Abstract

Background

Better understanding, documentation and evaluation of different refugee health interventions and their means of health system integration and intersectoral collaboration are needed.

Objectives

Explore the barriers and facilitators to the integration of health services for refugees; the processes involved and the different stakeholders engaged in levaraging intersectoral approaches to protect refugees’ right to health on resettlement.

Design

Scoping review.

Methods

A search of articles from 2000 onward was done in MEDLINE, Web of Science, Global Health and PsycINFO, Embase. Two frameworks were applied in our analysis, the ‘framework for analysing integration of targeted health interventions in systems’ and ‘Health in All Policies’ framework for country action. A comprehensive description of the methods is included in our published protocol.

Results

6117 papers were identified, only 18 studies met the inclusion criteria. Facilitators in implementation included: training for providers, colocation of services, transportation services to enhance access, clear role definitions and appropriate budget allocation and financing. Barriers included: lack of a participatory approach, insufficient resources for providers, absence of financing, unclear roles and insufficient coordination of interprofessional teams; low availability and use of data, and turf wars across governance stakeholders. Successful strategies to address refugee health included: networks of service delivery combining existing public and private services; system navigators; host community engagement to reduce stigma; translation services; legislative support and alternative models of care for women and children.

Conclusion

Limited evidence was found overall. Further research on intersectoral approaches is needed. Key policy insights gained from barriers and facilitators reported in available studies include: improving coordination between existing programmes; supporting colocation of services; establishing formal system navigator roles that connect relevant programmes; establishing formal translation services to improve access and establishing training and resources for providers.

Keywords: intersectoral, right to health, access, refugees, integration, resettlement

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study employs a systematic approach by using two frameworks, the ‘framework for analysing integration of targeted health interventions in systems’ and ‘Health in All Policies’ framework for country action to develop a stronger understanding of the processes and actors involved in integration and intersectoral action.

Our findings can be applied for policy and action aiming to enhance the integration of refugee health services within health systems, and identifying research needs to advance the right to health for refugees.

The lack of evidence on intersectoral and integrated approaches from low-income and middle-income countries may impact the generalisability of the findings.

Introduction

Upholding the right to health is a fundamental challenge for governments worldwide, particularly when providing services to vulnerable or hard to reach populations such as refugees. The Office of the United Nations High Commission for Human Rights identifies the right to health as a fundamental part of human rights, first articulated in the 1946 Constitution of WHO.1 Entitlements under the right to health include universal health coverage—now a target under Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3—broadly covering access to preventative and curative services, essential medicines, timely basic health services, health-related education, participation in health-related decision making at both national and community levels, as well as financial protection.1 2 Especially relevant to the plight of refugees, the right to health includes non-discrimination whereby health services, commodities and facilities must be provided to all without any discrimination. Lastly, these health services must be accessible, medically and culturally appropriate, available in adequate amount and quality, which includes having a trained health workforce, safe products and sanitation.2

‘Refugees’ are individuals fleeing armed conflict or persecution as defined by the 1951 Refugee Convention which also identifies their basic rights, specifically that refugees should not be returned to situations that are deemed a threat to their life or freedom.3 A key distinction of refugee rights is that they are a matter of national legislation, and of international law.4 Despite these legal protections, refugees face many challenges in accessing health services, especially more vulnerable groups like women and children.5 Many states explicitly exclude refugees from the level of protection afforded to their citizens, instead choosing to offer ‘essential care’ or ‘emergency healthcare’, which is differentially defined across countries.6 The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, and the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, both include general statements that hold States accountable to ‘the right of non-citizens to an adequate standard of physical and mental health by, inter alia, refraining from denying or limiting their access to preventive, curative and palliative health services’.7 The increasing number of refugees over the past years makes the realisation and protection of these rights both a legal, ethical and a logistical challenge.5 In addition, the boundaries of the right to health have expanded due to increased understanding of social determinants of health and the health impacts of the lived environment.8 9 Refugees face challenges in navigating health, legal, education, housing, social protection and employment services, which further threatens their quality of life and health status.10 Therefore, a lack of coordination and integration across these services undermines their effectiveness.11

Much like the shift from the more vertical approaches of the millennium development goals towards the more integrated SDGs, the protection of the right to health calls for an intersectoral approach whereby health is applied to all policies for all people.12 As such, for states to effectively protect the right to health for refugees, there is a need to work across sectors and disciplines to better integrate targeted programmes and initiatives, thereby improving standards of care during resettlement. Some evidence exists that supporting collaboration and coordination across social services for refugees improves the effectiveness and quality of care received.10 Many fragmented psychosocial programmes exist across sectors to attempt to address the unique challenges faced by refugees but these are largely unevaluated and lack sustainability.13 14 Better understanding, documentation, evaluation and reporting of the dynamic nature of different interventions, and their means of health system integration and intersectoral collaboration, are necessary to ensure that lessons learnt are implemented in the design of future policies and programmes.

