Abstract

Objectives

Education in regional anaesthesia covers several complex and diverse areas, from theoretical aspects to procedural skills, professional behaviours, simulation, curriculum design and assessment. The objectives of this study were to summarise these topics and to prioritise these topics in order of research importance.

Design

Electronic structured Delphi questionnaire over three rounds.

Setting

International.

Participants

38 experts in regional anaesthesia education and training, identified through the American Society of Regional Anesthesia Education Special Interest Group research collaboration.

Results

82 topics were identified and ranked in order of prioritisation. Topics were categorised into themes of simulation, curriculum, knowledge translation, assessment of skills, research methodology, equipment and motor skills. Thirteen topics were ranked as essential research priority, with four topics each on simulation and curriculum, three topics on knowledge translation, and one topic each on methodology and assessment.

Conclusions

Researchers and educators can use these identified topics to assist in planning and structuring their research and training in regional anaesthesia education.

Keywords: anaesthetics, regional anaesthesia, nerve blocks

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study lists the relevant topics in regional anaesthesia education and training and ranked them in order of research importance.

Topics were formatted using the British Medical Journal EPICOT (Evidence, Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Timestamp) guidelines and ranked using prospective Delphi questionnaires.

The results of this study are from selected experts in regional anaesthesia, and not surveyed from the entire anaesthesia research community.

Introduction

Regional anaesthesia (RA) has increased in popularity, particularly since the introduction of ultrasound-guided techniques. In expert hands, current RA techniques have the advantages of increased success, shorter onset time, reduced complications, reduced dose requirements and cost-effectiveness, over traditional techniques.1–3 Clinical expertise is in turn a reflection on the effectiveness of RA education and training. The skill sets required for successful and safe RA are complex and diverse, especially with the widespread uptake of ultrasound-guided regional anaesthesia (UGRA). They include anatomy, physiology, pharmacology, sonoanatomy, identification and optimisation of sonography images, and needle visualisation dexterity skills,4–8 as well as professional attributes of communication, teamwork, decision making and situational awareness.9 10

These technical skills have previously been published by the 2010 American Society of Regional Anesthesia (ASRA) and the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy joint committees.11 Furthermore, anaesthesia training programmes are being restructured from a time-based to competency-based models. An example in North America is the 2014 RA competency milestones published by the American Board of Anesthesiology/Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.12

Achieving these educational goals is a formidable challenge for our subspecialty. To assist in delivering this curriculum, the ASRA established an Education Special Interest Group (SIG) in April 2017. This study was initiated through the SIG research collaboration, composed of a multidisciplinary and multinational cooperation between clinicians, medical educators and psychologists.

This study has two objectives. The first objective is to help engagement of stakeholders (researchers, educationalists, clinicians and research grant reviewers) by providing a list of the current diversity of topics in RA education. Given the breadth of possible research activities, a second objective was to prioritise topics by order of research need. This prioritisation was performed by obtaining expert regional anaesthetists’ opinions on which topics are most relevant for RA education.

This study used a Delphi method, in which rounds of questionnaires are sent to participants. Advantages include anonymity, minimising bias from strong personalities, equal weighting of all opinions and not geographically restricted as electronic questionnaires are used. Similar prioritisation studies using this electronic Delphi method have been undertaken by other craft groups, including respiratory medicine, maternal/perinatal medicine and clinical anaesthesia.13–15 Our purpose in conducting this study is to prioritise scholarly attention and funding towards improving the evidence base for initiatives in RA education.

Methods

This prospective study used questionnaires to rank, in order of prioritisation, research topics relevant to RA education and training. Structured electronic Delphi questionnaires were sent via email to blinded participants. The study was performed between September 2017 and January 2018.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in this study.

Study participants

Potential participants were nominated by members of the research subcommittee of the ASRA Education SIG. The criterion for nomination was an established researcher or active contributor in RA education, evidenced by authorship of RA education journal articles and textbooks, directors of RA training programmes, or a member of national or international anaesthesia education committees and anaesthesia education working groups.

