Short abstract

A previously undefined role for IL‐27 in the optimal production of caspase‐1‐ and P2X7‐dependent LPS‐induced IL‐1β production in monocytic cells.

Keywords: lipopolysaccharide, inflammation, inflammasome, innate immunity, Toll‐like receptor

Abstract

IL‐27 bridges innate and adaptive immunity by modulating cytokine production from myeloid cells and regulating Th cell differentiation. During bacterial infection, TLR4 triggering by LPS induces IL‐27 production by monocytes and macrophages. We have previously shown that IL‐27 can prime monocytes for LPS responsiveness by enhancing TLR4 expression and intracellular signaling. If unregulated, this could result in damaging inflammation, whereas on the other hand, this may also provide greater responses by inflammatory processes induced in response to bacterial pathogens. A key process in fine‐tuning inflammatory responses is activation of the inflammasome, which ultimately results in IL‐1β production. Herein, we investigated the molecular mechanisms by which IL‐27 modulates LPS‐induced IL‐1β secretion in monocytes and macrophages. We found that when delivered simultaneously with LPS, IL‐27 augments activation of caspase‐1 and subsequent release of IL‐1β. Furthermore, we determined that IL‐27 primes cells for enhanced IL‐1β production by up‐regulating surface expression of TLR4 and P2X purinoceptor 7 (P2X7) for enhanced LPS and ATP signaling, respectively. These findings provide new evidence that IL‐27 plays an important role in the proinflammatory capacity of monocytes and macrophages via enhancing IL‐1β secretion levels triggered by dual LPS–ATP stimulation.

Abbreviations

- Ac‐YVAD‐CHO

acetyl‐Tyr‐Val‐Ala‐Asp‐aldehyde

- ASC

apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein

- BMDM

bone marrow‐derived macrophage

- CD14–THP‐1

THP‐1 cells transfected with cluster of differentiation 14‐expressing cDNA plasmids

- CRID3

cytokine release inhibitory drug 3

- DSHB

Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank

- EBI3

EBV‐induced gene 3

- FMK

benzyloxycarbonyl‐Trp‐Glu(OMe)‐His‐Asp(OMe)‐fluoromethylketone

- IL‐27Ra−/−

IL‐27Rα‐deficient mice

- MD2

myeloid differentiation factor 2

- NLRC4

nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain‐like receptor family caspase activation and recruitment domain‐containing 4

- NLRP3

nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain‐like receptor family pyrin domain‐containing 3

- p28

IL‐27p28

- WT

wild‐type

Introduction

IL‐27 is a heterodimeric cytokine composed of p28 and EBI3 subunits [1, 2, 3–4]. IL‐27R is also heterodimeric, composed of IL‐27Rα (WSX‐1), unique for binding IL‐27, and gp130, a signaling subunit shared with IL‐6 [5, 6]. In monocytes and macrophages, IL‐27 activates JAK/STAT signaling via STAT1 [6] and STAT3 [7, 8]. IL‐27‐mediated effects are also modulated by the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 protein, which negatively regulates STAT3 activation [9, 10–11]. IL‐27 participates in Th cell differentiation by supporting Th1 cell development and IFN‐γ production and by blocking Th17 development [4, 12]. Recent investigations have sparked interest in IL‐27 as an inducer of myriad proinflammatory responses. Indeed, evidence supports a role for IL‐27 in the activation of monocytic cells, including up‐regulation of proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine production [8, 13, 14–15]. Inflammatory agents, such as LPS, induce the production of IL‐27 subunits, p28 and EBI3, which are predominantly expressed by monocytes/macrophages and dendritic cells to form the bioactive IL‐27 cytokine [4, 16].

During inflammation, monocytes and macrophages secrete high levels of proinflammatory cytokines in response to bacterial components recognized by TLRs. Of these responses, TLR4 signaling, triggered by LPS from Gram‐negative bacteria, is a key mediator of inflammatory cytokine production, including secretion of IL‐27 [1, 17]. Critical inflammatory processes, triggered by LPS, include inflammasome activation, resulting in caspase‐1‐dependent cleavage of pro‐IL‐1β to produce active IL‐1β [18, 19]. Both inflammasome formation and subsequent IL‐1β production are induced by TLR4 engagement [20]. IL‐1β activates and recruits immune cells to drive inflammation; however, uncontrolled IL‐1β expression causes excessive inflammation and tissue damage [21]. Of the inflammasomes identified, the NLRP3 and NLRC4 inflammasomes are well characterized [22]. NLRP3 or NLRC4 can complex with ASC and procaspase‐1 to induce IL‐1β cleavage and secretion [18, 22, 23, 24–25]. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome can be modulated by two signals: Signal 1, from LPS/TLR4 ligation, up‐regulates expression of inflammasome components (NLRP3, ASC, procaspase‐1), whereas Signal 2, provided by ATP, nigericin, alum crystals, or other TLR agonists, activates the inflammasome by cleavage of procaspase‐1 into active caspase‐1 [18, 26, 27–28]. Upon ligation of ATP with its receptor P2X purinoceptor 7 (P2X7), pannexin‐1 hemichannel pore formation occurs, resulting in potassium efflux from the cell [29, 30, 31–32]. The change in ion gradient leads to inflammasome oligomerization, mediating autolytic cleavage of caspase‐1 and consequent cleavage of pro‐IL‐1β for release of biologically active IL‐1β [33, 34].

Our previous work demonstrated that IL‐27 induces a proinflammatory cytokine profile in nonactivated (resting) primary human monocytes and can enhance LPS‐mediated proinflammatory responses via up‐regulation of TLR4 expression [8, 13]. In this study, we demonstrate a key role for IL‐27 in LPS‐induced IL‐1β production, where experiments with murine BMDMs deficient for the IL‐27R show reduced IL‐1β production in response to stimulation with LPS followed by ATP. Furthermore, we demonstrate that simultaneous stimulation of IL‐27 and LPS, followed by ATP treatment, augments NLRP3‐ and P2X7‐dependent IL‐1β secretion in human monocytic cells. Taken together, our data show that IL‐27 is required for optimal LPS‐induced IL‐1β production and that exogenous IL‐27 further enhances the LPS response, highlighting a novel role for IL‐27 in the regulation of innate immune responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and reagents

CD14–THP‐1 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Richard Ulevitch (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA). Cells were cultured in RPMI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), supplemented with 10% FBS (GE Healthcare Life Sciences Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA) and G418 (BioShop Canada, Burlington, Ontario, Canada). Recombinant human and murine IL‐27 was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA) and eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA), respectively. LPS from Escherichia coli 0111:B4 was purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). ATP was purchased from BioShop Canada. Nigericin and alum crystals were purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA, USA). FMK, glybenclamide, and CRID3 sodium salt (MCC 950) were purchased from R&D Systems. Probenecid was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). Molecular Probes YO‐PRO‐1 iodide (491/509) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Cell death in the presence of inhibitors was equivalent to cells cultured in medium alone (≤10%), as measured by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry (Sigma‐Aldrich).

BMDM isolation

Murine BMDMs were cultured as described in detail elsewhere [35]. IL‐27Ra−/− mice were backcrossed onto C57BL/6 mice, and C57BL/6 mice were used as controls [36, 37]. In brief, femurs and tibias from WT C57BL/6 and IL‐27Ra−/− mice were collected, and the marrow was flushed with PBS. RBCs were lysed with a lysis buffer (1.66% w/v ammonium chloride) for 5 min. After several washing steps with PBS, the cells were cultured in 6‐well tissue‐culture plates (3–5 × 106 cells/well) in conditioned medium, consisting of RPMI containing 10% FBS and 20% of L929 supernatant as a source of M‐CSF. After 3 d, the nonadherent cells were removed, and fresh medium was added. The medium was changed every 2 d, and BMDM cells were harvested on d 7. BMDMs were ≥95% pure, as determined by F4/80 staining and flow cytometry.

Monocyte isolation

Enriched monocytes were isolated from whole blood of healthy donors obtained under Queen's University Research Ethics Board approval. Whole‐blood samples were processed with the RosetteSep Human Monocyte Enrichment Cocktail (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), as described by the manufacturer's instructions. Enriched blood was overlaid on Lympholyte Human Cell Separation Media (Cedarlane, Burlington, ON, Canada), processed by density centrifugation for 20 min at 800 g. Cells were washed twice with PBS plus 10 mM EDTA and 2% FBS and then resuspended in RPMI + 10% FBS at 1 × 106 cells/ml. Monocyte populations were ≥95% pure, as determined by CD14 staining and flow cytometry.

ELISA

Culture supernatants were used to quantify cytokine expression, according to the manufacturer's instructions for IL‐1β (Ready‐SET‐Go! kit; eBioscience). Absorbance was measured with the BioTek ELx800 Microplate Reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 450 nm. Data are representative of the average of duplicate wells ± sd from 6 independent experiments.

Caspase‐1 bioluminescent protease assay

Culture supernatants were used to quantify caspase‐1 activity, according to the manufacturer's instructions for the Caspase‐Glo 1 assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The Caspase‐Glo Z‐WEHD‐aminoluciferin substrate and luciferase reagent were added to culture supernatants, whereby caspase‐1‐induced cleavage of the substrate releases the proluciferin for luciferase reaction, chemically represented by emitted luminescence at 560 nm. Luciferase activity was measured with the GloMax 96 Microplate Luminometer (Promega). Data are representative of the average of duplicate wells ± sd from 3 independent experiments.

