Abstract

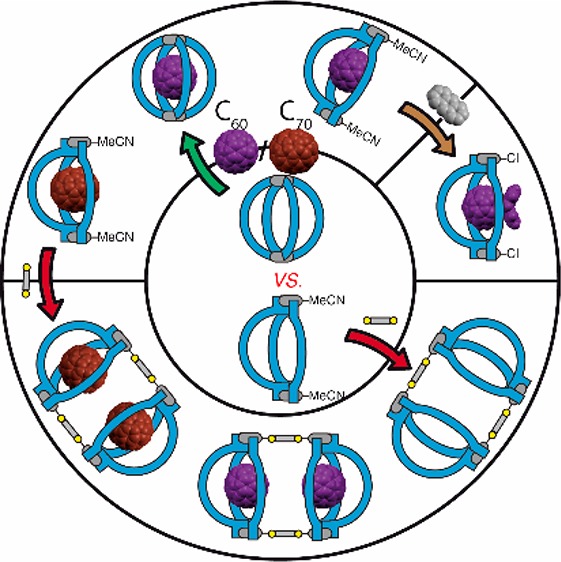

Fullerenes and their derivatives are of tremendous technological relevance. Synthetic access and application are still hampered by tedious purification protocols, peculiar solubility, and limited control over regioselective derivatization. We present a modular self-assembly system based on a new low-molecular-weight binding motif, appended by two palladium(II)-coordinating units of different steric demands, to either form a [Pd2L14]4+ cage or an unprecedented [Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ bowl (with L1 = pyridyl, L2 = quinolinyl donors). The former was used as a selective induced-fit receptor for C60. The latter, owing to its more open structure, also allows binding of C70 and fullerene derivatives. By exposing only a fraction of the bound guests’ surface, the bowl acts as fullerene protecting group to control functionalization, as demonstrated by exclusive monoaddition of anthracene. In a hierarchical manner, sterically low-demanding dicarboxylates were found to bridge pairs of bowls into pill-shaped dimers, able to host two fullerenes. The hosts allow transferring bound fullerenes into a variety of organic solvents, extending the scope of possible derivatization and processing methodologies.

Introduction

As stable carbon allotropes, fullerenes feature curved, fully π-conjugated surfaces with unique electronic properties that render them highly versatile for application in functional materials.1 Established techniques for the separation of industrial fullerene mixtures are based on sublimation, crystallization, extraction, and chromatographic protocols.2 The scope of solution processing methods, e.g., for controlled derivatization, preparation of composite materials, surface deposition, and device fabrication, is still limited due to the small choice of suitable aromatic and halogenated solvents.

Within the field of supramolecular chemistry, large efforts have been devoted to the construction of fullerene receptors aimed at facilitating selective purification and derivatization methods.3 In this regard, covalent organic tweezers and macrocycles based on extended aromatic panels, such as calixarenes, porphyrins and extended tetrathiafulvalenes, fully conjugated belts, as well as curved architectures such as triptycenes, have been intensively studied.4 As most of these host compounds are the result of lengthy syntheses, self-assembled fullerene binders composed of much simpler building blocks have moved into focus, recently. Among those, metal-mediated rings and cages are notably versatile, owing to their modular composition and tunable cavity. Examples include Yoshizawa’s anthracene-lined [M2L4]4+ cages,5 Nitschke’s tetrahedral aromatic-paneled arrangement,6 cubic porphyrin boxes,3a,7 and Ribas’ heteroleptic prismatic cage.3c,8

Common to most previously reported metal-mediated fullerene receptors3b is their rather high molecular weight, as a result of maximizing the offered π-surface area. We were therefore interested in designing a new metallo-supramolecular receptor based on the well-studied [Pd2L4]4+ coordination cage motif,9 that is (1) of lower molecular weight than existing hosts, (2) straightforward to synthesize and derivatize, and (3) capable of discriminating different fullerenes and dissolving them in a range of organic solvents. On the basis of computer-aided modeling, we further aimed at finding a perfect structural match between a curved binding motif, the connective metal complex, and the spherical C60 fullerene. Our design is based on a curved dibenzo-2.2.2-bicyclo-octane backbone reminiscent of triptycene10 but lacking the third benzene ring that is not in touch with the fullerene guest (Figure 1a and Figure S117).

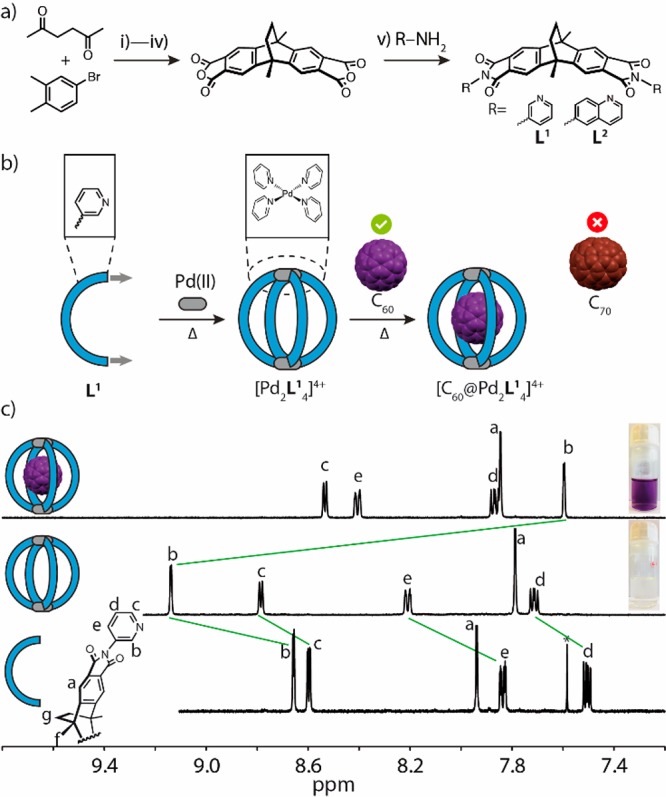

Figure 1.