Nominees were invited via direct email to participate in this study. The study rationale and protocol were provided. This study is a negligible risk, anonymous survey of anaesthesia clinical academics. After reading the invitation and the protocol document, informed consent was given by each participant providing an affirmative reply to the invitation and study protocol.

Research topics in RA education

To create a list of articles that encompass research activities in RA education, we used the following source materials. First, a prior narrative review of RA education studies by Nix et al 8 contained a list of pertinent articles published up to August 2012. That review used the following literature search terms: ‘ultrasound-guided regional anaesthesia, UGRA, regional, local, ultrasound, guided, education, training, mentor, in-service, local anaesthesia, anesthesiology, medical education, continuing medical education, graduate medical education, and postgraduate education, January 1982 to August 2012’. We used the Medical Subject Headings search phrase regional anaesthesia (both UK and US spellings) as it encompasses all techniques, including daughter keywords local, spinal, epidural, nerve blockade, autonomic, brachial plexus and cervical plexus. Using the same strategy, the National Library of Medicine and Medline databases were searched to update the list of relevant articles from September 2012 to August 2017. The WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform was also searched using combinations of the following terms: ‘Regional Anesthesia, Regional Anaesthesia, Anesthesiology, Anaesthesiology, Education, Training, Simulation’. Lastly, a grey literature search was performed with the parameters ‘teaching ultrasound-guided regional anaesthesia to residents/trainee anaesthetists/anesthesiologists’.

Together, these articles and research studies provided a body of work of previous and current research avenues in RA education and training. Text in all works was also scrutinised for other suggestions and implications for future research. Individual research topics were then rewritten in EPICOT format (Evidence, Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Timestamp) using editorial guidelines from the British Medical Journal.16 This guideline seeks to present research recommendations in a format that emphasises specific research questions arising from available evidence. Both authors independently performed the tasks of reading through articles and rewriting the research topics in EPICOT format. After merging the list of topics, any differences in wording of the EPICOT statements were jointly discussed to reach consensus. This was performed collaboratively and primarily involved clarification or rephrasing of the statement to reduce ambiguity.

Round 1 screening

Three rounds of questionnaires were designed. In round 1, the initial list of EPICOT research topics was emailed to the participants. A 10-point Likert scale was used to rate each presented topic. Participants were asked to score each topic on its own merits, and not to rate topics against each other. The Likert scale used text anchors against the following numerical scores to assist rating: 1=not recommended for further research, 4=some value for research, 7=important area for research and 10=essential research. Participants could also provide suggestions for additional research topics in the free-text sections. Participants returned their round 1 scores directly to study investigator AC. Aggregate scores from all participants were used to calculate the median score for each topic.

A priori thresholds were predefined to categorise topics. A median score of ≥6, and for which ≥60% of the panel scored ≥6, was included for final prioritisation in round 3. This was a stringent threshold to select the highest ranked topics (scored at least high end of ‘important’ or ‘essential’), and also only considered to be this ranking by the absolute majority of participants. Topics which scored a median of ≤3 were excluded from further ranking.

Rounds 2 and 3 prioritisation

Topics with median scores between 3 and 6 in round 1 were reranked in round 2, along with the additional topics suggested by participants in round 1. To emphasise prioritisation of topics, instructions to participants were changed. Each topic was to be given a single score within a range of scores anchored with explicit text descriptions: 1–3 for ‘lowest research priority’, 4–7 for ‘interesting but intermediate in research priority’ and 8–10 for ‘essential research priority’. Participants were asked to select the appropriate priority category, to choose a score within that category and to rank topics in relative importance to each other. Topics which scored a median of ≤3 were excluded.

