Abstract

The exact mechanism of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is unknown. It needs to be treated because of severe headache and impaired vision. For medically refractory patients, cerebrospinal fluid diversion, optic nerve sheath fenestration and dural venous sinus stenting is applied to relieve the symptoms. As a new therapy, the complication of dural venous stenting was a focus for operators. Here, a woman is reported with IIH who suffered from mastoiditis after stenting in the sigmoid sinus for the first time. The special local anatomy of the sigmoid sinus adjacent to the inner structure made it a noteworthy complication.

Keywords: Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, mastoiditis, dural venous sinus stenting

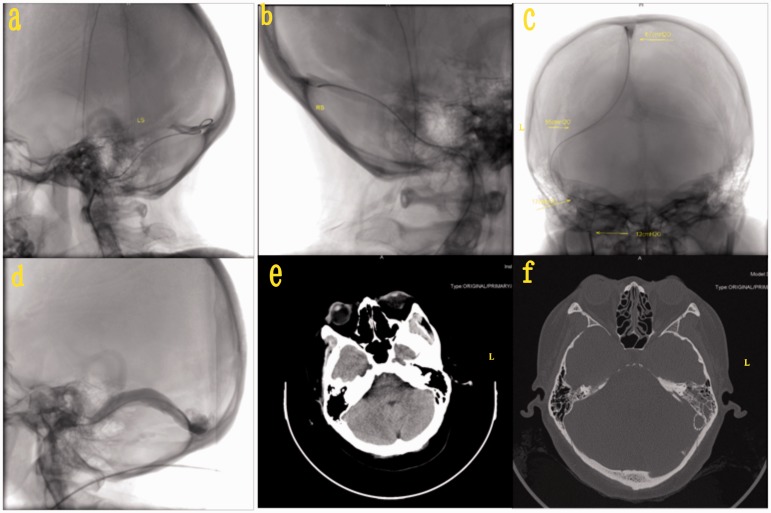

A 38-year-old woman complained of progressive poor vision for 3 years, accompanied by headache for 1 week. The woman came to hospital 3 years ago because of paroxysmal blurred vision and the symptoms lasted only a few minutes. Papillary oedema and increased hypertension of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were found after admission. Other examinations, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), immunity, testing for tumours and infection marks were all normal. With the diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), the patient received medicine for 1 week and all her symptom disappeared. Three years later, the patient came to hospital again because of blurred vision and headache. Magnetic Resonance Venogram showed stenosis of the bilateral transverse sigmoid sinus. Angiography showed eccentric stenosis of the bilateral transverse sigmoid sinus >80%, especially on the left. The pressures of the superior sagittal sinus, bilateral transverse sinus, and proximal end of right sigmoid sinus were 67, 65–67 and 12 cm water column, respectively (Figure 1(a) to (c)). A 6 × 20 mm balloon 8 atmosphere (ATM) was used to dilate the stenosis, and then a 9 × 40 mm Precise stent was located in the left transvers sigmoid sinus and opened. Under angiography, the location and adherence of the stent were good without remaining stenosis (Figure 1(d)). The pressures of the left transverse sinus and sigmoid sinus were 15 mm water column. The headache ceased quickly, but 2 days later the patient complained of an ache in the left of her head and left ear. At the same time, the patient got a fever. Physical examination found a few yellow bloody secretion in the left external auditory meatus and mastoid tenderness. Ear endoscopy showed the haematoma in the external segment of the left ear. In the inner part of the ear canal, there was a little pulse overflow. Karyocytes and pyocytes were found in routine testing of the secretion. High-resolution enhancement scanning of temporal bone showed soft tissue and fluid density in the left tympanic membrane and mastoid (Figure 1(f)), which did not exist prior to the operation (Figure 1(e)). The stent was in the left side of the sigmoid sinus. The left ossicular chain was intact, and there were no signs of bone destruction in the ossicular chain or the tympanic wall (Figure 1(f)). The morphology, structure and density of the left ear were normal. The patient received antibiotics for 5 days. Her temperature was normal and her headache was relieved, but she still had a little hearing loss. The patient was discharged, after which no more symptoms were residual 1 month later.