Western blotting

Cell pellets were lysed with lysis buffer (1 M HEPES, 0.5 M NaF, 0.5 M EGTA, 2.5 M NaCl, 1 M MgCl2, 10% glyercol, 1% Triton X‐100) with PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Protein concentrations were measured using the Bradford assay (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Lysates (50–100 μg protein) were separated on 8–10% polyacrylamide SDS‐PAGE and then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (BioRad Laboratories). Membranes were probed with anti‐IL‐1β, anti‐caspase‐1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti‐NLRP3 and anti‐pannexin‐1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), and anti‐β‐tubulin (Sigma‐Aldrich) as a loading control. Secondary antibodies used include goat‐anti rabbit IgG‐HRP and goat‐anti mouse IgG‐HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immunoblots were visualized using Clarity ECL (BioRad Laboratories) on an Alpha Innotech HD2 imager using HD2 Imaging software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Blots are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

Flow cytometry

For surface staining, cells were resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS + 0.01% sodium azide + 2% FBS) and incubated with anti‐human TLR4 AlexaFluor 488 (eBioscience), anti‐human MD2 (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), anti‐human CD14 biotin (eBioscience), or anti‐human P2X7. Anti‐P2X7 was deposited to the DSHB (DSHB Hybridoma Product P2X7‐L4), Iowa City, IA, USA by Ben Gu (Florey Institute of Neuroscience & Mental Health, Victoria, AU). Cells were stained with secondary antibodies: F(ab′)2 anti‐rabbit IgG‐PE (eBioscience), streptavidin AlexaFluor 610‐R‐PE (Thermo Fisher Scientific), goat anti‐mouse IgG (H+L) R‐PE (Biotium, Fremont, CA, USA), or isotype controls: mouse IgG1‐FITC and mouse IgG2b‐PE (eBioscience). Data were acquired with the Epics XL‐MCL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and analyzed using FlowJo software, version 10.0.7r2.

YO‐PRO‐1 iodide assay

Culture cells were incubated with ATP (5 mM) and YO‐PRO‐1 iodide (1 μM) in RPMI medium simultaneously at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 15 min to allow for dye uptake. Cells were washed and resuspended in FACS buffer. Data were acquired with the Epics XL‐MCL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and analyzed using FlowJo software, version 10.0.7r2.

Statistical analysis

Significance was calculated on GraphPad Prism 6 using an unpaired, 2‐tailed t test over multiple repeated experiments between specified groups or Wilcoxon signed‐rank test for comparisons with medium fold change given a hypothetical mean of 1.0.

RESULTS

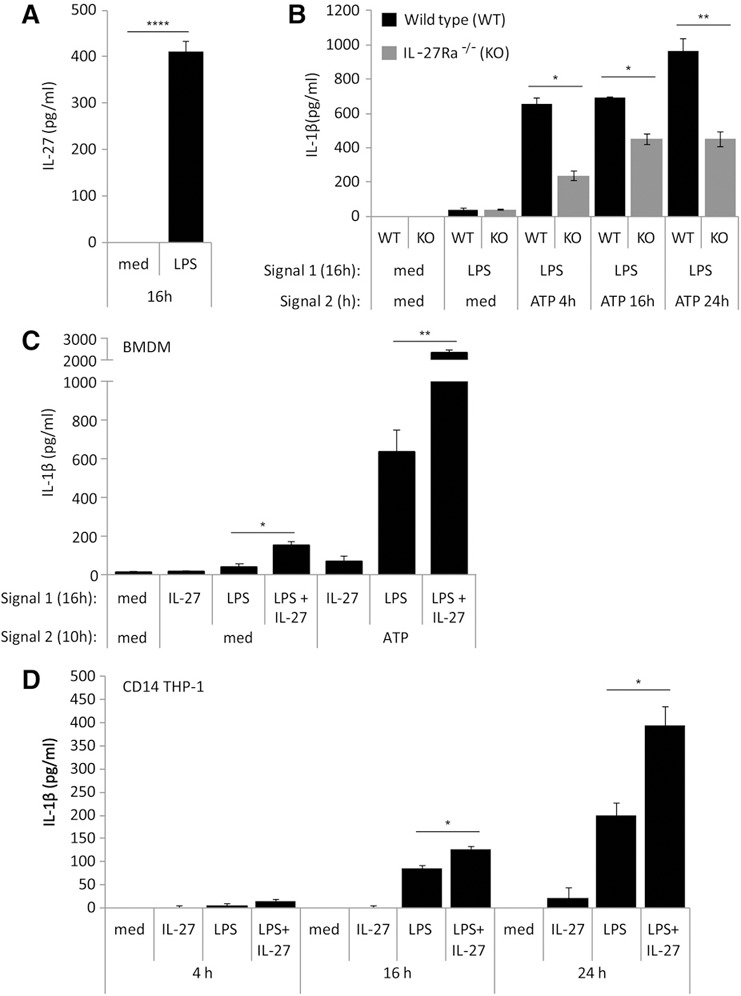

IL‐27 is required for optimal IL‐1β secretion

Previous work by others established that LPS stimulation induces IL‐27 expression [4, 16], and we demonstrated that IL‐27 can enhance LPS responses in human monocytes [13]. Thus, we reasoned that IL‐27 may play a role in LPS‐mediated IL‐1β production. To ascertain if endogenously produced IL‐27 is involved in LPS‐mediated IL‐1β induction, we used BMDMs isolated from WT or IL‐27Ra−/− as our model system. To demonstrate that BMDMs produce IL‐27 in response to LPS, WT BMDMs were treated with LPS for 16 h. Under these conditions, BMDMs produced significant levels of IL‐27 following LPS stimulation ( Fig. 1A ). Furthermore, to investigate the potential requirement for endogenously produced IL‐27 in response to LPS in IL‐1β production, BMDMs from WT and IL‐27Ra−/− mice were treated with LPS (Signal 1), followed by ATP treatment (Signal 2) at various time points. In both WT and IL‐27Ra−/− cells, LPS‐induced IL‐1β production was detected at relatively low levels (Fig. 1B). LPS‐induced IL‐27 production was observed in both cell types (data not shown). In cells exposed to LPS and subsequently treated with ATP, we observed markedly enhanced IL‐1β production. Most striking was the observation that ATP‐induced IL‐1β secretion was significantly reduced in IL‐27Ra−/− BMDM compared with WT at all time‐points tested (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

IL‐27 is required for optimal LPS‐induced IL‐1β production in murine BMDM and human monocytic cells. (A) WT BMDM cells were incubated in the presence of LPS (100 ng/ml) for 16 h. Secreted levels of murine IL‐27 were measured by ELISA in cell‐free supernatants. (B) WT and IL‐27Ra−/− [knockout (KO)] BMDMs were incubated in the presence of Signal 1: LPS (100 ng/ml), IL‐27 (50 ng/ml), or LPS plus IL‐27 for 16 h. Cells were then washed and resuspended in new media and exposed to Signal 2: ATP (5 mM) for 4, 10, and 24 h. Secreted levels of murine IL‐1β were measured by ELISA in cell‐free supernatants. (C) WT BMDM cells were incubated in the presence of Signal 1: LPS (100 ng/ml), murine IL‐27 (50 ng/ml), or LPS plus IL‐27 for 16 h. Cells were then washed and resuspended in new media and exposed to Signal 2: ATP (5 mM) for 10 h. Secreted levels of murine IL‐1β were measured by ELISA in cell‐free supernatants. (D) CD14–THP‐1 cells were incubated in the presence of LPS (100 ng/ml), IL‐27 (100 ng/ml), or LPS plus IL‐27 for 4, 16, and 24 h. Secreted levels of IL‐1β were measured by ELISA in cell‐free supernatants. Data are representative of BMDMs derived from six WT mice and six IL‐27Ra−/− mice or at least three CD14–THP‐1‐independent experiments. Error bars indicate sd of technical replicates. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ****P ≤ 0.0001, unpaired, 2‐tailed t test.

To examine the effects of IL‐27 in LPS‐induced IL‐1β production, WT cells were treated with LPS alone, IL‐27 alone, or LPS and IL‐27 simultaneously for 16 h as Signal 1, followed by treatment, with or without ATP (Signal 2), for 10 h and subsequently tested for IL‐1β secretion. We observed that LPS alone was able to induce a moderate level of IL‐1β production. However, in the presence of LPS and IL‐27 together, IL‐1β production was significantly higher (Fig. 1C). In cells given LPS (Signal 1) and ATP (Signal 2), ATP‐induced IL‐1β production was higher compared with cells treated with LPS alone, as expected (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, simultaneous treatment of cells with LPS and IL‐27 resulted in a striking increase in ATP‐induced IL‐1β secretion compared with cells treated with only LPS and ATP (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that BMDMs produce greater amounts of IL‐1β in response to LPS and IL‐27 when given simultaneously, indicating a potential synergistic role for LPS and IL‐27 in inducing IL‐1β production.

