Short abstract

NK1.1+ cell activation contributes to the persistence of inflammation leading to end organ damage in the liver and gut after HS/T.

Keywords: natural killer cell, T cell, leukocytes, cytokines

Abstract

Various cell populations expressing NK1.1 contribute to innate host defense and systemic inflammatory responses, but their role in hemorrhagic shock and trauma remains uncertain. NK1.1+ cells were depleted by i.p. administration of anti‐NK1.1 (or isotype control) on two consecutive days, followed by hemorrhagic shock with resuscitation and peripheral tissue trauma (HS/T). The plasma levels of IL‐6, MCP‐1, alanine transaminase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured at 6 and 24 h. Histology in liver and gut were examined at 6 and 24 h. The number of NK cells, NKT cells, neutrophils, and macrophages in liver, as well as intracellular staining for TNF‐α, IFN‐γ, and MCP‐1 in liver cell populations were determined by flow cytometry. Control mice subjected to HS/T exhibited end organ damage manifested by marked increases in circulating ALT, AST, and MCP‐1 levels, as well as histologic evidence of hepatic necrosis and gut injury. Although NK1.1+ cell–depleted mice exhibited a similar degree of organ damage as nondepleted animals at 6 h, NK1.1+ cell depletion resulted in marked suppression of both liver and gut injury by 24 h after HS/T. These findings indicate that NK1.1+ cells contribute to the persistence of inflammation leading to end organ damage in the liver and gut.

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CCL2/MCP‐1

monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1

- HS/T

hemorrhagic shock + resuscitation and peripheral tissue trauma

- ILC

innate lymphoid cell

- MAP

mean arterial blood pressure

- PMN

PMN leukocyte (neutrophil)

- SIRS

systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Introduction

Injury, whether intentional or unintentional, remains the leading cause of death in people younger than 54 y in the United States [1]. Severe, traumatic injury, often accompanied by hemorrhagic shock, leads to a SIRS that can cause organ injury and dysfunction. Among the organs that are subjected to injury are the intestine [2, 3] and liver [4]. An excessive and uncontrolled, SIRS is associated with organ failure, immunosuppression, and increased susceptibility to nosocomial infection after trauma. The SIRS is a result of activation of innate immune mechanisms, such as TLR signaling [4, 5] and the complement system [6]. Cellular components of the innate immune system are also important to the initial inflammatory response after HS/T. For example, mast cells are a key cellular component contributing to the pathobiology of severe injury [7]. However, the role of NK and NKT cells in either the inflammatory response or end organ damage after HS/T has not been established.

NK cells, as large granular lymphocytes, have an important role in the early stages of innate immune responses because of their two major functions: cytotoxicity and cytokine production, especially of IFN‐γ. Thus, NK cells have a critical role in the development of systemic inflammatory reactions by producing IFN‐γ and by subsequent activation of macrophages [8]. Recently, it was reported that NK cells also contributed to the pathogenic pathways in models of infection and sepsis, as well as a model that combined trauma and sepsis [9, 10, 11, 12–13].

Like NK cells, NKT cells are identified as regulators of the innate immune response. NKT cells are a unique subset of T lymphocytes that also express typical NK cell markers, such as NK1.1 and Ly49A markers [14]. Upon stimulation of their TCRs through CD1d‐presented glycolipid Ag, NKT cells can be rapidly activated to secrete cytokines, such as IFN‐γ and TNF‐α. Recent evidence suggests that activation of NKT cells also contributes to the development and progression of tissue injury in acute models of immune‐mediated organ injury [15, 16].

The current study was undertaken to delineate the roles of NK and NKT cells, specifically to HS/T‐induced inflammation and organ injury, using a model combining severe hemorrhagic shock and peripheral tissue trauma. We show that the depletion of NK1.1+ cells suppresses liver and gut injury as well as the capacity of liver macrophages to produce TNF‐α and MCP‐1/CCL‐2. NK and NKT cells appear to have a role in sustaining the SIRS and end organ damage after severe systemic injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Mice used in the experimental protocols were housed in accordance with University of Pittsburgh, Division of Laboratory Animal Resources, and all procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male C57BL/6 (WT) mice (8 –12 wk old; 20–30 g body weight) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and housed under specific pathogen‐free conditions with free access to standard laboratory feed and water.

NK1.1 Ab treatments

The depletion of NK1.1+ cells was accomplished before induction of HS/T by i.p. administration of 2 doses of 75 μg NK1.1‐PK136 Ab (BioXCell, West Lebanon, NH, USA) in 200 μl saline on successive days [17]; control mice received 2, 75‐μg doses of isotype control Ab or 200 μl saline.

