Abstract

Base-pair opening is a conformational transition that is required for proper biological function of nucleic acids. Hydrogen exchange, observed by NMR spectroscopic experiments, is a widely used method to study the thermodynamics and kinetics of base-pair opening in nucleic acids. The hydrogen exchange data of imino protons are analyzed based on a two-state (open/closed) model for the base-pair, where hydrogen exchange only occurs from the open state. In this review, we discuss examples of how hydrogen exchange data provide insight into several interesting biological processes involving functional interactions of nucleic acids: i) selective recognition of DNA by proteins; ii) regulation of RNA cleavage by site-specific mutations; iii) intermolecular interaction of proteins with their target DNA or RNA; iv) formation of PNA:DNA hybrid duplexes.

Keywords: NMR, Nucleic acids, Base-pair opening, Hydrogen exchange, DNA, RNA

Highlights

-

•

This review systematically summarizes hydrogen exchange theory for base-paired imino protons of nucleic acids.

-

•

Base-pair opening kinetics explain how the DNA can be selectively recognized by its target proteins.

-

•

Base-pair opening kinetics explain the mechanisms by which site-specific mutations regulate RNA cleavage.

-

•

Hydrogen exchange studies can elucidate the intermolecular interaction of proteins with their target DNA or RNA.

1. Introduction

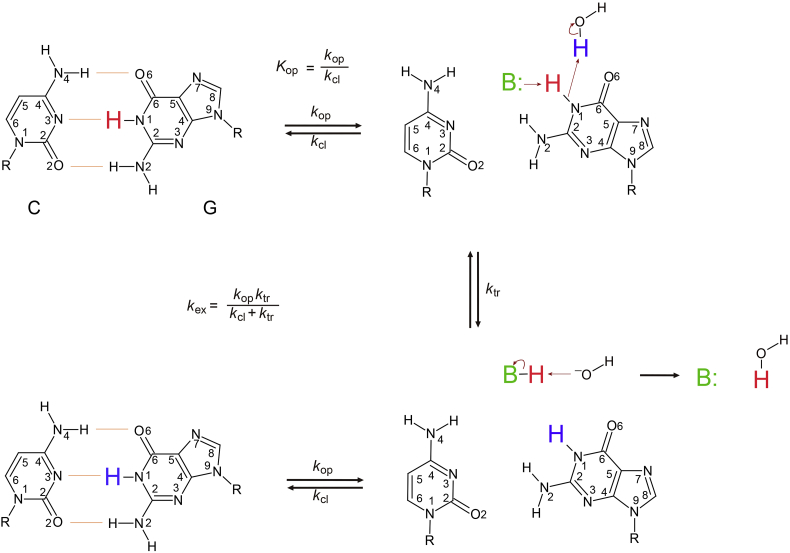

Base-pair opening in DNA is a structural fluctuation that is required for its biological function in transcription, repair, and recombination. RNA also undergoes conformational transitions that exhibit distinct structural and dynamic features required for proper function. The hydrogen-bonded imino protons of nucleic acids are a probe of the base-pair opening kinetics. Hydrogen exchange NMR experiments provide information on the thermodynamics and kinetics of base-pair opening and therefore represent a probe of the dynamic motions of the base-pairs. Analysis of the hydrogen exchange of imino protons employs a two-state (open/closed) model for the base-pair, where hydrogen exchange only occurs from the open state (Fig. 1) [[1], [2], [3]]. The opening (kop) and closing (kcl) rate constants and/or equilibrium constant for base-pair opening (Kop = kop/kcl) can be determined by measuring the exchange using an external catalyst. These experiments have been used to probe base-pair opening in various DNA duplexes [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]], DNAs containing modified base such as 5-flurourasil, N6-methyl adenine, or modified guanine [[19], [20], [21]], UV-induced photoadduct-containing DNA [22], IHF-complexed DNA [23], interstrand cross-linked DNA [24], i-motif structure formed by the complementary C-rich DNA [25,26], various RNAs [15,[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36]], peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) [37,38], and threose nucleic acid (TNA) [39]. NMR exchange and single molecule FRET experiments could be used to study the protonation/deprotonation of adenine bases and formation of A+·C wobble pair [[40], [41], [42], [43], [44]]. In addition, hydrogen exchange data can also be used to probe how intermolecular interactions stabilize nucleic acid duplexes. For example, imino proton exchange studies of a DNA/RNA-protein complex by NMR spectroscopy showed that the protein substantially changes the equilibrium constant for base-pair opening [[45], [46], [47], [48], [49]].

Fig. 1.

Two-state (open/closed) model for the base-pair, where hydrogen exchange of the imino proton only occurs from the open state by the base catalyst (B:).

In this review, we discuss several examples of how hydrogen exchange data provide insight into the biological function of interesting nucleic acids. Studies of base-pair opening kinetics have been used to propose mechanisms by which DNA is selectively recognized by its target proteins. Selective recognition is used by seqA to distinguish the hemimethylated GATC from the corresponding fully methylated complex [20], and the higher binding affinity of XPC-hHR23B for a double mismatched cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD) helps it distinguish the double mismatch from the matched or single mismatched CPD species [22]. Base-pair opening kinetics studies can also suggest the mechanisms that explain how RNA cleavage can be regulated by site-specific mutations, e.g., in the case of the biogenesis of miRNA156a by DICER-like 1 protein (DCL1) [31] and self-cleavage of the Tetrahymena group I ribozyme [28]. Hydrogen exchange studies can elucidate the intermolecular interactions of proteins with their target DNA or RNA, as in the case of B-Z transition of DNA [50] and B-Z junction formation [49] facilitated by Z-DNA binding proteins (ZBPs), and VEGF-targeting of RNA aptamers [51]. Finally, we also describe recent hydrogen exchange studies of a PNA:DNA hybrid duplex [38].