To investigate if IL‐27 could modulate IL‐1β production in human cells, we treated CD14–THP‐1 cells with LPS, IL‐27, or LPS plus IL‐27 for 4, 16, and 24 h. Control cells were cultured in medium alone (med) for 4, 16, or 24 h, and resulting IL‐1β secretion was measured by ELISA in cell‐free supernatants. Results showed that LPS alone induced IL‐1β expression, whereas IL‐27 alone did not. Similar to our observations in BMDMs, a statistically significant increase in IL‐1β expression was observed in cells treated simultaneously with LPS and IL‐27 at 16 and 24 h compared with LPS alone (Fig. 1D). This demonstrates that exogenously added IL‐27 synergistically enhances LPS‐induced IL‐1β production in CD14–THP‐1 cells.

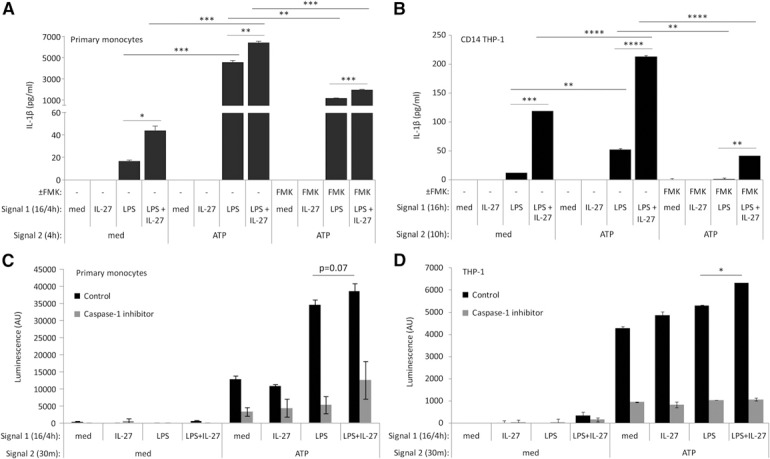

IL‐27 enhances caspase‐1‐dependent LPS/ATP‐mediated IL‐1β production

As inflammasome formation is initiated in human monocytic cells by a secondary signal (Signal 2) provided by ATP [20, 38], we examined the role for IL‐27 in ATP‐dependent, LPS‐induced IL‐1β expression. As we described previously [13], IL‐27 pretreatment for 16 h optimally enhances LPS signaling in primary monocytes; therefore, we maintained the 16 h treatment with IL‐27 throughout all experiments. To optimize LPS/ATP treatment times, we performed time course analyses (data not shown). From this, we observed that in primary monocytes, LPS addition in the last 4 h of the 16 h IL‐27 treatment, followed by a 4 h ATP treatment, resulted in maximal induction of IL‐1β. In contrast, CD14–THP‐1 cells exhibited maximal IL‐1β production after 16 h LPS and IL‐27 and 10 h ATP. Thus, primary monocytes and CD14–THP‐1 were treated accordingly. As expected, in cells given medium (med; Signal 1) followed by ATP (Signal 2) no IL‐1β was detected ( Fig. 2A and B ). However, we observed significant IL‐1β expression in response to ATP in LPS‐treated cells. Consistent with the data shown in Fig. 1D, cells pretreated with IL‐27 alone showed no significant IL‐1β induction, even with ATP stimulation (Fig. 2A and B). Despite this, we observed a striking increase in IL‐1β expression in response to ATP in both cell types treated with LPS plus IL‐27 compared with cells that received LPS alone (Fig. 2A and B). In cells that received LPS plus IL‐27 as Signal 1, followed by medium, IL‐1β was detected, likely as a result of the ability of LPS plus IL‐27 to induce IL‐1β in the absence of exogenously added ATP, as observed in Fig. 1D. Taken together, these data demonstrate that stimulation of human monocytic cells with LPS and IL‐27 followed by ATP results in enhanced inflammasome activation compared with LPS/ATP alone.

Figure 2.

IL‐27 cotreatment with LPS enhances IL‐1β production in primary human monocytes and CD14–THP‐1 cells. (A) Primary human monocytes were incubated in the presence of Signal 1: LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 h, IL‐27 (100 ng/ml) for 16 h, or IL‐27 for 16 h plus LPS for the final 4 h, with or without FMK (20 μM) for 16 h. Cells were washed and resuspended in new media and then exposed to Signal 2: ATP (5 mM) for 4 h, with or without FMK (20 μM). Secreted levels of IL‐1β were measured by ELISA in cell‐free supernatants. (B) CD14–THP‐1 cells were incubated in the presence of Signal 1: LPS (100 ng/ml), IL‐27 (100 ng/ml), or LPS plus IL‐27 for 16 h, with or without FMK (20 μM). Cells were washed and resuspended in new media and then exposed to Signal 2: ATP (5 mM) for 10 h, with or without FMK (20 μM). Secreted levels of IL‐1β were measured by ELISA in cell‐free supernatants. (C) Primary human monocytes and (D) THP‐1 cells were incubated in the presence of Signal 1: LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 h, IL‐27 (100 ng/ml) for 16 h, or IL‐27 for 16 h plus LPS for the final 4 h. Cells were then exposed to Signal 2: ATP (5 mM) for 30 min. Ac‐YVAD‐CHO caspase‐1 inhibitor was used as a control, per the manufacturer's instructions. Caspase‐1 activity was measured by bioluminescent luciferase activity in cell‐free supernatants. Data are representative of at least four replicate experiments. Error bars indicate sd of replicate sets. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001, unpaired, 2‐tailed t test.

As procaspase‐1 cleavage and caspase‐1 activity are required for IL‐1β production, the caspase‐1 inhibitor FMK was used to confirm the requirement for caspase‐1 in our model [39]. Cells were treated with LPS, IL‐27, or IL‐27 for 16 h, with LPS in the final 4 h (primary monocytes), or LPS, IL‐27, or LPS and IL‐27 for 16 h (CD14–THP‐1), followed by ATP for an additional 4 (primary monocytes) or 10 h (CD14–THP‐1) in the presence or absence of FMK (20 μM). Both primary monocytes and CD14–THP‐1 cells showed significantly decreased IL‐1β production in the presence of FMK (Fig. 2A and B). This shows a requirement for caspase‐1 in ATP‐induced inflammasome activation upon treatment with LPS alone or LPS plus IL‐27 as Signal 1.

Given that IL‐1β production requires caspase‐1, we investigated whether IL‐27 may impact the activity of this protease. Therefore, we examined how dual stimulation with LPS and IL‐27 impacts activity of caspase‐1 by using a caspase‐1 activity assay. We initially performed this assay in CD14–THP‐1 cells; however these cells gave an unexpectedly high baseline reading (data not shown). Therefore, we performed this assay in the parental THP‐1 cell line, as well as in primary human monocytes. Primary monocytes (Fig. 2C) and THP‐1 cells (Fig. 2D) were treated with IL‐27 or left untreated (med) for 16 h, with LPS added during the last 4 h of these treatments, and then followed by ATP for 30 min in both cell types for optimal detection of caspase‐1 activity. Caspase‐1 activity was then quantified in cell‐free supernatants. As expected, caspase‐1 activity did not exceed baseline levels in cells that received the caspase‐1 inhibitor, Ac‐YVAD‐CHO (Fig. 2C and D; gray bars). After ATP stimulation, LPS plus IL‐27‐treated THP‐1 cells exhibited significantly higher caspase‐1 activity compared with LPS alone (Fig. 2C and D; black bars). In cells treated with IL‐27 alone, no significantly different ATP‐induced caspase‐1 activity was observed compared with medium controls for Signal 1. Similar trends were observed in primary human monocytes and THP‐1 cells, whereby LPS plus IL‐27 treatment induced greater caspase‐1 activity compared with LPS treatment alone; however, these differences did not reach statistical significance in primary monocytes (Fig. 2C and D; black bars).

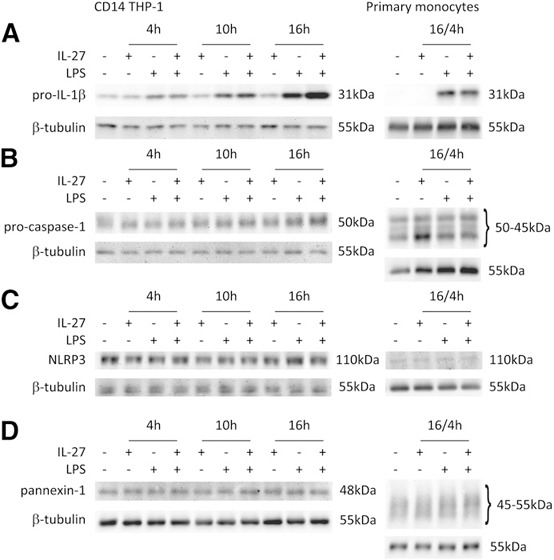

IL‐27 induces elevated LPS‐induced pro‐IL‐1β and procaspase‐1 in CD14–THP‐1 cells but not primary human monocytes

