273 | 0.084587325 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0036126~sperm flagellum | 2 | 2.272727273 | 0.087239628 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0006366~transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | 6 | 6.818181818 | 0.090139483 |

P<0.05 was set as the cut-off criterion. Count, the number of enriched genes in each term; GO, gene ontology; BP, biological processes; CC, cell component; MF, molecular function.

KEGG pathway analysis using KOBAS revealed that the DEGs were significantly enriched in the following terms: RNA polymerase, Wnt signaling pathway and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction (Fig. 3H; Table IV).

Table IV.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes signaling pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in pancreatic cancer.

| Pathway ID | Term | Count | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| hsa03020 | RNA polymerase | 2 | 0.002583461 |

| hsa05219 | Bladder cancer | 2 | 0.004105174 |

| hsa04261 | Adrenergic signaling in cardiomyocytes | 3 | 0.004711319 |

| hsa04623 | Cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway | 2 | 0.009436485 |

| hsa05169 | Epstein-Barr virus infection | 3 | 0.010969532 |

| hsa05205 | Proteoglycans in cancer | 3 | 0.011112587 |

| hsa04260 | Cardiac muscle contraction | 2 | 0.013627503 |

| hsa04060 | Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 3 | 0.021708158 |

| hsa00240 | Pyrimidine metabolism | 2 | 0.023537332 |

| hsa04668 | TNF signaling pathway | 2 | 0.025617518 |

| hsa04919 | Thyroid hormone signaling pathway | 2 | 0.029094794 |

| hsa05206 | MicroRNAs in cancer | 3 | 0.029496436 |

| hsa04120 | Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis | 2 | 0.038049532 |

| hsa04530 | Tight junction | 2 | 0.039046349 |

| hsa04310 | Wnt signaling pathway | 2 | 0.041069627 |

| hsa00900 | Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis | 1 | 0.049591361 |

P<0.05 was set as the cut-off criterion. Count, the number of enriched genes in each term.

The PPI network of DEGs consisted of 58 nodes and 171 edges, including 24 upregulated genes and 34 downregulated genes (Fig. 3I). As aforementioned, the shared 88 DEGs sorted from the two GSE datasets included 37 upregulated and 51 downregulated genes; however, all shared DEGs were not included in the PPI network as certain genes that were isolated at the edge were removed. Therefore, as presented in Fig. 3I, 58 shared DEGs were included in the PPI network, in which the red nodes represent the upregulated genes and the green nodes represent the downregulated genes. Furthermore, the most significant hub genes were selected as those with the highest numbers of edges. A total of 15 genes were selected as hub genes, including WDFY2, KIT, EGR1, NSD1, DSTYK, CDK14, MDM2, RPS6KA5, CYP1A1, POLR3B, SMC5, DNAI1, SSH2, TRIM24 and CASK.

OS analysis

OS analysis was performed using R software to investigate the prognostic value of the 88 DEGs and the results were presented as Kaplan-Meier curves. Among the 37 upregulated DEGs, CASK, IL32, and KRT7 were significantly associated with prognosis. In addition, among the 51 downregulated DEGs, the expression levels of CDK14, CXCL5, CYP27C1, DNAI1, FUBP1, TRIM24 and ZMAT1 were identified to be significantly associated with prognosis (Fig. 4). Furthermore, among the downregulated DEGs, high expression levels of CXCL5, CYP27C1, FUBP1, CDK14 and TRIM24 were associated with significantly worse overall survival (Fig. 4), which suggests inhibition of the β-catenin-TCF7L1 complex may result in the downregulation of these five potential oncogenic genes. Notably, CDK14 and TRIM24 were identified as hub genes in the PPI network, which indicates these genes may be the key downstream regulators of the β-catenin-TCF7L1 complex.

Figure 4.

Overall survival analysis. Ten DEGs of the 88 DEGs were selected for overall survival analysis, including the upregulated genes CASK, IL32 and KRT7, and the downregulated genes CDK14, CXCL5, CYP27C1, DNAI1, FUBP1, TRIM24 and ZMAT1. Overall survival analysis was performed using R software. DEG, differentially expressed gene.