2. Hydrogen Exchange Theory

2.1. Hydrogen Exchange of the Base-Paired Imino Protons

Imino proton exchange from a base-pair consists of a two-step process requiring base-pair opening followed by proton transfer to a base catalyst (Fig. 1). The rate constant for imino proton exchange (kex) is given by Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where kop and kcl are the rate constants for opening and closing of the base-pair, respectively, and ktr is the rate constant for proton exchange by base catalyst in the opening state. In the base-pair, the exchange is catalyzed by both the added base catalyst and the nitrogen of the complementary base, which acts as an intrinsic catalyst [1,2]. The ktr value is calculated as:

| (2) |

where kB is the rate constant for imino proton transfer by a base catalyst, kint is the exchange rate constant catalyzed by an intrinsic base, kcoll is the collision rate constant, [B] is the concentration of the externally added base catalyst such as ammonia, Tris, phosphate, and difluoroethylamine (base form) and ΔpKa is the pKa difference between the imino proton and the base catalyst. The [B] values are calculated as [B] = [B]total/(1 + 10(pKa–pH)), where [B]total is the total concentration of the added base catalyst [28,38]. Thus, the kex for the base-paired imino proton is represented by Eq. (3):

| (3) |

where Kop (= kop/kcl) is the equilibrium constant for base-pair opening. Re-organization of Eq. (3) yields the following equation:

| (4) |

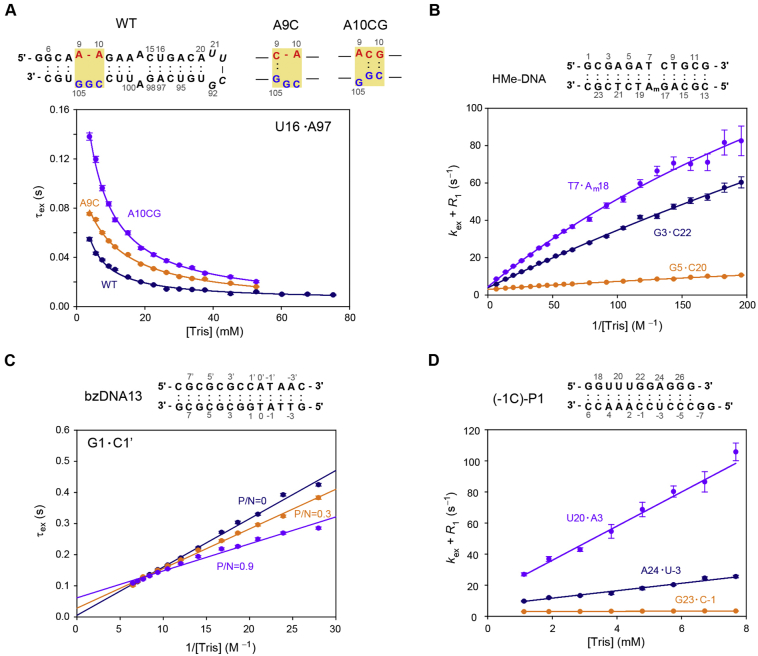

where τex is the exchange time (= 1/kex) and τ0 is the lifetime for closed state of the base-pair (= 1/kop). Interestingly, curve fitting the τex of the imino protons as a function of the concentration (base form) of the added base catalyst ([B]) within Eq. (4) gives not only the thermodynamic parameter, Kop, but also kinetic parameter, τ0 (= 1/kop) value (Fig. 2A) [31,32]. As [B] increases, the τex values converge to the base-pair lifetime, τ0, in these plots. For example, the U16·A97 base-pair in the wild-type (WT) primary miRNA156a model RNA is expected to have a longer τ0 than that of the A9C and A10CG mutants (τ0 of WT, 5.0 ms; A9C, 1.0 ms; A10CG, 1.6 ms) (Fig. 2A) [31]. The lifetime for open state of the base-pair (τopen = 1/kcl) is calculated using the relation τopen = Kop × τ0.

Fig. 2.

Hydrogen exchange data of the (A) primary miRNA156a modeled RNA (pri-miR156a) [33], (B) DNA dodecamer duplex containing hemimethylated GATC site (HMe-GATC) [20], (C) DNA 13mer duplex (bzDNA13) complexed with ZαADAR1 [39], and (D) (-1C)-mutant P1 RNA duplex ((-1C)-P1) [30]. The solid lines are the best fits to Eqs. (4), (5), (6), (7), respectively, and the error bars represent the fitting errors during determination of R1a (= R1 + kex) or τex (= 1/kex) values. [Tris] is the concentration of Tris (base form) which is used for the base catalyst. Secondary structures of the wild-type (WT) and A9C and A10CG mutant pri-miR156a (in (A)), HMe-GATC (in (B)), bzDNA13 (in (C)), and (-1C)-P1 (in (D)) are shown on top of each hydrogen exchange data.

Under certain conditions where kB[B] is much larger than kint, Eq. (3) simplifies to Eq. (5):

| (5) |

In this case, parameters for the base-pair opening dynamics can be determined by curve fitting the exchange data using Eq. (5) (Fig. 2B) [20,21]. The apparent relaxation rate constant (R1a) for an imino proton determined by NMR experiments is the sum of the kex value and the R1 relaxation rate constant. As [B] increased, the kex values converge to the kop value in these plots. For example, in duplex DNA containing a hemimethylated GATC site, the T7·A18 and G3·C22 base-pairs are expected to have larger kop (that is, shorter τ0) than the G5·C20 base-pair (τ0 of T7·A18, 2.4 ms; G3·C22, 2.0 ms; G5·C20, 24.4 ms) (Fig. 2B) [20]. Similarly, under these conditions (kB[B] > > kint), Eq. (4) becomes:

| (6) |

Curve fitting the τex as a function of the inverse of [B] (1/[B]) with Eq. (6) gives the Kop and τ0 values (Fig. 2C) [38,49]. The slope of the linear correlation between τex and 1/[B] is τ0 and the y-intercept is 1/(kBKop). Thus, the imino proton of a more slowly opened base-pair with longer τ0 has a larger y-intercept, while that of a less stable base-pair with larger Kop has a smaller slope in these plots. For example, in the DNA duplexes complexed with the Zα domain of human double-stranded RNA deaminase I, ADAR1, (ZαADAR1), the G1·C1′ base-pair is expected to have a longer τ0 (P/N = 0, <1 ms; P/N = 0.3, 29 ms; P/N = 0.9, 106 ms) and a larger Kop (P/N = 0, 0.76 × 10−6; P/N = 0.3, 0.95 × 10−6; P/N = 0.9, 1.31 × 10−6), as the protein/DNA (P/N) molar ratio increases (Fig. 2C) [49].

In addition, if kcl (= kop/Kop) is much larger than kB[B], Eq. (5) simplifies to:

| (7) |

In this case, the Kop values can be determined from the slope of the linear correlation between the kex and [B] (Fig. 2D) [28]. The imino proton of a less stable base-pair with larger Kop has a larger slope in these plots. For example, in the (-1C)-mutant P1 duplex of Tetrahymena ribozyme, the U20·A3 base-pair is expected to be less stable with a larger Kop than the A24·U-3 and G23·C-2 base-pairs (Kop of U20·A3, 83 × 10−6; A24·U-3, 21 × 10−6; G23·C-2, <1.5 × 10−6) (Fig. 2D) [28].

