Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to understand the resilience experiences in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and develop the resilience framework for them.

Methods

Semistructured interviews were conducted with 15 patients with IBD who were purposefully recruited from the gastroenterology department of two hospitals in Jiangsu, China to gain diversity in the demographic and clinical characteristics. The data were analyzed using a directed content analysis approach based on the Kumpfer's resilience framework.

Results

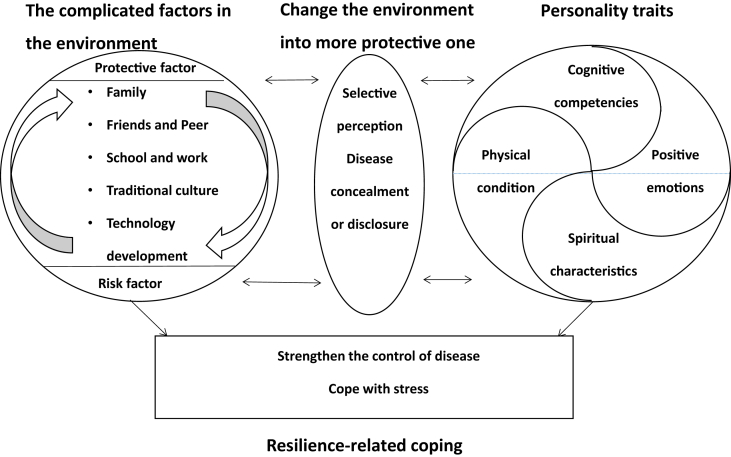

The resilience framework for patients with IBD was formed from the analysis. This framework was composed of four themes, as follows: (1) complicated factors in the environment, (2) change the environment into a protective one, (3) personality traits, and (4) resilience-related coping.

Conclusions

The resilience framework for patients with IBD can effectively characterize the resilience experience of patients during the disease and assist healthcare professionals to understand how patients recover from the disease. More quantitative studies are needed to further explore the influencing factors of resilience and improve resilience in patient with inflammatory Bowel Disease.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Resilience, Psychological, Patients, Qualitative research

1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) includes Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis, which affects approximately 0.5% people in Western countries [1]. With the changes in environment and diet, the incidence of IBD in East Asia has drastically increased. China ranks first in Asia, about 3.44/10 million people in China suffered from IBD [2]. Patients have to suffer from recurrent abdominal pain and diarrhea, as well as expensive treatment costs, which cause life restriction and the occurrence of negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression [3]. Although patients endured both physical and psychological distresses from IBD, some of these patients excel in dealing with distress and enjoy a high quality of life, who are considered to be resilient [4]. Resilience can relieve chronic patients' anxiety and depression [5]. Resilience is also positively correlated with self-efficacy and improved social support and quality of life in other diseases [[6], [7], [8]]. No uniform definition of resilience has been observed since it may not be a single construct but complex processes influenced by both internal and external factors [9].

We speculated that resilience can make a sense in the course of IBD and improve patients’ quality of life. However, empirical literature related to resilience in IBD is scarce. Melinder [10]claimed that adolescents who have low resilience have increased risk to develop IBD in adulthood. Small number of studies have investigated the concepts that belong to positive psychology, such as coping [11], self-efficacy [12], and equilibrium in IBD population [13]. However, these studies have not focused on resilience specifically, and none of these studies have explored the factors that can influence the resilience process.

The aim of our study is to understand why some patients with IBD suffer from both physical and psychological distresses while others still enjoy a high quality of life. Then, we develop a specific resilience framework for patients with IBD in this area of study.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

The descriptive qualitative approach was used to explore the resilience experiences in patients with IBD. Semistructured, face-to-face interviews were performed. Individual interviews can avoid consensus effects and result in considerable data on personal experiences. All interviews were done by the same researcher. All interviews were completed in the conference room of the Department of Gastroenterology, First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University and the Hospital of Nanjing Military Region. Only the researcher and participant were present at the time of the interview.

2.2. Recruitment

The maximum variation sampling approach was used to select participants purposely who are varied in age, gender, course of the disease, marital status, and working condition to gain diverse resilience experiences. Patients with IBD who were hospitalized from October 2016 to February 2017 in the Gastrointestinal Disease Center of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University were considered to be recruited in our study if they met the following criteria: (1) diagnosed with IBD for at least 6 months, (2) conscious and can communicate in Chinese, and (3) provided written informed consent. Patients were excluded if they have other severe diseases, mental disorders, or verbal communication disorders, which may potentially compromise their responses to resilience experience. Potential participants were identified according to the recommendation of healthcare professionals in the gastrointestinal disease center or participants. The details of the study were explained to the targeted patients, and these patients were invited to participate. Recruitment stopped once participants from all a priori identified categories had been interviewed, and data analysis suggested the saturation of themes on the basis of the sample characteristics (i.e., no new code can be recognized in later interviews) [14]. The sample size in our study was 15 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical characters.

| N | Sex | Age (years) | Marital status | Education level | Residence | Occupation | Type | Disease states | IBD Duration (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 73 | Married | C | City | Retire | UC | Active | 30 |

| 2 | Male | 23 | Single | D | Country | Unemployed | CD | Remission | 1 |

| 3 | Female | 29 | Married | D | City | Full time | CD | Remission | 0.5 |

| 4 | Female | 47 | Married | B | Country | Unemployed | CD | Active | 2 |

| 5 | Male | 30 | Married | D | Country | Full time | CD | Remission | 1 |

| 6 | Female | 86 | Widowed | D | City | Retire | UC | Active | 3 |

| 7 | Male | 30 | Married | D | City | Full time | UC | Active | 3 |

| 8 | Female | 54 | Married | A | Country | Unemployed | UC | Active | 4 |

| 9 | Male | 19 | Single | D | City | Attend school | CD | Remission | 0.5 |

| 10 | Female | 30 | Married | D | City | Full time | CD | Remission | 0.6 |

| 11 | Male | 43 | Married | B | Country | Unemployed | UC | Active | 3 |

| 12 | Male | 56 | Married | C | Country | Retire | CD | Active | 8 |

| 13 | Male | 20 | Single | D | City | Attend school | CD | Remission | 5 |

| 14 | Female | 20 | Single | D | Country | Attend school | CD | Remission | 5 |

| 15 | Female | 27 | Single | D | City | Full time | CD | Remission | 8 |

Note: A = Elementary school; B = Middle school; C=High school; D = College or higher; UC = Ulcerative colitis; CD = Crohn disease.

2.3. Data collection

The predesigned interview guide was used to lead the interview. The interview guide was designed based on Kumpfer's resilience framework as well as literature review.

Kumpfer's resilience framework emphasizes that an individual can interact with the environment actively or passively when faced with stressors or challenges and obtain a high quality of life through the dynamic process of resilience [15]. As a major life event, IBD may inevitably bring heavy stress and challenges to patients. Therefore, the experiences of resilience in IBD patients could be probed by Kumpfer's framework of resilience, which consists of six elements: stressor or challenge, the external environment context, person-environment interaction processes, internal resiliency factors, resiliency processes, and the positive outcome. The last part of the framework shows three possible outcomes caused by resiliency process: resilient reintegartion, adaption and maladaptation reintegartion.

This study focused on the intrinsic factors and external environment of resilience, exploring the dynamic process of disease adaptation. Resilience results beyond the scope of our study. On the basis of the framework, we raised questions like“How did you recover from difficulties and challenges which the IBD brought to you?”, “What helped or hindered you from recovering from IBD?”and “What qualities do you have to help you fight the disease?”

Meanwhile, we reviewed literature not limited to resilience, but we also included qualitative studies on IBD as reference. The guide begins with the question “What does IBD mean for you?” and other personal perceptions were solicited afterward, that is, “What are the difficulties and challenges that disease brings to your life?” In accordance to the semi-structured interview techniques, we permitted the order of questions to vary among participant on the basis of variations in individual narratives. When the patient's mood swings during the interview, we will terminate it. The interviews lasted for 30 min to 60 min. All interviews, expressions, tones, and actions of patients during the interview were recorded. The basic questionnaire (which included demographic information) was completed by participant before the interview.

2.4. Data analysis

The primary researcher listened to the recording repeatedly and transcribed it verbatim in Microsoft Word 2010 within 24 h. Transcripts were analyzed by two researchers by using directed content analysis method, which is recommended when existing theories or prior studies on a phenomenon are incomplete or will benefit from further description [16]. Two researchers scanned all transcripts to acquire a global recognition of the data in context. After highlighting the texts involving psychology resilience and giving a predetermined code from the Kumpfer's resilience framework [15], we compared the links among the codes. A new code will be given if the text cannot be categorized with the predetermined coding scheme. The research team met periodically to discuss about the emerged codes and reach a consensus on the concepts and themes.

2.5. Ethical considerations

All participants signed informed consent before the interview. Confidentiality was ensured by the principal researchers. Patients can withdraw from this study any time. The main researchers of this study are nationally certified psychologists that can cope up with the sudden situation during interviews. The study was approved by the First Affiliated Hospital with Nanjing Medical University Ethics Committee on Clinical Investigation.

2.6. Trustworthiness

Multiple methods were used to develop the trustworthiness of the findings guided by Lincoln and Guba [17]. The participants were selected with maximum variation sampling approach to acquire the variety of resilience experiences of patients with IBD, which enhanced the validity. To gain credibility, we used the template, and the first author interviewed all participants and analyzed the data [18]. Data and method triangulation guaranteed the credibility of the codes. We also presented relevant quotations to explain the categories further and strengthen the credibility [19]. To deal with credibility, we provided explanations on how to interpretation was performed for the readers to judge the analysis process [20] (Table 2). The research process was outlined step-by-step (including participant recruitment, data collection, analysis, and study circumstances) enhanced the transfer ability of the finding [21]. The description of the informants were used to portray the participants’ feelings accurately.

Table 2.

Example of the analysis.

| Narrative Text | Concept | Subtheme | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| “When the doctor told me that I got the IBD, anyway, I felt heartbroken and unacceptable, but the family, especially my parents has been enlighten me and gave me a lot of help” [interviewee 5] | Emotional supports from family | Family protective factors | External environmental protective factors |

| “Whenever I feel bad, I will think of those who suffer from cancer or a car accident, compared with them I am very lucky and IBD is not so terrible” [interviewee 10] | Emotional coping | Cope with stress | Resiliency processes |

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Participants were patients with IBD who were hospitalized from October 2016 to February 2017. The average age of participants was 39.07 ± 20.38 years old.

3.2. Findings

Data were collected from people who living with IBD. The majority of the elements in Kumpfer's framework can be explained in this study, while some specific codes emerged from patients with IBD. Four major themes and 13 subthemes emerged from the data, as shown in Table 3. The resilience framework for patients with IBD was formed based on the main findings (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Themes and sub-themes that emerged from the qualitative coding.

| Major Theme | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| The complicated factors in the environment | Family |

| Friends and Peer | |

| School and work | |

| Traditional culture | |

| Technology development | |

| Change the environment into more protective one | Selective perception |

| Disease concealment or disclosure | |

| Personality traits | Cognitive competencies |

| Positive emotions | |

| Physical condition | |

| Spiritual or motivation characteristics | |

| Resilience-related coping | Strengthen the control of disease |

| Cope with stress |

Fig. 1.

Resilience model for patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

3.2.1. Theme 1: complicated factors in the environment

Five main external factors, which played dual roles in patient resilience process, were recognized, as follows: family, friends and peers, school and work, traditional culture, and technology development.

3.2.1.1. Subtheme 1: family

Most of participants emphasized that family is the most important external support for them. Emotional supports, harmonious family atmosphere, understanding, and companionship were frequently mentioned by patients.

3.2.1.2. Subtheme 2: friends and peers

No discrimination and special care for diet from friends encouraged the patients. Some inappropriate ways of concern from friends was also detrimental to the patient's resilience.

A farmer with IBD shared his feeling, “She was too concerned about me and often told me some of the bad consequences of IBD, which makes me very upset.” [Interviewee 11]

As a supplement to the Kumpfer's framework, people who also have IBD were seen as an influencing factor by our participants. The encouragements and disease management experience from peers were necessary strengths for patients. Meanwhile, the deterioration condition of others will make the patients feel sad and damage their self-efficiency.

3.2.1.3. Subtheme 3: school and work

Some patients emphasized the help they received from colleagues, while others expressed psychological distress when they were misunderstood by their teachers or employers. The different intensities of learning and work placed varied pressures and challenges on patients.

“Employers and colleagues are very concerned about me, supports from them gave me the confidence to overcome it (IBD).”[Interviewee 3]

“I am majoring in pharmacy, I worry that frequent leave will affect my studies.” [Interviewee 13]

3.2.1.4. Subtheme 4: traditional culture

China has unique culture, such as share thick and thin and other dialectical thinking of adversity, which may promote patients to find the positive side of IBD and adapt to it well. Meanwhile, other traditional ideology, such as “Ren,” may drive patients to repress their negative emotions.

An undergraduate boy with IBD said: “I seldom talk about my disease to my parents because I do not want them to worry about me.” [Interviewee 13]

3.2.1.5. Subtheme 5: technology development

With the development of technology, patients learn disease knowledge through various ways, which provide promise in learning disease-related knowledge and increases their understanding of IBD. Meanwhile, technology shortens the distance between people and promote communication.

A grandma said, “WeChat helps me connect with my family and friends more frequently.” [Interviewee 6]

3.2.2. Theme 2: change the environment into a protective one

Participants tended to transform the environment around them. Two subthemes were described, as follows: selective perception and disease conceal or disclosure.

3.2.2.1. Subtheme 1: selective perception

Participants tended to take advantages of protective environmental factors and avoid risky ones. For example, participants will selectively browse information online, ignoring negative information that may damage their mental health.

3.2.2.2. Subtheme 2: disease concealment or disclosure

Although some participants said disclosure of disease to others can help them adapt to the disease well, concealing this disease was also a common strategy that participants took to remain normal.

An old man with IBD for many years said, “People around me do not know what is IBD, they may think that the disease is infectious and consequently isolate me.” [Interviewee 1]

3.2.3. Theme 3: personality traits

3.2.3.1. Subtheme 1: cognitive competencies

Studious, industrious, and curiosity were commonly seen in participants who adapted the disease well. When disease relapsed, some participants said that they will reflect and accumulate self-management knowledge from it.

“I am very curious like a child. Curiosity drives me to explore IBD which inspires me to conquer the IBD.” [Interviewee 14]

3.2.3.2. Subtheme 2: positive emotions

Interviews showed that the participants that adapted to IBD well were those who are cheerful and optimistic. Humor was also an important quality that made patients laugh and propel them to find the positive aspects of the disease.

3.2.3.3. Subtheme 3: physical condition

Age appears to be a representative factor of physical condition. In our study, older people were easier to rebound from IBD than younger patients. Basic physical condition also should be taken into consideration.

As a young man said: “I am so young and need to take medicine for a lifetime, which make me feel desperate.” [Interviewee 9]

A girl in our study said: “I was born in poor health, it is more difficult for me to rebound from IBD than the average person.” [Interviewee 14]

3.2.3.4. Subtheme 4: spiritual or motivation characteristics

Spiritual characteristics, such as internal locus of control and self-efficacy, are necessary for resilient patients. Beliefs also play an important part. For Chinese who are edified by Confucian ethics, the impetus to fight IBD was the responsibility for the family.

One woman who was diagnosed with IBD when prepared to marry said, “Disease is under my control, we are a whole, I am good enough to improve the disease.” [Interviewee 3]

3.2.4. Theme 4: resilience-related coping

Resilience-related coping is divided into two categories; one is disease-specific coping style, which is unique for IBD and the other one is common resilience coping style, which everyone would have when faced with life challenges.

3.2.4.1. Subtheme 1: strengthening disease control

Disease-specific coping style was used to strengthen the disease control by our participants, that is, obtaining knowledge on the disease through a variety of approaches and improving self-management ability energetically.

Arrangement and planning ahead were frequently used by some participants to lessen the inconvenience caused by disease.

A participant in college explained how he avoided the effect of the disease on his academics, “Under normal circumstances, I would plan in advance, adjusting the time to go to the hospital according to the schedule.” [Interviewee 13]

3.2.4.2. Subtheme 2: cope with stress

The stress coping strategy used by our participants can be divided into two categories, namely, behavioral and emotional coping methods. The behavioral coping methods, such as distracting attention by listening to music, shopping, sports, going out and travelling, or a resting (e.g., sleeping), were commonly used to relieve negative emotions and enhance strengths.

A soldier with IBD told us, “When I face the pressure, I will cry at will to release my negative emotions.” [Interviewee 7]

Social comparison is one of emotional coping method, which is often taken by participants to gain strength, that is, comparing themselves with those who are more unfortunate than them to gain comfort or learn from patients who have high treatment compliance. Some patients dealt with stress by losing temper or lashing out on others, which may cause damage both to themselves and others.

4. Discussion

Consistent with Kumpfer's resilience framework, environment can buffer or exacerbate the negative effects of stress on patients with IBD. Fergus and Zimmerman [22] suggested that although both protective and risk factors are mentioned in the framework, increased attention should be paid on protective factors. Previous practices in IBD emphasized the improvement of outcomes by recognizing and reducing barriers instead of finding and enhancing protective strength. Our participants emphasize the protective factors.

Similar to the results of Bernhofer [23], our findings showed that the majority of patients recognized family as the most important source of strength. Clinical nurses should evaluate the patient's family environment and encourage them to participate in patient disease management. Although friends were seen as a protective factor, misunderstanding of IBD from friends may harm the patient's resilience. Biased attitudes from others damage the patient's trust and affect their resilience [24]. The related knowledge of IBD in the crowds should be popularize. Peers were chosen as a supplement to Kumpfer's framework in our study. Goffman [25] pointed out that people who have the same “symbol” can form a sincere circle, from which one can obtain spiritual support and be truly accepted as normal people. Similar to the result of Arielle M. Silverman [26], our participants perceived others with IBD as a potential source of emotion or information support. However, negative emotion or disease deterioration from peers may also damage the patient's resilience. Medical workers need to find effective ways to utilize peer resources.

Kumpfer's framework was designed specifically for teenagers; thus, school life is seen as a primary factor [16]. For adults, the influence of work cannot be neglected. The unpredictable, fluctuating nature of IBD makes many patients unemployed despite their desire and ability to work, thereby leading to anxiety and depression [27,28]. Many participants in our study recognized that understanding and support from employers and colleagues gave them strength to rebound from the disease, which was consistent with the results from the study of Teresa Lynch [29]. Meanwhile, another study [30] indicated that resilience and work has no relationship. On one hand, the government needs to consider launching a special employment policy for patients with IBD. On the other hand, as mentioned above, clinical nurses should popularize IBD knowledge not only to patients but also to their family members and friends to improve employers' and colleagues' awareness of the disease.

Regarding culture, China has a distinct culture different from those of Western countries. The religious belief in Kumpfer's framework was rarely mentioned by our participants. Confucianism such as “Ren” and “Li” in Chinese culture make Chinese people tend to repress their inner feelings and have strong endurance to psychology distress. Patients need be encouraged to share their feelings and take the initiative to seek outside help. Researchers paid attention to special traditional culture among different countries.

Technology advance is a new code, which was not included in Kumpfer's framework. The progress of science and technology expand the approaches for patients to obtain the disease information. Meanwhile, information explosion makes choosing the most useful knowledge difficult for patients, which may influence patient resilience. Cooper [4] found that patients with IBD are generally confused with information from different sources and want special IBD doctors or nurses. In addition to the advantages of telemedicine in improving patients' health-related quality of life [31], our participants highlighted the additional functions of technology in communicating with family and friends. Similar to the result of Khan S. [32], the use of telemedicine can promote communication and reduce isolation sense. According to Kumpfer's framework, the individual can adapt well under 1–2 risk factors, but the difficulty increases when more than two risk factors are present. Protective factors can also buffer the role of these risk factors, which suggested that health care providers should be attentive to the protective factors around the living environment of patients with IBD and assist them to eliminate the risk factors and improve their resilience.

Similar to Kumpfer's resilience framework, people with IBD were apt to transform the surrounding environment. Disease concealment or disclosure were frequently used. Some people concealed their disease due to the perceived taboo surrounding the symptoms of the disease [33], which was also reflected by our participants. Concealment may help patients create a false appearance of normal and avoid prejudice from others. However, it inevitably aggravates psychological burden and leads to the emergence of stigma [34]. Taking medication in certain occasions is difficult for patients because of disease concealment, thereby decreasing medication compliance. IBD disclosure is conducive to accept the disease, gain understanding, and receive support from other people [35]. Similar to the findings of Micallef [36], to study whether disclosure disease is context-dependent, our study emphasized on the importance of normalizing IBD and creating supportive environments for people with IBD.

Kumpfer proposed the opinion on the basis of literature review, showing that resilience is the dynamic process that people can rebound from challenges. Resilient patients used a variety of methods to rebound from IBD. Our participants actively sought disease information [37]. The more knowledge the patients learned is, the easier it is to accept and manage IBD [38]. The Internet and health care workers are the main sources for this information. This result suggested that health care workers should pay attention to the patient's information needs and provide targeted information.

Some papers [[39], [40], [41]] showed that quality of life can be improved by a positive coping style. Behavior-focused strategies, such as distraction, were frequently taken by our participants to cope with stress [11]. Strategies such as social comparison and positive attitudes that is also called emotion-focused strategies are useful for patients to rebound from IBD, which was inconsistent with the conclusion from a meta-analysis [42], wherein emotion-focused strategies are negatively associated with health outcome. This disagreement may be due to the different strategies used. Distance and avoidance, which were mentioned by Penley JA [42], may harm the patients, while some emotion-focused strategies, such as social comparison, which have been used by our participants, may help patients with IBD to maintain normal life [43].

5. Limitations

Kumpfer's resilience framework has more elements than the one we used in this study. However, we also found some new elements, which were specifically present for patients with IBD. Some participants who have been diagnosed with IBD for a long time often provided their resilience experience through recalling. Reframing their memory to experiences may have influenced the credibility of this study. The participants in this study were only recruited from two hospital. Although both hospital are national first-class hospitals (third-grade class A) and patients in the gastrointestinal disease center all came from different parts of the country, the transferability of the results will be affected. Other multicenter studies that use longitudinal design are needed to explore the process of resilience and verify the accuracy of the resilience framework for patients with IBD.

6. Conclusion

The resilience framework for patients with IBD can effectively characterize the resilience experience of patients during the course of the disease and assist healthcare professionals to understand how patients recover from disease. However, differences in resilience factors and process are significant among individuals, and other multicenter longitudinal studies are needed to verify the accuracy of this framework.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no financial support or conflicts of interest to report.

Funding

This work was supported by the Special Project of Philosophy and Social Science Development of Nanjing Medical University (grant no. 2017ZSZ007).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all patients who participated in this study. This work was supported by the Jiangsu Innovation Medical Team and the Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Nursing Association.

References

- 1.Kaplan G.G. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(12):720–727. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng S.C. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: focus on Asia. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28(3):363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrell D., Savage E. Symptom burden: a forgotten area of measurement in inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Nurs Pract. 2012;18(5):497–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2012.02063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper J.M., Collier J., James V., Hawkey C.J. Beliefs about personal control and self-management in 30-40 year olds living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(12):1500–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gloria C.T., Steinhardt M.A. Relationships among positive emotions, coping, resilience and mental health. Stress Health. 2016;32(2):145–156. doi: 10.1002/smi.2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan-Kristanto S., Kiropoulos L.A. Resilience, self-efficacy, coping styles and depressive and anxiety symptoms in those newly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20(6):635–645. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.999810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore R.C., Eyler L.T., Mausbach B.T., Zlatar Z.Z., Thompson W.K., Peavy G. Complex interplay between health and successful aging: role of perceived stress, resilience, and social support. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23:622–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman A.M., Molton I.R., Alschuler K.N., Ehde D.M., Jensen M.P. Resilience predicts functional outcomes in people aging with disability: a longitudinal investigation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:1262–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richardson G. The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58(3):307–321. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melinder C., Hiyoshi A., Fall K., Halfvarson J., Montgomery S. Stress resilience and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study of men living in Sweden. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsson K., Loof L., Nordin K. Stress, coping and support needs of patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease: a qualitative descriptive study. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(5–6):648–657. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zijlstra M., De Bie C., Breij L., van Pieterson M., van Staa A., de Ridder L. Self-efficacy in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a pilot study of the “IBD-yourself”, a disease-specific questionnaire. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7(9):e375–e385. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sykes D.N., Fletcher P.C., Schneider M.A. Balancing my disease: women's perspectives of living with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(15–16):2133–2142. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guest G., Arwen B., Johnson How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumpfer K.L. Sage Publications, Springer; 2002. Factors and processes contributing to resilience--the resilience framework; pp. 179–224. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh H.F., Shannon S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lincoln Y.S., Guba E.G. Sage Publications; Newbury Park Ca: 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fereday J., Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patton M.Q. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, US: 2002. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morse J.M., Barrett M., Mayan M., Olson K., Spiers J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2002;1:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fergus S., Zimmerman M.A. Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernhofer E.I., Masina V.M., Sorrell J., Modic M.B. The pain experience of patients hospitalized with inflammatory bowel disease: a phenomenological study. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2015;40(3):200–207. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishio I., Chujo M. Qualitative analysis of the resilience of adult Japanese patients with type 1 diabetes. Yonago Acta Med. 2016;59(3):196–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goffman E. Prentice Hall Publications; Englewood Cliffs, US: 1963. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverman A.M., Verrall A.M., Alschuler K.N., Smith A.E., Ehde D.M. Bouncing back again, and again: a qualitative study of resilience in people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(1):14–22. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2016.1138556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramos A., Calvet X., Sicilia B., Vergara M., Figuerola A., Motos J. IBD-related work disability in the community: prevalence, severity and predictive factors. A cross-sectional study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3(4):335–342. doi: 10.1177/2050640615577532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Restall G.J., Simms A.M., Walker J.R., Graff L.A., Sexton K.A., Rogala L. Understanding work experiences of people with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(7):1688–1697. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynch T., Spence D. A qualitative study of youth living with Crohn disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2008;1(3):224–230. doi: 10.1097/01.SGA.0000324114.01651.65. quiz 231-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Black J.K., Balanos G.M., Whittaker P.P.A. Resilience, work engagement and stress reactivity in a middle-aged manual worker population. Int J Psychophysiol. 2017;116:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tu W., Xu G., Du S. Structure and content components of self-management interventions that improve health-related quality of life in people with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(19–20):2695–2709. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan S., Dasrath F., Farghaly S., Otobo E., Riaz M.S., Rogers J. Unmet communication and information needs for patients with IBD: implications for mobile health technology. Br J Med Res. 2016;12(3) doi: 10.9734/BJMMR/2016/21884. pii: 12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daniel J. Young adults' perceptions of living with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2001;25(3):83–94. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saunders B. Stigma, deviance and morality in young adults' accounts of inflammatory bowel disease. Sociol Health Illness. 2014;36(7):1020–1036. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barned C., Stinzi A., Mack D., O'Doherty K.C. To tell or not to tell: a qualitative interview study on disclosure decisions among children with inflammatory bowel disease. Soc Sci Med. 2016;16:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Micallef-Konewko E. Professional doctorate thesis. University of East London; 2013. Talking about an invisible illness: the experience of young people suffering from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lovén Wickman U., Yngman-Uhlin P., Hjortswang H., Riegel B., Stjernman H., Hollman Frisman G. Self-care among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: an interview study. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2016;39(2):121–128. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lesnovska K.P., Börjeson S., Hjortswang H., Frisman G.H. What do patients need to know? Living with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(11–12):1718–1725. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mussell M., Böcker U., Nagel N., Singer M.V. Predictors of disease-related concerns and other aspects of healthrelated quality of life in outpatients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;12:1273–1280. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200412000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nicholas D.B., Otley A., Smith C., Avolio J., Munk M., Griffiths A.M. Challenges and strategies of children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a qualitative examination. Health Qual Life Outcome. 2007;25:28. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larsson K., Lööf L., Rönnblom A., Nordin K. Quality of life for patients with exacerbation in inflammatory bowel disease and how they cope with disease activity. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(2):139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Penley J.A., Tomaka J., Wiebe J.S. The association of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes: a meta-analytic review. J Behav Med. 2002;25:551–603. doi: 10.1023/a:1020641400589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall N.J., Rubin G.P., Dougall A., Hungin A.P., Neely J. The fight for 'health-related normality': a qualitative study of the experiences of individuals living with established inflammatory bowel disease (ibd) J Health Psychol. 2015;10(3):443–455. doi: 10.1177/1359105305051433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]