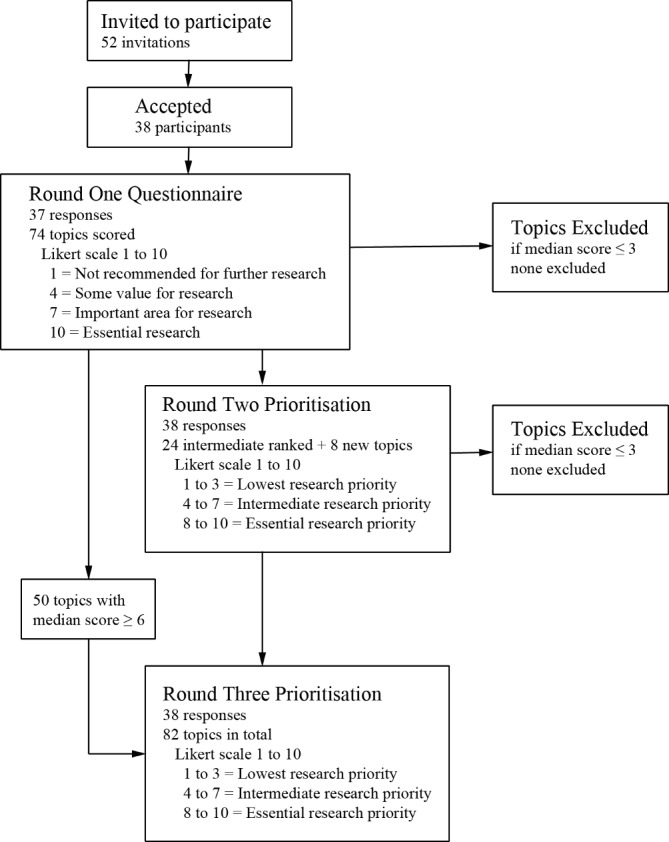

Round 3 was the final questionnaire and prioritised the topics identified as higher ranked in round 1, that is, a median score of ≥6 by more than 60% of the participants. This round used the same instructions and Likert scale as in round 2. Figure 1 illustrates this Delphi methodology.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study and summary of results at each Delphi round.

In all rounds, participants did not interact nor were they aware of the identities of other participants. A table summary of the previous round, with the median, IQR and absolute percentage of participants who scored ≥6 for all research topics, was provided to all participants. However, no individual scores or comments were identified in these summaries. Only study investigator AC had access to individual scores. Participants were given 3 weeks to score each round. Reminder emails were sent 1 week prior and 3 days after this deadline.

All scores were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (V.2016, Microsoft, Redmond, Washington). Descriptive statistics were performed and reported as median scores with 25th–75th IQR and as the proportion of all participants who scored 6 or higher for each topic.

Results

Fifty-two email invitations were sent. Thirty-eight participants (73%) accepted the invitation. Thirty-seven returned scores for round 1 (97% response). All 38 participants returned scores for rounds 2 and 3 (100% response). The 38 participants included 29 authors (76%) of RA education journal articles and RA textbook contributions, 20 training programme directors (53%), and 12 were also members of national or international anaesthesia education programmes (32%).

In round 1, participants ranked the 74 initially generated topics. Fifty topics reached the threshold of higher priority scores and were included in round 3. In round 2, 24 intermediate ranked topics were scored, along with 8 new topics suggested by participants. Based on predefined criteria, no topic was excluded in either round 1 or round 2. A total of 82 topics were thus ranked in order of research priority in round 3. These results are summarised in figure 1.

Topics were categorised into seven themes: research on structure and design of an RA training curriculum; the effectiveness of equipment and in vitro models in training RA skill sets; assessment of RA knowledge and skills; knowledge translation from practice and lectures to RA performance in a clinical setting; research methodology and protocol design of RA education studies; research on development, retention and proficiency of RA motor skills; and the role of simulation in RA education.

There were 13 topics ranked as ‘essential research priority’ by participants, defined as a median score of 8 or higher in round 3. These topics are listed in table 1. There were four topics each on simulation and curriculum, three topics on knowledge translation, and one topic each on methodology and assessment.

