Short abstract

Redirecting macrophage polarization with PGE2 inhibits development of allergic lung inflammation, and independent of macrophage origin, increasing its potential for therapy.

Keywords: hematopoietic, embryonic, targeting, asthma, alveolar

Abstract

In healthy lungs, many macrophages are characterized by IL‐10 production, and few are characterized by expression of IFN regulatory factor 5 (formerly M1) or YM1 and/or CD206 (formerly M2), whereas in asthma, this balance shifts toward few producing IL‐10 and many expressing IFN regulatory factor 5 or YM1/CD206. In this study, we tested whether redressing the balance by reinstating IL‐10 production could prevent house dust mite‐induced allergic lung inflammation. PGE2 was found to be the best inducer of IL‐10 in macrophages in vitro. Mice were then sensitized and challenged to house dust mites during a 2 wk protocol while treated with PGE2 in different ways. Lung inflammation was assessed 3 d after the last house dust mite challenge. House dust mite‐exposed mice treated with free PGE2 had fewer infiltrating eosinophils in lungs and lower YM1 serum levels than vehicle‐treated mice. Macrophage‐specific delivery of PGE2 did not affect lung inflammation. Adoptive transfer of PGE2‐treated macrophages led to fewer infiltrating eosinophils, macrophages, (activated) CD4+, and regulatory T lymphocytes in lungs. Our study shows that the redirection of macrophage polarization by using PGE2 inhibits development of allergic lung inflammation. This beneficial effect of macrophage repolarization is a novel avenue to explore for therapeutic purposes.

Abbreviations

- BM

bone marrow

- DC

dendritic cell

- EP

E prostanoid receptor

- HDM

house dust mite

- i.n.

intranasally

- IRF5

IFN regulatory factor 5

- i.t.

intratracheally

- M0

unstimulated macrophages

- Man‐HSA

mannosylated HSA

- MHC II

MHC class II

- MPGE2

PGE2‐treated macrophages

- PMH

PGE2 coupled to mannosylated HSA

- YM1

eosinophil chemotactic factor‐L

Introduction

Allergic asthma is a prevalent disease of the airways characterized by chronic inflammation of the airways with infiltration of eosinophils, Th2 lymphocytes, and the presence of alternatively activated macrophages [1, 2, 3, 4, 5–6]. The role of macrophages in the development and progression of asthma has been a hot topic of late. Alveolar macrophages were shown to be derived from embryonic progenitors, as opposed to circulating monocytes (and thus, hematopoietic stem cells), and were shown to self‐maintain during steady‐state conditions [7, 8–9]. This led to studies investigating the origin of macrophages during allergic inflammation that characterizes asthma [10, 11]. These studies indicate that immediately after allergen exposure, monocytes are recruited to the lung and may develop into alveolar macrophages. At later time points though, resident alveolar macrophages proliferate and constitute the main component of the alveolar macrophage pool. In addition, some recent and older studies have also highlighted the importance of resident alveolar macrophages in the maintaining homeostasis in lung tissue and immigrating monocyte‐derived macrophages in contributing to allergic inflammation [10, 11, 12–13]. The picture that arises is one of fast recruitment of monocytes after allergen exposure to fight the perceived dangers of the allergen with consequent inflammation and subsequent expansion of alveolar macrophages to restore homeostasis. In asthma, however, this homeostasis is not achieved.

For yet unknown reasons, the Th2‐type inflammation persists, giving rise to eosinophil infiltration and switching of macrophages to an alternatively activated phenotype by the high presence of cytokines, such as IL‐4 and IL‐13 [14]. Macrophages can be polarized into many different phenotypes that are hard to define in vivo [15, 16]. We have shown previously that many macrophages in healthy lungs are characterized by production of IL‐10, and few are characterized by expression of IRF5 (classically activated macrophages, formerly known as M1) or YM1 and/or CD206 (alternatively activated macrophages, formerly known as M2), whereas in asthma, this balance shifts toward few producing IL‐10 and many expressing IRF5 or YM1/CD206 [1, 4, 5, 17]. This finding suggested to us that it would perhaps be possible to reinstate homeostatic behavior of macrophages by inducing IL‐10 production in macrophages in vivo in lung tissue and thereby, treat allergic lung inflammation. To do this, we first investigated what stimulus could effectively induce IL‐10 production in macrophages, and this proved to be PGE2. We then continued with several ways of offering PGE2 to lung macrophages in mice to study its effect on the development of HDM‐induced allergic lung inflammation, i.e., i.n. treatment with free PGE2, i.n. treatment with PMH for macrophage‐specific uptake, and i.t.‐adoptive transfer of MPGE2. In addition, we studied whether inducing homeostatic behavior in hematopoietic stem cell‐derived macrophages differed from resident lung macrophages with respect to their effects on development of allergic lung inflammation to investigate if macrophage origin could influence their homeostatic behavior.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Female BALB/cOlaHsd mice (6–8 wk; Harlan, Horst, The Netherlands) and DO11.10 T cell TCR‐transgenic mice (Central Animal Facility, University of Groningen, The Netherlands) were housed in groups of 4 and had ad libitum access to water and food. Experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (University of Groningen) and performed under strict governmental and international guidelines.