Ligand and cage synthesis. (a) Preparation of ligands L1 and L2: (i) Mg, THF; (ii) AlCl3, toluene; (iii) KMnO4, pyridine/H2O; (iv) Ac2O; (v) for L1: 3-aminopyridine, 165 °C, 10 min; for L2: 6-aminoquinoline, 165 °C, 10 min. (b) Ligand L1 assembles with PdII cations to cage [Pd2L14]4+ capable of selectively binding C60. (c) 1H NMR spectra (600 MHz, 298 K, CD3CN) of Ligand L1 (2.56 mM), cage [Pd2L14]4+ (0.64 mM), host–guest complex [C60@Pd2L14]4+ (0.64 mM) obtained from mixing free cage [Pd2L14]4+ with pure C60 at 70 °C (from bottom to top).

We introduced phthalimide-based joints to pyridines, that coordinate to Pd(II) cations, thereby bringing all four ligands into perfect relative distances to be able to encapsulate C60 fullerene. Indeed, the as-planned host performed excellently as a fullerene host, and initial concerns that a receptor containing eight phthalimide units would become too electron-deficient to bind C60 did not materialize. In addition, ligand derivatization with sterically more demanding quinoline donors yielded an unprecedented [Pd2L23X2]n+ bowl structure (X = CH3CN or Cl–), which allowed us to extend the guest scope to C70 and use it as a fullerene-protecting group in cycloaddition reactions with anthracene. The bowl’s sterically congested coordination environment allows clean conversion into a heteroleptic assembly11 via hierarchical reaction with bridging carboxylates,8c,12 thus yielding a pill-shaped dimer, capable of binding two fullerenes.13 All findings are supported by NMR and mass spectrometric results as well as single crystal X-ray structures of one ligand, both empty hosts, and three different host–guest complexes, achieved with a combination of cryogenic crystal handling, the use of highly brilliant synchrotron radiation,14 and advanced macromolecular refinement protocols.

Results and Discussion

Ligand Synthesis, Cage Assembly, Fullerene Binding

Backbone dianhydride, depicted in Figure 1a, was prepared in four steps starting from 4-bromo-1,2-dimethylbenzene and 2,5-hexanedione according to a reported procedure.15 Straightforward conversion into ligands L1 and L2 was achieved by reaction with 3-aminopyridine and 6-aminoquinoline, respectively. Likewise to other banana-shaped, bis-monodentate pyridyl ligands reported previously, heating a 2:1 mixture of L1 and [Pd(MeCN)4](BF4)2 in deuterated acetonitrile at 70 °C for 1 d resulted in the quantitative formation of cage [Pd2L14]4+, unambiguously characterized by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure 1b and c), mass spectrometry (Figure S8), and a single crystal X-ray structure (Figure 4a). The 1H NMR spectrum reveals that the proton signals of the pyridine moieties undergo a downfield shift associated with metal complexation. Encapsulation of C60 and C70 were tested by stirring acetonitrile solutions of the cage over the solid fullerenes (usually adding an excess of finely ground material, while about 1.2 equiv were found to be sufficient). Intriguingly, [Pd2L14]4+ is only able to encapsulate C60, but not C70, which we attribute to the good match in terms of shape (spherical C60 vs ellipsoidal C70) and size (572 Å3 void space; Figure S114; vs 547 Å3 van-der-Waals volume of C60, 646 Å3 of C70)16 for the tailor-made cavity. Upon absorbing C60 inside the cage, the 1H NMR signal of inward-pointing proton Hb undergoes an upfield-shift of 1.54 ppm, along with a color change of the solution from colorless to purple (Figure 1c). Further indication of C60 binding was observed in the UV–vis and high-resolution ESI mass spectra (Figure S12 and S104). Upon binding C60, the acetonitrile solution of [C60@Pd2L14]4+ showed a broad absorption band around λmax= 339 nm. Besides acetonitrile, also other solvents such as acetone, nitromethane, and DMF could be used to dissolve the cage and the host–guest complex (Figure S81–S89).

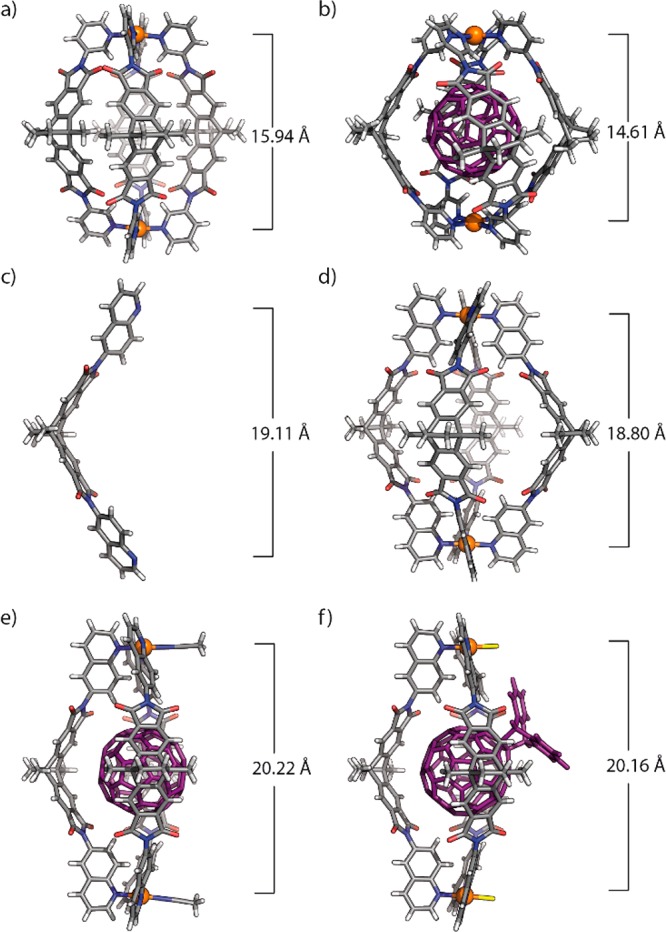

Figure 4.

