Abstract

A recent study shows that the commensal fungus Candida albicans is an inducer of differentiation of human CD4+ Th17 cells harboring heterologous specificity for other fungi. Th17 cells that are cross-reactive to Aspergillus fumigatus antigens can drive exaggerated airway inflammation in humans, thus revealing insights into the evolutionary benefits of C. albicans as a commensal microbe.

Studies of antifungal immunity lag behind those of other microbial pathogens, and there are no vaccines to any pathogenic fungi. Candida albicans (Ca) is a pathobiont that widely colonizes human mucosae, including the intestine. Its ubiquitous presence suggests evolutionary pressure for symbiosis. Nonetheless, opportunistic candidiasis arises as a result of T cell immune compromise. Although most notable in HIV/AIDS, this compromise also occurs in settings where Th17 cells or IL-17 signaling are impaired (1). Th17 responses mediate defense against fungal infections, especially Ca, but these protective responses may cause autoinflammatory disorders -- not only in the intestine, but also in the lung and other tissues.

Organ-specific autoinflammatory disorders can be caused by inappropriate responses to the microbiome, mediated by reactivation of intestinally-generated Th17 cells. In mice, this principle was elegantly illustrated in studies of intestinal CD4+ Th17 cells reactive to segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB). Cross-reactive T cells induced by SFB caused inflammation in non-intestinal tissues (2–4). However, the analogous microbial inducer of systemic Th17 inflammation in humans is unknown, nor do we understand the extent to which microbial cross-reactive T cells have pathogenic potential.

A new report by the Scheffold group (5) demonstrates the capability of Ca-reactive human Th17 cells to cross-react to an unrelated fungus, Aspergillus fumigatus (Af), and hence exacerbate acute pulmonary inflammation. In this study, Bacher et al. identified fungus-reactive CD4+ T cells by stimulating peripheral blood mononuclear cells with lysates from 30 fungal species of the human mycobiome. Of these, Ca was by far, the dominant inducer of IL-17 production, reflecting a surprisingly selective capability of Ca to induce strong Th17 responses in humans.

Re-stimulation of Th17 cells in culture with either Ca or Af lysates revealed a remarkable high incidence of cross-reactive T cells, confirmed at a single-cell level, with dually-reactive T cell clones responding to both fungi; however, clones that were specific to Af, didnot generally respond to Ca. To explore the origins of these fungal-reactive T cells, the authors showed that Af-reactive T cells from the “memory” but not the “naïve” T cell compartments, exhibited Ca cross-reactivity. However, cross-reactivity was not restricted to the memory pool when Af-reactive T cells were re-stimulated with lysates from other Aspergillus species. Thus, there appears to be a significant proportion of Ca-cross-reactive T cells in the Af-reactive memory pool that expands upon prior Ca exposure in healthy individuals. Functionally, cross-reactive cells were not identical to those with more limited reactivity, as evidenced from distinct cytokine expression profiles. Moreover, Af-cross reactive cells were not enriched among the Ca-reactive IL-17+ clones. In addition, depletion of Ca-reactive cells from the T cell pool reduced IL-17 production following stimulation with Af antigens in vitro. These data indicated that Ca, as an intestinal commensal fungus, could dominantly influence the human anti-fungal Th17 response to heterologous fungi (5).

To identify fungal-specific T cell antigens, the authors screened reactivity of T cells to a panel of C. albicans proteins. The mannose protein Mp65 elicited strong IL-17 responses, which were more potent in Ca-reactive T cells than in ‘Af-only’ reactive cells. Of note, the Af cell wall glucanase 4 (Scw4) is ~45% homologous to Mp65 and elicited similar, albeit modest, responses. Hence, Mp65 and Scw4 provide, at least in part, a mechanistic explanation for antigenic cross-reactivity (5). Presumably, there are additional cross-reactive epitopes, and their identification represents an important area of future inquiry. In this regard, a C. albicans vaccine was based on the agglutinin-like sequence 3 (Als3)Ca epitope, and is currently being tested in clinical trials for vulvovaginal candidiasis (6). Moreover, Als3 is cross-reactive with Staphylococcus aureus antigens (7), highlighting another instance of cross-reactive immunity between highly-distinct organisms.

To determine if cross-reactive antifungal Th17 cells modulated responses at extraintestinal sites, the authors characterized Af-reactive T cells in patients with lung pathology known to be driven by IL-17. Specifically, n asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, selective expansion of Af-reactive Th17 cells ( but not of Th1 cells), was observed (5). Additionally, elevated Af-reactive IL-17+ cells were seen in lung samples from cystic fibrosis patients, where aspergillosis constitutes a significant clinical threat. However, these cells were not detected in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, consistent with the fact that they did not characteristically exhibit elevated Af colonization relative to the normal population. In patients with Af-driven acute allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), there were increased concentrations of IL-4 and IgE, as well as increased numbers of Af-reactive IL-17+ cells relative to healthy controls. IL-17 concentrations declined after broad-spectrum antifungal therapy, an event that was associated with good prognosis, but did not impact IL-4, IFNγ, IL-10 or IL-2. However, positive outcomes were not observed when patients were treated with Itraconazol, which selectively targets Aspergillus, but not Candida (5).Thus, targeting Ca might be an unexpected clinical target for treating ABPA.

IL-17 is tonically expressed in the intestine, where it mediates epithelial repair to maintain homeostasis and prevent dysbiosis (8). Crohn’s disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel complex disorder of unknown etiology; however, GWAS studies have implicated antifungal response genes in its pathogenesis -- perhaps acting as a fungal trigger (9). Indeed, Bacher and colleagues measured increased frequencies of Ca- and Af-reactive cross-reactive Th17 cells in the of CD patients compared with controls. Since Ca and Af are generally not found in overlapping anatomical compartments (intestine/mouth/skin/vaginal tract versus lung), these findings indicate that heterologous immunity can be induced upon expansion of cross-reactive Th17 cells which can then act within distinct tissues (5). Whereas biologic drugs targeting IL-23 can be beneficial in CD (presumably upstream of Th17 cell activation), anti-IL-17 therapy has been unexpectedly harmful, halting various trials (10). Follow up studies revealed that IL-17-driven epithelial repair appears to outweigh its pathologic potential in models of murine colitis, perhaps indicating that Ca-specific Th17 cells -- and hence Candida commensalism -- have been evolutionarily selected to maintain homeostasis in the intestine.

Another demonstration that colonization by pathobiont fungi can exert protective host benefits was shown in mice in a contemporaneous paper by Shao et al. (11). Ca is not a normal commensal microbe in mice. However, Establishment of systemic Th17 immunity by inducing commensal Ca colonization in mice conferred a marked reduction in susceptibility to invasive infection by Ca and other extracellular pathogens (including S. aureus) relative to mice with Ca; however Ca colonization also promoted pathological Th17-mediated airway inflammation in mice, similar to the Bacher et al. findings in humans.

Notably, both studies showed that systemic expansion of fungal-specific Th17 cells and other immune modulatory effects of commensal Ca colonization could be overturned following antifungal therapy (5, 11); this suggested that persistent antigen exposure might be required to sustain the expansion of Ca-specific CD4+ T cells. Even though these Th17 cells express “memory” immune cell markers (CD154 in humans, CD44 in mice), they are quite ‘forgetful’ in the sense that they do not persist without continuous stimulation. It is possible that this need for tonic stimulation by fungal pathobionts can explain -at least in part -- the evolutionary pressure to maintain commensalism.

This work reveals newfound facets of the symbiosis between Ca and humans, including dominant protective roles against invasive Ca infection and heterologous immunity to other pathogenic organisms. However, this can also result in Th17-driven immunopathology. Thus, these principles may lay groundwork for strategies to fine-tune systemic Th17 immunity with fungal probiotics or targeted antifungal agents in settings where IL-17 can be harmful.

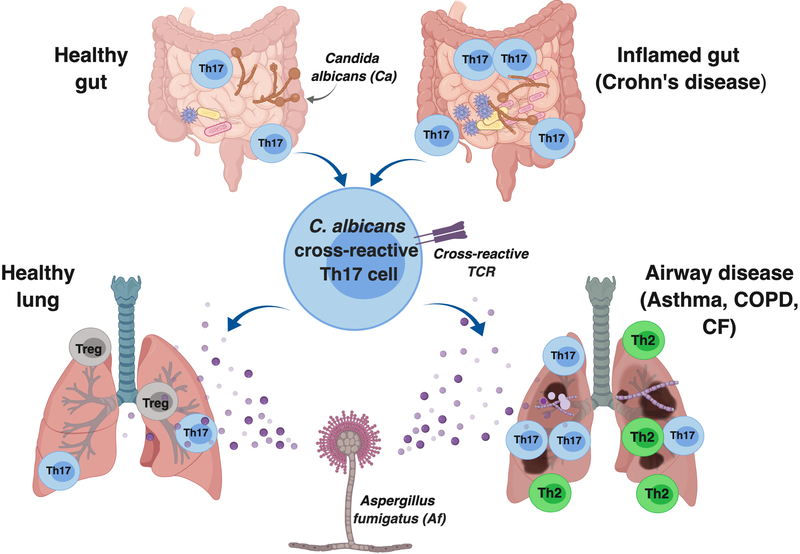

Figure 1. Gut Candida albicans Can Drive Heterologous Expansion of Cross-Reactive Th17 Cells During Acute Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis.

C. albicans exists as a commensal in the healthy human gut and its continuous presence maintains homeostatic Candida-specific Th17 cells. Dysbiosis during inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn’s disease can promote expansion of C. albicans specific “memory Th17 cells”. Many of these cells cross-react with A. fumigatus antigens, promoting exaggerated effector Th17 responses during airway inflammatory diseases, thus causing increased pathology.

Acknowledgments

SLG was supported by NIH grant DE022550. There are no conflicts of interest. SSW. is supported by the HHMI Faculty Scholar’s program, NIH Director’s Pioneer Award program (DP1-AI131080), and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigator in the Pathogenesis Award

References

- 1.Conti HR, and Gaffen SL. 2015. IL-17-Mediated Immunity to the Opportunistic Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans. J Immunol 195: 780–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley CP, Teng F, Felix KM, Sano T, Naskar D, Block KE, Huang H, Knox KS, Littman DR, and Wu HJ. 2017. Segmented Filamentous Bacteria Provoke Lung Autoimmunity by Inducing Gut-Lung Axis Th17 Cells Expressing Dual TCRs. Cell Host Microbe 22: 697–704 e694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee YK, Menezes JS, Umesaki Y, and Mazmanian SK. 2011. Proinflammatory T cell responses to gut microbiota promote experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 Suppl 1: 4615–4622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Y, Torchinsky MB, Gobert M, Xiong H, Xu M, Linehan JL, Alonzo F, Ng C, Chen A, Lin X, Sczesnak A, Liao JJ, Torres VJ, Jenkins MK, Lafaille JJ, and Littman DR. 2014. Focused specificity of intestinal TH17 cells towards commensal bacterial antigens. Nature 510: 152–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bacher P, Hohnstein T, Beerbaum E, Rocker M, Blango MG, Kaufmann S, Rohmel J, Eschenhagen P, Grehn C, Seidel K, Rickerts V, Lozza L, Stervbo U, Nienen M, Babel N, Milleck J, Assenmacher M, Cornely OA, Ziegler M, Wisplinghoff H, Heine G, Worm M, Siegmund B, Maul J, Creutz P, Tabeling C, Ruwwe-Glosenkamp C, Sander LE, Knosalla C, Brunke S, Hube B, Kniemeyer O, Brakhage AA, Schwarz C, and Scheffold A. 2019. Human Anti-fungal Th17 Immunity and Pathology Rely on Cross-Reactivity against Candida albicans. Cell 176: 1340–1355 e1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibrahim AS, Luo G, Gebremariam T, Lee H, Schmidt CS, Hennessey JP Jr., French SW, Yeaman MR, Filler SG, and Edwards JE Jr. 2013. NDV-3 protects mice from vulvovaginal candidiasis through T- and B-cell immune response. Vaccine 31: 5549–5556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spellberg B, Ibrahim AS, Yeaman MR, Lin L, Fu Y, Avanesian V, Bayer AS, Filler SG, Lipke P, Otoo H, and Edwards JE Jr. 2008. The antifungal vaccine derived from the recombinant N terminus of Als3p protects mice against the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun 76: 4574–4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whibley N, and Gaffen SL. 2015. Gut-Busters: IL-17 Ain’t Afraid of No IL-23. Immunity 43: 620–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iliev ID, Funari VA, Taylor KD, Nguyen Q, Reyes CN, Strom SP, Brown J, Becker CA, Fleshner PR, Dubinsky M, Rotter JI, Wang HL, McGovern DP, Brown GD, and Underhill DM. 2012. Interactions between commensal fungi and the C-type lectin receptor Dectin-1 influence colitis. Science 336: 1314–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hueber W, Sands BE, Lewitzky S, Vandemeulebroecke M, Reinisch W, Higgins PD, Wehkamp J, Feagan BG, Yao MD, Karczewski M, Karczewski J, Pezous N, Bek S, Bruin G, Mellgard B, Berger C, Londei M, Bertolino AP, Tougas G, Travis SP, and Secukinumab G in Crohn’s Disease Study. 2012. Secukinumab, a human anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody, for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: unexpected results of a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut 61: 1693–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shao TY, Ang WXG, Jiang TT, Huang FS, Andersen H, Kinder JM, Pham G, Burg AR, Ruff B, Gonzalez T, Khurana Hershey GK, Haslam DB, and Way SS. 2019. Commensal Candida albicans Positively Calibrates Systemic Th17 Immunological Responses. Cell Host Microbe 25: 404–417 e406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]