Abstract

Objective:

While a number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or cognitive impairment have been identified, independent replications remain the only way to validate proposed signals. We investigated SNPs in candidate genes associated with either cognitive impairment or AD pathogenesis and their relationships with probable dementia (PD) in the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS).

Methods:

We analyzed 96 SNPs across five genes (APOE/TOMM40, BDNF, COMT, SORL1, and KIBRA) in 2857 women (ages ≥ 65) from the WHIMS randomized trials of hormone therapy using a custom Illumina GoldenGate assay; 19% of the sample were MCI (N=165) or PD (N=387), and the remaining 81% were free of cognitive impairment. SNP associations were evaluated for PD in non-Hispanic whites adjusting for age and HT using logistic regression under an additive genetic model.

Results:

One SNP (rs157582), located in the TOMM40 gene nearby APOE, was associated with the PD phenotype based on a p-value accounting for multiple comparisons. An additional 12 SNPs were associated with the PD phenotype at p≤0.05 (APOE: rs405509, rs439401; TOMM40: rs8106922, and KIBRA: rs4320284, rs11740112, rs10040267, rs13171394, rs6555802, rs2241368, rs244904, rs6555805 and rs10475878). Results of the sensitivity analyes excluding MCI were similar, with addition of COMT rs737865 and BDNF rs1491850 (p≤0.05).

Conclusions:

Our results in older women provide supporting evidence that the APOE/TOMM40 genes confer dementia risk and extend these findings to COMT, BDNF and KIBRA. Our findings may lead to a better understanding of the role these genes play in cognition and cognitive impairment.

Keywords: MCI, aging, hormone therapy, Alzheimer’s disease, AD

INTRODUCTION

As our knowledge of the genetic and molecular basis of aging grows, the hope is that both common and divergent pathways for normal brain aging and neurodegeneration may be uncovered. Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a progressive, age-related neurodegenerative disorder and the most common cause of dementia, remains one of the leading causes of death in the developed world (Alzheimer’s Association 2017). As predictions indicate that 5 million Americans are living with AD and this number is expected to quadruple by 2050 (Heron 2016; Alzheimer’s Association 2017), it is increasingly important to find effective preventative and therapeutic interventions. Progress is hindered, at least in part, by the similarities between normal age-associated and disease-related, pathological changes in cognition, especially in the early stages of disease.

Genes are considered good contenders as contributors to variation in a particular phenotype if they are functionally polymorphic and have some relevance to the trait under consideration (Glatt and Freimer 2002). These criteria guide our focus on five genes implicated in memory and other cognition functions, and possibly the neuropathology of AD, at the time of the study inception: (1) apolipoprotein E (APOE)/TOMM40, (2) sortilin-related receptor (SORL1 or SORLA), (3) catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), (4) brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and (5) KIBRA (KIAA0869 or WWC1) genes. Since, a number of large-scale GWAS have implicated novel AD genes and their variants, currently beyond our scope.

APOE presents a genetic polymorphism with three common alleles: ε2, ε3, and ε4. The ε4 allele, located on chromosome 19q13.2, is the most consistent genetic risk for late onset AD (Corder etal., 1993; Kehoe et al. 1999) and has been implicated in many biochemical AD disturbances, such as neuronal cell death, oxidative stress, synaptic plasticity and cholinergic signaling dysfunction (Cedazo-Minguez and Cowburn, 2001). At least some APOE-ε4 cognitive deficits are related to early AD pathology, with subtle differences between APOE genotypes in mid-adulthood, prior to the onset of the prodromal period (O’Donoghue et al. 2018). More recently, deep sequencing of the APOE region revealed a polymorphic poly-T repeat located in the intron of TOMM40, the longer lengths of which have been associated with a higher risk and earlier onset of AD in two independent clinical cohorts (Roses et al. 2010). A meta-analysis of GWASs of 31 cohorts suggests significant associations between general cognitive function and both TOMM40 and APOE (Davies et al 2015).

The neuronal sortilin-related receptor (SORL1, also SORLA or LR11) is located on chromosome 11q23.2-q24.2 and encodes a 250-kD membrane protein expressed in neurons of the central and peripheral nervous system (Andersen et al. 2005) with known involvement in intracellular trafficking between the membrane and intracellular organelles (Annaert and De Strooper, 2002). Under-expression of SORL1 leads to over-expression of amyloid-β (Aβ), which in turn is associated with an increased risk of AD (Reitz and Mayeux, 2009). Polymorphisms across SORL1 have been associated with AD in several cohorts (Rogaeva et al. 2007; Webster et al. 2007)

Catechol-O-methyl Transferase (COMT) plays a pivotal role in the modulation of fronto-striatal network activity. A functional single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of COMT (val158met) located on chromosome 22q11 results in the substitution of valine (val) with methionine (met) at codon 158 of the protein sequence. The met allele produces an enzyme that is unstable and has only half the activity of the val-containing polypeptide Egan et al. 2001). Biologic and genetic findings suggests potential mechanisms for the role of COMT in the pathophysiology of dementia (Serretti and Olgiati, 2012); for example, COMT inhibitors improve executive memory in normal subjects and block beta-amyloid fibrils in vitro. Prior association studies of COMT and AD risk, however, have yielded inconsistent findings (Flirski et al., 2011; Perkovic et al 2018).

Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) is a neurotrophin expressed throughout the brain, particularly in the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus (Pezawas et al., 2004). The BDNF gene, composed of five or more exons, is located on chromosome 11p13. A frequent non-conservative SNP in the gene producing a val to met substitution at codon 66 (val66met) affects the activity dependent secretion of BDNF (Egan et al., 2003). While BDNF is involved in biologic mechanisms thought to underlie learning and memory (Figurov et al., 1996; Lee et al., 2004; Baquet et al., 2004; Gorski et al., 2003), the met allele is associated with worse memory and executive function (Savitz et al., 2006). Literature on whether BDNF genetic variations confer AD risk remains conflicting, although a meta-analysis reports a significant association between Val66Met and AD in women, but not in men (Fukumoto et al., 2010).

The first hypothesis free GWAS study in cognition revealed a previously unknown association of the KIBRA gene with episodic memory in 351, confirmed in a separate sample of 256, cognitively intact adults (ages 20–81; Papassotiropoulos et al., 2006). Rs17070145, a common T to C substitution within the ninth intron of KIBRA located on chromosome 5q34 encoding a neuronal protein was associated with memory (Papassotiropoulos et al., 2006; Schaper et al., 2007). While KIBRA seems to influence episodic memory in later life, it does not seem to increase the MCI risk (Almeida et al., 2008) and the literature suggests a modest role in AD risk (Burgess et al., 2011).

Here we investigate the relationships of variations in the APOE/TOMM40, BDNF, COMT, SORL1 and KIBRA genes with probabledementia within the randomized clinical trials of hormone therapy (HT) of the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS; Shumaker et al. 1998).

METHODS

Participants.

The current study is based on secondary analysis of existing data collected through the WHIMS (Shumaker et al. 1998) nested within the randomized HT clinical trials of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), initiated in 1992. Blood specimens for DNA were collected in the WHI. Specimens selected for genotyping in the present study included all of the mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and probable dementia (PD) cases and a sample of unimpaired controls that were similar with respect to age from WHIMS. The phenotype and age were defined based on the last observation on or before a January 2014 data cutoff.

The primary aim of the WHI HT trials was to assess whether conjugated equine estrogen (CEE; 0.625 mg/day) alone or in combination with medroxyprogesterone acetate (CEE+MPA; 2.5mg/day) would reduce the risk of coronary heart disease; other cardiovascular diseases, cancers and hip and other fractures were secondary outcomes. Participants were randomly assigned with equal probability to therapy (CEE if prior hysterectomy; CEE+MPA if no prior hysterectomy) or matching placebos. The WHIMS added the additional outcomes of global cognitive function and cognitive impairment (WHIMS; 1998). The WHIMS clinical trial design, eligibility criteria, and recruitment procedures have been published (Shumaker et al. 1998). Race-ethnicity was collected by self-administered questionnaire at WHI baseline.

Ascertainment of Probable Dementia (PD) and MCI.

A detailed description of the WHIMS four-phase protocol for detecting PD and MCI has been published (Shumaker et al. 1998; Coker et al., 2010). Briefly, participants were screened annually with the Modified Mini Mental State exam (Teng, 1987) during in-clinic visits at 39 participating WHI sites in the U.S. For participants who scored below a pre-set score, the CERAD neurocognitive test battery was administered and a complete neuropsychiatric evaluation was conducted that optionally included a brain CT scan (without contrast) and standard blood assay panel. In addition, a friend or family member familiar with the participant’s functional status was interviewed. All assessments were submitted to a central adjudication panel at the WHIMS Coordinating Center at Wake Forest University School of Medicine for classification as having MCI, PD, or no cognitive impairment based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) (APA 1994). Clinic visits were terminated when WHI entered an extension study in 2008. WHIMS transitioned to a telephone-administered cognitive assessment and proxy interview with the Dementia Questionnaire (Kawas et al). The neurocognitive battery was independently validated (Rapp et al., 2012) and centralized adjudication remained the same.

Gene and SNP Selection.

