Abstract

Aims

Patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease (CHD‐PAH) after defect correction have a poor prognosis compared with other CHD‐PAH patients. Therefore, it is important that these patients are treated as early and effectively as possible. Evidence supporting the use of PAH therapies in patients with corrected CHD‐PAH from randomised controlled trials is limited. The purpose of these analyses was to characterise the corrected CHD‐PAH patients from the GRIPHON study and examine the response to selexipag.

Methods and results

Out of the 110 patients diagnosed with corrected CHD‐PAH, 55 had atrial septal defects, 38 had ventricular septal defects, 14 had persistent ducti arteriosus, and 3 had defects not further specified. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the primary composite endpoint were calculated using Cox proportional hazard models. Compared with the non‐CHD patients from GRIPHON, patients with corrected CHD‐PAH were slightly younger, with a greater proportion being treatment‐naive and in World Health Organization functional class I/II. The rate of the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality was lower in patients with corrected CHD‐PAH who were treated with selexipag compared with those treated with placebo (HR 0.58; 95% CI 0.25, 1.37). The most common adverse events were those known to be related to selexipag.

Conclusions

These post‐hoc analyses of GRIPHON provide valuable information about a large population of patients with corrected CHD‐PAH, and suggest that selexipag may delay disease progression and was well‐tolerated in patients with corrected CHD‐PAH.

Keywords: Selexipag, Pulmonary arterial hypertension, Congenital heart disease, Disease progression, Randomised controlled trial, Efficacy

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) associated with congenital heart disease (CHD) (CHD‐PAH) is one of the most frequent aetiologies of PAH.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Due to improvements in the diagnosis and surgical treatment of paediatric CHD, the number of adults living with CHD‐PAH is growing.7 CHD‐PAH characterised by shunt lesions is a heterogeneous population consisting of four subgroups: (i) Eisenmenger's syndrome; (ii) PAH associated with predominant systemic‐to‐pulmonary shunts; (iii) PAH with small/coincidental defects; and (iv) PAH after defect correction (corrected CHD‐PAH).8 Patients with CHD‐PAH are generally perceived as having a better survival than patients with idiopathic PAH (IPAH).9 However, patients with corrected CHD‐PAH seem to have a poor prognosis compared with other types of CHD‐PAH,5, 8, 10 and are reported to have a survival comparable to that of IPAH patients.5 Therefore, there is a need for early and effective management of patients with corrected CHD‐PAH.

Evidence supporting the use of PAH therapies in patients with corrected CHD‐PAH has recently started to emerge.10, 11, 12 Two recent large PAH randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (SERAPHIN and PATENT) enrolled 62 and 35 patients, respectively, with corrected CHD‐PAH; subgroup analyses revealed beneficial effects of PAH therapy in these patients.11, 12

The long‐term, event‐driven, randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase III GRIPHON trial, which evaluated the selective IP prostacyclin receptor agonist selexipag, enrolled 110 patients with corrected CHD‐PAH. In the overall GRIPHON population, selexipag reduced the risk of the primary composite outcome of morbidity/mortality by 40% (P < 0.001) compared with placebo13; the treatment effect was consistent in the corrected CHD‐PAH subgroup. The current analyses further examined the efficacy, safety and tolerability of selexipag in this large population of patients with corrected CHD‐PAH enrolled in GRIPHON.

Methods

Study population

GRIPHON was a global, double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled, event‐driven, phase III trial (NCT01106014) described in detail elsewhere.13 Patients (18–75 years) with a diagnosis of PAH confirmed by right heart catheterisation and a 6‐minute walk distance (6MWD) of 50–450 m at baseline were eligible.13 The study enrolled patients with corrected CHD‐PAH who had repaired (for ≥ 1 year) congenital simple systemic‐to‐pulmonary shunts, and patients with IPAH or heritable PAH, or PAH associated with connective tissue disease, human immunodeficiency virus infection or drug/toxin exposure.13 Patient aetiology was specified by the investigator. Patients with corrected CHD‐PAH were enrolled at 56 sites in 26 countries. Eligible patients were treatment‐naive or receiving a phosphodiesterase‐5 inhibitor, an endothelin receptor antagonist, or both, at doses that were stable for at least 3 months prior to randomisation.13 All patients provided written informed consent.13

