Abstract

Background & objectives:

Given that Ayushman Bharat Yojna was launched in 2018 in India, analysis of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna (RSBY) become relevant. The objective of this study was to examine the scheme design and the incentive structure under RSBY.

Methods:

The study was conducted in the districts of Patiala and Yamunanagar in the States of Punjab and Haryana, respectively (2011-2013). The mixed method study involved review of key documents; 20 in-depth interviews of key stakeholders; 399 exit interviews of RSBY and non-RSBY beneficiaries in Patiala and 353 in Yamunanagar from 12 selected RSBY empanelled hospitals; and analysis of secondary databases from State nodal agencies and district medical officers.

Results:

Insurance companies had considerable implementation responsibilities which led to conflict of interest in enrolment and empanelment. Enrolment was 15 per cent in Patiala and 42 per cent in Yamunanagar. Empanelment of health facilities was 17 (15%) in Patiala and 37 (30%) in Yamunanagar. Private-empanelled facilities were geographically clustered in the urban parts of the sub-districts. Monitoring was weak and led to breach of contracts. RSBY beneficiaries incurred out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures (₹5748); however, it was lower than that for non-RSBY (₹10667). The scheme had in-built incentives for Centre, State, insurance companies and health providers (both public and private). There were no incentives for health staff for additional RSBY activities.

Interpretation & conclusions:

RSBY has in-built incentives for all stakeholders. Some of the gaps identified in the scheme design pertained to poor enrolment practices, distribution of roles and responsibilities, fixed package rates, weak monitoring and supervision, and incurring OOP expenditure.

Keywords: Ayushman Bharat, health contracting, Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna design, RSBY incentive, social health insurance

To fulfill the vision of Health for All and Universal Health Coverage, enshrined in the National Health Policy 2017, the Government of India conceived the Ayushman Bharat (AB) scheme which was launched in 20181. It is an attempt to move from sectoral and segmented approach of health service delivery to a comprehensive need-based healthcare service. The AB scheme aims to undertake path-breaking interventions to holistically address health (covering prevention, promotion and ambulatory care), at primary, secondary and tertiary levels1. The AB scheme would subsume Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna (RSBY), and hence, analysis of RSBY will be relevant and critical at this point of time.

RSBY was introduced in 2008 by the Ministry of Labour and Employment (MoLE) in India to provide health insurance coverage to those below the poverty line (BPL). The objective of RSBY was to provide protection to BPL households from financial liabilities arising out of hospitalization when experiencing health ailments2. RSBY has an elaborate design involving a multitude of stakeholders from both the public and private sectors who are governed by contractual agreements. The insurer is contracted and paid a premium, shared by the Central Government and State Governments. A panel of public/private hospitals are contracted by the insurance company to provide inpatient services to the enrolled beneficiaries. For these services, the insurance company reimburses a fixed amount per service type to the hospitals. RSBY stands as example of using a public-private partnership (PPP) to provide both health insurance coverage and health services3.

Successful implementation of PPPs is likely to require a number of institutional features which may be absent in developing country settings4. These include the capacity of governments to manage contracts, regulate private providers, help raise capital and ensure a transparent procurement and oversight process that minimizes cronyism and favoritism5,6. Apart from these, robust scheme design and stakeholders incentives are also essential for successful implementation of the scheme. The key to reinventing government is changing the incentives that drive market within the public sector7.

Given the critical importance of the scheme, the specific objective of this study was to examine the scheme design and the incentive structure under RSBY and its implications for delivering health services to the intended beneficiaries.

Material & Methods

The study was a mixed method study and conducted in the districts of Patiala and Yamunanagar in the States of Punjab and Haryana, respectively, from 2011 to 2013. These two districts were chosen based on the following considerations: (i) RSBY had greater than two years of implementation in these districts at the start of the study; (ii) buy-in from various stakeholders of the scheme was there to support the implementation of the study; (iii) RSBY had a different set of partners involved these districts; and (iv) choosing one district each from two different States would capture variations in elements relating to capacity, governance, regulation, etc. across States. Review of key documents, stakeholder's in-depth interviews and exit interviews (for quantitative assessment) were used to examine the scheme design and the incentive structure. Secondary data analysis of the beneficiary enrolment and hospital empanelment and insurance claim by providers’ database was conducted.