We analyzed SNPs in five genes chosen based on previously shown associations with either different aspects of cognition or AD pathogenesis. Haplotype tagging SNPs (tSNPs) were selected from the International Haplotype Map project (www.hapmap.org) using a bulk download of tag SNP data. To ensure robust haplotype tagging within the cohort, we selected SNPs based upon a pairwise r2 of greater than 0.8 and a minor allele frequency of greater than 0.2, all based on CEPH Caucasian data typed as a part of the HapMap project. Five regions were studied; all exons of BDNF, KIBRA, APOE and COMT plus at least 20kb of 5’ and 3’ flanking sequence were selected for tSNP analysis producing a list of 75 SNPs required to tag the genes. The region on chromosome 19 was defined based on the APOE gene at the time of study design, however, TOMM40, located next to the APOE gene in a region of strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) has been identified since by deep sequencing (Roses et al., 2009). The SNPs that currently are considered to fall under TOMM40 include: rs157580, rs157582, rs405697, and rs8106922. Although a majority of the SNPs were selected from the International Haplotype Map project (www.hapmap.org) to tag the genes; a few were missense SNPs with previously reported associations with related phenotypes (Supplementary Materials – Table 1). These include the SNPs that make up the common ε2, ε3 and ε4 APOE haplotypes (rs7412 and rs429358) and other well-established non-synonymous alterations in the five gene regions to produce a total of 96 SNPs to be assayed. The two variants that make up the APOE ε2, ε3 and ε4 haplotypes were included regardless of predicted quality control issues on Illumina custom chip and failed QC as expected.

Since, WHI GWAS was performed and genotype results from two SNPs, rs429358 and rs7412, based on imputation and harmonization of genetic data across WHI, were used to define APOE epsilon 2/¾ genotypes for description in our study population and adjustment in regression models. The quality of this imputation was very high with R2 = 0.98 for each SNP.

DNA and Genotyping.

DNA was extracted by the Specimen Processing Laboratory at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center using specimens collected at the time of WHI enrollment. All assays were performed in the Laboratory of Neurogenetics at the National Institute on Aging, using a custom Illumina GoldenGate assay. Custom assay design was initiated with Illumina; this process usually requires 2 iterations based on SNP genotyping likelihood scores generated for each chosen SNP. In our experience 80% of the initially selected SNPs are approved; the remaining 20% of SNPs are each replaced by one or more tagging SNPs that capture the necessary haplotype information and submitted for approval. This process occurs twice. The final genotyping panel r included 96 SNPs. We used between 10–25 ng of DNA for each reaction.

Each GoldenGate assay required 250ng of genomic DNA and each assay was run in a 96-well plate format with each plate consisting of 92 study samples and 4 replicate samples from CEPH families 1347 and 1331 to provide quality assurance of plate orientation and genotype reproducibility. Genotype calling was performed using the algorithms within BeadStudio (Illumina Inc, San Diego CA), and genotype cluster files were generated using a minimum of 1,000 individuals.

Genotyping Quality Control.

Genotyping was done on 96 SNPs and 3,005 samples. 2.3% (69) additional samples were genotyped as blind duplicates. 13 SNPs were flagged as having a call rate <0.90: 5 SNPs had no calls (rs1862355, rs7412, rs4633, rs6267, rs165774), 5 additional SNPs had a call rate <0.85 (rs10074534, rs6887919, rs6555812, rs12285364, rs429358), and 3 SNPs had a call rate of 0.89 (rs2287703, rs11738934, rs668387). Heterozygote rates were flagged when >0.90 or <0.10; 144 individuals were flagged as having a call rate <0.80: 17 had no calls, an additional 21 had call rate <0.70, and 106 had a call rate from 0.70 to 0.80. Analysis of blind duplicates yielded 16 blind duplicate pairs with a concordance rate <0.95, of which 13 were <0.82. The overall concordance rate among blind duplicate samples was 91.7% (range 67.3–100%) among the 91 SNPs with calls. For each SNP association with p≤0.05, the control group’s genotyping data was examined for a strong deviation (p<0.0001) from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Statistical Analyses.

Two phenotypes were defined for analyses: 1) probable dementia (PD) versus all others; and 2) the sensitivity analyses excluding MCI. Initial analyses were performed in non-Hispanic whites only. This was followed up by sensitivity analyses excluding MCI, and inclusion of APOE or APOE+COMT as covariates. HT assignment was defined as CEE-alone, CEE-alone placebo, CEE+MPA, or CEE+MPA placebo. To evaluate the associations between phenotypes and single-SNP genotypes, multiple logistic regression analysis was performed, controlling for age and clinical trial arm (reference: CEE+MPA placebo). Associations were tested using a chi-squared statistic under an additive genetic model and expressed as adjusted odds ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. For each regression model, all participants with complete data on phenotype and covariates, and with genotype data meeting quality control, were included. No covariate interaction terms were added. Uncorrected p values were reported together with a Bonferroni-corrected threshold to account for number of SNPs; no correction was calculated for the two related phenotypes. All analyses were conducted using S+ statistical software (TIBCO Spotfire S+ Version 8.2, TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA).

