Both global and specific radiation damage have been investigated using three different proteins at cryogenic and room temperature. The large decoupling between global and specific radiation damage at cryogenic temperature appears to be practically abolished at room temperature, which has positive implications for time-resolved protein crystallography.

Keywords: room-temperature macromolecular crystallography, cryocrystallography, specific radiation damage, time-resolved crystallography

Abstract

Carrying out macromolecular crystallography (MX) experiments at cryogenic temperatures significantly slows the rate of global radiation damage, thus facilitating the solution of high-resolution crystal structures of macromolecules. However, cryo-MX experiments suffer from the early onset of so-called specific radiation damage that affects certain amino-acid residues and, in particular, the active sites of many proteins. Here, a series of MX experiments are described which suggest that specific and global radiation damage are much less decoupled at room temperature than they are at cryogenic temperatures. The results reported here demonstrate the interest in reviving the practice of collecting MX diffraction data at room temperature and allow structural biologists to favourably envisage the development of time-resolved MX experiments at synchrotron sources.

1. Introduction

Radiation damage in macromolecular crystallography (MX) experiments is an unavoidable phenomenon. In the early days of MX this meant that it was necessary to compile a complete diffraction data set from partial data sets collected from several crystals, making structure solution a very lengthy and arduous process (Perutz et al., 1960 ▸; Kendrew et al., 1960 ▸; Blake et al., 1965 ▸). The situation changed dramatically in the 1990s, when the advent of cryocooling (Hope, 1990 ▸; Garman & Schneider, 1997 ▸) greatly increased the absorbed dose that a crystal could tolerate before radiation damage destroyed its diffraction properties. This allowed the collection of complete, high-resolution diffraction data sets from a single crystal and paved the way for the explosion in the number and the types of macromolecular crystal structures that have been determined in the intervening quarter of a century. However, in the early 2000s a series of seminal papers (Ravelli & McSweeney, 2000 ▸; Burmeister, 2000 ▸; Weik et al., 2000 ▸) showed that it was not only global radiation damage that was the enemy of the crystallographer. Indeed, two types of radiation damage could be defined: (i) global damage, which is mainly observed in reciprocal space and corresponds to a degradation of the diffraction properties of a crystal, and (ii) specific damage, which is mainly observed in real space and corresponds to the photoreduction of metal centres, the photoreduction of photoactive protein chromophores, the breakage of covalent bonds (for example disulfide bridges) and/or the loss of electron density for the side chains of some amino acids. These two phenomena are largely decoupled at cryogenic temperature. While acceptable absorbed dose limits for global radiation damage have been proposed to be in the range 20–30 MGy (Henderson, 1995 ▸; Owen et al., 2006 ▸), specific radiation damage occurs at much lower absorbed doses [e.g. ∼7 kGy for the peroxo group in the active site of a reaction-intermediate state of urate oxidase (Bui et al., 2014 ▸), ∼60 kGy for alteration of the chromophore in bacteriorhodopsin (Borshchevskiy et al., 2014 ▸) and ∼1.6 MGy for the breakage of disulfide bonds in lysozyme (Carpentier et al., 2010 ▸)]. This decoupling of global and specific radiation damage often means that extreme care should be taken when interpreting the results of structures determined by MX, and experimenters must be sure that the electron-density maps produced do not contain artefacts arising from specific radiation damage. Most often, this means that MX should be complemented with in crystallo optical spectroscopy (icOS; von Stetten et al., 2015 ▸) or other measurements which provide information on the changes in the chemical state of a macromolecule that can be induced by exposure to X-rays.

In addition to the potential artefacts induced by specific radiation damage, a second potential pitfall of cryocrystallography is the fact that the cryocooling process can artificially trap biologically inactive conformations of amino-acid side chains. This can also lead to the misinterpretation of enzyme mechanisms and of the roles of particular amino acids in specific biological processes (Fraser et al., 2011 ▸). For this reason, room-temperature (RT) MX experiments are experiencing something of a renaissance. However, at RT the absorbed doses that induce global radiation damage can be two orders of magnitude lower than those at cryogenic temperatures (Nave & Garman, 2005 ▸; Southworth-Davies et al., 2007 ▸), and a thorough characterization of the radiation sensitivity of the crystals under study should usually be carried out if a complete data set is to be collected from a single crystal at room temperature. The question of whether the dose rate has an effect on radiation sensitivity at room temperature has been extensively investigated, but has not received a clear answer for dose rates covering 50 Gy s−1 to 680 kGy s−1 (Southworth-Davies et al., 2007 ▸; Rajendran et al., 2011 ▸; Owen et al., 2012 ▸; Warkentin et al., 2012 ▸; Leal et al., 2013 ▸). These investigations suggest, however, that the total absorbed dose has to be limited to a dose scale of hundreds of kilograys in order to record a complete data set, depending on the solvent content of the crystal (Leal et al., 2013 ▸).

In the course of studying the chromophore-photoswitching behaviour of the fluorescent protein Cerulean (Gotthard et al., 2017 ▸), we attempted to solve its room-temperature structure. Cerulean possesses a radiosensitive glutamate residue next to the chromophore, the side chain of which is severely affected by specific radiation damage (decarboxylation) during cryo-MX experiments. We thus expected this residue to be severely affected by specific radiation damage at RT. However, and to our surprise, the RT crystal structure that we obtained from a diffraction data set collected from a single crystal showed no sign of specific radiation damage. This prompted us to perform a more extensive study aimed at investigating specific radiation damage in room-temperature MX experiments. This topic was first considered by Southworth-Davies and coworkers when investigating the effects of various dose rates at room temperature (Southworth-Davies et al., 2007 ▸) and then by Russi and coworkers in the course of comparing structural heterogeneity at room and cryogenic temperatures (Russi et al., 2017 ▸). In both studies, it was observed that specific radiation damage was less obvious at room temperature than at cryogenic temperature. In this study, we recorded both X-ray diffraction data and, in order to obtain X-ray-independent estimates of specific radiation damage, complementary data using Raman or UV–Vis absorption spectroscopy. In addition to Cerulean, two other systems were studied: lysozyme, in order to examine the photoreduction of disulfide bonds at RT, and the photoadduct of the LOV2 domain of phototropin 2 from Arabidopsis thaliana, which upon light activation forms a covalent bond between the protein and its cofactor that is particularly sensitive to specific radiation damage at cryogenic temperatures. The results reported here suggest that specific and global radiation damage are much less decoupled at RT than they are at cryogenic temperature, thus confirming the interest in reviving the practice of collecting diffraction data at RT. They also allow structural biologists to favourably envisage the development of time-resolved MX experiments at synchrotron sources.

2. Methods

2.1. Protein expression and purification

Cerulean was overexpressed and purified using a previously described protocol (Lelimousin et al., 2009 ▸; Gotthard et al., 2017 ▸). Hen egg-white lysozyme (HEWL) was purchased from Roche Applied Science (catalogue No. 10837059001) and was dissolved in distilled water to a concentration of 40 mg ml−1. The gene coding for the LOV2 domain of phototropin 2 from A. thaliana (AtPhot2LOV2) was synthesized (GeneCust, Ellange, Luxembourg) and inserted into a pBAD plasmid. The plasmid was transformed into an Escherichia coli BL21 strain and the cells were grown in 2 l ZYP-5052 autoinducible medium (Studier, 2005 ▸) at 37°C until the OD600 nm reached 1.25. Protein expression was then induced with 0.2% l-arabinose for 14 h at 17°C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (20 min at 4000g) and the pellets were resuspended in 25 ml of a lysis buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 0.25 mg ml−1 lysozyme, 400 µg ml−1 DNAse I, 20 mM MgSO4 and protease-inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete EDTA-free, Roche) and frozen at −80°C. The resuspended pellets were sonicated four times for 30 s at 35 W power (VC-750 ultrasonic processor, Bioblock Scientific) and the cell debris was harvested by centrifugation (40 min at 15 000g at 4°C). The protein was purified from the clarified lysate using a nickel-affinity column (HisTrap HP 5 ml, GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, England) followed by size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex 75 10/300 GL, GE Healthcare). The purified AtPhot2LOV2 was concentrated to 5 mg ml−1 and subjected to digestion with trypsin (1 h, ratio of 1:100) prior to crystallization.

2.2. Protein crystallization

Cerulean was crystallized as described previously (Lelimousin et al., 2009 ▸; Gotthard et al., 2017 ▸) by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method (1:1 ratio in 2 µl drops) at 293 K using a protein concentration of 13 mg ml−1 in a condition consisting of 10–20% PEG 8000, 100 mM MgCl2, 100 mM HEPES pH 6.75–7.5. Needle-shaped crystals grew in five days and were used to seed subsequent optimized crystallization conditions (10–12% PEG 8000) by mixing the protein solution with the seed solution in a 1:10 or 1:100 ratio. Rod-shaped three-dimensional crystals then appeared after incubation for one week at 293 K. HEWL was crystallized using the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion method (1:1 ratio in 2 µl drops) in a crystallization condition consisting of 250–400 mM NaCl, 100 mM sodium acetate pH 4.8. Crystals belonging to the tetragonal space group P43212 grew at 293 K within one week. AtPhot2LOV2 was crystallized by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method (1:1 ratio in 2 µl drops) at 293 K using the protein at a concentration of 5 mg ml−1. Crystals appeared after two days in a condition consisting of 12–17% PEG 8000, 200 mM calcium acetate, 100 mM MES pH 6.0.

2.3. X-ray data collection

The crystals were cryoprotected by transfer into a solution consisting of the reservoir solution diluted with 20%(v/v) glycerol (99.5% grade). X-ray data sets were recorded either at 100 K using an Oxford Cryostream 700 cryogenic system (Oxford Cryosystems, Oxford, England) or at room temperature using an HC1 humidity controller with a humidity level calculated from the composition of the mother liquor (Sanchez-Weatherby et al., 2009 ▸). Crystal sizes and data-collection parameters are summarized in Table 1 ▸. X-ray data collections were carried out on beamlines ID29 (De Sanctis et al., 2012 ▸), ID30B (McCarthy et al., 2018 ▸) and ID30A-3 (Theveneau et al., 2013 ▸) at the ESRF, which all have a Gaussian beam profile with an ellipsoid or circular shape. Data-collection statistics are reported in Tables 2 ▸, 3 ▸ and 4 ▸.

