Short abstract

Recruited monocytes limit ALI by clearing parasite‐infected cells via a CD36‐mediated mechanism.

Keywords: alveolar macrophage, CCR2, Plasmodium berghei, phagocytosis, acute lung injury

Abstract

Pulmonary complications occur in a significant percentage of adults and children during the course of severe malaria. The cellular and molecular innate immune mechanisms that limit the extent of pulmonary inflammation and preserve lung function during severe Plasmodium infections remain unclear. In particular, the contributions to pulmonary complications by parasitized erythrocyte sequestration and subsequent clearance from the lung microvasculature by immune cells have not been clearly defined. We used the Plasmodium berghei ANKA‐C57BL/6 mouse model of severe malaria to investigate the mechanisms governing the nature and extent of malaria‐associated lung injury. We have demonstrated that sequestration of infected erythrocytes on postcapillary endothelial surfaces results in acute lung injury and the rapid recruitment of CCR2+CD11b+Ly6Chi monocytes from the circulation. These recruited cells remain in the lungs as monocyte‐derived macrophages and are instrumental in the phagocytic clearance of adherent Plasmodium berghei‐infected erythrocytes. In contrast, alveolar macrophages do not play a significant role in the clearance of malaria‐infected cells. Furthermore, the results obtained from Ccr2−/−, Cd36−/−, and CD36 bone marrow chimeric mice showed that sequestration in the absence of CD36‐mediated phagocytic clearance by monocytes leads to exaggerated lung pathologic features. In summary, our data indicate that the intensity of malaria‐induced lung pathologic features is proportional to the steady‐state levels of Plasmodium‐infected erythrocytes adhering to the pulmonary vasculature. Moreover, the present work has defined a major role of recruited monocytes in clearing infected erythrocytes from the pulmonary interstitium, thus minimizing lung damage.

Abbreviations

- AMs

alveolar macrophages

- ALI

acute lung injury

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- DFCO

diffusion factor for carbon monoxide

- MDMs

monocyte‐derived macrophages

- MHCII

major histocompatibility II

- tdTPbA

Plasmodium berghei ANKA transgenic for tdTomato

- WT

wild type

Introduction

Malaria infects >200 million people annually, resulting in >600,000 deaths, mainly of children in Sub‐Saharan Africa [1]. Of the 5 species that infect humans, Plasmodium falciparum is responsible for most of the 68 million disability‐adjusted life years attributed to malaria [2]. Although Plasmodium infection of erythrocytes commonly results in cyclical fevers and anemia, some of the most serious complications are at the organ level in the brain, placenta, and lungs [3, 4–5]. Pulmonary complications occur in ≤25% of adults and 40% of children during the course of severe malaria [6, 7, 8–9]. In addition, 5–25% of adults and ≤30% of pregnant women have been reported to develop ALI or acute respiratory distress syndrome after administration of antimalarial drugs [8]. Traditionally, this malaria‐associated respiratory distress has been attributed to the combined effects of metabolic acidosis, noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, and severe anemia [10]. However, our understanding of the contributions to pulmonary injury made by the intense sequestration of malaria‐infected erythrocytes in the lung microvasculature remains limited.

Plasmodium sequestration in tissues is thought to be developmentally advantageous to the parasite, because it prevents the recognition and clearance of parasite‐containing erythrocytes by macrophages in the spleen [11]. Although the pathophysiological consequences of parasite sequestration on vascular endothelial cells in the brain and placenta are well documented, little is known about this process in the lungs. Because studying P. falciparum sequestration in intact human lungs is inherently difficult, murine models have been developed, most of which use P. berghei infection [12, 13, 14, 15, 16–17]. Similar to P. falciparum, P. berghei schizont‐containing erythrocytes sequester in the lungs and adipose tissue via interactions with CD36 [12, 16, 18]. Using the P. berghei model, it has been demonstrated that sequestration in the lungs, in addition to avoiding clearance in the spleen, has the added benefit of promoting parasite growth [13, 19]. From the perspective of the host, the adherence of parasitized erythrocytes to the pulmonary vasculature is not a benign event, because a strong positive correlation has been found between the level of parasite burden in the lungs and the degree of ALI [16]. Although some malaria‐associated pulmonary damage results directly when infected cells cytoadhere to the vascular endothelium [20], the contributions that immune responses make to malaria‐associated ALI remain unclear.

Malaria induces a robust innate immune response that plays an important role in limiting the parasite load through mechanisms that direct phagocytic cells to engulf and kill parasites and initiate the development of an appropriate T cell–mediated effector response [21]. Mononuclear phagocytes have been shown to be critical for the uptake and clearance of malaria‐infected erythrocytes [22]. Although the CD11b+Ly6Chi subset of inflammatory monocytes are central to the clearance of infected erythrocytes in the spleen, resulting in partial control of blood parasitemia [23], the role that blood monocytes and tissue‐resident macrophages play in regulation of the parasite burden in the lungs and malaria‐induced pulmonary damage have remained undefined.

In the present study, we have detailed the dynamics, activation status, and clearance function of recruited monocytes and tissue‐resident AMs in the lungs during the initial stages of P. berghei infection in C57BL/6 mice. We show that, coincident with the onset of parasite sequestration in the lungs, a rapid recruitment occurs of CD11b+Ly6Chi monocytes, which remain in the tissue as macrophages and are instrumental in controlling the level of pulmonary damage through phagocytic clearance of malaria‐infected erythrocytes adherent to lung endothelium. The lung‐resident AMs remain quiescent and do not directly participate in removal of the adherent cells from the lungs. Using Ccr2−/−, Cd36−/−, and CD36 bone marrow chimeric mice, we have demonstrated that impeding monocyte recruitment or blocking CD36‐mediated phagocytic clearance results in exaggerated lung pathologic features. Our data show that effective parasite clearance and control of P. berghei‐induced acute lung injury by recruited inflammatory monocytes is largely dependent on the expression of CD36 on the surface of mononuclear cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement

The Johns Hopkins University animal care and use committee approved all animal experiments (approval nos. MO10H29 and MO12H473) according to the standards set by the National Research Council's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Mice and parasites

Male (6–12‐wk‐old) mice were used for all experiments. C57BL/6J and Ccr2−/− (B6.129S4‐Ccr2tm1Ifc/J)] [24] mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Cd36−/− mice were obtained from Dr. Maria Febbraio (Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH, USA) [25]. The Ccr2−/− and Cd36−/− mice were backcrossed to C57BL/6J for 9 and 10 generations, respectively. The mice were maintained within ventilated cages receiving filtered air, provided food and water ad libitum, and exposed to a 12‐h light/dark cycle.

P. berghei ANKA (MRA‐671) was obtained from the Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center (Manassas, VA, USA). tdTPbA, which constitutively express tdTomato under control of the elongation factor 1α promoter, was obtained from Dr. Volker Heussler (Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, Hamburg, Germany) [26]. Cryopreserved parasite stocks were passaged through donor mice and used between passages 3 and 8. Infections were initiated by intraperitoneal inoculation of 106 parasitized erythrocytes. Sporozoite‐initiated infections were performed by intravenous injection of 1000 freshly isolated P. berghei sporozoites, as previously reported [27]. Parasitemia was monitored daily by collecting 1 drop of blood from the tail vein, making thin blood smears, and counting 4 microscopic fields containing ≥100 methanol‐fixed, Giemsa‐stained RBCs for each mouse.

Lung cell isolation

In brief, before excision from the chest cavity, the lungs were perfused with 10 ml of room temperature sterile Dulbecco's PBS via the right ventricle of the heart. The lungs were carefully removed and placed in 5 ml of RPMI 1640 containing 1 mg/ml collagenase type II (1701‐015; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 30 μg/ml DNase I (10104159001; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA), minced thoroughly, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Minced lung suspensions were then ground through a 100‐μm nylon cell strainer (no. 352360; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The resulting cells were pelleted at 1500 g at 4°C. The cells were suspended in ammonium‐chloride‐potassium lysing buffer (no. 118‐156‐721; Quality Biologic, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) to remove any contaminating erythrocytes, passed through a second cell strainer, and washed in FACS staining buffer (PBS containing 2% heat‐inactivated FCS; no. 35‐011‐CV; Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA).

Flow cytometry

The following antibodies were from BD Biosciences: CD11b‐PerCP‐Cy5.5 (no. 550993), SiglecF‐PE (no. 552126), Ly6C‐APC (no. 560595), CD64‐PE (no. 558455), and CD86‐PE (no. 553692). F4/80‐PE (no. 12‐4801‐80), MHCII‐PE (no. 12‐5321‐81), CD40‐PE (no. 12‐0401‐81), CD45.2‐PE (no. 12‐0454‐81), CD45.1‐APC (no. 912‐0453‐81), CD80‐PE (no. 12‐0801‐81), PD‐L1‐PE (no. 12‐5982‐81), PD‐L2‐PE (no. 12‐5986‐83), and rat IgG2aκ isotype control‐PE (no. 12‐4321‐80) anti‐mouse antibodies were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti‐CD11c‐APC (no. 130‐091‐844) was from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA, USA), and anti‐CD36 was from Cascade Biosciences (Winchester, MA, USA).

Cells were treated with CD16/CD32 Fc Block (BD Biosciences) 10 min before the addition of specific antibodies. Data were collected using a FACSCalibur (San Jose, CA, USA), and the data were analyzed using FlowJo (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA). An Amnis ImageStreamX Mark II cytometer (Amnis Corporation, Seattle, WA, USA) was used to capture images of the phagocytosis of tdTPbA. FlowSight software (Amnis) was used to identify and differentiate those cells that had internalized the infected erythrocytes from those that had infected erythrocytes bound to the surface.