RESULTS

Genotyping was done on 3005 individuals, including 69 blind duplicate samples. Genotyping quality control criteria were met on a total of 2857 individuals. This final sample was enriched, by design, for cases of cognitive impairment, with 19% (N=552) MCI (N=165) or PD (N=387); the remaining 81% (N=2305) had neither MCI nor dementia. Demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women by cognitive status [mean ± SD or count (column percent)]

| Characteristic | Control Group (N = 2305) | MCI Cases (N = 165) | PD Cases (N = 387) | Overall P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) at last cognitive assessment, mean ± SD | 81.4 ± 5.1 | 81.7 ± 5.7 | 81.7 ± 4.9 | 0.45 |

| Education, n (%) | 0.15 | |||

| High school or less | 660 (28.7) | 57 (34.6) | 128 (33.2) | |

| Some college | 943 (41.0) | 66 (40.0) | 140 (36.3) | |

| College graduate | 700 (30.4) | 42 (25.5) | 118 (30.6) | |

| Race-ethnicity n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| African American | 164 (7.1) | 25 (15.2) | 42 (10.9) | |

| Hispanic | 41 (1.8) | 8 (4.9) | 11 (2.8) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 2033 (88.2) | 128 (77.6) | 323 (83.5) | |

| Other/unknown | 67 (2.9) | 4 (2.4) | 11 (2.8) | |

| WHI HT assignment, n (%) | 0.054 | |||

| Hormone therapy | 1134 (49.2) | 75 (45.5) | 213 (55.0) | |

| Placebo | 1171 (50.8) | 90 (54.6) | 174 (45.0) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 28.7 ± 5.8 | 28.4 ± 5.8 | 27.8 ± 5.5 | 0.023 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 179 (7.8) | 16 (9.8) | 43 (11.1) | 0.068 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1113 (48.3) | 96 (58.2) | 220 (56.9) | <0.001 |

| Stroke n (%) | 29 (1.3) | 8 (4.9) | 10 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| MI, n (%) | 72 (3.1) | 7 (4.2) | 20 (5.2) | 0.11 |

| Coronary revascularization, n (%) | 60 (2.6) | 3 (1.9) | 18 (4.8) | 0.055 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 0.74 | |||

| Current | 130 (5.7) | 11 (6.8) | 21 (5.6) | |

| Former | 892 (39.1) | 61 (37.4) | 135 (35.8) | |

| Never | 1258 (55.2) | 91 (55.8) | 221 (58.6) | |

| Alcohol intake, n (%) | 0.0036 | |||

| Never | 286 (12.5) | 24 (14.6) | 59 (15.5) | |

| Past | 438 (19.1) | 32 (19.4) | 92 (24.2) | |

| < 1 drink/week | 745 (32.5) | 71 (43.0) | 112 (29.4) | |

| 1 to <7 drinks/week | 550 (24.0) | 23 (13.9) | 79 (20.7) | |

| ≥ 7 drinks/week | 272 (11.9) | 15 (9.1) | 39 (10.2) | |

| APOE genotype (imputed), n (%)† | <0.001‡ | |||

| ɛ2/ɛ2 | 11 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | |

| ɛ2/ɛ3 | 244 (12.9) | 14 (12.4) | 26 (8.7) | |

| ɛ2/ɛ4 | 50 (2.7) | 2 (1.8) | 7 (2.4) | |

| ɛ3/ɛ3 | 1201 (63.5) | 61 (54.0) | 132 (44.3) | |

| ɛ3/ɛ4 | 354 (18.7) | 32 (28.3) | 114 (38.3) | |

| ɛ4/ɛ4 | 30 (1.6) | 4 (3.5) | 18 (6.0) |

MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment; PD = probable dementia; SD = standard deviation; HT = hormone therapy; BMI = body mass index; MI = myocardial infarction; APOE = Apolipoprotein E

P values were calculated for comparison of characteristics across the three cognitive impairment groups based on 1) means and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), or 2) distribution of counts and chi-square for data cross-classified by nominal variables into contingency tables (r rows x c columns)

Non-Hispanic whites only

P value for comparison between high risk as defined by (ɛ3/ɛ4 or ɛ4/ɛ4) and low risk (ɛ2/ɛ2, ɛ2/ɛ3, or ɛ3/ɛ3)