X-ray crystal structures. (a) [Pd2L14]4+, (b) [C60@Pd2L14]4+, (c) L2, (d) [Pd2L24]4+, (e) [C60@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+, and (f) [C60Ac@Pd2L23Cl2]2+. Solvent molecules, anions, guest disorder and outside of cage and bowl structures are omitted for clarity (PdII, orange; C, gray; N, blue; O, red; Cl, yellow; H, white; C60 and C60Ac, purple).

Diffusion of isopropyl ether into the acetonitrile solution of [C60@Pd2L14](BF4)4 allowed us to grow single crystals in the form of red plates, suitable for synchrotron X-ray diffraction analysis. Three crystallographically independent host–guest complexes were found in the asymmetric unit, all showing the same C60-occupied cage [C60@Pd2L14]4+ with the C60 guest disordered over two positions, but featuring slightly different Pd–Pd distances (14.66, 14.61, and 14.55 Å, respectively) due to a certain degree of backbone flexibility and crystal packing effects (see Figure 4b and S108). The average distance from the ligand benzene ring centroids to the center of C60 is 6.72 Å (3.56–3.88 Å to the six/five membered rings of C60, see Table S8), verifying that the precisely designed concave inner surface can serve as fullerene receptor through strong π–π interactions. Similar distances were reported for C60 receptors based on other aromatic systems.17 The average distance from pyridine hydrogen Hb to the C60 centroid is 6.11 Å (2.76–3.29 Å to the six/five membered rings of C60, see Table S8), further indicating significant contribution from CH−π interactions. Colorless, block-shaped crystals could be grown when tetrahydrofuran (THF) was diffused into the acetonitrile solution of [C60@Pd2L14](BF4)4. X-ray analysis revealed a [Pd2L14]4+ cage, not containing any fullerenes, but two BF4– counteranions (Figure 4a and S107). The D4h-symmetric cage shows a Pd–Pd distance of 15.94 Å. When comparing the geometries of the BF4–-containing cage [Pd2L14]4+ with the host–guest complex [C60@Pd2L14]4+ it turns out that fullerene binding leads to an averaged Pd–Pd distance shortening of 1.3 Å. This goes along with a twist of all four ligands in a helical manner around the encapsulated C60. As a result, the dihedral angle between two pyridine arms of the same ligand is 62.3° (Figure S108), whereas the corresponding dihedral angle in the free cage [Pd2L14]4+ is only 1.0°. Hence, uptake of C60 leads to a conformational change of the cage geometry indicating an induced-fit structural adaptation to perfectly accommodate C60 within the cavity.3c,18

Self-Assembly of Bowls and Guest Uptake

The initial aim of synthesizing quinoline-modified ligand L2, featuring a larger N–N distance than found in L1, was to enlarge the cavity size, thus allowing to accommodate larger guests inside the cage. To our surprise, prolonged heating of a 2:1 mixture of ligand L2 and [Pd(MeCN)4](BF4)2 in deuterated acetonitrile yielded the expected [Pd2L24]4+ cage only as a minor product, accompanied by a 4-fold excess of a new species whose peculiar 1H NMR signal pattern as well as unambiguous mass spectral features allowed us to assign it to bowl-shaped compound [Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+, explainable as a [Pd2L24] cage lacking the fourth ligand (Figure S19 and S22). Previous work on Pd-mediated assembly with banana-shaped bis-monodentate pyridyl ligands never reported such bowl species (however, few reports exist for sterically more demanding ligand systems).19 Closer inspection of the steric situation around the metal coordination sites suggested that the quinolines’ hydrogen atoms (Hc) adjacent to the coordinating nitrogen atoms seem to cause significant steric crowding. This hypothesis was indeed supported by the observation that reacting ligand L2 with [Pd(MeCN)4](BF4)2 in a 3:2 ratio at room temperature yielded [Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ as a single product after 2 days. Further proof for the suggested bowl geometry came from characteristic cross peaks in the sample’s 1H–1H NOESY NMR spectrum (Figure S15), the quinoline moieties’ 1H signal splitting into two sets with 2:1 integral ratio and the observation of prominent peaks in the ESI mass spectrum consistent with the formula [Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+, alongside further adducts with various anions [Pd2L23(MeCN) + X]3+ (X = F–, Cl–, BF4–). Surprisingly, slow vapor diffusion of isopropyl ether into a MeCN solution of bowl [Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ produced single crystals for which a synchrotron-based diffraction experiment revealed the structure of cage [Pd2L24]4+ (Figure 4d), indicating the fine energetic balance between these two species.