Ethical clearances were obtained from the Ethics Committee at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK and the Institutional Ethics Committee at the Public Health Foundation of India, New Delhi.

Key documents were identified based on inputs from experts and included contractual agreements between various stakeholders, programmatic reports, policy documents and evaluation reports. These documents were retrieved from RSBY and MoLE website, Government offices including State Nodal Agencies (SNAs) of the studied States and personal communication with the Central-level policy makers. These were systematically reviewed and relevant data were extracted.

Twenty in-depth interviews of key stakeholders of the RSBY were conducted comprising policy makers, State representatives, representatives from insurance companies, representatives from third party administrators and public and private providers. A semi-structured in-depth interview guide (for key stakeholder interview) was developed and piloted. Interviews were conducted in a mix of languages (English, Hindi and Punjabi) which were later transcribed to English. Permission was sought to audio record the interviews. Thematic analysis was conducted for the in-depth interviews8.

Exit interviews of the patients from the selected RSBY empaneled hospitals were conducted. Beneficiary questions during the exit interviews included patient profile, hospital experience, out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures, etc. For the current study, OOP expenditure data from the exit interviews were used and analyzed. The 12 selected empanelled hospitals comprised three public and three private facilities in each of the two chosen districts. Consecutive samples were collected till the estimated sample size of 376 each for RSBY and non-RSBY beneficiaries was reached. For assessment of enrolment of beneficiaries and hospital empanelment, a secondary database of the BPL population was used, and lists of health facilities and RSBY-empanelled facilities in the districts were analyzed. These databases were obtained from the SNAs and district medical officers of both the States.

Descriptive analysis was done for enrolment and empanelment data, and bivariate analysis was conducted for OOP expenditures. Appropriate tests of significance (Student's t test) was used for OOP analysis. All statistical analyses were performed with STATA Version 9.0 (https://www.stata.com/).

Results

Gaps in scheme design were identified and categorized into the following five major categories - allocation of roles and responsibilities; enrolment of beneficiaries; empanelment of facilities; monitoring and supervision, and package rates.

Allocation of roles and responsibilities: The scheme was designed by the Central Government and was presented to the State Governments for implementation with flexibility to make changes to suit the local context. Some of the implementation responsibilities were with Central Government, some with the State Government and considerable with insurance companies (Table I). There were some overlaps in roles and responsibilities among them.

Table I.

Roles and responsibilities of Central and State Governments, insurance companies and third-party administrators (TPA) as specified in scheme design and contracts

| Roles & responsibilities | Central Government | State Government | Insurer/TPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oversight of scheme | Yes | Yes | |

| Financing | Yes | Yes | |

| Setting parameters (benefits package, empanelment criteria, etc.) | Yes | ||

| Hardware specifications (IT systems, smart card, etc.) | Yes | ||

| Accreditation/empanelment of providers | Yes | ||

| Collecting registration fees | Yes | ||

| Enrolment | Yes | Yes | |

| Setting rate schedules for services/reimbursement rates | Yes | ||

| Claims processing and payment | Yes | ||

| IEC, outreach, marketing to beneficiaries | Yes | ||

| Monitoring and supervision | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Training | Yes | Yes | Yes |

IEC, information, education and communication; IT, information and technology

Enrolment of beneficiaries: Two aspects regarding enrolment of beneficiaries were noted - first, the BPL families had to enroll every year and second, the contracts between State and the insurance firms had been stipulated to last only for a single year. The newly awarded contract to the firm began with the process of re-enrolling beneficiaries and had to undertake all administrative processes to implement the scheme for the contracted period.