Study design

Patients were randomised (1:1) to receive selexipag or placebo twice daily (b.i.d.). During a 12‐week titration period, study drug was initiated at 200 μg b.i.d. and titrated weekly in increments of 200 μg b.i.d. to the highest tolerated dose. The maximum allowed dose was 1600 μg b.i.d.13 At the end of the titration period, patients entered the maintenance phase. Dose increases were allowed at scheduled visits from Week 26; dose reductions were allowed at any time.13 The individualised maintenance dose (IMD) was the dose that the patient received for the longest duration in the study. IMDs were categorised into three pre‐specified dose groups: low (200 and 400 μg b.i.d.), medium (600, 800 and 1000 μg b.i.d.) or high (1200, 1400 and 1600 μg b.i.d.).13 The double‐blind treatment period ended when the patient experienced a primary endpoint event, prematurely discontinued study drug, or when the study ended (for patients with no primary endpoint event).13 The study ended when the pre‐specified number of 331 primary endpoint events was reached.13 GRIPHON was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by local institutional review boards or independent ethics committees.13

Outcome measures

The primary composite endpoint was the time from randomisation to first morbidity/mortality event up to the end of double‐blind treatment. Morbidity events included disease progression, or worsening of PAH that resulted in hospitalisation, initiation of parenteral prostanoid therapy or long‐term oxygen therapy, or need for lung transplantation or balloon atrial septostomy.13 Disease progression was defined as a decrease of ≥ 15% in 6MWD from baseline (confirmed by a second test on a different day), and worsening in World Health Organization functional class (WHO FC) for patients in WHO FC II or III at baseline or the need for additional PAH therapy for patients in WHO FC III or IV at baseline.13 All primary endpoint events were adjudicated by a blinded independent committee.13 Secondary endpoints included change in 6MWD from baseline to Week 26 and death from any cause up to the end of the study.13 Exploratory endpoints included the change in N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) level from baseline to Week 26.13 Adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) were recorded throughout the study and up to 7 and 30 days, respectively, after the end of treatment.13

Statistical analyses

Exploratory post‐hoc analyses were conducted on the subgroup with corrected CHD‐PAH from GRIPHON. Kaplan–Meier estimates by treatment arm were calculated for the primary composite endpoint. Cox proportional‐hazard models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).13 A non‐parametric analysis of covariance, with adjustment for the respective baseline value, was used to analyse changes from baseline in 6MWD and NT‐proBNP levels. Values at Week 26 were imputed as 0 m if the patient was unable to walk, or as 10 m (second lowest observed 6MWD value at Week 26 irrespective of treatment) if the former rule did not apply.13 The analysis of NT‐proBNP levels was performed on observed data (40 placebo and 53 selexipag patients).13

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the 1156 patients enrolled in GRIPHON, 110 patients were diagnosed with corrected CHD‐PAH, including 55 (50%) patients with atrial septal defects, 38 (34%) with ventricular septal defects, 14 (13%) with persistent ducti arteriosus, and 3 (3%) with defects not further specified. Of the 110 patients, 50 were randomised to receive placebo and 60 to receive selexipag. Baseline characteristics of corrected CHD‐PAH patients were balanced between treatment arms, with the exception of NT‐proBNP level (median of 471 ng/L for placebo vs. 286 ng/L for selexipag; Table 1). With a mean (standard deviation) age of 40.3 (15.1) years, corrected CHD‐PAH patients were younger than patients in the non‐CHD population [mean age of 48.9 (15.2) years]. Furthermore, in comparison with the non‐CHD population, a greater proportion of patients with corrected CHD‐PAH were in WHO FC I/II and treatment‐naive at baseline, with fewer corrected CHD‐PAH patients receiving combination therapy. There were also regional differences between the corrected CHD‐PAH group and the non‐CHD population.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease after defect correctiona

| Characteristic | Corrected CHD‐PAH population | Non‐CHD population (n = 1046) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 50) | Selexipag (n = 60) | Overall (n = 110) | ||

| Female sex, n (%) | 42 (84.0) | 46 (76.7) | 88 (80.0) | 835 (79.8) |

| Age years, mean ± SD | 40.3 ± 14.8 | 40.2 ± 15.4 | 40.3 ± 15.1 | 48.9 ± 15.2 |

| Geographic region, n (%) | ||||

| Asia | 17 (34.0) | 15 (25.0) | 32 (29.1) | 196 (18.7) |

| Eastern Europe | 21 (42.0) | 24 (40.0) | 45 (40.9) | 259 (24.8) |

| Latin America | 4 (8.0) | 8 (13.3) | 12 (10.9) | 98 (9.4) |

| North America | 2 (4.0) | 8 (13.3) | 10 (9.1) | 183 (17.5) |

| Western Europe/Australia | 6 (12.0) | 5 (8.3) | 11 (10.0) | 310 (29.6) |

| Time since diagnosis of PAHb, years, mean ± SD | 3.5 ± 5.5 | 3.6 ± 6.1 | 3.6 ± 5.8 | 2.3 ± 3.3 |