RAW264.7 cultures to assess IL‐10 production

Murine RAW264.7 macrophages (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in DMEM (BE12‐604F; BioWhittaker, Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) at passages 5–15 (+pyruvate; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA), supplemented with 10% FCS (Invitrogen, Bleiswijk, The Netherlands), 4.5 g/l glucose, 2 mM l‐glutamine (Gibco, Life Technologies, Bleiswijk, The Netherlands), and 11 mg/l gentamicin (Gibco, Life Technologies). Details of induction and analysis of IL‐10 in RAW264.7 macrophages can be found in the supplemental data.

Effects of PGE2 and PMH in a model of asthma

Mice (n = 4/group) were exposed i.n. to whole‐body HDM extract (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus; Greer Laboratories, Lenoir, NC, USA), according to a model described previously [4]. In brief, mice received 100 μg HDM in 40 μl PBS i.n. on d 0 and were challenged with 10 μg HDM in 40 μl on d 7–11. Controls were exposed to 40 μl PBS (n = 8). On d 7, 9, and 11, mice were treated i.n. with 37 μl PMH (details on synthesis and characterization can be found in Supplemental Data) in 3 different concentrations (1.85, 3.70, and 7.40 mg/kg) or with free PGE2 in the same molar concentrations (0.10, 0.20, and 0.40 mg/kg). The control group received mannose‐HSA (details on synthesis and characterization can be found in Supplemental Data) in the same molar concentration as the highest PMH‐treated group (7.0 mg/kg mannose‐HSA). Additionally, 1 group was treated with PBS. Mice were euthanized on d 14. The left lung lobe was collected to isolate lung cells for flow cytometry, and the right lung was inflated with 0.5 ml 50% Tissue‐Tek optimum cutting temperature compound (Sakura, Finetek Europe B.V., Zoeterwoude, The Netherlands) in PBS and zinc‐fixed for histologic analyses (details can be found in the Supplemental Data).

Effects of adoptive transfer of lung and bone‐marrow MPGE2s in a model of asthma

Mice (n = 4/group) received 100 μg HDM i.n. in 40 μl PBS on d 0. On d 6, control mice received 50 μl PBS i.t., and HDM‐exposed mice received PBS, 0.15 106 unstimulated (M0), or 0.15 106 alveolar or bone marrow‐derived MPGE2s (details can be found in the Supplemental Data) in 50 μl PBS i.t. On d 7–11, mice received 10 μg HDM in 40 μl PBS. Healthy controls received PBS. Mice were euthanized on d 14, and lungs were collected as described above (details can be found in the Supplemental Data).

Effects of coculture of DCs and macrophages on DC function

Mature BM‐derived DCs were cocultured with M0 or MPGE2 for 24 h in DMEM (details can be found in the Supplemental Data). Macrophages were precultured for 48 h with 10 μM PGE2 or nothing and thoroughly washed with medium before addition of DCs. During coculture, 100 μl/ml OVA was added to prepare the DCs for coculture with T lymphocytes from DO11.10 T cell TCR‐transgenic mice to investigate their T lymphocyte‐stimulating properties (details can be found in the Supplemental Data). Control coculture wells did not receive OVA.

Statistics

Data are represented as means ± sem. If not normally distributed, data were log transformed. One‐way ANOVA, followed by Holm‐Sidak's multiple comparisons test, was used to test differences in the case of a normal distribution. In the case of non‐normal distribution after transformation, a Kruskal‐Wallis test, followed by a Dunn's multiple comparisons test, was used. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

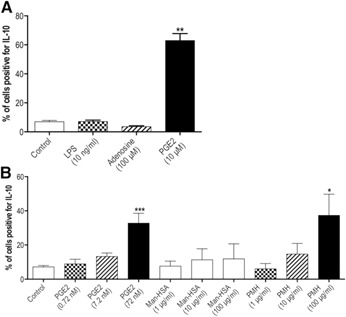

In this study, we boosted the anti‐inflammatory function of macrophages by stimulating IL‐10 expression. Our previous studies showed that IL‐10‐expressing macrophages disappear in lung tissue of human asthmatics and in mouse models of allergic and nonallergic lung inflammation, whereas macrophages associated with IL‐4/IL‐13 stimulation increase (refs. [1, 4, 17] and [unpublished results]). Therefore, we incubated RAW264.7 macrophages with a number of substances that have been reported to stimulate IL‐10 expression in macrophages, namely adenosine, PGE2, and LPS [18, 19, 20–21]. Of these three, PGE2 was the only one that could significantly stimulate IL‐10 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages, leading to a 5‐fold increase in the number of IL‐10‐positive macrophages ( Fig. 1A ). PGE2 is a well‐known, antiasthmatic compound that has been shown to prevent allergen‐induced bronchoconstriction and inhibit airway hyper‐responsiveness and inflammation [22]. These antiasthmatic effects were shown to be mediated through EP2 and EP4 on T lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages, mast cells, and bronchial smooth muscle cells [23, 24, 25, 26, 27–28]. This wide range of target cells, of course, presented us with a challenge in trying to show anti‐inflammatory effects of PGE2 on macrophages specifically. Therefore, we also studied a more macrophage‐specific preparation of PGE2, namely PMH. We have shown before that mannosylated albumin is taken up specifically by macrophages expressing the mannose receptor (CD206) [29]. As macrophages in asthmatic lungs are characterized by high expression of CD206 [1, 17], we coupled PMH for macrophage‐specific uptake and possibly macrophage‐specific effects. The treatment of macrophages with 100 μg/ml PMH induced similar high numbers of IL‐10‐expressing macrophages compared with an equimolar amount of free PGE2 (Fig. 1B). When lowering the dose of either PMH or free PGE2 tenfold or a hundredfold, we found a dose‐dependent reduction of the number of IL‐10‐expressing macrophages. Macrophages treated with mannosylated HSA in similar concentrations as PMH were not stimulated to express more IL‐10 as compared to untreated control macrophages.