Key stakeholders stated that the yearly enrolment required significant human and financial resources and was burdensome and redundant because BPL listings did not change yearly. In addition, the annual coverage cycle was interrupted every year since it took three months to reissue the insurance smart cards and this process was more challenging when the insurance contract was given to different companies in successive years.

The contract design allocated responsibility for awareness generation, and information, education and communication (IEC) to the insurance companies, both at the time of enrolment and thereafter. It was not in the interest of the insurance companies to do so since greater awareness could generate more demand for healthcare, resulting in an increase in both the number of claims and the claimed amount.

Empanelment of health facilities: The healthcare providers empanelled in the RSBY were not certified by any authority for the quality of care provided by them. Empanelment criteria, which were defined in the contract document between the State and the insurance company, were such that it was difficult for providers in rural areas to get empanelled in the scheme. The empaneled public hospitals were found to be more equitably distributed throughout the district as compared to private facilities, which were geographically clustered around pockets of population at the sub-district level. In Patiala, of a total of 115 potential facilities, 17 were empanelled and in Yamunanagar, 37 of 123 were empanelled.

Monitoring and supervision: The monitoring and supervision strategy was not clearly stated in the contract document, and the monitoring mechanisms and parameters were not well defined, including indicators of quality of care. There was also no mention of resources for monitoring and supervision at district level. At the Central Government level, a technical cell was engaged in overall scheme monitoring and supervision including data handling and management. At State level, monitoring and supervision was left to the insurance companies which sometimes led to the use of inadequately qualified staff. Some clear breaches of contractual terms (Table II) were found which were evident of weak monitoring and lack of attention to contract requirements.

Table II.

Examples of breach of contract

| • Lack of information dissemination to the beneficiaries: About packages covered and location of hospitals |

| • Delayed reimbursement by the insurance company of the amount claimed by providers |

| • Non-payment of transportation cost, to which beneficiaries were entitled by the providers |

| • No provision of food to the beneficiaries in the hospitals although this was part of the package |

| • Both public and private providers were not sharing information regarding the cost of treatment or money remaining in the smart card or information on pre- and post-hospitalization benefits |

| • Leakage of the scheme to non-eligible families: 15% of exit interview participants enrolled under the scheme were non-BPL. |

BPL, below the poverty line

OOP expenditure was analyzed from the exit interviews. A total of 751 exit interviews of RSBY (387) and non-RSBY (364) participants from selected 12 empanelled hospitals were conducted, and 399 participants were interviewed in Patiala district and 352 in Yamunanagar district. Data of five participants were not available, hence not included in the analysis. It was found that RSBY beneficiaries had incurred OOP expenditure of ₹5748 though it was lesser than for non-RSBY (₹10667) and less at public facilities when compared to private (Table III).

Table III.

Total out-of-pocket expenditure (in ₹) by participants

| District | n | Mean±SD | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patiala | 397 | 7559.9±14626.9 | 0.23 |

| Yamunanagar | 349 | 8747.5±12642.5 | |

| Patiala | |||

| Private | 201 | 9909.4±16209.6 | <0.01 |

| Public | 196 | 5150.5±12388.1 | |

| Yamunanagar | |||

| Private | 192 | 11927.1±15810.6 | <0.01 |

| Public | 157 | 4859.0±4778.2 | |

| Both districts | |||

| Private | 393 | 10895.1±16027.3 | <0.01 |

| Public | 353 | 5020.9±9754.8 | |

| Patiala | |||

| RSBY | 196 | 3760.1±11280.5 | <0.01 |

| Non-RSBY | 201 | 11265.2±16480.3 | |

| Yamunanagar | |||

| RSBY | 191 | 7788.2±5788.3 | 0.12 |

| Non-RSBY | 158 | 9907.0±17642.6 | |

| Both districts | |||

| RSBY | 387 | 5748.1±9211.0 | <0.01 |

| Non-RSBY | 359 | 10667.5±16990.9 |

RSBY, Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna; SD, standard deviation

Package rates: Under RSBY, there is a fixed capitation for every treatment in a package of care. The rates of the packages were predetermined by the Central Government, subject to time-to-time revisions. The private providers felt that package rates were not realistic and were set far too low; and it was unviable to have the same package rates across the entire country.