Table 1.

Topics scored as essential priority, listed in rank order

| Overall ranking | Topics | Theme | Median (IQR) | Proportion scored ≥6 (%) |

| 1 | What endpoints/milestones should be achieved on a simulator prior to clinical performance of UGRA? | Simulation | 8 (7–9) | 89 |

| 2 | Does simulation training show an improvement in clinical outcomes such as improved efficacy, time taken and less errors? | Simulation | 8 (6–9) | 89 |

| 3 | Which RA blocks should be considered as a core minimum set for all trainees? Are there benefits in teaching a subset of blocks to competency versus broader exposure to all blocks? | Curriculum | 8 (7–9) | 87 |

| 4 | Is UGRA knowledge and technical skill generalisable: when does proficiency in one block type transfer to other blocks? | Knowledge translation | 8 (7–8) | 87 |

| 5 | Does a rotation through a ‘block room’ provide better learning than programmes without a block room? | Curriculum | 8 (6.25–8) | 82 |

| 6 | Is there a minimum number of blocks to attain proficiency for each block or are the skills transferable? | Assessment | 8 (6.25–8) | 82 |

| 7 | Does simulation training bestow a safety advantage compared with proceeding directly to supervised practice in real patients? | Simulation | 8 (6–9) | 82 |

| 8 | What criteria should be used to evaluate the success of an UGRA residency training curriculum? | Curriculum | 8 (6–8) | 82 |

| 9 | What are the necessary components of a formal structured training programme? | Curriculum | 8 (6–8) | 82 |

| 10 | What should be consensus assessment tools to standardise RA education research? | Methodology | 8 (6–8) | 82 |

| 11 | What are the most efficacious means for practising anaesthesiologists (consultants) to learn blocks? | Knowledge translation | 8 (6–9) | 79 |

| 12 | Does deliberate practice in simulation improve RA proficiency? | Simulation | 8 (5–8.75) | 71 |

| 13 | How can trainees retain proficiency of knowledge and skills learnt after attending focused training (eg, RA rotation, simulation session, workshop)? | Knowledge translation | 8 (4.25–8) | 71 |

Only topics scoring 8 or higher included.

RA, regional anaesthesia; UGRA, ultrasound-guided regional anaesthesia.

Table 2 includes the next 24 topics scored as a 7, which is equivalent to the highest cohort of intermediate priority topics. Table 3 includes the 14 lowest ranked topics. The online supplementary tables recategorise all 82 topics into the seven themes of curriculum (online supplementary table S1), equipment (online supplementary table S2), assessment (online supplementary table S3), knowledge translation (online supplementary table S4), methodology (online supplementary table S5), motor skills (online supplementary table S6) and simulation (online supplementary table S7).

Table 2.

Intermediate ranked topics

| Overall ranking | Topics | Theme | Median (IQR) | Proportion scored ≥6 (%) |

| 14 | What should be consensus clinical endpoints to standardise RA education study endpoints? | Methodology | 7.5 (6–9) | 87 |

| 15 | How do you maintain or improve knowledge retention after a 1-day workshop? | Knowledge translation | 7.5 (6–8) | 79 |

| 16 | Do the type and quality of feedback provided by faculty/tutors have an impact on learning outcomes? | Simulation | 7 (6–8) | 87 |

| 17 | Do short-duration courses/workshops result in long-term changes in clinical practice? | Knowledge translation | 7 (6–8) | 82 |

| 18 | What is the best way to establish multicentre collaborative studies in RA education? | Methodology | 7 (6–8) | 79 |

| 19 | How can cusum methodology be used to track and provide quality assurance of RA clinical performance? | Methodology | 7 (6–8) | 79 |

| 20 | Does pretraining (ie, demonstrating competency of discrete tasks before further progression) result in improvement of RA knowledge and technical skills? | Knowledge translation | 7 (6–8) | 79 |