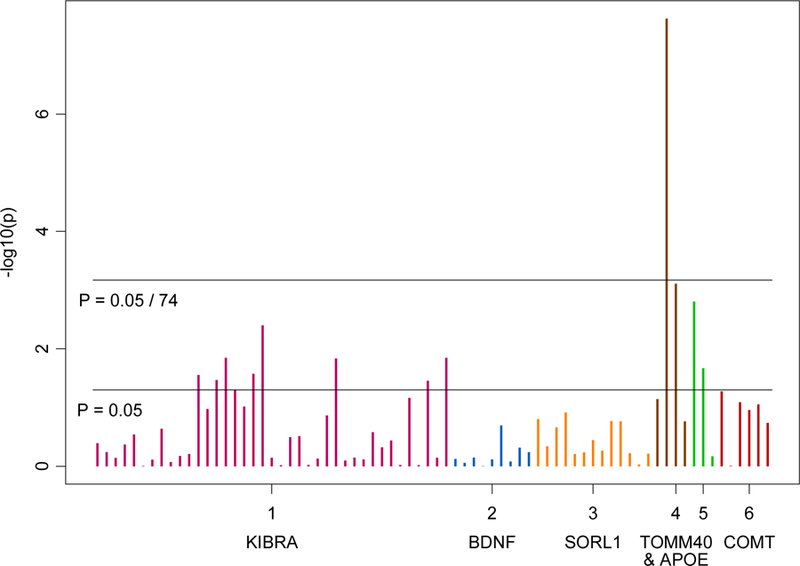

A summary of associations between SNPs that passed quality control in APOE/TOMM40, SORL1, COMT, BDNF, and KIBRA and PD (including and excluding MCI cases) is presented in Table 2. One SNP in the APOE/TOMM40 (rs157582) gene was significantly associated with the PD phenotype, after correcting for multiple comparisons (p≤0.0007). An additional 12 SNPs (Figure 1) were associated with the PD phenotype at p≤ 0.05(APOE: rs405509, rs439401; TOMM40: rs8106922; and KIBRA: rs4320284, rs11740112, rs10040267, rs13171394, rs6555802, rs2241368, rs244904, rs6555805 and rs10475878).

Table 2.

Adjusted SNP associations with the PD phenotype in non-Hispanic whites (with and without MCI); p≤0.05 only.

| Gene Region | SNP | Alleles* | Allele Frequency† | Odds Ratio‡ | 95% CI‡ | P Value‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | KIBRA | rs6555802 | A/C | 0.35 | 1.19 | (1.02, 1.39) | 2.8 × 10−2 |

| rs11740112 | A/G | 0.57 | 0.850 | (0.731, 0.988) | 3.4 × 10−2 | ||

| rs10475878 | A/G | 0.29 | 1.22 | (1.04, 1.43) | 1.4 × 10−2 | ||

| rs6555805 | C/T | 0.75 | 1.19 | (1.00, 1.41) | 5.0 × 10−2 | ||

| rs13171394 | A/G | 0.57 | 1.19 | (1.02, 1.38) | 2.7 × 10−2 | ||

| rs4320284 | G/T | 0.42 | 1.25 | (1.07, 1.45) | 4.0 × 10−3 | ||

| rs2241368 | C/T | 0.24 | 1.23 | (1.04, 1.46) | 1.5 × 10−2 | ||

| rs10040267 | A/G | 0.41 | 0.843 | (0.720, 0.988) | 3.5 × 10−2 | ||

| rs244904 | A/G | 0.48 | 0.827 | (0.710, 0.962) | 1.4 × 10−2 | ||

| TOMM40 | rs157582 | A/G | 0.20 | 1.64 | (1.38, 1.94) | 2.4 × 10−8 | |

| rs8106922 | A/G | 0.59 | 1.31 | (1.12, 1.52) | 7.8 × 10−4 | ||

| APOE | rs405509 | A/C | 0.48 | 1.28 | (1.10, 1.49) | 1.6 × 10−3 | |

| rs439401 | C/T | 0.63 | 1.21 | (1.03, 1.42) | 2.1 × 10−2 | ||

| MCI excluded | KIBRA | rs4320284 | G/T | 0.42 | 1.21 | (1.02, 1.44) | 2.8 × 10−2 |

| rs2241368 | C/T | 0.24 | 1.35 | (1.12, 1.64) | 1.9 × 10−3 | ||

| rs244904 | A/G | 0.48 | 0.809 | (0.679, 0.963) | 1.7 × 10−2 | ||

| BDNF | rs1491850 | C/T | 0.44 | 0.810 | (0.681, 0.962) | 1.6 × 10−2 | |

| TOMM40 | rs157582 | A/G | 0.20 | 1.80 | (1.48, 2.18) | 2.1 × 10−9 | |

| rs8106922 | A/G | 0.59 | 1.43 | (1.20, 1.72) | 9.0 × 10−5 | ||

| APOE | rs405509 | A/C | 0.48 | 1.41 | (1.19, 1.68) | 1.1 × 10−4 | |

| COMT | rs737865 | C/T | 0.27 | 0.762 | (0.622, 0.933) | 8.7 × 10−3 |

CI = confidence interval; HT = hormone therapy; MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment; PD = probable dementia

Alleles are ordered as effect allele/ other allele. The effect allele is the first of the two alleles after alphabetizing. The direction of odds ratio reflects the “effect” of this allele.