Incentive structures: The scheme was designed as a business model for a social sector scheme with incentives built-in for each stakeholder. Incentives varied across stakeholders and for some, the incentives were monetary and for others in enhanced reputation and recognition.

For the Central Government, financial contribution towards the payment of premiums to provide health insurance for beneficiaries gave it a role in various aspects of implementation, which would normally fall outside the Central Government mandate as health being a State subject in the Indian Constitution. The two State Governments (Punjab and Haryana) covered their poorest of the poor population with health insurance providing social security to the BPL population in the State. There were, however, no incentives for public staff, either at the Central or State Government levels, to take on the additional activities of RSBY.

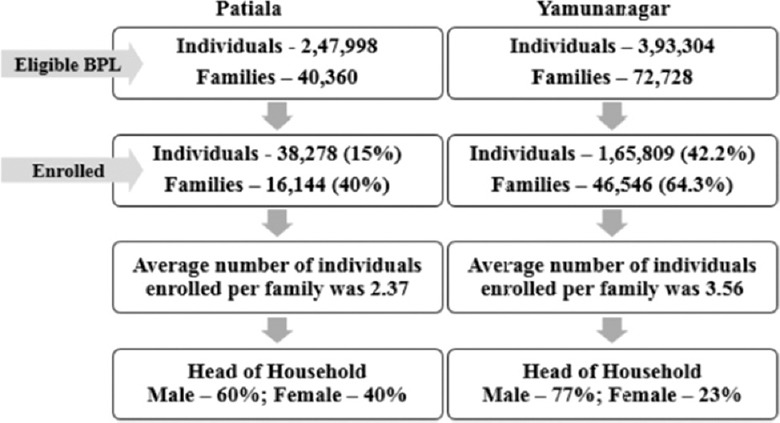

Insurance companies looked at RSBY as an opportunity to penetrate a segment of the population which was previously not within their reach. Since the premium was a fixed amount per household, insurance companies had an incentive to enrol a large number of households but restrict the number of household members enrolled per family as was evident from the secondary data analysis which showed low average number of beneficiaries (2.4 in Patiala and 3.6 in Yamunanagar) per family enrolled (maximum permissible being five) (Figure).

Figure.

Enrolment under Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna scheme (Patiala and Yamunanagar).

The incentive for a private healthcare provider was increased profit resulting from providing treatment to an increased number of beneficiaries, as payment was made on a fixed package rate depending on the number of beneficiaries treated. The public health providers saw RBSY as an opportunity to raise funds that could be utilized to enhance services in public hospitals.

Discussion

RSBY scheme was designed by the Central Government and presented to the State Governments for implementation. This study and others have found the process of enrollment of beneficiaries to be inefficient and leading to lack of coverage for the beneficiaries at the beginning of the contract period9,10. A standard approach in principal agent theory is to offer a schedule of price and quantity (or even quality) to which the agent responds11. However, in RSBY, price was the only contractual arrangement with providers and quantified targets were not observed. Furthermore, the prices stated for procedures in RSBY made no mention of quality.

Looking at the low coverage of the BPL population in both the States under the scheme, misalignment of incentives might be a plausible reason, where insurance companies were not making effort to enrol larger families or include the maximum number of family members allowed. The average family size enrolled was 2.4 in Patiala and 3.6 in Yamunanagar. Similar findings regarding enrolment under RSBY have been reported by other studies as well12,13,14. The low number of empaneled hospitals under the scheme (17 in Patiala and 37 in Yamunanagar) could have been done by insurance companies to minimize the claims and increase their profitability. It needs to be kept in mind that reasons for low coverage could also be family concern regarding the maximum claim limit. A lower number of empanelled hospitals could also be due to poor understanding of empanelment guidelines by the doctors or hospital administrative heads as was the case in Chhattisgarh in a study done by the Council of Tribal and Rural Development15. Some studies suggested that enrolment could have been better if some of the activities were delegated to the Panchayats such as provision of suitable place for registration, crowd management, standby arrangement in case of power failure, late delivery of smart cards, etc16. Findings of the current study were consistent with the other evaluations of RSBY17.