| 21 | What should be consensus simulation/laboratory endpoints to standardise RA education study endpoints? | Methodology | 7 (6–8) | 79 |

| 22 | What is the best way to teach sonoanatomy in ‘difficult’ patients (eg, in the morbidly obese, patients with previous surgery) | Curriculum | 7 (6–8) | 76 |

| 23 | What factors influence the common and recurring quality compromising behaviours observed in novices performing UGRA? What type of training is useful to remedy this behaviour? | Motor skills | 7 (6–8) | 76 |

| 24 | How regularly does a trainee need to perform a block to be able to perform it independently after residency? | Knowledge translation | 7 (6–8) | 76 |

| 25 | Is simulation training a cost-effective method of teaching, versus less resource-intensive alternatives? | Simulation | 7 (6–8) | 76 |

| 26 | How can we best use web-based/online resources (viewable content, social media, online assessments, video calls) to deliver teaching? | Methodology | 7 (6–8) | 76 |

| 27 | What is the optimum mix of lectures, workshops, courses, simulation and direct supervision required to teach RA? | Curriculum | 7 (5.25–8) | 74 |

| 28 | How do you improve preclinical visuospatial skill (assuming that visuospatial skill is correlated with UGRA motor skills)? | Motor skills | 7 (5.25–8) | 74 |

| 29 | What forms of instruction or strategies provide the most effective means of improving retention of sonoanatomy? | Curriculum | 7 (5.25–8) | 74 |

| 30 | Does greater technical ability (proficiency) lead to better outcomes? | Motor skills | 7 (5–8) | 71 |

| 31 | How do you improve poor coordination and fine motor control prior to clinical exposure? | Motor skills | 7 (5–8) | 71 |

| 32 | Does preprocedural knowledge or awareness of critical errors made by trainees lead to a reduction in clinical errors by trainees? | Knowledge translation | 7 (5–8) | 71 |

| 33 | Which tasks in UGRA require more resources, effort and practice to gain competency? | Methodology | 7 (5–8) | 71 |

| 34 | What are the factors promoting and inhibiting access to RA training? | Curriculum | 7 (5–8) | 66 |

| 35 | Is simulation training more effective in some areas of RA education (eg, knowledge retention vs technical skills) than in other areas? | Simulation | 7 (5–8) | 63 |

| 36 | In resource-poor countries, what is the best combination of textbooks, accessible online modules and videos, telemedicine, and live model scanning to deliver an RA curriculum? | Curriculum | 7 (4–8) | 63 |

| 37 | What are the contributing factors to the practice and impediment of trainees performing RA after residency training? | Knowledge translation | 7 (4–8) | 58 |

Only topics scoring 7 included.

RA, regional anaesthesia; UGRA, ultrasound-guided regional anaesthesia.

Table 3.

Lowest ranked topics

| Overall ranking | Topics | Theme | Median (IQR) | Proportion scored ≥6 (%) |

| 69 | Which blocks, or when, is neurostimulation best used to assist location of the needle tip? | Equipment | 5 (2.25–6) | 47 |

| 70 | Does simulation training show an improvement in non-technical attributes such as communication, teamwork, professionalism and resource management? | Simulation | 5 (3–7) | 47 |

| 71 | What is the best way to teach neuraxial sonoanatomy? | Curriculum | 5 (3.25–7) | 47 |

| 72 | What is the best way to teach ergonomic principles and practices necessary for performing RA blocks? | Curriculum | 5 (3–7) | 47 |

| 73 | In what situations is the learning outcomes from self-directed teaching no different from deliberate feedback? | Assessment | 5 (4–7) | 45 |

| 74 | Do electromagnetic guidance modalities (radiofrequency tracking, needle magnetic currents) assist in needle tip and shaft localisation in UGRA? | Equipment | 5 (3–6.75) | 42 |