To investigate the mechanism used by IL‐27 to enhance LPS‐induced IL‐1β production protein levels of pro‐IL‐1β, procaspase‐1, NLRP3, as well as the ion hemichannel opened by ATP stimulation, pannexin‐1, were measured by Western blotting. CD14–THP‐1 was stimulated with LPS, IL‐27, or LPS plus IL‐27 for 4, 10, and 16 h, whereas primary human monocytes were treated with or without IL‐27 for 16 h, with or without LPS for 4 h. Levels of pro‐IL‐1β and procaspase‐1 were elevated in CD14–THP‐1 cells stimulated for 16 h with LPS plus IL‐27 compared with LPS alone ( Fig. 3A and B ; left). As expected, pro‐IL‐1β expression was enhanced by LPS stimulation in primary human monocytes. Surprisingly, primary monocytes stimulated with LPS plus IL‐27 did not show notable differences in pro‐IL‐1β or procaspase‐1 levels compared with LPS alone (Fig. 3A and B; right). However, there was a notable increase in the caspase‐1 intermediate form (45 kDa band) upon IL‐27 stimulation alone compared with LPS alone or LPS plus IL‐27 stimulation in primary human monocytes (Fig. 3B; right) A more moderate effect of IL‐27 alone on procaspase‐1 expression levels in CD14–THP‐1 cells was also observed. Levels of NLRP3 and pannexin‐1 in both CD14–THP‐1 cells and primary human monocytes showed no distinguishable differences among unstimulated, LPS‐, IL‐27‐, or LPS plus IL‐27‐stimulated groups (Fig. 3C and D). Of note, glycosylated pannexin‐1 was observed in primary monocytes, as confirmed by endoglycosidase H treatment of cell extracts (data not shown). Thus, we detected multiple bands in monocyte extracts compared with that obtained from CD14–THP‐1 cells (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these data suggest that in CD14–THP‐1 cells, IL‐27‐modulated LPS‐induced IL‐1β secretion is potentiated by up‐regulation of pro‐IL‐1β and procaspase‐1 expression; however, in primary monocytes, a different mechanism may be at play.

Figure 3.

IL‐27 costimulation up‐regulates LPS‐induced pro‐IL‐1β and procaspase‐1 in CD14–THP‐1 cells but not in primary human monocytes. CD14–THP‐1 cells were treated with IL‐27 (100 ng/ml) and/or LPS (100 ng/ml), as specified, for 4, 10, or 16 h. Primary monocytes were treated with IL‐27 (100 ng/ml) for 16 h with the addition of LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 h. Levels of pro‐IL‐1β (A), procaspase‐1 (B), NLRP3 (C), and pannexin‐1 (D) were measured in whole‐cell lysates by Western blotting. Blots were stripped and reprobed with β‐tubulin as a loading control. Blots are representative of at least 3 independent stimulations. Adjustments of brightness/contrast were applied to individual entire images.

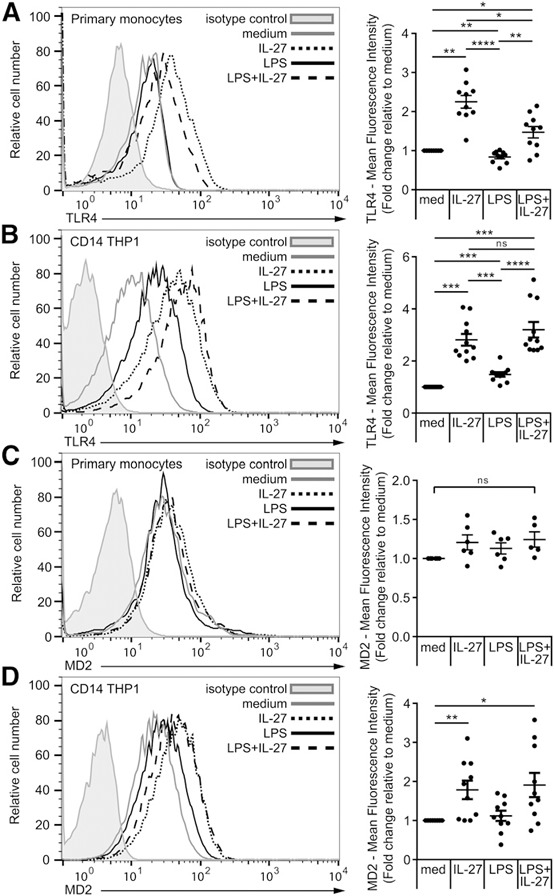

IL‐27 enhances TLR4 and MD2 expression but does not affect CD14 expression

As levels of the LPS‐binding partners, TLR4, MD2, and CD14, may contribute to enhanced LPS responsiveness and inflammasome induction, we assessed whether dual stimulation with IL‐27 and LPS affected surface levels of these proteins. Primary human monocytes were stimulated with IL‐27 for 16 h and LPS for the last 4 h ( Fig. 4A ), whereas CD14–THP‐1 cells were stimulated with LPS alone, IL‐27 alone, or LPS plus IL‐27 for 16 h (Fig. 4B). As documented previously [13], treatment with IL‐27 alone significantly up‐regulated TLR4 expression in both cell types, and likewise, LPS plus IL‐27 also induced significantly greater TLR4 expression compared with LPS alone (Fig. 4A and B). Primary human monocytes showed a very modest increase in MD2 expression in LPS plus IL‐27‐stimulated cells compared with medium control; however, these differences did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4C), whereas MD2 showed increased levels upon IL‐27 or LPS plus IL‐27 stimulation in CD14–THP‐1 compared with medium controls (Fig. 4D). CD14 showed no consistent changes across the different conditions (data not shown). Taken together, these data indicate that IL‐27‐induced TLR4 and MD2 expression likely contributes to enhanced LPS responsiveness in human monocytic cells.

Figure 4.

IL‐27 enhances LPS‐induced inflammasome activation via up‐regulation of TLR4 and MD2 in primary human monocytes and CD14–THP‐1 cells. Primary human monocytes were incubated in the presence of Signal 1: LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 h, IL‐27 (100 ng/ml) for 16 h, or IL‐27 for 16 h plus LPS for the final 4 h (A and C). CD14–THP‐1 cells were incubated in the presence of LPS (100 ng/ml), IL‐27 (100 ng/ml), or LPS plus IL‐27 for 16 h (B and D). Cells were then stained for TLR4 (A and B) or MD2 (C and D). All data sets were measured using flow cytometry and analyzed using FlowJo software, version 10.0.7r2. Cells were gated for live cells and then CD14+ monocytic cells. Lines indicate stained cells, and filled histograms represent isotype controls. Histograms are representative of six replicate experiments. Fold increase was calculated relative to medium per individual experiment and plotted for each experiment as the average fold increase. Error bars indicate se of all replicates. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant, Wilcoxon signed‐rank test used for analysis relative to medium given a hypothetical value of 1.0 and unpaired, 2‐tailed t test used for analysis between other groups.

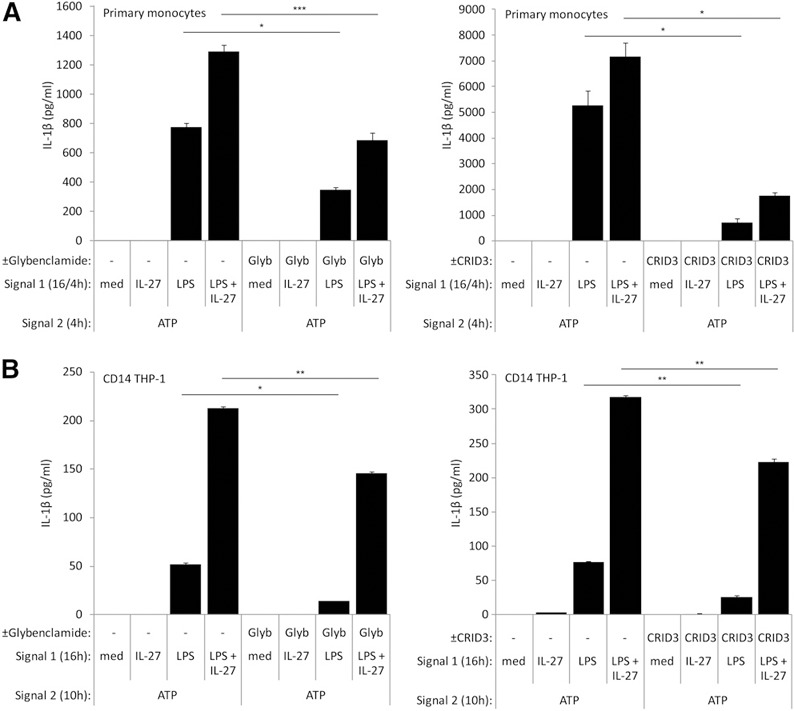

IL‐27‐enhanced, LPS‐mediated IL‐1β production requires NLRP3

To confirm that the NLRP3 inflammasome is required for IL‐1β production in our model, we treated cells with glybenclamide, which blocks the ATP‐sensitive potassium channels required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation [29, 40], or CRID3 sodium salt (MCC 950), which inhibits ASC oligomerization and NLRP3 inflammasome formation [41]. CD14–THP‐1 cells and primary human monocytes were incubated in the presence and absence of the NLRP3 inhibitors with Signal 1 (LPS + IL‐27), followed by Signal 2 (ATP) treatment. Glybenclamide and CRID3 sodium salt significantly inhibited ATP‐induced IL‐1β production in cells treated with LPS or LPS plus IL‐27 to levels observed with the Signal 2 control (med) in CD14–THP‐1 cells ( Fig. 5A ). Likewise, in primary monocytes, LPS and LPS plus IL‐27‐primed monocytes showed significantly lower IL‐1β production upon the addition of glybenclamide or CRID3 sodium salt compared with cells without inhibitors (Fig. 5B). These data suggest that NLRP3‐induced potassium efflux is required for LPS plus IL‐27‐induced IL‐1β production.