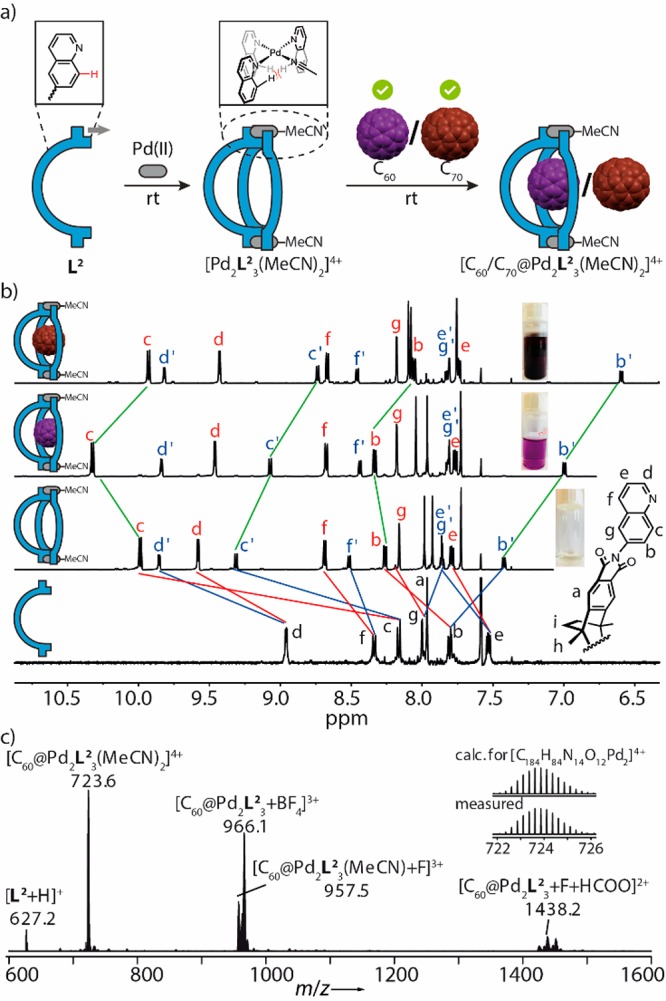

Owing to the bowl’s open geometry, we found [Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ to be able to bind both C60 to give [C60@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ and C70 to yield [C70@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ in a quantitative manner, both accompanied by characteristic color changes. In a competitive binding experiment, exposing bowl [Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ to an equimolar mixture of powdered C60/C70 (5 equiv/5 equiv), preferred binding of C70 was observed (ratio of [C70@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ to [C60@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ ≈ 4:1; Figure S78). The UV–vis spectrum of [C60@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ in acetonitrile showed a shoulder ranging from 330 to 420 nm compared to empty bowl [Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+, whereas [C70@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ displayed enhanced absorption in the longer wavelength region with one band around λmax= 383 and a broad band around 473 nm (Figure S105). Interestingly, the herein observed spectral features of fullerenes bound to a rather electron-deficient host differ significantly from Yosizawa’s recent report on binding the same fullerenes to electron-rich anthracene-based hosts in the same solvent.5b In the 1H NMR spectra of the host–guest complexes, protons Hb, Hb′, Hc, and Hc′, located inward from the coordination sites, show distinct shifts upon binding of the fullerenes within the bowl (Figure 2b). ESI mass spectrometry unambiguously supported the formation of the 1:1 host–guest complexes, while partial substitution of the acetonitrile ligands by trace amounts of anions was observed (Figure 2c). Consequently, we titrated 2 equiv of a solution of tetrabutylammonium chloride into a solution of bowl [Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+, which afforded a quantitative conversion into compound [Pd2L23Cl2]2+. Likewise, the fullerene carrying complexes could be converted into chloride-coordinated species, thus giving rise to very clean NMR and mass spectral results (Figure S42 and S45). We evaluated the thermal stability of the different bowl species in solution and found that [Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ and [C70@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ partly converted into [Pd2L24]4+ and [C70@Pd2L24]4+, respectively, upon prolonged heating at 70 °C, whereas [C60@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ remained unchanged under these conditions (Figure S18, S29 and S36).

Figure 2.

Self-assembly and characterization of bowl compounds. (a) L2, comprising sterically demanding quinoline donors, reacts with PdII to the bowl-shaped host, which binds both C60 and C70. (b) 1H NMR spectra of ligand L2 (600 MHz, 298 K, CD3CN), bowl [Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+, [C60@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+, [C70@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ (all 0.64 mM, 298 K, CD3CN) and photos of solutions. Red and blue marked proton signals are assigned to edge and central ligands, respectively. (c) High resolution ESI mass spectrum of [C60@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+, prepared in pure CH3CN.

We were able to obtain the single crystal X-ray structures of ligand L2, cage [Pd2L24]4+, and host–guest complex [C60@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ (Figure 4c–e), thus allowing us to compare structural features between L2 in its free form, as part of the cage as well as the bowl geometry. In case of the free ligand and cage [Pd2L24]4+, angles between the backbone’s benzene planes are 119.8° and 120.2°, respectively, while slight widening (123.9°) was observed in case of the bowl. Likewise, the ligands’ N–N distance of 19.11 Å for free L2 and Pd–Pd distance of 18.80 Å for cage [Pd2L24]4+ compared to 20.22 Å for bowl [C60@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ indicate a slight opening of the cavity when the fourth ligand is missing. Of particular interest is comparing the immediate ligand environment around the PdII cations in the cage and bowl structures: as expected, the quinoline Hc hydrogen substituents lead to significant steric crowding in case of cage [Pd2L24]4+, where four protons have to squeeze in the small space under the coordinated metal cation, leading to an average H–H distances of 2.31 Å (less than double the van-der-Waals radius of hydrogen, 1.2 Å) and a small deviation of the PdII-coordination geometry from planarity with N–Pd–N angles of 176°.19 Even more compelling is the situation in the quinoline-based bowl [C60@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+: here, the Hc′ hydrogen substituent belonging to the central ligand pushes both Hc hydrogens of adjacent quinolines aside in direction of the lean acetonitrile ligand, giving rise to H–H distances of 2.56, 2.50, and 2.47 Å. In this bowl structure, the average distance from the ligand benzene ring centroids to the center of C60 is 6.79 Å (3.67–3.93 Å to the six/five membered rings of C60, see Table S14), and the average distance from quinoline Hb hydrogens to the C60 centroid is 6.39 Å (2.92–3.53 Å to the six/five membered rings of C60, Table S14), which are all slightly longer than the corresponding distances in [C60@Pd2L14]4+, still indicating both π–π and CH−π interactions between C60 and the bowl.

Bowl-Protected Diels–Alder Reaction of C60 with Anthracene (Ac)