Table 1. Data-collection parameters.

| Crystal dimensions (µm) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Temperature (K) | x | y | z | Relative humidity level (%) | a, b, c (Å) | Beamline | Beam size (µm) | Energy (keV) | Initial flux (photons s−1) | Wedge (°) | Exposure time (s) |

| Cerulean | 100 | 92 | 194 | 106 | — | 51.1, 62.7, 70.3 | ID29 | 30 × 40 | 12.7 | 2.3 × 1011 | 90–290 | 40 |

| 293 | 170 | 230 | 170 | 99 | 51.9, 63.0, 71.3 | ID29 | 30 × 40 | 12.7 | 2.7 × 1010 | 90–290 | 40 | |

| Lysozyme | 100 | 75 | 93 | 75 | — | 77.6, 77.6, 37.1 | ID30B | 40 × 40 | 12.7 | 3.4 × 1010 | 12–102 | 18 |

| 293 | 218 | 379 | 202 | 98 | 79.2, 79.2, 38.1 | ID29 | 30 × 40 | 11.5 | 4.1 × 1010 | 0–100 | 20 | |

| AtPhot2LOV2 (dark state) | 100 | 50 | 50 | 50 | — | 40.1, 40.1, 131.5 | ID30A-3 | 15 × 15 | 12.8 | 3.5 × 1011 | 0–107 | 43 |

| 293 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 98 | 40.9, 40.9, 132.7 | ID30A-3 | 15 × 15 | 12.8 | 1.4 × 1011 | 0–120 | 14 | |

| AtPhot2LOV2 (light state) | 100 | 75 | 76 | 82 | — | 40.3, 40.3, 131.3 | ID29 | 30 × 40 | 12.7 | 1.1 × 1010 | 87–177 | 36 |

| 293 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 98 | 41.5, 41.5, 133.5 | ID30A-3 | 15 × 15 | 12.8 | 2.0 × 1011 | 0–360 | 2.2 | |

Table 2. Data-collection and structure-refinement statistics for Cerulean.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| D1-100K | D2-100K | D3-100K | D4-100K | D5-100K | D6-100K | D7-100K | D8-100K | D9-100K | D10-100K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||||||||

| Temperature (K) | 100 | |||||||||

| Accumulated dose (MGy) | 0.29 | 0.58 | 0.87 | 1.16 | 1.45 | 1.74 | 2.03 | 2.32 | 2.61 | 2.9 |

| ESRF beamline | ID29 | |||||||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.976 | |||||||||

| Space group | P212121 | |||||||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 51.11, 62.72, 70.34 | 51.13, 62.74, 70.37 | 51.15, 62.67, 70.39 | 51.16, 62.78, 70.41 | 51.18, 62.80, 70.42 | 51.20, 62.82, 70.43 | 51.22, 62.84, 70.45 | 51.21, 62.82, 70.41 | 51.25, 62.87, 70.47 | 51.27, 62.88, 70.48 |

| Resolution range† (Å) | 46.82–1.46 (1.50–1.46) | 46.83–1.47 (1.51–1.47) | 46.84–1.48 (1.52–1.48) | 46.86–1.50 (1.54–1.50) | 46.87–1.52 (1.56–1.52) | 46.88–1.55 (1.59–1.55) | 46.89–1.57 (1.61–1.57) | 46.90–1.60 (1.64–1.60) | 46.91–1.63 (1.67–1.63) | 46.93–1.66 (1.70–1.66) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 28.345 | 28.876 | 29.474 | 30.075 | 30.696 | 31.433 | 32.101 | 32.736 | 33.41 | 33.874 |

| Unique reflections | 39910 (2939) | 39156 (2843) | 38421 (2778) | 36921 (2648) | 35579 (2618) | 3393 (2445) | 32406 (2390) | 30647 (2218) | 29061 (2114) | 27543 (2002) |

| Multiplicity | 7.1 (7.3) | 7.0 (7.3) | 7.0 (7.3) | 7.0 (7.2) | 7.0 (7.2) | 7.0 (7.1) | 7.0 (7.0) | 7.0 (6.7) | 7.0 (6.5) | 7.0 (7.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.9) | 99.9 (99.8) | 99.9 (99.9) | 99.8 (99.9) | 99.8 (99.9) | 99.8 (99.8) | 99.8 (99.7) | 99.8 (99.6) | 99.8 (99.3) | 99.9 (100.0) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 24.07 (1.56) | 24.42 (1.51) | 24.93 (1.45) | 25.52 (1.58) | 26.21 (1.56) | 27.72 (1.66) | 28.31 (1.73) | 29.55 (1.83) | 30.32 (1.82) | 31.42 (2.04) |

| R meas ‡ | 0.042 (1.387) | 0.041 (1.437) | 0.040 (1.478) | 0.040 (1.379) | 0.039 (1.370) | 0.038 (1.272) | 0.037 (1.216) | 0.036 (1.130) | 0.036 (1.144) | 0.036 (1.103) |

| CC1/2 | 0.999 (0.724) | 1.0 (0.697) | 1.0 (0.709) | 1.0 (0.750) | 1.0 (0.705) | 1.0 (0.703) | 1.0 (0.712) | 1.0 (0.728) | 1.0 (0.709) | 1.0 (0.717) |

| Refinement statistics | ||||||||||

| Resolution (Å) | 46.81–1.46 (1.50–1.46) | |||||||||

| R work | 0.167 (0.42) | |||||||||

| R free | 0.197 (0.38) | |||||||||

| No. of atoms | 2161 | |||||||||

| Average atomic B factor (Å2) | 23.47 | |||||||||

| R.m.s. deviations | ||||||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.012 | |||||||||

| Bond angles (°) | 1.63 | |||||||||

| PDB code | 6qq8 | |||||||||

| D11-100K | D12-100K | D13-100K | D14-100K | D15-100K | D16-100K | D17-100K | D18-100K | D19-100K | D20-100K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||||||||

| Temperature (K) | 100 | |||||||||

| Accumulated dose (MGy) | 3.19 | 3.48 | 3.77 | 4.06 | 4.35 | 4.64 | 4.93 | 5.22 | 5.51 | 5.80 |

| ESRF beamline | ID29 | |||||||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.976 | |||||||||

| Space group | P212121 | |||||||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 51.28, 62.90, 70.48 | 51.30, 62.91, 70.49 | 51.32, 62.93, 70.50 | 51.33, 62.94, 70.51 | 51.35, 62.96, 70.51 | 51.36, 62.97, 70.52 | 51.33, 62.94, 70.51 | 51.39, 62.99, 70.53 | 51.40, 63.00, 70.53 | 51.41, 63.00, 70.53 |

| Resolution range† (Å) | 46.93–1.68 (1.72–1.68) | 46.94–1.70 (1.74–1.70) | 46.95–1.72 (1.76–1.72) | 46.95–1.74 (1.79–1.74) | 46.97–1.76 (1.81–1.76) | 46.97–1.78 (1.83–1.78) | 46.96–1.79 (1.84–1.79) | 46.99–1.80 (1.85–1.80) | 46.99–1.81 (1.86–1.81) | 46.99–1.82 (1.87–1.82) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 34.4 | 34.9 | 35.4 | 35.8 | 36.2 | 36.6 | 37.1 | 37.6 | 38.2 | 38.7 |

| Unique reflections | 26603 (1935) | 25703 (1848) | 24856 (1814) | 24055 (1760) | 23260 (1697) | 22518 (1644) | 22113 (1613) | 21797 (1588) | 21457 (1562) | 21133 (1544) |

| Multiplicity | 7.0 (7.4) | 6.9 (7.4) | 6.9 (7.4) | 6.9 (7.4) | 6.8 (7.4) | 6.8 (7.4) | 6.8 (7.4) | 6.8 (7.4) | 6.8 (7.3) | 6.8 (7.3) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (100.0) | 99.9 (99.9) | 99.9 (99.9) | 99.9 (100.0) | 99.8 (99.9) | 99.9 (100.0) | 99.8 (100.0) | 99.8 (99.9) | 99.9 (100.0) | 99.9 (100.00) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 30.87 (2.09) | 31.11 (2.06) | 30.77 (2.20) | 31.25 (2.19) | 31.10 (2.24) | 31.16 (2.27) | 30.41 (2.17) | 29.48 (2.12) | 28.85 (2.08) | 28.23 (2.05) |

| R meas ‡ | 0.037 (1.079) | 0.037 (1.078) | 0.037 (1.068) | 0.037 (1.060) | 0.038 (1.030) | 0.038 (1.018) | 0.039 (1.066) | 0.040 (1.073) | 0.041 (1.072) | 0.042 (1.088) |

| CC1/2 | 1.0 (0.721) | 1.0 (0.760) | 1.0 (0.758) | 1.0 (0.745) | 1.0 (0.719) | 1.0 (0.775) | 1.0 (0.744) | 1.0 (0.767) | 1.0 (0.774) | 1.0 (0.726) |

| Refinement statistics | ||||||||||

| Resolution (Å) | 46.99–1.82 (1.87–1.82) | |||||||||

| R work | 0.154 (0.281) | |||||||||

| R free | 0.195 (0.345) | |||||||||

| No. of atoms | 2220 | |||||||||

| Average atomic B factor (Å2) | 33.9 | |||||||||

| R.m.s. deviations | ||||||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 | |||||||||

| Bond angles (°) | 1.38 | |||||||||

| PDB code | 6qq9 | |||||||||

| D1-293K | D2-293K | D3-293K | D4-293K | D5-293K | D6-293K | D7-293K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||||

| Temperature (K) | 293 | ||||||

| Accumulated dose (MGy) | 0.021 | 0.042 | 0.063 | 0.084 | 0.105 | 0.125 | 0.146 |

| ESRF beamline | ID29 | ||||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.976 | ||||||

| Space group | P212121 | ||||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 51.93, 63.04, 71.32 | 51.99, 62.91, 71.45 | 52.08, 62.94, 71.58 | 52.11, 62.91, 71.64 | 52.12, 62.87, 71.68 | 52.09, 62.77, 71.63 | 52.04, 62.67, 71.56 |

| Resolution range† (Å) | 47.24–1.66 (1.70–1.66) | 47.22–1.81 (1.86–1.81) | 47.27–1.95 (2.00–1.95) | 47.28–2.07 (2.12–2.07) | 47.27–2.18 (2.24–2.18) | 47.21–2.32 (2.38–2.32) | 47.15–2.45 (2.51–2.45) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 33.1 | 36.9 | 38.1 | 41.0 | 44.1 | 47.7 | 49.9 |

| Unique reflections | 28306 (2062) | 21964 (1592) | 17737 (1296) | 14881 (1060) | 12788 (912) | 10628 (773) | 9048 (670) |

| Multiplicity | 7.3 (7.4) | 7.3 (7.4) | 7.1 (7.1) | 7.1 (6.8) | 7.0 (7.7) | 6.8 (7.6) | 6.6 (7.4) |

| Completeness (%) | 100.0 (100.0) | 100.0 (99.9) | 99.9 (100.0) | 99.9 (99.6) | 100.0 (100.0) | 99.9 (100.0) | 99.9 (100.00) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 15.43 (2.09) | 21.87 (2.13) | 12.01 (2.06) | 10.65 (2.06) | 9.71 (2.03) | 9.65 (2.09) | 8.90 (2.08) |

| R meas ‡ | 0.07 (1.053) | 0.06 (1.190) | 0.132 (1.534) | 0.155 (1.501) | 0.168 (1.610) | 0.174 (1.562) | 0.185 (1.425) |

| CC1/2 | 0.998 (0.753) | 1.00 (0.788) | 0.998 (0.731) | 0.997 (0.641) | 0.997 (0.774) | 0.997 (0.815) | 0.997 (0.749) |

| Refinement statistics | |||||||

| Resolution (Å) | 47.23–1.66 (1.70–1.66) | 47.15–2.45 (2.51–2.45) | |||||

| R work | 0.144 (0.254) | 0.256 (0.386) | |||||

| R free | 0.171 (0.285) | 0.281 (0.417) | |||||

| No. of atoms | 2161 | 2161 | |||||

| Average atomic B factor (Å2) | 31.3 | 50.3 | |||||

| R.m.s. deviations | |||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.01 | 0.006 | |||||

| Bond angles (°) | 1.65 | 1.31 | |||||

| PDB entry | 6qqa | 6qqb | |||||

The resolution cutoff is based on CC1/2.

R meas = R merge × [N/(N − 1)]1/2, where N is the data multiplicity.