| WHO FC, n (%) | ||||

| I | – | 1 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) | 8 (0.8) |

| II | 28 (56.0) | 38 (63.3) | 66 (60.0) | 463 (44.3) |

| III | 22 (44.0) | 21 (35.0) | 43 (39.1) | 564 (53.9) |

| IV | – | – | – | 11 (1.1) |

| 6MWD, m, mean ± SD | 358.7 ± 72.9 | 366.6 ± 71.4 | 363.0 ± 71.9 | 352.2 ± 80.8 |

| Use of medications for PAH, n (%) | 35 (70.0) | 40 (66.7) | 75 (68.2) | 845 (80.8) |

| None | 15 (30.0) | 20 (33.3) | 35 (31.8) | 201 (19.2) |

| ERA | 7 (14.0) | 11 (18.3) | 18 (16.4) | 152 (14.5) |

| PDE‐5i | 18 (36.0) | 19 (31.7) | 37 (33.6) | 337 (32.2) |

| ERA and PDE‐5i | 10 (20.0) | 10 (16.7) | 20 (18.2) | 356 (34.0) |

| NT‐proBNPc, ng/L, median (Q1, Q3) | 471 (186, 1390) | 286 (99, 752) | 336 (124, 986.5) | 593.5 (196, 1654) |

6MWD, 6‐minute walk distance; CHD, congenital heart disease; ERA, endothelin receptor antagonist; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; PDE‐5i, phosphodiesterase‐5 inhibitor; SD, standard deviation; WHO FC, World Health Organization functional class.

Testing of baseline characteristics showed there were (i) no significant differences (P > 0.05) between placebo and selexipag at baseline in the corrected CHD‐PAH patients with the exception of NT‐proBNP (P < 0.05), and (ii) significant differences (P < 0.05) between the corrected CHD‐PAH and non‐CHD populations with the exception of sex and 6MWD (P > 0.05) [comparisons to placebo were conducted using Fisher's exact test (sex, geographic region, WHO FC and use of medications for PAH), unadjusted analysis of variance (age and time since diagnosis of PAH) and Wilcoxon‐Mann‐Whitney test (6MWD and NT‐proBNP)].

Confirmed by right heart catheterisation.

Includes all patients with a baseline assessment: for the corrected CHD‐PAH population, n = 49 for placebo and n = 59 for selexipag; for the overall non‐CHD population, n = 1034.

Treatment exposure and dose

The median (range) duration of placebo and selexipag administration was 78.6 (0.7–179.0) and 76.9 (2.3–164.9) weeks, respectively, in corrected CHD‐PAH patients. Within the corrected CHD‐PAH population, 36.7%, 28.3% and 35.0% of selexipag‐treated patients had their IMD in the low‐, medium‐ and high‐dose groups, respectively (online supplementary Table S1).

Efficacy outcomes

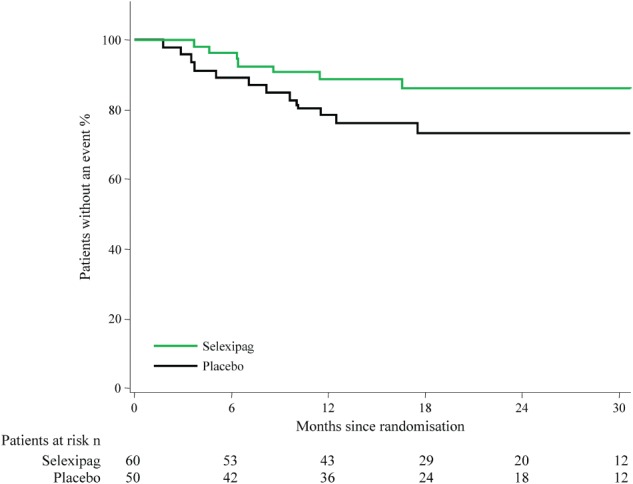

In the corrected CHD‐PAH population, 13 (26%) patients in the placebo arm and 9 (15%) patients in the selexipag arm experienced a primary endpoint event (Table 2), as previously reported.13 The rate of the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality was lower in patients treated with selexipag compared with those treated with placebo (HR 0.58; 95% CI 0.25, 1.37) (Figure 1), which is consistent with that in the overall GRIPHON population (interaction P‐value in the PAH aetiology subgroups 0.98).13 Among patients with corrected CHD‐PAH, hospitalisation for worsening of PAH and disease progression accounted for the majority of primary endpoint events (90.9%) (Table 2); this was also observed in the overall population.13 By the study end, seven patients with corrected CHD‐PAH had died (5 in the placebo group and 2 in the selexipag group) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Events related to pulmonary arterial hypertension and death for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease after defect correction