BAL fluid

BAL was performed as previously described [28]. In brief, BAL fluid was obtained via tracheostomy and lavage with 800 μl (×3) of PBS. The BAL fluid was pooled, and 105 cells were adhered to microscope slides with the aid of cytology funnels (Fisher Scientific, Houston, TX, USA) and a cytocentrifuge (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) before methanol fixation and staining with Giemsa. The total protein and IgM concentrations in the recovered BAL fluid were determined using the Pierce BCA assay kit (Thermo Fisher) and the Bethyl mouse IgM ELISA kit (Bethyl Laboratories, Montogmery, TX, USA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Histologic examination

A 19‐gauge gavage tube was inserted into the trachea, and the lungs were inflated with zinc‐buffered formalin (Anatech Ltd., Battle Creek, MI, USA) at 30 cm H2O. The lungs were removed, incubated in zinc‐buffered formalin for 48 h, and embedded in paraffin, and 5‐μm sections were cut from 4 levels of the lung. The sections were stained with H&E, Prussian blue, or Mallory's phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin.

Bone marrow chimeras

Bone marrow cells were extracted from the femurs and tibias of CD45.1+ C57BL/6 (WT) and CD45.2+CD36−/− mice. After removal of erythrocytes using ammonium‐chloride‐potassium lysis buffer (Quality Biologic), bone marrow cells were suspended in PBS. Cohorts of WT and CD36−/− mice were irradiated with 900 rad using a [137Cs] γ‐source (Gammacell 40 Exactor; MSD Nordion, Laval, Quebec, Canada) and reconstituted 2 h later with 1 × 107 heterologous or autologous bone marrow cells introduced via the tail vein in 150 μl of PBS. The mice were maintained on sulfatrim (Actavis, Morristown, NJ, USA)‐supplemented water for 4 wk and allowed to recover for 9 wk before malaria infection. At 4 and 8 weeks after irradiation, the effectiveness of chimerism was evaluated by assessing the levels of CD45.1, CD45.2, and CD36 on CD11b+ cells. After applying Fc Block (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), the cells were incubated with the appropriate fluorochrome‐conjugated antibodies in FACS‐staining buffer for 20 min on ice in the dark. Data were acquired using a FACSCalibur and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA, USA), and the results were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Gene expression analysis

The lungs were homogenized in Trizol (Life Technologies), and isolated mRNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed with SuperScript II (Life Technologies) using oligo (dT) (12–18) primers. Quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR was performed using Assays‐On‐Demand and Universal Master Mix (Life Technologies). The following assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) were used: Ccl2 (Mm00441242_m1), Ccl3 (Mm00441259_g1), Ccl4 (Mm00443111_m1), Ccl7 (Mm00443113_m1), Ccl8 (Mm01297183_m1), Cx3cl1 (Mm00436454_m1), Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1), Ifng (Mm00801778_m1), Nos2 (Mm00440502_m1), and Tnf (Mm00443260_g1). The expression levels were normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Calculation of P. berghei genome equivalents was performed as described previously [29].

Measures of pulmonary edema

Pulmonary edema was assessed using gravimetric analysis. The lungs were removed after exsanguination, weighed wet, dried completely in a 65°C oven (>72 h), and weighed dry to determine the wet:dry ratio.

Evan's Blue (100 μl of a 1% solution) was administered intravenously and allowed to circulate for 1 h. The lungs were excised, weighed, homogenized in formamide, incubated at 60°C for 24 h, and centrifuged, and the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 620 nm and 740 nm. The corrected absorbance values were calculated as described previously [30].

Hemozoin

Hemozoin was purified as previously described [31]. In brief, the frozen lungs were homogenized and centrifuged, and the supernatant fraction was suspended in 2% SDS and 100 mM sodium bicarbonate. Washed pellets of hemozoin were suspended in 1 mg/ml proteinase K and incubated overnight at 60°C. Hemozoin was decrystallized in 2% SDS and 20 mM NaOH for 1 h and quantitated by OD at 400 nm.

Lung injury scores

H&E‐stained histologic sections from the test and control groups were evaluated in a blinded fashion by 3 of us. The number of hemozoin‐containing cells in a ×400 microscopic field was quantified from 10 fields per mouse, and a lung injury score was determined using 3 categories of histologic change: intra‐alveolar hemorrhage and infiltrates, alveolar septal thickening, and intra‐alveolar edema. Each of these categories was scored using a 4‐point system: 0 = no injury; 1 = <10% of the tissue section involved; 2 = 10–30% of the tissue section involved; 3 = 30–50% of the tissue section involved; and 4 = >50% of the tissue section involved.

Lung diffusing capacity and hematocrit determination

Changes to the lung diffusing capacity after malaria infection were assessed by determining the DFCO using a method we have previously described [32]. In brief, 800 μl of a mixture containing 0.5% Ne as an insoluble tracer gas, and 0.5% CO as a soluble tracer gas was introduced into the lungs via an 18‐gauge blunted needle for a 9‐s breath hold. Gas withdrawn from the lungs was then analyzed for Ne and CO compared with the control mixture using a desktop gas chromatograph, with DFCO defined as 1 − (CO9s/COc)/(Ne9s/Nec), where 9s is 9 s and c, the control. Although this method allows for a sensitive assessment of pulmonary function as it relates to structural changes within the alveolar tissue, it is also partly a function of the alveolar capillary blood volume and the rate of CO–hemoglobin binding—parameters that could be influenced by severe malarial anemia. As such, the DFCO values were interpreted with the hematocrit measurements at the time of sacrifice, obtained by drawing blood into heparinized microhematocrit tubes, spinning for 5 min in a hematocrit microfuge, and comparing the length of the packed cell volume relative to the total length of the blood sample.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was evaluated using the 2‐tailed Student t test to compare 2 groups or 1‐way analysis of variance test, coupled with Tukey's post hoc test, to compare multiple groups using Prism software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA).

RESULTS

P. berghei infection and ALI

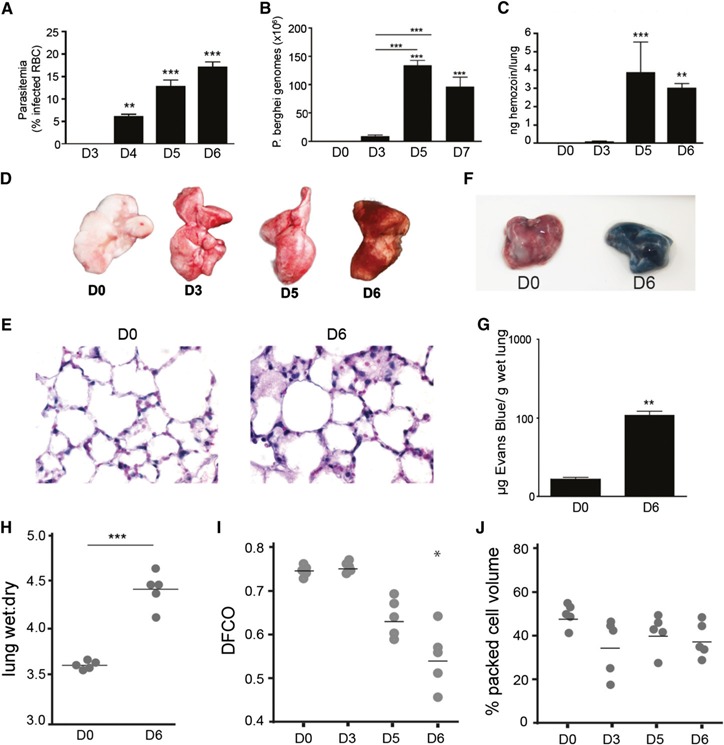

Given that C57BL/6 mice succumb to the effects of experimental cerebral malaria at 7 d after P. berghei infection, we assessed the effect of malaria on pulmonary inflammation over a 6‐d time course in this model system. As early as d 3 after P. berghei ANKA infection, when parasitemia ( Fig. 1A ) and sequestration in the lungs (Fig. 1B and C) were barely detectable, the mice showed evidence of organ‐level pathologic findings with lungs that appeared inflamed (Fig. 1D). As the infection progressed and the number of parasites associated with the lungs increased (peaking at ∼1.25 × 108 genomes at d 5; Fig. 1B), the outward appearance of the perfused lungs transitioned to a dark, reddish‐brown by d 6 (Fig. 1D). Although parasitemia continued to increase in the peripheral blood (Fig. 1A), the total parasitic burden detected in the perfused lungs after d 5 had plateaued or decreased (Fig. 1B and C).

Figure 1.

P. berghei infection leads to ALI. (A) Peripheral blood parasitemia of P. berghei ANKA‐infected C57BL/6 mice at d 3 (D3), 4 (D4), 5 (D5), and 6 (D6) of infection. Dynamics of parasite burden in perfused lungs of infected mice at various times after infection using PCR‐based detection of the P. berghei 18S rRNA gene (B) or spectrophotometric quantification of lung‐associated hemozoin (C). (D) Gross appearance of perfused lungs from C57BL/6 mice at D0, D3, D5, and D6 after P. berghei infection. (E) Representative histologic sections of lungs from noninfected mice on D0 or D6 after infection; 5‐µm sections were stained with H&E (magnification ×60). Gross appearance (F) and spectrophotometric quantitation of Evans blue extravasation (G) in lungs from D0 or D6. (H) Wet:dry ratios of lungs isolated from D0 or D6 mice. DFCO (I) and hematocrit (J) measured at designated times after infection. Bar graphs depict mean ± sem; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All comparisons were versus uninfected controls (n = 5).