| 75 | Which of the high-fidelity cadaver models (ie, Thiel, fresh frozen, Batson, formalin) offer the best compromise between face validity, construct validity, availability and cost? | Equipment | 5 (4–7) | 42 |

| 76 | Which of the low-fidelity phantoms (ie, gelatine, agar, tofu) offer the best compromise between face validity, construct validity, availability and cost? | Equipment | 5 (4–7) | 42 |

| 77 | Is there a role for a progression from low-fidelity to high-fidelity UGRA phantoms in teaching RA? | Equipment | 5 (3–7) | 42 |

| 78 | Does 3D/4D ultrasound assist needle tip guidance in UGRA? | Equipment | 5 (2.25–6.75) | 34 |

| 79 | Should we screen for technical and non-technical qualities predisposing to procedural skills proficiency when selecting residents during the employment process? | Assessment | 4 (2–7.75) | 39 |

| 80 | Which of the meat-based models (eg, pork, beef, turkey) offer the best compromise between face validity, construct validity, availability and cost? | Equipment | 4 (3–6) | 32 |

| 81 | Do rigid needle trajectory guides (clip on accessory to transducers) assist in needle tip and shaft localisation in UGRA? | Equipment | 4 (3–6) | 29 |

| 82 | Does robotic assistance aid needle tip positioning for RA? | Equipment | 3 (2–5.75) | 26 |

Topics scoring 5 or less included.

3D, three-dimensional; 4D, four-dimensional; RA, regional anaesthesia; UGRA, ultrasound-guided regional anaesthesia.

bmjopen-2019-030376supp001.pdf (99.4KB, pdf)

For all tables, topics are arranged in order of highest to lowest overall median score, and then by order of proportion of participants who scored at least 6 in round 3.

Discussion

This study summarised the large and diverse body of research activities in RA education. These research activities were rewritten as 82 research topics and scored by a panel of expert participants, who ranked these topics in order of importance. Thirteen topics were found to be of essential priority, and resolving these specific questions would advance our current understanding of RA education.

Four of these topics were on the role of simulation. Further evidence is required to inform appropriate learning objectives and competency milestones during simulation training. In turn, deliberate practice is the educational technique that describes repetitive practice using these predefined learning outcomes, with structured feedback by expert faculty.17 While evidence for deliberate practice exists in RA ultrasound-guided needle guidance studies,18 19 the effectiveness of deliberate practice in RA simulation training was identified as a priority research area. Determining whether simulation training ultimately influences patient outcomes, such as improved safety, faster performance and higher efficacy, versus traditional clinical exposure, was also regarded as priority. Indeed, a recent systematic review of randomised controlled trials found only one study looked at patient outcomes after simulation training in RA.6

There were four curriculum topics ranked as essential. A description of a redesigned RA curriculum,20 based on a framework for systematic training and assessment of technical skills,21 has been previously published. Our study found, however, that further work is required to help define the characteristics of an ideal RA curriculum, including what are the core RA skill sets. Evaluation of success of the curriculum was also deemed to be a priority. Many institutions have dedicated RA ‘block rooms’, but measuring effectiveness of this initiative remains elusive. A recent article, published after this study commenced, found that surrogate measures of analgesia, pain scores and opioid consumption were reduced after introduction of a block room.22

Questions remained about the ability of physicians to maintain RA knowledge and motor skills. This was identified as translation of skill sets between different RA procedures, and whether anaesthetists (trainees or consultants) can retain new information learnt at workshops and simulation into clinical practice.