Therefore, we conducted a scoping review that describes the barriers and facilitators to integrated health services for refugees; the process involved in protecting refugee health; and the different stakeholders engaged in leveraging intersectoral approaches to protect refugees’ right to health on resettlement. We focused on three specific research questions:

What are the barriers and facilitators in integrating targeted services for refugees within existing health systems?

What strategies are involved in addressing refugees’ right to health on resettlement?

Which stakeholders are involved in leveraging intersectoral approaches to protect refugees’ right to health?

Methods

Study design

We selected the scoping review method as we were interested in mapping the concepts relevant to the complex nature of this topic, the changing global landscape around it, and the emerging and diverse knowledge base, which makes the method well matched to our research objectives.15 16 We drafted a scoping review protocol following the methods outlined by the Joanna Briggs Institute Methods Manual for scoping reviews.17 Our protocol was registered with the Open Science Framework,18 and published in BMJ Open.19 Since our full methods are available in the published protocol, a summary is provided below.19

Information sources and search strategy

A search of articles was done by two experienced librarians at the Karolinska Institutet using the following electronic databases: MEDLINE, Web of Science, Global Health and PsycINFO, Embase. See online supplementary appendix I for the comprehensive search strategy. Search terms included umbrella terms for three topics: refugees (eg, immigrants, migrants, asylum seekers, transients); health and social services (eg, healthcare, patient experience, health services, interdisciplinary, intersectoral collaboration, access to care)and health equity (eg, disparities, social determinants, rights-based approaches). These were combined to comprise the search (detailed search terms in online supplementary appendix).

bmjopen-2019-029407supp001.pdf (74.9KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

Population

Refugees as defined by the 1951 Refugee Convention.3

Intervention

A programme, approach or technical innovation that aims to protect refugees’ right to health, including interventions aimed at addressing the social determinants of health. Interventions outside of the health sector that affect health were included.

Comparators

This component was not necessary as the focus was on gauging the state of evidence.

Outcomes

Eligible studies and papers include those discussing plans for action, strategies, barriers, facilitators or outcomes using an intersectoral approach.

Types of studies included

Randomised control trials, pre–post design evaluations, qualitative evaluations and economic evaluations were included. Further, implementation research and operations research studies were eligible for inclusion, as well as studies or reports outlining stakeholder experiences and plans.

Exclusion criteria

Papers published in a language other than English were excluded. Other categories of migrants were not included as their legal entitlements are different to those of refugees which are protected under international law. If the studies did not display some level of integration nor intersectorality, they were not assessed further.20 Studies or commentaries that solely discuss theories and conceptual models were excluded.

Time period

Only studies from 2000 onward have been included.

Setting

Eligible studies are set in countries receiving refugees and asylum seekers (who may eventually qualify for refugee status) and serving as hosts for resettlement.

Frameworks to address research questions

Two published frameworks were used in our analysis to understand integration of health services within health systems and to analyse intersectoral approaches to support these services. The first framework by Atun et al,21 is a tool for analysing integration of targeted health interventions in health systems, where integration is defined as ‘the extent, pattern and rate of adoption and eventual assimilation of health interventions into each of the critical functions of a health system’.21 The framework for integration was also used to assess the process, and actors involved in integration.20

The second framework applied in our analysis is that of the Health in All Policies (HiAP) framework for country action. HiAP is defined as a way for countries to protect population health through ‘an approach to public policies across sectors that systematically takes into account the health implications of decisions, seeks synergies and avoids harmful health impacts in order to improve population health and health equity’.22 Components of this framework, adapted to refugee needs, were used in the review to frame barriers and facilitators in integrating refugee services through intersectoral collaboration.