In accordance with their gross appearance, the histologic analysis revealed evidence of tissue injury, manifesting as pulmonary edema, alveolar septal wall thickening, and mononuclear cell infiltration (Fig. 1E). P. berghei ANKA infection was accompanied by a change in vascular endothelial barrier function, denoted by a 30‐fold increase in the amount of extravasated Evan's blue in the lungs at d 6 after infection (Fig. 1F and G) and a significant elevation in the lung wet:dry ratio (Fig. 1H). In further assessing pulmonary inflammation within the airspaces, P. berghei infection resulted in elevated total protein and IgM levels recovered via BAL (Supplemental Fig. 1A and B). P. berghei ANKA infection was also accompanied by a significant increase in the number of cells in the BAL fluid at d 6 after infection, which were dominated by mononuclear cells displaying macrophage‐like morphology (<1% granulocytes and lymphocytes; Supplemental Fig. 1C and D). Most of the mononuclear cells in the BAL fluid had an activated appearance, with highly vacuolated cytoplasm and occasional evidence of recently engulfed parasitized RBCs (Supplemental Fig. 1D).

To address the possibility that the method used to initiate infection had an effect on the course and nature of the response in the lungs, we also performed sporozoite‐based infections. At d 8, when the parasitemia was comparable to that on d 5 of blood stage‐initiated infections, the mice infected via sporozoites had similar increases in lung parasite burdens and protein levels in the BAL fluid (Supplemental Fig. 1E–G). These findings suggest that both blood stage‐ and sporozoite‐initiated infections result in significant pulmonary parasite sequestration and lung injury.

In addition to the tissue damage we observed in the lungs, malaria infection had a detrimental effect on pulmonary function, as measured by a significant and progressive decrease in the diffusing capacity (DFCO) of the lungs (Fig. 1I). Importantly, the continual reduction in DFCO over the course of the infection was not directly proportional to changes in hematocrit (Fig. 1J), which remained relatively constant between d 3 and 6 after infection. This finding suggests that the reduction in DFCO is largely a consequence of either a loss of functional alveolar surface area due to edema in the alveolar spaces or increased alveolar septal thickening rather than malaria‐induced anemia.

Collectively, these measurements demonstrate that pulmonary malaria infection in this model meets all 4 of the features that define acute lung injury in experimental animal models: histologic evidence of tissue injury, alteration of the alveolar capillary barrier, the presence of an inflammatory response, and evidence of physiologic dysfunction [33].

Dynamics of AMs and recruited monocytes

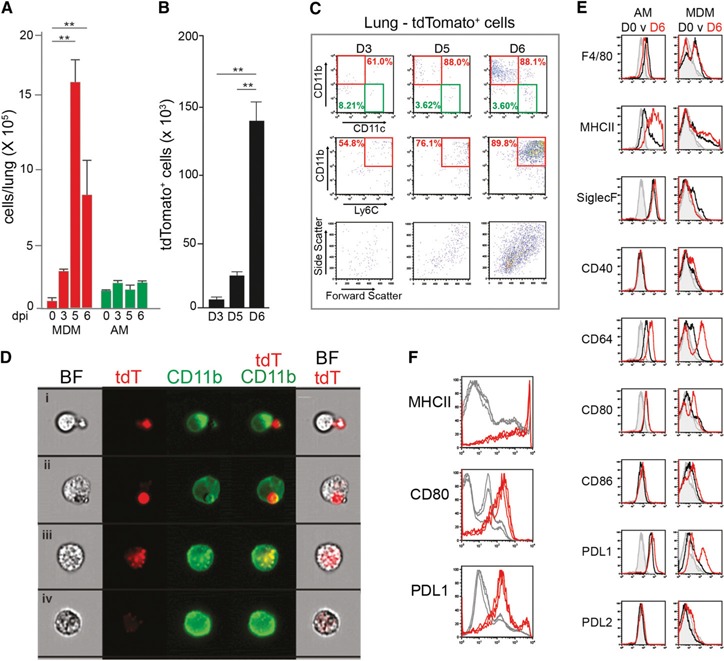

To determine whether the observed increase in mononuclear cells in the BAL fluid could be extended to the whole lung, flow cytometry was used to determine the population dynamics of monocytes and macrophages at d 3, 5, and 6 after P. berghei infection. Although the number of AMs (CD11c+SiglecF+CD64+CD11b−Ly6Clo) remained stable, a substantial increase was seen in the number of cells with the surface signature of inflammatory monocytes (CD11c−SiglecF−CD64+CD11b+Ly6Chi) seen as early as d 3 after infection ( Fig. 2A ). Because these CD11c−SiglecF−CD64+CD11b+Ly6Chi cells remained in the lung after perfusion (and, thus, were no longer in the vascular compartment), they were designated MDMs. Notably, sporozoite‐initiated infections also elicited the recruitment of MDMs to the lungs of P. berghei‐infected mice (Supplemental Fig. 1H).

Figure 2.

Dynamics of mononuclear cells and parasite phagocytosis in the lungs during P. berghei infection. (A) Change in the numbers of CD64+CD11b+CD11c− MDMs and CD64+CD11b−CD11c+ AMs. The numbers were derived from flow cytometric analysis of whole perfused lungs obtained at d 3 (D3), 5 (D5), and 6 (D6) after P. berghei ANKA infection (dpi). (B) Dynamics of cell‐associated tdTomato‐expressing P. berghei at D3, D5, and D6 of infection. Comparisons in bar graphs were versus noninfected controls. Data for (A) and (B) are mean ± sem; **P < 0.01 (n = 5). (C) Representative flow cytometry data depicting the dynamics of uptake of tdTPbA‐infected erythrocytes by CD11b+CD11c−Ly6Chi MDMs and CD11b−CD11c+Ly6Clo AMs from perfused lungs at D3, D5, and D6 after infection. Dot plots in the bottom row depict the light scatter properties of the tdTomato‐positive cells present in each population. (D) Representative bright field (BF), fluorescent, and merged images of the interactions between tdTPbA‐infected erythrocytes (tdT) and MDMs at D6 of infection. (E) Representative data (n = 3) of flow cytometric analyses of gated AMs and MDMs from the perfused lungs of mice at D0 or D6 after P. berghei ANKA infection. Histograms depict surface fluorescence signals of F4/80, MHCII, SiglecF, CD40, CD80, CD86, PDL1, PDL2, and CD64 (D0, black; D6, red) and their respective isotype controls (gray). (F) MDMs with elevated expression of the activation markers MHCII, CD80, and PDL1 at D6 of infection are associated with tdTPbA signal. Lung cells were first gated according to tdTomato fluorescence‐positive (red) and ‐negative (gray) cells and then analyzed for MHCII, CD80, and PDL1 levels. Data are representative of ≥3 independent repetitions.

The recruitment of MDMs into the lungs paralleled the changes in the transcription of the genes encoding CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL7, and CCL8 (Supplemental Fig. 1I)—chemokines known to promote the recruitment of mononuclear cells to sites of inflammation [34].

Recruited MDMs clear sequestered parasites

The significant increase of MDMs and the lack of a change in the number of AMs in the face of increasing parasitic load suggested that these 2 mononuclear cell populations could have distinct functional roles during malaria infection. To explore this issue, we used a transgenic P. berghei ANKA line that constitutively expresses the red fluorescent protein tdTomato (tdTPbA) to identify key phagocytic cells and assess the dynamics of parasite clearance [26]. Peripheral blood parasitemia monitored via tdTomato fluorescence confirmed that the dynamics of infection using the transgenic parasite was similar to that of the nonfluorescent P. berghei ANKA parent strain (Supplemental Fig. 1J). Using tdTomato fluorescence as a measure of parasite uptake, an overall increase occurred in the number of parasite‐positive cells from d 3 to 6 of infection (Fig. 2B). Evaluation of the surface phenotype of the tdTomato‐positive cells revealed that only a small percentage of the fluorescence was associated with AMs (8.2%, 3.6%, and 3.6% on d 3, 5, and 6, respectively). In contrast, a vast majority of the tdTPbA fluorescent signal was associated with MDMs (61%, 88%, and 88% on d 3, 5, and 6, respectively; Fig. 2C). Using flow cytometry‐assisted fluorescence microscopy, it was determined that the nature of the interactions between the MDMs and the tdTPbA‐infected erythrocytes included surface attachment, engulfment of intact infected erythrocytes, and intracellular degradation of the parasite (Fig. 2D).

Activation status of AMs and MDMs

To determine whether the distinctions in the dynamics and phagocytic function of AMs and MDMs were reflected by their activation status, the expression levels of F4/80, MHCII, SiglecF, CD40, CD64, CD80, CD86, PDL1, and PDL2 were compared. The AMs from naïve mice were F4/80low, MHCIIlow/mid, SiglecF+, and CD64+ (Fig. 2E, left column [black]) [35, 36]. The AMs were also PDL1+ and expressed low levels of CD80. With the exception of a substantial increase in the expression of MHCII, the d 6 AMs had a nearly identical surface phenotype as the cells from naïve mice (Fig. 2E, left column [red]), suggesting that AMs were only minimally activated by the presence of infected erythrocytes, recruited monocytes, and vascular leakage during acute malaria infection.

Although only a low number of MDMs were in the lungs of the uninfected mice (Fig. 2A), these cells were F4/80+MHCIIlow/midCD64low (Fig. 2E, right column [black]). In contrast to AMs, the MDMs from perfused lungs at d 6 displayed notably higher surface levels of F4/80, MHCII, CD40, CD80, CD86, PDL1, and CD64 (Fig. 2E, right column [red]) compared with the MDMs present in the lungs of the naïve mice. The recruited MDMs remained negative for SiglecF and PDL2. Additional analyses demonstrated that the vast majority of the activated MDMs with elevated levels of MHCII, CD80, and PDL1 were also cells that showed evidence of phagocytic uptake of parasites (Fig. 2F). These results indicate that direct contact with the infected erythrocytes might be a requirement for full activation of the monocytes and MDMs that take up residence in the lungs during malaria infection.