Table 3. Data-collection and structure-refinement statistics for HEWL.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| D1-100K | D2-100K | D3-100K | D4-100K | D5-100K | D6-100K | D7-100K | D8-100K | D9-100K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||||||

| Temperature (K) | 100 | ||||||||

| Accumulated dose (MGy) | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0.60 | 1.05 | 1.87 | 3.12 | 5.35 | 10.01 |

| ESRF beamline | ID29 | ||||||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.976 | ||||||||

| Space group | P43212 | ||||||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 77.56, 77.56, 37.13 | 77.56, 77.56, 37.14 | 77.58, 77.58, 37.15 | 77.60, 77.60, 37.16 | 77.64 77.64, 37.18 | 77.69, 77.69, 37.21 | 77.77, 77.77, 37.25 | 77.87, 77.87, 37.31 | 77.96, 77.96, 37.38 |

| Resolution range† (Å) | 33.49–1.42 (1.46–1.42) | 33.50–1.43 (1.47–1.43) | 33.51–1.43 (1.47–1.43) | 33.52–1.44 (1.48–1.44) | 33.54–1.49 (1.53–1.49) | 33.56–1.52 (1.56–1.52) | 33.60–1.58 (1.62–1.58) | 33.65–1.72 (1.76–1.72) | 33.71–1.92 (1.97–1.92) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 23.1 | 23.3 | 23.5 | 23.9 | 25.0 | 26.7 | 28.1 | 32.0 | 38.7 |

| Unique reflections | 20446 (1472) | 20032 (1407) | 20027 (1419) | 19659 (1405) | 17827 (1291) | 16874 (1242) | 15081 (1124) | 11760 (893) | 8490 (640) |

| Multiplicity | 6.5 (6.8) | 6.5 (6.8) | 6.5 (6.8) | 6.5 (6.9) | 6.5 (6.7) | 6.5 (6.6) | 6.5 (6.1) | 6.5 (6.4) | 6.4 (6.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 93.1 (92.5) | 93.2 (91.8) | 93.1 (92.0) | 93.1 (92.1) | 93.2 (94.2) | 93.3 (94.1) | 93.1 (94.6) | 92.6 (96.3) | 91.8 (95.7) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 17.49 (1.99) | 17.28 (2.03) | 17.51 (1.96) | 17.07 (1.96) | 17.87 (2.12) | 17.48 (1.96) | 17.15 (1.86) | 16.93 (1.98) | 15.34 (1.88) |

| R meas ‡ | 0.059 (0.836) | 0.060 (0.816) | 0.059 (0.842) | 0.060 (0.837) | 0.058 (0.791) | 0.059 (0.835) | 0.062 (0.909) | 0.065 (0.878) | 0.078 (1.015) |

| CC1/2 | 1.000 (0.703) | 0.999 (0.726) | 1.000 (0.710) | 1.000 (0.726) | 1.000 (0.724) | 1.000 (0.713) | 0.999 (0.718) | 0.999 (0.711) | 0.999 (0.706) |

| Refinement statistics | |||||||||

| Resolution (Å) | 33.49–1.42 (1.46–1.42) | 33.71–1.92 (19.7–1.92) | |||||||

| R work | 0.169 (0.262) | 0.156 (0.258) | |||||||

| R free | 0.203 (0.288) | 0.216 (0.267) | |||||||

| No. of atoms | 1212 | 1217 | |||||||

| Average atomic B factor (Å2) | 22.3 | 40.9 | |||||||

| R.m.s. deviations | |||||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.011 | 0.009 | |||||||

| Bond angles (°) | 1.78 | 1.572 | |||||||

| PDB code | 6qqc | 6qqd | |||||||

| D1-293K | D2-293K | D3-293K | D4-293K | D5-293K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||

| Temperature (K) | 293 | ||||

| Accumulated dose (MGy) | 0.020 | 0.040 | 0.060 | 0.080 | 0.100 |

| ESRF beamline | ID29 | ||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.07 | ||||

| Space group | P43212 | ||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 79.24, 79.24, 38.06 | 79.15, 79.15, 38.10 | 79.07, 79.07, 38.12 | 78.88, 78.88, 38.09 | 79.01, 79.01, 38.18 |

| Resolution range† (Å) | 39.62–1.37 (1.41–1.37) | 39.58–1.49 (1.53–1.49) | 39.54–1.59 (1.63–1.59) | 39.44–1.80 (1.85–1.80) | 39.51–1.95 (2.00–1.95) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 25.0 | 28.0 | 30.7 | 33.7 | 34.7 |

| Unique reflections | 25762 (1828) | 20176 (1450) | 16682 (1201) | 11545 (813) | 9218 (665) |

| Multiplicity | 7.0 (7.0) | 7.0 (7.3) | 7.0 (7.2) | 6.6 (7.1) | 6.7 (7.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.9 (96.9) | 99.2 (97.8) | 99.4 (99.8) | 99.3 (98.1) | 99.6 (99.7) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 17.10 (2.24) | 16.75 (2.43) | 15.84 (2.31) | 13.62 (2.54) | 10.45 (2.73) |

| R meas ‡ | 0.055 (0.810) | 0.059 (0.816) | 0.066 (0.863) | 0.108 (1.122) | 0.152 (1.138) |

| CC1/2 | 0.999 (0.70) | 0.999 (0.725) | 0.999 (0.715) | 0.998 (0.725) | 0.997 (0.708) |

| Refinement statistics | |||||

| Resolution (Å) | 39.61–1.37 (1.41–1.37) | 39.51–1.95 (2.00–1.95) | |||

| R work | 0.165 (0.271) | 0.167 (0.223) | |||

| R free | 0.195 (0.255) | 0.217 (0.230) | |||

| No. of atoms | 1221 | 1143 | |||

| Average atomic B factor (Å2) | 20.4 | 28.0 | |||

| R.m.s. deviations | |||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.05 | 0.009 | |||

| Bond angles (°) | 1.10 | 1.27 | |||

| PDB code | 6qqe | 6qqf | |||

The resolution cutoff is based on CC1/2.

R meas = R merge × [N/(N − 1)]1/2, where N is the data multiplicity.

Table 4. Data-collection and structure-refinement statistics for AtPhot2LOV2.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| Dark-100K | Light-100K D1 | Light-100K D2 | Light-100K D3 | Light-100K D4 | Light-100K D5 | Light-100K D6 | Light-100K D7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||||||

| Temperature (K) | 100 | 100 | ||||||

| Accumulated dose (MGy) | 2.68 | 0.024 | 0.048 | 0.071 | 0.095 | 0.119 | 0.143 | 0.167 |

| ESRF beamline | ID30A-3 | ID29 | ||||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.968 | 0.976 | ||||||

| Space group | P43212 | |||||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 40.15, 40.15, 131.57 | 40.32, 40.32, 131.28 | 40.33, 40.33, 131.28 | 40.32, 40.32, 131.28 | 40.38, 40.38, 131.40 | 40.38, 40.38, 131.41 | 40.38, 40.38, 131.41 | 40.38, 40.38, 131.41 |

| Resolution range† (Å) | 38.40–1.38 (1.43–1.38) | 38.55–1.70 (1.76–1.70) | 38.55–1.70 (1.76–1.70) | 38.55–1.70 (1.76–1.70) | 38.60–1.71 (1.77–1.71) | 38.60–1.71 (1.77–1.71) | 38.61–1.71 (1.77–1.71) | 38.61–1.71 (1.77–1.71) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 18.8 | 29.1 | 29.1 | 29.1 | 29.3 | 29.4 | 29.4 | 29.5 |

| Unique reflections | 23065 (2265) | 12655 (1202) | 12659 (1199) | 12667 (1207) | 12393 (1204) | 12383 (1201) | 12396 (1200) | 12382 (1197) |

| Multiplicity | 7.18 (6.32) | 6.24 (6.47) | 6.24 (6.45) | 6.24 (6.47) | 6.29 (6.45) | 6.29 (6.43) | 6.28 (6.43) | 6.29 (6.41) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (99.8) | 99.7 (99.0) | 99.8 (98.8) | 99.8 (99.4) | 98.4 (99.5) | 98.3 (99.1) | 98.4 (98.7) | 98.3 (98.4) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 16.84 (1.68) | 10.18 (1.74) | 10.39 (1.73) | 10.24 (1.71) | 11.46 (1.75) | 11.46 (1.78) | 11.34 (1.78) | 11.37 (1.67) |

| R meas ‡ | 0.061 (0.981) | 0.103 (0.826) | 0.101 (0.846) | 0.102 (0.830) | 0.096 (0.945) | 0.095 (0.933) | 0.096 (0.937) | 0.097 (0.980) |

| CC1/2 | 0.999 (0.568) | 0.997 (0.783) | 0.998 (0.791) | 0.998 (0.775) | 0.998 (0.804) | 0.996 (0.762) | 0.996 (0.782) | 0.998 (0.757) |

| Refinement statistics | ||||||||

| Resolution (Å) | 38.40–1.38 (1.42–1.38) | 38.55–1.70 (1.74–1.70) | 38.55–1.70 (1.74–1.70) | |||||

| R work | 0.140 (0.268) | 0.194 (0.289) | 0.190 (0.287) | |||||

| R free | 0.170 (0.288) | 0.239 (0.335) | 0.216 (0.391) | |||||

| No. of atoms | 1230 | 1208 | 1212 | |||||

| Average atomic B factor (Å2) | 16.6 | 23.5 | 23.7 | |||||

| R.m.s. deviations | ||||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.005 | |||||

| Bond angles (°) | 1.35 | 1.60 | 1.64 | |||||

| PDB code | 6qqh | 6qqi | 6qsa | |||||

| Light-100K D8 | Light-100K D9 | Light-100K D10 | Light-100K D11 | Light-100K D12 | Light-100K D13 | Light-100K D14 | Light-100K D15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||||||

| Temperature (K) | 100 | |||||||

| Accumulated dose (MGy) | 0.190 | 0.214 | 0.238 | 0.262 | 0.286 | 0.309 | 0.333 | 0.357 |

| ESRF beamline | ID29 | |||||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.976 | |||||||

| Space group | P43212 | |||||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 40.38, 40.38, 131.42 | 40.39, 40.39, 131.43 | 40.39, 40.39, 131.43 | 40.39, 40.39, 131.43 | 40.33, 40.33, 131.31 | 40.34, 40.34, 131.32 | 40.34, 40.34, 131.33 | 40.35, 40.35, 131.35 |

| Resolution range† (Å) | 38.61–1.71 (1.77–1.71) | 38.61–1.72 (1.78–1.72) | 38.61–1.71 (1.77–1.71) | 38.56–1.70 (1.76–1.70) | 38.56–1.71 (1.77–1.71) | 38.56–1.71 (1.77–1.71) | 38.56–1.71 (1.77–1.71) | 38.57–1.71 (1.77–1.71) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 29.5 | 29.4 | 29.6 | 29.4 | 29.5 | 29.4 | 29.5 | 29.5 |

| Unique reflections | 12371 (1186) | 12182 (1160) | 12390 (1205) | 12664 (1199) | 12453 (1188) | 12463 (1200) | 12467 (1204) | 12475 (1203) |

| Multiplicity | 6.29 (6.44) | 6.28 (6.39) | 6.29 (6.44) | 6.24 (6.46) | 6.23 (6.38) | 6.24 (6.40) | 6.23 (6.40) | 6.24 (6.45) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.2 (97.5) | 98.3 (99.1) | 98.3 (99.3) | 99.8 (99.2) | 99.8 (98.3) | 99.8 (99.3) | 99.8 (99.3) | 99.8 (99.3) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 11.37 (1.70) | 11.60 (1.77) | 11.18 (1.67) | 10.06 (1.66) | 10.27 (1.67) | 10.23 (1.68) | 10.12 (1.70) | 10.06 (1.65) |

| R meas ‡ | 0.096 (0.975) | 0.095 (0.937) | 0.098 (0.983) | 0.103 (0.879) | 0.101 (0.875) | 0.102 (0.855) | 0.103 (0.837) | 0.104 (0.875) |

| CC1/2 | 0.997 (0.741) | 0.998 (0.783) | 0.998 (0.760) | 0.997 (0.705) | 0.997 (0.727) | 0.996 (0.775) | 0.997 (0.758) | 0.997 (0.743) |

| Dark 293K | Light-293K D1 | Light-293K D2 | Light-293K D3 | Light-293K D4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||

| Temperature (K) | 293 | ||||

| Accumulated dose (MGy) | 0.354 | 0.034 | 0.068 | 0.102 | 0.136 |

| ESRF beamline | ID30A-3 | ||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.968 | ||||

| Space group | P43212 | ||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 40.886, 40.886, 132.691 | 41.45, 41.45, 133.53 | 41.45, 41.45, 133.53 | 41.45, 41.45, 133.53 | 41.45, 41.45, 133.53 |

| Resolution range† (Å) | 39.07–2.08 (2.15–2.08) | 39.59–2.40 (2.50–2.40) | 39.59–2.60 (2.70–2.60) | 39.59–2.76 (2.86–2.76) | 39.59–2.78 (2.88–2.78) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 43.1 | 52.0 | 59.6 | 63.0 | 67.7 |

| Unique reflections | 6924 (594) | 4926 (558) | 3897 (394) | 3275 (278) | 3217 (267) |

| Multiplicity | 8.56 (8.73) | 23.1 (23.5) | 23.1 (22.0) | 23.4 (21.1) | 23.4 (21.1) |

| Completeness (%) | 93.6 (87.4) | 98.0 (99.1) | 97.6 (99.0) | 97.4 (88.8) | 97.5 (86.4) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 10.72 (1.73) | 17.64 (1.52) | 19.14 (1.69) | 19.69 (2.47) | 17.12 (1.72) |

| R meas ‡ | 0.145 (1.169) | 0.177 (2.108) | 0.160 (1.749) | 0.154 (1.208) | 0.184 (1.639) |

| CC1/2 | 0.999 (0.501) | 0.999 (0.726) | 0.999 (0.727) | 0.999 (0.760) | 0.999 (0.712) |

| Refinement statistics | |||||

| Resolution (Å) | 24.21–2.08 (2.14–2.08) | 39.59–2.40 (2.46–2.40) | |||

| R work | 0.247 (0.348) | 0.239 (0.322) | |||

| R free | 0.292 (0.338) | 0.286 (0.314) | |||

| No. of atoms | 956 | 1043 | |||

| Average atomic B factor (Å2) | 38.7 | 46.9 | |||

| R.m.s. deviations | |||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.002 | 0.002 | |||

| Bond angles (°) | 1.24 | 1.47 | |||

| PDB code | 6qqj | 6qqk | |||

The resolution cutoff is based on CC1/2.