Overall observed frequency for the effect allele

Odds ratio measures of SNP association, 95% CI, and p value results are based on multiple logistic regression models with covariates age at last observation, WHI HT assignment status (CEE-alone, CEE-alone placebo, CEE+MPA, and CEE+MPA placebo), and one SNP in each model; the Bonferroni-corrected threshold for SNP association p values is 7 × 10−4.

The results with inclusion of all race-ethnic groups were similar (results not shown).

Figure 1.

Associations between SNPs in APOE/TOMM40, BDNF, COMT, SORL1, and KIBRA and PD phenotype.

The results were similar when sensitivity analysis was performed excluding MCI; the APOE/TOMM40 (rs157582) remained significant after correcting for multiple comparisons. An additional 7 SNPs were found to be associated with the PD phenotype at p≤ 0.05 (APOE/TOMM40: rs8106922; COMT: rs737865; BDNF: rs1491850; and KIBRA: rs4320284, rs2241368, and rs244904).

The results for the entire sample compared to non-Hispanic whites only were similar (data not shown). When we repeated the analysis adding APOE as a covariate, as there is a chance that signal in APOE/TOMM40 may be in linkage disequilibrium with the two APOE ε–4 allele variants defining epsilon 2/¾ genotypes (and alternately adding both APOE and COMT rs4680 to test for synergistic effects reported in the literature), the results were unchanged and no new SNPs were significant. Inferences were nearly identical for the sensitivity analysis (excluding MCI).

DISCUSSION

Our results in older women provide additional support for a role of APOE/TOMM40 in dementia risk (Kehoe et al. 1999) and provide a validation for our general approach to investigation of GWAS signals related to cognitive impairment. The APOE-ε4 allele Is already known to be associated with cognition-related phenotypes in WHIMS (Cacciattolo et al. 2017; Goveas et al. 2016; Mozhui et al. 2017). Our results in older women are in line with and provide additional support for a role of APOE/TOMM40 in dementia risk (Kehoe et al. 1999). A comprehensive search for AD susceptibility loci in the APOE region suggests that APOE alleles could essentially account for all the inherited AD risk and that other variants, including poly-T-track in TOMM40, do not seem to pose independent risks (Jun et al., 2012). In our sample, the results remained largely unchanged when APOE SNPs that define epsilon 2/¾ genotypes were added to the analyses as covariates.

Although several studies have confirmed SORL1 as a non-APOE genetic risk locus (Beecham et al., 2014; Chouraki & Seshadri, 2014; Jin et al., 2013; Karch and Goate, 2015), we did not observe significant associations of SORL1 with cognitive impairment in our female sample. Our results suggest associations of COMT with PD. We did find associations for the loci in both COMT and KIBRA genes, although they did not survive the stringent Bonferroni correction. Our findings remain similar when sensitivity analyses were performed excluding MCI cases, with an additional significant signal in one of the BDNF SNPs (rs1491850), which also did not survive Bonferroni adjustment.

There is a general lack of understanding of the relationship between COMT and AD (but see Lin et al., 2012; Pereira et al., 2012), although there is a suggestion of a synergistic effect between COMT’s GG (Val/Val) and APOE ε–4 allele in increasing risk for MCI and AD that may be more pronounced in males (Lanni et al., 2012). Some have suggested that a combination of genetic polymorphisms involved in normal cognitive aging (such as COMT) and AD (such as APOE) may contribute to genetic heterogeneity in cognitive impairment (Dixon et al., 2014). In our sample, the results remained unchanged when both APOE and COMT rs4680 were added to the analyses as covariates. Overall, we report an association for loci in the KIBRA gene with cognitive impairment, in agreement with the the literature suggesting that KIBRA is modestly associated with predisposition for late-onset AD (Corneveaux et al., 2010; Burgess et al., 2011). Current literature also highlights the multifactorial complexity of KIBRA, given the evidence that the T-allele associations seem to be age-dependent, with an increased risk reported for very-late-onset (after age 86) (Rodriguez-Rodriguez et al., 2009). Nonetheless, our observations may provide novel insights into genetic risks for pathological age-related cognitive impairment, specifically in females.