The Gibbs free energy difference (ΔGobp) between the closed and open states is calculated from the equilibrium constant for base-pair opening using Eq. (8):

| (8) |

where ΔGoopening is the Gibbs free energy change in the opening process, T is the absolute temperature and R is the universal gas constant [20,21,31]. The activation energies for base-pair opening (ΔG‡op) and closing (ΔG‡cl) are related to the kop and kcl values, respectively, by the Arrhenius equation. The differences in ΔGobp and activation energies for base-pair opening (ΔΔG‡op) and closing (ΔΔG‡cl) in wild-type and modified nucleic acids are calculated using Eqs. (9), (10), (11), respectively:

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

where the subscripts, wt and mod, indicate the thermodynamic parameters of the wild-type and modified nucleic acids, respectively [20,31].

2.2. NMR Measurement of Hydrogen Exchange Rates

The hydrogen exchange rates of the imino protons were determined by a water magnetization transfer experiment, where a selective 180° pulse for water was applied, followed by a variable delay (t), and then a Watergate acquisition pulse was used to suppress the water signal [27,28,52]. During the delay times between selective water inversion and acquisition pulses, a weak gradient (0.02 G/cm) was applied to prevent the radiation damping of the water signal [27,28]. The exchange rate constants (kex) were determined by fitting the relative peak intensities, I(t)/I0, of the imino protons to:

| (12) |

where I(t) and I0 are the peak intensities of the imino proton at delay times t and zero, respectively, R1a and R1w are the apparent relaxation rate constants for the imino protons and water, respectively, which were determined by inversion recovery experiments [28].

The water magnetization transfer method is prone to some artifacts such as exchange-relayed NOE from rapidly exchanging protons in nucleic acids [53]. To suppress efficiently this artifact, a phase-modulated CLEAN chemical exchange spectroscopy (CLEANEX-PM) was applied to the mixing period of a water-selective pulse sequence [53]. The hydrogen exchange data for various nucleic acids using CLEANEX-PM have been reported [[53], [54], [55], [56]].

Generally, the imino protons in double-helical regions have relatively fast exchange kinetics (kex = 0.1–100 s−1 at 25 °C). Interestingly, very slowly exchanging imino protons have been observed for modified tRNAs [[57], [58], [59]]. Hydrogen-deuterium exchange experiments were used to probe the dynamics and flexibility of the slowly exchanging imino protons in various nucleic acid systems [[57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62]].

3. Implications for Specific DNA Recognition

3.1. Recognition of Hemimethylated GATC Site

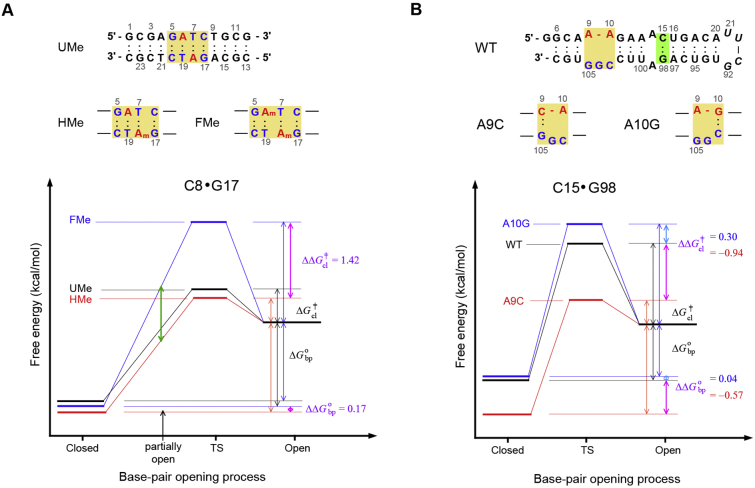

Many DNA binding proteins recognize their particular DNA sequences in a highly selective manner. The DNA-protein interactions require sequence-specific hydrogen bonding, van der Waals interactions, sequence-dependent structural changes. In addition, the flexibility of a DNA duplex to adopt the unique structure in complex is important in sequence-specific recognition. Enzymatic methylation of DNA occurs abundantly in most living organisms and regulates a variety of cellular processes. Escherichia coli (E. coli) DNA adenine methyltransferase (dam) methylates the N6 of adenines, to form the N6-methylated A (m6A), within 5’-GATC-3′ sites at the replication origin oriC [63]. The E. coli seqA protein prefers to bind to newly synthesized, hemimethylated, rather than fully methylated, GATC sites to inhibit the initiation of the second round of chromosomal replication [64]. It was reported that the m6A modification destabilizes the base-pairing of RNA duplexes, because the m6A exhibited high energy anti conformation to maintain the Watson-Crick m6A·T base-pair [[65], [66], [67]]. However, in the GATC-containing DNA duplexes, the m6A methylation at the GATC site stabilized the base-pairs at the GATC site [20]. The crystal structure of the seqA protein complexed with a hemimethylated GATC sequence revealed that the two G·C base-pairs exhibited longer heavy atom distances between G-O6 and C-N4 than that of a Watson-Crick base-pair (see Fig. 1), indicating the a partially opened G·C base-pair [68]. However, in the solution structure of the DNA duplex containing hemimethylated GATC, these two base-pairs formed the stable Watson-Crick base-pairs [69]. Interestingly, NMR hydrogen exchange studies revealed that the ΔΔG‡cl value, calculated using Eq. (11), of the 3′-neighboring G·C base-pair of the N6-methylated adenine between the DNA duplexes containing the hemimthylated and fully methylated GATC sites is 1.42 kcal/mol, although the ΔΔGobp value, calculated using Eq. (9), is only 0.17 kcal/mol (Fig. 3A) [20]. Using free energy differences calculated from these hydrogen exchange data as shown in Fig. 3A, it was shown that the partial opening of the G·C base pairs in the hemimethylated GATC sequence required a much smaller amount of energy than fully methylated GATC (Fig. 3A) [20]. Thus, it was concluded that the hemimethylated GATC site is energetically more favorable for complex formation with seqA than the corresponding fully methylated complex [20].

Fig. 3.