Because the MDMs in the lungs were recruited from the peripheral circulation, we also assessed the activation status of blood‐derived monocytes at d 6 of infection. Blood‐derived monocytes increased expression of CD64, CD80, and PDL1 at d 6 (Supplemental Fig. 2A), with no evidence that they were participating in the clearance of infected erythrocytes (data not shown). Thus, the activation status of the blood‐derived monocytes was limited compared with that observed for lung‐associated MDMs (Supplemental Fig. 2C).

CCR2 deficiency impairs monocyte recruitment and parasite clearance from the lungs

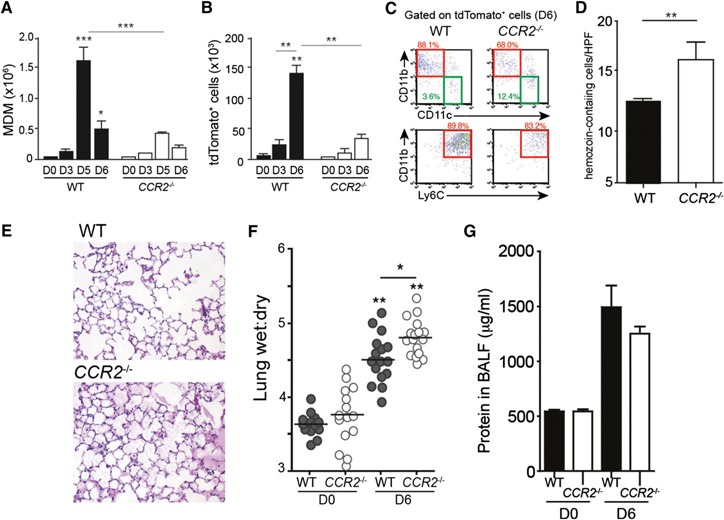

On the basis of the finding that MDMs appear to be responsible for the bulk of parasite uptake, we tested the hypothesis that impeding entry of monocytes into the lungs results in impaired parasite clearance. We used Ccr2−/− mice, which contain monocytes that cannot respond to several of the chemoattractant ligands expressed in the lungs after P. berghei infection (Supplemental Fig. 1I) [24]. Although the infection of Ccr2−/− mice with tdTPbA resulted in AM numbers (data not shown) and activation status (Supplemental Fig. 2E) comparable to those seen for the AMs from WT mice, the number of MDMs was greatly diminished in the lungs from the Ccr2−/− mice ( Fig. 3A ). Moreover, the few MDMs that were recruited to the lungs of the Ccr2−/− mice at d 6 of infection had a significantly diminished activation status compared with that observed in the WT mice (Supplemental Fig. 2F). Consistent with their lower numbers, significantly fewer MDMs containing tdTPbA were identified from the lungs of Ccr2−/− mice (Fig. 3B and C), despite equivalent levels of blood parasitemia (data not shown). This loss of MDM recruitment and parasite uptake was associated with increased hemozoin accumulation and pathologic features on examination of the histologic sections (Fig. 3D and E). This apparent exacerbated loss of endothelial barrier integrity appeared to be associated with augmented fluid flux, because the lung wet:dry ratio was significantly elevated in Ccr2 −/− mice, but the total protein in the BAL fluid was not different than that of the WT controls (Fig. 2F and G). These results suggest that recruited monocytes and MDMs play a role in restricting the extent of pathologic features by regulating parasite sequestration and subsequent perturbations to endothelial fluid conductance.

Figure 3.

CCR2 deficiency results in altered cell trafficking, reduced parasite clearance, and lung injury. (A) Total numbers of MDMs (CD64+CD11b+CD11c−) in the lungs of WT C57BL/6 (filled) or Ccr2−/− (open) mice at days 0 (D0), 3 (D3), 5 (D5), and 6 (D6) after P. berghei infection. (B) Total number of mononuclear cells positive for tdTomato signal at D3, D5, and D6 after tdTPbA infection for WT (filled) or Ccr2−/− (open) mice. Data in the bar graphs are mean ± sem; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (n = 3–5). Comparisons versus noninfected control, except as noted by comparison line. (C) Representative flow cytometric analysis of the distribution of the tdTomato signal at D6 after infection associated with cells expressing CD11b, CD11c, and Ly6C in the lungs of WT and Ccr2 −/− mice. (D) Number of hemozoin‐containing cells in the lungs of WT and Ccr2−/− mice at D6 of infection (n = 3 mice at 10 fields per mouse). (E) Representative histologic sections (magnification ×10) of lung tissue from WT or Ccr2−/− mice at D6 of infection with P. berghei ANKA. (F) Wet:dry ratios of lungs harvested at D0 and D6 from WT and Ccr2 −/− mice (n = 18). Horizontal line denotes mean. (G) Protein concentration in BAL fluid collected at D0 and D6 from WT and CCR2−/− lungs. Data are representative of 3 independent repetitions; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

CD36 and malaria‐induced ALI

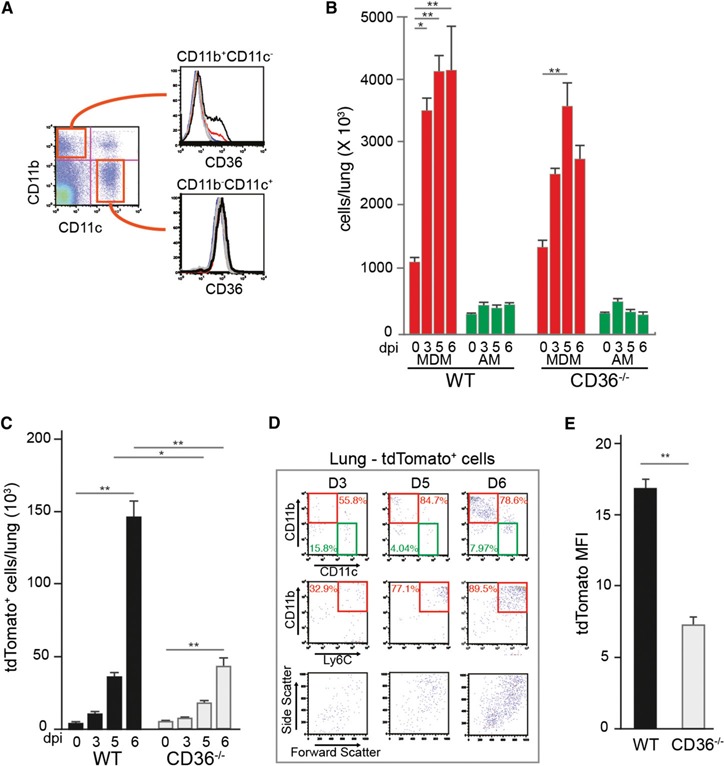

The scavenger receptor CD36 is expressed on lung vascular endothelial cells, where it mediates the sequestration of malaria‐infected erythrocytes [13, 37, 38], and on the surface of mononuclear cells, where it serves as a receptor for nonopsonic phagocytosis of Plasmodium‐infected erythrocytes [39, 40–41]. Although the importance of CD36 in the sequestration of parasitized erythrocytes to endothelial surfaces in the lungs has been demonstrated [16], the role of CD36 on myeloid cell populations in controlling malaria‐associated respiratory distress is less clearly defined. In the lung environment, MDMs are CD36+ but AMs do not express detectable levels of CD36 ( Fig. 4A ).

Figure 4.

Dynamics of mononuclear cells and parasite clearance in the lungs from Cd36−/− mice. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of CD36 on the surface of CD11b+CD11c− and CD11b−CD11c+ cells in the lungs. (B) Dynamics of CD64+CD11b+CD11c− MDMs and CD64+CD11b−CD11c+ AMs in WT and Cd36−/− lungs during tdTPbA infection. The numbers were derived from flow cytometric analysis of whole perfused lungs obtained at days 3 (D3), 5 (D5), and 6 (D6) after infection. (C) The number of tdTomato‐positive cells from the perfused lungs of WT and Cd36−/− mice at D0, D3, D5, and D6 after infection. (D) Representative flow cytometry data depicting the dynamics of uptake of tdTPbA‐infected erythrocytes by CD11b+CD11c−Ly6Chi MDMs and CD11b−CD11c+Ly6Clo AMs from perfused Cd36 −/− lungs at D3, D5, and D6 after infection. Dot plots in the bottom row depict the light scatter properties of the tdTomato‐positive cells present in each population. (E) The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for tdTomato‐positive cells detected in perfused lungs from WT and Cd36−/− mice at D6 after infection. Data are representative of 2–3 independent repetitions. All data are mean ± sem (n = 3–5); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

To determine the contribution of CD36 to the overall response in the lungs, we infected CD36−/− mice with tdTPbA and assessed them for temporal changes in AMs and MDMs. Just as observed for the WT mice, infection resulted in a significant increase in MDMs and no change in the number of AMs (Fig. 4B). Although a trend was seen for fewer MDMs at each day tested, the numbers in the Cd36−/− mice were not significantly different from those in the WT lungs. As expected, the absence of CD36‐mediated sequestration and phagocytosis resulted in significantly fewer MDMs that had engulfed tdTPbA parasitic material (Fig. 4C). Of the cells from the Cd36−/− lungs that did contain tdTomato signal, 80–90% were CD11b+Ly6c+ MDMs (Fig. 4D), a proportion similar to that observed in the WT lungs (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, on a per cell basis, the lower tdTomato mean fluorescence intensity suggests that the phagocytically active Cd36−/− MDMs engulfed fewer parasites (Fig. 4E).

The AMs from the Cd36−/− mice at d 0 and 6 of infection had nearly identical surface phenotypes to the AMs from the WT mice (Fig. 2E and Supplemental Fig. 2G). Also, although lacking a CD36‐mediated mechanism to engulf parasitized erythrocytes, the Cd36−/− MDMs that did take up parasites had an activation profile closely resembling that observed for the phagocytically active WT MDMs (Supplemental Fig. 2C and D, blue).