Mouse model of HS/T

Pseudofracture was performed, as described previously [18]. In brief, the soft tissue injury in the form of a muscle crush injury to the thigh musculature bilaterally was followed by an injection of a crushed bone solution. Unilateral groin dissections were performed, and the femoral artery was cannulated and flushed with heparin sulfate (Pharmacia & Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI, USA). The groin catheter was connected to a blood pressure transducer (MicroMed, Houston, TX, USA) for continuous MAP readings. Mice hemorrhaged to a MAP reading of 25 mm Hg over 5 min, and the MAP was maintained at 25 mm Hg for 150 min. The mice were resuscitated with 2 times the maximal shed blood volume of lactated Ringer solution. At 6 and 24 h, mice were sacrificed, plasma was obtained for cytokines IL‐6 and MCP‐1, with levels quantified with commercial ELISA kits (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), and levels of ALT and AST were determined (measured with the Dri‐Chem 7000 chemistry analyzer; Heska, Loveland, CO, USA).

Mouse hepatic nonparenchymal cell isolation

The liver was perfused with PBS through the right ventricle of the heart before removal, cut into small pieces, and digested with 1.3 mg/ml Collagenase H (F. Hoffmann‐La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 30 min at 37°C under rotation (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA, USA). Samples were pressed through 100‐μm cell strainers (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), washed, and nonparenchymal cell were separated from hepatocytes by centrifugation at 17–21 g for 4 min and purified further with a 30/70% Percoll gradient (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom).

Flow cytometry

Single hepatic‐cell suspensions were stained with a combination of the following fluorescently conjugated mAbs: AF700‐conjugated CD45 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), APC‐conjugated NK1.1 (BD Pharmingen; BD Biosciences), FITC‐conjugated DX5 (eBioscience), PE‐Cy5.5‐conjugated CD3 (eBioscience), APC‐Cy7‐conjugated Ly6G (eBioscience), and eFluor 450‐conjugated F4/80 (eBioscience). For measurement of intracellular cytokine expression, single hepatic‐cell suspensions were stimulated ex vivo for 4 h in the presence of PMA and ionomycin, followed by surface staining for a combination of the Abs listed above, fixed, and permeabilized, using a commercially available kit (eBioscience), and stained with TNF‐α APC‐Cy7 (BD Pharmingen; BD Biosciences), IFN‐γ PE‐Cy7(eBioscience), or MCP‐1 PE (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). Dead cells were excluded from analysis by using Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 506 stain (eBioscience). Samples were acquired on a BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

Histopathology

For histopathologic examinations, liver, lungs, and gut (ileum) were fixed with 10% formalin for 2 d, embedded in paraffin, and 5‐μm sections were stained with H&E.

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as means ± sem. Comparisons among more than 2 groups were performed with 1‐way ANOVA and a post hoc Newman‐Keuls test. Comparisons between 2 groups were performed with unpaired t test. Probability values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. When individual studies are discussed, they are representative of ≥3 independent studies.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

NK1.1+ cells contribute to organ damage in mice after HS/T

HS/T, as seen after traumatic events in humans, activates inflammatory responses leading to end organ damage. To determine the contribution of NK1.1+ cells to liver injury after HS/T, the levels of ALT and AST were measured at 6 and 24 h after HS/T. NK1.1+ cells were depleted by i.p. administration of 75 µg PK136 Ab in C57BL/6 mice, on each of the 2 d before initiation of resuscitated HS and tissue injury (HS/T). Injection of isotype IgG or saline served as controls for the NK1.1 Ab–treated group. We confirmed that this regimen of NK1.1 Ab administration effectively depleted NK cells in spleen, liver, lung, and blood (see Supplemental data).

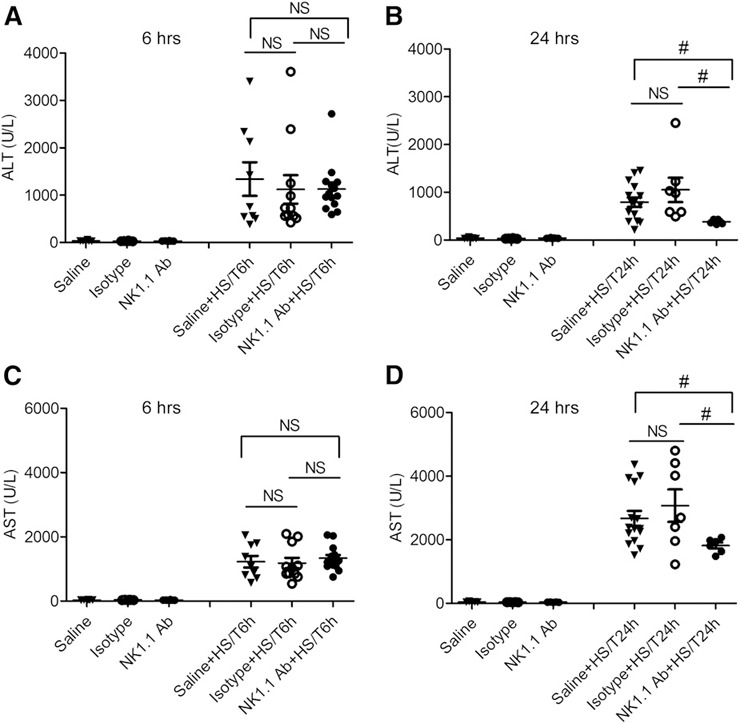

As shown in Fig. 1 , no significant differences in baseline ALT and AST levels were observed in C57BL/6 mice with or without NK1.1+ cell depletion (Fig. 1A–D). The levels of ALT and AST increased significantly at 6 and 24 h after HS/T with the highest elevation detected at 6 h for ALT (Fig. 1A) and 24 h for AST (Fig. 1D). After HS/T, the differences in ALT and AST at 6 h between NK1.1 Abs and isotype Abs or saline‐treated groups were negligible. However, at 24 h after HS/T, NK1.1+ cell depletion resulted in significantly (P < 0.05) lower levels of ALT and AST than the control groups had. Those data show that NK1.1+ cells promote liver damage that becomes apparent by 24 h after HS/T.