Promoter analysis of DEGs

Promoter analysis of DEGs performed using the Ensemble and Genomatix databases revealed that the predicted TFs of the five DEGs associated with poor OS, including CXCL5, CYP27C1, FUBP1, CDK14 and TRIM24, covered different TF families. Only TFs associated with TCF7L1 were selected to obtain a precise result. As presented in the Fig. 5, TCF7L1 was identified as a TF of four of the DEGs but not CXCL5. This result suggests that TCF7L1 may not be a TF of CXCL5, however, certain unavoidable errors of the prediction may have occurred. Furthermore, the locations of predicted TF sites of each promoter are demonstrated distinctly in Fig. 5. Two DEGs, including CDK14 and FUBP1, exhibited only one TF site, whereas, TRIM24 and CYP27C1 possessed two different sites. In addition, the locations of the two TF sites of TRIM24 were separated by <5 base pairs (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Promoter analysis of DEGs. Five DEGs including, CDK14, CYP27C1, FUBP1, CXCL5 and TRIM24 were analyzed using the Ensemble and Genomatix database to predict their interaction with the transcription factor TCF7L1, which belongs to the LEF-TCF family. The locations of the predicted TCF7L1 sites of each promoter are demonstrated with blue vertical line and numbers. +1 indicates the translation start site. Grey boxes represent exons. DEG, differentially expressed gene; TCF7L1, transcription factor 7 like 1.

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer is a highly lethal type of tumor of the digestive tract as its mortality rate is closely associated with the incidence rate (19). The majority of patients with pancreatic cancer exhibit no clinical signs until the disease reaches an advanced stage (20). Despite rapid developments in treatment strategies, effective early detective tests and drug targets for pancreatic cancer remain limited (21). Therefore, further understanding of the mechanisms underlying pancreatic cancer carcinogenesis is essential to improve prognosis and reduce the mortality rate. With developments in microarray technology, it can be useful to determine the general genetic alterations associated with disease progression, which may provide beneficial insight into the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of the disease (22).

The present study selected two datasets of pancreatic cancer in which β-catenin and TCF7L1 knockdown had been performed separately to identify DEGs. A total of 88 shared DEGs were screened out consisting of 37 upregulated and 51 downregulated DEGs. According to functional and pathway enrichment analysis, the shared DEGs were predominantly involved in transport, transcription, and the cytokine and chemokine mediated signaling pathway process. Furthermore, a PPI network was constructed and 15 genes were selected as hub genes, including WDFY2, KIT, EGR1, NSD1, DSTYK, CDK14, MDM2, RPS6KA5, CYP1A1, POLR3B, SMC5, DNAI1, SSH2, TRIM24 and CASK. According to OS analysis, high expression levels of CXCL5, CYP27C1, FUBP1, CDK14 and TRIM24, which were downregulated by inhibition of the β-catenin-TCF7L1 complex, were associated with worse prognosis. Notably, both CDK14 and TRIM24 were identified as hub genes in the PPI network and were negatively associated with OS, which suggests these two genes may serve key roles downstream of β-catenin-TCF7L1 complex.

CDK14, a member of the cyclin-dependent kinases, is a cdc2-associated serine/threonine protein kinase, which serves a vital role in normal cell cycle progression (23). It has been reported that CDK14 may interact with cyclin D3 and human cyclin Y to regulate cell cycle and cell proliferation (24,25). Furthermore, certain reports have suggested that CDK14 also regulates a number of pathways, including the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling pathway, and cellular mechanisms to act as an oncogene (26,27). It is understood that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is a conserved signaling pathway associated with cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis, differentiation and normal stem cell self-renewal (28). In the absence of Wnt signaling, the mitosis-specific CDK14-Cyclin Y kinase complex phosphorylates Ser-1490 of LRP5/6, which are co-receptors for Wnt ligands at the G2/M stage, thereby triggering the receptor for Wnt-induced phosphorylation (29,30). Furthermore, a previous study has identified that CDK14 is highly expressed in pancreatic cancer, which promotes the proliferation, migration and invasion of cancer cells (31). In addition, this high expression has been observed in a number of other types of malignant tumor, including hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric cancer and breast cancer (26,32,33). By contrast, knockout or inhibition of CDK14 has been demonstrated to exhibit a benefit on the prognosis of cancer types, including ovarian cancer and breast cancer (32,34). Furthermore, the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway also serves a vital role in cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis and differentiation, and dysregulation of this pathway is common in pancreatic cancer. A previous study demonstrated that knockdown of CDK14 inhibited the proliferation and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells, in addition to the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, by suppressing the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (31).