R meas = R merge × [N/(N − 1)]1/2, where N is the data multiplicity.

In order to perform the RT diffraction experiment on the unstable (in time, and potentially in dose) photoadduct of AtPhot2LOV2, we mounted a single crystal on the goniometer of beamline ID30A-3 at the ESRF under the air flux of an HC1 humidity controller and then illuminated it with a 470 nm blue LED for 10 min in order to populate the crystal with the covalent intermediate. Upon starting data collection (Table 4 ▸) the LED was turned off (a process triggered by the trigger of the beamline’s EIGER 4M detector) and 1650° of oscillation data (corresponding to four complete data sets) were collected in a contiguous manner in a total of 10 s. Diffraction images corresponding to each of the four data sets were then processed as described below.

2.4. Data reduction and structure refinement

The X-ray data sets were integrated, scaled and merged using the XDS program suite (Kabsch, 2010 ▸). Absorbed doses corresponding to the average dose of the exposed region were calculated using RADDOSE-3D (Zeldin et al., 2013 ▸). The 1.15 Å resolution structure of Cerulean (PDB entry 2wso; Lelimousin et al., 2009 ▸), the 1.2 Å resolution structure of lysozyme (PDB entry 5ebh; Zander et al., 2016 ▸) and the 1.7 Å resolution structure of AtPhot2LOV2 (PDB entry 4eep; Christie et al., 2012 ▸) were used as starting models for molecular replacement or refinement. Models were manually rebuilt and refined using Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▸) and REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 2011 ▸), respectively. In order to quantify the extent of specific damage from the crystallographic data, the default refinement protocol of REFMAC5 was modified by removing the restraint on B-factor continuity along covalent chains of atoms (Murshudov et al., 2011 ▸). Data-collection and refinement statistics are shown in Tables 2 ▸, 3 ▸ and 4 ▸. Structural coordinates and structure factors were deposited in the PDB (http://www.pdb.org/) with the following accession codes: 6qq8, 6qq9, 6qqa, 6qqb, 6qqc, 6qqd, 6qqe, 6qqf, 6qqh, 6qqi, 6qqj, 6qqk and 6qsa. The decay of the B 0/B n ratio as a function of dose was modelled with a monoexponential decay behaviour A + Bexp(−dose/τ), where τ is the life-dose or, when necessary, as a biexponential decay behaviour A + Bexp(−dose/τ1) + Cexp(−dose/τ2).

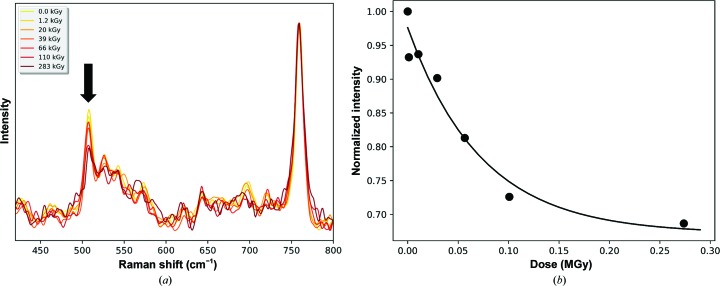

2.5. Online Raman spectroscopy

Online Raman spectroscopy was performed on beamline ID29 as previously described using a setup specifically designed for the collection of X-ray and Raman data in an interleaved manner (von Stetten et al., 2017 ▸). In brief, Raman spectra were recorded using an inVia Raman instrument (Renishaw, Wotton-under-Edge, Gloucestershire, England) equipped with a near-infrared (785 nm) 300 mW diode laser source. Raman spectra were measured from the X-ray-exposed region of a static lysozyme crystal with a composite acquisition time of 10 × 10 s for the 300–1800 cm−1 spectral window. Spectra were corrected for background using the WiRE software v.3.4 (Renishaw, Wotton-under-Edge, Gloucestershire, England). X-ray burn cycles were performed between Raman data sets by opening the shutter for increasing amounts of time, but no diffraction data were recorded. Absorbed doses were between 39 kGy and 1.21 MGy at 100 K and between 1.2 and 283 kGy at 293 K. The damage to disulfide bonds was evaluated by integrating the peak height of the 510 cm−1 band over the course of incremental dose absorption, the evolution of which with dose was modelled using a monoexponential decay behaviour A + Bexp(−dose/τ).

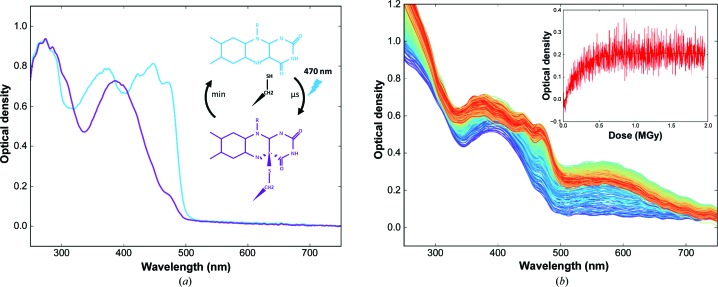

2.6. In crystallo UV–visible absorption spectroscopy of LOV2

Offline UV–Vis absorption spectra were recorded from an AtPhot2LOV2 crystal at room temperature on the ESRF ID29S Cryobench microspectrophotometer (von Stetten et al., 2015 ▸), using a high-sensitivity fixed-grating QE65Pro spectrophotometer with a back-thinned CCD detector (Ocean Optics, Dunedin, Florida, USA), a balanced deuterium–halogen DH2000-BAL light source (Ocean Optics, Dunedin, Florida, USA) and an HC1 humidity controller (Sanchez-Weatherby et al., 2009 ▸), before and after illumination with a 470 nm LED at 28 W cm−2. Spectra were averaged from ten 400 ms acquisitions from ∼50 µm thick crystals.

Online UV–Vis absorption spectra were recorded on beamline ID30A-3 at the ESRF using a dedicated microspectrophotometer (McGeehan et al., 2009 ▸) and were recorded using the same spectrophotometer and lamp from an AtPhot2LOV2 crystal illuminated for 5 min with a 470 nm LED at 0.7 W cm−2 before flash-cooling at 100 K and subsequent X-ray irradiation. Spectra were recorded at 5 Hz (200 ms acquisition time) from a ∼50 µm thick crystal maintained in a fixed position. Each spectrum recorded under X-ray irradiation corresponded to an absorbed dose of 14 kGy.

3. Results

3.1. Cerulean

Fluorescent proteins of the green fluorescent protein family are β-barrel-shaped proteins that contain a fluorescent chromophore formed by the autocatalytic cyclization of three consecutive amino-acid residues and, as such, they provide convenient genetically encoded fluorescent reporters of localization or interaction in cellulo (Tsien, 1998 ▸). Tuning the properties of fluorescent proteins (colour, brightness, pH sensitivity etc.) by mutagenesis has been facilitated by the availability of crystal structures of fluorescent proteins, all of which were determined at cryogenic temperature. Nevertheless, RT crystal structures have also become available based on diffraction data collected either at synchrotrons (Kaucikas et al., 2015 ▸) or at XFELs (Colletier et al., 2016 ▸; Coquelle et al., 2018 ▸; Hutchison et al., 2017 ▸). The sensitivity of fluorescent proteins to specific X-ray-induced radiation damage at cryogenic temperature has been well documented, showing that the conserved glutamate residue close to the chromophore (Glu222 according to the GFP sequence) appears to be specifically affected at relatively low absorbed doses [i.e. ∼0.1, 0.8 and 0.1 MGy for IrisFP (Adam et al., 2009 ▸), EGFP (Royant & Noirclerc-Savoye, 2011 ▸) and mNeonGreen (Clavel et al., 2016 ▸), respectively]. Given the sensitivity of this residue in fluorescent proteins to specific radiation damage, the cyan fluorescent protein Cerulean (Rizzo et al., 2004 ▸), which produces well diffracting crystals (Lelimousin et al., 2009 ▸; Gotthard et al., 2017 ▸), was chosen as the first target in the work described here.

3.1.1. Radiation damage to Cerulean at cryogenic temperature (100 K)

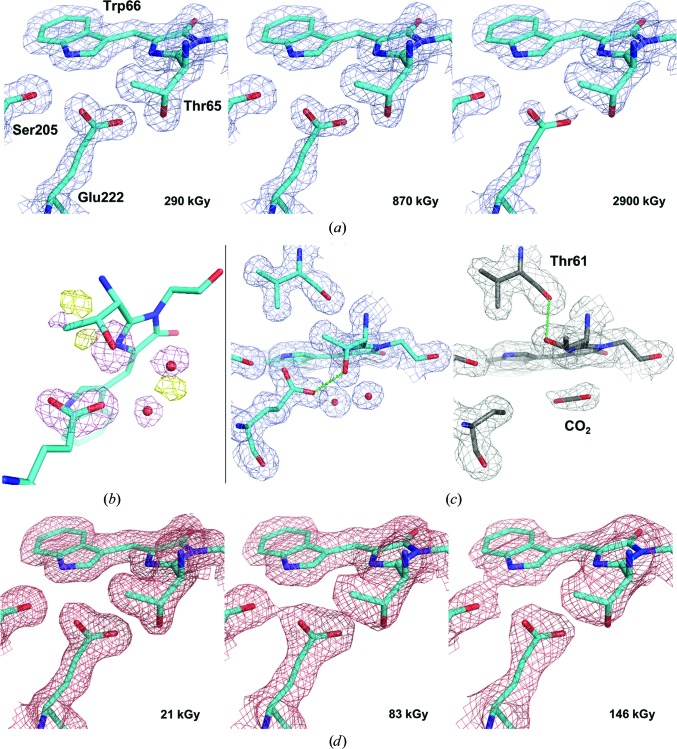

In order to investigate specific damage in crystals of Cerulean at 100 K, 20 consecutive data sets corresponding to accumulated doses of between 290 kGy and 5.8 MGy were recorded from the same position of a single crystal (Table 2 ▸). As expected from studies of other fluorescent proteins (Adam et al., 2009 ▸; Royant & Noirclerc-Savoye, 2011 ▸), Cerulean is sensitive to specific radiation damage at cryogenic temperatures and the progressive decarboxylation of Glu222 was observed in [2mF obs(i) − DF calc(i), αcalc(i)] electron-density maps [Fig. 1 ▸(a)] and in the [F obs(i) − F obs(1), αcalc(1)] Fourier difference map [Fig. 1 ▸(b)]. The progressive loss of this group results in rotation of the side chain of Thr65; the Oγ atom is originally engaged in a hydrogen bond to the carboxylate group of Glu222 [Fig. 1 ▸(c), left] and becomes engaged in a hydrogen bond to the carbonyl group of Thr61 [Fig. 1 ▸(c), right]. Two water molecules next to the Thr-Trp-Gly chromophore are also affected by the decarboxylation of Glu222, as shown by negative peaks in the [F obs(20) − F obs(1), αcalc(1)] map [Fig. 1 ▸(b)]. Examination of the [2mF obs(20) − DF calc(20), αcalc(20)] electron-density maps led us to replace these two water molecules by a linear carbon dioxide molecule, the obvious result of the photodecarboxylation process [Fig. 1 ▸(d)]. In order to compare the speed of global and specific radiation damage, we derived doses characteristic of each phenomenon from diffraction data and refined structure analysis.

