Short abstract

Review of EBOV pathogenesis, current vaccine and therapeutic candidates, and mechanisms of viral persistence and long‐term health sequelae for EBOV disease survivors.

Keywords: viral hemorrhagic fever, immunoevasion, antivirals, Ebola vaccines, Ebola survivors

Abstract

Ebola viruses (EBOVs) and Marburg viruses (MARVs) are among the deadliest human viruses, as highlighted by the recent and widespread Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa, which was the largest and longest epidemic of Ebola virus disease (EVD) in history, resulting in significant loss of life and disruptions across multiple continents. Although the number of cases has nearly reached its nadir, a recent cluster of 5 cases in Guinea on March 17, 2016, has extended the enhanced surveillance period to June 15, 2016. New, enhanced 90‐d surveillance windows replaced the 42‐d surveillance window to ensure the rapid detection of new cases that may arise from a missed transmission chain, reintroduction from an animal reservoir, or more important, reemergence of the virus that has persisted in an EVD survivor. In this review, we summarize our current understanding of EBOV pathogenesis, describe vaccine and therapeutic candidates in clinical trials, and discuss mechanisms of viral persistence and long‐term health sequelae for EVD survivors.

Abbreviations

- ALT

= alanine aminotransferase

- BCL2

= B cell lymphoma 2

- BEBOV

= Bundibugyo Ebola virus

- CFR

= case fatality rate

- CHO

= Chinese hamster ovary

- CIEBOV

= Ivory Coast Ebola virus

- Ct

= cycle threshold

- DC

= dendritic cell

- EBOV

= Ebola virus

- EVD

= Ebola virus disease

- FDA

= U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- GP

= glycoprotein

- HSPA5

= heat shock 70 kDa protein 5

- hu

= humanized

- IFNAR

= interferon α/β receptor

- IKKɛ

= I‐κ‐B kinase ɛ

- IRF

= interferon regulatory factor

- KIR

= killer Ig‐like receptor

- KPN‐α1

= karyopherin α‐1

- L

= Ebola RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase

- MA

= mouse adapted

- MARV

= Marburg virus

- NHP

= nonhuman primate

- NIAID

= U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

- NP

= nucleoprotein

- NPC1

= Niemann‐Pick C1

- PACT

= PKR‐activating protein

- PIAS1

= protein inhibitor of activated STAT‐1

- PKR

= protein kinase R

- PMO

= phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer

- qRT‐PCR

= quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction

- rAd

= recombinant adenovirus

- rChAd3

= recombinant chimpanzee adenovirus 3

- RLR

= RIG‐I like receptor

- RPL/RPS

= ribosomal protein

- rVSV

= recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus

- SEBOV

= Sudan Ebola virus

- sGP

= secreted glycoprotein

- SNALP

= stable nucleic acid‐lipid particles

- SUMO

= small ubiquitin‐like modifier

- TBK1

= TANK binding kinase‐1

- TF

= tissue factor

- TRAIL

= TNF related apoptosis inducing ligand

- UBC

= ubiquitin C

- Ubc9

= ubiquitin conjugating enzyme

- VP

= viral protein

- WHO

= World Health Organization

- WT

= wild‐type

- ZEBOV

= Zaire Ebola virus

Introduction

The filoviruses EBOV and MARV are among the deadliest reemerging viruses. Infection in humans results in hemorrhagic fever with CFRs of 90% in some outbreaks. The first identified instance of filovirus hemorrhagic fever occurred in 1967 in Marburg, Germany, when animal staff and laboratory workers became infected while processing tissues from Cercopithecus aethiops monkeys, which were imported from Uganda to produce kidney cell cultures needed for the production of a live poliomyelitis vaccine [1, 2]. Electron microscopy identified the causative agent as Marburg virus [3]. In the following years, small, sporadic outbreaks of MARV occurred in Africa, with the largest occurring in 2004 in Angola, with 252 cases and CFRs of 90% [4, 5].

Hemorrhagic fever caused by a second filovirus, Ebola, was first reported in 1976 when simultaneous outbreaks occurred in northern Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Sudan, with 318 cases (CFRs of 88%) and 284 cases (CFRs of 53%), respectively [6]. These 2 epidemics were caused by 2 species of Ebola virus, ZEBOV and SEBOV. Subsequent outbreaks of EBOV revealed the presence of 3 additional species with varying pathogenicity in humans. In 1989, the Reston Ebola virus was discovered in the United States during an outbreak of viral hemorrhagic fever among cynomolgus macaques imported from the Philippines and was found to be nonpathogenic in humans [7]. In 1994, CIEBOV was isolated from an ethologist who was infected while conducting a necropsy on a chimpanzee in the Tai Forest reserve in Cote d'Ivoire; it was nonfatal and remains the only documented case [8]. Finally, BEBOV was discovered in 2007 in Uganda, where it caused an outbreak of 149 cases with a 25% lethality rate. ZEBOV is responsible for the most Ebola outbreaks, with multiple strains identified. By the end of 2013, there had been 1383 ZEBOV cases, 779 SEBOV cases, and 185 BEBOV cases occurring in remote regions of central Africa [9].

In December 2013, ZEBOV emerged in Guinea, then quickly spread to Sierra Leone and Liberia, leading to the largest EBOV epidemic in history. The new ZEBOV strain responsible for this epidemic was named Makona after the river that borders these 3 countries. Concurrently, in August 2014, the WHO was notified of an unrelated ZEBOV outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which resulted in 66 cases and a 74% lethality rate. As of March 2016, 28,646 confirmed, probable, and suspected cases of ZEBOV disease and 11,323 deaths have been reported across 10 countries (Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, United States, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Spain, United Kingdom, and Italy). Although sporadic cases of Ebola virus continue to occur in Sierra Leone (January 14, 2016) and Guinea (March 17, 2016), the WHO declared the end of the Public Health Emergency of International Concern regarding the Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa on March 29, 2016. A study that compared the virulence of Makona with that of Mayinga (responsible for the 1976 outbreak), in cynomolgus macaques, showed that, although infection with both strains was uniformly lethal, disease progression was delayed in Makona‐infected animals [10]. The mechanisms underlying the differences in disease severity and fatality rates among species and strains are not fully understood.

Filovirus infections are acquired by direct contact with infected bodily fluids and enter the human body via breaks in the skin or through mucosal surfaces [11]. The incubation period ranges from 2 to 21 d with an average of 5–7 d. Early symptoms are nonspecific, including fever, chills, malaise, and myalgia. Subsequent symptoms that signal multisystem involvement are gastrointestinal (anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea), respiratory (chest pain, shortness of breath, cough, nasal discharge), and vascular (postural hypotension, edema). During the terminal stage of the disease, there is an increase in vascular permeability, massive tissue injury, dysregulation of the coagulation cascade, and hemorrhage. Hemorrhagic manifestations include petechiae, ecchymoses, and mucosal hemorrhages. Multiorgan failure and shock are usually the main causes of death [8, 12, 13]. Laboratory diagnosis of filovirus infections can be achieved by measuring EBOV‐specific IgG and IgM Abs (ELISA), viral nucleic acid (RT‐PCR), or viral antigens (ELISA) [14].

The high virulence of EBOV is attributed in large part to the ability of this virus to interfere with the host immune response. Currently, there are no approved vaccines or postexposure therapeutics for patients infected with EBOV. However, in light of the recent outbreak, several vaccine platforms and therapeutics have been accelerated for clinical trials. With >17,000 survivors and new reports of post‐EBOV symptoms and viral persistence during convalescence, the risk of reemergence of EBOV remains high. In this review, we discuss our current understanding of EBOV pathogenesis and its ability to subvert host immunity, the vaccine platforms and postexposure therapeutics currently being evaluated, and summarize studies assessing the long‐term health consequences of EBOV infection.

EBOV STRUCTURE AND LIFE CYCLE

Ebola virus is a filamentous, enveloped virus containing a 19‐kb, negative‐strand RNA genome that encodes 7 genes and 9 proteins [15]. At the genome ends, short, extragenic regions, called leader and trailer sequences, contain encapsidation signals as well as replication and transcription promoters. The leader region contains signals for initiation of RNA synthesis by the viral, RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase, in addition to signals that direct packaging of full‐length, negative strand copies of the viral genome in nucleocapsids. The trailer region, located at the 3′ end of the antigenome RNA, contains the promoter for genome replication [16, 17–18].

The 9 proteins encoded by EBOV genome include GP, RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase (L), NP, and 4 VPs: 24, 30, 35, and 40. The GP is the only surface protein on the viral envelope and is important in mediating receptor binding and fusion [19, 20–21]. EBOV also encodes soluble forms of GP—sGP, and small sGP—through RNA editing [22, 23–24]. VP40 is a matrix protein located beneath the viral membrane, where it maintains structural integrity of viral particles [20, 25]. Expression of VP40 alone in mammalian cells can also induce its own release and formation of virus‐like particles in the absence of other VPs and, thus, is important in filovirus budding [26]. VP24 is a secondary matrix protein that contributes to nucleocapsid formation. NP, VP35, VP30, and L are associated with the viral RNA genome, forming the nucleocapsid [17, 27]. NP is the structural component of the nucleocapsid complex but can also catalyze replication and transcription of the RNA genome. The active polymerase complex is composed of VP35 (a polymerase cofactor) and L (polymerase) [17, 18]. VP30 is a transcriptional activator and a major component of the RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase. VP24 and VP35 also contribute to innate immune evasion by antagonizing type I IFN responses (discussed in a later section).