TRIM24, also termed transcription intermediary factor 1-α, is a member of the transcription intermediary factor family and has been confirmed to serve a key role in tumor development and progression (35,36). Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that TRIM24 is upregulated in several types of cancer and involved in numerous pathways. For example, certain studies have identified that TRIM24 is overexpressed, and promotes cancer cell growth and invasion in bladder cancer and cervical cancer, possibly via the nuclear factor-κB and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways (36,37). Similarly, it has been reported that TRIM24 can accelerate cell growth and facilitate gastric cancer progression by activation of the Akt pathway (37) and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (38). Notably, in contrast to the aforementioned studies that suggest TRIM24 is an important oncogene in tumor development, TRIM24 has been identified to suppress the progression of murine hepatocellular carcinoma (39). Therefore, the contradictory role or TRIM24 requires further investigation.

In addition to CDK14 and TRIM24, three other genes downstream of β-catenin-TCF7L1 were revealed to be negatively associated with prognosis including, CXCL5, CYP27C1 and FUBP1. CXCL5, CYP27C1 and FUBP1 were not identified as hub genes in the PPI network; however, these genes may also be target genes that affect OS and respond to the β-catenin-TCF7L1 complex.

FUBP1 encodes far upstream element-binding protein 1; a single stranded DNA-binding protein containing three domains that contribute to c-myc transcriptional regulation by binding to the far upstream element (40,41). As a member of the myc oncoprotein family, c-myc has been confirmed to be associated with oncogenesis (42,43). Therefore, it is not surprising that FUBP1 has also been revealed to be expressed in many types of malignant tissue and promote tumor proliferation and migration, and led to poor prognosis (44,45), which is consistent with the previous study. In addition, FUBP1 has been identified to function as an oncogene by regulating c-myc transcription in tumor progression (46). By contrast, the role of FUBP1 tumorigenesis may be c-myc independent, as a previous report demonstrated that knockdown of FUBP1 had no effect on the level of c-myc in hepatocellular carcinoma (44). In summary, FUBP1 may serve as a potential drug target due to its significant role in tumorigenesis. A recent study revealed that camptothecin and its analog SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan, may serve as a novel therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting FUBP1 (47). In addition, a previous study suggested that miR-16 may suppress FUBP1, both of which were associated with the trastuzumab response in ErbB-2-positive primary breast cancer (48).

CXCL5 is a member of the CXC subfamily of chemokines, which are produced locally in tissues. These chemokines function by interacting with specific G protein-coupled receptors, which are mainly expressed on leukocytes (49). It is well understood that chemokines serve a key role in infection and inflammation. Similarly, a number of reports have suggested that CXCL5 may contribute to pathogen- and autoimmune-induced inflammatory reactions, and angiogenesis by driving neutrophil recruitment (50,51). Furthermore, CXCL5 has also been confirmed to participate in cancer progression. Previous studies have demonstrated that overexpression of CXCL5 mediates neutrophil infiltration, and promotes cell proliferation and invasion in different types of tumor, including hepatocellular carcinoma and colorectal cancer, which suggests a poor prognosis (52,53). Knockdown of CXCL5 has been revealed to inhibit the proliferation and migration of human bladder cancer T24 cells (54). Furthermore, CXCL5 is associated with the PI3K/Akt/glycogen synthase kinase-3β/Snail signaling pathway (55,56) and epidermal growth factor (EGF)-EGF receptor signaling pathway (57), which have been demonstrated to serve significant roles in tumorigenesis.

CYP27C1 belongs to the cytochrome P450 superfamily of enzymes, which is understood to catalyze a number of reactions associated with drug metabolism (58). However, the number of studies regarding CYP27C1 is very limited. Certain studies have revealed that CYP27C1 can convert vitamin A1 into A2, which could be a switch for visual sensitivity (59,60). However, the other functions of this gene require further investigation.