Figure 1.

Effect of NK1.1+ cells on plasma levels of ALT and AST at 6 and 24 h after HS/T. C57BL/6 mice were injected with NK1.1 Ab, saline, or isotype IgG 48 and 24 h before hemorrhagic shock and pseudofracture (HS/T). Plasma levels of ALT and AST were measured for analysis of liver damage. (A and B) ALT level in mice after HS/T at 6 h (A) or 24 h (B). (C and D) AST level in mice after HS/T at 6 h (C) or 24 h (D). Data represent means ± sem; n = 6–15 mice/group. #P < 0.05 vs. saline + HS/T at 24 h.

Histopathologic assessment of organ injury after HS/T

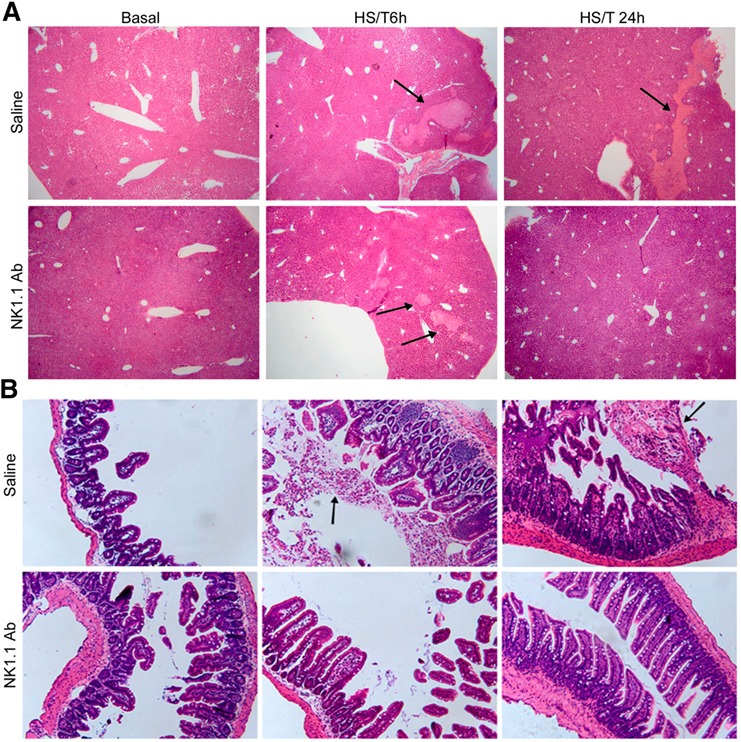

End organ injury was further evaluated by histopathologic examination of tissues after HS/T. Although major histologic differences were seen when assessing injury to the liver and gut between the control and NK1.1‐depleted mice after HS/T (discussed further below), no differences were observed in the histologic scoring of lung injury (data not shown). Liver injury was scored on a 0–3 scale, with a score of 0 indicating healthy organ histology; ± indicating tiny/microscopic foci (<10 hepatocytes) showing coagulative‐type necrosis with minimal neutrophilia; 1 indicating confluent (>1 lobule) area of coagulative‐type necrosis with neutrophilia involving >1/3 of the tissue section; 2 indicating confluent areas of necrosis with neutrophilia involving 1/3–2/3 of the tissue section; and 3 indicating confluent areas of necrosis with neutrophilia involving >2/3 of the tissue section. Intestinal sections were graded as 1 indicating focal villous tip necrosis with occasional pseudomembranous area involving <1/3 of tissue section; 2 indicating focal villous tip necrosis with pseudomembranous area involving 1/3–2/3 of tissue section; 3 indicating focal villous tip necrosis with pseudomembranous area involving >2/3 of tissue section. For the liver, at 6 h, ± indicated the level of injury was observed, and a ± to 1 injury score at 24 h. The liver sections in mice treated with saline or NK1.1 Ab showed similar areas of necrosis at 6 h after HS/T ( Fig. 2A ). However, persistent areas of necrosis were only seen in the control group and not in the NK1.1+ cell‐depleted mice at 24 h. For the intestine, an average injury score of 1 was observed at 6 h, and by 24 h, the injury score averaged 1–3 for the control groups subjected to HS/T. In contrast the injury score was 0 at both 6 and 24 h in the NK1.1‐depleted group subjected to HS/T. Impressive inflammatory cell infiltrates appeared in the gut lumen in control, but not NK1.1 Ab‐treated, mice at 6 and 24 h after HS/T (Fig. 2 B). Thus, the gut appeared to be structurally normal in NK1.1+ cell‐depleted mice after HS/T. It is well recognized that shock or major trauma leads to a decrease in mesenteric perfusion, resulting in an ischemia‐reperfusion–induced gut inflammatory response. HS/T induces breakdown of the intestinal luminal mucus layer, and there is a direct correlation between loss of the mucus layer and the severity of villus injury [2]. Some of the gut injury results from generation of free‐radical species [3]. Our results indicated that NK 1.1+ cells are part of the local inflammatory response that leads to inflammation and villus injury in the gut after HS/T. In the liver, NK 1.1+ cells appear to sustain the processes involved in driving liver injury after HS/T.