| Placebo (n = 50) | Selexipag (n = 60) | Overall (n = 110) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality up to the end of treatment | |||

| All events, n (%) | 13 (26.0) | 9 (15.0) | 22 (20.0) |

| Hospitalisation for worsening of PAH | 7 (14.0) | 8 (13.3) | 15 (13.6) |

| Disease progression | 4 (8.0) | 1 (1.7) | 5 (4.5) |

| Death from any cause | 2 (4.0) | – | 2 (1.8) |

| Initiation of parenteral prostanoid therapy or long‐term O2 therapy for worsening PAH | – | – | – |

| Need for lung transplantation or balloon atrial septostomy for worsening of PAH | – | – | – |

| Secondary endpoint of all‐cause death up to the end of the study | |||

| Death from any cause, n (%) | 5 (10.0) | 2 (3.3) | 7 (6.4) |

PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Figure 1.

Effect of selexipag on the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease after defect correction.

At Week 26, in patients with corrected CHD‐PAH, the 6MWD increased by a median of 2 m from baseline to Week 26 in the placebo group and 11 m in the selexipag group (treatment effect: 15 m, 95% CI −7, 40) (Table 3). For NT‐proBNP, there was a treatment effect of −8 ng/L (95% CI −88, 69) for selexipag vs. placebo (Table 3).

Table 3.

Change in 6‐minute walk distance and N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide from baseline to Week 26 for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease after defect correction

| Placebo (n = 50) | Selexipag (n = 60) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median at baseline (Q1, Q3) | Median at 26 weeks (Q1, Q3) | Median change (Q1, Q3) | Median at baseline (Q1, Q3) | Median at 26 weeks (Q1, Q3) | Median change (Q1, Q3) | Treatment effect (CI)a | |

| 6MWD, m | 369 (320, 423) | 357 (240, 412) | 2 (−39, 37) | 379 (333, 421) | 387 (346, 431) | 11 (−16, 40) | 15 (−7, 40) |

| NT‐proBNPb, ng/L | 426 (151, 1280) | 518 (171, 1065) | −11 (−107, 81) | 286 (98, 649) | 236 (97, 684) | −4 (−89, 52) | −8 (−88, 69) |

6MWD, 6‐minute walk distance; CI, confidence interval; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide. Values at Week 26 were imputed as 0 m if the patient was unable to walk, or as 10 m (second lowest observed 6MWD value at Week 26 irrespective of treatment) if the former rule did not apply; 20% of patients in the placebo group, and 10% in the selexipag group had imputed values at Week 26.13 For NT‐proBNP values, only patients with a non‐missing value at both baseline and at the Week 26 visit are included.

Point estimate for location shift as estimated by Hodges–Lehmann method (95% CI reported for 6MWD and NT‐proBNP).

There were fewer patients (40 placebo and 53 selexipag) with NT‐proBNP data.

Safety and tolerability

In patients with corrected CHD‐PAH, 4 (8.0%) placebo patients and 5 (8.3%) selexipag patients discontinued their treatment prematurely due to an AE (Table 4); 7.1% placebo and 14.3% selexipag in the overall GRIPHON population13 prematurely discontinued their treatment due to an AE. The frequency of AEs reported in the placebo (98.0%) and selexipag (95.0%) groups was comparable. This is similar to that in the overall GRIPHON population (96.9% in placebo and 98.3% in selexipag).13 The most common AEs in the selexipag‐treated group in corrected CHD‐PAH patients were headache, myalgia and diarrhoea. The proportion of patients with corrected CHD‐PAH who reported ≥ 1 SAE was similar in the selexipag (30.0%) and placebo (32.0%) groups. No SAEs were reported more frequently in the selexipag group compared with the placebo group (with > 2% difference in frequency between the selexipag and placebo groups). AEs associated with therapies that target the prostacyclin pathway were more frequently reported during the titration period than the maintenance period (Table 5).