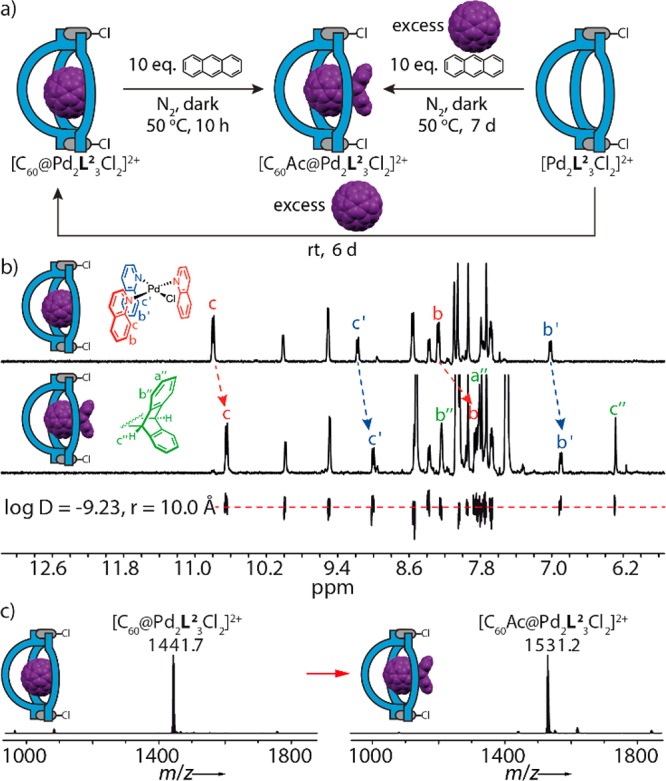

As observed in the crystal structure of [C60@Pd2L23(MeCN)2](BF4)4 (Figure 4e), most of the C60 surface is covered by the bowl geometry, while exposing only a patch measuring about 25% of the total surface area to the acetonitrile solution environment. In order to elucidate whether the bowl-shaped host can modulate the fullerene’s chemical reactivity, we subjected complex [C60@Pd2L23Cl2]2+ (featuring chloride instead of acetonitrile ligands) to a Diels–Alder reaction with anthracene. The same reaction had been studied before within a cubic coordination cage and a metal–organic-framework, both leading to formation of the bis-adduct.3a,20 With pure C60, this reaction requires the use of problematic solvents such as benzene, chlorinated aromatics or CS2 and is known to deliver mixtures of mono-, di-, or even triadducts.21 Our system, on the other hand, allows the smooth conversion into the anthracene monoadduct (90% yield) when a MeCN solution of [C60@Pd2L23Cl2]2+ (0.56 mM, 1 equiv) is treated with up to 10 equiv of anthracene at 50 °C in the dark under a nitrogen atmosphere for about 12 h (equilibrium constant K323 = 2210 L mol–1) (Figure S99 and Table S1).

The 1H NMR spectrum of the reaction product shows upfield shifts of bowl protons Hb, Hb′, Hc, Hc′. DOSY NMR analysis reveals that both the guest’s and host’s 1H NMR signals belong to a single species with a hydrodynamic radius of about 10.0 Å. The ESI mass spectrum shows a single peak for the expected [C60Ac@Pd2L23Cl2]2+ ion (Figure 3b and 3c). We were further able to obtain single crystals of [C60Ac@Pd2L23Cl2](BF4)2 (Figure 4f), thereby delivering the first X-ray crystallographic report of the C60-anthracene monoadduct structure, which is a light- and oxygen-sensitive compound in solution. The structure reveals that no second anthracene molecule would be able to add to the encapsulated guest for steric reasons. Interestingly, unlike the disordered C60 guests in the other structures, substituted fullerene C60Ac could be refined without geometrical restraints and did not require modeling of a second conformer. The fused substituent is not positioned in the middle of the window of the bowl structure, but rather tilted to one side (presumably for maximizing a stabilizing CH–O contact measuring 2.2 Å between one of the guest’s bridgehead protons and a ligand oxygen). Since no signal splitting is observed in the 1H NMR spectrum of the host–guest complex that would point to such a fixed, unsymmetrical conformation existing in solution, we expect the system to show a dynamic behavior comparable to a ball-and-socket joint.

Figure 3.

Diels–Alder reaction between C60 and anthracene within the host–guest complex [C60@Pd2L23Cl2]2+. (a) Stepwise or one-pot access to the encapsulated monoadduct. (b) Comparison of 1H NMR spectra (500 MHz, 298 K, CD3CN) of [C60@Pd2L23Cl2]2+ (0.56 mM) and [C60Ac@Pd2L23Cl2]2+ (0.36 mM), DOSY trace showing all aromatic signals of [C60Ac@Pd2L23Cl2]2+ having the same diffusion coefficient. (c) ESI high resolution mass spectra of [C60@Pd2L23Cl2]2+ and [C60Ac@Pd2L23Cl2]2+.

Dimerization of Bowls to Give Difullerene Complexes

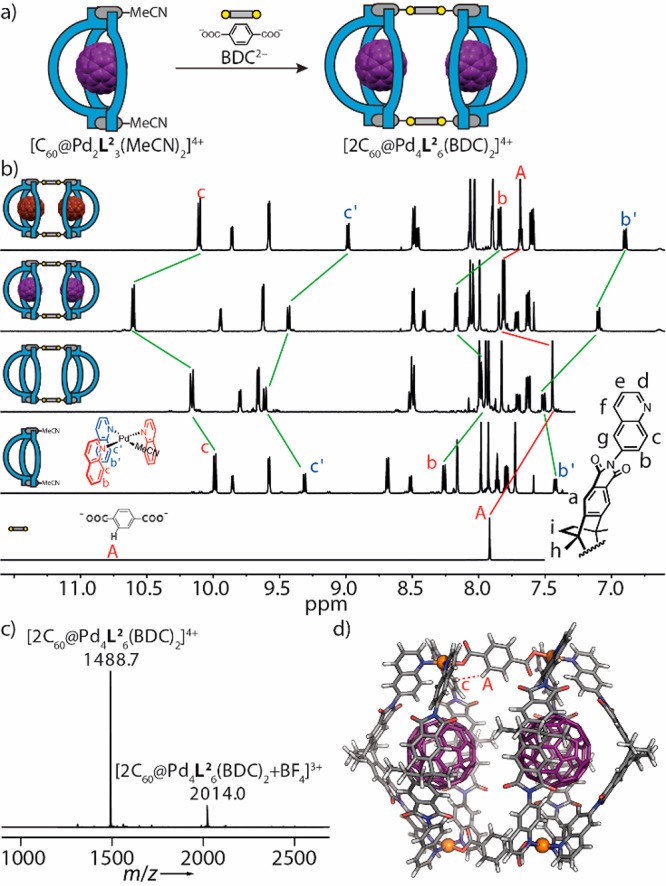

With the X-ray structures of bowls [C60@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ and [C60Ac@Pd2L23Cl2]2+ in hand, carrying acetonitrile and chloride ligands, respectively, to complement the Pd(II) square-planar coordination environments, the question arose whether other, sterically low-demanding donors could be installed in this position as well. Comparable to Stang’s methodology of mixing N-donor with carboxylate ligands,12 we succeeded in substituting both of the bowl’s acetonitriles with carboxylate anions. Most interestingly, this allowed us to cleanly dimerize two bowls into pill-shaped assemblies using two terephthalate bridges (BDC, Figure 5). Dimerization could be shown for the empty bowl and its C60 as well as C70 complexes, as unambiguously demonstrated by NMR, UV–vis spectra, and ESI MS results.