Figure 1.

Evolution of the (2mF obs − DF calc, αcalc) electron-density map in data sets from a Cerulean crystal recorded at increasing absorbed doses at cryogenic and room temperature. (a) Series recorded at 100 K (maps contoured at a 1.5σ level). (b) [F obs(20) − F obs(1), αcalc(1)] Fourier difference map calculated between the final and the initial 100 K data sets, highlighting the specific radiation damage to Glu222 and its structural consequences (maps contoured at a ±5.0σ level). (c) (2mF obs − DF calc, αcalc) electron-density map for the first (left) and the last (right) 100 K data sets, illustrating the decarboxylation process of Glu222 and the rotation of Thr65 (maps contoured at a 1.0σ level). (d) Series recorded at 293 K (maps contoured at a 1.5σ level).

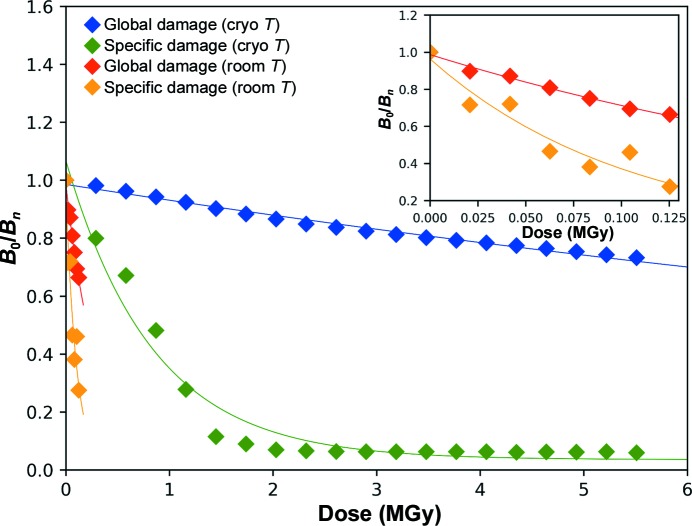

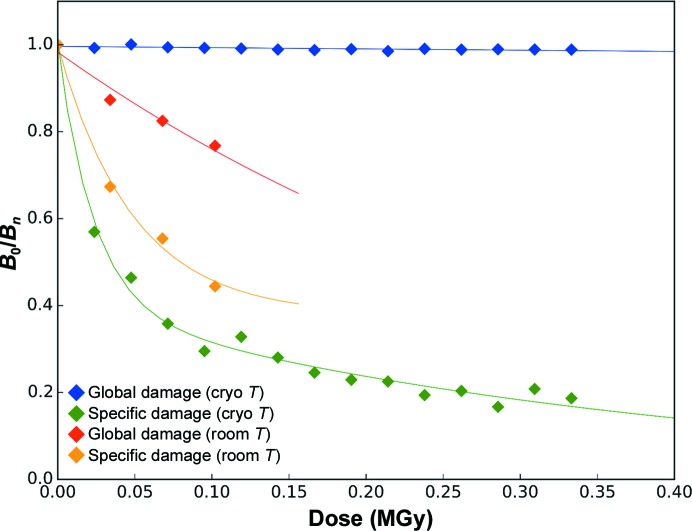

Diffraction resolution and B Wilson are common markers of global radiation damage (Ravelli & McSweeney, 2000 ▸). Indeed, at 100 K the resolution of the data sets progressively decreased from d min = 1.46 Å at an absorbed dose of 290 kGy to d min = 1.82 Å at an absorbed dose of 5800 kGy, which amounts to a decrease in the diffraction power of the crystal. Owen and coworkers derived a half-dose D 1/2 characteristic of global radiation damage by modelling a linear decay of the total diffracted intensities as a function of dose (Owen et al., 2006 ▸), which we also derived for our crystals (Table 5 ▸). In addition to this diffracted intensity-based metric, we derived a second dose constant from the evolution of B Wilson(n = 1)/B Wilson(n) that we modelled as a monoexponential decay (blue trace in Fig. 2 ▸). We obtained a B Wilson-derived life-dose τGlob-CT of 17.6 MGy (where CT stands for ‘cryogenic temperature’), which we chose as a metric of global radiation damage to Cerulean at 100 K. Both values (Table 5 ▸) are consistent with the Henderson and Garman absorbed dose limits (20 and 30 MGy, respectively) for crystals of biological macromolecules (Henderson, 1995 ▸; Owen et al., 2006 ▸).

Table 5. Global and specific radiation-damage dose constants.

| Protein | Cerulean | Lysozyme | AtPhot2LOV2 photoadduct | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (K) | 100 | 293 | 100 | 293 | 100 | 293 |

| D 1/2 (kGy) | 8790 | 134 | 9190 | 105 | 32700 | 169 |

| τGlob (kGy) | 17600 | 308 | 18200 | 251 | 34300 | 389 |

| τSpec (kGy) | 843 | 105 | 1475, 10500† | 198 | 22, 387† | 49 |

| ΔG/S | 20.8 | 2.9 | 12.4 | 1.3 | 1590 | 8.0 |

The specific damage curve for HEWL at 100 K is best fitted by two exponential decays, as observed previously (Carpentier et al., 2010 ▸), which suggests the existence of an X-ray-induced repair mechanism. The same is likely to apply to the specific damage to the covalent bond in the AtPhot2LOV2 photoadduct.

Figure 2.

Evolution of B factors as a function of dose for the irradiation series of Cerulean crystals at cryogenic and room temperature. The evolution of the Wilson B factor (blue, 100 K; red, 293 K) represents the global radiation damage and the evolution of the atomic B factor of Glu222 Cδ (green, 100 K; orange, 293 K) illustrates the specific radiation damage to the carboxylate group of Glu222. An enlargement of the low-dose range is presented in the inset.

To evaluate the characteristic dose at which specific radiation damage occurs at 100 K in crystals of Cerulean, we analysed the evolution of the atomic B factors of the progressively radiolysed carboxylate group of Glu222. Cδ is the only atom in the carboxylate group for which electron density eventually fully disappears [Fig. 1 ▸(a)]. All 20 structures were refined as if Glu222 had not been affected, with the smooth variation restraint on B factors of atoms implicated in consecutive covalent bonds (Murshudov et al., 2011 ▸) specifically removed. The evolution of B Glu222 Oδ(n = 1)/B Glu222 Oδ(n) was then modelled as a monoexponential decay, resulting in a life-dose for specific radiation damage in crystals of Cerulean at 100 K (τSpec-CT) of 843 kGy (green trace in Fig. 2 ▸).

The life-doses derived above indicate a strong decoupling between global and specific radiation damage in crystals of Cerulean at cryogenic temperature. In order to quantify this decoupling effect, we introduce the ratio between the global and the specific radiation-damage life-doses (ΔG/S-CT = τGlob-CT/τSpec-CT), which we estimated at 20.8 for Cerulean at cryogenic temperature. ΔG/S is thus the decoupling factor between global and specific radiation damage for a given protein at a given temperature. Life-doses and decoupling factors are summarized in Table 5 ▸.

3.1.2. Radiation damage to Cerulean at room temperature (293 K)

We performed a similar cumulative absorbed dose experiment on a Cerulean crystal maintained at room temperature during data collection [Table 2 ▸, Figs. 1 ▸(d) and 2 ▸]. We collected seven data sets with accumulated doses ranging between 21 and 146 kGy. As expected, there is a rapid drop-off in diffraction resolution (from d min = 1.66 Å for the first data set to d min = 2.45 Å for the last data set). The life-dose for global radiation damage at room temperature, τGlob-RT, was calculated to be 308 kGy (red trace in Fig. 2 ▸), which was 57 times lower than that observed at 100 K and was consistent with previous estimations concerning global radiation-damage rates at room and cryogenic temperatures (a decrease by a factor of between 26 and 113; Nave & Garman, 2005 ▸; Southworth-Davies et al., 2007 ▸). Intriguingly, however, (2mF obs − DF calc, αcalc) electron-density maps calculated from the successive cumulative dose data sets showed little, if any, sign of specific radiation damage [i.e. the decarboxylation of Glu222; Fig. 1 ▸(d)]. More surprisingly, calculation of successive [F obs(n) − F obs(1), αcalc(1)] Fourier difference maps did not show a build-up of strong peaks with increasing values as is generally observed in the analysis of a cryogenic radiation-damage data-set series. This prevented us from comparing the rate of specific damage at both temperatures using a Fourier difference map-based approach (Carpentier et al., 2010 ▸; Bury & Garman, 2018 ▸). Based on the evolution of the normalized atomic B factors of the atoms comprising the carboxyl group of Glu222, we derived the radiation-damage life-dose for this moiety at room temperature (τSpec-RT; orange trace in Fig. 2 ▸) to be 105 kGy, a value relatively close to that for the global damage. This leads to a decoupling factor of ΔG/S-RT = 2.9 for Cerulean at room temperature, which represents a sevenfold reduction of the radiation-damage decoupling between cryogenic and room temperatures. This observation is consistent with the lack of obvious visible evidence of specific radiation damage in crystals of Cerulean at room temperature. To investigate whether this observation is an isolated phenomenon, similar experiments were carried out on crystals of hen egg-white lysozyme, an archetypal radiation-damage test case.

3.2. Hen egg-white lysozyme

Hen egg-white lysozyme (HEWL) is one of the first proteins in which specific radiation damage was identified (Weik et al., 2000 ▸; Ravelli & McSweeney, 2000 ▸). The most prominent damage occurs to its four disulfide bonds, which lengthen owing to the formation of an anionic radical and eventually break (Weik et al., 2002 ▸; Sutton et al., 2013 ▸). Raman spectroscopy provides an X-ray-independent metric of damage to the disulfide bonds through monitoring of the Raman S—S stretching mode at 510 cm−1 (Carpentier et al., 2010 ▸). The bi-exponential evolution of its decay revealed the presence of an X-ray-induced repair mechanism, in which the anionic radical can revert back to the oxidized state upon further irradiation.