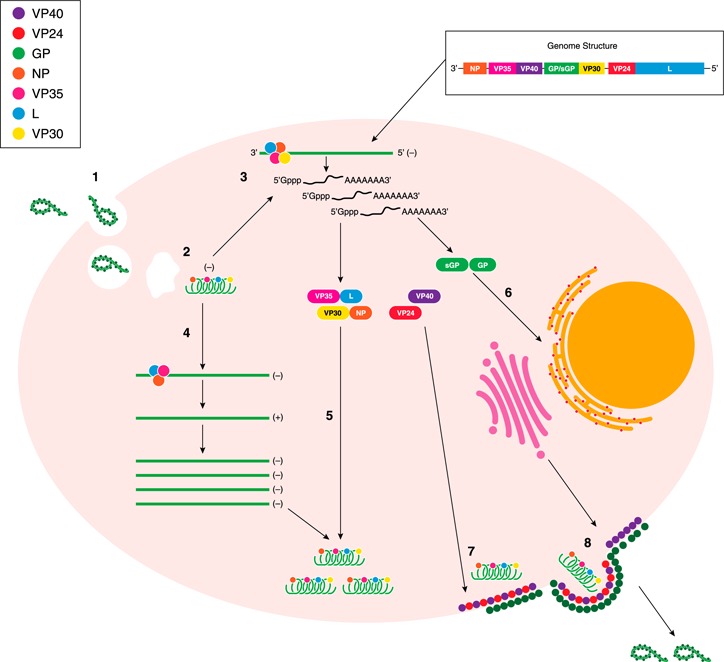

Host receptors used by the virus to gain entry include the asialoglycoprotein receptor on hepatocytes; the folate receptor α on epithelial cells; C‐type lectins, such as DC‐specific intercellular adhesion molecule‐3‐grabbing nonintegrin and its receptor (on DCs, macrophages, and endothelial cells); and human macrophage lectin specific for galactose/N‐acetylgalactosamine (on macrophages) [14, 28]. Once GP binds its receptor, virions enter the cell by process of endocytosis. The acidification of endocytic vesicles is followed by a fusion of virus and host membranes and the release of EBOV into the cytoplasm [29, 30, 31–32] ( Fig. 1 ). Endosomal protein NPC1 is an additional entry receptor that has recently been shown to bind EBOV GP through domain C, resulting in a conformational change in GP that triggers membrane fusion [33]. EBOV mRNA synthesis is detectable at 6–7 h postinfection [34]. The EBOV RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase binds a site within the leader region of each negative‐sense genome and slides along the RNA template, transcribing individual genes sequentially in a 3′ to 5′ direction [35]. Each gene is delineated by highly conserved transcription start and stop signals with polyadenylation sites marking the termini of the mRNAs [20]. Additionally, EBOV mRNAs are shown to be capped at the 5′ end [36]. NP is the most transcribed gene, whereas L is the least transcribed in Vero E6 cells [37]. EBOV transcription is dependent on the presence of transcription factor VP30 [18]. The initial transcription and translation of virus genes leads to a buildup of VPs, especially NP, which triggers viral replication [17, 18]. During replication, the promoter at the 3′ end of the genomic RNA drives synthesis of full‐length, positive‐sense antigenomic RNA, which, in turn, serves as a template for production of progeny negative‐sense genomes [35]. When sufficient levels of negative‐sense genomes and VPs are reached, they are assembled at the plasma membrane, where VP40 induces budding of filoviruses [37] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Ebola virus life cycle. (1) EBOV gains cell entry by receptor‐mediated endocytosis. (2) Acidification of the endocytic vesicle, followed by fusion of the virus and host membranes, releases the EBOV nucleocapsid into the cytoplasm. (3) The RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase transcribes individual mRNA from the negative‐sense genome in a 3′ to 5′ direction. Each mRNA is capped at the 5′ end and contains a poly‐A tail. (4) During replication, the promoter at the 3′ end of the genomic RNA drives synthesis of the full‐length, positive‐sense, antigenomic RNA, which, in turn, serves as a template for the production of progeny, negative‐sense genomes. (5) Nucleocapsid proteins (VP35, L, VP30, and NP) associate with negative‐sense genome progeny, whereas (6) GP and sGP are further modified in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi body. (7) When sufficient levels of the negative‐sense genomes and viral proteins are reached, they are assembled at the plasma membrane with membrane‐associated proteins (matrix proteins VP24 and VP40 and GP). (8) Complete virions bud from the cell surface.

ANIMAL MODELS

Rodent models, including guinea pigs and inbred mice, are not ideal for studying EBOV hemorrhagic fever because both models require the use of a MA‐ZEBOV, which was obtained by serial passage of WT‐ZEBOV in newborn mice [38]. Although lethal infection of mice with MA‐EBOV can be achieved by i.p. injection, no significant coagulation disorders or other characteristics of hemorrhagic fever are observed [39] Clinical manifestations in MA‐EBOV–infected mice include increased inflammatory cytokines, infection of mononuclear phagocytes, lymphopenia, and disseminated viremia, with death occurring 5–7 d postinfection [39]. Compared with WT‐ZEBOV, MA‐EBOV possesses 13 amino acid mutations in VP35 (n = 1), VP24 (n = 1), VP40 (n = 1), GP (n = 3), NP (n = 2), L (n = 3), and noncoding regions (n = 2) [40]. Two amino acid mutations in NP and VP24 are the major determinants of MA‐EBOV virulence in mice [40]. Recently, a new mouse model was developed using the Collaborative Cross resource, a large panel of genetically diverse, recombinant, inbred strains (CC‐RI) derived from a cross of 8 different mice strains, referred to as founders [41]. Different CC‐RI strains can be crossed with one another to generate intercrossed (CC‐RIX) F1 progeny. Rasmussen et al. [42] assessed the pathogenic phenotype following i.p. infection with MA‐EBOV in 47 CC‐RIX lines and observed a spectrum of disease outcomes, including coagulation defects in 16 CC‐RIX lines. However, this model still requires the use of MA‐EBOV. To date, hu‐BLT mice, which are engrafted with human immune cells, are the only rodent model susceptible to WT‐ZEBOV. Although hu‐BLT mice exhibit some features of human EVD, including dysregulation of cytokine and chemokine secretion, this model does not exhibit hemorrhaging and coagulopathies [43].

In contrast, several NHP species are susceptible to the same ZEBOV strains that cause disease in humans, including African green monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops), hamadryad baboons (Papio hamadryas), cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis), and rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) [44]. However, cynomolgus macaques and rhesus macaques are the gold standard animal models used in filovirus study because of the strong resemblance of disease symptoms as well as host responses to those observed in human infections [45, 46]. The macaque model uses a challenge dose and route (1000 PFU; i.m. injection) that reflects a likely laboratory exposure and is uniformly lethal, with animals succumbing to infection 6–7 d after challenge [14]. MA‐EBOV is not virulent in macaques; 2 of 3 rhesus macaques challenged with a large dose of MA‐EBOV (5000 PFU) showed mild illness [39].

SUBVERSION OF INNATE IMMUNE RESPONSE BY EBOV

Although EBOV displays broad tropism, studies in macaques have shown that APCs, notably monocytes, macrophages, and DCs, are the first and preferred targets of EBOV [45, 47] ( Fig. 2 ). Filovirus infection of monocytes and macrophages in vitro triggers the robust expression of inflammatory mediators, including IL‐1β, IL‐6, IL‐8, MIP‐1α, MIP‐1β, MCP‐1, and TNF‐α [48, 49–50]. Increased levels of these inflammatory mediators, in addition to reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, have been detected in the plasma of humans and animal models following EBOV exposure [48, 51, 52, 53, 54–55]. Chemokines released from virus‐infected cells recruit additional monocytes and macrophages to sites of infection, increasing the availability of target cells. Increased inflammatory mediators may also contribute to the impairment of the vascular system and disseminated intravascular coagulation [47, 56, 57–58]. In contrast, in vitro infection of DCs results in their failure to 1) up‐regulate costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80, and CD86 as well as MHC class II; and 2) produce chemokine/cytokines [59, 60]. Because maturation of DCs is essential in inducing an effective, adaptive immune response, EBOV infection may impair the ability of DCs to mature into mobile, APCs that can stimulate T and B cell responses needed to clear infection [61] (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Ebola virus pathogenesis. Ebola virus initially and preferentially infects monocytes, macrophages, and DCs. Infection of DCs impairs their maturation and suppresses type I IFN responses, thereby preventing T cell activation. Infection of monocytes and macrophages leads to the robust expression of inflammatory mediators. Secreted chemokines can recruit more monocytes, which act as new targets for viral infection. Inflammatory mediators, reactive oxygen species, and nitric oxide can induce apoptosis leading to lymphocyte death. The lack of lymphocytes, such as CD4 T cells, inhibits the ability of the virus to induce an Ab response. Production of EBOV secreted glycoprotein (sGP) usurps any GP‐specific Abs that are made. Eventually, the inflammatory cytokines are responsible for vascular leakage. EBOV systemically disseminates to liver, kidneys, adrenal glands, and endothelial cells, which contributes to symptoms associated with hemorrhagic fever.