Figure 1.

(A) The percentage of RAW 264.7 macrophages expressing IL‐10 is significantly higher after being stimulated with 10 μM PGE2 compared with nonstimulated controls (n = 8). Stimulation with 10 ng/ml LPS or 100 μM adenosine did not result in more macrophages expressing IL‐10 (n = 3). **P < 0.01 using a Kruskal‐Wallis test, followed by a Dunn's multiple comparisons test comparing the different treatment groups vs. control. (B) The percentage of RAW 264.7 macrophages expressing IL‐10 is significantly higher after being stimulated with increasing amounts PGE2 or with equimolar, increasing amounts of PMH compared with nonstimulated controls (n = 7). Equimolar amounts of Man‐HSA did not affect the number of IL‐10‐expressing macrophages (n = 7). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 using a Kruskal‐Wallis test, followed by a Dunn's multiple comparisons test comparing the different treatment groups vs. control.

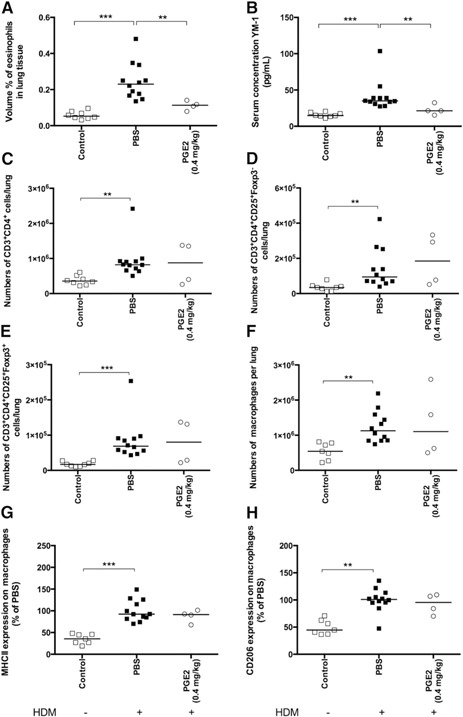

Having found that free PGE2 and PMH could stimulate IL‐10 expression in macrophages in vitro, we treated mice with three different concentrations of each compound during the induction of allergic lung inflammation to investigate whether they could dampen inflammation. Exposure to HDM induced significantly higher numbers of eosinophils, (activated) CD4+ T lymphocytes, regulatory T lymphocytes, and higher levels of YM1 in lung tissue compared with control mice ( Fig. 2A–E ). Treatment with free PGE2 led to a clear and dose‐dependent reduction of eosinophils and YM1 in lung tissue, with the highest dose being the most effective. The results presented in Fig. 2 show the effects of the highest PGE2 dose of 0.4 mg/kg; the results of the lower doses can be found in Supplemental Fig. 2A and B. There was no effect of this PGE2 dose on numbers of the different T lymphocyte subsets. HDM exposure also led to significantly more macrophages in lung tissue compared with control (Fig. 2F), and these HDM‐exposed macrophages expressed more CD206 and MHC II than macrophages from control lung tissue (Fig. 2G and H). Treatment with 0.4 mg/kg PGE2 did not affect numbers of lung macrophages or expressions of CD206 or MHC II on these macrophages.

Figure 2.

Mice exposed to HDM and treated with PBS during HDM exposure have significantly more infiltrating eosinophils in lung tissue (A), higher levels of YM1 in serum (B), more CD4+ T lymphocytes (C), more activated CD4+ T lymphocytes (D), more regulatory T lymphocytes (E), more macrophages (F), and higher expression of MHC II (G) and CD206 (H) on macrophages in lung tissue than healthy control mice. Treatment with 0.4 mg/kg PGE2 resulted in significantly lower eosinophil infiltration in lung tissue and lower levels of YM1 compared with PBS‐treated animals but had no effect on the infiltrating T lymphocyte subsets and the number of macrophages in lung tissue or the expression of MHC II and CD206 on these macrophages. Foxp3, Forkhead box p3. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 using a Kruskal‐Wallis test, followed by a Dunn's multiple comparisons test comparing control vs. PBS and PBS vs. PGE2.

