Abstract

A woman experiences heightened vulnerability and faces tremendous challenges when transitioning to motherhood. This is exacerbated for young mothers and studies have shown that adolescent mothers experience an increased burden of responsibility during the transition to motherhood. Recent research addressing the experiences of adolescent mothers has increased. However, the current literature on this topic is still fragmented. The aim of this study was to conduct an integrative review of the literature to explore adolescent mothers' experiences of transition to motherhood and identify associated factors. The literature was searched using electronic databases: Medline, Cumulative index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), ProQuest, Scopus and PubMed. Relevant articles published in English from February 2005 to 2018 were included. Eighteen articles were included in the analysis. Based on this review, factors influencing a successful to transition to motherhood for adolescents included physical problems related to birth and breastfeeding, psychological well-being, ability to care for their baby, social support, education and economic strain and the provision of healthcare. The literature indicated a relationship between social supports and the development of positive maternal identity in the transition period for adolescent motherhood. Future healthcare interventions for adolescent mothers during the transitional period should aim to provide social support and the increase ability of adolescent mothers to manage the physical and psychological challenges of young motherhood, and enhance new mothers' knowledge about caring for babies.

Keywords: Adolescent, Motherhood, Role, Social support

1. Introduction

In recent decades, adolescent pregnancy has become an important health issue in many countries [1]. About 16 million girls aged 15–19 years and two million girls under the age of 15 years give birth every year [2]. Having babies during adolescence can have serious consequences for the health of the girl and her infant [3,4]. Adolescent bodies are not yet fully developed and too closely timed pregnancies, can result in girls who marry before the age of 18 years experiencing higher rates of life-threatening or debilitating conditions as a result of pregnancy [5]. The prevalence of other complications among adolescent mothers with severe maternal outcomes was found in one study to be 75% among mothers aged under 15 years and 47.8% among mothers aged 16–19 years. A high risk of stillbirth was found among all adolescent age groups, but the risk was significant only among adolescent mothers aged 16–17 years (AOR = 1.32; 95% CI, 1.11–1.57) [4] and there were increased rates of depressive symptoms in the postpartum period [6].

The transition to motherhood is a major development in a woman's life [7]. The transition begins during pregnancy and extends into the postpartum period. Settling-in process began as mothers began to feel competent and to develop confidence with their infants. Settling-in is usually achieved around four months following birth [7,8]. Transition to motherhood for teenage girls has been associated with many additional challenges compared with older new mothers [9]. These girls must manage multiple significant life changes at the same time, the shift to adulthood, a possible marriage, pregnancy, and motherhood [10].

A woman experiences heightened vulnerability and faces tremendous challenges when transitioning to motherhood [11]. This is exacerbated for young mothers and studies have shown that adolescent mothers experience an increased burden of responsibility during the transition to motherhood [12,13]. Adolescents often become mothers without the necessary knowledge, skills and resources to deal with early motherhood, which adds stress to their already challenged developmental level [14]. Thus, for effective adolescent motherhood transition support, an overview of the experiences of adolescent motherhood during pregnancy and childbirth and the factors associated with the transition to successful adolescent motherhood should be explored.

Recent research addressing the experiences of adolescent mothers has increased around the role of parental support [15], the influence of the father's involvement [16], joys and challenges of adolescent mothers [12,17], and health care experiences of adolescent mothers [18,19]. However, the current literature on this topic is still fragmented. The present review focused on identifying factors associated with the transition to motherhood for adolescent mothers. The knowledge gained from this study has importance in enabling healthcare professionals, as well as other professionals, dealing with pregnant teenagers to understand the key aspects of becoming and being a teenage mother, thus offering the teenage mothers they encounter optimum care. Thus, the aim of this paper was to identify associated factors during transition of adolescent mothers based on mothers' experiences.

2. Method

2.1. Literature search methods

An integrative approach is used to summarize previous research and to illustrate what is known about a particular phenomenon or health problem comprehensively and [20], in this case, the review focused on factors associated with a positive transition to adolescent motherhood. The literature was searched using electronic databases: Medline, Cumulative index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), ProQuest, Scopus and PubMed. Keywords were: 'motherhood* OR adolescent mother* OR adolescent motherhood* OR teenage mother* OR teenage motherhood* OR becoming a mother* OR motherhood transition* OR maternal identity*. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) written in English language between 2005 and 2018, (2) reported on mothers aged younger than 21 years old, (3) specific to transition to adolescent motherhood, and (4) original research. The search included adolescent motherhood during the transition period, which was defined as the period of pregnancy up to six months postpartum. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Unpublished research due to lack of formal peer-review, (2) reviews of literature or (3) articles reporting on assessment tool development.

2.2. Search outcomes

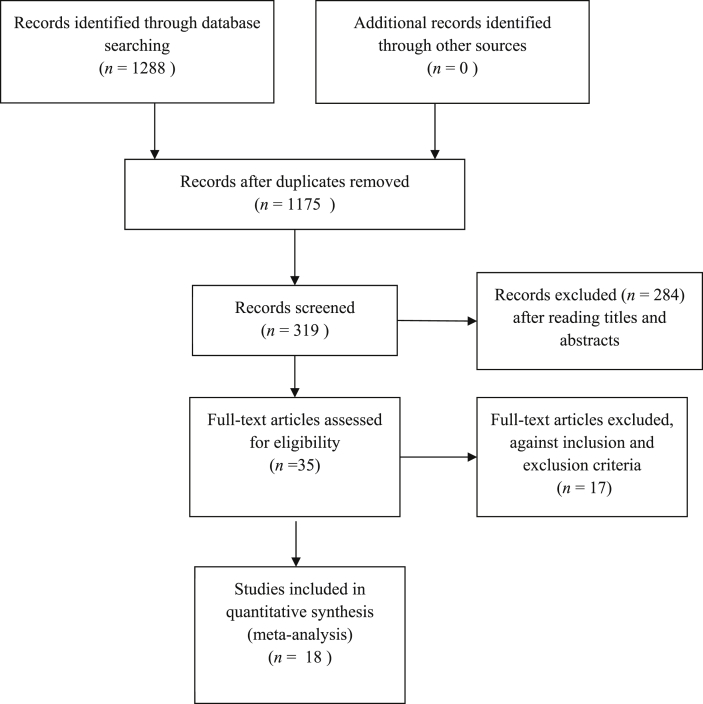

The search yielded 1288 titles related to adolescent motherhood (see details in Fig. 1). After duplicates were removed, 1175 manuscripts remained. Thirty-five papers remained after review of titles and abstracts, and these underwent full text review. Assessment of full texts excluded a further 17 papers leaving 18 papers for inclusion in this review.

Fig. 1.

The Flow chart describing details of literature search and selection strategy.

2.3. Data abstraction and quality assessment

The first author initially identified and reviewed citation on title and abstract. A second author independently reviewed and evaluated the papers selected for inclusion. We extracted the data related to author/s, year of publication, country, aim of the study, design and methods, sample and setting, key findings and evaluated the quality of the study (Table 1). Research studies which met the inclusion criteria were assessed for quality using the standard quality assessment criteria of Joanna Briggs Institute dependent on study design [21]. Quantitative studies were evaluated for the quality of: sample recruitment procedure, representativeness and sufficient sample size, inclusion criteria, connection between theoretical framework and hypothesis, instruments validity and reliability, ability to compare groups, suitable statistical data analysis, and generalizability of results. On the other hand, qualitative research studies were evaluated on: methodological congruency with the indicated philosophical view, study question, data collection procedures, data analysis methods, results interpretation, ethical consideration of study process and the basis of existing conclusion.

Table 1.

Details of studies in this review.

| Authors (Year) | Country | Aim of the study | Design and methods | Sample and settings | Key findings | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohammadi N et al. (2016) [9] | Iran | To explore the experience of pregnancy in Iranian teenage women | An interpretive phenomenological study In-depth interviews |

11 adolescent mothers aged 15–17 years Primary Health Care Centre |

|

High |

| Ngum Chi Watts M et al. (2015) [10] | Australia | To solicit lived experiences of African Australian young refugee women who had experienced early motherhood in Australia | Qualitative study In-depth interview |

16 African Australian teenagers who had refugee backgrounds Community setting |

|

|

| Mangeli M et al. (2017) [12] | Iran | To explore the challenges encountered by Iranian adolescent mothers during the transition to motherhood | Qualitative study In-depth interviews |

16 adolescent within ages of 14–18 at the time of childbirth Community setting |

|

High |

| Sheeran N et al. (2016) [13] | Australia | To explicate the experience of being a mother for adolescent women who experienced a preterm or term birth in Australia. | Interpretative phenomenological study Individual guided interview |

14 primiparous women aged 15–19 years Four hospitals (both regional and metropolitan) southeast Queensland |

|

High |

| Copeland R et al. (2017) [15] | Costa Rica | To gain a better understanding of the lived experiences of mothers, as well as the kinds of support they received during and after the pregnancy | Qualitative study Semi-structured interviews Case study |

22 women who had become pregnant in adolescence (before the age of 18 years) Primipara and multipara Community setting |

|

High |

| Malette J et al. (2015) [16] | USA | To explain the relationships between prenatal and post birth father involvement, inter-parental relationship quality, and maternal identity. | Cross-sectional study Questionnaire of prenatal father involvement Inter-parental relationship Quality Maternal identity |

125 mothers aged from 14 to 19 years School based program for adolescent parent from 32 schools in Ohio. |

|

Average |

| Sheeran N et al. (2015) [17] | Australia | To understanding of the daily experience of being a young mother for Australian young women who had preterm infants | Qualitative interpretive phenomenological Individual guided interview |

14 primiparous women aged 15–19 years Four hospitals (both regional and metropolitan) southeast Queensland |

|

High |

| Harrison ME et al. (2017) [18] | Canada | To share pregnant and parenting youths' experiences with health care to inform recommendations for promoting youth- friendly medical encounters | Qualitative descriptive study Focus group discussion |

26 mothers aged 19 years or younger 3 sites Pregnant and parenting youth in community |

|

High |

| Hunter L et al. (2015) [19] | UK | To explore how the inpatient experiences of a group of young women who gave birth as teenagers influenced their feeding decisions and experiences, and ascertain their ideals for breastfeeding support | Qualitative study Focus group discussion |

15 women aged 16–20 years Community setting in Oxfordshire |

|

High |

| Gyesaw N et al. (2013) [24] | Ghana | To explores the experiences of adolescent mothers during pregnancy, childbirth, and care of their newborns | Qualitative study In-depth interviews Focus group discussions |

54 teenage mothers aged 14–19 years Primipara Facility and community level |

|

High |

| Salusky I et al. (2013) [25] | Dominican Republic | To understand the experience of becoming a mother at an early age in a group of marginal young women | Qualitative study Semi-structured interviews |

21 young mothers who became pregnant before aged 18 years. Two areas located in community: Urban and isolated |

|

High |

| Wilson-Mitchell et al. (2014) [26] | Jamaica | To explore the experiences and impact of pregnancy on pregnant adolescents' psychological health | Mixed method Individual interview, focus group interviews |

30 pregnant adolescent 16 years and older Primipara Two hospital held a “Teen-centred” clinic and a standard antenatal clinic. |

|

High |

| Klingberg-Allvin et al. (2008) [27] | Vietnam | To explores married Vietnamese adolescents' perceptions and experiences related to transition into motherhood and their encounter with health care service | Qualitative study In-depth interviews |

22 women younger than 20 who were either pregnant or had newly delivered The Commune Health Centre (CHC) |

|

High |

| DeVito J. (2010) [28] | USA | To explore and better understand first-time adolescent mothers' meanings and experiences of parenting during the 4-to-6 week postpartum period | Qualitative study Individual interview with open-ended |

126 adolescent mothers Four postpartum clinical sites |

|

Average |

| Roberts S et al. (2011) [29] | Australia | To explore the lived experiences and social context prior to becoming pregnant, of women who became mothers during adolescence in rural Victoria | Qualitative interpretive phenomenological In-depth semi-structured interviews |

Four mothers aged between 16 and 20 years Rural North East Victoria |

|

Average |

| Wahn E et al.(2005) [30] | Sweden | To describe the perspectives, experiences, and reasoning about becoming and being a teenage mother by Swedish teenage girls. | Qualitative study Individual interview |

20 pregnant and parenting girl aged 15–19 years Urban, rural and suburban district |

|

High |

| Ngai FW et al. (2015) [35] | Hong Kong | To explore Chinese women's perceptions of maternal role competence and factors contributing to maternal role competence during early motherhood. | Exploratory descriptive study Semi-structured interviews |

26 mothers at six weeks postpartum aged 18 years or above Home visit |

|

High |

| DeVito J. (2007) [36] | USA | To investigate factors that may contribute to self-perceptions of parenting in adolescent mothers during the 4- to 6-week post-partum period | Descriptive correlational design The Norbeck social support Questionnaire (NSSQ) The what being the parent of a baby is like-revised instrument |

126 adolescent mothers under 20 years of age, 4–6 weeks postpartum Four sites in New Jersey |

|

High |

3. Results

A total studies reviewed of 18 studies included 15 qualitative studies, two quantitative studies, and one mixed methods study were included in the review. All articles addressed adolescent motherhood transition. Studies were conducted in a range of countries around the world: four studies were from Australia, three studies were conducted in United States of America, two studies were conducted in Iran, and there was one study each from Canada, United Kingdom, Sweden, Ghana, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, and Jamaica. All populations studied were adolescent mothers (aged 14–20 years) during pregnancy and childbirth period with sample sizes from 4 to 126. The study setting varied from clinical to community sites with studies taking place in urban, suburban and rural areas.

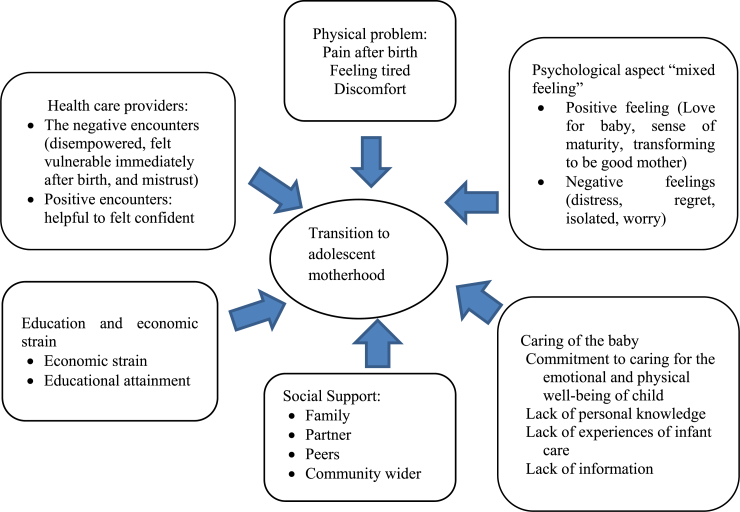

Key factors reported in these studies reported by teenage mothers transitioning to motherhood related to physical problems associated with pregnancy, birth and breastfeeding, as well as psychological impacts with “mixed feelings”, caring for the baby, heightened need for social support, education and economic strain and health care. A summary of these factors is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Factors that influence the motherhood transition of adolescent women.

3.1. Physical problems

Transition to becoming a mother is an important event in the life of a woman [22]. Most teenagers were not ready to become mothers and thus experienced multiple challenges [23]. Three studies reported that adolescent mothers experienced physical problems during childbirth [12,19,24]. Teenagers stated that the pain associated with labor in the postpartum period become an obstacle to caring for the baby [24]. Many young mothers felt incapacitated because of tiredness and pain after giving birth [19]. You mothers felt that this prevented them developing a deeper attachment with their newborn [19]. Hunter et al. reported that teenage mothers felt tired and helpless after giving birth and thus needed additional assistance from health workers after giving birth [19].

3.2. Psychological aspects - “mixed feelings”

The majority of studies have shown the effect of psychological aspects during transition of adolescent mothers. Young mothers articulated complex emotions during pregnancy and giving birth and expressed mixed feelings, including joy and worry, about their new responsibility [9,10,12,15,17,[25], [26], [27]].

Negative feelings to becoming mothers were expressed as feelings of loss and regret related to their past lives and perceived future opportunities. The young women regretted the loss of their adolescence, and loss of continuing education [15]. This feeling expressed by primiparous adolescent mothers. Two studies found that adolescent mothers felt isolated and alone [28,29]. Feeling isolated was a significant experience of participants' lives early in pregnancy. They felt different to their peers and were outcasts at school [29]. The same feeling was also reported by adolescent mothers after giving birth [29]. Many adolescent said their peers did not understand their conditions and the demands of meeting the needs of their babies, and thus felt a lack of support and loss of friendships with their peers [28].

Two studies reported psychological distress in adolescent primiparous mothers [12,26]. The mothers felt distress because of their perceived unpreparedness for pregnancy [29] and seven out of the 30 (23%) teenage mothers reportedly experienced depression, and 6,6% suicidal ideation or entertained thoughts of killing themselves [26]. These feelings occurred with mothers who had an unwanted pregnancy and difficulty in accepting the responsibilities of motherhood [12].

While several studies described young mothers negative feelings related to transition to motherhood, they also found most adolescent mothers revealed positive feelings associated with their transition [9,10,13,17, [30], [31], [32], [33]]. The majority of qualitative studies noted that adolescent mothers felt the transition as a life change into adulthood [29], they felt motherhood transition as a sense of maturity, and had positive self-perceptions when transforming to be good mothers [9,13,27,31]. In this context, adolescent mothers were generally happy to have their babies and felt their lives had changed for the better since becoming mothers [10]. Becoming a mother provided all the teenage mothers with the opportunity to develop. They described becoming more mature, less egocentric as they learned and grew to becoming good mothers [13,28,31]. To highlight the complexity, of new mothers feelings, one study found that despite the challenges, adolescent mothers predominantly felt unconditional love and positive feelings about their babies [25].

3.3. Caring for the baby

Many teenage mothers described that caring for their infants was the most challenging responsibility they had ever faced [34]. Three of the qualitative studies were concerned with mothers' care for their babies. The impeding factors maternal role competence included a lack of personal knowledge and experiences of infant care [12] and contradicting information from various sources [35]. However, Ngai et al. explored factors affecting maternal role competence, finding factors facilitating maternal role competence included positive experiences of infant care, well-being of the infant, success in breastfeeding and availability of social support. However, Similarly, Furthermore, one core essential characteristic of the competent mother is commitment towards caring for the emotional and physical wellbeing of the child [35].

3.4. Social support

One important aspect for adolescent mothers is social support. The most important sources of social support were found to be from their parents, especially the new mother's mother. Social support from their partner was the second most important type of support [10,16,23,24,29,33]. One cross-sectional study showed that father involvement pre and post birth was positively associated with adolescent mothers' maternal identity [16]. In line with another descriptive correlational study, social support from her mother and the baby's father were factors that may contribute to the development of positive self-perception of adolescent parenting [36] and they often needed assistance from their families to care for their babies [24].

Besides support from family, two qualitative studies reported support from friends and society was particularly needed by adolescent mothers [10,30]. Wahn et al. found that received support was experienced in varied ways, both positive and negative. Support from families, friends and society was seen to contribute to successful motherhood, but the support from the professional network was not always adapted to the adolescents' sometimes uncommunicated needs [30]. A study with African Australian adolescent mothers confirmed the need for some social support during the postpartum period to be available to assist them to meet challenges of early motherhood from family, friends, and the baby's father. However, none of the participants had received support for the baby from their community because of negative community perceptions of teen mothers that increased young women's risk of isolation [10].

3.5. Education and economic strain

Five studies described other challenges contributing to adolescent motherhood as economic strain and educational attainment [10,17,25,26,30]. Practical difficulties with housing, transport and financial strain significantly impacted on experiences of some young mothers [17,25,26]. Some adolescent mothers felt regret having a baby while still at school, when they unable to finish their education, this then led to difficulty finding work compounding financial stressors. Meeting the needs of the baby, continuing their education and making friends were very difficult for teen mothers [10]. One study revealed that having a newborn was seen my young mothers as their motivation to complete school, as they claimed they would continue their education in the future in order to provide the best future possible for their babies [36]. Despite this, Mitchel et al. found that most of the teenage mothers discontinued their education and policies had not yet been implemented to support new mothers in school. Indeed, in Africa the discovery of pregnancy sometimes led to expulsion from school [12,26].

3.6. Health care providers

Four studies explored whether healthcare providers in clinical settings supported the transition process of adolescent mothers [18,19,27,30]. One study found that young women often felt disempowered and vulnerable immediately after birth [19]. When health professionals took control in providing care to the infant rather than supporting the new mother to do this herself, there was a compounded feeling of helplessness experienced by young mothers [19]. Another study described variable experiences of adolescent mothers' healthcare. Negative experiences seemed more memorable and hurtful, demonstrating mothers' general sense of mistrust [18] and lacking power with regard to decisions in relation to pregnancy, delivery, and contraceptive usage [27]. However, positive attitudes and supportive open communication from midwives and social workers helped participants to feel more confident in becoming young mothers [30].

4. Discussion

This study reviewed existing literature on the transition experiences to adolescent motherhood to identified factors associated. We identified factors contributing to the transition to adolescent motherhood (both positive and negative) that included physical challenges associated with birth, pregnancy, breastfeeding and psychological aspects related to transiting to motherhood with “mixed feelings”, concerns around caring for the baby, the need social support, and supportive rather than controlling healthcare.

The transition to becoming a mother requires extensive psychological, social, and physical adaptation. A woman experiences heightened vulnerability and faces tremendous challenges as she makes this transition [11]. Mothers faced several health problems related to pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and breastfeeding [12,19,24]. Pain related to the birth process and feeling tired and experiencing pain after giving birth prevented new mothers from caring for their newborns [19].

The adolescent mothers simultaneously faced multiple developmental challenges related to transition into adulthood, marriage, pregnancy and mothering responsibilities [9,12]. Meleis et al. states that good physical and psychological well-being of mothers would positively influence the process of maternal transition [8]. Our review suggests that teenage mothers experienced some negative feelings associated with being a mother, mostly related to mourning for a life as it was with friends and school. However, feelings of love with their infants expressed by teenage mothers in studies in this review highlighted their enjoyment with the process of becoming mothers. When new mothers felt happiness as a mother they were more likely to demonstrate commitment to caring for their babies. However, this review did not compare primiarous and multipara mothers' related psychologic aspects.

The results of studies that explored maternal role during transition revealed caring for the baby was the most challenging mothering responsibility. The process of transition evaluated maternal competence in caring for their babies and comfort in going through the transition to becoming mothers and are important components and challenges in primary health care [37]. Adolescent mothers experienced lack of knowledge about infant care and contradictory information from various sources were obstacles to caring for their babies. However, essential characteristics of the competent mother included a commitment to care for the emotional and physical wellbeing of the infant, and availability of social support would facilitate competence in caring for the baby [35].

Social support is a well-meaning action that is given to someone with whom there is a personal relationship, and produces positive responses from the recipient [38]. Brown et al. described social support received by adolescent mothers in the first six months postpartum, suggesting that social support in the form of emotional, informational, tangible support and problem-solving support showed a positive impact during the early postpartum period [39]. Many studies indicated that social support positively influenced transition of adolescent mothers [10,15,26,30,36]. Young mothers believed social support increased their confidence in caring for their children [32]. Adolescent mothers not only needed to social support from their family, but also peers, the wider community and health services [10,26].

Previous research have shown that adolescent mothers were faced with extreme economic and social marginalization [25,30]. Some participants from studies within this review identified extreme financial hardship [25]. The meaning and experience of mothering was also framed by the level of stability in their daily life, particularly in terms of housing, income, and appropriate support [17]. Compounding their poverty, another issue related to adolescent motherhood in these studies was educational attainment [10,36]. Some young mothers had regrets in relation to having babies while still at school, and verbalized a desire to return to school. In some contexts this was not supported by school policy, and the discovery of pregnancy was met with expulsion from school [10,26]. This review found different policies across countries related to education for adolescent mothers.

Role transition theory explains that the transition process requires supplementation of roles through therapeutic nursing [8]. Three studies explored whether health care providers in clinical setting contributed to transition process of adolescent mothers [17,25,27,30]. All the studies reported on experiences of adolescent mothers about their health care during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum. The adolescent mothers experienced positive as well as negative health care encounters, the negative was reportedly more memorable and hurtful [18,19]. Health workers, and especially nurses, play an important role in each stage of achieving the mother's role. The trend towards shorter hospital stays during the postpartum period limits health care encounters for adolescent mothers. However, there is no standard for health care encounters for adolescent mothers related to maternal and babies' health. Therefore, during their short stay at the hospital, nurses and midwives must help new mothers and their partners to transition and to care for their babies before returning home [33]. It is important to recognize specific adolescent needs [27] offering encouragement and a provide a realistic appraisal of the challenges ahead [19].

This review found factors contributing to the transition to becoming a mother requiring extensive psychological, social, and physical adaptation. However, no studies evaluated cultural and policy related health care contributing to adaptation of adolescent mothers to improve their maternal roles. This is an area that could be explored further.

5. Limitation and implication for future study

This integrative review has some theoretical and methodological limitations. Firstly, most reviewed studies used qualitative methods; hence it is difficult to determine if each factor had significant correlation to effective transition of adolescent mothers. Two studies using quantitative cross-sectional methods and one study using mixed methods showed social support and involvement of the baby's father was associated with maternal identity of adolescent mothers during the transition period. Furthermore, only studies conducted in English language were included so relevant studies published in other languages were not included.

Future studies should aim to build on previous work to clarify relationships between the factors outlined in this review and motherhood transition outcomes. Moreover, further studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of nursing and midwifery interventions in the transition period of young mothers.

6. Conclusion

Our review has presented current knowledge of adolescents' experiences to the motherhood transition and identified influencing factors. Factors found to contribute included physical problems, psychological aspects, caring for the baby, social support, and healthcare provision. Social support was also associated with the development of maternal identity in the transition period of adolescent mothers.

This integrative review contributes to nursing and midwifery science in relation to further understanding the transition of adolescent mothers. Future interventions for adolescent mothers during the transitional period should aim to provide social support and increase the ability of adolescent mothers to deal with the challenges they experience when becoming young mothers.

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thankful to Ministry of Research and Higher Education-Indonesia for support this publication via Enhance International Publication (EIP) on 2018. Thanks to Kusrini Kadar, MN., PhD. for contribution in proofreading the article.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Nursing Association.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.03.013.

Funding

The author received financial support for this research from The Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) of Indonesian government.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.World Health Organization, WHO . WHO; 2004. Adolescent pregnancy: issues in adolescent health and development.http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42903/9241591455_eng.pdf;jsessionid=A892DCC9F0C3841DA9ADC540525DEA30?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Adolescent pregnancy fact sheet. WHO adolesc fact sheet 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112320/WHO_?sequence=1

- 3.Wang C.S., Wang L., Lee C.M. Adolescent mothers and older mothers: who is at higher risk for adverse birth outcomes? Publ Health. 2012;126:1038–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganchimeg T., Ota E., Morisaki N., Laopaiboon M., Lumbiganon P., Zhang J. Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: a World Health Organization multicountry study. Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;121(Suppl):40–48. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Center fo Reproductive Rights . 2013. Accountability for child marriage. New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid V., Meadows-Oliver M. Postpartum depression in adolescent mothers: an integrative review of the literature. J Pediatr Health Care. 2007;21:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mercer R.T. Becoming a mother versus maternal role attainment. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004;36:226–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meleis A.I. Springer Publishing Company; New York, NY: 2010. Experiencing transitions: an emerging middle-range theory. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohammadi N., Montazeri S., Alaghband rad J., Ardabili H.E., Gharacheh M. Iranian pregnant teenage women tell the story of “fast development”: a phenomenological study. Women Birth. 2016;29:303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ngum Chi Watts M.C., Liamputtong P., McMichael C., Chi Watts M.C.N., Liamputtong P., McMichael C. Early motherhood: a qualitative study exploring the experiences of African Australian teenage mothers in greater Melbourne, Australia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:873. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2215-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mercer R.T. Nursing support of the process of becoming a mother. JOGNN - J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:649–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mangeli M., Rayyani M., Cheraghi M.A., Tirgari B. Exploring the challenges of adolescent mothers from their life experiences in the transition to motherhood: a qualitative study. J Fam Reprod Health. 2017;11:165–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheeran N., Jones L., Rowe J. Motherhood as the vehicle for change in Australian adolescent women of preterm and full-term infants. J Adolesc Res. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Zyl L., Van Der Merwe M., Chigeza S. Adolescents' lived experiences of their pregnancy and parenting in a semi-rural community in the Western Cape. Soc Work W. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Copeland R.J. Experiences of adolescent mothers in Costa Rica and the role of parental support. J Fam Soc Work. 2017;20:416–432. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mallette J.K., Futris T.G., Brown G.L., Oshri A. The influence of father involvement and interparental relationship quality on adolescent mothers' maternal identity. Fam Relat. 2015;64:476–489. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheeran N., Jones L., Rowe J. Joys and challenges of motherhood for Australian young women of preterm and full-term infants: an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2015;33:512–527. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrison M.E., Clarkin C., Rohde K., Worth K., Fleming N. Treat me but don't judge me: a qualitative examination of health care experiences of pregnant and parenting youth. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunter L., Magill-Cuerden J., Mccourt C. Disempowered, passive and isolated: how teenage mothers' postnatal inpatient experiences in the UK impact on the initiation and continuation of breastfeeding. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11:47–58. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whittemore R., Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joanna Briggs Institute Critical-appraisal-tools 2017. http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html

- 22.Howard L.C., Stratton A.J. Vol. 53. Ferris State Univ NURS; 2012. Nursing theory of ramona T. Mercer: maternal role attainment - becoming a mother; p. 8. 324. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kagawa R., Daerdorff J., Dominguez Esponda R., Craig D., Fernald L. The experience of adolescent Motherhood : an exploratory mixed methods study. JOGNN - J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2016;38:42–49. doi: 10.1111/jan.13329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gyesaw N.Y.K., Ankomah A. Experiences of pregnancy and motherhood among teenage mothers in a suburb of Accra, Ghana: a qualitative study. Int J Women Health. 2013;5:773–780. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S51528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salusky I. The meaning of motherhood: adolescent childbearing and its significance for poor Dominican females of Haitian descent. J Adolesc Res. 2013;28:591–614. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson-Mitchell K., Bennett J., Stennett R. Psychological health and life experiences of pregnant adolescent mothers in Jamaica. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:4729–4744. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110504729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klingberg-Allvin M., Binh N., Johansson A., Berggren V. One foot wet and one foot dry: transition into motherhood among married adolescent women in rural Vietnam. J Transcult Nurs. 2008;19:338–346. doi: 10.1177/1043659608322419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devito J. How adolescent mothers feel about becoming a parent. J Perinat Educ. 2010;19:25–34. doi: 10.1624/105812410X495523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts S., Graham M., Barter-Godfrey S. Young mothers' lived experiences prior to becoming pregnant in rural Victoria: a phenomenological study. Aust J Rural Health. 2011;19:312–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wahn E., Nissen E., Ahlberg B.M. Becoming and being a teenage mother: how teenage girls in south western Sweden view their situation. Health Care Women Int. 2005;26:591–603. doi: 10.1080/07399330591004917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ngai F.-W., Chan S.W.-C. Psychosocial factors and maternal wellbeing: an exploratory path analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48:725–731. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sartore T.A. Maternal role attainment in adolescent mothers: foundations and implications. Online J Knowl Synth Nurs. 1996;3:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alligood M.R. fifth ed. Mosby/Elsevier; 2014. Nursing theory utilization & application. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nystrom K., Ohrling Kerstin. Parenthood experiences during the child's first year: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;46:319–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.02991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ngai F.W., Chan S.W., Holroyd E. Chinese primiparous women's experiences of early motherhood: factors affecting maternal role competence. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1481–1489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeVito J. Self-perceptions of parenting among adolescent mothers. J Perinat Educ. 2007;16:16–23. doi: 10.1624/105812407X170680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fowles E.R., Horowitz J.A. Clinical assessment of mothering during infancy. JOGNN - J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:662–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hupcey J.E. Clarifying the social support theory-research linkage. J Adv Nurs. 1998;27:1231–1241. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown S.G., Hudson D.B., Campbell-Grossman C., Kupzyk K.A., Yates B.C., Hanna K.M. Social support, parenting competence, and parenting satisfaction among adolescent, African American, mothers. West J Nurs Res. 2018;40:502–519. doi: 10.1177/0193945916682724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.