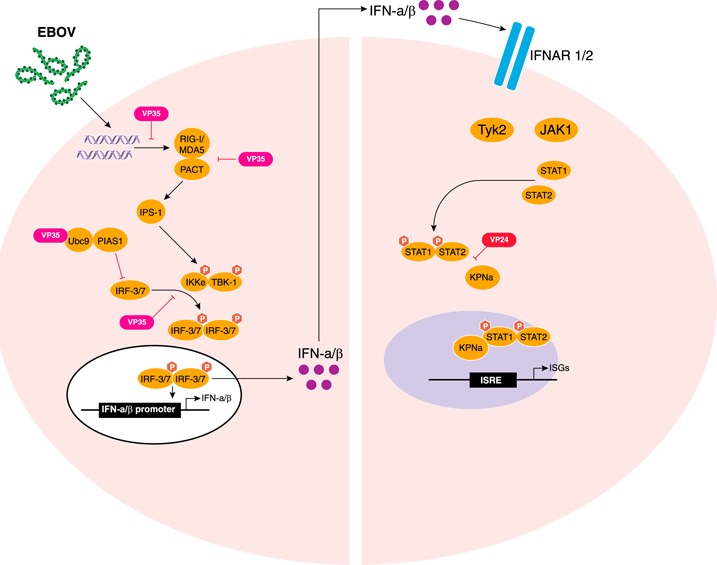

A critical component for innate immunity against viral infection is the IFN response. Viral dsRNA in the cytosol is detected by viral sensors retinoic acid‐inducible gene‐I and melanoma differentiation associated gene‐5 ( Fig. 3 ). Upon activation, RLRs signal through the adaptor molecule IFN‐promoter stimulator‐1, which induces the kinases TBK‐1 and IKKɛ to phosphorylate IRFs 3 and 7. Phosphorylated IRF3/IRF7 dimerize and move to the nucleus, where they activate the transcription of IFN‐β. Binding of IFN‐α/β to receptors IFNAR1/2 activates the JAK and STAT pathways. Phosphorylation of JAK1 by tyrosine kinase 2 leads to phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT2, which then dimerize and translocate to the nucleus, where they activate the transcription of IFN‐stimulated genes (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

EBOV evades type I IFN responses. EBOV can prevent production of and cellular responses to type I IFN. In vitro studies have shown that EBOV VP35 can block RLR signaling by binding to dsRNA or binding PACT, preventing production of IFN‐α/β. VP35 can interact with host SUMOylation machinery, including SUMO E2 enzyme Ubc9 and E3 ligase PIAS1, to promote the degradation of IRF7/IRF3. VP35 can also prevent the phosphorylation of IRF3 by IKKɛ. EBOV VP24 can prevent cellular responses to IFN‐α/β by binding to the nuclear importer protein karyopherin α‐1 (KPNα1), preventing it from binding to phosphorylated STAT1, thus limiting the accumulation of nuclear STAT1 and preventing IFN‐induced gene expression. ISRE, IFN‐stimulated response element.

EBOV can prevent production of, and cellular responses to, type I IFN. In vitro studies have shown that EBOV VP35 can block RLR signaling by binding to dsRNA or binding PACT, thereby preventing production of antiviral cytokines IFN‐α/β [62, 63] (Fig. 3). VP35 can also prevent the phosphorylation of IRF‐3 by IKKɛ [64, 65]. Furthermore, VP35 can interact with host SUMOylation machinery, including SUMO E2 enzyme Ubc9 and E3 ligase PIAS1, to promote the degradation of IRF7/IRF3 [66]. Interestingly, infection of guinea pigs with recombinant ZEBOV possessing 2 point mutations in VP35, which impair its dsRNA binding activity, resulted in loss of virulence and protected animals against subsequent WT‐ZEBOV challenge [67]. EBOV VP24 binds to the nuclear importer protein KPN‐α1 and prevents it from binding to phosphorylated STAT1, thereby limiting the accumulation of nuclear STAT1 and preventing IFN‐induced gene expression [68, 69, 70–71] (Fig. 3).

DYSREGULATED ADAPTIVE IMMUNE RESPONSE AFTER EBOV INFECTION

Severe lymphopenia and destruction of lymphoid tissue is one of the hallmarks of Ebola infection [72] (Fig. 2). Loss of peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as NK cells has been documented in mice [73], cynomolgus macaques [46, 74], and human PBMCs cultures [75] after ZEBOV infection. Loss of B cells is more controversial, with some studies demonstrating apoptosis of B lymphocytes using double‐staining for CD20 and TUNEL in mice and macaques [47], whereas other studies show no changes in B lymphocyte counts in cynomolgus macaques [74]. In vivo and in vitro studies using TUNEL staining and transmission electron microscopy confirm apoptosis as the main mechanism of lymphocyte loss during ZEBOV infection [47]. In humans, percentages of peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing the apoptotic marker CD95 were greater in fatally infected patients compared with healthy individuals [55]. Increased expression of CD95 was also observed in cynomolgus macaques [74].

Increased levels of soluble Fas and 41/7 nuclear matrix protein, which is cleaved and solubilized during apoptosis, have been detected in plasma of patients during the last 5 d of life after infection with ZEBOV [76]. Similarly, an up‐regulation of Fas and Fas‐ligand mRNA levels was detected using RT‐PCR in PBMCs of infected patients [76]. Moreover, mice deficient in the expression of Fas‐associated death domain or overexpressing the antiapoptotic molecule BCL2 were resistant to MA‐EBOV–induced lymphocyte apoptosis, suggesting lymphocyte death can occur via both extrinsic (death receptor) and intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathways [77]. Furthermore, although patients who survived ZEBOV infection showed an up‐regulation of BCL2 mRNA in PBMCs, those who succumbed showed a significant decrease of BCL2 mRNA expression during the terminal stage of infection [76]. The decreased expression of BCL2 was coincident with the loss of CD3, CD8, and T cell receptor β chain variable region mRNA in PBMCs [76].

However, infection of human PBMCs in vitro with ZEBOV did not result in increased expression of Fas but rather an increase in mRNA levels of TRAIL in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at 7 d postinfection [75]. These data suggest that additional inflammatory mediators released in vivo during infection result in the increased Fas expression and that apoptosis of lymphocytes during ZEBOV infection is not due to viral replication (Fig. 2). Indeed, analysis of ZEBOV‐infected NHP tissues clearly showed the presence of EBOV antigens within the mononuclear phagocytic cells but not in the lymphocytes, even after in vitro infection [47, 57]. Some inflammatory mediators produced after ZEBOV infection, such as TNF‐α, nitric oxide, and reactive oxygen species, can induce apoptosis [78, 79–80]. Moreover, 90% of ZEBOV‐infected, adherent human macrophages were positive for TRAIL by immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, and RNA analysis [48] and can, therefore, induce apoptosis in lymphocytes via the extrinsic pathway.

The lymphopenia observed during an EBOV infection in part explains the lack of EBOV‐specific T and B cell responses. The lack of T cell response is evident by the absence of T cell–derived cytokines (IL‐2, IL‐3, IL‐4, IL‐5, IL‐9, IL‐13) in the plasma of fatally infected patients [55, 60, 81, 82]. In addition, lack of activated T lymphocytes was reported in the peripheral blood of ZEBOV‐infected macaques [59, 74] and mice [83]. Because CD4+ T cells are required for B cell isotype class switching, the loss of CD4+ T cells may explain the lack of Ebola‐specific IgM and IgG Abs observed in fatally infected patients [76]. Moreover, the EBOV envelope is covered in a dense concentration of N‐ and O‐linked glycans [84, 85], which interfere with binding of neutralizing Abs [86, 87–88]. Finally, secreted GPs, which account for about 70% of GP mRNA transcripts [89], act as decoys that usurp the much‐needed neutralizing Abs [90] (Fig. 2). Subversion of the adaptive immune response, coupled with inactivation of the innate immune branch, allows EBOV to disseminate systemically.

The magnitude of the recent ZEBOV epidemic and the large number of survivors has provided a unique opportunity to study host immune responses in patients with EVD who survived infection. Four patients treated at Emory Hospital with various combinations of the Ab cocktail Zmapp (Mapp Biopharmaceutical, San Diego, CA, USA), an siRNA against ZEBOV, a DNA polymerase inhibitor, and convalescent serum as early as 1 d and as late as 10 d after symptom onset exhibited increased frequencies of activated CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, and plasmablasts 2–3 wk after the onset of symptoms. Lymphocyte activation coincided with a decline in viral loads during the second week, which reached its nadir by wk 3 after symptom onset [91]. EBOV‐specific IgG responses peaked 2–3 wk after symptom onset, and the strongest T cell responses were directed against ZEBOV NP. Surprisingly, the number of activated T cells remained elevated up to 30 d after discharge, suggesting potential persistence of ZEBOV antigen [91]. A second study of T cell immune responses in patients with EVD, managed at the Ebola Treatment Centers in Guinea (n = 47 in Guéckédou; n = 157 in Coyah), showed that, although there was robust CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation (measured by coexpression of CD38 and HLA‐DR) in all EVD cases, an increase in the coexpression of the negative T cell regulators CTLA‐4 and PD‐1 significantly correlated with fatalities [92]. These studies indicate that dysregulation of the T cell response, in addition to lymphopenia, contributes to EVD pathology.

VASCULAR PERMEABILITY AND COAGULATION DEFECTS

In addition to inducing apoptosis within lymphocytes, the large release of TNF‐α from infected monocytes/macrophages can increase endothelial permeability, resulting in vascular leakage [48]. In vitro studies show that increased endothelial permeability is temporally associated with the release of TNF‐α from MARV‐infected human monocytes/macrophages [93]. Similarly, the release of nitric oxide, which is an important effector molecule in the homeostasis of the cardiovascular system, can result in the loss of vascular smooth‐muscle tone and hypotension [53, 94]. In addition, ZEBOV infection of macrophages leads to the up‐regulation of surface TF as well as the release of membrane microparticles containing TF, resulting in the overactivation of the extrinsic pathway of coagulation and the development of disseminated intravascular coagulation [58]. Expression of TF is further up‐regulated by proinflammatory cytokines, notably IL‐6, which are abundant during acute ZEBOV infection, exacerbating the intravascular coagulation phenotype [95].

In addition, ZEBOV‐induced paralysis of the host response facilitates viral dissemination to hepatocytes, adrenal cortical cells, and endothelial cells of connective tissue in cynomolgus macaques [45] (Fig. 2). Hepatocellular necrosis results in decreased synthesis of coagulation proteins, whereas infection and necrosis of adrenocortical cells may negatively affect blood pressure homeostasis, leading to hemorrhage [45]. Coagulation abnormalities are initiated early during ZEBOV infection in cynomolgus macaques. Specifically, a dramatic decrease in plasma levels of anticoagulant protein C occurs as early as 2 d postinfection. This is followed by an increase of both tissue plasminogen activator, which is involved in dissolving blood clots, and fibrin‐degradation products (d‐dimers) at d 5 postinfection [58]. Thrombocytopenia and prolonged prothrombin time are indicators of dysregulated blood coagulation and fibrinolysis during ZEBOV infection and may manifest as petechiae, ecchymoses, mucosal hemorrhages, and congestion [39, 58]. Toward the terminal stage of the infection, and after the onset of hemorrhagic abnormalities, ZEBOV replicates in endothelial cells [46]. However, although infection of endothelial cells is thought to have a role in the pathogenesis, the molecular mechanisms of endothelial damage are not yet fully understood.