Results from the study showed that effective oversight was conspicuously lacking, especially during the process of enrolment of beneficiaries, empanelment of health facilities, awareness building and implementation. Most of the activities were undertaken primarily by the insurance company although their stimulus may have been misaligned or even in conflict with State goals. Monitoring and supervision is one of the main pillars of any programme for efficiency and effectiveness. However, monitoring and supervision under the RSBY scheme was weak. At the start of health insurance scheme, there is always a risk of low compliance18. This is why, monitoring and supervision becomes indispensable. In RSBY, several breach of contracts were observed, without any action.

With regard to weak health systems and poor healthcare coverage, RSBY was seen as a landmark scheme which contributed significantly to the design of AB, specifically Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY)19. RSBY provided insurance coverage of ₹30,000 for up to five members of a family per annum, for a target beneficiary base of 60 million families19. The target beneficiary in PMJAY has increased to 107.4 million families and estimated 535 million people, equivalent to about 40 per cent of Indian population with insurance coverage of ₹ five lakhs per family per year. The financial coverage in PMJAY is around 17 times more generous than RSBY19. Both the schemes primarily focus on in-patient care. Outpatient care remains unaddressed. Although the number of packages has increased from 1090 in RSBY to 1393 in PMJAY20,21, States are not availing the flexibility to adapt standard rates of the packages to the local context. The cost of medicines and diagnostics in OPD are the major contributors to OOP expenditures, which were neither covered in RSBY nor in PMJAY19,22,23. The impact of health insurance on reduction of OOP expenditure is not always consistent24. In the present study, OOP expenditure was more pronounced in Yamunanagar when compared to Patiala. A possible reason could be increased empanelment of the public-sector facilities which could have contributed to reduction in OOP expenditure.

Results of our study need to be cautiously interpreted and generalized as there were certain limitations in the study. For example, study participants were identified from selected hospitals, though ideally both RSBY and non-RSBY beneficiaries should have been identified through household surveys. Qualitative methods (focus group discussions or interviews) to obtain in-depth perceptions of the beneficiaries would have better reflected the gaps in the scheme design. Facilities were selected based on patient load in both the districts, due to logistical constraints.

Strength of RSBY lies in the fact that it is a social welfare scheme with inbuilt incentives for various stakeholders to motivate them to provide hospitalization coverage to the poor. The fact that private service providers have participated in RSBY is evident of its being a successful business model for them. However, gaps in design identified in the study in terms of poor enrolment practices, low enrolment rate, distribution of roles and responsibilities, clustering of empanelled facilities, fixed package rates, weak monitoring and supervision, incurring OOP expenditure despite the scheme being cashless were useful lessons learnt. Some of these gaps have been addressed in PMJAY. For such schemes to achieve their objectives, State Governments have to be more accountable for scheme implementation.

Acknowledgment:

Authors thank Dr Anne Mills from London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK, for her supervision, guidance and support on the research.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Capacity Strengthening Strategic Award to the Public Health Foundation of India and a consortium of UK universities.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojna. PM-JAY - Ayushman Bharat. National health agency. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2018. [accessed on October 15, 2018]. Available from: https://www.pmjay.gov.in/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Initiatives of ministry of labour & employment during last one year. New Delhi: Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India; 2008. May 22, [accessed on October 15, 2018]. Press Information Bureau. Available from: http://www.pib.nic.in/newsite/erelcontent.aspx?relid=39058 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Labour & Employment (MoLE). Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) Operational Manual. New Delhi: MoLE, Government of India; 2014. [accessed on October 15, 2018]. Available from: http://www.rsby.gov.in/Docs/Revamp_of_RSBY_Phase_I_Operational_Manual(Released_%2012th_%20June_%202014).pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gentry B, Fernandez L. Paris: OECD; 1998. Evolving public-private partnerships: General themes and examples from the urban water sector. Globalization and the environment: Perspectives from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and dynamic non-member economies; pp. 99–125. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batley R, Scott Z. Global event working paper. New York: United Nations Development Programme; 2010. Capacities for local service delivery: The policy link; p. 1314. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kula N, Fryatt RJ. Public-private interactions on health in South Africa: Opportunities for scaling up. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29:560–9. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osborne A, Gaebler T. MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company Inc.; 1992. Market-oriented government: leveraging change through the market: Reinventing government: how the entrepreneur spirit is transforming the public sector. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Q Res Psychol. 2016;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Das A. Social health insurance for poor in Odisha: A study of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana. In: Kunhikannan TP, Breman J, editors. The long road to social security: Assessing the implementation of national social security initiatives for the working poor in India. Vol. 11. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 439–66. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kannan KP, Varinder J. National health insurance initiative for the poor. In: Kunhikannan TP, Breman J, editors. The long road to social security: Assessing the implementation of national social security initiatives for the working poor in India. Vol. 2. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biglaiser G, Ma A. Regulating a dominant firm: Unknown Demand and industry structure. Rand J Econ. 1995;26:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nandi A, Ashok A, Laxminarayan R. The socioeconomic and institutional determinants of participation in India's health insurance scheme for the poor. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dror DM, Vellakkal S. Is RSBY India's platform to implementing universal hospital insurance? Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:56–63. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.93425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karan A, Yip W, Mahal A. Extending health insurance to the poor in India: An impact evaluation of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana on out of pocket spending for healthcare. Soc Sci Med. 2017;181:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centre for Tribal and Rural Development. Independent assessment study on process of enrolment under Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana and Mukhyamantri Swasthya Bima Yojana in Chhattisgarh. 2013. [accessed on July 31, 2018]. Available from: http://www.cg.nic.in/healthrsby/RSBY_Documents/Revised%20FINAL%20REPORT%20on%20RSBY%20Enrollment%20%2029-06-2013.pdf .

- 16.Kunhikannan TP, Aravindan KP. Functioning of contingent social security schemes in Kerala: The social and institutional context of delivery at the local level. In: Kunhikannan TP, Breman J, editors. The long road to social security: Assessing the implementation of national social security initiatives for the working poor in India. Vol. 2. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 207–46. [Google Scholar]

- 17.New Delhi: GIZ and Prognosis; 2012. German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ). Evaluation of implementation process of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana in select districts of Bihar, Uttarakhand and Karnataka. Indo German Social Security Programme. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carrin G. Social health insurance in developing countries: A continuing challenge. Int Soc Secur Rev. 2002;55:57–69. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lahariya C. ’Ayushman Bharat’ program and universal health coverage in India. Indian Pediatr. 2018;55:495–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rastriya Swasthya Bima Yojna. Medical and surgical package rates. New Delhi: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India; 2013. [accessed on October 15, 2018]. Available from: http://www.rsby.gov.in/Documents.aspx?id=4 . [Google Scholar]

- 21.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2018. [accessed on February 12, 2019]. Press Information Bureau. Cashless Facility under PMJAY. Available from: http://www.pib.nic.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1564018 . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghosh S, Gupta ND. Targeting and effects of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana on access to care and financial protection. Econ Pol Wkly. 2017;52:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sood N, Bendavid E, Mukherji A, Wagner Z, Nagpal S, Mullen P. Government health insurance for people below poverty line in India: Quasi-experimental evaluation of insurance and health outcomes. BMJ. 2014;349:g5114. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acharya A, Vellakkal S, Taylor F, Masset E, Satija A, Burke M, et al. Impact of national health insurance for the poor and the informal sector in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. London: Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPICentre) London: Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London; 2012. p. 110. [Google Scholar]