3.2.1. Radiation damage to hen egg-white lysozyme at cryogenic temperature (100 K)

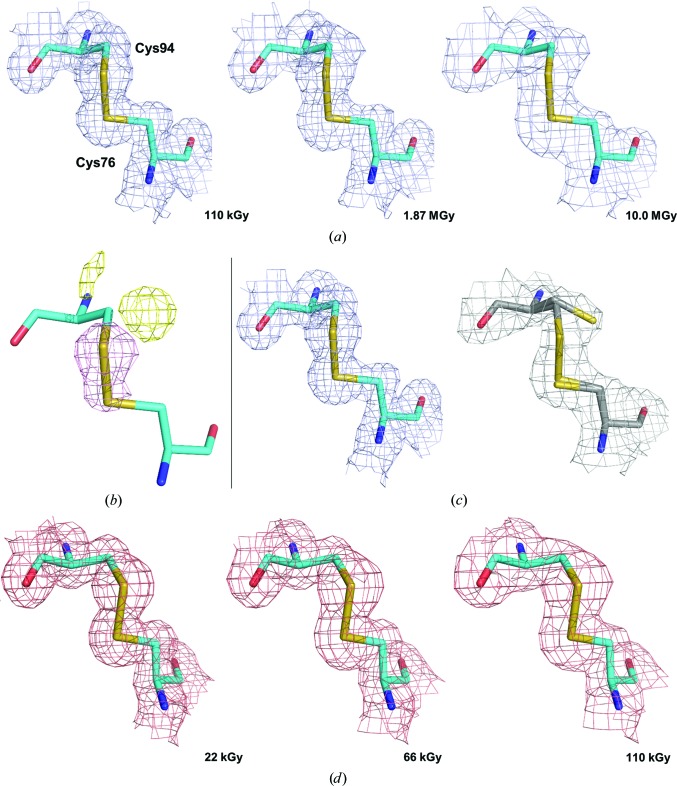

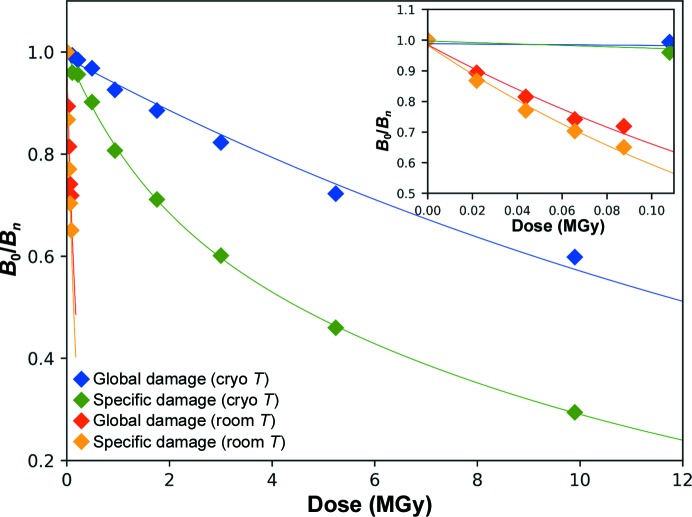

Using the same approach as for Cerulean, nine consecutive data sets, corresponding to accumulated absorbed doses of between 110 kGy and 10.0 MGy, were collected at 100 K from the same position of a single crystal. Over the nine data sets collected, the resolution of the diffraction data decreased from d min = 1.42 Å for the first data set to d min = 1.92 Å for the last data set. Examination of the [2mF obs(i) − DF calc(i), αcalc(i)] maps showed the expected progressive reduction of disulfide bonds, in particular for the Cys76–Cys94 disulfide bridge [Fig. 3 ▸(a)]. Based on the evolution of the Wilson B factors, τGlob-CT was estimated to be 18.2 MGy (blue trace in Fig. 4 ▸), consistent with the Henderson and Garman dose limits.

Figure 3.

Specific radiation damage in crystals of HEWL. Evolution of the (2mF obs − DF calc, αcalc) electron-density map in data sets of lysozyme recorded with increasing doses at cryogenic and room temperature. (a) Series recorded at 100 K (maps contoured at a 0.6σ level). (b) [F obs(6) − F obs(1), αcalc(1)] Fourier difference map calculated between the final and the initial data sets recorded at 100 K, highlighting the specific radiation damage to the disulfide bond Cys76–Cys94 (map contoured at a ±4.0σ level). (c) (2mF obs − DF calc, αcalc) electron-density map for the first (left) and the last (right) data sets recorded at 100 K, illustrating the breakage of the disulfide bond leading to the reorientation of the side chain of Cys94 (maps contoured at a 1.0σ level). (d) Series recorded at 293 K (maps contoured at a 1.0σ level).

Figure 4.

Evolution of B factors as a function of dose for the irradiation series of HEWL crystals at cryogenic and room temperature. The evolution of the Wilson B factor (blue, 100 K; red, 293 K) illustrates the global radiation damage and the evolution of the atomic B factor of Cys94 Sγ (green, 100 K; orange, 293 K) illustrates the specific radiation damage to the disulfide bond Cys76–Cys94. An enlargement of the low-dose range is presented in the inset.

In order to calculate the life-dose of specific radiation damage at 100 K, we concentrated on the disulfide bond between Cys76 and Cys94, as its reduction leads to the largest observable structural change, which is the reorientation of the side chain of Cys94 upon breakage of the disulfide bond [Figs. 3 ▸(b) and 3 ▸(c)]. The evolution of the normalized atomic B factor of Sγ of Cys94 is, as expected (Carpentier et al., 2010 ▸), best modelled by a bi-exponential decay, with a fast specific radiation-damage life-dose constant (τSpec-CT) of 1.48 MGy and a slow one (τ′Spec-CT) of 10.5 MGy (green trace in Fig. 4 ▸). Thus, as observed for Cerulean, there is a clear decoupling between specific and global radiation damage in crystals of lysozyme at 100 K (ΔG/S-CT = 12.4).

3.2.2. Radiation damage to hen egg-white lysozyme at room temperature (293 K)

To investigate radiation damage in crystals of HEWL at room temperature, five consecutive data sets corresponding to accumulated absorbed doses of between 22 and 110 kGy were collected from the same position of a single crystal (Table 3 ▸). Over the course of the five data sets collected, the resolution of the diffraction data decreased from d min = 1.37 Å for the first data set to d min = 1.89 Å for the last data set, and we derived a life-dose constant for global radiation damage at room temperature (τGlob-RT) of 251 kGy (red trace in Fig. 4 ▸), which is approximately 73 times lower than that seen in our experiment at 100 K, and is again consistent with the 26–113 range of increase (Nave & Garman, 2005 ▸; Southworth-Davies et al., 2007 ▸). However, the careful inspection of electron-density maps calculated for each of the five successive data sets showed no obvious sign of specific radiation damage to the Cys76–Cys94 disulfide bond [Fig. 3 ▸(d)], in accordance with previous observations (Southworth-Davies et al., 2007 ▸; Russi et al., 2017 ▸). Indeed, the evolution of the atomic B factor of Sγ of Cys94 can be best modelled with a life-dose τSpec-RT of 198 kGy (orange trace in Fig. 4 ▸), which gives a decoupling factor ΔG/S-RT for lysozyme at room temperature of only 1.3, which constitutes an almost perfect concurrency between the two types of radiation damage.

3.2.3. Spectroscopic investigations of specific radiation damage to hen egg-white lysozyme

We were intrigued by the apparent absence of specific radiation damage in our room-temperature diffraction-based investigations of both Cerulean and HEWL. To further investigate this, a diffraction-independent method, Raman spectroscopy, was used to investigate the photoreduction of disulfide bonds in crystals of HEWL at room temperature by monitoring the Raman peak at 510 cm−1, which is assigned to disulfide bonds (Carpentier et al., 2010 ▸).

Online in crystallo nonresonant Raman spectra were recorded on beamline ID29 (von Stetten et al., 2017 ▸) in an interleaved manner before and after X-ray burning cycles at room temperature (293 K). A decrease in the 510 cm−1 peak height is observed, demonstrating that specific radiation damage to disulfide bonds also occurs at 293 K [Figs. 5 ▸(a) and 5 ▸(b)]. Using the evolution of the 510 cm−1 peak height as a metric, the specific radiation-damage life-dose in crystals of HEWL at 293 K was calculated to be 89 kGy [Fig. 5 ▸(b)], which is of the same order as the life-dose derived from the diffraction-based experiments.

Figure 5.

Specific X-ray damage in hen egg-white lysozyme probed by Raman spectroscopy. (a) Evolution of Raman spectra recorded with increasing X-ray doses from a lysozyme crystal at 293 K. The arrow indicates the only band whose intensity decreases with increasing dose. (b) Decay of the disulfide-bond stretching mode at 510 cm−1.

3.3. Photoadduct of the LOV2 domain from A. thaliana phototropin 2

Light-, oxygen- or voltage-sensing (LOV) domains are protein modules that are found in higher plants, unicellular algae, fungi and bacteria that allow the sensing of environmental conditions (Christie et al., 2015 ▸). In particular, they are found in the blue-light photoreceptor phototropin used by higher plants to mediate positive or negative growth towards or away from a light source. LOV domains contain a light-sensing chromophore, the flavin FMN, which forms a covalent adduct with a cysteine upon absorption of a blue light photon, while exhibiting a blue shift of its absorption maximum [Fig. 6 ▸(a)]. The crystal structures of various LOV-domain photoadducts have been determined both at room temperature under photostationary illumination (LOV2 domain of the chimeric phytochrome/phototropin phy3 from Adiantum capillus-veneris; Crosson & Moffat, 2002 ▸) and at cryogenic temperature (LOV1 domain of phototropin 1 from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii; Fedorov et al., 2003 ▸). In the latter case, the radiosensitivity of the photoadduct required a composite data-set approach (i.e. the merging of partial data sets from several crystals). In the former, continuous illumination ensured a maximal population of the photoadduct in the crystal.

Figure 6.

Spectroscopic characterization of the dark and light states of AtPhot2LOV2. (a) Absorption spectra of the dark state (blue) and the blue-light-induced photoadduct (purple) recorded from crystals at room temperature. (b) Evolution of UV–Vis absorption spectra recorded with increasing X-ray doses from an AtPhot2LOV2 crystal at 100 K (inset: dose-dependent evolution of the absorbance at 490 nm, illustrating the X-ray-induced relaxation to the dark state).

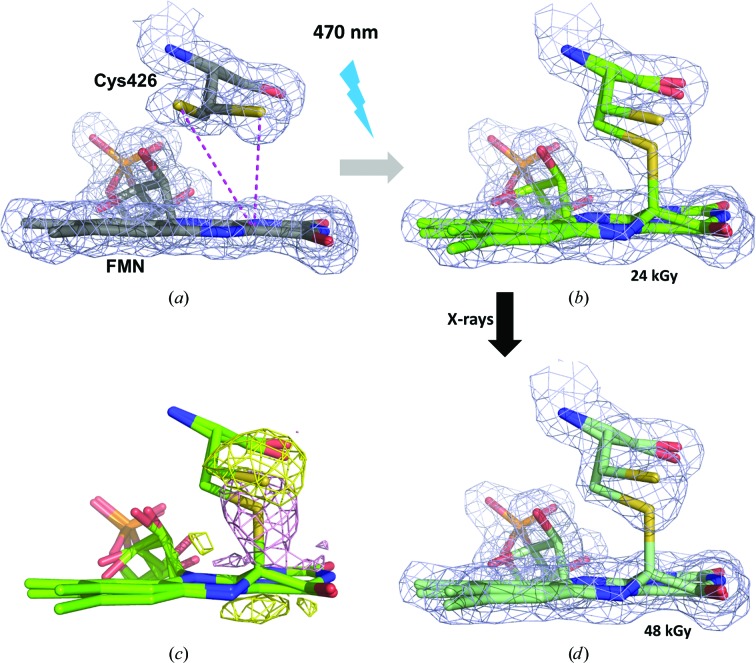

3.3.1. High X-ray sensitivity of the AtPhot2LOV2 photoadduct at 100 K

We chose the LOV2 domain of phototropin 2 from A. thaliana (AtPhot2LOV2) and investigated the global and specific radiation-damage sensitivity of its photoadduct. We first determined the crystal structure of AtPhot2LOV2 in its dark state at 1.38 Å resolution at cryogenic temperature. As can be seen in Fig. 7 ▸(a), the Sγ atom of the cysteine residue involved in photoadduct formation presents two alternate conformations: one in which the atom is at 3.6 Å from C4α (65% occupancy) and one in which the Sγ–C4α distance is 4.3 Å (35% occupancy) [Fig. 7 ▸(a)].

Figure 7.

(2mF obs − DF calc, αcalc) electron-density map in data sets for the dark and light states of AtPhot2LOV2 at 100 K. (a) Structure of the dark state at the position of the chromophore FMN (maps contoured at a 1.5σ level). (b) Structure of the light state recorded with an accumulated dose of 24 kGy (maps contoured at a 1.5σ level). (c) [F obs(2) − F obs(1), αcalc(1)] Fourier difference map calculated between the second and the first data sets of the irradiation series on the AtPhot2LOV2 light state, highlighting the very fast specific radiation damage to the Cys426–FMN covalent bond (map contoured at a ±4.0σ level). (d) Structure of the light state recorded with a total accumulated dose of 48 kGy (maps contoured at a 1.5σ level).