Figure 1.

(a) and (b) Angiography showed eccentric stenosis of bilateral transverse sigmoid before stenting. (c) The pressure of the left transverse sinus, right transverse sinus and proximal end of the right sigmoid sinus. (d) A 9 × 40 mm Precise stent was located in the left transvers sigmoid sinus. (e) and (f) Mastoid before and after stenting in computed tomography scan (yellow arrow: Precise stent; red arrow: left mastoid).

L: left side; R: right side.

IIH refers to intractable intracranial pressure.1 The CSF pressure is >25 cm H2O, with normal CSF, conventional imaging, haematology and other examinations to exclude intracranial hypertension caused for other reasons.2 The clinical manifestations usually included headache, nausea, vomiting and blurred vision. The symptoms will deteriorate gradually and may even lead to blindness.

The exact mechanism of IIH remains a topic of debate.3 A number of investigations have implicated stenosis of the dural venous sinuses as a potential contributor to IIH, especially transverse sinus stenosis, as demonstrated by MRI in 90% of patients with IIH.4

For medically refractory patients, three surgical strategies are most commonly employed: CSF diversion, optic nerve sheath fenestration and dural venous sinus stenting.5 In a meta-analysis by Satti et al. of the different therapies for IIH,5 stenting showed rare complications and fewer repeat procedures when compared with optic nerve sheath fenestration and CSF flow diversion. So it is a more promising choice for IIH treatment.

As a new therapy, almost all studies published to date for stenting in IIH have mentioned complications. Puffer et al.4 collected seven case reports and eight case series (a total of 143 patients) concerning endovascular attempts. There were three major complications (subdural haematoma requiring surgical decompression) and six minor complications (transient hearing loss, femoral pseudoaneurysm, retroperitoneal haematoma, urinary tract infection and syncopal episode. When minor complications are included, the rate becomes 9/143 (6%). Similar results were reported in the study by Starke et al., where complications were reported to be 5.4% in 185 patients.6

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a case that was complicated with mastoiditis after dural venous sinus stenting. According to the operation procedure and local anatomy, we suspect the following results. The patient's favorable petrosal bone gasification made the air chamber wrap around the majority of the sigmoid sinus. The bone wall is thin and prone to fractures by stress. In the procedure of stenting, the junction of the transverse sinus and sigmoid sinus gets the maximum stress. As mention above, the thin bone can get a tiny fracture without destroying the sinus. So, a small amount of fluid can cause otomastoiditis, but this is not serious and complete recovery after antibiotic therapy can be expected. Transient hearing loss has been reported in several case series without explanation.4 The anatomy of the sigmoid sinus adjacent to the hearing structures may be the reason both for hearing loss and otomastoiditis. This alerts us to assess the focal anatomy of the sigmoid sinus and be concerned with ear symptoms after stenting in IIH patients.

Declaration of conflict of interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Friedman DI, Jacobson DM. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology 2002; 59: 1492–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Randhawa S, Van Stavern GP. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2008; 19: 445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Julanont P, Karukote A, Ruthirago D, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: Ongoing clinical challenges and future prospects. J Pain Res 2016; 19: 87–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puffer RC, Mustafa W, Lanzino G. Venous sinus stenting for idiopathic intracranial hypertension: A review of the literature. J Neurointerv Surg 2013; 5: 483–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satti SR, Leishangthem L, Chaudry MI. Meta-analysis of CSF diversion procedures and dural venous sinus stenting in the setting of medically refractory idiopathic intracranial hypertension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 1899–18904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starke RM, Wang T, Ding D, et al. Endovascular treatment of venous sinus stenosis in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: Complications, neurological outcomes, and radiographic results. ScientificWorldJournal 2015; 2015: 140408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]