To determine the relative contributions of endothelial cell‐ and mononuclear cell‐associated CD36 to malaria‐induced lung pathologic features, we generated CD36 chimeric mice, where CD36 expression was restricted to either vascular endothelial cells or cells of hematopoietic origin (Supplemental Fig. 3A). On P. berghei infection, the Cd36−/− > WT group had elevated parasitemia at d 5 and 6 compared with that of other chimeric groups (Supplemental Fig. 3B).

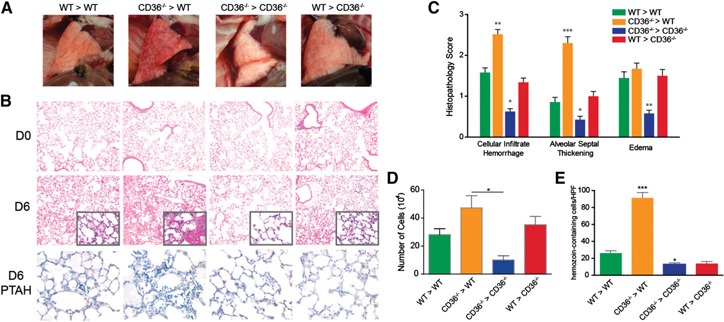

The gross appearance of the lungs from mice in which CD36 was expressed on endothelial cells (Cd36−/− > WT) was markedly red and inflamed compared with the appearance of the lungs from mice that expressed CD36 on cells of hematopoietic origin but not on vascular endothelial cells (WT > Cd36−/−; Fig. 5A ). This observation was in contrast to the lungs derived from Cd36−/− > Cd36−/− controls, which consistently appeared the least congested and inflamed. The outward appearance of the lungs was reflected in the intensity of the cellular infiltrate in the airways (Fig. 5D). Consistent with the importance of CD36 for the ability of MDMs to clear malaria‐infected erythrocytes [15, 40, 41], the Cd36−/− > WT mice showed evidence of significantly greater parasite exposure in the lungs (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5.

Malaria‐induced pathologic findings in the lungs of Cd36−/− bone marrow chimeras. (A) Gross appearance of lungs from CD36 bone marrow chimeric mice at day 6 (D6) after P. berghei ANKA infection. (B) Representative (n = 3) histologic sections of lungs from noninfected D0 or D6 after infection WT > WT, Cd36−/− > WT, Cd36−/− > Cd36−/− or WT > Cd36−/− bone marrow chimeric mice (n = 3). Sections were stained with H&E (top and middle rows) (magnification ×10) or Mallory's phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin (PTAH) (bottom row) (magnification ×60). (C) Histopathological scoring of intra‐alveolar inflammatory infiltrates/hemorrhage, alveolar septal thickening, and alveolar edema in the lungs of mice from the 4 transfer groups at D6 after P. berghei infection. Data are presented as the mean ± se (n = 24–56 slides per group). *Comparisons different from WT > WT. (D) Number of mononuclear cells isolated in BAL of P. berghei‐infected mice at D6 from each bone marrow chimera transfer group. (E) The number of hemozoin‐containing cells per high power field (HPF) in the 4 bone marrow chimera transfer groups. Data are presented as mean ± se (n = 2 mice per group and 10 HPFs per lung). Data are representative of 2 independent repetitions. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Histologic analysis showed that the lungs from the Cd36−/− > WT mice exhibited markedly more malaria‐induced pulmonary pathologic features (Fig. 5B, center). The lungs of the Cd36−/− > WT mice displayed areas of widespread edema, focal regions of erythrocyte and inflammatory cell leakage into the air spaces, and extensive thickening of alveolar walls (Fig. 5C). The WT > WT and WT > Cd36−/− groups showed similar forms of lung injury, but to a lesser extent. In contrast, the lungs from the Cd36−/− > Cd36−/− group exhibited the lowest levels of malaria‐induced lung inflammation. Additionally, staining for intra‐alveolar fibrin, a pathologic hallmark of ALI [43], revealed that the highest levels of fibrin production were in the lungs that expressed CD36 only on the vascular endothelial cells (Cd36−/− > WT; Fig. 5B, bottom row).

DISCUSSION

The present work has identified CCR2+CD11b+Ly6Chi monocytes, which remain within pulmonary tissues as MDMs, as the critical cell type that mediates clearance of Plasmodium‐infected erythrocytes from the lung. The significance of CCR2+CD11b+Ly6Chi monocytes as innate effector cells during blood‐stage malaria has previously been studied in the context of the spleen during P. chabaudi infection in mice [23]. That study demonstrated that a population of CD11bhighLy6C+ monocytes migrate from the bone marrow to the spleen in a CCR2‐dependent manner during infection and effectively limits acute stage parasitemia. Similar to the present results for monocytes recruited to the lungs, CCR2+CD11bhiLy6C+ splenic monocytes readily engulf malaria‐infected erythrocytes and upregulate the surface markers associated with cell activation and antigen presentation. Although the monocytes recruited to the spleen express molecules suggesting a potential for antigen presentation, they are significantly less efficient than dendritic cells at antigen presentation [23]. In future work, it will be of interest to track the postphagocytic fate of the lung MDMs and determine whether they participate in shaping the nature and level of the T cell response to malaria antigens.

AMs, similar to other tissue‐resident macrophages such as Kupffer cells in the liver, glial cells in the central nervous system, and osteoclasts in bone, have distinct functional characteristics that are shaped by their local environment [44]. Recent studies have revealed that tissue‐resident macrophages are seeded before birth [45, 46, 46, 47–48] and have a capacity for in situ self‐renewal to maintain steady‐state levels [47, 48], for replacement after depletion [49], and in response to infections [50, 51]. In disease settings, this ability of tissue‐resident macrophages to proliferate has prompted a reevaluation of how we interpret the functional dynamics of mononuclear phagocytes at sites of inflammation and the functional roles assigned to AMs and monocyte‐derived cells recruited to inflamed tissues. In the absence of disease, AMs are vital components of the homeostatic mechanism that prevents pulmonary inflammation to common environmental exposures (reviewed in [52]). In the context of acute malaria infection in the lungs, the AMs, which showed little evidence of activation and no evidence of proliferation (Fig. 2A and E), appear to have only a minor role in responding to parasite sequestration in the pulmonary vasculature. The AMs retained their apparent nonactivated status even under conditions of CCR2 deficiency, in which blunted monocyte recruitment resulted in an elevated parasite burden and exacerbated lung reactivity (Supplemental Fig. 2). It is likely, given that the chief role of AMs is to respond to challenges within the alveolar spaces, that as long as malaria‐infected cells remain in the vascular compartment (or within the phagosomes of MDMs), the AMs do not receive the required activation signals. Alternatively, it is possible that the surface markers we used in the present study do not capture the changes in the activation status of AMs or that AMs are playing an anti‐inflammatory/pro‐homeostatic role aimed at modulating the degree of malaria‐induced pulmonary inflammation.

This lack of AM responsiveness during malaria infection is in contrast to the proliferation observed in response to helminth and virus challenge within the lungs [47, 51]. The lack of proliferation could reflect an absence of proper signals during the acute phase of infection. Both larval helminth parasites and influenza virus infection result in considerable lung epithelial cell damage and the release of danger‐associated molecular patterns, alarmins, or other signaling molecules that could serve as a cue for AM proliferation. During the early stages of malaria infection in the lungs, no evidence was found of epithelial cell damage or hemorrhage to suggest endothelial cell injury. IL‐4, one of the factors shown to induce pericardial and peritoneal macrophages to proliferate [50, 53], was not detected during the early phase of P. berghei infection in C57BL/6 mice (data not shown). Although it is clear that AMs have the capacity to rapidly expand in response to pathogen challenge [51], it could be that AM proliferation is delayed during malaria until the latter phases of the infection. Additional work is required to assign a functional role for the AMs during innate and adaptive immunity during malaria infection.

The scavenger receptor, CD36, plays several important roles in P. berghei infection. CD36 is expressed on lung vascular endothelial cells, where it serves as a binding partner with an as yet to be identified parasite ligand deployed on the surface of infected cells. Recent data suggest that this unknown surface ligand might interact directly or indirectly with the parasite‐derived schizont membrane‐associated cytoadherence protein that is exported to the cytoplasm of infected erythrocytes [13]. CD36 is also expressed on the surface of macrophages and monocytes, where it serves as a receptor that mediates the recognition and phagocytosis of infected erythrocytes [39, 40–41]. Most of the reports that used Cd36−/− animals to study malaria in the lungs observed a significant reduction in the lung parasite burden and ALI [15, 16] but could not differentiate the contributions of the endothelial cell‐expressed and monocyte/macrophage‐expressed CD36 to the phenotype. The single report that used a bone marrow chimera approach similar to the one we used, concluded, based only on the survival data, that CD36 on nonhematopoietic cells is harmful [12]. The work we have presented, using Ccr2−/−, Cd36−/−, and bone marrow chimeric mice, offers a cellular mechanism for this observation. Our results are consistent with a basic model in which the degree of malaria‐induced lung pathologic features is proportional to the steady‐state levels of infected erythrocytes adhering to the pulmonary vasculature, which, in turn, is influenced by the relative level and efficiency of CD36‐mediated clearance of sequestered parasites by recruited MDMs. Still to be determined is the degree to which the activated MDMs and their local release of cytokines influence the level of lung injury during the innate response to malaria.