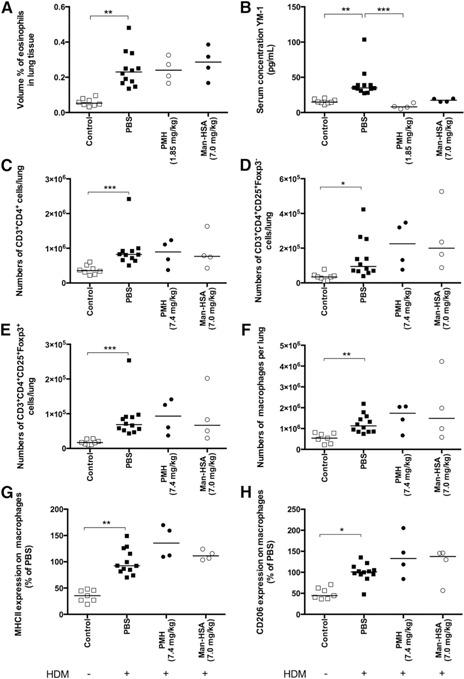

Thus, we could confirm that free PGE2 instilled in the lungs had anti‐inflammatory potential, as was shown in many studies before, but whether this was a result of a specific effect on macrophages was unclear. Our macrophage‐specific construct of PMH (7.4 mg/kg) induced IL‐10 expression significantly in macrophages in vitro but failed to have any anti‐inflammatory effects in vivo ( Fig. 3A–H ). There are several possible explanations for this phenomenon. The use of mannosylated albumin directs the construct toward uptake through mannose receptors [29], degradation of the construct in lysosomes, and potentially to the release of free PGE2. The receptors for PGE2 are, of course, on the outside of the cell, and the effectiveness of this approach relies on the PGE2 being released outside of the cell again. Our in vitro experiments showed that this does work, and PGE2 coupled to mannosylated albumin can be as effective as free PGE2. However, in vivo distribution and elimination effects may have impeded its effects. For instance, mature alveolar macrophages have a much higher expression of mannose receptors than interstitial or monocyte‐derived macrophages [30] and may have scavenged most of the construct as a result of their high receptor density and their prime location on the treatment side in the lungs (the construct was instilled i.n.). This is of relevance, as studies from Zaslona et al. [10] and Gundra et al. [31] have shown that mature alveolar macrophages protect against allergic lung inflammation, whereas newly derived macrophages from proliferation or recruited monocytes may be promoting development of inflammation. Therefore, the mannose receptor‐directed version of PGE2 may have been scavenged by the cells that do not need to be modified.

Figure 3.

Mice exposed to HDM and treated with PBS during HDM exposure have significantly more infiltrating eosinophils in lung tissue (A), higher levels of YM1 in serum (B), more CD4+ T lymphocytes (C), more activated CD4+ T lymphocytes (D), more regulatory T lymphocytes (E), more macrophages (F), and higher expression of MHC II (G) and CD206 (H) on macrophages in lung tissue than healthy control mice. Treatment with 7.4 mg/kg PMH (equimolar to 0.4 mg/kg PGE2) did not affect eosinophil, CD4+ T lymphocyte infiltration, number of macrophages in lung tissue, or the expression of MHC II and CD206 on these macrophages in lung tissue. Treatment with 7.4 mg/kg PMH did result in lower levels of YM1 in serum compared with PBS‐treated animals, but this was a result of an effect of treatment with empty carrier Man‐HSA, as treatment with an equimolar amount of 7.0 mg/kg Man‐HSA had the same effect. Treatment with Man‐HSA did not affect infiltration of eosinophils, T lymphocytes, number of macrophages in lung tissue, or the expression of MHC II and CD206 on these macrophages. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 using a Kruskal‐Wallis test, followed by a Dunn's multiple comparisons test comparing control vs. PBS, PBS vs. Man‐HSA, and Man‐HSA vs. PMH.

The only clear effect that the PGE2 construct had was a reduction in YM1 levels in serum. YM1 is highly produced by IL‐4/IL‐13‐stimulated macrophages in lung tissue, and we have found that levels in serum reflect lung tissue well in HDM‐induced lung inflammation (data not shown). As mannosylated albumin had the same effect with or without PGE2 being present, this appears to be the result of some interaction of the mannosylated construct with YM1 or the mannose receptor with YM1 production. To date, we have not been able to find any evidence to explain this observation.