Figure 2.

Effect of NK1.1+ cells on the histopathology of liver and gut at 6 h and 24 h after HS/T. (A) Histopathology of liver tissue at 6 and 24 h after HS/T. (B) Histopathology of gut tissue at 6 and 24 h after HS/T. Paraffin‐embedded sections were prepared from the liver and gut of C57BL/6 mice treated with saline or NK1.1 Ab at 6 and 24 h after HS/T and underwent H&E staining. Slides were representative of 6–10 mice/group. The liver sections original magnifications, ×40; the gut sections were original magnifications, ×200. Arrows indicate necrosis in the liver or inflammatory cell infiltration in the gut lumen.

NK1.1+ cells prolong the SIRS following HS/T

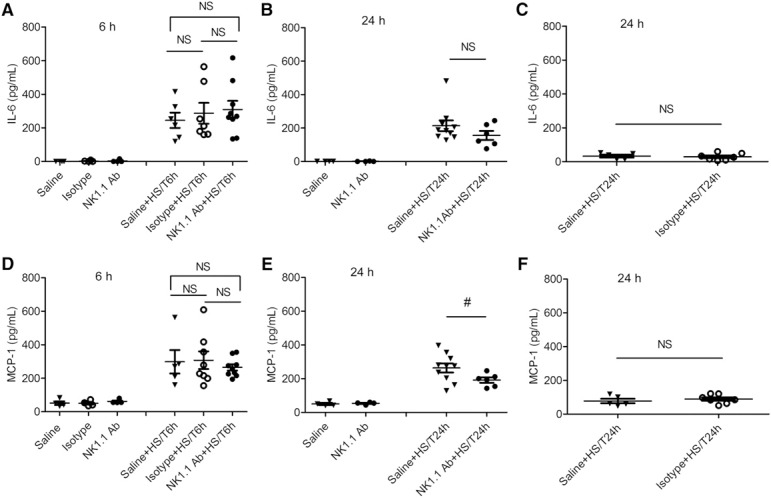

HS/T induces an SIRS, manifested by increases in circulating levels of cytokines and chemokines [19, 20, 21–22]. IL‐6 and MCP‐1 are among the most consistently elevated inflammatory mediators after trauma [21, 22]. Plasma levels of IL‐6 and MCP‐1 were measured to assess the SIRS at 6 and 24 h after HS/T. Significant increases in both IL‐6 ( Fig. 3A–C ) and MCP‐1 (Fig. 3D–F) were induced by HS/T, as expected. Treatment with isotype control Ab or NK1.1 Ab had no effect on the baseline levels of IL‐6 or the increases induced by HS/T (Fig. 3A–C). There was also no difference between the control groups and NK1.1 Ab‐treated groups for MCP‐1 at 6 h (Fig. 3D). In contrast, at 24 h, the NK1.1 Ab‐treated mice subjected to HS/T had significantly lower MCP‐1 levels than the control group subjected to HS/T had (Fig. 3E). Those data suggest that NK1.1+ cells selectively extend components of the inflammatory response after HS/T.

Figure 3.

Effect of NK1.1+ cells on plasma levels of IL‐6 and MCP‐1 in mice at 6 h and 24 h after HS/T. (A–C) IL‐6 level in the plasma of mice with HS/T at 6 h (A) and 24 h (B and C). (D–F) MCP‐1 level in the plasma of mice with HS/T at 6 h (D) and 24 h (E and F). Data represent means ± sem; n = 4–10 mice/group. #P < 0.05 vs. saline + HS/T at 24 h.