We have previously reported on the differential changes in 2 measures of lung endothelial barrier function—paracellular fluid conductance and serum protein reflection—during malaria infection [20]. Although P. berghei‐infected WT and CD36−/− lungs were found to have comparable levels of protein influx, only the CD36−/− lungs maintained the endothelial barrier to fluid entry. The levels of protein in the edema from infected CCR2−/− lungs indicate that the barriers to protein translocation in WT and CCR2−/− are compromised to a similar extent (Fig. 3G); however, the fluid flux is enhanced in CCR2−/− lungs (Fig. 3E and F). The mechanism underlying these selective barrier changes in WT, CD36−/−, and CCR2−/− lungs remains unclear, but it could be due to differential perturbation of the sieving properties of the vascular glycocalyx in response to adhering infected erythrocytes and/or endothelial responses to cytokines produced by activated MDMs [54, 55–56]. The notion that cytoadherence contributes to the selective barrier changes is supported further by the observation in the bone marrow chimera mice that the level of edema in infected WT > CD36−/− lungs was equivalent to that of the infected WT > WT controls (Fig 5C).

A possible insight into the contribution that MDM activation status has on malaria‐induced lung inflammation is provided by the results of the bone marrow chimera experiment. Although the histologic and parasitological phenotypes of the Cd36−/− > Cd36−/−, Cd36−/− > WT, and WT > WT groups are consistent with the adhesion‐induced damage model, the histologic phenotype of the WT > Cd36−/− chimera group suggests that additional factors might contribute to the lung inflammation. The model predicts that parasite‐infected cells would be unable to adhere to the vasculature in the WT > Cd36−/− lungs owing to the lack of CD36 and that this would result in a phenotype similar to that observed for the Cd36−/− > Cd36−/− lungs. Instead, the lungs appear to be inflamed. Although it is clear from a number of reports that interaction with CD36 is a dominate mechanism for adherence to lung vasculature [13, 15, 16, 20], it is likely that P. berghei ANKA, similar to P. falciparum, has evolved alternate modes of cell–cell interaction that result in low‐level adherence to endothelial cells. A low level of binding was noted in both the Cd36−/− > Cd36−/− and the WT > Cd36−/− groups (data not shown). It is possible that this low‐level parasite adherence, although not sufficient to induce lung inflammation in the absence of MDM phagocytosis and activation, such as in Cd36−/− > Cd36−/− lungs, is enough to activate the MDMs to produce cytokines and reactive oxygen species that result in a histopathologic phenotype resembling that observed in the WT > WT lungs.

The findings we have presented will help to elucidate the possible complications of using agents that alter the CD36 levels as adjunct therapy for patients with severe malaria. Some of these approaches aim to reduce malaria‐induced pathologic features by increasing parasite clearance using peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐γ [57, 58] and Nrf2 agonists [59] to pharmacologically upregulate CD36 levels on the surface of monocytes and macrophages. In addition, other anti‐adhesion blocking therapies focus on limiting the level of parasite sequestration through CD36 blockade (reviewed in [60]). For example, the anti‐helminthic drug levamisole limits CD36‐mediated sequestration of Plasmodium‐infected erythrocytes by blocking CD36 dephosphorylation and preventing the high‐affinity binding form of CD36 [61, 62]. As our data have demonstrated, the relative contributions of both parasite sequestration and monocyte clearance should be considered because both contribute to malaria‐induced lung injury (and possibly to injury at other tissue sites). Therefore, careful consideration is required when proposing pharmacologic alterations of CD36 levels as a method to increase parasite clearance, because such a strategy could have deleterious consequences on the extent of CD36‐mediated parasite sequestration. In contrast, therapeutic blockade of CD36‐mediated parasite sequestration might alter the ability of mononuclear phagocytes to effectively clear parasites via nonopsonic phagocytosis.

AUTHORSHIP

H.A.D.L. performed histologic, flow cytometric, and cytokine analyses +on WT, CCR2−/−, and CD36−/− mice and helped write the manuscript. I.U.A. performed histologic, flow cytometric, and cytokine analyses on WT, CD36−/−, and bone marrow chimeric mice and helped write the manuscript. J.M.C created the experimental design, provided experimental assistance, and analyzed the data and helped write the manuscript. A.K.P. performed flow cytometric and histologic analysis after sporozoite challenge and helped write the manuscript. N.L. and W.M. generated and analyzed the lung function data and helped write the manuscript. A.L.S. supervised the overall project and helped write the manuscript.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Grant P01HL10342) to W.M. and A.L.S. and by a pilot grant from the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute to A.L.S. H.A.D.L. and I.U.A. were supported by JHMRI fellowships, N.L. by a King Rama VIII's scholarship from the Anandamahidol Foundation, and J.M.C. by an NHLBI fellowship (Award F32HL124823). The content of our report is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NHLBI or the NIH. The authors thank Dr. Maria Febrraio for providing the Cd36−/− mice, the Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center for providing the P. berghei ANKA parasites, Dr. Volker Heussler for providing tdTomato‐transgenic P. berghei ANKA, Dr. Robert Thacker for his assistance with the Amnis ImageStreamX Mark II, Xin Guo for her assistance with tissue processing for histologic examination, and Diego Espinosa and Photini Sinnis for their assistance with sporozoite challenges.