LONG‐TERM HEALTH OUTCOMES IN EBOV SURVIVORS

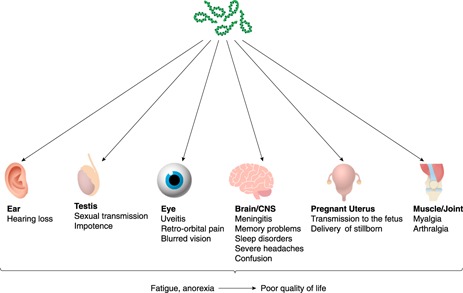

The recent ZEBOV outbreak in West Africa resulted in an unprecedented number of survivors (∼17,000) and highlighted the complexity of EVD sequelae in clinically recovered patients ( Fig. 4 ). One retrospective study collected health status, functional limitations, demographics, blood chemistry, hematology, and filovirus Ab titers from 49 survivors and 157 seronegative contacts, 29 mo after the 2007 Bundibugyo outbreak in Uganda. Results showed that, although no differences in blood analysis were observed, survivors were at a significantly greater risk for ocular problems (retro‐orbital pain and blurred vision), loss of hearing, difficulty swallowing, difficulty sleeping, arthralgia, abdominal and back pain, fatigue, impotence, severe headaches, memory problems, and confusion [96]. More recently, a study in which clinical and laboratory records of surviving patients treated in Port Loko, Sierra Leone, were assessed showed a higher incidence of arthralgia, ocular symptoms (including uveitis), and auditory problems. Moreover, a higher ZEBOV viral load at clinical presentation was associated with a higher incidence of uveitis and other ocular symptoms [97]. A second study of surviving patients showed increased incidence of anorexia, arthralgia, myalgia, and chest/back pain [98] (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Long‐term post‐EBOV consequences. EBOV entry and persistence into organs that are immune privileged, including the ear, testis, eye, CNS, pregnant uterus, and muscle tissue, have been observed in clinically recovered patients, resulting in Ebola disease sequelae.

Further investigation of recovering survivors revealed that ZEBOV persists in the semen, ocular fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, placenta, and amniotic fluid. A study of 93 male survivors in Sierra Leone showed that 100% of men (n = 9) who provided a semen specimen 2–3 mo after the onset of EVD had positive qRT‐PCR results despite absence of viremia. Of 40 samples obtained 4‐6 mo after onset, 26 tested positive (65%), whereas 11 of 43 specimens (26%) collected at 7–9 mo after onset were positive [99]. Recently, genetic sequencing of ZEBOV strain confirmed a female patient acquired Ebola virus via sexual transmission from a survivor whose semen tested positive for ZEBOV by qRT‐PCR 199 d after his recovery [100]. These data suggest that infectious virus, not only viral RNA, can persist in the semen for months after viremia ceases. In one case, although a tear‐film specimen and peripheral blood tested negative for ZEBOV RNA by qRT‐PCR, virus was detected in the aqueous humor 9 wk after blood and urine tested negative for ZEBOV by qRT‐PCR [101]. ZEBOV was also detected in the cerebral spinal fluid of a nurse who developed meningitis 9 mo after recovery from EVD [102]. Finally, ZEBOV persisted in amniotic fluid and placenta after clearance from the blood in 2 pregnant women, resulting in the delivery of stillborn fetuses in both cases [103].

Collectively, these observations indicate that ZEBOV can persist in organs that were traditionally considered immune‐privileged sites (Fig. 4). The ability of immune cells to access these sites (anterior chamber of the eye, central nervous system, testes, and pregnant uterus) is limited to reduce the risk of irreparable damage to these critical organ system [104]. The persistence of ZEBOV in these sites well after recovery raises many questions regarding the mechanisms and the kinetics by which this virus gains access to, and is able to persist in, these sites.

CLINICAL CORRELATES AND HOST FACTORS THAT PREDICT DISEASE OUTCOME

It is currently not well understood why some patients develop fulminant EVD and succumb to infection whereas others survive. The recent outbreak provided an opportunity to address this critical question using large patient cohorts. One of the strongest predictors of outcome was the initial viral load at the time of admission. Patients who succumbed to disease presented with, on average, a 2‐log10 greater genome equivalents/ml than did those who survived [105]. Association between initial viral load and disease outcome was also reported by the Jui Government Hospital in Sierra Leone, who showed that patients who were admitted with a viral load >106 copies/ml had significantly shorter survival times than did patients with viral loads <106 copies/ml. Moreover, advanced age was significantly and negatively associated with survival [81, 106]. These observations were confirmed in a second study in which patients with EVD younger than 21 y had a lower CFR than did those older than 45 y [107]. From a clinical perspective, aspartate aminotransferase (but not ALT) and d‐dimer levels are important prognostic factors in EBOV disease [108].

NPC1 and HSPA5 have also been identified as host factors that can modulate severity of ZEBOV infection. NPC1 is an endo/lysosomal cholesterol transporter protein that can affect endosome/lysosome fusion. Administration of U18666A, a small molecule that targets NPC1, to Vero and HAP1 cells inhibited infection by rVSV‐ZEBOV GPs. Knockout of NPC1 in HAP1 cells also had significantly lower amount of cellular infection by rVSV‐ZEBOV GPs, suggesting that membrane fusion and entry mediated by ZEBOV GPs require NPC1 [109]. HSPA5 is an endoplasmic reticulum chaperone that may have an important role in the maturation of viral proteins. Administration of the HSPA5 inhibitor epigallocatechin gallate to HeLa cells before infection results in a significant decrease in viral infection. Similarly, transfection of 293 T cells with siRNA targeting HSPA5 before ZEBOV infection resulted in a significant drop in viral transcription and VP24/VP40 protein levels. Lastly, in vivo targeting of HSPA5 using PMOs in mice (C57BL/6) before MA‐EBOV challenge resulted in increased survival rates [110].

Liquid chromatography‐linked tandem mass spectrometry of purified ZEBOV and MARV virions produced in Vero E6 cells identified 66 virion‐associated host proteins; 53 of which were identified only in Ebola virions. Virion‐associated host proteins were involved in cell adhesion, cytoskeleton formation, cell signaling, intracellular trafficking, membrane organization, and protein folding [111]. Spurgers et al. [111] examined the biologic relevance of these host proteins by performing an siRNA library‐mediated knockdown of gene expression in 293 T cells followed by ZEBOV or MARV infection 24 h later. They identified 11 genes that influence viral replication as measured by qRT‐PCR. Knockdown of HSPA5, RPL18, UBC, RPL3, RPL5, RPS6, DNAJB2, and HIST1H2BO reduced ZEBOV infection, whereas knockdown of HSPB1, dermcidin, and ADP‐ribosylation factor 1 increased infectivity rates. In line with the proteomics data, knockdown of only HSPA5, RPL18, and UBC reduced MARV infectivity [111].

Following the SEBOV Uganda outbreak in 2000–2001, HLA‐B typing was performed using leukocytes isolated from 77 patients (n = 35 survivors; n = 42 fatalities) to determine whether the MHC class I genes of infected patients could influence the course of disease, using predictive discriminant analysis and epitope‐prediction software [112]. Alleles B*07, B*14, B*35, and B*40 were associated with patient survival. In contrast, alleles B*67, B*13, and B*42 were associated with fatal outcomes. Epitopes predicted to bind strongly to HLA B07 were identified within the L polymerase, NP, and VP35 proteins [112]. Another study evaluated the association of KIRs with the outcome of human ZEBOV infection. KIRs are expressed on the surface of NK cells and bind to HLA class I alleles to either activate or inhibit NK cell function. A χ2 test and a Fisher's exact test were used to compare KIRs among 4 populations: 1) n = 54 controls from rural regions of Gabon, who were seronegative for ZEBOV‐specific IgG; 2) n = 68 healthy subjects, who were seropositive for ZEBOV‐specific IgG and defined as contacts; 3) n = 21 survivors of ZEBOV infection (outbreaks in Gabon from 1996–2001); and 4) n = 15 fatalities of ZEBOV infection (from epidemics in Gabon from 2001–2002). Results showed that only 9.5% of survivors, compared with 35.2% of controls, had the activating KIR2DS3 gene, suggesting that the KIR2 family may be associated with EBOV fatal outcome. More important, activating KIR2S1 and KIR2DS3 were significantly more frequent in fatalities (46.8% and 53.3%, respectively) than they were in survivors (4.6% and 9.5%, respectively) [113].

VACCINES AGAINST EBOV

Several vaccine platforms against EBOV have been developed, including viral protein antigen‐based vaccines (virus‐like particles), replication‐deficient vaccines (DNA vaccines and rAds), and replication‐competent recombinant viral vector–based platforms (recombinant human parainfluenza virus, recombinant rabies virus, recombinant CMV, and rVSV) [114]. Among these various vaccine strategies, 2 vaccine candidates have advanced the furthest in clinical trials: rAd and rVSV vectors expressing GP.

Recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 expressing the ZEBOV GP gene (rAd5‐EBOV‐GP) is a replication‐deficient vector. Immunization of cynomolgus macaques with a single dose of 1010 rAd5‐EBOV‐GP particles resulted in the production of ZEBOV‐GP–specific Abs and GP‐specific CD8+ T cells and provided 100% protection against ZEBOV challenge 21 d after vaccination [115]. Passive transfer of ZEBOV‐specific IgG, purified from NHPs vaccinated with DNA and rAd5 vectors expressing ZEBOV GP before ZEBOV challenge only protected 25% of naïve animals. In contrast, CD8+ T cell depletion of NHPs immunized with rAd5‐EBOV‐GP 4 d before challenge resulted in 80% mortality, suggesting a major role for CD8+ T cells in mediating protection in this vaccine platform [116]. However, a large percentage of humans have preexisting immunity against Ad5, which interferes with the efficacy of the rAd5‐EBOV‐GP vaccine. Indeed, individuals with anti‐Ad5 Abs generated lower GP‐specific humoral responses after rAd5‐EBOV‐GP vaccination compared with Ad5‐seronegative subjects [117, 118].

To address this challenge, alternate rAd‐based vaccine platforms were explored. Recombinant Ad26 and Ad35, which have lower seroprevalence in humans, can engender GP‐specific T and B cell responses after 2 vaccinations and provide 100% protection in NHPs against ZEBOV infection [119]. Immunization of cynomolgus macaques with a single inoculation of recombinant ChAd3 expressing ZEBOV GP (rChAd3‐EBOV‐GP) resulted in complete protection when ZEBOV challenge occurred 5 wk after vaccination but only 50% protection when the animals were challenged 10 mo after immunization [120]. The addition of a booster vaccination using recombinant modified vaccinia Ankara expressing EBOV‐GP 8 wk after the rChAd3‐EBOV‐GP vaccination resulted in complete protection at 10 mo [120]. In September 2014, 2 phase I clinical trials conducted by the NIAID and Welcome Trust evaluated the rChAd3‐EBOV‐GP safety and immunogenicity in 80 participants in a dose‐escalation design. Reactivity and immunogenicity to rChAd3 was dose dependent [121], but Ab and T cell responses were lower compared with those associated with protection in macaques [122]. This vaccine platform has entered a phase II/III trial sponsored by the NIAID called Partnership for Research on Ebola Vaccines in Liberia, which will enroll 27,000 healthy adults and is estimated to be completed in June 2016 [123].

Replicating vaccine platforms have several advantages over nonreplicating ones, including longer durability, but they also have several challenges, such as risk of reversion to WT and potential adverse events in patients with deficient or compromised immunity. VSV is a member of the Rhabdoviridae family with a nonsegmented, negative‐stranded RNA genome. A single vaccination with only 107 PFU rVSV‐ZEBOV‐GP for NHPs and 2 PFU for mice provided complete protection against ZEBOV challenge 28 d later [124, 125]. A single dose of rVSV‐ZEBOV‐GP confers complete protection against EBOV infection for up to 6 mo in macaques and 18 mo in mice and guinea pigs [126, 127]. Moreover, this vaccine platform confers complete protection in macaques against MARV challenge as late as 14 mo after vaccination, further demonstrating the durability of this vaccine platform against filoviruses [128]. In contrast to rAd‐based vaccines, Ab responses are the main mode of protection conferred by rVSV‐ZEBOV‐GP [129]. In a NHP study in which groups of cynomolgus macaques were either depleted of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells during vaccination or depleted of CD4+ T cells during challenge, only the animals depleted of CD4+ T cells during vaccination and which lacked GP‐specific Abs succumbed to ZEBOV challenge 28 d after immunization [129].

Because rVSV‐ZEBOV‐GP is a live‐attenuated, replicating virus, several studies have investigated its safety. No adverse events have been observed in >80 NHPs immunized with rVSV‐MARV‐GP or rVSV‐ZEBOV‐GP [124, 130]. Moreover, no evidence of disease was observed in immunocompromised animal models (NOD‐SCID mice and SHIV rhesus macaques), further confirming the safety of this vaccine [125, 130]. Vaccination of cynomolgus macaques with a mixture containing rVSV‐MARV‐GP, rVSV‐ZEBOV‐GP, and rVSV‐SEBOV‐GP resulted in protection after infection with MARV, ZEBOV, SEBOV, and CIEBOV, indicating that a multivalent rVSV vaccine is efficacious [131]. Finally, rVSV‐ZEBOV‐GP was effective postexposure and conferred 50% and 100% protection in rhesus macaques given rVSV‐ZEBOV‐GP or rVSV‐SEBOV‐GP, respectively, when administered 20–30 min after challenge [132, 133]. More recently, complete and partial protection was achieved when cynomolgus macaques were immunized with rVSV‐ZEBOV‐GP at 7 and 3 d before challenge with the 2014 strain Makona, respectively. Because these animals lacked detectable ZEBOV‐GP specific Abs at the time of challenge, these data suggest that early innate immune responses to this vaccine can provide rapid protection [134].

Multiple phase I clinical trials across Europe and Africa have evaluated the safety and immunogenicity of this vaccine platform. Data from these studies show this vaccine to be safe and immunogenic [135, 136]. More important, results from a cluster‐randomized ring phase III trial, in which 7,651 people were vaccinated with 2 × 107 PFU of rVSV‐ZEBOV‐GP, showed this vaccine to be 100% efficacious [137]. Importantly, as described for macaques, this vaccine has the potential to be a successful postexposure treatment option in humans. In March 2009, a single dose of rVSV‐ZEBOV‐GP was administered to a virologist 48 h after an EBOV needle‐stick injury. The subject developed acute fever and rVSV viremia but did not develop EVD [138]. Similarly, during the 2014 outbreak, a physician who sustained a needle‐stick injury while working in an Ebola treatment unit in Sierra Leone was given rVSV‐ZEBOV‐GP as an emergency postexposure vaccination 43 h later. The patient developed a self‐limited febrile syndrome, in addition to ZEBOV‐GP–specific adaptive immune responses following vaccination, and recovered [139]. Although these 2 promising vaccine candidates have been accelerated for clinical trials, correlates and durability of protection in humans remain to be determined.

THERAPEUTICS AGAINST EBOV

Strategies for developing experimental, postexposure treatments against EBOV focus on 1) preventing the development of filovirus‐associated coagulopathies (recombinant nematode anticoagulant protein and recombinant human activated protein C); 2) inhibiting viral replication or translation, such as nucleotide analogs (Favipiravir [Toyama Chemical, Tokyo, Japan], BCX4430 [BioCryst Pharmaceuticals, Durham, NC, USA], Brincidofovir [Chimerix, Durham, NC, USA]) and antisense therapeutics (PMOs and siRNA); or 3) limiting viremia and virus spread (mAb cocktails). Several of these postexposure therapeutic candidates are currently in clinical trials.

Favipiravir (T‐705), developed by Toyama Chemical, is an oral nucleotide analog that has been licensed for the treatment of influenza. It inhibits viral RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase by directly competing with GTP after it is converted to its active metabolite form (ribofuranosyl triphosphate). Favipiravir has been shown to suppress ZEBOV replication in Vero E6 cells when added 1 h after infection [140]. Favipiravir is also effective when given 1 h after ZEBOV aerosol challenge in immunodeficient IFN‐α/β receptor knockout (IFNAR−/−) mice for 14 d [141]. To date, Favipiravir has been used to treat 1 French nurse infected with Ebola in the 2014–2015 outbreak who recovered [142]. A nonrandomized phase II clinical trial tested the efficacy of Favipiravir in 126 patients with EVD in Guinea. Of these 126, 111 were analyzed and divided into 3 groups: 1) n = 55 who had a baseline Ct ≥ 20 (5 × 107 genome copies/ml); 2) n = 44 with Ct < 20; and 3) n = 12 young children between 1–6 y old (median Ct value of 19.9). All groups received Favipiravir within a median of 4 d from the first symptoms. Sixty participants died, with 20% mortality in the group with Ct ≥ 20, 90% mortality in the group with Ct < 20, and 75% mortality in the group of young children. These data show that initial viral load and age were predictors of EVD outcome. The 51 surviving patients had mean initial viral loads of 6.65 log10 copies/ml, with a mean decrease of 0.33 log10 copies/ml/d after Favipiravir initiation. Moreover, the trial showed the antiviral was well tolerated, and of the 99 adults and adolescents, viral loads and mortality were not significantly different in patients who received Favipiravir <72 h from symptom onset than patients who received treatment >3 d from symptom onset [143].

BCX4430 is an adenosine analog that is incorporated into the nascent viral RNA chain and terminates transcription. Similar to Favipiravir, it is not incorporated into mammalian RNA or DNA. Treatment of cynomolgus macaques with BCX4430 as late as 48 h after MARV challenge conferred 100% protection [144]. BioCryst Pharmaceuticals and NIAID have initiated a phase I clinical trial of BCX4430 in the United Kingdom [145]. Brincidofovir (CMX001), developed by Chimerix, is a lipid conjugate of cidofovir (known to inhibit replication of DNA viruses, including cytomegalovirus and adenovirus) that inhibits ZEBOV replication in vitro, although the mechanism is unknown [146]. Because of the few new EVD cases, a clinical trial study of Brincidofovir has been terminated [147]. Warren et al. [148] has reported a novel nucleoside triphosphate, GS‐5734, which exhibits antiviral activity against ZEBOV and provided 100% protection in 12 infected rhesus macaques administered a daily 10 mg/kg starting 2 or 3 d postexposure for 12 d. Importantly, when administered i.v., GS‐5734 was able to reach immune privileged sites, including testes, eyes, and brain.

PMOs are synthetic antisense molecules that target mRNA in a sequence‐specific manner and suppress translation through steric hindrance rather than targeting mRNA for degradation. AVI‐6002 (Sarepta Therapeutics, Cambridge, MA, USA) consists of PMO AVI‐7537 (Sarepta Therapeutics) and AVI‐7539 (Sarepta Therapeutics), which target VP24 and VP35, respectively. AVI‐6002 protected 62.5% of rhesus macaques when given 30–60 min after ZEBOV infection and daily for 14 d [149]. Interestingly, treatment with AVI‐7537 alone protected 6 of 8 cynomolgus macaques when administered 1.5 h after ZEBOV challenge and daily for 14 d, whereas treatment with AVI‐7539 alone did not [144, 150]. Data from phase I clinical trial revealed that AVI‐6002 was safe, with doses ranging from 0.05 to 4.5 mg/kg [150].