In conclusion, the genes identified in the current study may serve as potential targets in pancreatic cancer. Furthermore, the associated functions and pathways may also provide information that can assist with the diagnosis and treatment of patients with pancreatic cancer. However, it is undeniable that there is a limitation of the present study due to the lack of experimental validation. In the future, the results predicted by bioinformatics analysis may be verified by advanced research and technology to provide benefits for the clinical outcome of patients with pancreatic cancer. In summary, the genes identified in the present study may provide potential targets for the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer, and they need to be validated prior to clinical use.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during the present study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

YHY, JZ and YZ participated in the design of this study and performed the statistical analysis. JZ collected important background information and contributed to the data acquisition. YZ carried out the study and contributed to figure preparation. YHY drafted the manuscript. MDX, JW and WL contributed to data acquisition, data analysis and statistical analysis. MYW and DML made great contributions to the original conception of the study and perfomed part of the data analysis. In addition, MYW and DML also performed manuscript review and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oberstein PE, Olive KP. Pancreatic cancer: Why is it so hard to treat? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6:321–337. doi: 10.1177/1756283X13478680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long J, Luo GP, Xiao ZW, Liu ZQ, Guo M, Liu L, Liu C, Xu J, Gao YT, Zheng Y, et al. Cancer statistics: Current diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer in Shanghai, China. Cancer Lett. 2014;346:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Provenzano PP, Cuevas C, Chang AE, Goel VK, Von Hoff DD, Hingorani SR. Enzymatic targeting of the stroma ablates physical barriers to treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:418–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolfgang CL, Herman JM, Laheru DA, Klein AP, Erdek MA, Fishman EK, Hruban RH. Recent progress in pancreatic cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:318–348. doi: 10.3322/caac.21190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stathis A, Moore MJ. Advanced pancreatic carcinoma: Current treatment and future challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:163–172. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, Ma Q, Li P, Sha H, Li X, Xu J. Aberrant expression of CXCR4 and β-catenin in pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:4103–4110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hrckulak D, Kolar M, Strnad H, Korinek V. TCF/LEF transcription factors: An update from the internet resources. Cancers. 2016;8(pii):E70. doi: 10.3390/cancers8070070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu L, Zhi Q, Shen M, Gong FR, Zhou BP, Lian L, Shen B, Chen K, Duan W, Wu MY, et al. FH535, a β-catenin pathway inhibitor, represses pancreatic cancer xenograft growth and angiogenesis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:47145–47162. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behrens J, von Kries JP, Kühl M, Bruhn L, Wedlich D, Grosschedl R, Birchmeier W. Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature. 1996;382:638–642. doi: 10.1038/382638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shang S, Hua F, Hu ZW. The regulation of β-catenin activity and function in cancer: Therapeutic opportunities. Oncotarget. 2017;8:33972–33989. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duarte JG, Blackburn JM. Advances in the development of human protein microarrays. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017;14:627–641. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2017.1347042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato Y, Miya M, Fukunaga T, Sado T, Iwasaki W. MitoFish and MiFish pipeline: A mitochondrial genome database of fish with an analysis pipeline for environmental DNA metabarcoding. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1553–1555. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Győrffy B, Pongor L, Bottai G, Li X, Budczies J, Szabó A, Hatzis C, Pusztai L, Santarpia L. An integrative bioinformatics approach reveals coding and non-coding gene variants associated with gene expression profiles and outcome in breast cancer molecular subtypes. Br J Cancer. 2018;118:1107–1114. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0030-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arensman MD, Telesca D, Lay AR, Kershaw KM, Wu N, Donahue TR, Dawson DW. The CREB-binding protein inhibitor ICG-001 suppresses pancreatic cancer growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:2303–2314. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu MY, Liang RR, Chen K, Shen M, Tian YL, Li DM, Duan WM, Gui Q, Gong FR, Lian L, et al. FH535 inhibited metastasis and growth of pancreatic cancer cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:1651–1670. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S82718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D457–D462. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamisawa T, Wood LD, Itoi T, Takaori K. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2016;388:73–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ilic M, Ilic I. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:9694–9705. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i44.9694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohammed S, Van Buren G, II, Fisher WE. Pancreatic cancer: Advances in treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9354–9360. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.López-Casas PP, López-Fernández LA. Gene-expression profiling in pancreatic cancer. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2010;10:591–601. doi: 10.1586/erm.10.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duan C, Liu Y, Lu L, Cai R, Xue H, Mao X, Chen C, Qian R, Zhang D, Shen A. CDK14 contributes to reactive gliosis via interaction with cyclin Y in rat model of spinal cord injury. J Mol Neurosci. 2015;57:571–579. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0639-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton T, Schifrin BS. Delayed cesarean section in preeclampsia with placental abruption and fetal distress. J Perinatol. 1991;11:182–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li S, Song W, Jiang M, Zeng L, Zhu X, Chen J. Phosphorylation of cyclin Y by CDK14 induces its ubiquitination and degradation. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:1989–1996. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang L, Zhu J, Huang H, Yang Q, Cai J, Wang Q, Zhu J, Shao M, Xiao J, Cao J, et al. PFTK1 promotes gastric cancer progression by regulating proliferation, migration and invasion. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang B, Zou A, Ma L, Chen X, Wang L, Zeng X, Tan T. miR-455 inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation through targeting CDK14. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;807:138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prakash N, Wurst W. A Wnt signal regulates stem cell fate and differentiation in vivo. Neurodegener Dis. 2007;4:333–338. doi: 10.1159/000101891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davidson G, Niehrs C. Emerging links between CDK cell cycle regulators and Wnt signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X, Jia Y, Fei C, Song X, Li L. Activation/proliferation-associated protein 2 (Caprin-2) positively regulates CDK14/Cyclin Y-mediated lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 and 6 (LRP5/6) constitutive phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:26427–26434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.744607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng L, Zhou Z, He Z. Knockdown of PFTK1 inhibits tumor cell proliferation, invasion and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:14005–14012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gu X, Wang Y, Wang H, Ni Q, Zhang C, Zhu J, Huang W, Xu P, Mao G, Yang S. Upregulated PFTK1 promotes tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2015;32:195. doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0641-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du B, Zhang P, Tan Z, Xu J. MiR-1202 suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma cells migration and invasion by targeting cyclin dependent kinase 14. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;96:1246–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.11.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang W, Liu R, Tang C, Xi Q, Lu S, Chen W, Zhu L, Cheng J, Chen Y, Wang W, et al. PFTK1 regulates cell proliferation, migration and invasion in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;85:405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang LH, Yin AA, Cheng JX, Huang HY, Li XM, Zhang YQ, Han N, Zhang X. TRIM24 promotes glioma progression and enhances chemoresistance through activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Oncogene. 2015;34:600–610. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xue D, Zhang X, Zhang X, Liu J, Li N, Liu C, Liu Y, Wang P. Clinical significance and biological roles of TRIM24 in human bladder carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:6849–6855. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miao ZF, Wang ZN, Zhao TT, Xu YY, Wu JH, Liu XY, Xu H, You Y, Xu HM. TRIM24 is upregulated in human gastric cancer and promotes gastric cancer cell growth and chemoresistance. Virchows Arch. 2015;466:525–532. doi: 10.1007/s00428-015-1737-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fang Z, Deng J, Zhang L, Xiang X, Yu F, Chen J, Feng M, Xiong J. TRIM24 promotes the aggression of gastric cancer via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:1797–1806. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang S, Minter LC, Stratton SA, Yang P, Abbas HA, Akdemir ZC, Pant V, Post S, Gagea M, Lee RG, et al. TRIM24 suppresses development of spontaneous hepatic lipid accumulation and hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. J Hepatol. 2015;62:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bazar L, Harris V, Sunitha I, Hartmann D, Avigan M. A transactivator of c-myc is coordinately regulated with the proto-oncogene during cellular growth. Oncogene. 1995;10:2229–2238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J, Chen QM. Far upstream element binding protein 1: A commander of transcription, translation and beyond. Oncogene. 2013;32:2907–2916. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kozma L, Kiss I, Nagy A, Szakáll S, Ember I. Investigation of c-myc and K-ras amplification in renal clear cell adenocarcinoma. Cancer Lett. 1997;111:127–131. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(96)04527-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lian Y, Niu X, Cai H, Yang X, Ma H, Ma S, Zhang Y, Chen Y. Clinicopathological significance of c-MYC in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1–7. doi: 10.1177/1010428317715804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rabenhorst U, Beinoraviciute-Kellner R, Brezniceanu ML, Joos S, Devens F, Lichter P, Rieker RJ, Trojan J, Chung HJ, Levens DL, Zörnig M. Overexpression of the far upstream element binding protein 1 in hepatocellular carcinoma is required for tumor growth. Hepatology. 