Schematic representations of the Gibbs free energy diagram of the base-pair opening and closing for (A) the G·C base-pair adjacent to the N6-methylated adenine (Am) residue in DNA duplexes containing unmethylated (UMe, black), hemimethylated (HMe, red), or fully methylated (FMe, blue) GATC sites [20] and (B) the C15·G98 base-pair in the WT (black), A9C (red) and A10G (blue) primary miRNA156a [33]. Secondary structures of the UMe-, HMe-, and FMe-GATC DNA in (A) and the WT, A9C, and A10G pri-miR156a in (B) are shown on top of each figure.

3.2. Recognition of Cyclobutane Pyrimidine Dimer

The CPD is one of the major types of cytotoxic, mutagenic and carcinogenic UV-induced DNA photoproducts [70,71]. In mammalian cells, CPD-damaged DNA is repaired by nucleotide excision repair [71,72], which is initiated by the binding of XPC-hHR23B to the site of DNA damage [73,74]. Although the CPD lesions are recognized poorly by XPC-hHR23B, when CPD lesions have double T·G mismatches, the binding affinity of XPC-hHR23B is dramatically increased [74]. A structural study of CPD-containing DNA duplexes suggested that, during nucleotide excision repair, the XPC-hHR23B complex recognizes DNA damage by directly searching for conformational distortions, such as a flexible backbone, a bent helix, or an unusual groove width [75]. NMR hydrogen exchange studies found that the two thymine bases of a CPD formed stable Watson-Crick base-pairs with the two opposite adenine bases, evident by a ΔΔGobp ~ 0.2 kcal/mol relative to normal Watson-Crick T·A base-pairs [21]. When the CPD forms double T·G base-pairs, the ΔΔGobp values are >1.9 kcal/mol [21]. Interestingly, these base-pair instabilities extended to the two base-pair neighbors, which had ΔΔGobp values >1.4 kcal/mol [21]. Thus, this study concluded that a double mismatch at the CPD lesion facilitates the opening of the six base-pairs including the CPD, forming a small bubble structure that can be easily recognized by XPC-hHR23B [21].

4. Implications for Sequence-Specific RNA Cleavage

4.1. Biogenesis of miRNA156a

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs that negatively regulate expression of their target genes [76]. In plants, primary miRNAs are sequentially cleaved by DCL1 to make mature miRNA. MiRNA156 plays an important role in the temperature-responsive flowering of plants [77,78]. Plants overexpressing miRNA156 produced more leaves than wild-type plants before flowering by regulating the expression of the SQUAMOSA promoter binding protein-like (SPL) gene family [79,80]. The point mutations which stabilize the B5 bulge of primary miRNA156a affected the mature 156 levels as well as the leaf numbers at flowering of miRNA156 overexpressing plants [31,32]. NMR hydrogen exchange studies revealed that the C·G and U·A base-pairs at the DCL1 cleavage site exhibited unique base-pair stability and opening dynamics, which correlated with the biogenesis of miRNA156a [31,32]. For example, the C15·G98 base-pair in the A9C mutant, which decreased mature miRNA156 levels but decreased the leaf number at flowering compared to wild-type primary miRNA156a, was more stable with a ΔΔGobp of −0.57 kcal/mol, and showed more dynamic opening/closing, with a ΔΔG‡cl of −0.94 kcal/mol (Fig. 3B) [31]. Similar results were observed for the U16·A97 base-pair [31]. However, the A10G mutant, in which the C15·G98 base-pair had a ΔΔGobp of 0.04 kcal/mol and a ΔΔG‡cl of 0.30 kcal/mol (Fig. 3B), did not affect the mature miRNA156 levels or the flowering time of the plants [31]. Thus, it was concluded that precisely tuned base-pair stability/flexibility at the DCL1 cleavage site is essential for efficient processing of primary miRNA156 and can be modulated by mutations adjacent to the cleavage site [31].

4.2. Self-Cleavage of the P1 Duplex of the Tetrahymena Group I Ribozyme

The Tetrahymena L-21 ScaI ribozyme is derived from the self-splicing group I intron and catalyzes a transesterification reaction in the P1 duplex formed with the internal guide sequence in the ribozyme and substrate RNA [81]. Various modifications of the P1 duplex have been shown to affect the cleavage reaction and kinetics for docking of the P1 duplex into the catalytic core [82,83]. NMR hydrogen exchange studies showed that the conserved U-1·G22 wobble pair, which is required for activity of the ribozyme (the cleavage site is the phosphodiester bond between A2 and U-1), destabilizes the neighboring A2·U21 base-pair, whereas the other neighboring C-2·G23 base-pair is the most stable base-pair in the P1duplex [28]. For efficient cleavage of substrate RNA, this P1 duplex docks into the catalytic core of the ribozyme and forms the active conformation [84,85]. In the active conformation, the G22 forms a tertiary interaction with adenine in the catalytic core and then the U-1·G22 wobble pair becomes destabilized [84,85]. Replacing the conserved U-1·G22 wobble pair with a Watson-Crick C·G base-pair leads to 200- and 9-fold smaller Kop values for this and the A2·U21 base-pairs, respectively, at the cleavage site [28]. This stabilization of the cleavage site explains the 80-fold increase of the undocking rate with the mutant sequence [83].

5. Implications for DNA/RNA-Protein Interactions

5.1. B-Z Transition of DNA by Z-DNA Binding Proteins

ZBPs play important roles in RNA editing, innate immune response and viral infection [[86], [87], [88]]. The crystal structures of ZBPs in complex with a 6-base-pair DNA duplex revealed that two molecules of ZBPs bind to each strand of double-stranded Z-DNA, yielding 2-fold symmetry with respect to the DNA helical axis [[89], [90], [91], [92]]. ADAR1 deaminates adenine in pre-mRNA to yield inosine [89]. ADAR1 has two ZBPs, Zα and Zβ, at its NH2-terminus [89]. Hydrogen exchange measurements on the duplex DNA complexed with Zα domain of human ADAR1 (ZαADAR1) revealed that the kex of the G imino protons in the left-handed Z-form helix decreased from 11.1 to 4.8 s−1 as the protein-to-DNA (P/N) molar ratio increased from 0.7 to 2.5 [50]. This observation indicates the possible presence of a mixture of two complex state: DNA-ZαADAR1 and DNA-(ZαADAR1)2 [50]. These results support an active B-Z transition mechanism in which the ZαADAR1 protein first binds to B-DNA and then converts it to left-handed Z-DNA, a conformation that is then stabilized by the additional binding of a second ZαADAR1 molecule [50]. Similar hydrogen exchange studies were performed for DNA duplexes complexed with other ZBPs [[93], [94], [95], [96]].