Data abstraction

A data abstraction chart was developed based on the two frameworks used in this study. The chart was tested by two researchers and revised as appropriate. The revised chart was used by the same researchers to abstract descriptive and qualitative data as relevant to the elements of the frameworks used. Elements included in the chart were: intervention description; barriers and facilitators; contextual details; target population; type of evaluation; outcomes; stakeholder involvement in governance, financing, planning, service delivery, monitoring and evaluation, and engagement. Deductive reasoning was used to identify barriers and facilitators in intersectoral collaboration for refugee health. Open coding was applied to visualise themes across interventions as well as barriers and facilitators.23 Axial coding was applied to then draw connections to enabling strategies for intersectoral collaboration.23 General conclusions were drawn based on these themes, leading to suggestions for strengthening programmes and policies.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement required in conducting this scoping review.

Results

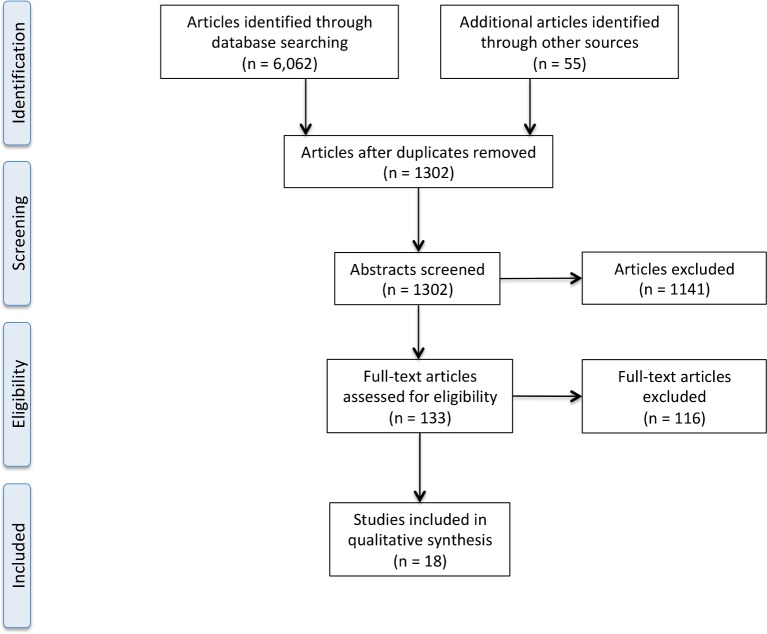

Of the 6117 records identified through the search strategy, 1302 abstracts were screened after removing duplicates. A total of 1141 were excluded based on exclusion criteria described above as assessed by two independent reviewers, 131 full texts were assessed, with the references of 15 selected articles additionally screened for inclusion criteria, a total of 18 studies were included in our review (see figure 1). Five studies were programmes or interventions carried out in the USA, one in Australia, two in Canada, one in Ethiopia and Uganda, and one in each of the following: Italy, Lebanon, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain and the UK (See table 1). Six studies were interventions at the district/local level, four at a broader regional level and five at the national level. The interventions outlined in the included studies addressed mostly all genders and all age ranges with the exception of six that targeted vulnerable groups: two studies on mothers and children24 25; one on the elderly26; one on students27 and two on women and girls.28 29 Interventions targeting women and children in particular used alternative models of care such as mobile health clinics28 29 and school-based interventions.24 27 Seven studies applied qualitative approaches (primarily in-depth interviews) for evaluation,27–33 four studies used survey tools or standardised assessment tools25 26 34 35; four studies used descriptive and routine data24 36–38; and three studies were mainly descriptive analysis reporting on and looking at the outcomes of case examples and policies.39–41

Figure 1.

Scoping review flow chart.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies

| Author | Year | Title | Intervention | Barriers | Facilitators | Country |

| Calvo et al 30 | 2014 | The Effect of Universal Service Delivery on the Integration of Moroccan Immigrants in Spain: A Case Study from an Anti-Oppressive Perspective | Addressing stigma and host community perceptions; system navigator (intercultural mediator). | Minimal involvement of target community in design of programme; considerations of forced assimilation through integration. | Decreased prejudice due to increased contact between host and immigrant communities; clear communication to host community around allocation of resources thereby reducing perceived threat of competition. | Spain |

| Catarci34 | 2012 | Conceptions and Strategies for User Integration across Refugee Services in Italy | Integrated reception of refugees and asylum seekers (network of hospitals and health services, public employment services, vocational training and continuing education agencies, etc). | Service coordinators lack tools to support integrated services; lack of continuity between theory and practice in continuing education support. | Service coordinators with access to continuing education were more likely to report adequate support; continuing education with intimate knowledge of the context, user needs and legislation related to refugee inclusion; coordinators should also have a solid network and an ability to distinguish between resources. | Italy |