Figure 5.

Optimal inflammasome activation is dependent on NLRP3‐induced potassium efflux in CD14–THP‐1 cells and primary human monocytes. (A) Primary human monocytes were incubated in the presence of glybenclamide (Glyb; 50 μM; left) or CRID3 sodium salt (200 nM; right) for 16 h, along with Signal 1: LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 h, IL‐27 (100 ng/ml) for 16 h, or IL‐27 for 16 h plus LPS for the final 4 h. Cells were washed and resuspended in new media and then exposed to glybenclamide (50 μM) for 4 h (left) or CRID3 sodium salt (200 nM) for 4 h (right), along with Signal 2: ATP (5 mM) for 4 h. Secreted levels of IL‐1β were measured by ELISA in cell‐free supernatants. (B) CD14–THP‐1 cells were incubated in the presence of glybenclamide (50 μM; left) or CRID3 sodium salt (200 nM; right) for 16 h, along with Signal 1: LPS (100 ng/ml), IL‐27 (100 ng/ml), or LPS plus IL‐27 for 16 h. Cells were washed and resuspended in new media and then exposed to glybenclamide (50 μM; left) or CRID3 sodium salt (200 nM; right) for 10 h, along with Signal 2: ATP (5 mM) and for 10 h. Secreted levels of IL‐1β were measured by ELISA in cell‐free supernatants. Data are representative of six replicate experiments. Error bars indicate sd of technical replicates. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001, unpaired, 2‐tailed t test.

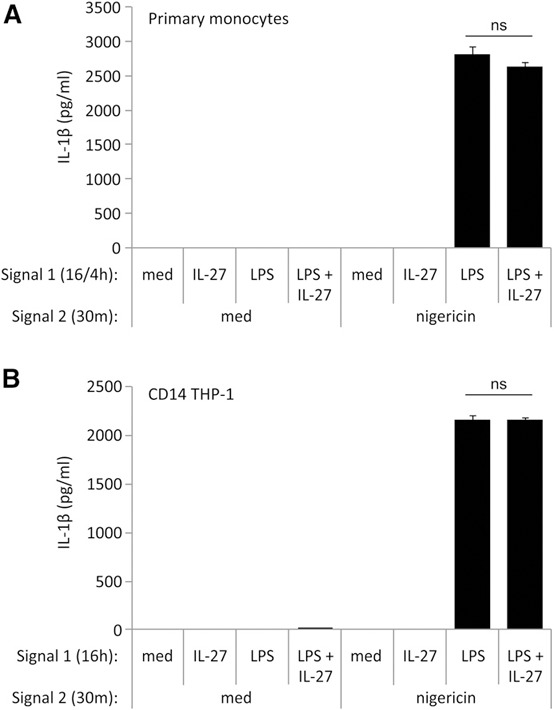

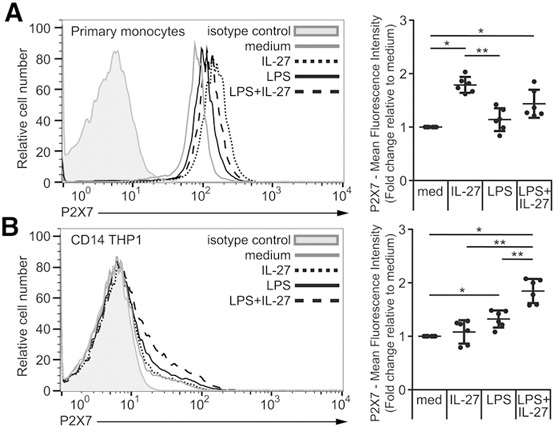

IL‐27‐enhanced IL‐1β production is dependent on the P2X7 receptor and pannexin‐1‐activity

As inflammasome activity can be stimulated by multiple mechanisms, we investigated if IL‐27 could mediate NLRP3 inflammasome activity induced by other agonists. Therefore, we examined the impact of IL‐27 treatment on nigericin‐mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activity [42]. We treated primary human monocytes with IL‐27 for 16 h, LPS for the last 4 h, and CD14–THP‐1 cells with LPS, IL‐27, or both LPS plus IL‐27 for 16 h, and both cell types were then stimulated with nigericin for an additional 30 min [38, 43]. As expected, stimulation of cells with LPS followed by nigericin induced IL‐1β production ( Fig. 6A and B ). Interestingly, IL‐27 pretreatment with LPS followed by nigericin did not show any significant difference compared with LPS and nigericin alone (Fig. 6A and B). This demonstrates that whereas the NLRP3 inflammasome is responsible for IL‐1β induction in our model, IL‐27 may be affecting a mechanism upstream of NLRP3 activation. Therefore, we decided to investigate the impact of IL‐27 on expression and function of the ATP receptor, P2X7. Primary human monocytes were stimulated with IL‐27 for 16 h plus LPS for the last 4 h, whereas CD14–THP‐1 cells were stimulated with LPS alone, IL‐27 alone, or LPS plus IL‐27 for 16 h. Expression of P2X7 was analyzed by flow cytometry ( Fig. 7A and B ). Both primary human monocytes and CD14–THP‐1 cells showed significantly greater P2X7 surface expression in LPS plus IL‐27 compared with cells stimulated with medium alone (Fig. 7A and B). In primary monocytes, IL‐27 alone induced significantly greater P2X7 expression compared with medium or LPS alone (Fig. 7A), whereas CD14–THP‐1 cells showed enhanced P2X7 surface expression upon both LPS and LPS plus IL‐27 stimulation (Fig. 7B). These data indicate that costimulation of LPS and IL‐27 up‐regulates the ATP receptor in human monocytic cells—a possible novel mechanism used by IL‐27 to enhance LPS‐induced IL‐1β production.

Figure 6.

Nigericin‐induced IL‐1β production is unaffected by IL‐27 treatment. (A) Primary human monocytes were incubated in the presence of Signal 1: LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 h, IL‐27 (100 ng/ml) for 16 h, or IL‐27 for 16 h plus LPS for the final 4 h. (B) CD14–THP‐1 cells were incubated in the presence of Signal 1: LPS (100 ng/ml), IL‐27 (100 ng/ml), or LPS plus IL‐27 for 16 h. Cells were washed and resuspended in fresh media and exposed to Signal 2: nigericin (20 μM) for 20 min. Secreted levels of IL‐1β were measured by ELISA in cell‐free supernatants. Data are representative of six replicate experiments. Error bars indicate sd of technical replicates.

Figure 7.

IL‐27 up‐regulates ATP receptor P2X7 in primary human monocytes and CD14–THP‐1 cells. (A) Primary human monocytes were incubated in the presence of Signal 1: LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 h, IL‐27 (100 ng/ml) for 16 h, or IL‐27 for 16 h plus LPS for the final 4 h. (B) CD14–THP‐1 cells were incubated in the presence of LPS (100 ng/ml), IL‐27 (100 ng/ml), or LPS plus IL‐27 for 16 h. Cells were then stained for P2X7 and CD14. All data sets were measured using flow cytometry and analyzed using FlowJo software, version 10.0.7r2. Cells were gated for live cells and then CD14+ monocytic cells. Lines indicate stained cells, and filled histograms represent isotype controls. Histograms are representative of six replicate experiments. Fold increase was calculated relative to medium per individual experiment and plotted for each experiment as the average fold increase. Error bars indicate se of all replicates. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01, Wilcoxon signed‐rank test used for analysis relative to medium, given a hypothetical value of 1.0 and unpaired, 2‐tailed t test used for analysis between other groups.

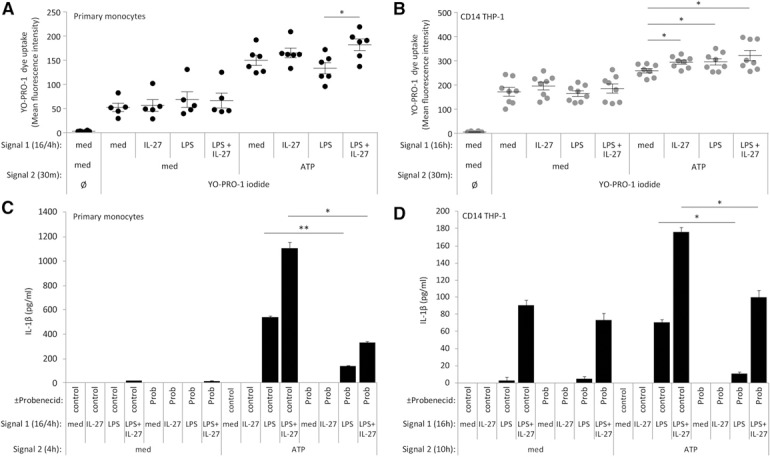

To investigate whether IL‐27 treatment leads to increased P2X7 receptor function, we used the YO‐PRO‐1 iodide dye uptake assay [44]. YO‐PRO‐1 iodide is a nucleic acid stain that enters cells through ATP‐gated pannexin‐1 channels, whereby increased dye uptake correlates with greater ATP/P2X7 function and pore formation. CD14–THP‐1 cells were stimulated for 16 h with LPS plus IL‐27, whereas primary human monocytes were treated for 16 h with IL‐27 plus LPS in the last 4 h. Cells were treated with YO‐PRO‐1 iodide for 15 min before measurement of dye uptake. In both cell types, basal levels of dye uptake were observed upon treatment with IL‐27 alone, LPS alone, or IL‐27 plus LPS ( Fig. 8A and B ). In response to ATP addition, in primary human monocytes, there was significantly increased YO‐PRO‐1 uptake in LPS plus IL‐27‐stimulated cells compared with LPS‐treated cells (Fig. 8A). In CD14–THP‐1 cells, ATP stimulation resulted in significantly greater YO‐PRO‐1 dye uptake in LPS alone, IL‐27 alone, and LPS plus IL‐27 pretreatment compared with medium controls (Fig. 8B). These data support a potential mechanism for IL‐27 to modulate inflammasome activation via enhancement of the P2X7 receptor function.

Figure 8.

IL‐27 up‐regulates P2X7 receptor function for enhanced LPS‐induced IL‐1β production. (A) Primary human monocytes were incubated in the presence of Signal 1: LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 h, IL‐27 (100 ng/ml) for 16 h, or IL‐27 for 16 h plus LPS for the final 4 h. Cells were washed and given fresh media and then incubated with YO‐PRO‐1 iodide (1 μM) and Signal 2: ATP (5 mM) for 15 min at 37°C. (B) CD14–THP‐1 cells were incubated in the presence of LPS (100 ng/ml), IL‐27 (100 ng/ml), or LPS plus IL‐27 for 16 h. Cells were washed and given fresh media and then incubated with YO‐PRO‐1 iodide (1 μM) and ATP (5 mM) for 15 min at 37°C. Data were measured using flow cytometry and analyzed using FlowJo software, version 10.0.7r2. Each dot indicates an independent experiment. (C) Primary human monocytes were incubated in the presence of probenecid (Prob; 1 μM) for 16 h, along with Signal 1: LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 h, IL‐27 (100 ng/ml) for 16 h, or IL‐27 for 16 h plus LPS for the final 4 h. Cells were washed and resuspended in new media and then exposed to probenecid (1 μM) for 4 h, along with Signal 2: ATP (5 mM) for 4 h. Secreted levels of IL‐1β were measured by ELISA in cell‐free supernatants. (D) CD14–THP‐1 cells were incubated in the presence of probenecid (1 μM) for 16 h along with Signal 1: LPS (100 ng/ml), IL‐27 (100 ng/ml), or LPS plus IL‐27 for 16 h. Cells were washed and resuspended in new media and then exposed to probenecid (1 μM) for 10 h, along with Signal 2: ATP (5 mM) and for 10 h. Secreted levels of IL‐1β were measured by ELISA in cell‐free supernatants. Data sets are representative of at least six replicate experiments. Error bars indicate (A and B) sem of all replicates or (C and D) sd of technical replicates. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01, unpaired, 2‐tailed t test.

As ATP binding of the P2X7 receptor results in opening pannexin‐1 hemichannels for ion exchange [32], we investigated the requirement of pannexin‐1 in our model. Pannexin‐1 pore function was inhibited using probenecid, which blocks the organic anion currents, thus abrogating P2X7 signaling [45]. Therefore, to elucidate the role of the pannexin‐1/P2X7 axis in our model, we added probenecid (1 mM) concomitantly with both Signals 1 and 2. In both cell types, probenecid abrogated ATP‐induced IL‐1β production (Fig. 8C and D). Taken together, these data establish an essential role for pannexin‐1 channel function in optimal IL‐27‐mediated, LPS‐induced IL‐1β production.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that simultaneous addition of IL‐27 with LPS in vitro augments IL‐1β production from human monocytes. We determined that this response was dependent on NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase‐1 activation and that induction of TLR4 expression may account for enhanced LPS‐induced IL‐1β production. Moreover, IL‐27‐mediated effects on the P2X7 receptor and pannexin‐1 activation are integral to the enhanced IL‐1β production in our model system.

As IL‐27 is produced in response to LPS stimulation [46, 47], we reasoned that IL‐27 may act in an autocrine manner to promote LPS‐mediated inflammasome formation. Indeed, in WSX‐1‐deficient (IL‐27Ra−/−) BMDMs, we observed significantly lower levels of LPS/ATP‐induced IL‐1β secretion compared with WT BMDM. In contrast to our observations, Mascanfroni et al. [48] demonstrated that murine conventional dendritic cells, costimulated with IL‐27 and LPS for 48 h, exhibited decreased inflammasome activation and IL‐1β production. However, it should be noted that IL‐27 function, in the context of LPS responsiveness, may depend on cell type and activation status. In particular, different APCs, such as macrophages or dendritic cells, respond differently to LPS stimulation in the absence of IL‐27 signaling. In support of our data, others have shown that peritoneal macrophages from WSX‐1‐deficient mice exhibit decreased levels of cytokines in response to LPS/IFN‐γ stimulation [7]. However, dendritic cells isolated from WSX‐1‐deficient mice displayed enhanced TNF‐α and IL‐12p40 production in response to LPS stimulation [49]. In our study, decreased IL‐1β secretion in IL‐27Ra−/− BMDMs suggests that IL‐27 plays a pertinent role in production of this cytokine.

To identify the mechanisms affected by exogenous IL‐27 treatment of human monocytes responsible for enhanced IL‐1β secretion, we examined several key steps required for inflammasome activation. Our data demonstrate a requirement for caspase‐1 activation in IL‐1β production in both primary monocytes and THP‐1 cells. Although procaspase‐1 expression was induced by IL‐27, no corresponding significant changes in caspase‐1 activity levels were observed. Moreover, we show that LPS plus IL‐27 (Signal 1), followed by ATP (Signal 2), resulted in greater caspase‐1 activity compared with LPS/ATP alone, even though protein levels of procaspase‐1 remained unchanged. In primary human monocytes, the difference in caspase‐1 activity levels did not reach statistical significance; however, the data follow the same trend observed in THP‐1 cells. This greater caspase‐1 activity represents a possible mechanism driving enhanced IL‐1β production.

As IL‐27 enhances LPS‐induced NF‐κB activation in human monocytes [13], and NF‐κB induces pro‐IL‐1β and NLRP3 expression [20, 50], it is possible that dual stimulation with LPS and IL‐27 up‐regulates expression of these proteins. Although we show that IL‐27 alone did not impact pro‐IL‐1β protein expression in our model, others demonstrated that IL‐27 treatment of human primary monocytes resulted in enhanced levels of IL‐1β mRNA [6]. We observed that costimulation of IL‐27 and LPS resulted in a modest increase in pro‐IL‐1β expression compared with LPS alone in CD14–THP‐1 cells; however, this up‐regulation was not observed in primary monocytes. This indicates that at least for primary monocytes, other IL‐27‐mediated mechanisms could modulate the capacity of the cells to produce IL‐1β in response to LPS/ATP.

Previously established in our lab, IL‐27 enhances TLR4 surface expression and LPS responsiveness in human monocytes [13]. As LPS signaling also requires CD14 and the scaffold protein MD2 [51, 52–53], we examined whether IL‐27, with or without LPS, could also modulate surface expression of these proteins. In both cell types, treatment with IL‐27 alone or in conjunction with LPS resulted in significantly enhanced TLR4 expression compared with LPS treatment alone. Likewise, in CD14–THP‐1 cells, LPS plus IL‐27 moderately up‐regulated MD2 surface expression compared with LPS alone. However, in primary human monocytes, no differences in MD2 levels were observed. In primary monocytes, dual stimulation with LPS and IL‐27 resulted in lower TLR4 expression compared with IL‐27 alone, whereas in CD14–THP‐1 cells, TLR4 expression remained consistent between these 2 conditions. When LPS is complexed with CD14–TLR4–MD2, it initiates MyD88 signaling, and the complex is subsequently endocytosed to signal through the Toll/IL‐1R domain‐containing adapter inducing IFN‐β pathway [54, 55]. Thus, internalization of the LPS–TLR4 complex in primary monocytes may result in lower amounts of TLR4 present on the cell surface. It should also be noted that the CD14–THP‐1 cells constitutively express CD14; therefore, it is possible that TLR4 expression is more stable at the cell surface, as it may be refractory to internalization.

ATP as Signal 2 has been well characterized to induce NLRP3‐mediated IL‐1β secretion from LPS‐treated cells [27, 56]. Indeed, our data demonstrate that NLRP3 induction is required for IL‐1β production. However, IL‐27 did not impact NLRP3 protein levels. Moreover, IL‐27/LPS pretreatment was unable to enhance IL‐1β production over that of LPS pretreatment alone, in response to stimulation with nigericin, another NLRP3–inflammasome activator. In contrast to ATP, nigericin is a pore‐forming toxin, which triggers NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the absence of P2X7 receptor expression [57]. Therefore, we examined the effect of IL‐27 on P2X7 receptor levels. Cells costimulated with LPS and IL‐27 demonstrated enhanced P2X7 receptor expression that correlated with the trend of enhanced YO‐PRO dye uptake compared with LPS treatment alone. Interestingly, other cytokines have been shown to play a role in P2X7 function; TNF‐α increases P2X7 expression, as well as calcium ion uptake [58]. As we demonstrated previously that IL‐27 enhances TNF‐α expression in human monocytes [8], it is possible that IL‐27‐induced intermediates, such as TNF‐α, could play a role in enhancing P2X7 receptor expression and function. In primary monocytes, levels of P2X7 expression in cells treated with IL‐27/LPS were slightly lower than IL‐27 alone; this could be a result of endogenous LPS‐induced ATP production causing P2X7 receptor internalization [59]. Further examination of P2X7 receptor levels and rates of internalization are needed to delineate the specific requirement for P2X7 in IL‐27‐mediated IL‐1β production. Moreover, examination of endogenous ATP and P2X7 receptor levels in IL‐27ra−/− animals is needed to provide further insight into the role of IL‐27 and P2X7 receptor activation.

Upon ATP/P2X7 ligation, the hemichannel pannexin‐1 forms a pore, facilitating potassium efflux required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation detectable by YO‐PRO‐1 dye uptake [30, 32]. LPS plus IL‐27 enhanced ATP‐mediated YO‐PRO‐1 dye uptake, indicating that the pannexin‐1 hemichannel function is a potential factor integral to IL‐27‐enhanced IL‐1β production. Although expression levels of pannexin‐1 were unchanged by LPS or IL‐27 stimulation, treatment with the pannexin‐1 inhibitor, probenecid, showed a requirement for activation of the pannexin‐1 channel to elicit IL‐1β secretion in our model. Taken together, our data suggest that IL‐27‐mediated effects on inflammasome formation require activation of the pannexin‐1/P2X7 axis.

Herein, we demonstrate a role for IL‐27 in promoting inflammasome activation in response to LPS triggering, indicating that during bacterial infection, IL‐27 may function to prime monocytes and macrophages to respond with an optimal inflammatory response. Thus, this work provides support for further research into the role of this cytokine in the regulation of myeloid cell responses during infection and inflammation.

AUTHORSHIP

C.P. and C.W. conceived of the study, designed and performed experiments, and analyzed data. C.P. and K.G. wrote the manuscript. C.G., D.M., and S.L. performed experiments and analyzed data. B.W.B. and S.B. provided advice, reagents, and intellectual input. A.C. provided knockout mice. K.G. conceived of the study, designed and performed experiments, and supervised all aspects of the study.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and Queen's University Senate Advisory Research Council (SARC). C.P. was supported by Ontario Graduate Scholarship, Dr. Robert John Wilson Graduate Fellowship, and NSERC‐Postgraduate Scholarships–Doctoral (PGS D). C.W. was supported by an NSERC Alexander Graham Bell studentship. C.G. was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Vanier Award and a studentship from the Ontario HIV Treatment Network.

REFERENCES

- 1. Batten, M. , Ghilardi, N. (2007) The biology and therapeutic potential of interleukin 27. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 85, 661–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kastelein, R. A. , Hunter, C. A. , Cua, D. J. (2007) Discovery and biology of IL‐23 and IL‐27: related but functionally distinct regulators of inflammation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 221–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Villarino, A. V. , Huang, E. , Hunter, C. A. (2004) Understanding the pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory properties of IL‐27. J. Immunol. 173, 715–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pflanz, S. , Timans, J. C. , Cheung, J. , Rosales, R. , Kanzler, H. , Gilbert, J. , Hibbert, L. , Churakova, T. , Travis, M. , Vaisberg, E. , Blumenschein, W. M. , Mattson, J. D. , Wagner, J. L. , To, W. , Zurawski, S. , McClanahan, T. K. , Gorman, D. M. , Bazan, J. F. , de Waal Malefyt, R. , Rennick, D. , Kastelein, R. A. (2002) IL‐27, a heterodimeric cytokine composed of EBI3 and p28 protein, induces proliferation of naive CD4+ T cells. Immunity 16, 779–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gee, K. , Guzzo, C. , Che Mat, N. F. , Ma, W. , Kumar, A. (2009) The IL‐12 family of cytokines in infection, inflammation and autoimmune disorders. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets 8, 40–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pflanz, S. , Hibbert, L. , Mattson, J. , Rosales, R. , Vaisberg, E. , Bazan, J. F. , Phillips, J. H. , McClanahan, T. K. , de Waal Malefyt, R. , Kastelein, R. A. (2004) WSX‐1 and glycoprotein 130 constitute a signal‐transducing receptor for IL‐27. J. Immunol. 172, 2225–2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hölscher, C. , Hölscher, A. , Rückerl, D. , Yoshimoto, T. , Yoshida, H. , Mak, T. , Saris, C. , Ehlers, S. (2005) The IL‐27 receptor chain WSX‐1 differentially regulates antibacterial immunity and survival during experimental tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 174, 3534–3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guzzo, C. , Che Mat, N. F. , Gee, K. (2010) Interleukin‐27 induces a STAT1/3‐ and NF‐kappaB‐dependent proinflammatory cytokine profile in human monocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24404–24411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brender, C. , Tannahill, G. M. , Jenkins, B. J. , Fletcher, J. , Columbus, R. , Saris, C. J. , Ernst, M. , Nicola, N. A. , Hilton, D. J. , Alexander, W. S. , Starr, R. (2007) Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 regulates CD8 T‐cell proliferation by inhibition of interleukins 6 and 27. Blood 110, 2528–2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Owaki, T. , Asakawa, M. , Kamiya, S. , Takeda, K. , Fukai, F. , Mizuguchi, J. , Yoshimoto, T. (2006) IL‐27 suppresses CD28‐mediated [correction of medicated] IL‐2 production through suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. J. Immunol. 176, 2773–2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yoshimura, T. , Takeda, A. , Hamano, S. , Miyazaki, Y. , Kinjyo, I. , Ishibashi, T. , Yoshimura, A. , Yoshida, H. (2006) Two‐sided roles of IL‐27: induction of Th1 differentiation on naive CD4+ T cells versus suppression of proinflammatory cytokine production including IL‐23‐induced IL‐17 on activated CD4+ T cells partially through STAT3‐dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 177, 5377–5385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Owaki, T. , Asakawa, M. , Morishima, N. , Hata, K. , Fukai, F. , Matsui, M. , Mizuguchi, J. , Yoshimoto, T. (2005) A role for IL‐27 in early regulation of Th1 differentiation. J. Immunol. 175, 2191–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guzzo, C. , Ayer, A. , Basta, S. , Banfield, B. W. , Gee, K. (2012) IL‐27 enhances LPS‐induced proinflammatory cytokine production via upregulation of TLR4 expression and signaling in human monocytes. J. Immunol. 188, 864–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kalliolias, G. D. , Ivashkiv, L. B. (2008) IL‐27 activates human monocytes via STAT1 and suppresses IL‐10 production but the inflammatory functions of IL‐27 are abrogated by TLRs and p38. J. Immunol. 180, 6325–6333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shimizu, M. , Ogura, K. , Mizoguchi, I. , Chiba, Y. , Higuchi, K. , Ohtsuka, H. , Mizuguchi, J. , Yoshimoto, T. (2013) IL‐27 promotes nitric oxide production induced by LPS through STAT1, NF‐kB and MAPKs. Immunobiology 218, 628–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schnurr, M. , Toy, T. , Shin, A. , Wagner, M. , Cebon, J. , Maraskovsky, E. (2005) Extracellular nucleotide signaling by P2 receptors inhibits IL‐12 and enhances IL‐23 expression in human dendritic cells: a novel role for the cAMP pathway. Blood 105, 1582–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smits, H. H. , van Beelen, A. J. , Hessle, C. , Westland, R. , de Jong, E. , Soeteman, E. , Wold, A. , Wierenga, E. A. , Kapsenberg, M. L. (2004) Commensal gram‐negative bacteria prime human dendritic cells for enhanced IL‐23 and IL‐27 expression and enhanced Th1 development. Eur. J. Immunol. 34, 1371–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schroder, K. , Tschopp, J. (2010) The inflammasomes. Cell 140, 821–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martinon, F. , Burns, K. , Tschopp, J. (2002) The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL‐beta. Mol. Cell 10, 417–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bauernfeind, F. G. , Horvath, G. , Stutz, A. , Alnemri, E. S. , MacDonald, K. , Speert, D. , Fernandes‐Alnemri, T. , Wu, J. , Monks, B. G. , Fitzgerald, K. A. , Hornung, V. , Latz, E. (2009) Cutting edge: NF‐kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J. Immunol. 183, 787–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mitroulis, I. , Skendros, P. , Ritis, K. (2010) Targeting IL‐1beta in disease; the expanding role of NLRP3 inflammasome. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 21, 157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koizumi, Y. , Toma, C. , Higa, N. , Nohara, T. , Nakasone, N. , Suzuki, T. (2012) Inflammasome activation via intracellular NLRs triggered by bacterial infection. Cell. Microbiol. 14, 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Carneiro, L. A. , Magalhaes, J. G. , Tattoli, I. , Philpott, D. J. , Travassos, L. H. (2008) Nod‐like proteins in inflammation and disease. J. Pathol. 214, 136–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fritz, J. H. , Ferrero, R. L. , Philpott, D. J. , Girardin, S. E. (2006) Nod‐like proteins in immunity, inflammation and disease. Nat. Immunol. 7, 1250–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kanneganti, T. D. , Ozören, N. , Body‐Malapel, M. , Amer, A. , Park, J. H. , Franchi, L. , Whitfield, J. , Barchet, W. , Colonna, M. , Vandenabeele, P. , Bertin, J. , Coyle, A. , Grant, E. P. , Akira, S. , Núñez, G. (2006) Bacterial RNA and small antiviral compounds activate caspase‐1 through cryopyrin/Nalp3. Nature 440, 233–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kahlenberg, J. M. , Lundberg, K. C. , Kertesy, S. B. , Qu, Y. , Dubyak, G. R. (2005) Potentiation of caspase‐1 activation by the P2X7 receptor is dependent on TLR signals and requires NF‐kappaB‐driven protein synthesis. J. Immunol. 175, 7611–7622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Perregaux, D. G. , McNiff, P. , Laliberte, R. , Conklyn, M. , Gabel, C. A. (2000) ATP acts as an agonist to promote stimulus‐induced secretion of IL‐1 beta and IL‐18 in human blood. J. Immunol. 165, 4615–4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cruz, C. M. , Rinna, A. , Forman, H. J. , Ventura, A. L. , Persechini, P. M. , Ojcius, D. M. (2007) ATP activates a reactive oxygen species‐dependent oxidative stress response and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 2871–2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pétrilli, V. , Papin, S. , Dostert, C. , Mayor, A. , Martinon, F. , Tschopp, J. (2007) Activation of the NALP3 inflammasome is triggered by low intracellular potassium concentration. Cell Death Differ. 14, 1583–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Franchi, L. , Kanneganti, T. D. , Dubyak, G. R. , Núñez, G. (2007) Differential requirement of P2X7 receptor and intracellular K+ for caspase‐1 activation induced by intracellular and extracellular bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 18810–18818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Muñoz‐Planillo, R. , Kuffa, P. , Martínez‐Colón, G. , Smith, B. L. , Rajendiran, T. M. , Núñez, G. (2013) K+ efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity 38, 1142–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pelegrin, P. , Surprenant, A. (2006) Pannexin‐1 mediates large pore formation and interleukin‐1beta release by the ATP‐gated P2X7 receptor. EMBO J. 25, 5071–5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Colomar, A. , Marty, V. , Médina, C. , Combe, C. , Parnet, P. , Amédée, T. (2003) Maturation and release of interleukin‐1beta by lipopolysaccharide‐primed mouse Schwann cells require the stimulation of P2X7 receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 30732–30740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kahlenberg, J. M. , Dubyak, G. R. (2004) Mechanisms of caspase‐1 activation by P2X7 receptor‐mediated K+ release. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286, C1100–C1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alatery, A. , Basta, S. (2008) An efficient culture method for generating large quantities of mature mouse splenic macrophages. J. Immunol. Methods 338, 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pearl, J. E. , Khader, S. A. , Solache, A. , Gilmartin, L. , Ghilardi, N. , de Sauvage, F. , Cooper, A. M. (2004) IL‐27 signaling compromises control of bacterial growth in mycobacteria‐infected mice. J. Immunol. 173, 7490–7496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen, Q. , Ghilardi, N. , Wang, H. , Baker, T. , Xie, M. H. , Gurney, A. , Grewal, I. S. , de Sauvage, F. J. (2000) Development of Th1‐type immune responses requires the type I cytokine receptor TCCR. Nature 407, 916–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Perregaux, D. , Gabel, C. A. (1994) Interleukin‐1 beta maturation and release in response to ATP and nigericin. Evidence that potassium depletion mediated by these agents is a necessary and common feature of their activity. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 15195–15203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gicquel, T. , Robert, S. , Loyer, P. , Victoni, T. , Bodin, A. , Ribault, C. , Gleonnec, F. , Couillin, I. , Boichot, E. , Lagente, V. (2015) IL‐1β production is dependent on the activation of purinergic receptors and NLRP3 pathway in human macrophages. FASEB J. 29, 4162–4173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lamkanfi, M. , Mueller, J. L. , Vitari, A. C. , Misaghi, S. , Fedorova, A. , Deshayes, K. , Lee, W. P. , Hoffman, H. M. , Dixit, V. M. (2009) Glyburide inhibits the cryopyrin/Nalp3 inflammasome. J. Cell Biol. 187, 61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Coll, R. C. , Robertson, A. , Butler, M. , Cooper, M. , O'Neill, L. A. (2011) The cytokine release inhibitory drug CRID3 targets ASC oligomerisation in the NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasomes. PLoS One 6, e29539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mariathasan, S. , Weiss, D. S. , Newton, K. , McBride, J. , O'Rourke, K. , Roose‐Girma, M. , Lee, W. P. , Weinrauch, Y. , Monack, D. M. , Dixit, V. M. (2006) Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature 440, 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Katsnelson, M. A. , Rucker, L. G. , Russo, H. M. , Dubyak, G. R. (2015) K+ efflux agonists induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation independently of Ca2+ signaling. J. Immunol. 194, 3937–3952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gadeock, S. , Pupovac, A. , Sluyter, V. , Spildrejorde, M. , Sluyter, R. (2012) P2X7 receptor activation mediates organic cation uptake into human myeloid leukaemic KG‐1 cells. Purinergic Signal. 8, 669–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Silverman, W. , Locovei, S. , Dahl, G. (2008) Probenecid, a gout remedy, inhibits pannexin 1 channels. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 295, C761–C767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhu, C. L. , Cao, Y. H. , Zhang, R. , Song, Y. , Liu, W. Y. , Pan, F. , Li, Y. , Zhu, Y. , Liu, F. , Wu, J. G. (2010) Stimulatory effect of LPS and feedback effect of PGE2 on IL‐27 production. Scand. J. Immunol. 72, 469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu, J. , Guan, X. , Ma, X. (2007) Regulation of IL‐27 p28 gene expression in macrophages through MyD88‐ and interferon‐gamma‐mediated pathways. J. Exp. Med. 204, 141–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mascanfroni, I. D. , Yeste, A. , Vieira, S. M. , Burns, E. J. , Patel, B. , Sloma, I. , Wu, Y. , Mayo, L. , Ben‐Hamo, R. , Efroni, S. , Kuchroo, V. K. , Robson, S. C. , Quintana, F. J. (2013) IL‐27 acts on DCs to suppress the T cell response and autoimmunity by inducing expression of the immunoregulatory molecule CD39. Nat. Immunol. 14, 1054–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang, S. , Miyazaki, Y. , Shinozaki, Y. , Yoshida, H. (2007) Augmentation of antigen‐presenting and Th1‐promoting functions of dendritic cells by WSX‐1(IL‐27R) deficiency. J. Immunol. 179, 6421–6428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cogswell, J. P. , Godlevski, M. M. , Wisely, G. B. , Clay, W. C. , Leesnitzer, L. M. , Ways, J. P. , Gray, J. G. (1994) NF‐kappa B regulates IL‐1 beta transcription through a consensus NF‐kappa B binding site and a nonconsensus CRE‐like site. J. Immunol. 153, 712–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wright, S. D. , Ramos, R. A. , Tobias, P. S. , Ulevitch, R. J. , Mathison, J. C. (1990) CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science 249, 1431–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pugin, J. , Schürer‐Maly, C. C. , Leturcq, D. , Moriarty, A. , Ulevitch, R. J. , Tobias, P. S. (1993) Lipopolysaccharide activation of human endothelial and epithelial cells is mediated by lipopolysaccharide‐binding protein and soluble CD14. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 2744–2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Doyle, S. L. , O'Neill, L. A. (2006) Toll‐like receptors: from the discovery of NFkappaB to new insights into transcriptional regulations in innate immunity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 72, 1102–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim, D. , Kim, J. Y. (2014) Anti‐CD14 antibody reduces LPS responsiveness via TLR4 internalization in human monocytes. Mol. Immunol. 57, 210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Husebye, H. , Halaas, Ø. , Stenmark, H. , Tunheim, G. , Sandanger, Ø. , Bogen, B. , Brech, A. , Latz, E. , Espevik, T. (2006) Endocytic pathways regulate Toll‐like receptor 4 signaling and link innate and adaptive immunity. EMBO J. 25, 683–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Grahames, C. B. , Michel, A. D. , Chessell, I. P. , Humphrey, P. P. (1999) Pharmacological characterization of ATP‐ and LPS‐induced IL‐1beta release in human monocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 127, 1915–1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Qu, Y. , Misaghi, S. , Newton, K. , Gilmour, L. L. , Louie, S. , Cupp, J. E. , Dubyak, G. R. , Hackos, D. , Dixit, V. M. (2011) Pannexin‐1 is required for ATP release during apoptosis but not for inflammasome activation. J. Immunol. 186, 6553–6561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Castrichini, M. , Lazzerini, P. E. , Gamberucci, A. , Capecchi, P. L. , Franceschini, R. , Natale, M. , Hammoud, M. , Moramarco, A. , Zimbone, S. , Gianchecchi, E. , Montilli, C. , Ricci, G. , Selvi, E. , Cantarini, L. , Galeazzi, M. , Laghi‐Pasini, F. (2014) The purinergic P2×7 receptor is expressed on monocytes in Behçet's disease and is modulated by TNF‐α. Eur. J. Immunol. 44, 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Feng, Y. H. , Wang, L. , Wang, Q. , Li, X. , Zeng, R. , Gorodeski, G. I. (2005) ATP stimulates GRK‐3 phosphorylation and beta‐arrestin‐2‐dependent internalization of P2X7 receptor. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 288, C1342–C1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]