Footnotes

SEE CORRESPONDING EDITORIAL ON PAGE 643

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. (2013) World Malaria Report, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murray, C. J. , Vos, T. , Lozano, R. , Naghavi, M. , Flaxman, A. D. , Michaud, C. , Ezzati, M. , Shibuya, K. , Salomon, J. A. , Abdalla, S. , Aboyans, V. , Abraham, J. , Ackerman, I. , Aggarwal, R. , Ahn, S. Y. , Ali, M. K. , Alvarado, M. , Anderson, H. R. , Anderson, L. M. , Andrews, K. G. , Atkinson, C. , Baddour, L. M. , Bahalim, A. N. , Barker‐Collo, S. , Barrero, L. H. , Bartels, D. H. , Basáñez, M. G. , Baxter, A. , Bell, M. L. , Benjamin, E. J. , Bennett, D. , Bernabé E., Bhalla, K. , Bhandari, B. , Bikbov, B. , Bin Abdulhak, A. , Birbeck, G. , Black, J. A. , Blencowe, H. , Blore, J. D. , Blyth, F. , Bolliger, I. , Bonaventure, A. , Boufous, S. , Bourne, R. , Boussinesq, M. , Braithwaite, T. , Brayne, C. , Bridgett, L. , Brooker, S. , Brooks, P. , Brugha, T. S. , Bryan‐Hancock, C. , Bucello, C. , Buchbinder, R. , Buckle, G. , Budke, C. M. , Burch, M. , Burney, P. , Burstein, R. , Calabria, B. , Campbell, B. , Canter, C. E. , Carabin, H. , Carapetis, J. , Carmona, L. , Cella, C. , Charlson, F. , Chen, H. , Cheng, A. T. , Chou, D. , Chugh, S. S. , Coffeng, L. E. , Colan, S. D. , Colquhoun, S. , Colson, K. E. , Condon, J. , Connor, M. D. , Cooper, L. T. , Corriere, M. , Cortinovis, M. , de Vaccaro, K. C. , Couser, W. , Cowie, B. C. , Criqui, M. H. , Cross, M. , Dabhadkar, K. C. , Dahiya, M. , Dahodwala, N. , Damsere‐Derry, J. , Danaei, G. , Davis, A. , De Leo, D. , Degenhardt, L. , Dellavalle, R. , Delossantos, A. , Denenberg, J. , Derrett, S. , Des Jarlais, D. C. , Dharmaratne, S. D. , Dherani, M. , Diaz‐Torne, C. , Dolk, H. , Dorsey, E. R. , Driscoll, T. , Duber, H. , Ebel, B. , Edmond, K. , Elbaz, A. , Ali, S. E. , Erskine, H. , Erwin, P. J. , Espindola, P. , Ewoigbokhan, S. E. , Farzadfar, F. , Feigin, V. , Felson, D. T. , Ferrari, A. , Ferri, C. P. , Fèvre, E. M. , Finucane, M. M. , Flaxman, S. , Flood, L. , Foreman, K. , Forouzanfar, M. H. , Fowkes, F. G. , Fransen, M. , Freeman, M. K. , Gabbe, B. J. , Gabriel, S. E. , Gakidou, E. , Ganatra, H. A. , Garcia, B. , Gaspari, F. , Gillum, R. F. , Gmel, G. , Gonzalez‐Medina, D. , Gosselin, R. , Grainger, R. , Grant, B. , Groeger, J. , Guillemin, F. , Gunnell, D. , Gupta, R. , Haagsma, J. , Hagan, H. , Halasa, Y. A. , Hall, W. , Haring, D. , Haro, J. M. , Harrison, J. E. , Havmoeller, R. , Hay, R. J. , Higashi, H. , Hill, C. , Hoen, B. , Hoffman, H. , Hotez, P. J. , Hoy, D. , Huang, J. J. , Ibeanusi, S. E. , Jacobsen, K. H. , James, S. L. , Jarvis, D. , Jasrasaria, R. , Jayaraman, S. , Johns, N. , Jonas, J. B. , Karthikeyan, G. , Kassebaum, N. , Kawakami, N. , Keren, A. , Khoo, J. P. , King, C. H. , Knowlton, L. M. , Kobusingye, O. , Koranteng, A. , Krishnamurthi, R. , Laden, F. , Lalloo, R. , Laslett, L. L. , Lathlean, T. , Leasher, J. L. , Lee, Y. Y. , Leigh, J. , Levinson, D. , Lim, S. S. , Limb, E. , Lin, J. K. , Lipnick, M. , Lipshultz, S. E. , Liu, W. , Loane, M. , Ohno, S. L. , Lyons, R. , Mabweijano, J. , MacIntyre, M. F. , Malekzadeh, R. , Mallinger, L. , Manivannan, S. , Marcenes, W. , March, L. , Margolis, D. J. , Marks, G. B. , Marks, R. , Matsumori, A. , Matzopoulos, R. , Mayosi, B. M. , McAnulty, J. H. , McDermott, M. M. , McGill, N. , McGrath, J. , Medina‐Mora, M. E. , Meltzer, M. , Mensah, G. A. , Merriman, T. R. , Meyer, A. C. , Miglioli, V. , Miller, M. , Miller, T. R. , Mitchell, P. B. , Mock, C. , Mocumbi, A. O. , Moffitt, T. E. , Mokdad, A. A. , Monasta, L. , Montico, M. , Moradi‐Lakeh, M. , Moran, A. , Morawska, L. , Mori, R. , Murdoch, M. E. , Mwaniki, M. K. , Naidoo, K. , Nair, M. N. , Naldi, L. , Narayan, K. M. , Nelson, P. K. , Nelson, R. G. , Nevitt, M. C. , Newton, C. R. , Nolte, S. , Norman, P. , Norman, R. , O'Donnell, M. , O'Hanlon, S. , Olives, C. , Omer, S. B. , Ortblad, K. , Osborne, R. , Ozgediz, D. , Page, A. , Pahari, B. , Pandian, J. D. , Rivero, A. P. , Patten, S. B. , Pearce, N. , Padilla, R. P. , Perez‐Ruiz, F. , Perico, N. , Pesudovs, K. , Phillips, D. , Phillips, M. R. , Pierce, K. , Pion, S. , Polanczyk, G. V. , Polinder, S. , Pope, III, C. A. , Popova, S. , Porrini, E. , Pourmalek, F. , Prince, M. , Pullan, R. L. , Ramaiah, K. D. , Ranganathan, D. , Razavi, H. , Regan, M. , Rehm, J. T. , Rein, D. B. , Remuzzi, G. , Richardson, K. , Rivara, F. P. , Roberts, T. , Robinson, C. , De Leòn, F. R. , Ronfani, L. , Room, R. , Rosenfeld, L. C. , Rushton, L. , Sacco, R. L. , Saha, S. , Sampson, U. , Sanchez‐Riera, L. , Sanman, E. , Schwebel, D. C. , Scott, J. G. , Segui‐Gomez, M. , Shahraz, S. , Shepard, D. S. , Shin, H. , Shivakoti, R. , Singh, D. , Singh, G. M. , Singh, J. A. , Singleton, J. , Sleet, D. A. , Sliwa, K. , Smith, E. , Smith, J. L. , Stapelberg, N. J. , Steer, A. , Steiner, T. , Stolk, W. A. , Stovner, L. J. , Sudfeld, C. , Syed, S. , Tamburlini, G. , Tavakkoli, M. , Taylor, H. R. , Taylor, J. A. , Taylor, W. J. , Thomas, B. , Thomson, W. M. , Thurston, G. D. , Tleyjeh, I. M. , Tonelli, M. , Towbin, J. A. , Truelsen, T. , Tsilimbaris, M. K. , Ubeda, C. , Undurraga, E. A. , van der Werf, M. J. , van Os, J. , Vavilala, M. S. , Venketasubramanian, N. , Wang, M. , Wang, W. , Watt, K. , Weatherall, D. J. , Weinstock, M. A. , Weintraub, R. , Weisskopf, M. G. , Weissman, M. M. , White, R. A. , Whiteford, H. , Wiebe, N. , Wiersma, S. T. , Wilkinson, J. D. , Williams, H. C. , Williams, S. R. , Witt, E. , Wolfe, F. , Woolf, A. D. , Wulf, S. , Yeh, P. H. , Zaidi, A. K. , Zheng, Z. J. , Zonies, D. , Lopez, A. D. , Al Mazroa, M. A. , Memish, Z. A. (2012) Disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990‐2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380, 2197–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Idro, R. , Marsh, K. , John, C. C. , Newton, C. R. (2010) Cerebral malaria: mechanisms of brain injury and strategies for improved neurocognitive outcome. Pediatr. Res. 68, 267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Menendez, C. , Ordi, J. , Ismail, M. R. , Ventura, P. J. , Aponte, J. J. , Kahigwa, E. , Font, F. , Alonso, P. L. (2000) The impact of placental malaria on gestational age and birth weight. J. Infect. Dis. 181, 1740–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mohan, A. , Sharma, S. K. , Bollineni, S. (2008) Acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome in malaria. J. Vector Borne Dis. 45, 179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Asiedu, D. K. , Sherman, C. B. (2000) Adult respiratory distress syndrome complicating Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Heart Lung 29, 294–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aursudkij, B. , Wilairatana, P. , Vannaphan, S. , Walsh, D. S. , Gordeux, V. R. , Looareesuwan, S. (1998) Pulmonary edema in cerebral malaria patients in Thailand. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 29, 541–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taylor, W. R. , Hanson, J. , Turner, G. D. , White, N. J. , Dondorp, A. M. (2012) Respiratory manifestations of malaria. Chest 142, 492–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization . 2010. Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taylor, W. R. , Cañon, V. , White, N. J. (2006) Pulmonary manifestations of malaria: recognition and management. Treat. Respir. Med. 5, 419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buffet, P. A. , Safeukui, I. , Deplaine, G. , Brousse, V. , Prendki, V. , Thellier, M. , Turner, G. D. , Mercereau‐Puijalon, O. (2011) The pathogenesis of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in humans: insights from splenic physiology. Blood 117, 381–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cunha‐Rodrigues, M. , Portugal, S. , Febbraio, M. , Mota, M. M. (2007) Bone marrow chimeric mice reveal a dual role for CD36 in Plasmodium berghei ANKA infection. Malar. J. 6, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fonager, J. , Pasini, E. M. , Braks, J. A. M. , Klop, O. , Ramesar, J. , Remarque, E. J. , Vroegrijk, I. O. C. M. , van Duinen, S. G. , Thomas, A. W. , Khan, S. M. , Mann, M. , Kocken, C. H. M. , Janse, C. J. , Franke‐Fayard, B. M. D. (2012) Reduced CD36‐dependent tissue sequestration of Plasmodium‐infected erythrocytes is detrimental to malaria parasite growth in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 209, 93–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Franke‐Fayard, B. , Fonager, J. , Braks, A. , Khan, S. M. , Janse, C. J. (2010) Sequestration and tissue accumulation of human malaria parasites: can we learn anything from rodent models of malaria? PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Franke‐Fayard, B. , Janse, C. J. , Cunha‐Rodrigues, M. , Ramesar, J. , Büscher, P. , Que, I. , Löwik, C. , Voshol, P. J. , den Boer, M. A. , van Duinen, S. G. , Febbraio, M. , Mota, M. M. , Waters, A. P. (2005) Murine malaria parasite sequestration: CD36 is the major receptor, but cerebral pathology is unlinked to sequestration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11468–11473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lovegrove, F. E. , Gharib, S. A. , Peña‐Castillo, L. , Patel, S. N. , Ruzinski, J. T. , Hughes, T. R. , Liles, W. C. , Kain, K. C. (2008) Parasite burden and CD36‐mediated sequestration are determinants of acute lung injury in an experimental malaria model. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van den Steen, P. E. , Geurts, N. , Deroost, K. , Van Aelst, I. , Verhenne, S. , Heremans, H. , Van Damme, J. , Opdenakker, G. (2010) Immunopathology and dexamethasone therapy in a new model for malaria‐associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 181, 957–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Franke‐Fayard, B. , Waters, A. P. , Janse, C. J. (2006) Real‐time in vivo imaging of transgenic bioluminescent blood stages of rodent malaria parasites in mice. Nat. Protoc. 1, 476–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grüring, C. , Heiber, A. , Kruse, F. , Ungefehr, J. , Gilberger, T. W. , Spielmann, T. (2011) Development and host cell modifications of Plasmodium falciparum blood stages in four dimensions. Nat. Commun. 2, 165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anidi, I. U. , Servinsky, L. E. , Rentsendorj, O. , Stephens, R. S. , Scott, A. L. , Pearse, D. B. (2013) CD36 and Fyn kinase mediate malaria‐induced lung endothelial barrier dysfunction in mice infected with Plasmodium berghei . PLoS One 8, e71010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Good, M. F. , Doolan, D. L. (2010) Malaria vaccine design: immunological considerations. Immunity 33, 555–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chua, C. L. , Brown, G. , Hamilton, J. A. , Rogerson, S. , Boeuf, P. (2013) Monocytes and macrophages in malaria: protection or pathology? Trends Parasitol. 29, 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sponaas, A. M. , Freitas do Rosario, A. P. , Voisine, C. , Mastelic, B. , Thompson, J. , Koernig, S. , Jarra, W. , Renia, L. , Mauduit, M. , Potocnik, A. J. , Langhorne, J. (2009) Migrating monocytes recruited to the spleen play an important role in control of blood stage malaria. Blood 114, 5522–5531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boring, L. , Gosling, J. , Chensue, S. W. , Kunkel, S. L. , Farese Jr., R. V. , Broxmeyer, H. E. , Charo, I. F. (1997) Impaired monocyte migration and reduced type 1 (Th1) cytokine responses in C‐C chemokine receptor 2 knockout mice. J. Clin. Invest. 