5.2. B-Z Junction Formation in DNA by Z-DNA Binding Proteins

In order for ZBPs to produce Z-DNA in a section of long genomic DNA, two B-Z junctions must be formed at each end of the Z-DNA segment. A crystal structural study of a DNA duplex complexed with ZαADAR1 showed that bases between B- and Z-DNA are almost continuously stacked, with the extrusion of one base-pair at the B-Z junction [97]. Hydrogen exchange studies of the DNA-ZαADAR1 complexes showed that the kex values of the A·T base-pairs in AT-rich regions increased as the P/N ratio increased, indicating that ZαADAR1 significantly destabilizes AT-rich regions [49,98]. However, ZαADAR1 had little effect on the kex values of the G·C base-pairs in CG-rich regions [49,98]. In addition, the base-pair opening kinetics indicated that, in the complex, all G·C base-pairs have larger Kop values (smaller slopes in Fig. 2C) and longer τ0 values (larger y-intercepts in Fig. 2C) than those of free DNA [49]. Thus, it was proposed that an intermediate structure exists during B-Z junction formation by ZαADAR1, in which the DNA duplex displays unique dynamic features: (i) instability of the AT-rich region and (ii) a longer lifetime for the open state of the CG-rich region [49].

5.3. Target Recognition of RNA Aptamer

Macugen is the first modified RNA aptamer to be employed as a human therapeutic and was derived from an in vitro selection against the key angiogenic regulator protein, vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF165 [99]. VEGF consists of two independent domains, a receptor-binding domain and a 55-amino acid heparin-binding domain (HBD) [100]. A photo-crosslinking study indicated that Macugen specifically recognizes VEGF by targeting the HBD [101]. NMR studies showed very similar secondary structure for Macugen, whether it is bound to the HBD or to VEGF165 [102]. These studies also found that the aptamer is stabilized by complex formation with either the HBD or VEGF165 [102]. Hydrogen exchange studies showed that many imino protons in the internal loop and neighboring base-pairs exhibit fast exchange in the free aptamer with very large kex values [51]. However, the kex values for many of these imino protons became much smaller upon binding of the HBD or VEGF165 [51]. These hydrogen exchange data support an induced-fit type mechanism in which RNAs with dynamic features in the free state can bind their target protein with extremely high affinity [51].

6. Implications for DNA-PNA Hybrid Duplex Formation

PNAs are one of the most widely used synthetic DNA mimics where the four bases are attached to a N-(2-aminoethyl)glycine (aeg) backbone [103,104]. Chimeric PNA (chiPNA), in which a chiral glycerol nucleic acid-like γ3T monomer is incorporated into the aegPNA backbone, displays excellent RNA selectivity as well as antiparallel selectivity toward non-chimeric PNA [105]. Hydrogen exchange studies revealed that a aegPNA:DNA hybrid is a much more stable duplex (smaller Kop) and is less dynamic compared to the corresponding DNA duplex (longer τ0 and τopen) [38]. The γ3T residue in the chiPNA:DNA hybrid destabilizes a specific base-pair (much larger kex) and its neighbors (3- to 60-fold larger Kop) compared to the non-chimeric PNA:DNA hybrid, while maintaining the thermal stabilities and dynamic properties of other base pairs [38]. In addition, the two neighboring base-pairs becomes more dynamic than in either the non-chimeric PNA:DNA hybrid or the corresponding DNA duplex (much shorter τ0 and τopen), meaning that these base-pairs open and reclose much more rapidly [38].

7. Conclusion

Base-pair opening in nucleic acids is a conformational transition that is required for their biological function. Hydrogen exchange is one of the widely used methods to study the thermodynamics and kinetics of base-pair opening in nucleic acids. The hydrogen exchange data of imino protons are analyzed based on a two-state (open/closed) model, where exchange only occurs from the open state. In this review, we discussed several examples of how hydrogen exchange data provide insight into the functional interactions of nucleic acids: 1) selective recognition of DNA by its target proteins; 2) regulation of RNA cleavage by site-specific mutations; 3) intermolecular interaction of proteins with their target DNA or RNA; 4) formation of PNA:DNA hybrid duplexes.

Declarations of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea [2017R1A2B2A001832], the Samsung Science and Technology Foundation [SSRF-BA1701-10], and the KBSI grant [D39700]. We thank M. Stauffer, of Scientific Editing Solutions, for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was dedicated to Professor Byong-Seok Choi on the occasion of his retirement and 65th birthday.