The two remaining essential priority topics were on assessment of the RA procedural skill. This involved defining the minimum competency for each RA task, and to reach consensus on which assessment tools should be used to evaluate competency. A systematic review has recently summarised the available assessment tools for RA procedures.23

The strengths of this prioritisation exercise include using a prospective, structured, electronic Delphi technique. Expert regional anaesthetists participated in categorising research topics over three iterative rounds of scoring, with an excellent response rate. The panel was international, with a large proportion contributing to the subspecialty as original journal authors and directors of RA training. The de-identified nature of scoring reduces bias from strong personalities influencing the consensus outcomes. Lastly, we predefined a priori thresholds for defining consensus, an important feature of robust Delphi studies.24

We thus believe that the essential priority topics identified in this study are clinically relevant to anaesthetists involved in RA education. For researchers, our results provide guidance on research activities that deliver the highest clinical and educational impact. Conversely, we do not imply that research in lower ranked topics is discouraged. As examples, topics in the top 30 are still rated highly by >70% of participants and include questions on standardising outcome measures in RA studies, as well as characterising and remediating quality compromising behaviours by novices.

There are several limitations to our study. Participants in this study are active and passionate RA educators and anaesthetists. Nonetheless, the sample size of 38 experts will not be representative of the entire RA research community, nor did we include anaesthesia trainees or public representatives who may harbour different weightings for the research priorities due to their unique perspectives. Even within this small panel, there were divergent opinions on the ranking of each topic, evidenced by relatively wide IQRs. Surveying RA programme directors in all RA societies worldwide may not necessarily provide a narrower result: the relative value each participant places on a specific topic will be influenced by their personal experiences and learning environments, and is a possible explanation of the differences in scoring. This subjective bias is minimised, but not fully removed, by imposing a minimum of two rounds of scoring for each topic and by aggregating scores from all participants.

Each study in the round 1 topic generation phase was treated independently when creating the EPICOT statements. This resulted in research topics with similar wording, and potentially could have been condensed. However, a strength of EPICOT is that the generated statements preserve context.16 For example, the question ‘standardizing outcome measures in RA education’ was ranked differently if related to assessment tools (rank 10), versus patient clinical outcomes (rank 14) and in a simulation context (rank 21). This allows researchers to help refine specific research activity.

The online supplementary tables reformat all 82 topics based on themes of curriculum, equipment, assessment, knowledge translation, methodology, motor skills and simulation. We caution that these themes are subjective and were categorised post hoc, as presented in the online supplementary tables. During the prioritisation phase, participants ranked topics without these thematic labels, and the tables were created only during manuscript preparation. Several topics could be classified under multiple themes. Our results have been presented using thematic organisation, as this may help researchers appreciate important directions and similarities within each theme. A group concept mapping exercise would be a more structured approach to elicit expert opinion on how different but related research topics could be classified.

In conclusion, we present the results of a Delphi study designed to summarise and then rank RA education topics in order of research priority. Experts in RA education, identified through a collaborative process within the ASRA Education SIG, were invited to participate. The 13 essential topics are diverse in nature, encompassing the role of simulation training, curriculum design, assessment of skills and retention of skills, in RA. The complete list of 82 topics should be considered by researchers when deciding how best to concentrate their efforts in the advancement of education in our subspecialty.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the ASRA Education in Research Collaboration and the following regional anaesthesia experts who were involved in this study (in alphabetical order): K Ahn, M Barrington, KJ Chin, M Chiu, I Costache, L de Gray, C Delbridge, J Dolan, R Endersby, B Fox, A Hadzic, G Iohom, R Ivie, R Johnson, K Kwofie, J Macachor, N Maclennan, R Maniker, E Mariano, C McCartney, G McLeod, J McVicar, P Merjavy, L Moran, V Naik, A Niazi, C Mitchell, H Mulchandani, S Orebaugh, D Persaud, S Grant, K Srinivasan, J Stimpson, L Turbitt, A Udani, P Wong, D Wong and G Woodworth.

Footnotes

Contributors: AC and RR jointly conceived the study, wrote and approved the final manuscript. AC performed data collection and statistical analysis.