| Cowell et al 25 | 2009 | Clinical Trail Outcomes of the Mexican American Problem Solving Program (MAPS) | A cognitively based problem solving programme delivered on linked home visits to mothers and after school programme classes to children. | Difficulty managing case load by school nurse of home visits and classes. | Communication and engagement with the community; partnership with the school. | USA |

| Geltman and Cochran38 | 2005 | A Private-Sector Preferred Provider Network Model for Public Health Screening of Newly Resettled Refugees | Public–private partnerships using a preferred provider network model for conducting refugee health screening. | Lack of appropriate funding model leading to delays in health screening. | Funding streams approved allowed procurement of services; network of providers created; dedicated training of physicians within the network. | USA |

| Guruge et al 29 | 2010 | Immigrant women’s experiences of receiving care in a mobile health clinic | Mobile health clinic for reproductive health services for immigrant women. | Lack of awareness of available services and navigating health systems; language barrier; fear of deportation leading to lack of use of services. | Colocation of services due to the mobile nature of the clinic. | Canada |

| Kim et al 36 | 2002 | Primary health care for Korean immigrants: sustaining a culturally sensitive model | Translation support; integrated health and social care; mental health support; bilingual advanced nurse practitioner and community advocate serve as system navigators. | Budgetary restrictions; existing restrictions in the roles that nurses can play in outreach. | Effective communication around availability of new programme; effective communication to announce new outreach and navigation role; efforts to build consensus and coherence across interprofessional teams; clear articulation of the role of advance nurse practitioners and their complementary role. | USA |

| Lilleston et al 28 | 2018 | Evaluation of a mobile approach to gender-based violence (GBV) service delivery among Syrian refugees in Lebanon | GBV mobile support service, providing safe spaces, community outreach, psychosocial support activities, safe legal and medical referrals, survivor- approach, adherence to confidentiality and access to face-to-face and phone-based case management. | Trust building is a key element and so constant mobility of target audience presented a challenge as did referral of services as quality medical and legal services were not always safe or available. | Integration of legal and medical teams in mobile GBV support teams; community mobilisers/system navigator role is a key function. | Lebanon |

| Macfarlane et al 33 | 2009 | Language barriers in health and social care consultations in the community: A comparative study of responses in Ireland and England | Translation support | Use of unpaid interpreters from patients’ social networks is complex; only one accredited course for professional interpreters; use of professional interpreters patchy due to low quality and institutional challenges in their acquisition. | In England where there is a policy to use language services (race equality policy), there is more use than in Ireland but implementation remains poor. | UK |

| McMurray et al 35 | 2014 | Integrated Primary Care Improves Access to Healthcare for Newly Arrived Refugees in Canada | Translation support; integrated health and social care; Gateway services and system navigators. | Shortage of primary care physicians which is the gateway; bureaucracy when billing Canada’s Interim Federal Health Program that provides coverage for healthcare costs until provincial health insurance is available. | Relationships between local physician community and case workers (navigators); timely transfer of records; ongoing consultations post-transfer. | Canada |

| McNaughton et al 24 | 2010 | Directions for Refining a School Nursing Intervention for Mexican Immigrant Families | Active case finding and problem solving through education system (school nurses); translation support | Schools with no existing nursing outreach programme were difficult to start at. | Nursing role was recognised and accepted by immigrant communities; schools that had a nursing programme already could expand it to active case finding with immigrant families. | Mexico |

| Mortensen31 | 2011 | Public Health System Responsiveness To Refugee Groups In New Zealand: Activation From The Bottom Up | Physician-driven needs-based programmes in primary care. | Mismatch between policies at national versus local level; lack of demographic data; no long-term planning or projected needs; low linkages between district health branch, public health offices and non-governmental organisations (NGOs); low health literacy due to lack of translated materials. | Quota refugees have same access to services as host communities; local action activated by physicians and community leaders led to more coverage and higher quality services in specific areas that had more advocacy. | New Zealand |

| Philbin et al 40 | 2018 | State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the USA | Policies to address social and legal determinants of health as they relate to immigrant populations. | Exclusionary policies affect social determinants of health, especially in mixed status families; families unwilling to participate in social programmes due to fear and confusion over entitlements; structural racism; restrictions in accessing education and employment; low mobility and relocation to remote areas with low availability of integrated social services. | Elimination of waiting period in several states for access to Medicaid regardless of immigration status; extra funding to federally qualified health centres. | USA |