100, 2552–2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Febbraio, M. , Abumrad, N. A. , Hajjar, D. P. , Sharma, K. , Cheng, W. , Pearce, S. F. , Silverstein, R. L. (1999) A null mutation in murine CD36 reveals an important role in fatty acid and lipoprotein metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19055–19062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Graewe, S. , Retzlaff, S. , Struck, N. , Janse, C. J. , Heussler, V. T. (2009) Going live: a comparative analysis of the suitability of the RFP derivatives RedStar, mCherry and tdTomato for intravital and in vitro live imaging of Plasmodium parasites. Biotechnol. J. 4, 895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Espinosa, D. A. , Gutierrez, G. M. , Rojas‐López, M. , Noe, A. R. , Shi, L. , Tse, S. W. , Sinnis, P. , Zavala, F. (2015) Proteolytic cleavage of the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein is a target of protective antibodies. J. Infect. Dis. 212, 1111–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reece, J. J. , Siracusa, M. C. , Scott, A. L. (2006) Innate immune responses to lung‐stage helminth infection induce alternatively activated alveolar macrophages. Infect. Immun. 74, 4970–4981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee, M. A. , Tan, C. H. , Aw, L. T. , Tang, C. S. , Singh, M. , Lee, S. H. , Chia, H. P. , Yap, E. P. (2002) Real‐time fluorescence‐based PCR for detection of malaria parasites. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40, 4343–4345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Garcia, A. N. , Vogel, S. M. , Komarova, Y. A. , Malik, A. B. (2011) Permeability of endothelial barrier: cell culture and in vivo models. Methods Mol. Biol. 763, 333–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen, M. M. , Shi, L. , Sullivan, D. J., Jr. (2001) Haemoproteus and Schistosoma synthesize heme polymers similar to Plasmodium hemozoin and beta‐hematin. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 113, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fallica, J. , Das, S. , Horton, M. , Mitzner, W. (2011) Application of carbon monoxide diffusing capacity in the mouse lung. J. Appl. Physiol. 110, 1455–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matute‐Bello, G. , Downey, G. , Moore, B. B. , Groshong, S. D. , Matthay, M. A. , Slutsky, A. S. , Kuebler, W. M. ; (2011) An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: features and measurements of experimental acute lung injury in animals. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 44, 725–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shi, C. , Pamer, E. G. (2011) Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 762–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Misharin, A. V. , Morales‐Nebreda, L. , Mutlu, G. M. , Budinger, G. R. , Perlman, H. (2013) Flow cytometric analysis of macrophages and dendritic cell subsets in the mouse lung. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 49, 503–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zaynagetdinov, R. , Sherrill, T. P. , Kendall, P. L. , Segal, B. H. , Weller, K. P. , Tighe, R. M. , Blackwell, T. S. (2013) Identification of myeloid cell subsets in murine lungs using flow cytometry. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 49, 180–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Amante, F. H. , Haque, A. , Stanley, A. C. , Rivera Fde. L., Randall, L. M. , Wilson, Y. A. , Yeo, G. , Pieper, C. , Crabb, B. S. , de Koning‐Ward, T. F. , Lundie, R. J. , Good, M. F. , Pinzon‐Charry, A. , Pearson, M. S. , Duke, M. G. , McManus, D. P. , Loukas, A. , Hill, G. R. , Engwerda, C. R. (2010) Immune‐mediated mechanisms of parasite tissue sequestration during experimental cerebral malaria. J. Immunol. 185, 3632–3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ockenhouse, C. F. , Tegoshi, T. , Maeno, Y. , Benjamin, C. , Ho, M. , Kan, K. E. , Thway, Y. , Win, K. , Aikawa, M. , Lobb, R. R. (1992) Human vascular endothelial cell adhesion receptors for Plasmodium falciparum‐infected erythrocytes: roles for endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule 1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. J. Exp. Med. 176, 1183–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McGilvray, I. D. , Serghides, L. , Kapus, A. , Rotstein, O. D. , Kain, K. C. (2000) Nonopsonic monocyte/macrophage phagocytosis of Plasmodium falciparum‐parasitized erythrocytes: a role for CD36 in malarial clearance. Blood 96, 3231–3240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Patel, S. N. , Serghides, L. , Smith, T. G. , Febbraio, M. , Silverstein, R. L. , Kurtz, T. W. , Pravenec, M. , Kain, K. C. (2004) CD36 mediates the phagocytosis of Plasmodium falciparum‐infected erythrocytes by rodent macrophages. J. Infect. Dis. 189, 204–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Serghides, L. , Kain, K. C. (2001) Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma‐retinoid X receptor agonists increase CD36‐dependent phagocytosis of Plasmodium falciparum‐parasitized erythrocytes and decrease malaria‐induced TNF‐alpha secretion by monocytes/macrophages. J. Immunol. 166, 6742–6748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Erdman, L. K. , Cosio, G. , Helmers, A. J. , Gowda, D. C. , Grinstein, S. , Kain, K. C. (2009) CD36 and TLR interactions in inflammation and phagocytosis: implications for malaria. J. Immunol. 183, 6452–6459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Idell, S. (2003) Coagulation, fibrinolysis, and fibrin deposition in acute lung injury. Crit. Care Med. 31 (4:, Suppl), S213–S220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gordon, S. , Taylor, P. R. (2005) Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 953–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ginhoux, F. , Jung, S. (2014) Monocytes and macrophages: developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 392–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guilliams, M. , De Kleer, I. , Henri, S. , Post, S. , Vanhoutte, L. , De Prijck, S. , Deswarte, K. , Malissen, B. , Hammad, H. , Lambrecht, B. N. (2013) Alveolar macrophages develop from fetal monocytes that differentiate into long‐lived cells in the first week of life via GM‐CSF. J. Exp. Med. 210, 1977–1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hashimoto, D. , Chow, A. , Noizat, C. , Teo, P. , Beasley, M. B. , Leboeuf, M. , Becker, C. D. , See, P. , Price, J. , Lucas, D. , Greter, M. , Mortha, A. , Boyer, S. W. , Forsberg, E. C. , Tanaka, M. , van Rooijen, N. , García‐Sastre, A. , Stanley, E. R. , Ginhoux, F. , Frenette, P. S. , Merad, M. (2013) Tissue‐resident macrophages self‐maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity 38, 792–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yona, S. , Kim, K. W. , Wolf, Y. , Mildner, A. , Varol, D. , Breker, M. , Strauss‐Ayali, D. , Viukov, S. , Guilliams, M. , Misharin, A. , Hume, D. A. , Perlman, H. , Malissen, B. , Zelzer, E. , Jung, S. (2013) Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity 38, 79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sawyer, R. T. , Strausbauch, P. H. , Volkman, A. (1982) Resident macrophage proliferation in mice depleted of blood monocytes by strontium‐89. Lab. Invest. 46, 165–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jenkins, S. J. , Ruckerl, D. , Cook, P. C. , Jones, L. H. , Finkelman, F. D. , van Rooijen, N. , MacDonald, A. S. , Allen, J. E. (2011) Local macrophage proliferation, rather than recruitment from the blood, is a signature of TH2 inflammation. Science 332, 1284–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Siracusa, M. C. , Reece, J. J. , Urban, Jr., J. F. , Scott, A. L. (2008) Dynamics of lung macrophage activation in response to helminth infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 84, 1422–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hussell, T. , Bell, T. J. (2014) Alveolar macrophages: plasticity in a tissue‐specific context. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 81–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jenkins, S. J. , Ruckerl, D. , Thomas, G. D. , Hewitson, J. P. , Duncan, S. , Brombacher, F. , Maizels, R. M. , Hume, D. A. , Allen, J. E. (2013) IL‐4 directly signals tissue‐resident macrophages to proliferate beyond homeostatic levels controlled by CSF‐1. J. Exp. Med. 210, 2477–2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Curry, F. R. , Adamson, R. H. (2010) Vascular permeability modulation at the cell, microvessel, or whole organ level: towards closing gaps in our knowledge. Cardiovasc. Res. 87, 218–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Michel, C. C. , Curry, F. E. (1999) Microvascular permeability. Physiol. Rev. 79, 703–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schmidt, E. P. , Yang, Y. , Janssen, W. J. , Gandjeva, A. , Perez, M. J. , Barthel, L. , Zemans, R. L. , Bowman, J. C. , Koyanagi, D. E. , Yunt, Z. X. , Smith, L. P. , Cheng, S. S. , Overdier, K. H. , Thompson, K. R. , Geraci, M. W. , Douglas, I. S. , Pearse, D. B. , Tuder, R. M. (2012) The pulmonary endothelial glycocalyx regulates neutrophil adhesion and lung injury during experimental sepsis. Nat. Med. 18, 1217–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Boggild, A. K. , Krudsood, S. , Patel, S. N. , Serghides, L. , Tangpukdee, N. , Katz, K. , Wilairatana, P. , Liles, W. C. , Looareesuwan, S. , Kain, K. C. (2009) Use of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma agonists as adjunctive treatment for Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49, 841–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Serghides, L. , Patel, S. N. , Ayi, K. , Lu, Z. , Gowda, D. C. , Liles, W. C. , Kain, K. C. (2009) Rosiglitazone modulates the innate immune response to Plasmodium falciparum infection and improves outcome in experimental cerebral malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 199, 1536–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Olagnier, D. , Lavergne, R. A. , Meunier, E. , Lefèvre, L. , Dardenne, C. , Aubouy, A. , Benoit‐Vical, F. , Ryffel, B. , Coste, A. , Berry, A. , Pipy, B. (2011) Nrf2, a PPARγ alternative pathway to promote CD36 expression on inflammatory macrophages: implication for malaria. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rowe, J. A. , Claessens, A. , Corrigan, R. A. , Arman, M. (2009) Adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum‐infected erythrocytes to human cells: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 11, e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ho, M. , Hoang, H. L. , Lee, K. M. , Liu, N. , MacRae, T. , Montes, L. , Flatt, C. L. , Yipp, B. G. , Berger, B. J. , Looareesuwan, S. , Robbins, S. M. (2005) Ectophosphorylation of CD36 regulates cytoadherence of Plasmodium falciparum to microvascular endothelium under flow conditions. Infect. Immun. 73, 8179–8187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dondorp, A. M. , Silamut, K. , Charunwatthana, P. , Chuasuwanchai, S. , Ruangveerayut, R. , Krintratun, S. , White, N. J. , Ho, M. , Day, N. P. (2007) Levamisole inhibits sequestration of infected red blood cells in patients with falciparum malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 196, 460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data