SNALPs were developed to deliver siRNAs in vivo, and this combination has been shown to efficiently target the ZEBOV polymerase L gene, resulting in complete protection of guinea pigs when given daily starting 1 h after challenge [151]. TKM‐Ebola, developed by Tekmira Pharmaceuticals (Burnaby, BC, Canada), which consists of SNALP carrying siRNAs that target ZEBOV L polymerase, VP24, and VP35 protected 2 of 3 macaques when given 30 min after challenge and daily thereafter [152]. Although TKM‐Ebola entered phase I trials early in 2014, studies were halted when elevated cytokine levels were observed in healthy participants. The FDA, however, has extended access to TKM‐Ebola in a state of emergency [153].

Based on experimental and clinical data supporting the importance of Ab‐mediated protection against EBOV infections, monoclonal treatment strategies were developed. Initial studies that used mAbs showed very limited success, if any. The human mAb, KZ52, which targets an epitope in ZEBOV‐GP failed to protect rhesus macaques against ZEBOV challenge when administered 1 d before and 4 d after challenge [154]. However, when a combination of 2 human–mouse chimeric neutralizing mAbs was given to 3 NHPs 1 d before and 1 and 3 d after ZEBOV challenge, 1 of 3 was protected and another animal had delayed time to death [155]. Furthermore, passive transfer of polyclonal IgG isolated from vaccinated NHPs that survived ZEBOV or MARV challenge as late as 48 h after infection protected naïve macaques against both MARV and ZEBOV challenge [156]. These studies strongly indicated that protection against EBOV requires targeting of multiple epitopes on GP and that neutralization potential may not be a good predictor of protection.

To test this hypothesis, several ZEBOV GP‐specific mAbs produced after rVSV‐ZEBOV‐GP vaccination were evaluated in immunocompetent mice and guinea pigs individually or as pools. As previously described, individually administered mAbs were ineffective, whereas pools of 3 mAbs provided complete protection when administered as late as 2 d postinfection [157]. These studies eventually led to the development of 2 cocktails of mAbs termed MB‐003 (clones c13C6, h13F6, and c6D8) and ZMab (clones m1H3, m2G4 and m4G7). These cocktails conferred protection to NHPs when given as late as 3 d post EBOV challenge [158]. ZMapp, developed jointly by the Public Health Agency of Canada (Ottawa, ON, Canada) and Mapp Biopharmaceuticals (San Diego, CA, USA) contains the monoclonal Abs from MB‐003 and ZMab with the highest efficacy (c13C6, c2G4 and c4G7). Three doses of ZMapp (Defyrus, Toronto, ON, Canada) spread evenly over 9 d, protected NHPs, even when administered 5 d postexposure and after the appearance of clinical symptoms [159]. During the 2014–2015 outbreak, ZMapp was used to treat 7 patients with ZEBOV; 5 of whom survived [160]. In February 2015, NIAID initiated phase I clinical trials of ZMapp. Two hundred patients positive for ZEBOV RNA are to be randomly assigned to a control group, who will receive the current standard of care, and a second group will receive 3 infusions of ZMapp administered 3 d apart [161]. However, the slow production of Abs in tobacco plants has delayed the clinical evaluation of this treatment. The trial is currently still recruiting patients, however, with fewer cases, evaluation of the efficacy of this treatment will be a challenge. New methods to increase yields of the mAb cocktail are being developed. MIL‐77 (developed by Mabworks Biotech Co. [Beijing, China]) is a cocktail of the same Abs used for Zmapp, generated in CHO cells. Although there are currently no efficacy data in monkeys, the WHO reports MIL‐77 is comparable to ZMapp in conferring protection in NHPs after EBOV infection [162, 163]. To date, only 1 mAb—mAb114 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA)—has been shown to fully protect 3 rhesus macaques when given as late as 5 d after ZEBOV challenge [164]. Structural studies show that mAb114 interacts with the glycan cap of GP, inhibiting the binding of cleaved GP to its receptor [165].

CONCLUSION

Although great strides have been made in elucidating the mechanisms of immune evasion by filoviruses, fundamental questions still remain, which are summarized in Table 1 . For instance, insights into how Ebola disables innate immunity have been mostly obtained through in vitro studies. Thus, the effect of EBOV infection of monocytes/macrophages and DCs in vivo remains poorly understood. Furthermore, gene expression studies conducted in NHPs have largely focused on transcriptional changes during the final stages of disease using a lethal EBOV challenge model. Thus, we need to develop a model with partial survival that allows us to identify predictors/genetic signatures of disease outcome early during infection as well as to determine mechanisms of viral persistence and disease sequelae in survivors.

Table 1.

Summary of the current state of the field about EBOV pathogenesis and outstanding questions of basic research

| Lessons learned | Outstanding questions |

| The virulence of Ebola virus is dependent on the species and the strain. | Which viral genes contribute to the differences in virulence? |

| By comparing genomes of different species and different ZEBOV strains, what can we learn about the mechanisms of virulence and what contributed to an outbreak in West Africa? | |

| Based on in vitro studies, ZEBOV infection of monocytes results in excessive inflammatory response that contributes to hemorrhagic fever, whereas infection of DCs results in suppression of DC maturation and type I IFN response. | What is the effect of ZEBOV infection on monocytes and DCs in vivo? |

| What is the role of VP24 and VP35 in the evasion of innate immune responses in vivo? | |

| Lymphopenia and the lack of ZEBOV‐specific cellular and humoral responses are hallmark characteristics of EVD. | Is the subversion of the adaptive immune response determined by the outcome of ZEBOV subversion of innate immunity in vivo? |

| In survivors, ZEBOV persists in immune privileged sites that may contribute to the Ebola disease sequelae observed. | How does ZEBOV gain access to immune privileged sites, and what cell types could be supporting viral replication? |

| What are the mechanisms of viral persistence? | |

| Are the Abs produced from survivors reactive across >1 strain of Ebola virus? | |

| Clinical correlates and host genetics may determine outcome of EBOV infection. | Are there early changes in gene expression in the host after infection that are predictive of disease outcome? |

| Two vaccine platforms, rVSV and rAd, have been shown to be safe and efficacious in clinical trials. | What is the duration of immunity following vaccination? |

| What are the correlates of protection compared with the surrogates of protection? | |

| Antivirals that inhibit EBOV replication or translation or limit virus spread have entered clinical trials. | Do we need new therapies to clear EBOV from immune privileged sites? |

| What alternative routes of administration can be used to target EBOV in immune privileged sites? |

AUTHORSHIP

The review was written by A.R. and I.M.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health Grant 5U19A109945‐02.

References

- 1. Feldmann, H. , Slenczka, W. , Klenk, H. D. (1996) Emerging and reemerging of filoviruses. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 11, 77–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Slenczka, W. , Klenk, H. D. (2007) Forty years of Marburg virus. J. Infect. Dis. 196 (Suppl 2), S131–S135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Siegert, R. , Shu, H. L. , Slenczka, W. , Peters, D. , Müller, G. (1967) On the etiology of an unknown human infection originating from monkeys [in German]. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 92, 2341–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Towner, J. S. , Khristova, M. L. , Sealy, T. K. , Vincent, M. J. , Erickson, B. R. , Bawiec, D. A. , Hartman, A. L. , Comer, J. A. , Zaki, S. R. , Ströher, U. , Gomes da Silva, F. , del Castillo, F. , Rollin, P. E. , Ksiazek, T. G. , Nichol, S. T. (2006) Marburgvirus genomics and association with a large hemorrhagic fever outbreak in Angola. J. Virol. 80, 6497–6516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bausch, D. G. , Nichol, S. T. , Muyembe‐Tamfum, J. J. , Borchert, M. , Rollin, P. E. , Sleurs, H. , Campbell, P. , Tshioko, F. K. , Roth, C. , Colebunders, R. , Pirard, P. , Mardel, S. , Olinda, L. A. , Zeller, H. , Tshomba, A. , Kulidri, A. , Libande, M. L. , Mulangu, S. , Formenty, P. , Grein, T. , Leirs, H. , Braack, L. , Ksiazek, T. , Zaki, S. , Bowen, M. D. , Smit, S. B. , Leman, P. A. , Burt, F. J. , Kemp, A. , Swanepoel, R. ; International Scientific and Technical Committee for Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever Control in the Democratic Republic of the Congo . (2006) Marburg hemorrhagic fever associated with multiple genetic lineages of virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 909–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnson, K. M. , Lange, J. V. , Webb, P. A. , Murphy, F. A. (1977) Isolation and partial characterisation of a new virus causing acute haemorrhagic fever in Zaire. Lancet 1, 569–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jahrling, P. B. , Geisbert, T. W. , Dalgard, D. W. , Johnson, E. D. , Ksiazek, T. G. , Hall, W. C. , Peters, C. J. (1990) Preliminary report: isolation of Ebola virus from monkeys imported to USA. Lancet 335, 502–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Formenty, P. , Hatz, C. , Le Guenno, B. , Stoll, A. , Rogenmoser, P. , Widmer, A. (1999) Human infection due to Ebola virus, subtype CoCte d'Ivoire: clinical and biologic presentation. J. Infect. Dis. 179 (Suppl 1), S48–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Outbreaks chronology: Ebola virus disease. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/history/chronology.html. Accessed January 2, 2015.