| Stewart et al 32 | 2008 | Multicultural Meanings of Social Support among Immigrants and Refugees | Policies to address social and legal determinants of health as they relate to immigrant populations; social networking. | Inadequate financial and human resources, limited agency mandates, ineffective collaboration with other sectors, and low staff morale; collaboration impeded by the volume of organisations involved. | Existing networks of longer term immigrants were supportive in overcoming access barriers. | Canada |

| Tuepker and Chi41 | 2009 | Evaluating integrated healthcare for refugees and hosts in an African context | Integrating host and refugee healthcare by reorganising ministries to incorporate refugee services into existing portfolios rather than under one ministry. | Lack of evidence on the added value of integrated care; concern around minimising exceptional status of refugees; no legal obligation to provide integrated care; turf wars across organisations and sectors. | Funding streams from international organisations to national health services. | Ethiopia and Uganda |

| Verhagen et al 26 | 2013 | Culturally sensitive care for elderly immigrants through ethnic community health workers (CHWs): design and development of a community based intervention programme in the Netherlands | Use of ethnically similar CHWs to deliver health and social care; active case finding; community-driven problem solving with oversight by CHWs. | Lack of participation by target community in culturally sensitive design; limited knowledge by target community around availability of services. | Use of ethnically similar CHWs. | Netherlands |

| Woodland et al 27 | 2016 | Evaluation of a school screening programme for young people from refugee backgrounds | Active case finding and problem solving through education system (school nurses); translation support. | Poor integration of multiple service providers; lack of funding. | Integration within the school; informal communication between clinicians and the school. | Australia |

| Woodland et al 39 | 2010 | Health service delivery for newly arrived refugee children: A framework for good practice | Comprehensive, screening services; partnerships between community and health services (refugee health nurse as system navigator); transportation services to access centres; specific training provided to physicians and other care providers, including referral pathways; Pharmaceutical benefit scheme addressing refugee needs. | Lack of coordinated policy for all categories of refugees and asylum seekers; administrative burden of primary health care (PHC) coordination; lack of information for managing conditions specific or prominent to refugees. | Family-based services (colocation to address family needs); refugee health nurses (system navigators) decrease administrative burden of coordination; consumer participation and consultation; colocation of screening services; transportation support for getting to services; strong health information systems; data and consultations used to inform the direction of intersectoral collaboration and nature of partnerships between health and community service providers. | Australia |

| Yeung et al 37 | 2004 | Integrating psychiatry and primary care improves acceptability to mental health services among Chinese Americans | Specific training provided to physicians and other care providers; mental health support (colocation of mental health services); primary care nurse as a bridge/system navigator for referrals. | Funding for coordination outside purview of essential services; lack of knowledge on culturally appropriate mental health services. | Colocation of primary care and mental health services; designated staff as the bridge; training of service providers. | USA |

To respond to research question 1, each of the interventions and summarised barriers and facilitators are described in table 1 and grouped by common themes in table 2. Common facilitators identified in programmes and approaches to protect refugee health through intersectoral approaches and integration of services include: strong communication of programme availability, tools and training for providers, colocation of services, transportation services to enhance access, clear role definitions, interprofessional team and relationship management across providers, appropriate allocation of budget and financing and coordinated refugee-specific policies.

Table 2.

Barriers and facilitators commonly discussed across studies

| Elements | Element present as barrier | Element present as facilitator |

| Community engagement | Calvo et al 30: Verhagen et al 26 | Kim et al 36; Mortensen31; McMurray et al 35; Cowell et al 25 |

| Communication between host and refugee communities | Calvo et al 30; Woodland et al 27 | |

| Tools/training for service providers to support integrated services | Catarci34; MacFarlane et al 33; Woodland et al 39 | Woodland et al 39; Yeung et al 37; Geltman and Cochran38 |

| Colocation of services | Woodland et al 39; Yeung et al 37; Lilleston et al 28; Guruge et al 29 | |

| Transportation | Woodland et al 39 | |

| Networks between providers | Catarci34; Stewart et al 32; Geltman and Cochran38 | |

| Budget/appropriate funding streams | Kim et al 36; McMurray et al 35; Stewart et al 32 | Philbin et al 40; Tuepker and Chi41; Geltman and Cochran38 |