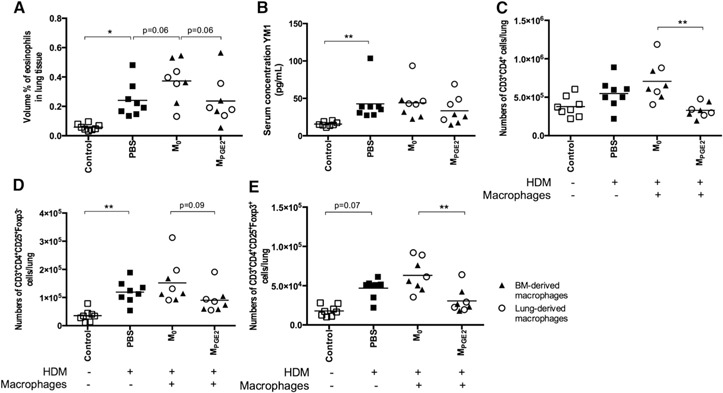

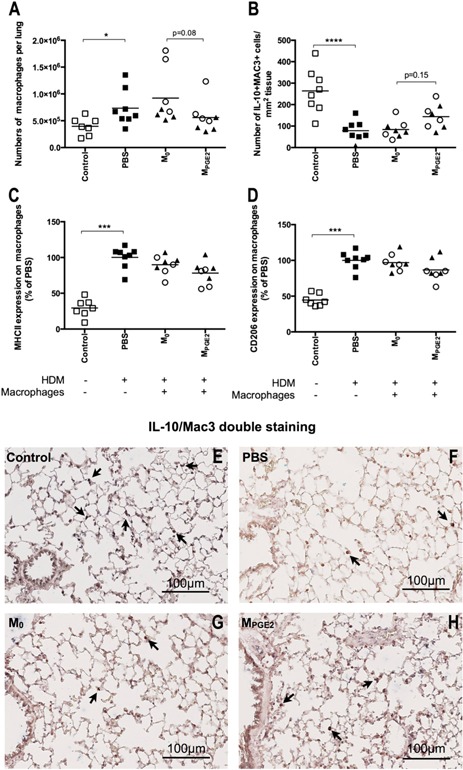

As our macrophage‐specific PGE2 formulation was not effective, we treated macrophages ex vivo with PGE2 to induce their anti‐inflammatory phenotype and adoptively transferred them into the lungs during the induction of allergic lung inflammation with HDM. This also gave us the opportunity to test whether macrophages with a hematopoietic origin would have a different effect compared with lung macrophages with an embryonic origin. We did not observe any differences between the effects of lung macrophages or BM‐derived macrophages, and therefore, we combined these groups in Fig. 4 . Adoptive transfer of untreated lung or BM‐derived macrophages (M0) had very little effect on development of allergic lung inflammation. There was a trend toward more eosinophils infiltrating lung tissue of HDM‐exposed mice that were treated with unstimulated macrophages compared with untreated HDM‐exposed mice (Fig. 4A; P = 0.06). Treatment with MPGE2s did affect development of HDM‐induced inflammation. Overall, less inflammation was seen with less infiltrating eosinophils (Fig. 4A; trend, P = 0.06) and less infiltrating CD4+ T lymphocytes (Fig. 4C), with both activated T lymphocytes and regulatory T lymphocytes being down (Fig. 4D and E) compared with treatment with unstimulated macrophages. In addition, we found a trend toward less macrophages being present ( Fig. 5A ; P = 0.08) and a trend toward higher numbers of IL‐10+ macrophages being present in lung tissue compared with treatment with unstimulated macrophages (Fig. 5B; P = 0.15). Other macrophage phenotypes (i.e., expression of MHC II or CD206; Fig. 5C and D) had not changed compared with treatment with unstimulated macrophages. Thus, this approach inhibited more HDM‐induced effects than treatment with free PGE2, and this may have been caused by the higher levels of PGE2 that the adoptively transferred macrophages were exposed to in vitro or the fact that multiple cell types in the lung are affected by free PGE2, which may have counterbalanced some of the macrophage‐specific effects. These findings indicate that the lower numbers of the IL‐10‐producing macrophages that we have found in asthma patients and in mouse models of asthma are important in the development of allergic inflammation, as reintroducing these macrophages into lung tissue has obvious beneficial effects [4, 17]. Whether these MPGE2s are also effective in asthma that already has fully developed is an important question that needs further studies. If so, this could open up a whole new therapeutic perspective for the treatment of asthma.

Figure 4.

Mice exposed to HDM and treated with PBS during HDM exposure have significantly more infiltrating eosinophils in lung tissue (A), higher levels of YM1 in serum (B), equal numbers of CD4+ T lymphocytes (C), more activated CD4+ T lymphocytes (D), and a trend toward more regulatory T lymphocytes (E) in lung tissue than healthy control mice. Adoptive transfer of M0 (open circles, lung macrophages; closed triangles, BM‐derived macrophages) did not affect these parameters, except for a trend toward more eosinophils in lung tissue compared with PBS‐treated animals. Adoptive transfer of MPGE2 resulted in a trend toward less eosinophil and effector T lymphocyte infiltration into lung tissue and significantly less CD4+ and regulatory T lymphocyte infiltration into lung tissue compared with mice that received unstimulated macrophages. There was no statistical difference between adoptively transferring lung macrophages or BM‐derived macrophages. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 using a Kruskal‐Wallis test, followed by a Dunn's multiple comparisons test comparing control vs. PBS, PBS vs. M0, and M0 vs. MPGE2.

Figure 5.

Mice exposed to HDM and treated with PBS during HDM exposure have significantly more total macrophages in lung tissue (A), less IL‐10+ macrophages (B), and higher expression of MHC II (C) and CD206 (D) on these macrophages than healthy control mice. Adoptive transfer of M0 (open circles, lung macrophages; closed triangles, BM‐derived macrophages) did not affect these parameters compared with PBS‐treated animals. Adoptive transfer of MPGE2 resulted in a trend toward less total macrophages and more IL‐10+ macrophages in lung tissue compared with mice that received unstimulated macrophages. Expressions of MHC II and CD206 were not affected by MPGE2s, and there was no statistical difference between adoptively transferring lung macrophages or BM‐derived macrophages. (E–H) Representative photos of the IL‐10/Mac3 double stainings are shown. Nuclear counter staining was omitted to maximize visibility of double‐positive cells (original magnification, 200×). Lung sections were stained for IL‐10 (blue) and a general macrophage marker Mac3 (red) to identify IL‐10+ macrophages specifically. The arrows indicate some examples of double‐positive cells, which were counted and related to total lung tissue surface, as depicted in B. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 using a Kruskal‐Wallis test, followed by a Dunn's multiple comparisons test comparing control vs. PBS, PBS vs. M0, and M0 vs. MPGE2.