- 10. Marzi, A. , Feldmann, F. , Hanley, P. W. , Scott, D. P. , Günther, S. , Feldmann, H. (2015) Delayed disease progression in cynomolgus macaques infected with Ebola virus Makona strain. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 21, 1777–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dowell, S. F. , Mukunu, R. , Ksiazek, T. G. , Khan, A. S. , Rollin, P. E. , Peters, C. J. (1999) Transmission of Ebola hemorrhagic fever: a study of risk factors in family members, Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. Commission de Lutte contre les Epidémies à Kikwit. J. Infect. Dis. 179 (Suppl 1), S87–S91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Feldmann, H. , Geisbert, T. W. (2011) Ebola haemorrhagic fever. Lancet 377, 849–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bwaka, M. A. , Bonnet, M. J. , Calain, P. , Colebunders, R. , De Roo, A. , Guimard, Y. , Katwiki, K. R. , Kibadi, K. , Kipasa, M. A. , Kuvula, K. J. , Mapanda, B. B. , Massamba, M. , Mupapa, K. D. , Muyembe‐Tamfum, J. J. , Ndaberey, E. , Peters, C. J. , Rollin, P. E. , Van den Enden, E. , Van den Enden, E. (1999) Ebola hemorrhagic fever in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo: clinical observations in 103 patients. J. Infect. Dis. 179 (Suppl 1), S1–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Knipe, D. M. , Howley, P. M. (2013) Fields Virology. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kiley, M. P. , Bowen, E. T. , Eddy, G. A. , Isaäcson, M. , Johnson, K. M. , McCormick, J. B. , Murphy, F. A. , Pattyn, S. R. , Peters, D. , Prozesky, O. W. , Regnery, R. L. , Simpson, D. I. , Slenczka, W. , Sureau, P. , van der Groen, G. , Webb, P. A. , Wulff, H. (1982) Filoviridae: a taxonomic home for Marburg and Ebola viruses? Intervirology 18, 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Crary, S. M. , Towner, J. S. , Honig, J. E. , Shoemaker, T. R. , Nichol, S. T. (2003) Analysis of the role of predicted RNA secondary structures in Ebola virus replication. Virology 306, 210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mühlberger, E. , Lötfering, B. , Klenk, H. D. , Becker, S. (1998) Three of the four nucleocapsid proteins of Marburg virus, NP, VP35, and L, are sufficient to mediate replication and transcription of Marburg virus‐specific monocistronic minigenomes. J. Virol. 72, 8756–8764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mühlberger, E. , Weik, M. , Volchkov, V. E. , Klenk, H. D. , Becker, S. (1999) Comparison of the transcription and replication strategies of Marburg virus and Ebola virus by using artificial replication systems. J. Virol. 73, 2333–2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kawaoka, Y. (2005) How Ebola virus infects cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 2645–2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sanchez, A. , Kiley, M. P. , Holloway, B. P. , Auperin, D. D. (1993) Sequence analysis of the Ebola virus genome: organization, genetic elements, and comparison with the genome of Marburg virus. Virus Res. 29, 215–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Will, C. , Mühlberger, E. , Linder, D. , Slenczka, W. , Klenk, H. D. , Feldmann, H. (1993) Marburg virus gene 4 encodes the virion membrane protein, a type I transmembrane glycoprotein. J. Virol. 67, 1203–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Volchkov, V. E. , Volchkova, V. A. , Slenczka, W. , Klenk, H. D. , Feldmann, H. (1998) Release of viral glycoproteins during Ebola virus infection. Virology 245, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sanchez, A. , Trappier, S. G. , Mahy, B. W. , Peters, C. J. , Nichol, S. T. (1996) The virion glycoproteins of Ebola viruses are encoded in two reading frames and are expressed through transcriptional editing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 3602–3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Volchkov, V. E. , Becker, S. , Volchkova, V. A. , Ternovoj, V. A. , Kotov, A. N. , Netesov, S. V. , Klenk, H. D. (1995) GP mRNA of Ebola virus is edited by the Ebola virus polymerase and by T7 and vaccinia virus polymerases. Virology. 214, 421‐430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Feldmann, H. , Mühlberger, E. , Randolf, A. , Will, C. , Kiley, M. P. , Sanchez, A. , Klenk, H. D. (1992) Marburg virus, a filovirus: messenger RNAs, gene order, and regulatory elements of the replication cycle. Virus Res. 24, 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Noda, T. , Sagara, H. , Suzuki, E. , Takada, A. , Kida, H. , Kawaoka, Y. (2002) Ebola virus VP40 drives the formation of virus‐like filamentous particles along with GP. J. Virol. 76, 4855–4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dolnik, O. , Kolesnikova, L. , Becker, S. (2008) Filoviruses: Interactions with the host cell. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 756–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chan, S. Y. , Empig, C. J. , Welte, F. J. , Speck, R. F. , Schmaljohn, A. , Kreisberg, J. F. , Goldsmith, M. A. (2001) Folate receptor‐α is a cofactor for cellular entry by Marburg and Ebola viruses. Cell 106, 117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ito, H. , Watanabe, S. , Takada, A. , Kawaoka, Y. (2001) Ebola virus glycoprotein: proteolytic processing, acylation, cell tropism, and detection of neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 75, 1576–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Watanabe, S. , Takada, A. , Watanabe, T. , Ito, H. , Kida, H. , Kawaoka, Y. (2000) Functional importance of the coiled‐coil of the Ebola virus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 74, 10194–10201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weissenhorn, W. , Calder, L. J. , Wharton, S. A. , Skehel, J. J. , Wiley, D. C. (1998) The central structural feature of the membrane fusion protein subunit from the Ebola virus glycoprotein is a long triple‐stranded coiled coil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 6032–6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wool‐Lewis, R. J. , Bates, P. (1998) Characterization of Ebola virus entry by using pseudotyped viruses: identification of receptor‐deficient cell lines. J. Virol. 72, 3155–3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang, H. , Shi, Y. , Song, J. , Qi, J. , Lu, G. , Yan, J. , Gao, G. F. (2016) Ebola viral glycoprotein bound to its endosomal receptor Niemann‐Pick C1. Cell 164, 258–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sanchez, A. , Kiley, M. P. (1987) Identification and analysis of Ebola virus messenger RNA. Virology 157, 414–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ball, L. A. , Wertz, G. W. (1981) VSV RNA synthesis: how can you be positive? Cell 26, 143–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Weik, M. , Modrof, J. , Klenk, H. D. , Becker, S. , Mühlberger, E. (2002) Ebola virus VP30‐mediated transcription is regulated by RNA secondary structure formation. J. Virol. 76, 8532–8539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Klenk, H. D. , Feldmann, H. (2004) Ebola and Marburg Viruses: Molecular and Cellular Biology. Horizon Bioscience, Wymondham, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bray, M. , Davis, K. , Geisbert, T. , Schmaljohn, C. , Huggins, J. (1998) A mouse model for evaluation of prophylaxis and therapy of Ebola hemorrhagic fever. J. Infect. Dis. 178, 651–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bray, M. , Hatfill, S. , Hensley, L. , Huggins, J. W. (2001) Haematological, biochemical and coagulation changes in mice, guinea‐pigs and monkeys infected with a mouse‐adapted variant of Ebola Zaire virus. J. Comp. Pathol. 125, 243–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ebihara, H. , Takada, A. , Kobasa, D. , Jones, S. , Neumann, G. , Theriault, S. , Bray, M. , Feldmann, H. , Kawaoka, Y. (2006) Molecular determinants of Ebola virus virulence in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2, e73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Collaborative Cross Consortium . (2012) The genome architecture of the Collaborative Cross mouse genetic reference population. Genetics 190, 389–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rasmussen, A. L. , Okumura, A. , Ferris, M. T. , Green, R. , Feldmann, F. , Kelly, S. M. , Scott, D. P. , Safronetz, D. , Haddock, E. , LaCasse, R. , Thomas, M. J. , Sova, P. , Carter, V. S. , Weiss, J. M. , Miller, D. R. , Shaw, G. D. , Korth, M. J. , Heise, M. T. , Baric, R. S. , de Villena, F. P. , Feldmann, H. , Katze, M. G. (2014) Host genetic diversity enables Ebola hemorrhagic fever pathogenesis and resistance. Science 346, 987–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bird, B. H. , Spengler, J. R. , Chakrabarti, A. K. , Khristova, M. L. , Sealy, T. K. , Coleman‐McCray, J. D. , Martin, B. E. , Dodd, K. A. , Goldsmith, C. S. , Sanders, J. , Zaki, S. R. , Nichol, S. T. , Spiropoulou, C. F. (2016) Humanized mouse model of Ebola virus disease mimics the immune responses in human disease. J. Infect. Dis. 213, 703–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bente, D. , Gren, J. , Strong, J. E. , Feldmann, H. (2009) Disease modeling for Ebola and Marburg viruses. Dis. Model. Mech. 2, 12–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Geisbert, T. W. , Hensley, L. E. , Larsen, T. , Young, H. A. , Reed, D. S. , Geisbert, J. B. , Scott, D. P. , Kagan, E. , Jahrling, P. B. , Davis, K. J. (2003) Pathogenesis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever in cynomolgus macaques: evidence that dendritic cells are early and sustained targets of infection. Am. J. Pathol. 163, 2347–2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Geisbert, T. W. , Young, H. A. , Jahrling, P. B. , Davis, K. J. , Larsen, T. , Kagan, E. , Hensley, L. E. (2003) Pathogenesis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever in primate models: evidence that hemorrhage is not a direct effect of virus‐induced cytolysis of endothelial cells. Am. J. Pathol. 