References

- 1.Leroy J.L., Bolo N., Figueroa N., Plateau P., Guéron M. Internal motions of transfer RNA: a study of exchanging protons by magnetic resonance. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 1985;2:915–939. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1985.10507609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guéron M., Leroy J.L. Studies of base pair kinetics by NMR measurement of proton exchange. Methods Enzymol. 1995;261:383–413. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(95)61018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leijon M., Leroy J.L. Internal motions of nucleic acid structures and the determination of base-pair lifetimes. Biochimie. 1997;79:775–779. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(97)86936-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moe J.G., Russu I.M. Proton exchange and base-pair opening kinetics in 5′-d(CGCGAATTCGCG)-3′ and related dodecamers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:817–821. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leijon M., Gräslund A. Effects of sequence and length on imino proton exchange and base pair opening kinetics in DNA oligonucleotide duplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5339–5343. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.20.5339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moe J.G., Russu I.M. Kinetics and energetics of base-pair opening in 5′-d(CGCGAATTCGCG)-3′ and a substituted dodecamer containing G·T mismatches. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8421–8428. doi: 10.1021/bi00151a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leijon M., Zdunek J., Fritzsche H., Sklenar H., Gräslund A. NMR studies and restrained-molecular-dynamics calculations of a long a+T-rich stretch in DNA. Effects of phosphate charge and solvent approximations. Eur J Biochem. 1995;234:832–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.832_a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folta-Stogniew E., Russu I.M. Base-catalysis of imino proton exchange in DNA: effects of catalyst upon DNA structure and dynamics. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8439–8449. doi: 10.1021/bi952932z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nonin S., Jiang F., Patel D.J. Imino proton exchange and base pair kinetics in the AMP-RNA aptamer complex. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:359–374. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dornberger U., Leijon M., Fritzsche H. High base pair opening rates in tracts of GC base pairs. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6957–6962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.6957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wärmländer S., Sen A., Leijon M. Imino proton exchange in DNA catalyzed by ammonia and trimethylamine: evidence for a secondary long-lived open state of the base pair. Biochemistry. 2000;39:607–615. doi: 10.1021/bi991863b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snoussi K., Leroy J.L. Alteration of a·T base-pair opening kinetics by the ammonium cation in DNA A-tracts. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12467–12474. doi: 10.1021/bi020184p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhattacharya P.K., Cha J., Barton J.K. 1H NMR determination of base-pair lifetimes in oligonucleotides containing single base mismatches. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4740–4750. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wärmländer S., Sandström K., Leijon M., Gräslund A. Base-pair dynamics in an antiparallel DNA triplex measured by catalyzed imino proton exchange monitored via 1H NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12589–12595. doi: 10.1021/bi034479u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Várnai P., Canalia M., Leroy J.L. Opening mechanism of G·T/U pairs in DNA and RNA duplexes: a combined study of imino proton exchange and molecular dynamics simulation. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14659–14667. doi: 10.1021/ja0470721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coman D., Russu I.M. A nuclear magnetic resonance investigation of the energetics of basepair opening pathways in DNA. Biophys J. 2005;89:3285–3292. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.065763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Every A.E., Russu I.M. Influence of magnesium ions on spontaneous opening of DNA base pairs. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:7689–7695. doi: 10.1021/jp8005876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho S.J., Bang J., Lee J.H., Choi B.S. Base pair opening kinetics and dynamics in the DNA duplexes that specifically recognized by very short patch repair protein (Vsr) Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;501:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker J.B., Stivers J.T. Dynamics of uracil and 5-fluorouracil in DNA. Biochemistry. 2011;50:612–617. doi: 10.1021/bi101536k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bang J., Bae S.H., Park C.J., Lee J.H., Choi B.S. Structural and dynamics study of DNA dodecamer duplexes that contain un-, hemi- or fully-methylated GATC sites. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17688–17696. doi: 10.1021/ja8038272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szulik M.W., Voehler M.W., Ganguly M., Gold B., Stone M.P. Site-specific stabilization of DNA by a tethered major groove amine, 7-aminomethyl-7-deaza-2′-deoxyguanosine. Biochemistry. 2013;52:7659–7668. doi: 10.1021/bi400695r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bang J., Kang Y.M., Park C.J., Lee J.H., Choi B.S. Thermodynamics and kinetics for base pair opening in the decamer DNA duplexes containing cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2037–2041. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dhavan G.M., Lapham J., Yang S., Crothers D.M. Decreased imino proton exchange and base-pair opening in the IHF-DNA complex measured by NMR. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:659–671. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman J.I., Jiang Y.L., Stivers J.T. Unique dynamic properties of DNA duplexes containing interstrand cross-links. Biochemistry. 2011;50:882–890. doi: 10.1021/bi101813h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esmaili N., Leroy J.L. I-motif solution structure and dynamics of the d(AACCCC) and d(CCCCAA) tetrahymena telomeric repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:213–224. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canalia M., Leroy J.L. Structure, internal motions and association-dissociation kinetics of the i-motif dimer of d(5mCCTCACTCC) Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5471–5481. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snoussi K., Leroy J.L. Imino proton exchange and base-pair kinetics in RNA duplexes. Biochemistry. 2001;40:8898–8904. doi: 10.1021/bi010385d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J.H., Pardi A. Thermodynamics and kinetics for base pair opening in the P1 duplex of Tetrahymena group I ribozyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2965–2974. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hao Z.X., Tan M., Liu C.D., Feng R., Wang E.D., Zhu G. Studying base pair open-close kinetics of tRNALeu by TROSY-based proton exchange NMR spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:4449–4452. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen C., Jiang L., Michalczyk R., Russu I.M. Structural energetics and base-pair opening dynamics in sarcin-ricin domain RNA. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13606–13613. doi: 10.1021/bi060908n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim W., Kim H.E., Lee A.R., Jun A.R., Jung M.G., Ahn J.H. Base-pair opening dynamics of primary miR156a using NMR elucidates structural determinants important for its processing level and leaf number phenotype in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:875–885. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim H.E., Kim W., Lee A.R., Jin S., Jun A.R., Kim N.K. Base-pair opening dynamics of the microRNA precursor pri-miR156a affect temperature-responsive flowering in Arabidopsis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;484:839–844. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.01.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rinnenthal J., Klinkert B., Narberhaus F., Schwalbe H. Direct observation of the temperature-induced melting process of the Salmonella fourU RNA thermometer at base-pair resolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:3834–3847. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagner D., Rinnenthal J., Narberhaus F., Schwalbe H. Mechanistic insights into temperature-dependent regulation of the simple cyanobacterial hsp17 RNA thermometer at base-pair resolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:5572–5585. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mirau P.A., Kearns D.R. Effect of environment, conformation, sequence and base substituents on the imino proton exchange rates in guanine and inosine-containing DNA, RNA, and DNA-RNA duplexes. J Mol Biol. 1984;177:207–227. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90453-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steinert H.S., Rinnenthal J., Schwalbe H. Individual basepair stability of DNA and RNA studied by NMR-detected solvent exchange. Biophys J. 2012;102:2564–2574. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.03.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leijon M., Sehlstedt U., Nielsen P.E., Gräslund A. Unique base-pair breathing dynamics in PNA-DNA hybrids. J Mol Biol. 1997;271:438–455. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seo Y.J., Lim J., Lee E.H., Ok T., Yoon J., Lee J.H. Base-pair opening kinetics study of the aegPNA:DNA hydrid duplex containing a site-specific GNA-like chiral PNA monomer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:7329–7335. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anosova I., Kowal E.A., Sisco N.J., Sau S., Liao J.Y., Bala S. Structural insights into conformation differences between DNA/TNA and RNA/TNA chimeric duplexes. ChemBioChem. 2016;17:1705–1708. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201600349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Legault P., Pardi A. Unusual dynamics and pKa shift at the active site of a lead-dependent ribozyme. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:6621–6628. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ravindranathan S., Butcher S.E., Feigon J. Adenine protonation in domain B of the hairpin ribozyme. Biochemistry. 2000;39:16026–16032. doi: 10.1021/bi001976r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reiter N.J., Blad H., Abildgaard F., Butcher S.E. Dynamics in the U6 RNA intramolecular stem-loop: a base flipping conformational change. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13739–13747. doi: 10.1021/bi048815y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shrestha P., Cui Y., Wei J., Jonchhe S., Mao H. Single-molecule mechanochemical pH sensing revealing the proximity effect of hydroniums generated by an alkaline phosphatase. Anal Chem. 2018;90:1718–1724. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b03478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang L., Zhong Z., Tong C., Jia H., Liu Y., Chen G. Single-molecule mechanical folding and unfolding of RNA hairpins: effects of single A-U to a·C pair substitutions and single proton binding and implications for mRNA structure-induced −1 ribosomal frameshifting. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:8172–8184. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b02970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cao C., Jiang Y.L., Stivers J.T., Song F. Dynamic opening of DNA during the enzymatic search for a damaged base. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1230–1236. doi: 10.1038/nsmb864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao C., Jiang Y.L., Krosky D.J., Stivers J.T. The catalytic power of uracil DNA glycosylase in the opening of thymine base pairs. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13034–13035. doi: 10.1021/ja062978n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parker J.B., Bianchet M.A., Krosky D.J., Friedman J.I., Amzel L.M., Stivers J.T. Enzymatic capture of an extrahelical thymine in the search for uracil in DNA. Nature. 2007;449:433–437. doi: 10.1038/nature06131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedman J.I., Majumdar A., Stivers J.T. Nontarget DNA binding shapes the dynamic landscape for enzymatic recognition of DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3493–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee Y.M., Kim H.E., Park C.J., Lee A.R., Ahn H.C., Cho S.J. NMR study on the B-Z junction formation of DNA duplexes induced by Z-DNA binding domain of human ADAR1. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:5276–5283. doi: 10.1021/ja211581b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kang Y.M., Bang J., Lee E.H., Ahn H.C., Seo Y.J., Kim K.K. NMR spectroscopic elucidation of the B-Z transition of a DNA double helix induced by the Zα domain of the human ADAR1. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:11485–11491. doi: 10.1021/ja902654u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee J.H., Jucker F., Pardi A. Imino proton exchange rates imply an induced-fit binding mechanism for the VEGF165-targeted aptamer, Macugen. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1835–1839. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu M., Mao X., Ye C., Huang H., Nicholson J.K., Lindon J.C. Improved WATERGATE pulse sequences for solvent suppression in NMR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 1998;132:125–129. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hwang T.L., Mori S., Shaka A.J., van Zijl P.C.M. Application of phase-modulated CLEAN chemical EXchange spectroscopy (CLEANEX-PM) to detect water−protein proton exchange and intermolecular NOEs. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:6203–6204. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rennella E., Sára T., Juen M., Wunderlich C., Imbert L., Solyom Z. RNA binding and chaperone activity of the E. coli cold-shock protein CspA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:4255–4268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strebitzer E., Rangadurai A., Plangger R., Kremser J., Juen M.A., Tollinger M. 5-Oxyacetic acid modification destabilizes double helical stem structures and favors anionic Watson-crick like cmo5U-G base pairs. Chem A Eur J. 2018;24:18903–18906. doi: 10.1002/chem.201805077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee Y.M., Lee E.H., Seo Y.J., Kang Y.M., Ha J.H., Kim H.E. Measurement of hydrogen exchange times of the RNA imino protons using by phase-modulated CLEAN chemical exchange spectroscopy. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2009;30:2197–2198. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnston P.D., Figueroa N., Redfield A.G. Real-time solvent exchange studies of the imino and amino protons of yeast phenylalanine transfer RNA by Fourier transform NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:3130–3134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.7.3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Figueroa N., Keith G., Leroy J.L., Plateau P., Roy S., Guéron M. NMR study of slowly exchanging imino protons in yeast tRNAasp. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:4330–4333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.14.4330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vermeulen A., McCallum S.A., Pardi A. Comparison of the global structure and dynamics of native and unmodified tRNAval. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6024–6033. doi: 10.1021/bi0473399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheong C., Moore P.B. Solution structure of an unusually stable RNA tetraplex containing G- and U-quartet structures. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8406–8414. doi: 10.1021/bi00151a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nozinovic S., Fürtig B., Jonker H.R., Richter C., Schwalbe H. High-resolution NMR structure of an RNA model system: the 14-mer cUUCGg tetraloop hairpin RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:683–694. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee J.H. Hydrogen-deuterium exchange of Tetrahymena group I ribozyme. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2007;28:1643–1644. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Geier G.E., Modrich P. Recognition sequence of the dam methylase of Escherichia coli K12 and mode of cleavage of Dpn I endonuclease. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:1408–1413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lu M., Campbell J.L., Boye E., Kleckner N. SeqA: a negative modulator of replication initiation in E. coli. Cell. 1994;77:413–426. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Engel J.D., von Hippel P.H. Effects of methylation on the stability of nucleic acid conformations: studies at the monomer level. Biochemistry. 1974;13:4143–4158. doi: 10.1021/bi00717a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Micura R., Pils W., Höbartner C., Grubmayr K., Ebert M.O., Jaun B. Methylation of the nucleobases in RNA oligonucleotides mediates duplex-hairpin conversion. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3997–4005. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.19.3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roost C., Lynch S.R., Batista P.J., Qu K., Chang H.Y., Kool E.T. Structure and thermodynamics of N6-methyladenosine in RNA: a spring-loaded base modification. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2107–2115. doi: 10.1021/ja513080v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guarne A., Zhao Q., Ghirlando R., Yang W. Insights into negative modulation of E. coli replication initiation from the structure of SeqA-hemimethylated DNA complex. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nsb857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bae S.H., Cheong H.K., Cheong C., Kang S., Hwang D.S., Choi B.S. Structure and dynamics of hemimethylated GATC sites: implications for DNA-SeqA recognition. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45987–45993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mitchell D.L. (1988) the relative cytotoxicity of (6-4) photoproducts and cyclobutane dimers in mammalian cells. Photochem Photobiol. 1988;48:51–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1988.tb02785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Park C.J., Lee J.H., Choi B.S. Functional insights gained from structural analyses of DNA duplexes that contain UV-damaged photoproducts. Photochem Photobiol. 2007;83:187–195. doi: 10.1562/2006-02-28-IR-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Laat W.L., Jaspers N.G., Hoeijmakers J.H. Molecular mechanism of nucleotide excision repair. Genes Dev. 1999;13:768–785. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sugasawa K., Ng J.M., Masutani C., Iwai S., van der Spek P.J., Eker A.P. Xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein complex is the initiator of global genome nucleotide excision repair. Mol Cell. 1988;2:223–232. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sugasawa K., Okamoto T., Shimizu Y., Masutani C., Iwai S., Hanaoka F. A multistep damage recognition mechanism for global genomic nucleotide excision repair. Genes Dev. 2001;15:507–521. doi: 10.1101/gad.866301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee J.H., Park C.J., Shin J.S., Ikegami T., Akutsu H., Choi B.S. NMR structure of the DNA decamer duplex containing double T·G mismatches of cis-syn cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer: implications for DNA damage recognition by the XPC-hHR23B complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2474–2481. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carrington J.C., Ambros V. Role of microRNAs in plant and animal development. Science. 2003;301:336–338. doi: 10.1126/science.1085242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou C.M., Wang J.W. Regulation of flowering time by microRNAs. J Genet Genomics. 2013;40:211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim W., Ahn J.H. MicroRNA-target interactions: important signaling modules regulating flowering time in diverse plant species. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2014;33:470–485. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim J.J., Lee J.H., Kim W., Jung H.S., Huijser P., Ahn J.H. The microRNA156-SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE3 module regulates ambient temperature-responsive flowering via FLOWERING LOCUS T in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:461–478. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.192369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wu G., Poethig R.S. Temporal regulation of shoot development in Arabidopsis thaliana by miR156 and its target SPL3. Development. 2006;133:3539–3547. doi: 10.1242/dev.02521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Been M.D., Cech T.R. One binding-site determines sequence specificity of Tetrahymena pre-ribosomal-RNA self-splicing, transsplicing, and RNA enzyme-activity. Cell. 1986;47:207–216. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90443-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Karbstein K., Carroll K.S., Herschlag D. (2002) probing the Tetrahymena group I ribozyme reaction in both directions. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11171–11183. doi: 10.1021/bi0202631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bartley L.E., Zhuang X., Das R., Chu S., Herschlag D. Exploration of the transition state for tertiary structure formation between an RNA helix and a large structured RNA. J Mol Biol. 2003;328:1011–1026. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Adams P.L., Stahley M.R., Kosek A.B., Wang J., Strobel S.A. Crystal structure of a self-splicing group I intron with both exons. Nature. 2004;430:45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature02642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Golden B.L., Kim H., Chase E. Crystal structure of a phage Twort group I ribozyme-product complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:82–89. doi: 10.1038/nsmb868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Herbert A., Rich A. The biology of left-handed Z-DNA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11595–11598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.11595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Herbert A., Rich A. Left-handed Z-DNA: structure and function. Genetica. 1999;106:37–47. doi: 10.1023/a:1003768526018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rich A., Zhang S. Z-DNA: the long road to biological function. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:566–572. doi: 10.1038/nrg1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schwartz T., Rould M.A., Lowenhaupt K., Herbert A., Rich A. Crystal structure of the Zα domain of the human editing enzyme ADAR1 bound to left-handed Z-DNA. Science. 1999;284:1841–1845. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schwartz T., Behlke J., Lowenhaupt K., Heinemann U., Rich A. Structure of the DLM-1-Z-DNA complex reveals a conserved family of Z-DNA-binding proteins. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:761–765. doi: 10.1038/nsb0901-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ha S.C., Lokanath N.K., van Quyen D., Wu C.A., Lowenhaupt K., Rich A. A poxvirus protein forms a complex with left-handed Z-DNA: crystal structure of a Yatapoxvirus Zα bound to DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14367–14372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405586101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim D., Hur J., Park K., Bae S., Shin D., Ha S.C. Distinct Z-DNA binding mode of a PKR-like protein kinase containing a Z-DNA binding domain (PKZ) Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:5937–5948. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee E.H., Seo Y.J., Ahn H.C., Kang Y.M., Kim H.E., Lee Y.M. NMR study of hydrogen exchange during the B-Z transition of a DNA duplex induced by the Zα domain of yatapoxvirus E3L. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:4453–4457. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim H.E., Ahn H.C., Lee Y.M., Lee E.H., Seo Y.J., Kim Y.G. The Zβ domain of human DAI binds to Z-DNA via a novel B-Z transition pathway. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:772–778. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Seo Y.J., Ahn H.C., Lee E.H., Bang J., Kang Y.M., Kim H.E. Sequence discrimination of the Zα domain of human ADAR1 during B-Z transition of DNA duplexes. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:4344–4350. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lee A.R., Park C.J., Cheong H.K., Ryu K.S., Park J.W., Kwon M.Y. Solution structure of Z-DNA binding domain of PKR-like protein kinase from Carassius auratus and quantitative analyses of intermediate complex during B-Z transition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:2936–2948. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ha S.C., Lowenhaupt K., Rich A., Kim Y.G., Kim K.K. Crystal structure of a junction between B-DNA and Z-DNA reveals two extruded bases. Nature. 2005;437:1183–1186. doi: 10.1038/nature04088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee Y.M., Kim H.E., Lee E.H., Seo Y.J., Lee A.R., Lee J.H. NMR investigation on the DNA binding mode and B-Z transition pathway of the Zα domain of human ADAR1. Biophys Chem. 2013;172:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ng E.W., Shima D.T., Calias P., Cunningham E.T., Jr., Guyer D.R., Adamis A.P. Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:123–132. doi: 10.1038/nrd1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ferrara N., Gerber H.P., LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ruckman J., Green L.S., Beeson J., Waugh S., Gillette W.L., Henninger D.D. 2’-Fluoropyrimidine RNA-based aptamers to the 165-amino acid form of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF165) J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20556–20567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee J.H., Canny M.D., de Erkenez A., Krilleke D., Ng Y.S., Shima D.T. A therapeutic aptamer inhibits angiogenesis by specifically targeting the heparin binding domain of VEGF165. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18902–18907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509069102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nielsen P.E., Egholm M., Berg R.H., Buchardt O. Sequence-selective recognition of DNA by strand displacement with a thymine-substituted polyamide. Science. 1991;254:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1962210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Egholm M., Buchardt O., Nielsen P.E. Peptide nucleic acids (PNA). Oligonucleotide analogs with an achiral peptide backbone. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:1895–1897. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ok T., Lee J., Jung C., Lim J., Park C.M., Lee J.H. GNA/aegPNA chimera loaded with RNA binding preference. Chem Asian J. 2011;6:1996–1999. doi: 10.1002/asia.201100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]