An open question is the mechanism by which MPGE2s inhibit HDM‐induced lung inflammation. This could be a result of increased expression of IL‐10 by macrophages, as we found a trend toward more IL‐10‐expressing macrophages in lung tissue of the mice receiving MPGE2s. The groups of Holt and coworkers [13, 32, 33] described another possible mechanism many years ago. They showed that alveolar macrophages can down‐regulate the APC functions of DCs and directly inhibit T lymphocyte proliferation themselves. As we found that the inhibition of HDM‐induced lung inflammation by MPGE2s was most pronounced for the infiltration of CD4+ T lymphocytes, we subsequently investigated whether this effect was mediated through modulation of DC function by MPGE2s. To do this, we incubated M0 or MPGE2 with BM‐derived DCs, with or without OVA. After 24 h of coculture, the DCs were then cocultured with OVA‐specific CD4+ T lymphocytes to study effects on T lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production. DCs in the presence of OVA and unstimulated macrophages could effectively induce T lymphocyte proliferation with no particular direction in the response, as Th1‐, Th2‐, and Th17‐related cytokines were all produced more than when DCs were not preincubated with OVA and unstimulated macrophages ( Table 1 ). The preincubation of DCs with OVA and MPGE2s did not make any difference for T lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production compared with preincubation with unstimulated macrophages. Thus, we could not find evidence for this hypothesis. Therefore, it is likely that these anti‐inflammatory macrophages have a local effect through inhibiting T lymphocyte proliferation in lung tissue or through other anti‐inflammatory effects. The Peters‐Golden group [34] recently published an interesting suggestion with respect to this latter option. They showed that anti‐inflammatory effects of MPGE2s can be mediated through increased transcellular delivery of vesicular suppressor of cytokine signaling proteins. The elucidation of these pathways further may give valuable information on how to stimulate anti‐inflammatory behavior in macrophages without the help of PGE2. This is of particular interest, as the development of PGE2 as a drug in asthma has been hindered by its propensity to induce cough [35, 36].

Table 1.

BM‐derived DCs preincubated with M0 and cocultured with OVA‐specific CD4+ T lymphocytes induced significantly more T lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production when also exposed to OVA compared with no OVA being present. Preincubation of DC with MPGE2 did not affect this T lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production.

| T lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production a | DCs + T lymphocytes cocultured with no OVA, n = 6 | DCs (preincubated with M0) + T lymphocytes + OVA, n = 6 | DCs (preincubated with MPGE2) + T lymphocytes + OVA, n = 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| T lymphocyte proliferation | 20 ± 5 b | 100 ± 0 | 122 ± 67 |

| TNF‐α production | 5.2 ± 1.2 c | 100 ± 0 | 148 ± 28 |

| IFN‐γ production | 0.3 ± 0.2 c | 100 ± 0 | 107 ± 14 |

| IL‐6 production | 0.7 ± 0.4 c | 100 ± 0 | 197 ± 65 |

| IL‐12p70 production | 4.0 ± 2.4 c | 100 ± 0 | 112 ± 22 |

| IL‐4 production | 0.8 ± 0.3 d | 100 ± 0 | 81 ± 17 |

| IL‐5 production | 0.3 ± 0.2 d | 100 ± 0 | 74 ± 17 |

| IL‐13 production | 0.2 ± 0.1 d | 100 ± 0 | 95 ± 17 |

| IL‐10 production | 0 ± 0 c | 100 ± 0 | 119 ± 15 |

| IL‐17 production | 0.1 ± 0.03 c | 100 ± 0 | 103 ± 16 |

All are % of M0 + OVA.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01 all using a Kruskal‐Wallis test, followed by a Dunn's multiple comparisons test comparing no OVA vs. OVA + M0 and OVA + M0 vs. OVA + MPGE2.

In conclusion, our study has shown that redirecting macrophage polarization toward an anti‐inflammatory, IL‐10‐producing phenotype by using PGE2 inhibits the development of allergic lung inflammation. This beneficial effect of repolarization was independent of macrophage origin, increasing the potential of the approach for therapeutic purposes.

AUTHORSHIP

C.D. performed experiments and supervised pharmacy students, analyzed data, and wrote parts of the manuscript. C.E.B. assisted with animal experiments and data analysis and read and commented on the manuscript. C.R‐S. assisted with the synthesis of PMH and its analysis and read and commented on the manuscript. E.P. assisted with animal experiments and read and commented on the manuscript. K.P. assisted with data analysis and read and commented on the manuscript. B.N.M. designed the experimental studies, analyzed flow cytometry experiments, supervised pharmacy students, and wrote parts of the manuscript.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary data