Table 4.

Most frequent adverse events in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease after defect correction

| Variable | Placebo (n = 50) | Selexipag (n = 60) |

|---|---|---|

| Adverse events, n | 225 | 411 |

| Patients with ≥ 1 AE, n (%) | 49 (98.0) | 57 (95.0) |

| Patients with ≥ 1 SAE, n (%) | 16 (32.0) | 18 (30.0) |

| Patients with AE leading to discontinuation of study drug, n (%) | 4 (8.0) | 5 (8.3) |

| AEsa, n (%) | ||

| Headache | 19 (38.0) | 40 (66.7) |

| Myalgia | 5 (10.0) | 19 (31.7) |

| Diarrhoea | 2 (4.0) | 21 (35.0) |

| Pain in jaw | 2 (4.0) | 18 (30.0) |

| Nausea | 1 (2.0) | 18 (30.0) |

| Worsening of PAH | 11 (22.0) | 7 (11.7) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 9 (18.0) | 8 (13.3) |

| Dyspnoea | 7 (14.0) | 6 (10.0) |

| Peripheral oedema | 7 (14.0) | 6 (10.0) |

| Fatigue | 4 (8.0) | 8 (13.3) |

| Arthralgia | – | 11 (18.3) |

| Dizziness | 2 (4.0) | 8 (13.3) |

| Flushing | 2 (4.0) | 8 (13.3) |

| Vomiting | – | 7 (11.7) |

AE, adverse event; SAE, serious adverse event.

AEs listed are those that occurred in more than 10% of the patients in any study group during the double‐blind period and up to 7 days after placebo or selexipag was discontinued.

Table 5.

Prostacyclin‐associated adverse events reported in the study titration and maintenance periods for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease after defect correction

| Titration period | Maintenance period | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 50) | Selexipag (n = 60) | Placeboa (n = 46) | Selexipaga (n = 59) | |

| Exposure to double‐blind treatment, weeks, median (range) | 12.4 (0.7–12.4) | 12.4 (2.3–12.4) | 73.4 (2.9–166.6) | 64.6 (1.9–152.4) |

| Patients with ≥ 1 prostacyclin‐associated AE, n (%) | 24 (48.0) | 53 (88.3) | 14 (30.4) | 41 (69.5) |

| AE, n (%) | ||||

| Headache | 17 (34.0) | 40 (66.7) | 8 (17.4) | 25 (42.4) |

| Diarrhoea | 1 (2.0) | 18 (30.0) | 1 (2.2) | 13 (22.0) |

| Myalgia | 4 (8.0) | 17 (28.3) | 3 (6.5) | 12 (20.3) |

| Pain in jaw | 1 (2.0) | 17 (28.3) | 2 (4.3) | 13 (22.0) |

| Nausea | 1 (2.0) | 15 (25.0) | – | 9 (15.3) |

| Arthralgia | – | 9 (15.0) | – | 8 (13.6) |

| Flushing | 2 (4.0) | 7 (11.7) | 1 (2.2) | 5 (8.5) |

| Pain in extremity | 4 (8.0) | 5 (8.3) | 3 (6.5) | 6 (10.2) |

| Vomiting | – | 5 (8.3) | – | 3 (5.1) |

| Dizziness | 1 (2.0) | 3 (5.0) | 1 (2.2) | 5 (8.5) |

| Temporomandibular joint syndrome | – | 2 (3.3) | – | 2 (3.4) |

AE, adverse event.

A patient with multiple occurrences of an AE during one treatment period is counted only once in the AE category for that treatment and period.

Among the patients randomly assigned to each treatment arm, 4 in the placebo group and 1 in the selexipag group did not receive study treatment in the maintenance phase.

Discussion

GRIPHON included the largest population of patients with corrected CHD‐PAH evaluated in a RCT to date. In these patients, the treatment effect of selexipag on the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality was consistent with that in the overall population13 and selexipag was well tolerated. These results contribute to the small but growing body of evidence that corrected CHD‐PAH patients benefit from PAH therapy.11, 12, 14, 15, 16

There were differences between corrected CHD‐PAH patients and the non‐CHD population.13 Patients with corrected CHD‐PAH were younger, more likely to be in WHO FC I/II and less likely to be on background therapy. The greater proportion of patients in WHO FC I/II imply that corrected CHD‐PAH patients are less functionally impaired at enrolment than those with other types of PAH. As the European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of adult CHD suggest lifelong and regular follow‐up, even in the case of successful correction,17 it may be possible that CHD patients who develop PAH are diagnosed at an earlier stage of PAH than other types of PAH, therefore presenting less physically impaired at enrolment. The lower proportion of corrected CHD‐PAH patients on background therapy may reflect geographical differences between these patients and the overall study population, as a higher proportion of patients with corrected CHD were enrolled in regions where access to therapies may be limited by lack of regulatory approval or reimbursement. It can also be speculated that CHD patients who subsequently develop PAH may be less likely to be treated if there is a perception among clinicians that these patients have a less severe disease than other forms of PAH.