2009;50:1121–1129. doi: 10.1002/hep.23098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malz M, Weber A, Singer S, Riehmer V, Bissinger M, Riener MO, Longerich T, Soll C, Vogel A, Angel P, et al. Overexpression of far upstream element binding proteins: A mechanism regulating proliferation and migration in liver cancer cells. Hepatology. 2009;50:1130–1139. doi: 10.1002/hep.23051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang L, Zhu JY, Zhang JG, Bao BJ, Guan CQ, Yang XJ, Liu YH, Huang YJ, Ni RZ, Ji LL. Far upstream element-binding protein 1 (FUBP1) is a potential c-Myc regulator in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and its expression promotes ESCC progression. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:4115–4126. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khageh Hosseini S, Kolterer S, Steiner M, von Manstein V, Gerlach K, Trojan J, Waidmann O, Zeuzem S, Schulze JO, Hahn S, et al. Camptothecin and its analog SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan, inhibit binding of the transcriptional regulator and oncoprotein FUBP1 to its DNA target sequence FUSE. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017;146:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Venturutti L, Cordo Russo RI, Rivas MA, Mercogliano MF, Izzo F, Oakley RH, Pereyra MG, De Martino M, Proietti CJ, Yankilevich P, et al. MiR-16 mediates trastuzumab and lapatinib response in ErbB-2-positive breast and gastric cancer via its novel targets CCNJ and FUBP1. Oncogene. 2016;35:6189–6202. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Disteldorf EM, Krebs CF, Paust HJ, Turner JE, Nouailles G, Tittel A, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Stege G, Brix S, Velden J, et al. CXCL5 drives neutrophil recruitment in TH17-mediated GN. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:55–66. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013101061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mei J, Liu Y, Dai N, Hoffmann C, Hudock KM, Zhang P, Guttentag SH, Kolls JK, Oliver PM, Bushman FD, Worthen GS. Cxcr2 and Cxcl5 regulate the IL-17/G-CSF axis and neutrophil homeostasis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:974–986. doi: 10.1172/JCI60588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nouailles G, Dorhoi A, Koch M, Zerrahn J, Weiner J, III, Faé KC, Arrey F, Kuhlmann S, Bandermann S, Loewe D, et al. CXCL5-secreting pulmonary epithelial cells drive destructive neutrophilic inflammation in tuberculosis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1268–1282. doi: 10.1172/JCI72030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou SL, Dai Z, Zhou ZJ, Wang XY, Yang GH, Wang Z, Huang XW, Fan J, Zhou J. Overexpression of CXCL5 mediates neutrophil infiltration and indicates poor prognosis for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2012;56:2242–2254. doi: 10.1002/hep.25907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Speetjens FM, Kuppen PJ, Sandel MH, Menon AG, Burg D, van de Velde CJ, Tollenaar RA, de Bont HJ, Nagelkerke JF. Disrupted expression of CXCL5 in colorectal cancer is associated with rapid tumor formation in rats and poor prognosis in patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2276–2284. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zheng J, Zhu X, Zhang J. CXCL5 knockdown expression inhibits human bladder cancer T24 cells proliferation and migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;446:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao J, Ou B, Han D, Wang P, Zong Y, Zhu C, Liu D, Zheng M, Sun J, Feng H, Lu A. Tumor-derived CXCL5 promotes human colorectal cancer metastasis through activation of the ERK/Elk-1/Snail and AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin pathways. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:70. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0629-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou SL, Zhou ZJ, Hu ZQ, Li X, Huang XW, Wang Z, Fan J, Dai Z, Zhou J. CXCR2/CXCL5 axis contributes to epithelial-mesenchymal transition of HCC cells through activating PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β/Snail signaling. Cancer Lett. 2015;358:124–135. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang P, Xu X, Wang L, Zhu B, Wang X, Xia J. The role of EGF-EGFR signalling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma inflammatory microenvironment. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18:218–230. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson KM, Phan TTN, Albertolle ME, Guengerich FP. Human mitochondrial cytochrome P450 27C1 is localized in skin and preferentially desaturates trans-retinol to 3,4-dehydroretinol. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:13672–13687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.773937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Enright JM, Toomey MB, Sato SY, Temple SE, Allen JR, Fujiwara R, Kramlinger VM, Nagy LD, Johnson KM, Xiao Y, et al. Cyp27c1 red-shifts the spectral sensitivity of photoreceptors by converting vitamin A1 into A2. Curr Biol. 2015;25:3048–3057. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morshedian A, Toomey MB, Pollock GE, Frederiksen R, Enright JM, McCormick SD, Cornwall MC, Fain GL, Corbo JC. Cambrian origin of the CYP27C1-mediated vitamin A1-to-A2 switch, a key mechanism of vertebrate sensory plasticity. R Soc Open Sci. 2017;4:170362. doi: 10.1098/rsos.170362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: The 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during the present study are included in this published article.