A potential limitation of our study is that it is not a GWAS. Although GWAS can characterize a much larger number of SNPs, it does not obviate the need for the candidate gene approach which can aid in further exploration of the biological and clinical interactions related to genetic risk and serve to validate GWAS findings, which are not hypothesis driven. We fully acknowledge that most of the SNPs associated in our study likely are not causative. This study includes a SNP selection based on a Caucasian reference, given that most of the sample was predominantly non-Hispanic white. Also, the control group of non-demented individuals was similar in age but not age-matched, which could affect the results. Given the adjustment for age at the data analysis stage, we believe the end effect to be similar. The limitations, however, should not undermine many unique aspects of the study, including the large number of extensively screened and characterized community-dwelling, older women with detailed prospective follow-up and relatively short intervals between assessments.

CONCLUSION

A number of GWAS investigations of AD have been conducted since the inception of this study and novel genes and their variants have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AD, which are currently beyond the scope of the current study. Follow-up studies are needed to address the newly identified risk genes. There is also a need for endophenotype strategies to further explore phenotypes related to dementia and age-related cognitive impairment. Candidate gene approaches may not only aid in the discovery of novel pathways involved in structural and functional brain aging, but also lead to better understanding of individual variations in brain structure and function.

Supplementary Material

Table 1: SNP Information.

Key Points:

A number of large-scale GWAS investigations of AD have been conducted and novel genes and their variants have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AD.

Candidate gene approaches may aid in the discovery of novel pathways involved in structural and functional brain aging.

Our findings may lead to a better understanding of the role these candidate genes play in cognition and cognitive impairment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

WHIMS was funded by the following: Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals; National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Contract No: HHSN-268–2004-6–4221C. WHIMS-ECHO was funded by the following: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Contract No: HHSN-268–2004-6–4221C; National Institute of Aging (NIA), Contract No. HHSN-271–2011-00004C. This study was also supported, in part, by the Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Aging, NIH and by K99AG032361 to Ira Driscoll.

REFERENCES

- Almeida OP, Schwab SG, Lautenschlager NT, Morar B, Greenop KR, Flicker L, Wildenauer D. KIBRA genetic polymorphism influences episodic memory in later life, but does not increase the risk of mild cognitive impairment. J Cell Mol Med 2008;12(5A):1672–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement 2017; 13:325–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric; Association (APA) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV [Internet] 4th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [cited 2010 Mar 8]. 866 p. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen OM, Reiche J, Schmidt V, et al. Neuronal sorting protein-related receptor sorLA/LR11 regulates processing of the amyloid precursor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102(38):13461–13466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annaert W, De Strooper A cell biological perspective on Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2002;18:25–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baquet ZC, Gorski JA, Jones KR. Early striatal dendrite deficits followed by neuron loss with advanced age in the absence of anterograde cortical brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurosci 2004;24:4250–4258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beecham GW, Hamilton K, Naj AC, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis of neuropathologic features of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. PLoS Genet 2014;10(9):e1004606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess JD, Pedraza O, Graff-Radford NR, et al. Association of common KIBRA variants with episodic memory and AD risk. Neurobiol Aging 2011;32(3):557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciottolo M, Wang X, Driscoll I, et al. Particulate air pollutants, APOE alleles and their contributions to cognitive impairment in older women and to amyloidogenesis in experimental models. Transl Psychiatry 2017;7(1):e1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedazo-Minguez A, Cowburn RF. Apolipoprotein E: a major piece in the Alzheimer’s disease puzzle. J Cell Mol Med 2001;5:254–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouraki V, Seshadri S. Genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Adv Genet 2014;87:245–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker LH, Espeland MA, Rapp SR,et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and cognitive outcomes: The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS). J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2010;118(4–5):304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science 1993;261:921–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneveaux JJ, Liang WS, Reiman EM, et al. Evidence for an association between KIBRA and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2010;31(6):901–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies G, Armstrong N, Bis JC, et al. Genetic contributions to variation in general cognitive function: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in the CHARGE consortium (N=53949). Mol Psychiatry 2015. February;20(2):183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA, DeCarlo CA, MacDonald SW, Vergote D, Jhamandas J, Westaway D. APOE and COMT polymorphisms are complementary biomarkers of status, stability, and transitions in normal aging and early mild cognitive impairment. Front Aging Neurosci 2014; 6:236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan MF, Goldberg TE, Kolachana BS, et al. Effect of COMT Val108/158 Met genotype on frontal lobe function and risk for schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98: 6917–6922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron M Deaths: Leading causes for 2014. National vital statistics reports 2016. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 65(5). [Google Scholar]