| Role definitions | Kim et al 36 | McNaughton et al 24; Lilleston et al 28; Yeung et al 37 |

| Interprofessional team management | Stewart et al 32; Woodland et al,27 | Kim et al 36 |

| Refugee-specific policies | Mortensen31; Philbin et al 40; Tuepker and Chi41; Woodland et al 39; Lilleston et al 28 | MacFarlane et al 33; Philbin40 |

| Data | Mortensen31; Tuepker and Chi41 | |

| Organisational turf | Stewart et al 32; Tuepker and Chi41 |

Barriers articulated include: lack of a participatory approach, poor communication leading to stigma and underuse of services, insufficient resources given to providers, absence of financing, unclear roles and insufficient coordination of interprofessional teams, exclusionary refugee policies, low availability and use of data and turf wars across governance stakeholders. Table 2 highlights the studies that expand on these themes as barriers or facilitators.

To respond to research question 2, this section will summarise common themes identified as enabling strategies that support intersectoral collaboration to promote refugee health. Strategies identified in this review include: establishing networks of service delivery through a combination of existing public and private services, establishing a system navigator role, engaging host communities to reduce stigma, ensuring availability of translation services, outreach, and advocacy and legislative support. Table 3 highlights the studies that address each of these strategies. In Italy, for example, networks were promoted among private and public authorities and service providers, including health, employment, vocational training and continuing education services.34 In this model, users moved through the pathways of integration and can receive support for any combination of health needs, access to education, housing support and legal assistance.34 Collaborative design and delivery of services was also demonstrated in Australia with support from multidisciplinary, intersectoral teams, but a lack of funding presented barriers to the potential success of this initiative.27 Similarly in the USA, the ‘Bridge Project’ faced insufficient funding in the coordination of care despite seeing promising results from use of a system navigator—or primary care nurse ‘bridge’—to connect primary care and mental healthcare services.37 A network of ‘gateway services’ was also tested in Canada using a ‘Reception House’ model.35 These services are characterised by being person-centred, interprofessional, communication-focused and comprehensive across the continuum of care.35 Relationship management between the Reception House, health professionals, translation services and social services was acknowledged as a key component for success.35 Input from international medical graduates in training also supported this work by enhancing culturally appropriate service delivery by this network of partners.35

Table 3.

Enabling strategies present across studies

| Strategy | Studies | ||||||

| Host community engagement | Calvo et al 30 | ||||||

| System navigation | Calvo et al 30 | Kim et al 36 | McMurray et al 35 | Woodland et al 39 | Yeung et al 37 | Lilleston et al 28 | |

| Integrated health and social services through networked approach | Catarci34 | Kim et al 36 | McMurray et al 35 | Yeung et al 37 | |||

| Translation support | Kim et al 36 | MacFarlane et al 33 | McMurray et al 35 | McNaughton et al 24 | Woodland et al 27 | Cowell et al 25 | Guruge et al 29 |

| Active case finding/outreach | McNaughton et al 24 | Verhagen et al 26 | Woodland et al 27 | Guruge et al 29 | |||

| Refugee-specific service delivery and access to health and social networks | Mortensen31 | Philbin et al 40 | Stewart et al 32 | Verhagen et al 26 | |||

| Legislative support | Philbin et al 40 | Tuepker and Chi41 | Woodland et al 39 | Geltman and Cochran38 | |||

| Changes in funding modalities | Tuepker and Chi41 | ||||||

Striking a balance between providing tailored, culturally appropriate care and integrating health and social services for refugees into existing services in the host community can be especially challenging. Policy reviews suggest that taking a ‘one-policy, one-level, one-outcome’ approach or focusing refugee management under one ministry is not sufficient in addressing the wide range of obstacles that both host and refugee communities are facing as a result of the current political climate.40 41 The Ethiopian government, for example, had success in reorganising ministries to incorporate refugee management into existing portfolios rather than a refugee-specific one, moving refugee assistance programmes out of camps and promoting more collaboration across government and non-governmental programmes.41