Figure 5.

Hierarchical assembly and characterization of pill-shaped dimers. (a) Bowl [C60@Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ reacts with terephthalate (BDC2–) to form dimer [2C60@Pd4L26(BDC)2]4+. (b) 1H NMR spectra (600 MHz, 298 K, CD3CN) of BDC2– (15 mM), [Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ (0.64 mM), [Pd4L26(BDC)2]4+ (0.31 mM), [2C60@Pd4L26(BDC)2]4+ (0.31 mM), and [2C70@Pd4L26(BDC)2]4+ (0.31 mM) (from bottom to top). Red and blue marked proton signals are assigned to edge and central ligands in the bowl geometries, respectively. (c) High-resolution ESI mass spectrum of [2C60@Pd4L26(BDC)2]4+. (d) PM6-optimized structure of [2C60@Pd4L26(BDC)2]4+.

The 1H NMR spectrum of the guest-free dimer shows the 2:1 signal splitting for the quinoline moieties retained and a single signal for the four protons of the phenylene bridge, indicating the formation of a single product containing the terephthalates symmetrically joining two identical halves. The dimer binds two fullerenes (C60 or C70) without experiencing any further symmetry-related signal splitting effects. Encapsulation-induced chemical shift changes are analogous to what was observed for the monomeric bowls (compare Figures 2b and 5b). Further, taking C60-occupied dimer [2C60@Pd4L26(BDC)2]4+ as an example, the NOE NMR spectrum reveals a contact between signals Hc of the flanking quinolines (but not Hc′ of the central one) and the terephthalate proton HA, in accordance with the relatively short distance between these atoms observed in the PM6-optimized structure (Figure 5d and Figure S60). Furthermore, the increase in size from monomeric bowl to the pill-shaped dimer was confirmed by DOSY experiments, giving diffusion coefficients of 5.20 × 10–10 m2 s–1 for the monomer (Figure S27) and 4.08 × 10–10 m2 s–1 for the dimer (Figure S62). Comparison of UV–vis spectra of empty and fullerene-filled dimers shows very similar absorption bands compared to the monomeric bowl system, further confirming the binding of fullerenes within the inner cavities (Figure S106). The high-resolution ESI mass spectrum of the dimer revealed prominent signals at m/z 1488.7 and 2014.0, consistent with the simulated isotopic pattern of formulas [2C60@Pd4L26(BDC)2 + nBF4](4–n)+ (n = 0, 1) (Figure 5c). Analogous NMR and MS results were also obtained for the guest-free (Figure S53–57) and (C70)2-containing (Figure S64–69) dimers, showing that guest encapsulation is orthogonal to the dimerization process.

Conclusions

On the basis of a rational design approach, we synthesized new self-assembled, low-weight fullerene receptors that allow the solution handling and facile crystallization of fullerenes as well as their adducts. The first receptor, consisting of pyridyl-terminated, bent ligands assembling with PdII cations to a [Pd2L14]4+ cage, is highly selective for C60. The second receptor was assembled using quinoline donors, which—owing to their steric demand—led to an unprecedented [Pd2L23(MeCN)2]4+ bowl geometry. This bowl not only was found to display a wider guest encapsulation scope (including C70), but also is capable of serving as a supramolecular protecting group, allowing selective monofunctionalization of its fullerene guest. We further show that these bowls, both with and without bound fullerenes, can be cleanly dimerized by exchanging the acetonitrile ligands for terephthalate bridges, giving large, pill-shaped architectures of heteroleptic nature. The herein introduced receptors have the potential to serve as new tools for handling fullerenes and their derivatives in a wider range of organic solvents, and further allow their selective uptake and regioselective modification. Applications related to advanced fullerene derivatization, purification, structure elucidation, and device fabrication are sought to benefit from our findings.

Acknowledgments

B.C. thanks the China Scholarship Council for a PhD fellowship. S.H. thanks the JSPS program for Advancing Strategic International Networks to Accelerate the Circulation of Talented Researchers. We thank the European Research Council (ERC Consolidator grant 683083, RAMSES) and the DFG (RESOLV Cluster of Excellence EXC 2033, project number 390677874, and GRK2376 “Confinement-controlled Chemistry”, project number 331085229) for support. We thank Christiane Heitbrink and Laura Schneider for measuring ESI mass spectra and André Platzek for measuring DOSY spectra. Diffraction data of [Pd2L14](BF4)4, [C60@Pd2L14](BF4)4, [Pd2L24](BF4)4, and [C60Ac@Pd2L23Cl2](BF4)2 was collected at PETRA III, DESY, a member of the Helmholtz Association (HGF). We thank Saravanan Panneerselvam, Sebastian Guenther, and Eva Crosas for assistance in using synchrotron beamline P11 (I-20170404 and I-20170714).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.9b02207.