Descriptive analysis of the primary endpoint Kaplan–Meier curves showed that patients with corrected CHD‐PAH displayed slower disease progression than the overall study population.13 Although this may give the perception of a less severe disease in this patient group, other analyses have shown corrected CHD‐PAH patients to have a similarly poor prognosis5 and similar haemodynamic profile18, 19 to IPAH patients when the shunt is closed. The right heart loses its ability to decompress though a right‐to‐left shunt and is prone to failure, similar to IPAH. Furthermore, data from a long‐term retrospective analysis of 192 CHD‐PAH patients indicate that corrected CHD‐PAH patients had a worse outcome than those with other forms of CHD‐PAH.10 Possible reasons why patients in our study had a better outcome than expected include the exclusion of patients with complex defects, as morbidity and mortality are reported to be high in this group of patients.20, 21 Furthermore, the length of time since defect correction is not known but may have impacted on the rate of disease progression. In corrected CHD‐PAH patients, the effect of selexipag on the risk of the composite primary endpoint of morbidity/mortality was comparable to that in the overall population. These results on long‐term outcomes add to those from SERAPHIN11 and provide additional evidence for the use of PAH therapy in patients with corrected CHD‐PAH.

The effect of selexipag on the secondary endpoint of change from baseline to Week 26 in 6MWD was similar between corrected CHD‐PAH patients and the overall study population,13 but lower than that in the post‐hoc subgroup analysis of corrected CHD‐PAH patients treated with riociguat in PATENT.12 The modest improvement in 6MWD in corrected CHD‐PAH patients in GRIPHON may reflect the large percentage of patients who were receiving PAH therapy at baseline and who were in WHO FC II, as well as the prevalent nature of the patients. Reasons for the difference observed between the 6MWD results in this analysis and PATENT are unknown, but may depend on patient variables, such as the length of time since surgical repair, or differences in the proportion of CHD patients taking background therapy (68.2% in GRIPHON vs. 43% in PATENT12). There was no significant decrease in NT‐proBNP levels with selexipag treatment in patients with corrected CHD‐PAH in contrast to the overall GRIPHON population13 and PATENT.12 This may be because of the low baseline NT‐proBNP levels in GRIPHON, along with the imbalance in baseline NT‐proBNP levels observed between the placebo and selexipag groups.

Using the approach of individualised dosing based on tolerability, corrected CHD‐PAH patients were distributed relatively evenly amongst the three dose groups. This is consistent with what was observed in the overall study,13 supporting the same titration approach in both populations. In patients with corrected CHD‐PAH, the tolerability of selexipag was comparable to that of the overall study population.13 Patients with corrected CHD‐PAH had a longer treatment exposure than the overall population; contributors to this include a lower proportion of patients exiting due to both primary endpoint events and AEs in selexipag‐treated corrected CHD‐PAH patients.13 The most frequently reported AEs are suggestive of selexipag's mode of action as an IP receptor agonist. There were no new or unexpected safety findings in corrected CHD‐PAH patients, supporting the safety of selexipag treatment in this population.

This analysis has several strengths in comparison with other RCTs that included corrected CHD‐PAH patients.11, 12, 14 Firstly, the study population was larger and this study provided long‐term data. Furthermore, the majority of patients received PAH therapy at baseline. As PAH patients are now frequently treated with combination therapy,22 the GRIPHON population reflects patients in clinical practice.

Investigating the consistency of the selexipag treatment effect on the primary endpoint across subgroups, including corrected CHD‐PAH patients, was a pre‐specified analysis. However, the additional analyses of selexipag efficacy and tolerability in this patient group are post‐hoc and, therefore, not sufficiently powered for formal statistical analysis, and are exploratory in nature. Other limitations are that only patients with simple defects were enrolled and the lack of data on when patients received corrective surgery. The exact anatomy of the defect before closure and pre‐operative haemodynamic profile of these patients are also not known as the study was not designed to collect these data; this limitation is common to all clinical trials that enrol corrected CHD‐PAH patients to date. Although greater than in previous studies, the number of patients in this analysis is still relatively small, preventing any subgroup comparison between patients with different types of defects.