Funding: Internal funding from departmental funds only.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data is available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Neal JM, Brull R, Horn JL, et al. The second american society of regional anesthesia and pain medicine evidence-based medicine assessment of ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia: Executive summary. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2016;41:181–94. 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu SS. Evidence basis for ultrasound-guided block characteristics onset, quality, and duration. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2016;41:205–20. 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lewis SR, Price A, Walker KJ, et al. Ultrasound guidance for upper and lower limb blocks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD006459 10.1002/14651858.CD006459.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scholten HJ, Pourtaherian A, Mihajlovic N, et al. Improving needle tip identification during ultrasound-guided procedures in anaesthetic practice. Anaesthesia 2017;72:889–904. 10.1111/anae.13921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kessler J, Wegener JT, Hollmann MW, et al. Teaching concepts in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2016;29:608–13. 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen XX, Trivedi V, AlSaflan AA, et al. Ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia simulation training: A systematic review. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2017;42:741–50. 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Niazi AU, Peng PW, Ho M, et al. The future of regional anesthesia education: lessons learned from the surgical specialty. Can J Anaesth 2016;63:966–72. 10.1007/s12630-016-0653-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nix CM, Margarido CB, Awad IT, et al. A scoping review of the evidence for teaching ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2013;38:471–80. 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3182a4ed7a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fletcher GC, McGeorge P, Flin RH, et al. The role of non-technical skills in anaesthesia: a review of current literature. Br J Anaesth 2002;88:418–29. 10.1093/bja/88.3.418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith AF, Pope C, Goodwin D, et al. What defines expertise in regional anaesthesia? An observational analysis of practice. Br J Anaesth 2006;97:401–7. 10.1093/bja/ael175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sites BD, Chan VW, Neal JM, et al. The american society of regional anesthesia and pain medicine and the european society of regional anaesthesia and pain therapy joint committee recommendations for education and training in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2010;35:S74–S80. 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181d34ff5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. The Anesthesiology Milestone project. J Grad Med Ed 2014;6:15–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Souza JP, Widmer M, Gülmezoglu AM, et al. Maternal and perinatal health research priorities beyond 2015: an international survey and prioritization exercise. Reprod Health 2014;11:61 10.1186/1742-4755-11-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sheikh A, Major P, Holgate ST. Developing consensus on national respiratory research priorities: key findings from the uk respiratory research collaborative’s e-delphi exercise. Respir Med 2008;102:1089–92. 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boney O, Bell M, Bell N, et al. Identifying research priorities in anaesthesia and perioperative care: final report of the joint national institute of academic anaesthesia/james lind alliance research priority setting partnership. BMJ Open 2015;5:e010006 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown P, Brunnhuber K, Chalkidou K, et al. How to formulate research recommendations. BMJ 2006;333:804–6. 10.1136/bmj.38987.492014.94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Slater RJ, Castanelli DJ, Barrington MJ. Learning and teaching motor skills in regional anesthesia: a different perspective. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2014;39:230–9. 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barrington MJ, Wong DM, Slater B, et al. Ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia: how much practice do novices require before achieving competency in ultrasound needle visualization using a cadaver model. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2012;37:334–9. 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3182475fba [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chuan A, Lim YC, Aneja H, et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing meat-based with human cadaveric models for teaching ultrasound-guided regional anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2016;71:921–9. 10.1111/anae.13446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith HM, Kopp SL, Jacob AK, et al. Designing and implementing a comprehensive learner-centered regional anesthesia curriculum. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009;34:88–94. 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31819e734f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aggarwal R, Grantcharov TP, Darzi A. Framework for systematic training and assessment of technical skills. J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:697–705. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chin A, Heywood L, Iu P, et al. The effectiveness of regional anaesthesia before and after the introduction of a dedicated regional anaesthesia service incorporating a block room. Anaesth Intensive Care 2017;45:714–9. 10.1177/0310057X1704500611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chuan A, Wan AS, Royse CF, et al. Competency-based assessment tools for regional anaesthesia: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth 2018;120:264–73. 10.1016/j.bja.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:401–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030376supp001.pdf (99.4KB, pdf)