Experimental details and further NMR, MS, UV–vis and crystal data (PDF)

Crystal data for [C60Ac@Pd2L23Cl2], CCDC 1858158 (CIF)

Crystal data for [C60@Pd2L23(MeCN)2], CCDC 1850362 (CIF)

Crystal data for [Pd2L24], CCDC 1850361 (CIF)

Crystal data for L2, CCDC 1850360 (CIF)

Crystal data for [C60@Pd2L14], CCDC 1850359 (CIF)

Crystal data for [Pd2L14], CCDC 1850358 (CIF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Langa F.; Nierengarten J.-F.. Fullerenes: Principles and Applications, 2nd ed.; RSC: Cambridge, 2011; pp 191–328. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch A.; Brettreich M.. Fullerenes: Chemistry and Reactions; VCH: Weinheim, 2005; pp 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- a Brenner W.; Ronson T. K.; Nitschke J. R. Separation and selective formation of fullerene adducts within an MII8L6 cage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 75–78. 10.1021/jacs.6b11523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b García-Simón C.; Costas M.; Ribas X. Metallosupramolecular receptors for fullerene binding and release. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 40–62. 10.1039/C5CS00315F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c García-Simón C.; Monferrer A.; Garcia-Borràs M.; Imaz I.; Maspoch D.; Costas M.; Ribas X. Size-selective encapsulation of C60 and C60-derivatives within an adaptable naphthalene-based tetragonal prismatic supramolecular nanocapsule. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 798–801. 10.1039/C8CC07886F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Han W. K.; Zhang H. X.; Wang Y.; Liu W.; Yan X.; Li T.; Gu Z. G. Tetrahedral metal-organic cages with cube-like cavities for selective encapsulation of fullerene guests and their spin-crossover properties. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 12646–12649. 10.1039/C8CC06652C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Martínez-Agramunt V.; Eder T.; Darmandeh H.; Guisado-Barrios G.; Peris E. A Size-Flexible Organometallic Box for the Encapsulation of Fullerenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 2019 (58), 5682–5686. 10.1002/anie.201901586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Suzuki K.; Takao K.; Sato S.; Fujita M. Coronene nanophase within coordination spheres: increased solubility of C60. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2544–2545. 10.1021/ja910836h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Mahata K.; Frischmann P. D.; Würthner F. Giant electroactive M4L6 tetrahedral host self-assembled with Fe(II) vertices and perylenebisimide dye edges. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 15656–15661. 10.1021/ja4083039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Rizzuto F. J.; Nitschke J. R. Stereochemical plasticity modulates cooperative binding in a CoII12L6 cuboctahedron. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 903–908. 10.1038/nchem.2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Kawano S. I.; Fukushima T.; Tanaka K. Specific and oriented encapsulation of fullerene C70 into a supramolecular double-decker cage composed of shape-persistent macrocycles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 14827–14831. 10.1002/anie.201809167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Fuertes-Espinosa C.; Gómez-Torres A.; Morales-Martínez R.; Rodríguez-Fortea A.; García-Simón C.; Gandara F.; Imaz I.; Juanhuix J.; Maspoch D.; Poblet J. M.; Echegoyen L.; Ribas X. Purification of uranium-based endohedral metallofullerenes (EMFs) by selective supramolecular encapsulation and release. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 11294–11299. 10.1002/anie.201806140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Ikeda A.; Yoshimura M.; Udzu H.; Fukuhara C.; Shinkai S. Inclusion of [60]fullerene in a homooxacalix[3]arene-based dimeric capsule cross-linked by a PdII-pyridine interaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 4296–4297. 10.1021/ja984396e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; l Sánchez-Molina I.; Grimm B.; Krick Calderon R. M.; Claessens C. G.; Guldi D. M.; Torres T. Self-assembly, host-guest chemistry, and photophysical properties of subphthalocyanine-based metallosupramolecular capsules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 10503–10511. 10.1021/ja404234n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m Nakamura T.; Ube H.; Miyake R.; Shionoya M. A C60-templated tetrameric porphyrin barrel complex via zinc-mediated self-assembly utilizing labile capping ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18790–18793. 10.1021/ja4110446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a AbeyratneKuragama P. L.; Fronczek F. R.; Sygula A. Bis-corannulene receptors for fullerenes based on Klarner’s tethers: reaching the affinity limits. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5292–5295. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Atwood J. L.; Koutsantonis G. A.; Raston C. L. Purification of C60 and C70 by selective complexation with calixarenes. Nature 1994, 368, 229–231. 10.1038/368229a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Canevet D.; Pérez E. M.; Martín N. Wraparound hosts for fullerenes: tailored macrocycles and cages. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9248–9259. 10.1002/anie.201101297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Kawase T.; Kurata H. Ball-, bowl-, and belt-shaped conjugated systems and their complexing abilities: exploration of the concave-convex π-π interaction. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 5250–5273. 10.1021/cr0509657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Yang Y.; Cheng K.; Lu Y.; Ma D.; Shi D.; Sun Y.; Yang M.; Li J.; Wei J. A polyaromatic nano-nest for hosting fullerenes C60 and C70. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 2138–2142. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kishi N.; Li Z.; Yoza K.; Akita M.; Yoshizawa M. An M2L4 molecular capsule with an anthracene shell: encapsulation of large guests up to 1 nm. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 11438–11441. 10.1021/ja2037029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kishi N.; Akita M.; Yoshizawa M. Selective host-guest interactions of a transformable coordination capsule/tube with fullerenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 3604–3607. 10.1002/anie.201311251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ronson T. K.; League A. B.; Gagliardi L.; Cramer C. J.; Nitschke J. R. Pyrene-edged FeII4L6 cages adaptively reconfigure during guest binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 15615–15624. 10.1021/ja507617h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ronson T. K.; Meng W.; Nitschke J. R. Design principles for the optimization of guest binding in aromatic-paneled FeII4L6 cages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9698–9707. 10.1021/jacs.7b05202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng W.; Breiner B.; Rissanen K.; Thoburn J. D.; Clegg J. K.; Nitschke J. R. A self-assembled M8L6 cubic cage that selectively encapsulates large aromatic guests. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 3479–3483. 10.1002/anie.201100193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Colomban C.; Szalóki G.; Allain M.; Gómez L.; Goeb S.; Sallé M.; Costas M.; Ribas X. Reversible C60 ejection from a metallocage through the redox-dependent binding of a competitive guest. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 3016–3022. 10.1002/chem.201700273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fuertes-Espinosa C.; García-Simón C.; Castro E.; Costas M.; Echegoyen L.; Ribas X. A copper-based supramolecular nanocapsule that enables straightforward purification of Sc3N-based endohedral metallofullerene soots. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 3553–3557. 10.1002/chem.201700046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c García-Simón C.; Garcia-Borràs M.; Gómez L.; Parella T.; Osuna S.; Juanhuix J.; Imaz I.; Maspoch D.; Costas M.; Ribas X. Sponge-like molecular cage for purification of fullerenes. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5557. 10.1038/ncomms6557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Clever G. H.; Punt P. Cation-anion arrangement patterns in self-assembled Pd2L4 and Pd4L8 coordination cages. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2233–2243. 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jansze S. M.; Wise M. D.; Vologzhanina A. V.; Scopelliti R.; Severin K. PdII2L4-type coordination cages up to three nanometers in size. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 1901–1908. 10.1039/C6SC04732G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Lewis J. E. M.; Gavey E. L.; Cameron S. A.; Crowley J. D. Stimuli-responsive Pd2L4 metallosupramolecular cages: towards targeted cisplatin drug delivery. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 778–784. 10.1039/C2SC00899H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Chen C. F.; Han Y. Triptycene-derived macrocyclic arenes: from calixarenes to helicarenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2093–2106. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mastalerz M. Porous shape-persistent organic cage compounds of different size, geometry, and function. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2411–2422. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Xie T. Z.; Guo K.; Guo Z.; Gao W. Y.; Wojtas L.; Ning G. H.; Huang M.; Lu X.; Li J. Y.; Liao S. Y.; Chen Y. S.; Moorefield C. N.; Saunders M. J.; Cheng S. Z.; Wesdemiotis C.; Newkome G. R. Precise molecular fission and fusion: quantitative self-assembly and chemistry of a metallo-cuboctahedron. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 9224–9229. 10.1002/anie.201503609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullen S.; Clever G. H. Mixed-ligand metal-organic frameworks and heteroleptic coordination cages as multifunctional scaffolds-a comparison. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 3052–3064. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cook T. R.; Stang P. J. Recent developments in the preparation and chemistry of metallacycles and metallacages via coordination. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7001–7045. 10.1021/cr5005666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shi Y.; Sánchez-Molina I.; Cao C.; Cook T. R.; Stang P. J. Synthesis and photophysical studies of self-assembled multicomponent supramolecular coordination prisms bearing porphyrin faces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 9390–9395. 10.1073/pnas.1408905111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K.; Akita M.; Prusty S.; Chand D. K.; Kikuchi T.; Sato H.; Yoshizawa M. Polyaromatic molecular peanuts. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15914. 10.1038/ncomms15914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt A.; Pakendorf T.; Reime B.; Meyer J.; Fischer P.; Stube N.; Panneerselvam S.; Lorbeer O.; Stachnik K.; Warmer M.; Rodig P.; Gories D.; Meents A. Status of the crystallography beamlines at PETRA III. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2016, 131, 1–9. 10.1140/epjp/i2016-16056-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogan Y.; Malpass-Evans R.; Carta M.; Lee M.; Jansen J. C.; Bernardo P.; Clarizia G.; Tocci E.; Friess K.; Lanč M.; McKeown N. B. A highly permeable polyimide with enhanced selectivity for membrane gas separations. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 4874–4877. 10.1039/C4TA00564C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Adams G. B.; O’Keeffe M.; Ruoff R. S. Van Der Waals surface areas and volumes of fullerenes. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 9465–9469. 10.1021/j100089a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Struch N.; Bannwarth C.; Ronson T. K.; Lorenz Y.; Mienert B.; Wagner N.; Engeser M.; Bill E.; Puttreddy R.; Rissanen K.; Beck J.; Grimme S.; Nitschke J. R.; Lutzen A. An octanuclearmetallosupramolecular cage designed to exhibit spin-crossover behavior. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 4930–4935. 10.1002/anie.201700832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Liu Y. M.; Xia D.; Li B. W.; Zhang Q. Y.; Sakurai T.; Tan Y. Z.; Seki S.; Xie S. Y.; Zheng L. S. Functional sulfur-doped buckybowls and their concave-convex supramolecular assembly with fullerenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 13047–13051. 10.1002/anie.201606383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Takeda M.; Hiroto S.; Yokoi H.; Lee S.; Kim D.; Shinokubo H. Azabuckybowl-based molecular tweezers as C60 and C70 receptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6336–6342. 10.1021/jacs.8b02327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Yokoi H.; Hiraoka Y.; Hiroto S.; Sakamaki D.; Seki S.; Shinokubo H. Nitrogen-embedded buckybowl and its assembly with C60. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8215. 10.1038/ncomms9215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wood D. M.; Meng W.; Ronson T. K.; Stefankiewicz A. R.; Sanders J. K.; Nitschke J. R. Guest-induced transformation of a porphyrin-edged FeII4L6 capsule into a CuIFeII2L4 fullerene receptor. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 3988–3992. 10.1002/anie.201411985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Schmittel M.; He B.; Mal P. Supramolecular multicomponent self-assembly of shape-adaptive nanoprisms: wrapping up C60 with three porphyrin units. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2513–2516. 10.1021/ol800796h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu R.; Bloch W. M.; Holstein J. J.; Mandal S.; Schäfer L. V.; Clever G. H. Donor-site-directed rational assembly of heteroleptic cis-[Pd2L2L’2] coordination cages from picolyl ligands. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 12976–12982. 10.1002/chem.201802188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang N.; Wang K.; Drake H.; Cai P.; Pang J.; Li J.; Che S.; Huang L.; Wang Q.; Zhou H. C. Tailor-made pyrazolide-based metal-organic frameworks for selective catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6383–6390. 10.1021/jacs.8b02710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kräutler B.; Müller T.; Duarte-Ruiz A. Efficient preparation of monoadducts of [60]fullerene and anthracenes by solution chemistry and their thermolytic decomposition in the solid state. Chem. - Eur. J. 2001, 7, 3223–3235. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Murata Y.; Kato N.; Fujiwara K.; Komatsu K. Solid-state [4 + 2] cycloaddition of fullerene C60 with condensed aromatics using a high-speed vibration milling technique. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 3483–3488. 10.1021/jo990013z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.