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Grant 3.2.10.056 from The Netherlands Asthma Foundation (BNM). B.N.M. is an active member of COST action BM1201. The authors thank pharmacy students Marriël Schelhaas and Corine Habraken for their practical contributions to this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1. Melgert, B. N. , ten Hacken, N. H. , Rutgers, B. , Timens, W. , Postma, D. S. , Hylkema, M. N. (2011) More alternative activation of macrophages in lungs of asthmatic patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 127, 831–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bhakta, N. R. , Woodruff, P. G. (2011) Human asthma phenotypes: from the clinic, to cytokines, and back again. Immunol. Rev. 242, 220–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Melgert, B. N. , Oriss, T. B. , Qi, Z. , Dixon‐McCarthy, B. , Geerlings, M. , Hylkema, M. N. , Ray, A. (2010) Macrophages: regulators of sex differences in asthma? Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 42, 595–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Draijer C, Robbe P, Boorsma CE, Hylkema MN, Melgert, BN. (2013) Characterization of macrophage phenotypes in three murine models of house‐dust‐mite‐induced asthma. Mediators Inflamm. 2013, 632049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martinez, F. O. , Helming, L. , Milde, R. , Varin, A. , Melgert, B. N. , Draijer, C. , Thomas, B. , Fabbri, M. , Crawshaw, A. , Ho, L. P. , Ten Hacken, N. H. , Cobos Jiménez, V. , Kootstra, N. A. , Hamann, J. , Greaves, D. R. , Locati, M. , Mantovani, A. , Gordon, S. (2013) Genetic programs expressed in resting and IL‐4 alternatively activated mouse and human macrophages: similarities and differences. Blood 121, e57–e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Staples, K. J. , Hinks, T. S. C. , Ward, J. A. , Gunn, V. , Smith, C. , Djukanović, R. (2012) Phenotypic characterization of lung macrophages in asthmatic patients: overexpression of CCL17. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 130, 1404.e7–1412.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guilliams, M. , De Kleer, I. , Henri, S. , Post, S. , Vanhoutte, L. , De Prijck, S. , Deswarte, K. , Malissen, B. , Hammad, H. , Lambrecht, B. N. (2013) Alveolar macrophages develop from fetal monocytes that differentiate into long‐lived cells in the first week of life via GM‐CSF. J. Exp. Med. 210, 1977–1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yona, S. , Kim, K.‐W. , Wolf, Y. , Mildner, A. , Varol, D. , Breker, M. , Strauss‐Ayali, D. , Viukov, S. , Guilliams, M. , Misharin, A. , Hume, D. A. , Perlman, H. , Malissen, B. , Zelzer, E. , Jung, S. (2013) Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity 38, 79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hashimoto, D. , Chow, A. , Noizat, C. , Teo, P. , Beasley, M. B. , Leboeuf, M. , Becker, C. D. , See, P. , Price, J. , Lucas, D. , Greter, M. , Mortha, A. , Boyer, S. W. , Forsberg, E. C. , Tanaka, M. , van Rooijen, N. , García‐Sastre, A. , Stanley, E. R. , Ginhoux, F. , Frenette, P. S. , Merad, M. (2013) Tissue‐resident macrophages self‐maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity 38, 792–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zasłona, Z. , Przybranowski, S. , Wilke, C. , van Rooijen, N. , Teitz‐Tennenbaum, S. , Osterholzer, J. J. , Wilkinson, J. E. , Moore, B. B. , Peters‐Golden, M. (2014) Resident alveolar macrophages suppress, whereas recruited monocytes promote, allergic lung inflammation in murine models of asthma. J. Immunol. 193, 4245–4253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee, Y. G. , Jeong, J. J. , Nyenhuis, S. , Berdyshev, E. , Chung, S. , Ranjan, R. , Karpurapu, M. , Deng, J. , Qian, F. , Kelly, E. A. B. , Jarjour, N. N. , Ackerman, S. J. , Natarajan, V. , Christman, J. W. , Park, G. Y. (2015) Recruited alveolar macrophages, in response to airway epithelial‐derived monocyte chemoattractant protein 1/CCl2, regulate airway inflammation and remodeling in allergic asthma. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 52, 772–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Careau, E. , Bissonnette, E. Y. (2004) Adoptive transfer of alveolar macrophages abrogates bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 31, 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holt, P. G. , Oliver, J. , Bilyk, N. , McMenamin, C. , McMenamin, P. G. , Kraal, G. , Thepen, T. (1993) Downregulation of the antigen presenting cell function(s) of pulmonary dendritic cells in vivo by resident alveolar macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 177, 397–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gordon, S. , Martinez, F. O. (2010) Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity 32, 593–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murray, P. J. , Allen, J. E. , Biswas, S. K. , Fisher, E. A. , Gilroy, D. W. , Goerdt, S. , Gordon, S. , Hamilton, J. A. , Ivashkiv, L. B. , Lawrence, T. , Locati, M. , Mantovani, A. , Martinez, F. O. , Mege, J.‐L. , Mosser, D. M. , Natoli, G. , Saeij, J. P. , Schultze, J. L. , Shirey, K. A. , Sica, A. , Suttles, J. , Udalova, I. , van Ginderachter, J. A. , Vogel, S. N. , Wynn, T. A. (2014) Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity 41, 14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martinez, F. O. , Gordon, S. (2015) The evolution of our understanding of macrophages and translation of findings toward the clinic. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 11, 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Robbe, P. , Draijer, C. , Borg, T. R. , Luinge, M. , Timens, W. , Wouters, I. M. , Melgert, B. N. , Hylkema, M. N. (2015) Distinct macrophage phenotypes in allergic and nonallergic lung inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 308, L358–L367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Németh, Z. H. , Lutz, C. S. , Csóka, B. , Deitch, E. A. , Leibovich, S. J. , Gause, W. C. , Tone, M. , Pacher, P. , Vizi, E. S. , Haskó, G. (2005) Adenosine augments IL‐10 production by macrophages through an A2B receptor‐mediated posttranscriptional mechanism. J. Immunol. 