Conclusions

These post‐hoc analyses suggest that selexipag may delay disease progression and is well tolerated in patients with corrected CHD‐PAH. These findings add to the emerging body of evidence that PAH therapies can benefit patients with corrected CHD‐PAH.

Supporting information

Table S1. Individual maintenance dose of patients with corrected CHD‐PAH.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Ruth Lloyd from nspm ltd for medical writing assistance, funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

Funding

This work was supported by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Allschwil, Switzerland.

Conflict of interest: M.B. reports non‐financial support, grants and personal fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd; grants and personal fees from Bayer HealthCare; and consultancy fees from Eli Lilly, Pfizer and GSK. R.N.C. consults for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd and Bayer HealthCare and has received a research grant from Bayer HealthCare. K.M.C. reports personal fees, grants and non‐financial support from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd; grants and personal fees from Bayer HealthCare and Gilead Sciences Inc; and grants from GeNO and the NIH. L.D.S. is an employee of Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd and holds stock in the parent company Johnson&Johnson. S.G. reports personal fees and non‐financial support from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer HealthCare, GSK, Novartis and Daiichi‐Sankyo, and personal fees from United Therapeutics and Pfizer. H.A.G. reports personal fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer HealthCare, Ergonex, GSK, Novartis, Pfizer, AbbVie, Bellerophon Pulse Technologies, Gilead, Medscape, MSD, OMT, Web MD Global, Deutschlandfunk and the PVRI. M.M.H. reports personal fees and non‐financial support from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, and personal fees from Pfizer, Bayer HealthCare, GSK, MSD and Gilead. I.M.L. reports grants, personal fees and non‐financial support from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd; grants and personal fees from United Therapeutics, Bayer HealthCare and GSK; and personal fees from Novartis. V.V.McL. reports grants, personal fees and non‐financial support from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer HealthCare, Gilead, and Ikaria; grants from Novartis; and personal fees from SteadyMed Therapeutics and St. Jude Medical. R.P. is an employee of Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd and holds stock in the parent company Johnson&Johnson. L.J.R. has consulted for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, United Therapeutics, Lung LLC, GeNO, and Gilead. G.S. consults for and has received grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer HealthCare, GSK, and Pfizer. O.S. has consulted for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, GSK, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, United Therapeutics and Bayer HealthCare, and has received grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, GSK, Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Bayer HealthCare. V.F.T. reports grants, personal fees and non‐financial support from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd; grants and personal fees from Bayer HealthCare, United Therapeutics, Janssen, EKOS/BTG, Arena and Reata; and personal fees from Gilead Sciences and Daiichi‐Sankyo. N.G. reports grants, personal fees and non‐financial support from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, and grants and personal fees from Bayer HealthCare, GSK, and Pfizer.