The photoadduct was generated in the crystal by illumination with a 470 nm LED just before flash-cooling. As for Cerulean and HEWL, we then collected 15 successive data sets from the same position of a single crystal, corresponding to accumulated absorbed doses of between 24 and 360 kGy, which constitutes a low-dose range (Table 4 ▸). Over the course of data-set collection, the diffraction limits hardly decreased from d min = 1.70 Å for the first data set to d min = 1.71 Å for the last data set, and we derived a life-dose τGlob-CT of 34.3 MGy (Fig. 8 ▸). As for the experiments described above for Cerulean and HEWL, this value is consistent with the Henderson and Garman limits.

Figure 8.

Evolution of B factors as a function of dose for the irradiation series of AtPhot2LOV2 crystals at cryogenic and room temperature. The evolution of the Wilson B factor (blue, 100 K; red, 293 K) illustrates global radiation damage and the evolution of the atomic B factor of Cys426 Sγ (green, 100 K; orange, 293 K) illustrates the specific radiation damage to the covalent bond Cys426–FMN that occurs concurrently with the time-dependent relaxation of the photoadduct.

Analysis of the crystal structure from the first data set (absorbed dose of 24 kGy) shows the presence of a mixture of the light-state structure with 50% occupancy (the presence of an Sγ—C4α covalent bond) and the dark-state structure with 50% occupancy [Fig. 7 ▸(b)], which results from the photostationary equilibrium obtained under continuous illumination before flash-cooling. The second data set (absorbed dose of 48 kGy) already shows significant photoreduction of the Sγ—C4α bond as shown by (2mF obs − DF calc, αcalc) electron-density maps and the Fourier difference map (F obs2 − F obs1, αcalc1) calculated between data sets 1 and 2 [Figs. 7 ▸(c) and 7 ▸(d)]. The Sγ atom of Cys426 implicated in the covalent adduct in the light-state structure was chosen to derive the specific radiation-damage life-dose τSpec-CT. The evolution of its B factor is best modelled by a bi-exponential decay, with a fast specific radiation-damage life-dose constant (τSpec-CT) of 22 kGy and a slow one (τ′Spec-CT) of 387 kGy. The resulting decoupling factor ΔG/S-CT of 1590 demonstrates that at 100 K this bond is two orders of magnitude more radiosensitive than the carboxylate group of Glu222 in Cerulean and the disulfide bond Cys94 in HEWL (Fig. 8 ▸).

In order to confirm these diffraction-based estimates, we used the complementary technique UV–Vis absorption microspectrophotometry (McGeehan et al., 2009 ▸) on beamline ID30A-3 (MASSIF-3) at the ESRF (Theveneau et al., 2013 ▸). Upon exposure to X-rays, the 390 nm peak characteristic of the light state changes into 450 and 470 nm peaks characteristic of the dark state [Fig. 6 ▸(b)]. This conversion can be interpreted as a result of X-ray-induced decay of the photoadduct species to the dark state [Fig. 7 ▸(a)]. We modelled the intensity increase of the 475 nm peak [inset in Fig. 6 ▸(b)] with the monoexponential behaviour A − Bexp(−dose/τ), which gives a life-dose of 207 kGy for the phenomenon. This value compares well with the fast and slow life-doses of 22 and 387 kGy, respectively, derived from the diffraction data.

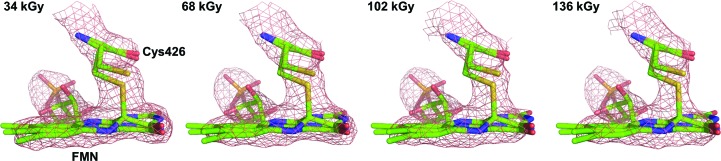

3.3.2. The AtPhot2LOV2 photoadduct at room temperature

While the AtPhot2LOV2 photoadduct builds up on the microsecond time scale, its decay back to the dark state occurs on the second to minute time scale (Kasahara et al., 2002 ▸), which opens up the possibility of determining its crystal structure at room temperature. We devised a strategy to record diffraction data as fast as possible in order to probe both global and specific radiation damage while minimizing the extent of intermediate-state relaxation. To this end, we used the EIGER 4M detector (Dectris, Switzerland) on beamline ID30A-3 (Theveneau et al., 2013 ▸) to record diffraction data from a crystal of AtPhot2LOV2 at RT immediately after blue-light irradiation. A continuous wedge of 1440° was recorded in 8.64 s, resulting in four successive 360° data sets, each of them for an absorbed dose of 34 kGy. Over the course of data collection, the resolution of the diffraction data as defined by the CC1/2 of the outer shell above 0.7 decreased from d min = 2.40 Å to d min = 2.78 Å. Representation of the four successive [2mF obs(i) − D F calc(i), αcalc(i)] maps at a 1.5σ level does not show a major disappearance of the electron density corresponding to the Sγ—C4α covalent bond (Fig. 9 ▸). Based on the evolution of B Wilson and of the atomic B factor of Cys426 Sγ, we calculate RT life-doses τGlob-RT and τSpec-RT of 389 and 49 kGy, respectively (Fig. 8 ▸). The resulting decoupling factor ΔG/S-RT of 8.0 constitutes a 200-fold reduction compared with the value at cryogenic temperature. Given that a significant part of the intermediate-state population has already relaxed even in 10 s, the ‘true’ value of ΔG/S-RT has to be closer to those observed for Cerulean (ΔG/S-RT = 2.9) and lysozyme (ΔG/S-RT = 1.3) (Table 5 ▸). This means that in all three of our cases the decoupling factor between global and radiation damage is less than 10 and is probably close to 1, posing the question of the severity of specific radiation damage at room temperature.

Figure 9.

Evolution of the (2mF obs − DF calc, αcalc) electron-density map (maps contoured at a 2.0σ level) in data sets for AtPhot2LOV2 recorded with increasing doses at room temperature.

4. Discussion

Our initial inability to detect traces of specific radiation damage in room-temperature diffraction data sets from single crystals of the fluorescent protein Cerulean prompted us to define a diffraction-based metric that would allow an easy comparison of the appearance of specific damage in different systems at various temperatures. To this end, the decoupling factor ΔG/S-T, which uses the onset of global damage for normalization at a given temperature T, was introduced. This ratio was calculated for both Cerulean and the well studied protein lysozyme at cryogenic and room temperature. At cryogenic temperature, the decoupling factors of 12 and 21, respectively, illustrate that the partial decarboxylation of a key glutamate residue in Cerulean and the partial reduction of a disulfide bond in lysozyme occur at moderate doses, well before the effects of global damage are apparent. At room temperature, however, the decoupling factors decrease to much lower values (1 and 3, respectively), suggesting a ‘recoupling’ of specific and global damage. In order to investigate whether this phenomenon also holds true for more radiosensitive systems, the same analysis was performed on the photoadduct of a phototropin LOV2 domain. Here, a huge decoupling factor of 1590 at cryogenic temperature reduces to a decoupling factor of only 8 at room temperature. In other words, and in contrast to the situation at cryogenic temperature, specific and global radiation damage evolve on similar dose scales at room temperature for these three systems, all of which involve covalent-bond breakage. Specific damage thus may appear to be as random as global damage, which would for instance explain why it does not show in Fourier difference maps.

Further studies, including simulations, are required to understand the mechanisms that cause the difference in behaviour at cryogenic versus room temperature. A potential reason may reside in the free-energy landscape offered at the respective temperatures to the solvated electrons and the free radicals that are generated by the interaction of X-rays with bulk-solvent molecules. Escape lanes for solvated electrons and free radicals terminate either on random groups, resulting in global damage, or on a few groups that are particularly reactive towards electrons and radicals, resulting in specific damage. The key difference between free radicals and solvated electrons is that the former are trapped, and therefore mostly inactive at cryogenic temperature, while the latter can still diffuse (Kmetko et al., 2011 ▸) and be funnelled towards electron-avid groups within the protein. At room temperature, however, all free radicals created in the bulk-solvent region can diffuse and impair crystalline order through various mechanisms such as the perturbation of crystalline contacts through direct damage to the protein or the generation of gas molecules (Garman, 2010 ▸). The recoupling of specific and global damage at room temperature suggests that the specificity of certain X-ray-induced damage to proteins may only arise at cryogenic temperature.

These results are of considerable interest for genuinely time-resolved protein crystallography, which is performed at room temperature (in contrast to methods relying on the cryo-trapping of intermediate states) and which requires the determination of the structures of particularly X-ray-sensitive intermediate states. Indeed, the structure determination of reaction-intermediate states trapped at cryogenic temperature has often required great care in minimizing, or controlling, the deposited dose (Berglund et al., 2002 ▸; Matsui et al., 2002 ▸; Adam et al., 2004 ▸; Bui et al., 2014 ▸). The ‘recoupling’ of specific and global radiation damage at room temperature will make specific damage much less of a problem, provided that a full data set can be recorded from a single crystal, which can be tested by monitoring parameters indicative of global damage, an option that is now readily accessible on synchrotron beamlines using software such as Dozor (Zander et al., 2015 ▸). An added advantage is that achieving the determination of a room-temperature structure of a given protein at a sufficiently high resolution will allow, by comparison, the identification of potential pitfalls in mechanism interpretation owing to specific radiation damage occurring in a cryogenic structure of the same protein. In summary, the development of easy-to-use humidity-controlled crystal environments and of fast and noise-free X-ray detectors is triggering a rebirth of room-temperature crystallography, which should be favoured in projects where obtaining a structure close to the structure in the physiological state is more important than reaching the highest resolution possible.

In conclusion, if one wishes to determine the structure of a protein whose active site (or another part) is particularly sensitive to X-rays, one can either work at cryogenic temperature and perform a thorough radiation-damage study by recording positive and negative control data sets aimed at closely monitoring the geometry of the active site (with the aim of deriving the maximum dose below which one should accumulate a complete data set) or work at room temperature and only focus on adjusting the X-ray flux to obtain a complete data set at the price of a reduced diffraction resolution.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: Cerulean, cryogenic temperature structure, accumulated dose 290 kGy, 6qq8

PDB reference: cryogenic temperature structure, accumulated dose 5.8 MGy, 6qq9

PDB reference: room-temperature structure, accumulated dose 21 kGy, 6qqa

PDB reference: room-temperature structure, accumulated dose 147 kGy, 6qqb

PDB reference: hen egg-white lysozyme, cryogenic temperature structure, accumulated dose 110 kGy, 6qqc

PDB reference: cryogenic temperature structure, accumulated dose 10 MGy, 6qqd

PDB reference: room-temperature structure, accumulated dose 20 kGy, 6qqe

PDB reference: room-temperature structure, accumulated dose 100 kGy, 6qqf

PDB reference: AtPhot2LOV2, ground state, cryogenic temperature structure, accumulated dose 2.68 MGy, 6qqh

PDB reference: blue light-irradiated, cryogenic temperature structure, accumulated dose 24 kGy, 6qqi

PDB reference: ground state, room-temperature structure, accumulated dose 384 kGy, 6qqj

PDB reference: blue light-irradiated, room-temperature structure, accumulated dose 34 kGy, 6qqk

PDB reference: blue light-irradiated, cryogenic temperature structure, accumulated dose 48 kGy, 6qsa

Acknowledgments

We thank Ulrike Kapp and Melissa Saidi for their help with the preparation of lysozyme crystals. The ESRF is acknowledged for access to beamlines and facilities for molecular biology via its in-house research programme. This work used the icOS Lab, which is a platform of the Grenoble Instruct Centre (ISBG; UMS 3518 CNRS–CEA–UJF–EMBL) with support from the French Infrastructure for Integrated Structural Biology (ANR-10-INSB-05-02) and GRAL (ANR-10-LABX-49-01) within the Grenoble Partnership for Structural Biology.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by European Synchrotron Radiation Facility grant .