175, 8260–8270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harizi, H. , Juzan, M. , Pitard, V. , Moreau, J.‐F. , Gualde, N. (2002) Cyclooxygenase‐2‐issued prostaglandin E(2) enhances the production of endogenous IL‐10, which down‐regulates dendritic cell functions. J. Immunol. 168, 2255–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. MacKenzie, K. F. , Clark, K. , Naqvi, S. , McGuire, V. A. , Nöehren, G. , Kristariyanto, Y. , van den Bosch, M. , Mudaliar, M. , McCarthy, P. C. , Pattison, M. J. , Pedrioli, P. G. A. , Barton, G. J. , Toth, R. , Prescott, A. , Arthur, J. S. C. (2013) PGE(2) induces macrophage IL‐10 production and a regulatory‐like phenotype via a protein kinase A‐SIK‐CRTC3 pathway. J. Immunol. 190, 565–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van den Bosch, M. W. M. , Palsson‐Mcdermott, E. , Johnson, D. S. , O'Neill, L. A. J. (2014) LPS induces the degradation of programmed cell death protein 4 (PDCD4) to release Twist2, activating c‐Maf transcription to promote interleukin‐10 production. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 22980–22990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chung, K. F. (2005) Evaluation of selective prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) receptor agonists as therapeutic agents for the treatment of asthma. Sci. STKE 2005, pe47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Birrell, M. A. , Maher, S. A. , Dekkak, B. , Jones, V. , Wong, S. , Brook, P. , Belvisi, M. G. (2015) Anti‐inflammatory effects of PGE2 in the lung: role of the EP4 receptor subtype. Thorax 70, 740–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Serra‐Pages, M. , Torres, R. , Plaza, J. , Herrerias, A. , Costa‐Farré, C. , Marco, A. , Jiménez, M. , Maurer, M. , Picado, C. , de Mora, F. (2015) Activation of the prostaglandin E2 receptor EP2 prevents house dust mite‐induced airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation by restraining mast cells’ activity. Clin. Exp. Allergy 45, 1590–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Serra‐Pages, M. , Olivera, A. , Torres, R. , Picado, C. , de Mora, F. , Rivera, J. (2012) E‐Prostanoid 2 receptors dampen mast cell degranulation via cAMP/PKA‐mediated suppression of IgE‐dependent signaling. J. Leukoc. Biol. 92, 1155–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Benyahia, C. , Gomez, I. , Kanyinda, L. , Boukais, K. , Danel, C. , Leséche, G. , Longrois, D. , Norel, X. (2012) PGE(2) receptor (EP(4)) agonists: potent dilators of human bronchi and future asthma therapy? Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 25, 115–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zasłona, Z. , Okunishi, K. , Bourdonnay, E. , Domingo‐Gonzalez, R. , Moore, B. B. , Lukacs, N. W. , Aronoff, D. M. , Peters‐Golden, M. (2014) Prostaglandin E2 suppresses allergic sensitization and lung inflammation by targeting the E prostanoid 2 receptor on T cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 133, 379–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Säfholm, J. , Manson, M. L. , Bood, J. , Delin, I. , Orre, A.‐C. , Bergman, P. , Al‐Ameri, M. , Dahlén, S.‐E. , Adner, M. (2015) Prostaglandin E2 inhibits mast cell‐dependent bronchoconstriction in human small airways through the E prostanoid subtype 2 receptor. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 136, 1232.e1–1239.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Melgert, B. N. , Olinga, P. , Van Der Laan, J. M. , Weert, B. , Cho, J. , Schuppan, D. , Groothuis, G. M. , Meijer, D. K. , Poelstra, K. (2001) Targeting dexamethasone to Kupffer cells: effects on liver inflammation and fibrosis in rats. Hepatology 34, 719–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ezekowitz, R. A. , Stahl, P. D. (1988) The structure and function of vertebrate mannose lectin‐like proteins. J. Cell Sci. Suppl. 9, 121–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gundra, U. M. , Girgis, N. M. , Ruckerl, D. , Jenkins, S. , Ward, L. N. , Kurtz, Z. D. , Wiens, K. E. , Tang, M. S. , Basu‐Roy, U. , Mansukhani, A. , Allen, J. E. , Loke, P. (2014) Alternatively activated macrophages derived from monocytes and tissue macrophages are phenotypically and functionally distinct. Blood 123, e110–e122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Upham, J. W. , Strickland, D. H. , Bilyk, N. , Robinson, B. W. , Holt, P. G. (1995) Alveolar macrophages from humans and rodents selectively inhibit T‐cell proliferation but permit T‐cell activation and cytokine secretion. Immunology 84, 142–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Upham, J. W. , Strickland, D. H. , Robinson, B. W. , Holt, P. G. (1997) Selective inhibition of T cell proliferation but not expression of effector function by human alveolar macrophages. Thorax 52, 786–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bourdonnay, E. , Zasłona, Z. , Penke, L. R. K. , Speth, J. M. , Schneider, D. J. , Przybranowski, S. , Swanson, J. A. , Mancuso, P. , Freeman, C. M. , Curtis, J. L. , Peters‐Golden, M. (2015) Transcellular delivery of vesicular SOCS proteins from macrophages to epithelial cells blunts inflammatory signaling. J. Exp. Med. 212, 729–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Coleridge, H. M. , Coleridge, J. C. , Ginzel, K. H. , Baker, D. G. , Banzett, R. B. , Morrison, M. A. (1976) Stimulation of ‘irritant’ receptors and afferent C‐fibres in the lungs by prostaglandins. Nature 264, 451–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maher, S. A. , Belvisi, M. G. (2010) Prostanoids and the cough reflex. Lung 188 (Suppl 1), S9–S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data