163, 2371–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Geisbert, T. W. , Hensley, L. E. , Gibb, T. R. , Steele, K. E. , Jaax, N. K. , Jahrling, P. B. (2000) Apoptosis induced in vitro and in vivo during infection by Ebola and Marburg viruses. Lab. Invest. 80, 171–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hensley, L. E. , Young, H. A. , Jahrling, P. B. , Geisbert, T. W. (2002) Proinflammatory response during Ebola virus infection of primate models: possible involvement of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily. Immunol. Lett. 80, 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ströher, U. , West, E. , Bugany, H. , Klenk, H. D. , Schnittler, H. J. , Feldmann, H. (2001) Infection and activation of monocytes by Marburg and Ebola viruses. J. Virol. 75, 11025–11033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gupta, M. , Mahanty, S. , Ahmed, R. , Rollin, P. E. (2001) Monocyte‐derived human macrophages and peripheral blood mononuclear cells infected with Ebola virus secrete MIP‐1α and TNF‐α and inhibit poly‐IC‐induced IFN‐α in vitro. Virology 284, 20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Baize, S. , Leroy, E. M. , Georges, A. J. , Georges‐Courbot, M. C. , Capron, M. , Bedjabaga, I. , Lansoud‐Soukate, J. , Mavoungou, E. (2002) Inflammatory responses in Ebola virus‐infected patients. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 128, 163–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ebihara, H. , Rockx, B. , Marzi, A. , Feldmann, F. , Haddock, E. , Brining, D. , LaCasse, R. A. , Gardner, D. , Feldmann, H. (2011) Host response dynamics following lethal infection of rhesus macaques with Zaire Ebolavirus. J. Infect. Dis. 204 (Suppl 3), S991–S999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sanchez, A. , Lukwiya, M. , Bausch, D. , Mahanty, S. , Sanchez, A. J. , Wagoner, K. D. , Rollin, P. E. (2004) Analysis of human peripheral blood samples from fatal and nonfatal cases of Ebola (Sudan) hemorrhagic fever: cellular responses, virus load, and nitric oxide levels. J. Virol. 78, 10370–10377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Villinger, F. , Rollin, P. E. , Brar, S. S. , Chikkala, N. F. , Winter, J. , Sundstrom, J. B. , Zaki, S. R. , Swanepoel, R. , Ansari, A. A. , Peters, C. J. (1999) Markedly elevated levels of interferon (IFN)‐γ, IFN‐α, interleukin (IL)‐2, IL‐10, and tumor necrosis factor‐α associated with fatal Ebola virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 179 (Suppl 1), S188–S191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wauquier, N. , Becquart, P. , Padilla, C. , Baize, S. , Leroy, E. M. (2010) Human fatal Zaire Ebola virus infection is associated with an aberrant innate immunity and with massive lymphocyte apoptosis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4, e837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gupta, M. , Mahanty, S. , Bray, M. , Ahmed, R. , Rollin, P. E. (2001) Passive transfer of antibodies protects immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice against lethal Ebola virus infection without complete inhibition of viral replication. J. Virol. 75, 4649–4654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Baize, S. , Leroy, E. M. , Mavoungou, E. , Fisher‐Hoch, S. P. (2000) Apoptosis in fatal Ebola infection: does the virus toll the bell for immune system? Apoptosis 5, 5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Geisbert, T. W. , Young, H. A. , Jahrling, P. B. , Davis, K. J. , Kagan, E. , Hensley, L. E. (2003) Mechanisms underlying coagulation abnormalities in Ebola hemorrhagic fever: overexpression of tissue factor in primate monocytes/macrophages is a key event. J. Infect. Dis. 188, 1618–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mahanty, S. , Hutchinson, K. , Agarwal, S. , McRae, M. , Rollin, P. E. , Pulendran, B. (2003) Cutting edge: impairment of dendritic cells and adaptive immunity by Ebola and Lassa viruses. J. Immunol. 170, 2797–2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bosio, C. M. , Aman, M. J. , Grogan, C. , Hogan, R. , Ruthel, G. , Negley, D. , Mohamadzadeh, M. , Bavari, S. , Schmaljohn, A. (2003) Ebola and Marburg viruses replicate in monocyte‐derived dendritic cells without inducing the production of cytokines and full maturation. J. Infect. Dis. 188, 1630–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lubaki, N. M. , Ilinykh, P. , Pietzsch, C. , Tigabu, B. , Freiberg, A. N. , Koup, R. A. , Bukreyev, A. (2013) The lack of maturation of Ebola virus‐infected dendritic cells results from the cooperative effect of at least two viral domains. J. Virol. 87, 7471–7485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cárdenas, W. B. , Loo, Y. M. , Gale, M., Jr. , Hartman, A. L. , Kimberlin, C. R. , Martínez‐Sobrido, L. , Saphire, E. O. , Basler, C. F. (2006) Ebola virus VP35 protein binds double‐stranded RNA and inhibits alpha/beta interferon production induced by RIG‐I signaling. J. Virol. 80, 5168–5178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Luthra, P. , Ramanan, P. , Mire, C. E. , Weisend, C. , Tsuda, Y. , Yen, B. , Liu, G. , Leung, D. W. , Geisbert, T. W. , Ebihara, H. , Amarasinghe, G. K. , Basler, C. F. (2013) Mutual antagonism between the Ebola virus VP35 protein and the RIG‐I activator PACT determines infection outcome. Cell Host Microbe 14, 74–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Basler, C. F. , Mikulasova, A. , Martinez‐Sobrido, L. , Paragas, J. , Mühlberger, E. , Bray, M. , Klenk, H. D. , Palese, P. , García‐Sastre, A. (2003) The Ebola virus VP35 protein inhibits activation of interferon regulatory factor 3. J. Virol. 77, 7945–7956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Prins, K. C. , Cárdenas, W. B. , Basler, C. F. (2009) Ebola virus protein VP35 impairs the function of interferon regulatory factor‐activating kinases IKK and TBK‐1. J. Virol. 83, 3069–3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Chang, T. H. , Kubota, T. , Matsuoka, M. , Jones, S. , Bradfute, S. B. , Bray, M. , Ozato, K. (2009) Ebola Zaire virus blocks type I interferon production by exploiting the host SUMO modification machinery. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Prins, K. C. , Delpeut, S. , Leung, D. W. , Reynard, O. , Volchkova, V. A. , Reid, S. P. , Ramanan, P. , Cárdenas, W. B. , Amarasinghe, G. K. , Volchkov, V. E. , Basler, C. F. (2010) Mutations abrogating VP35 interaction with double‐stranded RNA render Ebola virus avirulent in guinea pigs. J. Virol. 84, 3004–3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mateo, M. , Reid, S. P. , Leung, L. W. , Basler, C. F. , Volchkov, V. E. (2010) Ebolavirus VP24 binding to karyopherins is required for inhibition of interferon signaling. J. Virol. 84, 1169–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Reid, S. P. , Leung, L. W. , Hartman, A. L. , Martinez, O. , Shaw, M. L. , Carbonnelle, C. , Volchkov, V. E. , Nichol, S. T. , Basler, C. F. (2006) Ebola virus VP24 binds karyopherin α1 and blocks STAT1 nuclear accumulation. J. Virol. 80, 5156–5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Reid, S. P. , Valmas, C. , Martinez, O. , Sanchez, F. M. , Basler, C. F. (2007) Ebola virus VP24 proteins inhibit the interaction of NPI‐1 subfamily karyopherin α proteins with activated STAT1. J. Virol. 81, 13469–13477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Xu, W. , Edwards, M. R. , Borek, D. M. , Feagins, A. R. , Mittal, A. , Alinger, J. B. , Berry, K. N. , Yen, B. , Hamilton, J. , Brett, T. J. , Pappu, R. V. , Leung, D. W. , Basler, C. F. , Amarasinghe, G. K. (2014) Ebola virus VP24 targets a unique NLS binding site on karyopherin α5 to selectively compete with nuclear import of phosphorylated STAT1. Cell Host Microbe 16, 187–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Jaax, N. K. , Davis, K. J. , Geisbert, T. J. , Vogel, P. , Jaax, G. P. , Topper, M. , Jahrling, P. B. (1996) Lethal experimental infection of rhesus monkeys with Ebola‐Zaire (Mayinga) virus by the oral and conjunctival route of exposure. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 120, 140–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bradfute, S. B. , Braun, D. R. , Shamblin, J. D. , Geisbert, J. B. , Paragas, J. , Garrison, A. , Hensley, L. E. , Geisbert, T. W. (2007) Lymphocyte death in a mouse model of Ebola virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 196 (Suppl 2), S296–S304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Reed, D. S. , Hensley, L. E. , Geisbert, J. B. , Jahrling, P. B. , Geisbert, T. W. (2004) Depletion of peripheral blood T lymphocytes and NK cells during the course of Ebola hemorrhagic fever in cynomolgus macaques. Viral Immunol. 17, 390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gupta, M. , Spiropoulou, C. , Rollin, P. E. (2007) Ebola virus infection of human PBMCs causes massive death of macrophages, CD4 and CD8 T cell sub‐populations in vitro. Virology 364, 45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Baize, S. , Leroy, E. M. , Georges‐Courbot, M. C. , Capron, M. , Lansoud‐Soukate, J. , Debré, P. , Fisher‐Hoch, S. P. , McCormick, J. B. , Georges, A. J. (1999) Defective humoral responses and extensive intravascular apoptosis are associated with fatal outcome in Ebola virus‐infected patients. Nat. Med. 5, 423–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bradfute, S. B. , Swanson, P. E. , Smith, M. A. , Watanabe, E. , McDunn, J. E. , Hotchkiss, R. S. , Bavari, S. (2010) Mechanisms and consequences of Ebolavirus‐induced lymphocyte apoptosis. J. Immunol. 184, 327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rath, P. C. , Aggarwal, B. B. (1999) TNF‐induced signaling in apoptosis. J. Clin. Immunol. 19, 350–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Simon, H. U. , Haj‐Yehia, A. , Levi‐Schaffer, F. (2000) Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis 5, 415–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Snyder, C. M. , Shroff, E. H. , Liu, J. , Chandel, N. S. (2009) Nitric oxide induces cell death by regulating anti‐apoptotic BCL‐2 family members. PLoS One 4, e7059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]