References

- 1. Badesch DB, Raskob GE, Elliott CG, Krichman AM, Farber HW, Frost AE, Barst RJ, Benza RL, Liou TG, Turner M, Giles S, Feldkircher K, Miller DP, McGoon MD. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: baseline characteristics from the REVEAL Registry. Chest 2010;137:376–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, Bertocchi M, Habib G, Gressin V, Yaici A, Weitzenblum E, Cordier JF, Chabot F, Dromer C, Pison C, Reynaud‐Gaubert M, Haloun A, Laurent M, Hachulla E, Simonneau G. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in France. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:1023–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jansa P, Jarkovsky J, Al‐Hiti H, Popelova J, Ambroz D, Zatocil T, Votavova R, Polacek P, Maresova J, Aschermann M, Brabec P, Dusek L, Linhart A. Epidemiology and long‐term survival of pulmonary arterial hypertension in the Czech Republic: a retrospective analysis of a nationwide registry. BMC Pulm Med 2014;14:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jiang X, Jing ZC. Epidemiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 2013;15:638–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alonso‐Gonzalez R, Lopez‐Guarch CJ, Subirana‐Domenech MT, Ruiz JM, Gonzalez IO, Cubero JS, del Cerro MJ, Salvador ML, Dos Subira L, Gallego P, Escribano‐Subias P, REHAP Investigators . Pulmonary hypertension and congenital heart disease: an insight from the REHAP National Registry. Int J Cardiol 2015;184:717–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dimopoulos K, Wort SJ, Gatzoulis MA. Pulmonary hypertension related to congenital heart disease: a call for action. Eur Heart J 2013;35:691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. D'Alto M, Mahadevan VS. Pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease. Eur Respir Rev 2012;21:328–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, Simonneau G, Peacock A, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Beghetti M, Ghofrani A, Gomez Sanchez MA, Hansmann G, Klepetko W, Lancellotti P, Matucci M, McDonagh T, Pierard LA, Trindade PT, Zompatori M, Hoeper M. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 2016;37:67–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giannakoulas G, Gatzoulis MA. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in congenital heart disease: current perspectives and future challenges. Hellenic J Cardiol 2016;57:218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Manes A, Palazzini M, Leci E, Bacchi Reggiani ML, Branzi A, Galiè N. Current era survival of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease: a comparison between clinical subgroups. Eur Heart J 2014;57:716–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pulido T, Adzerikho I, Channick RN, Delcroix M, Galie N, Ghofrani HA, Jansa P, Jing ZC, Le Brun FO, Mehta S, Mittelholzer CM, Perchenet L, Sastry BK, Sitbon O, Souza R, Torbicki A, Zeng X, Rubin LJ, Simonneau G, SERAPHIN Investigators . Macitentan and morbidity and mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2013;369:809–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosenkranz S, Ghofrani HA, Beghetti M, Ivy D, Frey R, Fritsch A, Weimann G, Saleh S, Apitz C. Riociguat for pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease. Heart 2015;101:1792–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sitbon O, Channick R, Chin KM, Frey A, Gaine S, Galiè N, Ghofrani HA, Hoeper MM, Lang IM, Preiss R, Rubin LJ, Di Scala L, Tapson V, Adzerikho I, Liu J, Moiseeva O, Zeng X, Simonneau G, McLaughlin VV, GRIPHON Investigators . Selexipag for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2522–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Galiè N, Barbera JA, Frost AE, Ghofrani HA, Hoeper MM, McLaughlin VV, Peacock AJ, Simonneau G, Vachiery JL, Grunig E, Oudiz RJ, Vonk‐Noordegraaf A, White RJ, Blair C, Gillies H, Miller KL, Harris JH, Langley J, Rubin LJ, AMBITION Investigators . Initial use of ambrisentan plus tadalafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2015;373:834–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sitbon O, Beghetti M, Petit J, Iserin L, Humbert M, Gressin V, Simonneau G. Bosentan for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart defects. Eur J Clin Invest 2006;36:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hislop AA, Moledina S, Foster H, Schulze‐Neick I, Haworth SG. Long‐term efficacy of bosentan in treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension in children. Eur Respir J 2011;38:70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baumgartner H, Bonhoeffer P, De Groot NM, de HF, Deanfield JE, Galiè N, Gatzoulis MA, Gohlke‐Baerwolf C, Kaemmerer H, Kilner P, Meijboom F, Mulder BJ, Oechslin E, Oliver JM, Serraf A, Szatmari A, Thaulow E, Vouhe PR, Walma E. ESC Guidelines for the management of grown‐up congenital heart disease (new version 2010): The Task Force on the Management of Grown‐Up Congenital Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2010;31:2915–2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gatzoulis MA, Alonso‐Gonzalez R, Beghetti M. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in paediatric and adult patients with congenital heart disease. Eur Respir Rev 2009;18:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barst RJ, Ivy DD, Foreman AJ, McGoon MD, Rosenzweig EB. Four‐ and seven‐year outcomes of patients with congenital heart disease‐associated pulmonary arterial hypertension (from the REVEAL Registry). Am J Cardiol 2014;113:147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Diller GP, Kempny A, Alonso‐Gonzalez R, Swan L, Uebing A, Li W, Babu‐Narayan S, Wort SJ, Dimopoulos K, Gatzoulis MA. Survival prospects and circumstances of death in contemporary adult congenital heart disease patients under follow‐up at a large tertiary centre. Circulation 2015;132:2118–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greutmann M, Tobler D, Kovacs AH, Greutmann‐Yantiri M, Haile SR, Held L, Ivanov J, Williams WG, Oechslin EN, Silversides CK, Colman JM. Increasing mortality burden among adults with complex congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis 2015;10:117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ghofrani A, Humbert M. The role of combination therapy in managing pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev 2014;23:469–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Individual maintenance dose of patients with corrected CHD‐PAH.