- Figurov A, Pozzo-Miller LD, Olafsson P, Wang T, Lu B. Regulation of synaptic responses to high-frequency stimulation and LTP by neurotrophins in the hippocampus. Nature 1996;381:706–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flirski M, Sobow T, Kloszewska I. Behavioural genetics of Alzheimer’s disease: a comprehensive review. Arch Med Sci 2011;7(2):195–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto N, Fujii T, Combarros O, et al. Sexually dimorphic effect of the Val66Met polymorphism of BDNF on susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease: New data and meta-analysis. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2010;153B(1):235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatt CE, Freimer NB. Association analysis of candidate genes for neuropsychiatric disease: the perpetual campaign. Trends Genet 2002;18:307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski JA, Zeiler SR, Tamowski S, Jones KR. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is required for the maintenance of cortical dendrites. J Neurosci 2003;23:6856–6865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goveas JS, Rapp SR, Hogan PE, et al. Predictors of Optimal Cognitive Aging in 80+ Women: The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016; 71 Suppl 1:S62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C, Liu X, Zhang F, et al. An updated meta-analysis of the association between SORL1 variants and the risk for sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2013;37(2):429–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun G, Vardarajan BN, Buros J, et al. Comprehensive search for Alzheimer disease susceptibility loci in the APOE region. Arch Neurol 2012;69(10):1270–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch CM, Goate AM. Alzheimer’s disease risk genes and mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. Biol Psychiatry 2015;77(1):43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe P, Wavrant-De Vrieze F, Crook R, et al. A full genome scan for late onset Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 1999;8:237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanni C, Garbin G, Lisa A, et al. Influence of COMT Val158Met polymorphism on Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in Italian patients. J Alzheimers Dis 2012;32(4):919–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Everitt BJ, Thomas KL. Independent cellular processes for hippocampal memory consolidation and reconsolidation. Science 2004;304:839–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WY, Wu BT, Lee CC, et al. Association analysis of dopaminergic gene variants (Comt, Drd4 And Dat1) with Alzheimer s disease. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2012;26(3):401–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1989;39:1159–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozhui K, Snively BM, Rapp SR, Wallace RB, Williams RW, Johnson KC. Genetic Analysis of Mitochondrial Ribosomal Proteins and Cognitive Aging in Postmenopausal Women. Front Genet 2017;8:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donoghue MC, Murphy SE, Zamboni G, Nobre AC, Mackay CE. APOE genotype and cognition in healthy individuals at risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A review. Cortex 2018;104:103–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papassotiropoulos A, Stephan DA, Huentelman MJ, et al. Common Kibra alleles are associated with human memory performance. Science 2006;314:475–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira PA, Romano-Silva MA, Bicalho MA, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase genetic variant associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in a Brazilian population. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2012;34(2):90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkovic MN, Strac DS, Tudor L, Konjevod M, Erjavec GN, Pivac N. Catechol-O-methyltransferase, Cognition and Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2018; 15(5):408–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2001;58(12):1985–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz C, Mayeux R. Use of genetic variation as biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009;1180:75–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SM, Coker LH, Maki PM, Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Shumaker SA. The Women’s Health Initiative Study of Cognitive Aging (WHISCA): a randomized clinical trial of the effects of hormone therapy on age-associated cognitive decline. Clin Trials 2004;1(5):440–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SM, Espeland MA, Jaramillo SA, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and regional brain volumes: the WHIMS-MRI Study. Neurology 2009;72(2):135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Rodriguez E, Infante J, Llorca J, et al. Age-dependent association of KIBRA genetic variation and Alzheimer’s disease risk. Neurobiol Aging 2009;30:322–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogaeva E, Meng Y, Lee JH, Gu Y, et al. The neuronal sortilin-related receptor SORL1 is genetically associated with Alzheimer disease. Nat Genet 2007;39(2):168–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roses AD, Lutz MW, Amrine-Madsen H, et al. A TOMM40 variable-length polymorphism predicts the age of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacogenomics J 2010;10(5):3753–3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaper K, Kolsch H, Popp J, Wagner M, Jessen F. KIBRA gene variants are associated with episodic memory in healthy elderly. Neurobiol Aging 2008;29(7):1123–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serretti A, Olgiati P. Catechol-o-methyltransferase and Alzheimer’s disease: a review of biological and genetic findings. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2012;11(3):299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker SA, Reboussin BA, Espeland MA, et al. The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS): a trial of the effect of estrogen therapy in preventing and slowing the progression of dementia. Control Clin Trials 1998;19(6):604–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry 1987;48(8):314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster JA, Myers AJ, Pearson JV, et al. Sorl1 as an Alzheimer’s disease predisposition gene? Neurodegener Dis 2008;5:60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table 1: SNP Information.