HS/T alters the number of NK cells, neutrophils, B cells, and macrophages in the liver

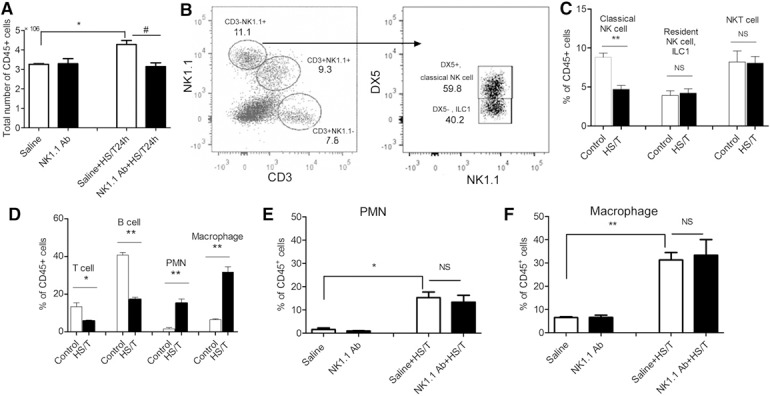

The liver is selectively enriched in NK cells (including classic NK cells, resident NK cells, ILC1) and NKT cells [23]. We analyzed the changes in leukocyte subsets in the liver at 24 h after HS/T, a time point when the degree of liver damage was clearly reduced if NK1.1+ cells were depleted. As shown in Fig. 4A , HS/T induced greater leukocyte infiltration into the liver by 24 h in control mice than that in NK1.1+ cell depleted mice. Of the leukocytes in the liver at baseline (Fig. 4B) 7.8% of the CD45+ cells in the liver were T cells (CD3+, NK1.1‐), 9.3% NKT cells (CD3+, NK1.1+) and 11.1% NK cells (CD3‐, NK1.1+). Of the CD3‐ NK1.1+ or NK cells, nearly 60% were classic (DX5+) NK cells and 40% were DX5‐ or innate lymphoid cells (ILC1). HS/T induced a significant reduction in the proportion of classic NK cells but no change in the percent of ILC1 or NKT cells in the liver (Fig. 4C). These results confirm the findings of others that liver resident NK cells or ILC1 do not migrate [24, 25] after an inflammatory stimulus.

Figure 4.

Proportions of various cell populations in the liver at 24 h after HS/T. (A) The absolute number of viable leukocytes in the liver at 24 h after HS/T. (B) The proportions of NK and T cell populations were determined. NKT cells were CD3+NK1.1+, T cells were CD3+NK1.1−, and NK cells were CD3−NK1.1+. The NK cells were further divided into a DX5+ population (classic NK cells) and a DX5− population or innate lymphoid cells (ILC1) [24, 25]. (C) The changes in the proportion of NK, ILC1, and NKT cells after HS/T (n of 10/group) compared with control liver (n of 5/group) are depicted. (D) The proportions of T cells (CD3+NK1.1−), B cells (CD45R+), PMNs (Gr1+), and macrophages (F4/80+) in the liver of control (n of 3–5/group) and HS/T (n of 8–11/group) mice are depicted. (E and F) The proportions of PMNs (Gr1+) (E) and macrophages (F4/80+) (F) in the liver of mice with HS/T at 24 h are depicted (n of 3–11/group). Cells harvested from liver were phenotyped by gating on viable CD45+ cells. Data represent means ± sem; *P < 0.05 vs. control (saline) group, **P < 0.01 vs. control (saline) group, #P < 0.05 vs. saline + HS/T at 24 h.

At 24 h after HS/T, the percent of cells with T (CD3+, NK1.1‐) or B cell markers (B220) dropped significantly while the percent of PMN and macrophages significantly increased (Fig. 4D). The liver has a large number of macrophage lineage cells or Kupffer cells at baseline and macrophages rapidly infiltrate the liver after HS/T. As shown in Fig. 4E and F, the increase in PMN or macrophages induced by HS/T was not altered by prior NK1.1+ cell depletion. We confirmed the persistent near total deletion of NK and NKT cells in the liver at 24 h after HS/T by NK1.1 Ab pretreatment (data not shown). Thus, neither NK nor NKT cells appear to play a major role in PMN or macrophage influx into the liver in this model.

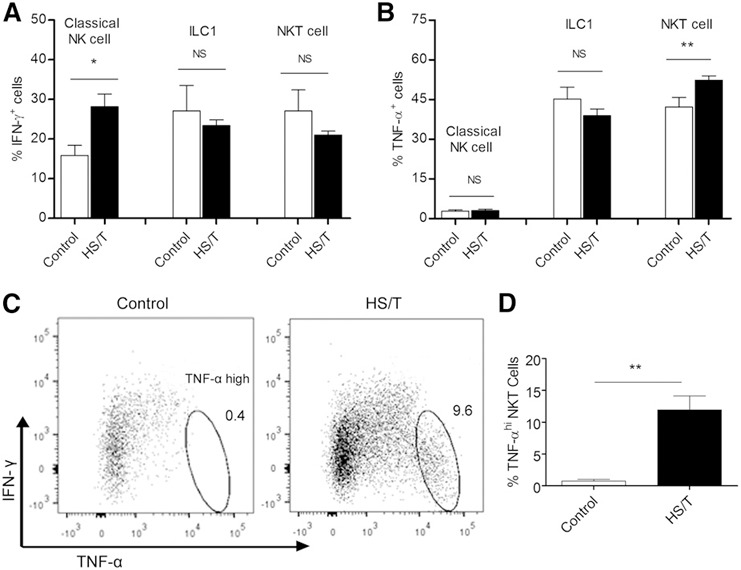

Intracellular IFN‐γ and TNF‐α expression by NK and NKT cell populations in the liver

To assess cytokine production by NK and NKT cell populations in liver at baseline and at 24 h after HS/T, liver nonparenchymal cells were isolated and exposed to PMA and ionomycin for 4 h in vitro. The cells were then fixed and permeabilized, and intracellular IFN‐γ and TNF were detected by immunofluorescence ( Fig. 5A and B ). HS/T led to an enhanced capacity for IFN‐γ production by classic NK cells and TNF‐α expression by NKT cells. As indicated in Fig. 5B, classic NK cells produced IFN‐γ but not a significant amount of TNF‐α. In contrast, ILC1 and NKT cells produced both IFN‐γ and TNF‐α, and those cell populations were multifunctional in that approximately one‐third of the cytokine‐positive cells produced both IFN‐γ and TNF‐α. Figure 5C and D shows the dot plots for IFN‐γ and TNF‐α production by the NKT cell population isolated from livers of control mice or mice subjected to HS/T. HS/T led to a marked increase in a population of TNF‐α–high NKT cells, which was completely absent in the control group. Those data suggest that liver classic NK cells have the capacity to produce more IFN‐γ and NKT cells to produce more TNF‐α after HS/T.

Figure 5.

Cytokine production by NK cell populations in the liver at 24 h after HS/T. (A) The proportion of the NK, ILC1, and NKT cells that stained positively for IFN‐γ. (B) The proportion of the NK, ILC1, and NKT cells that stained positively for TNF‐α. Cells harvested from the liver were stimulated in vitro with PMA and ionomycin for 4 h, fixed, permeabilized, and stained for IFN‐γ and TNF‐α. (C) Representative dot plots of IFN‐γ and TNF‐α staining by NKT cells prepared from control and HS/T mice, which reveals the presence of a TNF‐αbrightIFN‐γ− population that is present only in the HS/T mice. (D) The proportion of the NKT cells that was highly stained for TNF‐α and was negative for IFN‐γ. Data represent means ± sem; n = 3–5/group. *P < 0.05 vs. control group, **P < 0.01 vs. control group.

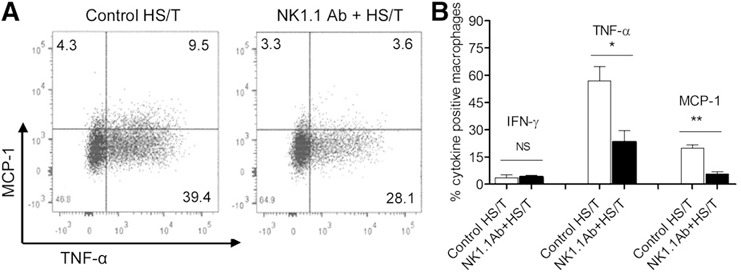

NK 1.1+ cell depletion reduces macrophage responses after HS/T

Klein et al. [26] proposed the existence of 2 types of Kupffer cells in liver: one was a resident population, with potent production of reactive oxygen species and phagocytic capacities; and the other a bone marrow–derived population with a potent capacity to produce type 1 cytokines, such as TNF‐α. The latter macrophage population has a central role in inflammatory responses in the liver. In the setting of infection, the resident Kupffer cells are rapidly lost, so they cannot directly contribute to immunity or tissue repair, but their necrotic death triggers the attraction and further differentiation of inflammatory monocytes [27]. We assessed how the deletion of NK1.1+ cells affected liver macrophage responses at 24 h after HS/T. Liver nonparenchymal cells were exposed to PMA and ionomycin for 4 h, fixed, and permeabilized. A dot plot for intracellular MCP‐1 and TNF‐α is shown in Fig. 6A and reveals that fewer MCP‐1+ and TNF‐α+ cells were seen in NK1.1‐depleted animals. The percentage of macrophages positive for IFN‐γ, TNF‐α, and MCP‐1 is shown in Fig. 6B and confirms that NK1.1+ cell depletion reduced macrophage capacity to express TNF‐α and MCP‐1. We hypothesized that IFN‐γ from NK cells may be one of the signals for macrophage MCP‐1 production. Dead Kupffer cells/macrophages have been shown to be a source of MCP‐1 release after HS/T [28]. Whether NK cells contribute to macrophage death in the liver is not known. Together, these data show that NK1.1+ cells enhance macrophage cytokine and chemokine production capacity after systemic injury and HS. These findings were consistent with other studies that showed NK cell‐derived IFN‐γ has a role in promoting M1 macrophage expansion [29, 30].

Figure 6.

Cytokine production by macrophages in the liver 24 h after HS/T. (A) Representative dot plots comparing TNF‐α and MCP‐1 staining in macrophages obtained from HS/T mice with or without NK1.1 depletion are depicted. (B) The proportions of macrophages staining for IFN‐γ, TNF‐α, and MCP‐1 in HS/T mice with or without NK1.1 depletion are depicted. Cells harvested from the liver were stimulated in vitro with PMA and ionomycin for 4 h, fixed, permeabilized, and stained for IFN‐γ, TNF‐α, and MCP‐1. Data represent means ± sem; n = 3–4/group. *P < 0.05 vs. control HS/T group, **P < 0.01 vs. control HS/T group.

This study was undertaken to determine the contribution of NK1.1+ cells to SIRS and end organ damage after HS/T. Using a murine model that combines hemorrhagic shock plus peripheral tissue trauma, we showed that NK cells are activated to produce INF‐γ and NKT cells to produce TNF‐α. This is associated with gut damage and a prolongation of ongoing liver damage after HS/T. We provide evidence that NK1.1+ cells promote inflammation and organ injury after HS/T by enhancing the macrophage response, leading to greater MCP‐1 production. These findings identify NK and NKT cell activation as an important step in the inflammatory response to systemic injury, contributing to liver and gut damage after HS/T.

AUTHORSHIP

S.C. performed research; collected, analyzed, and interpreted data; contributed to the experimental design; and wrote the manuscript. R.A.H. performed research; collected, analyzed, and interpreted data; and wrote the manuscript. M.S., J.M., P.L., and M.R. contributed to collection and analysis of data. A.J.D. performed pathologist scoring of the lung, liver, and gut. T.R.B. designed the research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material Files

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH/NIGMS Grant P50GM053789) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 81300053).

REFERENCES

- 1. Rhee, P. , Joseph, B. , Pandit, V. , Aziz, H. , Vercruysse, G. , Kulvatunyou, N. , Friese, R. S. (2014) Increasing trauma deaths in the United States. Ann. Surg. 260, 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lu, Q. , Xu, D. Z. , Sharpe, S. , Doucet, D. , Pisarenko, V. , Lee, M. , Deitch, E. A. (2011) The anatomic sites of disruption of the mucus layer directly correlate with areas of trauma/hemorrhagic shock‐induced gut injury. J. Trauma 70, 630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fishman, J. E. , Levy, G. , Alli, V. , Sheth, S. , Lu, Q. , Deitch, E. A. (2013) Oxidative modification of the intestinal mucus layer is a critical but unrecognized component of trauma hemorrhagic shock‐induced gut barrier failure. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 304, G57–G63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gill, R. , Ruan, X. , Menzel, C. L. , Namkoong, S. , Loughran, P. , Hackam, D. J. , Billiar, T. R. (2011) Systemic inflammation and liver injury following hemorrhagic shock and peripheral tissue trauma involve functional TLR9 signaling on bone marrow‐derived cells and parenchymal cells. Shock 35, 164–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Prince, J. M. , Levy, R. M. , Yang, R. , Mollen, K. P. , Fink, M. P. , Vodovotz, Y. , Billiar, T. R. (2006) Toll‐like receptor‐4 signaling mediates hepatic injury and systemic inflammation in hemorrhagic shock. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 202, 407–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cai, C. , Gill, R. , Eum, H. A. , Cao, Z. , Loughran, P. A. , Darwiche, S. , Edmonds, R. D. , Menzel, C. L. , Billiar, T. R. (2010) Complement factor 3 deficiency attenuates hemorrhagic shock‐related hepatic injury and systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 299, R1175–R1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cai, C. , Cao, Z. , Loughran, P. A. , Kim, S. , Darwiche, S. , Korff, S. , Billiar, T. R. (2011) Mast cells play a critical role in the systemic inflammatory response and end‐organ injury resulting from trauma. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 213, 604–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scott, M. J. , Hoth, J. J. , Gardner, S. A. , Peyton, J. C. , Cheadle, W. G. (2003) Natural killer cell activation primes macrophages to clear bacterial infection. Am. Surg. 69, 679–686, discussion 686–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barkhausen, T. , Frerker, C. , Pütz, C. , Pape, H. C. , Krettek, C. , van Griensven, M. (2008) Depletion of NK cells in a murine polytrauma model is associated with improved outcome and a modulation of the inflammatory response. Shock 30, 401–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhou, G. , Juang, S. W. , Kane, K. P. (2013) NK cells exacerbate the pathology of influenza virus infection in mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Quintin, J. , Voigt, J. , van der Voort, R. , Jacobsen, I. D. , Verschueren, I. , Hube, B. , Giamarellos‐Bourboulis, E. J. , van der Meer, J. W. , Joosten, L. A. , Kurzai, O. , Netea, M. G. (2014) Differential role of NK cells against Candida albicans infection in immunocompetent or immunocompromised mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 44, 2405–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Squires, J. E. , Shivakumar, P. , Mourya, R. , Bessho, K. , Walters, S. , Bezerra, J. A. (2015) Natural killer cells promote long‐term hepatobiliary inflammation in a low‐dose rotavirus model of experimental biliary atresia. PLoS One 10, e0127191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Christaki, E. , Diza, E. , Giamarellos‐Bourboulis, E. J. , Papadopoulou, N. , Pistiki, A. , Droggiti, D. I. , Georgitsi, M. , Machova, A. , Lambrelli, D. , Malisiovas, N. , Nikolaidis, P. , Opal, S. M. (2015) NK and NKT cell depletion alters the outcome of experimental pneumococcal pneumonia: relationship with regulation of interferon‐γ production. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 532717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bendelac, A. , Savage, P. B. , Teyton, L. (2007) The biology of NKT cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 297–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen, J. , Wei, Y. , He, J. , Cui, G. , Zhu, Y. , Lu, C. , Ding, Y. , Xue, R. , Bai, L. , Uede, T. , Li, L. , Diao, H. (2014) Natural killer T cells play a necessary role in modulating of immune‐mediated liver injury by gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 4, 7259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diao, H. , Kon, S. , Iwabuchi, K. , Kimura, C. , Morimoto, J. , Ito, D. , Segawa, T. , Maeda, M. , Hamuro, J. , Nakayama, T. , Taniguchi, M. , Yagita, H. , Van Kaer, L. , Onóe, K. , Denhardt, D. , Rittling, S. , Uede, T. (2004) Osteopontin as a mediator of NKT cell function in T cell‐mediated liver diseases. Immunity 21, 539–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cook, K. D. , Whitmire, J. K. (2013) The depletion of NK cells prevents T cell exhaustion to efficiently control disseminating virus infection. J. Immunol. 190, 641–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Darwiche, S. S. , Kobbe, P. , Pfeifer, R. , Kohut, L. , Pape, H. C. , Billiar, T. (2011) Pseudofracture: an acute peripheral tissue trauma model. J. Vis. Exp. (50):, 2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Menzel, C. L. , Sun, Q. , Loughran, P. A. , Pape, H. C. , Billiar, T. R. , Scott, M. J. (2011) Caspase‐1 is hepatoprotective during trauma and hemorrhagic shock by reducing liver injury and inflammation. Mol. Med. 17, 1031–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang, Y. , Zhang, J. , Korff, S. , Ayoob, F. , Vodovotz, Y. , Billiar, T. R. (2014) Delayed neutralization of interleukin 6 reduces organ injury, selectively suppresses inflammatory mediator, and partially normalizes immune dysfunction following trauma and hemorrhagic shock. Shock 42, 218–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mi, Q. , Constantine, G. , Ziraldo, C. , Solovyev, A. , Torres, A. , Namas, R. , Bentley, T. , Billiar, T. R. , Zamora, R. , Puyana, J. C. , Vodovotz, Y. (2011) A dynamic view of trauma/hemorrhage‐induced inflammation in mice: principal drivers and networks. PLoS One 6, e19424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ziraldo, C. , Vodovotz, Y. , Namas, R. A. , Almahmoud, K. , Tapias, V. , Mi, Q. , Barclay, D. , Jefferson, B. S. , Chen, G. , Billiar, T. R. , Zamora, R. (2013) Central role for MCP‐1/CCL2 in injury‐induced inflammation revealed by in vitro, in silico, and clinical studies. PLoS One 8, e79804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gao, B. , Radaeva, S. , Park, O. (2009) Liver natural killer and natural killer T cells: immunobiology and emerging roles in liver diseases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 86, 513–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peng, H. , Jiang, X. , Chen, Y. , Sojka, D. K. , Wei, H. , Gao, X. , Sun, R. , Yokoyama, W. M. , Tian, Z. (2013) Liver‐resident NK cells confer adaptive immunity in skin‐contact inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 1444–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tang, L. , Peng, H. , Zhou, J. , Chen, Y. , Wei, H. , Sun, R. , Yokoyama, W. M. , Tian, Z. (2016) Differential phenotypic and functional properties of liver‐resident NK cells and mucosal ILC1s. J. Autoimmun. 67, 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klein, I. , Cornejo, J. C. , Polakos, N. K. , John, B. , Wuensch, S. A. , Topham, D. J. , Pierce, R. H. , Crispe, I. N. (2007) Kupffer cell heterogeneity: functional properties of bone marrow derived and sessile hepatic macrophages. Blood 110, 4077–4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blériot, C. , Dupuis, T. , Jouvion, G. , Eberl, G. , Disson, O. , Lecuit, M. (2015) Liver‐resident macrophage necroptosis orchestrates type 1 microbicidal inflammation and type‐2‐mediated tissue repair during bacterial infection. Immunity 42, 145–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hildebrand, F. , Hubbard, W. J. , Choudhry, M. A. , Frink, M. , Pape, H. C. , Kunkel, S. L. , Chaudry, I. H. (2006) Kupffer cells and their mediators: the culprits in producing distant organ damage after trauma‐hemorrhage. Am. J. Pathol. 169, 784–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu, L. , Yue, Y. , Xiong, S. (2014) NK‐derived IFN‐γ/IL‐4 triggers the sexually disparate polarization of macrophages in CVB3‐induced myocarditis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 76, 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dungan, L. S. , McGuinness, N. C. , Boon, L. , Lynch, M. A. , Mills, K. H. (2014) Innate IFN‐γ promotes development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: a role for NK cells and M1 macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 44, 2903–2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material Files