References

- Adam, V., Carpentier, P., Violot, S., Lelimousin, M. L., Darnault, C., Nienhaus, G. U. & Bourgeois, D. (2009). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 18063–18065. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Adam, V., Royant, A., Nivière, V., Molina-Heredia, F. P. & Bourgeois, D. (2004). Structure, 12, 1729–1740. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Berglund, G. I., Carlsson, G. H., Smith, A. T., Szöke, H., Henriksen, A. & Hajdu, J. (2002). Nature (London), 417, 463–468. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Blake, C. C. F., Koenig, D. F., Mair, G. A., North, A. C. T., Phillips, D. C. & Sarma, V. R. (1965). Nature (London), 206, 757–761. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Borshchevskiy, V., Round, E., Erofeev, I., Weik, M., Ishchenko, A., Gushchin, I., Mishin, A., Willbold, D., Büldt, G. & Gordeliy, V. (2014). Acta Cryst. D70, 2675–2685. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bui, S., von Stetten, D., Jambrina, P. G., Prangé, T., Colloc’h, N., de Sanctis, D., Royant, A., Rosta, E. & Steiner, R. A. (2014). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 13710–13714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Burmeister, W. P. (2000). Acta Cryst. D56, 328–341. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bury, C. S. & Garman, E. F. (2018). J. Appl. Cryst. 51, 952–962.

- Carpentier, P., Royant, A., Weik, M. & Bourgeois, D. (2010). Structure, 18, 1410–1419. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Christie, J. M., Blackwood, L., Petersen, J. & Sullivan, S. (2015). Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 401–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Christie, J. M., Hitomi, K., Arvai, A. S., Hartfield, K. A., Mettlen, M., Pratt, A. J., Tainer, J. A. & Getzoff, E. D. (2012). J. Biol. Chem. 287, 22295–22304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Clavel, D., Gotthard, G., von Stetten, D., De Sanctis, D., Pasquier, H., Lambert, G. G., Shaner, N. C. & Royant, A. (2016). Acta Cryst. D72, 1298–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Colletier, J.-P., Sliwa, M., Gallat, F. X., Sugahara, M., Guillon, V., Schirò, G., Coquelle, N., Woodhouse, J., Roux, L., Gotthard, G., Royant, A., Uriarte, L. M., Ruckebusch, C., Joti, Y., Byrdin, M., Mizohata, E., Nango, E., Tanaka, T., Tono, K., Yabashi, M., Adam, V., Cammarata, M., Schlichting, I., Bourgeois, D. & Weik, M. (2016). J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 882–887. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Coquelle, N., Sliwa, M., Woodhouse, J., Schirò, G., Adam, V., Aquila, A., Barends, T. R. M., Boutet, S., Byrdin, M., Carbajo, S., De la Mora, E., Doak, R. B., Feliks, M., Fieschi, F., Foucar, L., Guillon, V., Hilpert, M., Hunter, M. S., Jakobs, S., Koglin, J. E., Kovacsova, G., Lane, T. J., Lévy, B., Liang, M., Nass, K., Ridard, J., Robinson, J. S., Roome, C. M., Ruckebusch, C., Seaberg, M., Thepaut, M., Cammarata, M., Demachy, I., Field, M., Shoeman, R. L., Bourgeois, D., Colletier, J.-P., Schlichting, I. & Weik, M. (2018). Nature Chem. 10, 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Crosson, S. & Moffat, K. (2002). Plant Cell, 14, 1067–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fedorov, R., Schlichting, I., Hartmann, E., Domratcheva, T., Fuhrmann, M. & Hegemann, P. (2003). Biophys. J. 84, 2474–2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fraser, J. S., van den Bedem, H., Samelson, A. J., Lang, P. T., Holton, J. M., Echols, N. & Alber, T. (2011). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 16247–16252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Garman, E. F. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 339–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Garman, E. F. & Schneider, T. R. (1997). J. Appl. Cryst. 30, 211–237.

- Gotthard, G., von Stetten, D., Clavel, D., Noirclerc-Savoye, M. & Royant, A. (2017). Biochemistry, 56, 6418–6422. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Henderson, R. (1995). Q. Rev. Biophys. 28, 171–193. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hope, H. (1990). Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 19, 107–126. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hutchison, C. D. M., Cordon-Preciado, V., Morgan, R. M. L., Nakane, T., Ferreira, J., Dorlhiac, G., Sanchez-Gonzalez, A., Johnson, A. S., Fitzpatrick, A., Fare, C., Marangos, J. P., Yoon, C. H., Hunter, M. S., Deponte, D. P., Boutet, S., Owada, S., Tanaka, R., Tono, K., Iwata, S. & Van Thor, J. J. (2017). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, E1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kasahara, M., Swartz, T. E., Olney, M. A., Onodera, A., Mochizuki, N., Fukuzawa, H., Asamizu, E., Tabata, S., Kanegae, H., Takano, M., Christie, J. M., Nagatani, A. & Briggs, W. R. (2002). Plant Physiol. 129, 762–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kaucikas, M., Fitzpatrick, A., Bryan, E., Struve, A., Henning, R., Kosheleva, I., Srajer, V., Groenhof, G. & Van Thor, J. J. (2015). Proteins, 83, 397–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kendrew, J. C., Dickerson, R. E., Strandberg, B. E., Hart, R. G., Davies, D. R., Phillips, D. C. & Shore, V. C. (1960). Nature (London), 185, 422–427. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kmetko, J., Warkentin, M., Englich, U. & Thorne, R. E. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 881–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Leal, R. M. F., Bourenkov, G., Russi, S. & Popov, A. N. (2013). J. Synchrotron Rad. 20, 14–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lelimousin, M., Noirclerc-Savoye, M., Lazareno-Saez, C., Paetzold, B., Le Vot, S., Chazal, R., Macheboeuf, P., Field, M. J., Bourgeois, D. & Royant, A. (2009). Biochemistry, 48, 10038–10046. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matsui, Y., Sakai, K., Murakami, M., Shiro, Y., Adachi, S.-I., Okumura, H. & Kouyama, T. (2002). J. Mol. Biol. 324, 469–481. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, A. A., Barrett, R., Beteva, A., Caserotto, H., Dobias, F., Felisaz, F., Giraud, T., Guijarro, M., Janocha, R., Khadrouche, A., Lentini, M., Leonard, G. A., Lopez Marrero, M., Malbet-Monaco, S., McSweeney, S., Nurizzo, D., Papp, G., Rossi, C., Sinoir, J., Sorez, C., Surr, J., Svensson, O., Zander, U., Cipriani, F., Theveneau, P. & Mueller-Dieckmann, C. (2018). J. Synchrotron Rad. 25, 1249–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McGeehan, J., Ravelli, R. B. G., Murray, J. W., Owen, R. L., Cipriani, F., McSweeney, S., Weik, M. & Garman, E. F. (2009). J. Synchrotron Rad. 16, 163–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Skubák, P., Lebedev, A. A., Pannu, N. S., Steiner, R. A., Nicholls, R. A., Winn, M. D., Long, F. & Vagin, A. A. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nave, C. & Garman, E. F. (2005). J. Synchrotron Rad. 12, 257–260. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Owen, R. L., Axford, D., Nettleship, J. E., Owens, R. J., Robinson, J. I., Morgan, A. W., Doré, A. S., Lebon, G., Tate, C. G., Fry, E. E., Ren, J., Stuart, D. I. & Evans, G. (2012). Acta Cryst. D68, 810–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Owen, R. L., Rudiño-Piñera, E. & Garman, E. F. (2006). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 4912–4917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Perutz, M. F., Rossmann, M. G., Cullis, A. F., Muirhead, H., Will, G. & North, A. C. T. (1960). Nature (London), 185, 416–422. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, C., Dworkowski, F. S. N., Wang, M. & Schulze-Briese, C. (2011). J. Synchrotron Rad. 18, 318–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ravelli, R. B. G. & McSweeney, S. M. (2000). Structure, 8, 315–328. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, M. A., Springer, G. H., Granada, B. & Piston, D. W. (2004). Nature Biotechnol. 22, 445–449. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Royant, A. & Noirclerc-Savoye, M. (2011). J. Struct. Biol. 174, 385–390. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Russi, S., González, A., Kenner, L. R., Keedy, D. A., Fraser, J. S. & van den Bedem, H. (2017). J. Synchrotron Rad. 24, 73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Weatherby, J., Bowler, M. W., Huet, J., Gobbo, A., Felisaz, F., Lavault, B., Moya, R., Kadlec, J., Ravelli, R. B. G. & Cipriani, F. (2009). Acta Cryst. D65, 1237–1246. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sanctis, D. de, Beteva, A., Caserotto, H., Dobias, F., Gabadinho, J., Giraud, T., Gobbo, A., Guijarro, M., Lentini, M., Lavault, B., Mairs, T., McSweeney, S., Petitdemange, S., Rey-Bakaikoa, V., Surr, J., Theveneau, P., Leonard, G. A. & Mueller-Dieckmann, C. (2012). J. Synchrotron Rad. 19, 455–461. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Southworth-Davies, R. J., Medina, M. A., Carmichael, I. & Garman, E. F. (2007). Structure, 15, 1531–1541. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Stetten, D. von, Giraud, T., Bui, S., Steiner, R. A., Fihman, F., de Sanctis, D. & Royant, A. (2017). J. Struct. Biol. 200, 124–127. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Stetten, D. von, Giraud, T., Carpentier, P., Sever, F., Terrien, M., Dobias, F., Juers, D. H., Flot, D., Mueller-Dieckmann, C., Leonard, G. A., de Sanctis, D. & Royant, A. (2015). Acta Cryst. D71, 15–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Studier, F. W. (2005). Protein Expr. Purif. 41, 207–234. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sutton, K. A., Black, P. J., Mercer, K. R., Garman, E. F., Owen, R. L., Snell, E. H. & Bernhard, W. A. (2013). Acta Cryst. D69, 2381–2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Theveneau, P., Baker, R., Barrett, R., Beteva, A., Bowler, M. W., Carpentier, P., Caserotto, H., Sanctis, D., Dobias, F., Flot, D., Guijarro, M., Giraud, T., Lentini, M., Leonard, G. A., Mattenet, M., McCarthy, A. A., McSweeney, S. M., Morawe, C., Nanao, M., Nurizzo, D., Ohlsson, S., Pernot, P., Popov, A. N., Round, A., Royant, A., Schmid, W., Snigirev, A., Surr, J. & Mueller-Dieckmann, C. (2013). J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 425, 012001.

- Tsien, R. Y. (1998). Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 509–544. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Warkentin, M., Badeau, R., Hopkins, J. B., Mulichak, A. M., Keefe, L. J. & Thorne, R. E. (2012). Acta Cryst. D68, 124–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Weik, M., Bergès, J., Raves, M. L., Gros, P., McSweeney, S., Silman, I., Sussman, J. L., Houée-Levin, C. & Ravelli, R. B. G. (2002). J. Synchrotron Rad. 9, 342–346. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Weik, M., Ravelli, R. B. G., Kryger, G., McSweeney, S., Raves, M. L., Harel, M., Gros, P., Silman, I., Kroon, J. & Sussman, J. L. (2000). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 623–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zander, U., Bourenkov, G., Popov, A. N., de Sanctis, D., Svensson, O., McCarthy, A. A., Round, E., Gordeliy, V., Mueller-Dieckmann, C. & Leonard, G. A. (2015). Acta Cryst. D71, 2328–2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zander, U., Hoffmann, G., Cornaciu, I., Marquette, J.-P., Papp, G., Landret, C., Seroul, G., Sinoir, J., Röwer, M., Felisaz, F., Rodriguez-Puente, S., Mariaule, V., Murphy, P., Mathieu, M., Cipriani, F. & Márquez, J. A. (2016). Acta Cryst. D72, 454–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zeldin, O. B., Gerstel, M. & Garman, E. F. (2013). J. Appl. Cryst. 46, 1225–1230.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials