Short abstract

Ethanol promotes KLF4 and M2 phenotype while acetaldehyde attenuates KLF4 and promotes M1 macrophage, supporting the increased presence of both M1 and M2 macrophage populations in alcoholic liver disease.

Keywords: ethanol metabolism, KLF4

Abstract

Macrophages play an important role in inflammation and liver injury. In ALD, activated macrophages, including M1 (proinflammatory) and M2 (anti‐inflammatory) macrophages, are present in the liver. As KLF4 has been described as a regulator of macrophage polarization, we investigated its role in ALD. Chronic alcohol feeding in C57Bl/6 mice led to increased expression of M1 (TNF‐α, MCP1, and IL‐1β) and M2 (Arg1, Mrc1, and IL‐10) genes and the frequency of CD206+CD163+ M2 macrophages in the liver. KLF4 mRNA and protein levels were increased in the livers of EtFed compared with PF mice. In macrophages, in vivo and in vitro, EtOH increased KLF4 levels, transcriptional activity, and expression of M1 and M2 genes. KLF4 knockdown and overexpression experiments demonstrated alcohol‐dependent and ‐independent functions of KLF4 in regulating M1 and M2 markers. KLF4 siRNA treatment, alone and in synergy with alcohol, increased the levels of M1 markers. In contrast, KLF4 overexpression increased the levels of M2 and decreased M1 markers, and this was enhanced further by alcohol. KLF4 was regulated by alcohol and its metabolites. KLF4 mRNA and activity were increased in the presence of 4‐MP, an inhibitor of ADH, and CYP2E1. However, inhibition of acetaldehyde breakdown attenuated KLF4 induction and promoted M1 polarization. We conclude that KLF4 regulates M1 and M2 markers in ALD. EtOH promotes KLF4 and M2 phenotype, whereas acetaldehyde attenuates KLF4 and promotes M1 macrophage, which may explain the increased presence of M1 and M2 macrophage populations in ALD.

Abbreviations

- 4‐MP

4‐methylpyrazole

- ADH

alcohol dehydrogenase

- ALD

alcoholic liver disease

- ALDH

aldehyde dehydrogenase

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- APC

allophycocyanin

- Arg

arginase, CYP2E1 cytochrome P450 2E1

- EtFed

ethanol fed

- EtOH

ethanol

- KC

Kupffer cell

- KLF4

Krüppel‐like factor 4

- LMNC

liver mononuclear cell

- MRC1

mannose receptor, C type 1

- PF

pair fed

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor

- qRT‐PCR

quantitative real‐time PCR

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

Introduction

ALD is a significant burden on human health, and it affects >10 million people in the United States and accounts for ∼3.8% of global mortality [1, 2–3]. ALD includes a spectrum of disease conditions, ranging from steatosis and cirrhosis to liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma [4]. Liver injury, which results from alcohol, is mediated through alcohol metabolites; reactive oxygen/nitrogen species; proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF‐α; increased endotoxin via gut permeability; and other endogenous mediators [5, 6]. One of the central components in the development of ALD is the activation of liver‐specific macrophages; KCs and recruitment of inflammatory cells and macrophages to the liver [7, 8].

Macrophages exhibit great plasticity in the presence of external stimuli, and alcohol acts as one of such external factors [7, 9]. During ALD, the liver is populated by M1 and M2 macrophages [7, 10]. In humans, the liver sinusoids are rich in M2 macrophages expressing CD163 and CD206 during ALD [10, 11]. Macrophages can exist in a continuum of polarization states, and the 2 distinct phenotypes of macrophages, which are extremes of this continuum, are M1 and M2 [9, 12, 13]. LPS and IFN‐γ promote macrophage differentiation to a “classical” M1 phenotype. M1 macrophages are characterized by the expression of high levels of proinflammatory cytokines, high production of reactive nitrogen and oxygen intermediates, and promotion of a Th1 response, with strong antimicrobial and anti‐tumor activity. IL‐4 and IL‐13 are M2‐polarizing agents that generate “alternatively activated” M2 macrophages, which are characterized by efficient phagocytic activity, with increased expression of mannose and galactose receptors switching on the Arg pathway to produce ornithine and polyamines and increased anti‐inflammatory cytokine production [12, 14]. M2 macrophages are involved in promotion of tissue remodeling and tumor progression and have immunoregulatory functions.

The characterization of M1 and M2 macrophages provides important tools for understanding the regulation of inflammatory processes during alcohol‐induced liver injury. The promotion of M2 KC polarization has been shown to be protective at the early stages of ALD, as it promotes M1 KC apoptosis and hepatocyte senescence [15, 16]. Thus, it is important to evaluate the molecular mechanisms that govern the M1/M2 polarization during ALD. Transcription factors play a major role in regulation of macrophage polarization. The M1 macrophage signals, IFN‐γ and LPS, control gene expression via transcription factors, including STAT1, JAK2, IFN regulatory factors, NF‐κB, and AP‐1 [14, 17]. The M2 stimulus IL‐4 leads to activation of STAT6, which activates transcription of target genes [12, 18]. Studies have also demonstrated the role of coactivators, such as PPARγ, PPARα, PPARγ coactivator 1β, and hypoxia‐inducible factor‐2α in regulating the M2 phenotype [19, 20, 21–22]. Recently, the role of KLF4 has been identified in macrophage regulation. KLF4, which is one of the 17‐member family of the mammalian transcription KLF is a zinc finger class of DNA‐binding transcriptional regulators [23, 24]. KLF4 was shown to induce M2 macrophage phenotype, whereas it reduced M1 macrophage expression [25]. Given the role of KLF4 in regulating macrophage M1 and M2 polarization, we hypothesized that KLF4 might be involved in alcohol‐induced macrophage polarization in ALD. Here, we present data that KLF4 is up‐regulated in macrophages exposed to alcohol and regulates the expression of M1 and M2 genes in an alcohol‐dependent and ‐independent manner. Results from our study suggest an important role of EtOH metabolism in regulating the expression of KLF4 in macrophages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal studies

All animals received proper care, in agreement with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Eight‐wk‐old C57Bl/6 female mice were used for the study. The animals on a chronic EtOH regime received 5% (v/v) EtOH (36% EtOH‐derived calories) containing a Lieber‐DeCarli diet (EtFed) or PF diet with an equal amount of calories, where the alcohol‐derived calories were substituted with dextrane‐maltose (Bio‐Serv, Frenchtown, NJ, USA) for 5 wk [26]. Serum was separated and frozen at −80°C. Livers were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, stored in RNAlater (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) for RNA extraction, or fixed in 10% neutral‐buffered formalin for histopathology.

KC isolation

Mice receiving an EtFed or PF diet received anesthesia with ketamine (100 mg/kg), and KCs were isolated as described previously [27]. In brief, the mouse livers were perfused with saline solution for 10 min. Then, it was followed by in vivo digestion with liberase enzyme for 5 min and in vitro digestion for 30 min. Percoll gradient was used to separate the nonhepatocyte content. The intercushion fraction was washed and adhered to plastic in DMEM with 5% FBS. The KCs adhered to the plastic, and the nonadherent fraction was washed off in DMEM with 10% FBS. Cells from 2 mice were pooled, given the limited number of KCs available from each animal for RNA isolation.

Histopathology

Liver sections were stained with H&E and analyzed by microscopy, as described [27].

Biochemical assays

Serum ALT was determined by use of a kinetic method (D‐Tek, Bensalem, PA, USA).

Flow cytometry assay

Isolated LMNCs were resuspended at a concentration of ∼106 cells/50 μl in FACS staining buffer containing anti‐mouse CD16/CD32 mAb (2.4G2) from BD PharMingen (San Jose, CA, USA) to block nonspecific binding to FcγRs and incubated for 10 min at 4°C. Cells were stained with Live/Dead Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain Kit from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA) to gate out dead cells. LMNCs were immunostained with CD45 APC‐Cy7, CD11b‐PE, and F4/80‐APC. CD45+ cells were gated, and the percentage of CD11b+ and F4/80+ was determined from the CD45+ population.

To determine the frequency of the M2 macrophage population, the LMNCs were stained with unconjugated CD163 antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). We stained the cells with CD11b‐FITC, F4/80 PerCP‐Cy5.5, and CD206‐Alexa 647 and incubated for 30 min in the dark at 4°C (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). For the negative control, the cells were stained with isotype‐matched control antibodies (BioLegend). The cells were washed and incubated with PE‐conjugated secondary antibody, specific for CD163, for another 25 min in the dark at 4°C. The cells were washed with FACS staining buffer and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. The cells were acquired on a BD LSR II instrument (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), and the data were analyzed by FlowJo software (Ashland, OR, USA).

Reagents

High‐glucose DMEM cell‐culture media, antibiotics, and nonessential amino acids were purchased from Gibco (Grand Island, NY, USA). LPS and IL‐4 were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) and PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), respectively. KLF4 siRNA and scrambled siRNA were from Life Technologies. KLF4 expression plasmid was procured from Qiagen. Inhibitor, 4‐MP, and cyanamide were purchased from Sigma. MG132 and PD98059 were purchased from Calbiochem (Billerica, MA, USA). NF‐κB SN50 cell‐permeable inhibitory peptide and NF‐κB SN50M cell‐permeable control peptide were obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY, USA). β‐Actin and KLF4 antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA).

Cell‐culture experiments with RAW 264.7 macrophages

RAW cells (1 × 105/well) were cultured in the presence of EtOH (50 mM) for different time‐points (0–48 h). M1 macrophages were generated by treating RAW cells with LPS (100 ng/ml), whereas IL‐4 (10 ng/ml)‐treated RAW cells were polarized to M2 macrophages for 16 h. RAW cells were also treated with different doses of EtOH (0–100 mM) for 48 h. For inhibitor experiments, RAW cells were pretreated with the inhibitors for 1 h before EtOH addition, and the cells were incubated for 48 h. The cells were harvested, and supernatants were collected for different assays.

PCR

RNA was extracted from the liver or RAW macrophages or KCs by use of the Zymo kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). OD (260/280 and 260/230 ratios) was measured to check RNA quality. cDNA was transcribed from l μg total RNA, by use of the iScript RT System (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), in a final volume of 20 μl. SYBR Green‐based qRT‐PCR was performed by use of the iCycler (Bio‐Rad). Eighteen seconds served as the endogenous control for the experiments. The level of the target gene expression was measured by ΔΔ comparative threshold values by use of the ratio of the fold change in target gene expression versus the fold change in reference gene expression (18 s).

Western blot

Tissue lysates and cell lysates were analyzed on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane overnight and then blocked for 2 h in blocking buffer containing TBS, 0.1% Tween 20, and 5% nonfat milk. Primary antibodies against mouse KLF4 and β‐actin (Abcam) were used overnight at 4°C in blocking buffer, followed by 3 washing steps. For detection, appropriate secondary HRP‐linked antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were used for 1 h in blocking buffer. The immunoreactive bands were detected by chemiluminescence by use of Clarity ECL Western substrate (Bio‐Rad) and LAS‐4000 infrared, Version 2.02 (Fujifilm Life Science, Stamford, CT, USA). The results were quantified by densitometric analysis by use of Multi Gauge, Version 3.2, image software (Fujifilm Life Science).

Alcohol measurement and ALDH assay

Alcohol levels in the RAW cell‐culture supernatant were measured by the Analox Alcohol analyzer (Analox Instruments, Lunenburg, MA, USA). ALDH levels were measured in the RAW cell lysates by the ALDH Activity Assay Kit from Abcam, following the manufacturer's instructions. ALDH activity was represented as nmol of NADH, generated per min/ml (nmol/min/ml), which was represented as mU/ml. One unit is the amount of enzyme that generates 1.0 μmol NADH/min at pH 8 at room temperature.

Transfection assays

RAW 264.7 mouse macrophages were cultured in high glucose containing DMEM, supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. All transient transfection and overexpression procedures were performed in the RAW264.7 cell line. For overexpression, RAW264.7 cells were infected with the empty control vector or the mouse KLF4 gene (pCMV6 vector). Transient transfection assays were performed with X‐tremeGENE DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Scrambled and KLF4 siRNA were transfected at the concentration of 50 nM with RNAiMAX reagent (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

KLF4 activation assay

KLF4 activation assay was performed by use of the GFP‐reporter assay kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). In brief, RAW 264.7 cells were transfected with Cignal GFP‐reporter plasmid or control plasmids (negative or positive) with X‐tremeGENE DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche Diagnostics). Twenty‐four hours after transfection, cells were treated with EtOH for different duration, as indicated in the figures. Cells were also cotransfected with KLF4 siRNA or KLF4 expression construct, as indicated in the figures. Cells were harvested, and the KLF4 activation was monitored via flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

All values expressed as mean ± sem were obtained from 3 or more independent experiments. Comparison between groups was made with the Student's t‐test and ANOVA test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

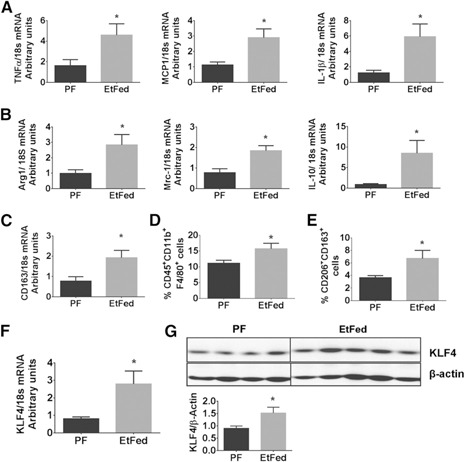

M1 and M2 macrophages are present in the liver after chronic alcohol feeding in mice

Chronic alcohol feeding in mice is characterized by inflammation, immune cell activation, cellular injury, and steatosis in the liver. The serum ALT levels were increased in the EtFed mice, indicating liver injury and steatosis was present on H&E staining of the liver compared with PF controls (Supplemental Fig. 1A and B). Livers from EtFed mice showed a 2‐ to 4‐fold increase in macrophage activation markers TNF‐α, MCP‐1, and IL‐1β compared with PF controls (Fig. 1A). We also observed a significant increase (2‐ to 8‐fold) in the expression of M2 genes (Arg1, Mrc1, and IL‐10; Fig. 1B). We also found an increase in the levels of CD163 mRNA (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Chronic alcohol feeding induced a mixed M1/M2 macrophage phenotype in vivo. C57Bl/6 female mice received Lieber‐DeCarli alcohol (EtFed) or PF diet for 5 wk. Liver samples and cells were collected from the mice. (A) mRNA expression of proinflammatory genes TNF‐α, MCP‐1, and IL‐1β was quantified by qRT‐PCR. (B) M2 macrophage markers; Arg1, Mrc1, and IL‐10 were quantified by qRT‐PCR. (C) CD163 mRNA levels were also evaluated by qRT‐PCR. (D) The percentage of CD45+CD11b+F4/80+ population in the LMNCs was assessed by flow cytometry. (E) Expression of F4/80+ macrophages expressing CD206 and CD163 in liver was determined by flow cytometry. (F) mRNA expression of KLF4 was determined by qRT‐PCR. (G) Western blot analysis shows the expression of KLF4 and β‐actin in the liver of EtFed and PF mice. The data are represented as mean ± sem, n = 6–8 mice/group. *P < 0.05.

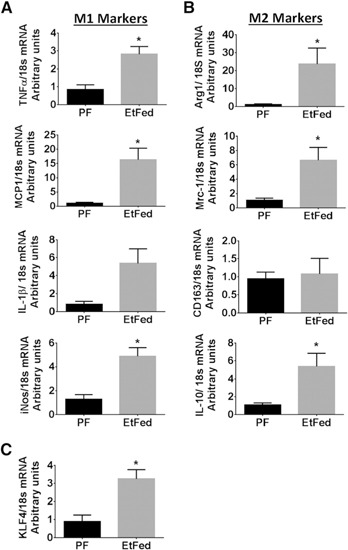

We evaluated further the levels of M1 and M2 markers in the KCs in vivo. We observed that TNF‐α, MCP‐1, and iNos were increased in EtFed mice compared with PF controls, indicating M1 polarization (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, there was a significant increase in the expression levels of Arg1, Mrc1, and IL‐10 in the KCs of the EtFed compared with PF mice, demonstrating M2‐type polarization (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Modulation of M1 and M2 markers and KLF4 expression with EtOH feeding. KCs isolated from PF or EtFed mice (5 wk of feeding) were pooled from 2 mice (n = 6/group), and total RNA was isolated and analyzed for (A and B) mRNA expression of M1 and M2 genes in the KCs and (C) mRNA levels of KLF4 by use of specific primers by qRT‐PCR. Values of relative mRNA expression normalized for housekeeping gene 18s are shown as mean ± sem. Statistically significant differences are shown (*P < 0.05 vs. PF control cells).

We performed flow cytometric analysis of the liver immune cell population and observed a significant increase in the frequency of CD45+CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages in the EtFed mice compared with PF controls (Fig. 1D). We observed further a 3‐fold increase in the frequency of CD163+CD206+ macrophages in the EtFed mice compared with PF controls (Fig. 1E).

KLF4 expression is increased in vivo in ALD in mice

KLF4 has been identified as a critical regulator of M2 macrophage polarization [25]. As we observed a significant increase in M2 gene expression in the liver of the chronic EtFed mice, we hypothesized that KLF4 may mediate alcohol‐induced M2 polarization. We found up‐regulation of KLF4 mRNA and protein levels in the livers of chronic EtFed compared with PF mice (Fig. 1F and G). Furthermore, we studied the expression levels of KLF4 in the KCs and observed a significant increase in EtFed compared with control diet‐fed mice (Fig. 2C). Altogether, these results demonstrated that chronic alcohol feeding in mice led to KLF4 up‐regulation, macrophage activation, and induction of M2 genes in the liver.

Alcohol increases KLF4 expression and transcriptional activity in macrophages in vitro

To test the hypothesis that KLF4 is induced by alcohol, we treated the macrophage RAW264.7 cells with 50 mM EtOH or with well‐established M1 (LPS)‐ and M2 (IL‐4)‐polarizing agents and evaluated macrophage polarization. We found increased KLF4 mRNA (Fig. 3A) and protein (Fig. 3B) after EtOH treatment of RAW macrophages. With the use of a GFP‐based reporter assay, we demonstrated a significant increase in KLF4 transcriptional activity after EtOH treatment for 16–48 h (Fig. 3C). We studied further the KLF4 expression in the presence of different doses of alcohol and observed a dose‐dependent increase in the levels of KLF4 with EtOH treatment in the presence of 50–100 mM EtOH (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Figure 3.

KLF4 expression is increased in macrophages in response to alcohol exposure. RAW264.7 cells were treated with 50 mM EtOH for different time periods, as indicated in the figures, or were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) or mouse IL‐4 (10 ng/ml) for 16 h. (A) KLF4 mRNA levels were also measured by qRT‐PCR. Ctrl, Control. (B) Western blot analysis was performed for KLF4 and β‐actin protein levels after the various treatments. (C) RAW264.7 cells were transiently transfected with a KLF4‐responsive GFP reporter or a GFP reporter controlled by a minimal promoter (Neg Ctrl) or a constitutively expressing GFP construct (Pos Ctrl). Then, the cells were treated with 50 mM EtOH for the indicated time durations. KLF4 transcriptional activity was measured by flow cytometry. (D and E) mRNA expression of M1 and M2 genes in the macrophages was assessed by qRT‐PCR. The data are represented as mean ± sem, n = 3–4, where *P < 0.05.

We found that similar to IL‐4, alcohol treatment increased mRNA expression of M2 markers Arg1, Mrc1, CD163, and IL‐10 in RAW macrophages (Fig. 3E). As expected, expression of M1 genes was induced in the presence of LPS (Fig. 3D). We also observed a significant increase in the levels of TNF‐α and MCP‐1 after 16–48 h of EtOH treatment but not of IL‐1β and iNos (Fig. 3D).

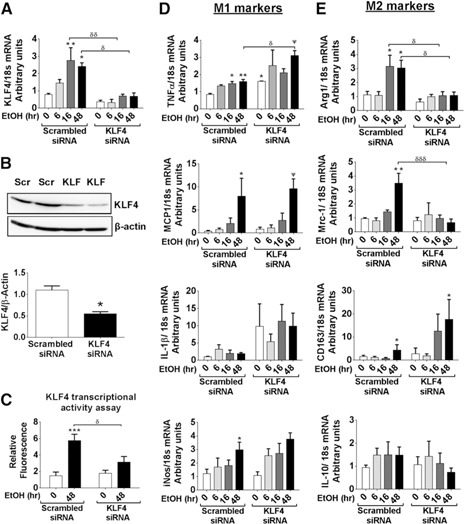

KLF4 is essential for EtOH‐mediated M2 macrophage expression

To study the function of KLF4 in the process of EtOH‐mediated M2 macrophage expression, we performed KLF4 knockdown experiments. RAW 264.7 cells were transfected with KLF4 siRNA that significantly inhibited expression of KLF4 mRNA and protein (Fig. 4A and B). An alcohol‐induced increase in KLF4 transcriptional activity was inhibited in macrophages transfected with KLF4 siRNA compared with scrambled siRNA control (Fig. 4C). KLF4 knockdown resulted in increased expression of TNF‐α and IL‐1β, even in the absence of any EtOH treatment, suggesting that KLF4 functions to suppress M1 gene expression (Fig. 4D). The mRNA levels of TNF‐α were significantly higher in the macrophages that were transfected with KLF4 siRNA and exposed to EtOH for 48 h compared with alcohol‐naϊve cells, suggesting a suppressive effect of KLF4 in alcohol‐mediated TNF‐α expression (Fig. 4D). MCP‐1 and iNos levels were not altered by KLF4 inhibition in the macrophages. KLF4 knockdown resulted in the lowering of the alcohol‐induced M2 genesˈ (Arg1 and Mrc1) expression, except for CD163 mRNA levels, which were increased with KLF4 knockdown and IL‐10 mRNA levels that remained unaltered (Fig. 4E). These results suggest that KLF4 selectively regulates the expression of some of the M2 genes.

Figure 4.

KLF4 knockdown attenuates alcohol‐mediated expression of M2 macrophage markers. RAW264.7 cells were transfected with scrambled (Scr) and KLF4 siRNA and were treated further with 50 mM EtOH for different time periods, as indicated in the bar graphs. (A) mRNA expression of KLF4 measured by qRT‐PCR. (B) KLF4 protein levels, 48 h after transfection, were assessed by Western analysis. (C) KLF4 transcriptional activity was measured by GFP‐reporter assay. (D and E) Gene expression of M1 and M2 markers was assessed by qRT‐PCR. The data are represented as mean ± sem, n = 5–6, where *,ψ,δ P < 0.05, **,δδ P < 0.01, ***,δδδ P < 0.001; * versus scrambled control (0 h), Ψ versus KLF4 siRNA (0 h), and δ versus respective time‐point scrambled siRNA.

Overexpression of KLF4 polarizes macrophages to the M2 phenotype

To determine further the role of KLF4 in macrophage polarization, we performed gain‐of‐function studies by overexpressing KLF4 in the RAW264.7 cells. We observed that KLF4 overexpression increased the mRNA and protein levels of KLF4 (Fig. 5A and B) and KLF4 transcriptional activity, even without alcohol exposure in macrophages (Fig. 5C). KLF4 overexpression alone increased M2 (Arg1 and Mrc1) gene expression and did not significantly affect the levels of M1 genes, indicating the role of KLF4 in inducing M2 polarization (Fig. 5D and E). KLF4 overexpression, in the presence of EtOH, lowered the levels of EtOH‐induced TNF‐α and IL‐1β expression but increased iNos levels (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, the macrophages overexpressing KLF4 displayed a significant increase in the levels of Arg1 and Mrc1 gene expression in the presence of EtOH compared with EtOH‐treated, vector‐transfected controls, suggesting that EtOH‐induced KLF4 is involved in up‐regulating M2 markers (Fig. 5E). However, we found no differences in the CD163 or IL‐10 gene expression between vector‐ or KLF4‐transfected cells. Collectively, these data suggested that KLF4 overexpression induces M2 macrophage polarization by alcohol‐dependent and ‐independent pathways.

Figure 5.

KLF4 overexpression synergizes with alcohol to increase M2 macrophage markers. RAW264.7 cells were transfected with pCMV6‐KLF4 overexpression (OE) construct or the vector control. Then, the cells were treated with 50 mM EtOH for different time periods, as indicated in the figures. (A) mRNA expression of KLF4, measured by qRT‐PCR. (B) KLF4 protein levels, 48 h after transfection, were assessed by Western analysis. (C) KLF4 transcriptional activity was measured by GFP‐reporter assay. (D and E) Gene expression of M1 and M2 markers was assessed by qRT‐PCR. The data are represented as mean ± sem, n = 5–6, where *,ψ,δ P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001; * versus scrambled control (0 h), Ψ versus KLF4 overexpression (0 h), and δ versus respective time‐point vector control.

KLF4 expression is modulated by the transcription factor NF‐κB and by alcohol metabolites

Next, we aimed to investigate mechanisms by which alcohol increased KLF4 in macrophages. It has been shown that NF‐κB and ERK/MAPK signaling pathways are activated in monocyte/macrophages in the presence of alcohol, and both of these pathways can regulate KLF4 expression and function [27, 28, 29, 30–31]. We observed that macrophages treated with MG132, an inhibitor of NF‐κB, showed increased KLF4 levels, with or without EtOH treatment, demonstrating the inhibitory effect of proinflammatory NF‐κB on KLF4 (Fig. 6A). A more specific NF‐κB inhibitor peptide (SN50) also increased KLF4 levels compared with the control peptide (Supplemental Fig. 3). Thus, the results show that the effect of NF‐κB inhibition on KLF4 is independent of EtOH. Although we observed a slight increase in KLF4 mRNA expression in the presence of the ERK/MAPK inhibitor PD98059, there was no change in KLF4 expression induced by EtOH (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

EtOH metabolism enzyme inhibitors affect KLF4 expression. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with an ALDH inhibitor [cyanamide (1 mM)], ADH and CYP2E1 inhibitor [4‐MP (1 mM)], NF‐κB inhibitor [MG132 (5 μM)], ERK/MAPK inhibitor [PD98059 (50 μM)], or DMSO for 1 h and then were treated with 50 mM EtOH for 48 h. RNA, protein, and cell‐culture supernatant were collected. (A) mRNA expression of KLF4 was measured by qRT‐PCR. (B) Alcohol levels were measured in the culture supernatant. (C) ALDH enzyme activity was measured from the cell lysate. (D) KLF4 and β‐actin protein levels were assessed by Western analysis. (E) KLF4 transcriptional activity was measured by GFP‐reporter assay. The data are represented as mean ± sem, n = 3, where * and ψ P < 0.05; * versus −EtOH group and Ψ versus other treatments.

Alcohol and its metabolites can also lead to activation of immune cells in the liver [3, 32]. Alcohol is metabolized by ADH enzyme to break down EtOH, and at high concentration, the MEOS pathway metabolizes alcohol via the CYP2E1 enzyme [33, 34]. Thus, to determine the role of alcohol metabolism in KLF4 activation and macrophage polarization, we first studied the effects of 4‐MP, an inhibitor of ADH and CYP2E1 enzymes [34, 35]. To evaluate the specificity of 4‐MP in alcohol metabolism, the levels of alcohol were measured in macrophage culture supernatant. We observed that there was a significant increase in the levels of alcohol in the presence of 4‐MP compared with medium (Fig. 6B). The rate of alcohol metabolism in macrophages is slow compared with the hepatic cells, which can contribute to the higher levels of alcohol in the culture supernatant after 48 h [28]. Treatment of macrophages with 4‐MP did not alter the alcohol‐induced KLF4 gene expression but increased KLF4 protein expression in the presence of EtOH (Fig. 6A and D).

Acetaldehyde is metabolized to acetate by the ALDH enzyme [36], in which its activity was lowered significantly in the presence of the ALDH enzyme inhibitor, cyanamide, compared with the untreated control (Fig. 6C). Cyanamide lowered KLF4 mRNA and protein expression, suggesting that acetaldehyde also regulates KLF4 levels (Fig. 6A and D). Of all of the inhibitors tested, only 4‐MP and cyanamide modulated alcohol‐induced KLF4 expression, whereas MG132 affected KLF4 levels, irrespective of the presence of EtOH; thus, we investigated the effect of the EtOH metabolism inhibitors on KLF4 transcriptional activity. Macrophages pretreated with 4‐MP and exposed to EtOH showed a significant increase in the transcriptional activity of KLF4. However, in the presence of cyanamide, EtOH‐induced KLF4 transcriptional activity was reduced, suggesting that accumulation of acetaldehyde inhibited KLF4 expression and activity (Fig. 6E).

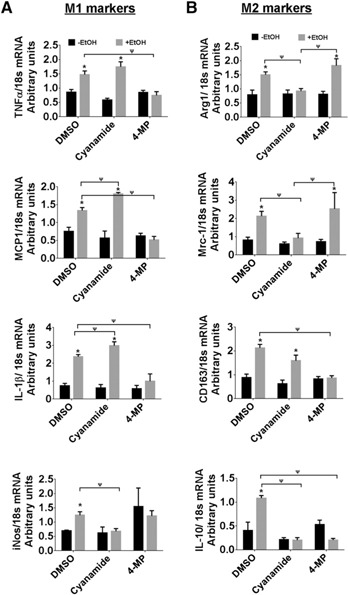

Alcohol and its metabolites regulate macrophage polarization

As alcohol metabolites modulate KLF4 levels, next, we evaluated the expression of M1 and M2 markers in the presence of inhibitors of EtOH metabolism. TNF‐α, MCP‐1, and IL‐1β gene expression was lowered with 4‐MP, whereas it was increased in the presence of cyanamide (Fig. 7A). We observed that alcohol‐induced iNos gene expression was reduced in the presence of cyanamide (Fig. 7A). Next, we studied the effect of the inhibitors on M2 genes. The presence of 4‐MP increased the expression of Arg1 and Mrc1, whereas cyanamide reduced alcohol‐induced expression of Arg1, Mrc1, and IL‐10 (Fig. 7B). There was no change in the alcohol‐induced expression of CD163 in the presence of cyanamide, whereas 4‐MP reduced its expression (Fig. 7B). Collectively, these data suggest that EtOH and its metabolites differently regulate KLF4 expression, which in turn, modulates the expression of M1 and M2 genes.

Figure 7.

ALDH inhibitor reduces KLF4‐mediated M2 macrophage polarization. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with 4‐MP and cyanamide for 1 h and then exposed to 50 mM EtOH for 48 h. Cells were harvested, RNA isolated, and cDNA synthesized. (A and B) Gene expression of M1 and M2 markers was assessed by qRT‐PCR. The data are represented as mean ± sem, n = 3, where * and ψ P < 0.05; * versus −EtOH group and Ψ versus other treatments.

DISCUSSION

Macrophages play an important role in liver injury and repair during ALD. It has been shown that the liver is populated with macrophages belonging to different activation and polarization states, ranging from M1 to M2 macrophages in human ALD [10]. Depending on the gene‐expression profiles in the macrophages, they can exist anywhere in the activation spectrum [13, 37, 38]. In this study, we wanted to decipher the activation state of the macrophages in the EtFed mice and the regulator of such activation. In this study, we show that alcohol induces KLF4 that promotes M2‐type macrophage polarization based on the predominant expression of M2 markers during KLF4 overexpression. Furthermore, our data suggest that whereas alcohol promotes M2 polarization, acetaldehyde appears to have an opposite effect by promoting macrophages toward M1 polarization.

It is important to understand the molecular mechanisms that drive the polarization of the macrophages in ALD. It has been shown that the limiting of M1 KC polarization by M2 KCs in mice reduces progression of ALD [15, 39, 40]. The polarization of macrophages is controlled by transcription factors [32, 41, 42]. KLF4 has been identified as a critical regulator of macrophage polarization and promotes M2 macrophage phenotype and inhibits M1 phenotype [25]. We hypothesized that the M2 macrophages in ALD are regulated by the KLF4 transcription factor. We found increased mRNA and protein expression, as well as transcriptional activity of KLF4 in vivo in the liver and in vitro in macrophages after alcohol treatment. Furthermore, our knockdown and overexpression studies conclusively demonstrated the critical, mechanistic role of KLF4 in inducing the M2 macrophage expression in the presence of alcohol. The inhibitory effect of KLF4 on M1 gene expression was evident from the KLF4 overexpression studies, where the EtOH‐induced expression of TNF‐α, IL‐1β, and MCP‐1 was attenuated, whereas KLF4 siRNA transfection synergized with EtOH to induce M2 marker expression in macrophages. These results demonstrated the EtOH‐dependent and ‐independent role of KLF4 in regulating macrophage polarization.

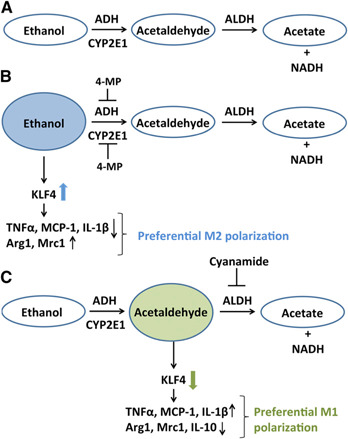

Our study also established the role of EtOH and its metabolites in regulating KLF4. The inhibition of the first step in EtOH metabolism by 4‐MP resulted in an increase in KLF4 expression and transcriptional activity, demonstrating the direct effect of EtOH in regulating KLF4, which in turn, inhibits M1 macrophages and promotes M2 macrophages. Unexpectedly, acetaldehyde accumulation as a result of cyanamide leads to lowered KLF4 levels and activity, which induced M1 and lowered M2 macrophage expression (Fig. 8). It is tempting to speculate that this antagonistic effect of EtOH and its metabolite on KLF4 activity and macrophage polarization could be a probable cause of the mixed macrophage phenotype observed in the liver of ALD patients and alcohol‐treated mice [7, 10].

Figure 8.

EtOH metabolism pathway regulates KLF4 expression and function. (A) ADH and CYP2E1 convert EtOH to acetaldehyde, which is metabolized by ALDH to form acetate and NADH. (B) ADH and CYP2E1 enzyme inhibitor, 4‐MP, inhibits the conversion of EtOH to acetaldehyde. Inhibition of acetaldehyde formation led to increased protein levels and activity of KLF4. Increased KLF4 leads to decreased M1 marker and increased M2 marker expression (C) Cyanamide, which is an ALDH inhibitor, causes increased accumulation of acetaldehyde. In the presence of cyanamide, KLF4 expression and activity are reduced, which in turn, leads to up‐regulation of M1 macrophage phenotype and lowers M2 gene expression.

KLF4 is a zinc finger transcription factor that is known to be involved in the cell‐cycle regulation, differentiation, hematopoiesis, and immune responses [24, 43, 44]. Gene‐targeting studies have shown that KLF4 is critical for monocyte differentiation and macrophage polarization [25, 45]. With respect to M2 polarization, previous studies indicate that KLF4 cooperates with STAT6 to induce M2 targets, such as Arg1, following IL‐4 stimulation [25]. This type of inductive and cooperative relationship has also been observed between STAT6 and PPARγ in macrophages during M2 activation [40]. Alcohol exposure has been shown to increase STAT6 phosphorylation [46]. Interactions and cooperation between the Stat6/KLF4/PPARγ axis may allow for optimal and sustained M2 activation. We observed that KLF4 can differentially regulate M1 and M2 genes that are expressed in the macrophages during ALD. KLF4 induces M2 genes, such as Arg1 and Mrc1, whereas it reduces the expression of M1 markers. Our studies show that Arg1 and Mrc1 are induced by KLF4 in the presence of EtOH in macrophages, which might be a result of the cooperative interaction of KLF4 and STAT6. The induction of KLF4 provides a molecular mechanism to not only induce the M2 phenotype but also to inhibit the M1 pathway. The importance of the inhibition of proinflammatory target of KLF4 was highlighted by our gain‐ and loss‐of‐function studies. Furthermore, our observation that KLF4 deficiency further enhances the expression of alcohol‐induced TNF‐α suggested that KLF4 is important in suppression of proinflammatory genes in macrophages. Studies have demonstrated that the anti‐inflammatory effect occurs, at least in part, through the ability of KLF4 to inhibit NF‐κB transcriptional activity by sequestering the coactivators required for optimal NF‐κB transcriptional activity [25, 26, 47]. However, not all of the M2 genes are regulated in a similar way, as we observed an increased expression of CD163 in macrophages transfected with KLF4 siRNA and exposed to alcohol. Although CD163+ macrophages have an anti‐inflammatory function, they are highly expressed at sites of inflammation [48]. Studies have also shown an association of CD163‐expressing cells and TNF‐α production [48, 49–50]. The targeting and elimination of CD163+ macrophages lead to attenuation of LPS‐mediated TNF‐α production [48] Reduction in CD163‐positive cells with TNF‐α therapy suggested a role of TNF‐α in regulating CD163‐expressing macrophages [51, 52]. Thus, it is likely that TNF‐α levels in macrophages exposed to alcohol might regulate the CD163 expression.

Metabolism of a high‐tissue level of alcohol leads to generation of toxic byproducts [7]. ADH, present in the cell cytosol, converts EtOH to acetaldehyde. CYP2E1, present predominantly in the microsomes, metabolizes EtOH to acetaldehyde during high EtOH concentrations (Fig. 8). Acetaldehyde is metabolized mainly by ALDH2 in the mitochondria to form acetate. Alcohol metabolites have been shown to modulate the levels of various transcription factors, such as NF‐κB and AP‐1, which can, in turn, modulate the macrophage gene expression [36, 53]. We observed that the process of EtOH metabolism and the metabolites affect the levels and activity of the transcription factor KLF4. 4‐MP inhibits the conversion of EtOH to acetaldehyde, a highly reactive and toxic byproduct [34, 35]. Inhibition of acetaldehyde formation led to increased protein levels and activity of KLF4 and M2 marker expression. This suggests that alcohol itself induces KLF4 and promotes M2 polarization. In contrast, acetaldehyde accumulation by cyanamide reduced the levels of KLF4 and its activity, which in turn, led to higher expression of M1 markers in the macrophages. In a previous study, it has been shown that cyanamide potentiates EtOH‐induced activation of NF‐κB and AP‐1 by modulating directly its DNA‐binding activity [36]. Thus, it is likely that the increased activation of NF‐κB negatively regulates alcohol‐induced KLF4 activity. Further studies are required to decipher the interactions of KLF4 with other macrophage‐regulating transcription factors during ALD. Furthermore, transcriptome‐based analysis of macrophages from EtFed mice is required to identify all of the different activation states of macrophages during ALD [13]. Nevertheless, the ability of KLF4 to regulate macrophage activation and polarization during ALD has potentially broad implications for the role of this transcription factor in ALD progression and pathogenesis.

AUTHORSHIP

B.S., S.B., and G.S. designed research. B.S., S.B., N.H., K.K., and G.S. performed research. B.S., S.B., N.H., K.K., and G.S. analyzed data. B.S. and G.S. wrote the paper.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary data

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism U.S. National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AA011576, R01 AA008577, and R01 AA020744 (to G.S.). The authors thank Donna Catalano for the assistance with the mice and the members of the Szabo lab for valuable discussion and assistance. The authors also thank Merin MacDonald for administrative assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yoon, Y., Yi, H.Y. (2012) Liver cirrhosis mortality in the United States, 1970–2009. Surveillance Report #93. NIH, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Bethesda, MD. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Rehm, J., Mathers, C., Popova, S., Thavorncharoensap, M., Teerawattananon, Y., Patra, J. (2009) Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol‐use disorders. Lancet 373, 2223–2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ajakaiye, M., Jacob, A., Wu, R., Nicastro, J.M., Coppa, G.F., Wang, P. (2011) Alcohol and hepatocyte‐Kupffer cell interaction (review). Mol. Med. Rep. 4, 597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanyal, A.J., Yoon, S.K., Lencioni, R. (2010) The etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma and consequences for treatment. Oncologist 15 (Suppl 4), 14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu, D., Cederbaum, A.I. (2003) Alcohol, oxidative stress, and free radical damage. Alcohol Res. Health 27, 277–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sid, B., Verrax, J., Calderon, P.B. (2013) Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of alcohol‐induced liver disease. Free Radic. Res. 47, 894–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang, M., You, Q., Lor, K., Chen, F., Gao, B., Ju, C. (2014) Chronic alcohol ingestion modulates hepatic macrophage populations and functions in mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 96, 657–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tacke, F. (2012) Functional role of intrahepatic monocyte subsets for the progression of liver inflammation and liver fibrosis in vivo. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 5 (Suppl 1 Proceedings of Fibroproliferative disorders: from biochemical analysis to targeted therapies Petro E Petrides and David Brenner), S27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Gordon, S., Martinez, F.O. (2010) Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity 32, 593–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, J., French, B., Morgan, T., French, S.W. (2014) The liver is populated by a broad spectrum of markers for macrophages. In alcoholic hepatitis the macrophages are M1 and M2. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 96, 118–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.French, S.W., Lee, J., Zhong, J., Morgan, T.R., Buslon, V., Lungo, W., French, B.A. (2012) Alcoholic liver disease—hepatocellular carcinoma transformation. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 3, 174–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sica, A., Mantovani, A. (2012) Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 787–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue, J., Schmidt, S.V., Sander, J., Draffehn, A., Krebs, W., Quester, I., De Nardo, D., Gohel, T.D., Emde, M., Schmidleithner, L., Ganesan, H., Nino‐Castro, A., Mallmann, M.R., Labzin, L., Theis, H., Kraut, M., Beyer, M., Latz, E., Freeman, T.C., Ulas, T., Schultze, J.L. (2014) Transcriptome‐based network analysis reveals a spectrum model of human macrophage activation. Immunity 40, 274–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez, F.O., Gordon, S. (2014) The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000 Prime Rep. 6, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan, J., Benkdane, M., Alons, E., Lotersztajn, S., Pavoine, C. (2014) M2 Kupffer cells promote hepatocyte senescence: an IL‐6‐dependent protective mechanism against alcoholic liver disease. Am. J. Pathol. 184, 1763–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wan, J., Benkdane, M., Teixeira‐Clerc, F., Bonnafous, S., Louvet, A., Lafdil, F., Pecker, F., Tran, A., Gual, P., Mallat, A., Lotersztajn, S., Pavoine, C. (2014) M2 Kupffer cells promote M1 Kupffer cell apoptosis: a protective mechanism against alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 59, 130–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waddell, S.J., Popper, S.J., Rubins, K.H., Griffiths, M.J., Brown, P.O., Levin, M., Relman, D.A. (2010) Dissecting interferon‐induced transcriptional programs in human peripheral blood cells. PLoS ONE 5, e9753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pauleau, A.L., Rutschman, R., Lang, R., Pernis, A., Watowich, S.S., Murray, P.J. (2004) Enhancer‐mediated control of macrophage‐specific arginase I expression. J. Immunol. 172, 7565–7573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang, K., Reilly, S.M., Karabacak, V., Gangl, M.R., Fitzgerald, K., Hatano, B., Lee, C.H. (2008) Adipocyte‐derived Th2 cytokines and myeloid PPARdelta regulate macrophage polarization and insulin sensitivity. Cell Metab. 7, 485–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vats, D., Mukundan, L., Odegaard, J.I., Zhang, L., Smith, K.L., Morel, C.R., Wagner, R.A., Greaves, D.R., Murray, P.J., Chawla, A. (2006) Oxidative metabolism and PGC‐1beta attenuate macrophage‐mediated inflammation. Cell Metab. 4, 13–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takeda, N., O'Dea, E.L., Doedens, A., Kim, J.W., Weidemann, A., Stockmann, C., Asagiri, M., Simon, M.C., Hoffmann, A., Johnson, R.S. (2010) Differential activation and antagonistic function of HIF‐alpha isoforms in macrophages are essential for NO homeostasis. Genes Dev. 24, 491–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouhlel, M.A., Derudas, B., Rigamonti, E., Dievart, R., Brozek, J., Haulon, S., Zawadzki, C., Jude, B., Torpier, G., Marx, N., Staels, B., Chinetti‐Gbaguidi, G. (2007) PPARgamma activation primes human monocytes into alternative M2 macrophages with anti‐inflammatory properties. Cell Metab. 6, 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liuzzi, J.P., Guo, L., Chang, S.M., Cousins, R.J. (2009) Krüppel‐like factor 4 regulates adaptive expression of the zinc transporter Zip4 in mouse small intestine. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 296, G517–G523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alder, J.K., Georgantas, R.W., Hildreth, R.L., Kaplan, I.M., Morisot, S., Yu, X., McDevitt, M., Civin, C.I. (2008) Kruppel‐like factor 4 is essential for inflammatory monocyte differentiation in vivo. J. Immunol. 180, 5645–5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao, X., Sharma, N., Kapadia, F., Zhou, G., Lu, Y., Hong, H., Paruchuri, K., Mahabeleshwar, G.H., Dalmas, E., Venteclef, N., Flask, C.A., Kim, J., Doreian, B.W., Lu, K.Q., Kaestner, K.H., Hamik, A., Clément, K., Jain, M.K. (2011) Krüppel‐like factor 4 regulates macrophage polarization. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 2736–2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen, K.L., Hamik, A., Jain, M.K., McCrae, K.R. (2011) Endothelial cell activation by antiphospholipid antibodies is modulated by Kruppel‐like transcription factors. Blood 117, 6383–6391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bala, S., Marcos, M., Kodys, K., Csak, T., Catalano, D., Mandrekar, P., Szabo, G. (2011) Up‐regulation of microRNA‐155 in macrophages contributes to increased tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFalpha) production via increased mRNA half‐life in alcoholic liver disease. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1436–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mandrekar, P., Bala, S., Catalano, D., Kodys, K., Szabo, G. (2009) The opposite effects of acute and chronic alcohol on lipopolysaccharide‐induced inflammation are linked to IRAK‐M in human monocytes. J. Immunol. 183, 1320–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim, M.O., Kim, S.H., Cho, Y.Y., Nadas, J., Jeong, C.H., Yao, K., Kim, D.J., Yu, D.H., Keum, Y.S., Lee, K.Y., Huang, Z., Bode, A.M., Dong, Z. (2012) ERK1 and ERK2 regulate embryonic stem cell self‐renewal through phosphorylation of Klf4. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaushik, D.K., Gupta, M., Das, S., Basu, A. (2010) Krüppel‐like factor 4, a novel transcription factor regulates microglial activation and subsequent neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflammation 7, 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida, T., Kaestner, K.H., Owens, G.K. (2008) Conditional deletion of Krüppel‐like factor 4 delays downregulation of smooth muscle cell differentiation markers but accelerates neointimal formation following vascular injury. Circ. Res. 102, 1548–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okabe, Y., Medzhitov, R. (2014) Tissue‐specific signals control reversible program of localization and functional polarization of macrophages. Cell 157, 832–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zakhari, S. (2006) Overview: how is alcohol metabolized by the body? Alcohol Res. Health 29, 245–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin, M., Ande, A., Kumar, A., Kumar, S. (2013) Regulation of cytochrome P450 2e1 expression by ethanol: role of oxidative stress‐mediated pkc/jnk/sp1 pathway. Cell Death Dis. 4, e554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swaminathan, K., Clemens, D.L., Dey, A. (2013) Inhibition of CYP2E1 leads to decreased malondialdehyde‐acetaldehyde adduct formation in VL‐17A cells under chronic alcohol exposure. Life Sci. 92, 325–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Román, J., Colell, A., Blasco, C., Caballeria, J., Parás, A., Rodás, J., Fernández‐Checa, J.C. (1999) Differential role of ethanol and acetaldehyde in the induction of oxidative stress in HEP G2 cells: effect on transcription factors AP‐1 and NF‐kappaB. Hepatology 30, 1473–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stout, R.D., Suttles, J. (2004) Functional plasticity of macrophages: reversible adaptation to changing microenvironments. J. Leukoc. Biol. 76, 509–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murray, P.J., Allen, J.E., Biswas, S.K., Fisher, E.A., Gilroy, D.W., Goerdt, S., Gordon, S., Hamilton, J.A., Ivashkiv, L.B., Lawrence, T., Locati, M., Mantovani, A., Martinez, F.O., Mege, J.L., Mosser, D.M., Natoli, G., Saeij, J.P., Schultze, J.L., Shirey, K.A., Sica, A., Suttles, J., Udalova, I., van Ginderachter, J.A., Vogel, S.N., Wynn, T.A. (2014) Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity 41, 14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Louvet, A., Teixeira‐Clerc, F., Chobert, M.N., Deveaux, V., Pavoine, C., Zimmer, A., Pecker, F., Mallat, A., Lotersztajn, S. (2011) Cannabinoid CB2 receptors protect against alcoholic liver disease by regulating Kupffer cell polarization in mice. Hepatology 54, 1217–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Odegaard, J.I., Ricardo‐Gonzalez, R.R., Goforth, M.H., Morel, C.R., Subramanian, V., Mukundan, L., Red Eagle, A., Vats, D., Brombacher, F., Ferrante, A.W., Chawla, A. (2007) Macrophage‐specific PPARgamma controls alternative activation and improves insulin resistance. Nature 447, 1116–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao, S., Mao, F., Zhang, B., Zhang, L., Zhang, X., Wang, M., Yan, Y., Yang, T., Zhang, J., Zhu, W., Qian, H., Xu, W. (2014) Mouse bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells induce macrophage M2 polarization through the nuclear factor‐κB and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 pathways. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 239, 366–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou, D., Huang, C., Lin, Z., Zhan, S., Kong, L., Fang, C., Li, J. (2014) Macrophage polarization and function with emphasis on the evolving roles of coordinated regulation of cellular signaling pathways. Cell. Signal. 26, 192–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feinberg, M.W., Cao, Z., Wara, A.K., Lebedeva, M.A., Senbanerjee, S., Jain, M.K. (2005) Kruppel‐like factor 4 is a mediator of proinflammatory signaling in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38247–38258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghaleb, A.M., Nandan, M.O., Chanchevalap, S., Dalton, W.B., Hisamuddin, I.M., Yang, V.W. (2005) Krüppel‐like factors 4 and 5: the yin and yang regulators of cellular proliferation. Cell Res. 15, 92–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feinberg, M.W., Wara, A.K., Cao, Z., Lebedeva, M.A., Rosenbauer, F., Iwasaki, H., Hirai, H., Katz, J.P., Haspel, R.L., Gray, S., Akashi, K., Segre, J., Kaestner, K.H., Tenen, D.G., Jain, M.K. (2007) The Kruppel‐like factor KLF4 is a critical regulator of monocyte differentiation. EMBO J. 26, 4138–4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell, P.O., Jensen, J.S., Ritzenthaler, J.D., Roman, J., Pelaez, A., Guidot, D.M. (2009) Alcohol primes the airway for increased interleukin‐13 signaling. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 33, 505–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Evans, P.M., Chen, X., Zhang, W., Liu, C. (2010) KLF4 interacts with beta‐catenin/TCF4 and blocks p300/CBP recruitment by beta‐catenin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 372–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Graversen, J.H., Svendsen, P., Dagnæs‐Hansen, F., Dal, J., Anton, G., Etzerodt, A., Petersen, M.D., Christensen, P.A., M⊘ller, H.J., Moestrup, S.K. (2012) Targeting the hemoglobin scavenger receptor CD163 in macrophages highly increases the anti‐inflammatory potency of dexamethasone. Mol. Ther. 20, 1550–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fabriek, B.O., van Bruggen, R., Deng, D.M., Ligtenberg, A.J., Nazmi, K., Schornagel, K., Vloet, R.P., Dijkstra, C.D., van den Berg, T.K. (2009) The macrophage scavenger receptor CD163 functions as an innate immune sensor for bacteria. Blood 113, 887–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiao, K., Zhang, J., Zhang, M., Wei, Y., Wu, Y., Qiu, Z.Y., He, J., Cao, Y., Hu, J., Zhu, H., Niu, L.N., Cao, X., Yang, K., Wang, M.Q. (2013) The identification of CD163 expressing phagocytic chondrocytes in joint cartilage and its novel scavenger role in cartilage degradation. PLoS ONE 8, e53312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baeten, D., Demetter, P., Cuvelier, C.A., Kruithof, E., Van Damme, N., De Vos, M., Veys, E.M., De Keyser, F. (2002) Macrophages expressing the scavenger receptor CD163: a link between immune alterations of the gut and synovial inflammation in spondyloarthropathy. J. Pathol. 196, 343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Polfliet, M.M., Fabriek, B.O., Daniels, W.P., Dijkstra, C.D., van den Berg, T.K. (2006) The rat macrophage scavenger receptor CD163: expression, regulation and role in inflammatory mediator production. Immunobiology 211, 419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tugal, D., Liao, X., Jain, M.K. (2013) Transcriptional control of macrophage polarization. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33, 1135–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data