In terms of stakeholders involved (research question 3) in implementing, monitoring or facilitating the aforementioned strategies, studies did not always report on the parties involved in governance, financing, planning, service delivery, monitoring and evaluation or demand generation (elements drawn from the integration framework by Atun et al.21 Where they were mentioned, stakeholders responsible for the governance of interventions addressing refugee health were composed of primary care centres,35 37 municipal governments,30 38 departments of social services and/or public health,30 36 central services responsible for coordination of refugee services and provision of assistance to local services,34 35 national governments31 32 and international bodies.28 Stakeholders responsible for health financing consisted of individual fundraising by service providers,31 33 government30 31 35 38 41 and international bodies or donors.1 28 36 37Programme and policy planning stakeholders encompassed national governments,31 38 41 departments of social services and/or public health,27 30 36 central services responsible for coordination of refugee services and provision of assistance to local services,29 34 35 researchers,24 26 30 36 37 service providers27 28 35 37 and international bodies or donors.28 36 41 Service delivery stakeholders included national departments of social services and/or public health,27 30 33 36 38–41 networks of local service providers in health, education, socialisation, translation and/or employment,24 31 34 36 healthcare providers,27 33 35 37 38 central services responsible for coordination of refugee services and provision of assistance to local services,32 34 35 community health workers26 and international bodies.28 41 Stakeholders responsible for monitoring and evaluation were seldom explicitly mentioned. For demand generation, stakeholders included central services responsible for the coordination of refugee services and provision of assistance to local services,35 local media in the language of the target population,36 community leaders and/or community health workers,26 28 31 32 home health outreach services28 31 and healthcare providers.33 37

Discussion

The findings from the existing but scarce literature highlight critical factors necessary in facilitating intersectoral collaboration and the successful integration of refugee services within existing health systems. The three research questions studied demonstrated barriers and facilitators, enabling strategies recorded in the literature and the stakeholders involved. This section will summarise key themes across these topics and discuss implications for programme implementation, policy and future research.

Coordination of existing public and private services

A networked approach to service delivery during the initial reception of refugees can often mitigate some of the difficulties encountered by refugee communities. Some examples of coordination of services were seen in Italy,34 Australia,27 the USA37 and Canada.35 In Canada, where a network of ‘gateway services’ was tested using the ‘Reception House’ model, it successfully provided responsive and culturally sensitive primary care.35 By partnering community and translation services, as well as healthcare providers with the Reception House, it decreased wait times and improved healthcare access through referrals and coordination of services.35 Further analysis with costing studies on a tailored package of health services for vulnerable populations could help to support improved financing of efforts to coordinate services across sectors.

Introduction of a system navigator role

Integration works through establishing relationships across networks of local stakeholders and service providers. To coordinate this effectively, a system navigator role can be established—the evidence suggests that this role is most effective in the early stage of resettlement.35 The system navigation role can be played by an organisation or by people within the existing health or social systems. It connects incoming refugees to timely, culturally appropriate care in the community without creating parallel structures that either threaten host communities or further stigmatise refugees.30 35 The likelihood of success of a system navigator role is further strengthened when providers have access to the knowledge, tools and training needed to address the specific needs of refugees, including the more vulnerable subgroups (eg, the elderly, women and children). Providers need to understand the context in which they work and the available features and services, user needs, and legislation as it relates to refugees.34 Those playing a coordination or system navigation role should also be able to build strong networks with allied specialists, identify appropriate resources and reach out to users.34 35 The risk here, however, is that integrating refugee care may eliminate some determination procedures, potentially undermining the protection mandate and underestimate the tailored needs of refugees dealing with significant trauma.41 Future research on the required competencies of the system navigator role is needed to ensure that appropriate professionals are recruited and trained.

Advocacy and legislative support

Exclusionary immigration policies can play a considerable role in marginalisation and discrimination against refugee communities leading to decreased health-seeking behaviours and use of available integrated or intersectoral services.40 Effective advocacy needs to target the policy-making levels in order to counteract the negative impacts of exclusionary policies. Advocacy by healthcare providers can be influential at the institutional level to push for better allocation of services and funding.31 A multipronged approach may be necessary to continue to advocate for the right to health for refugees by addressing legal challenges, establishing timely and accurate data and information systems to capture needs, creating health promoting environments, investing in person-centred, culturally appropriate and easily accessible services, and evaluating coordination and service delivery efforts. Engaging policy-makers in knowledge translation and evidence-informed decision-making is one way to effectively advocate and provide legislative support in refugee health. In Lebanon, for example, where there are huge demands in meeting the health needs of a large Syrian refugee population, researchers engaged policy-makers in knowledge production (ie, research priority-setting), translation and uptake activities.42 This ultimately led to the hiring of a refugee health coordinator by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health. The refugee health coordinator role functioned to support intersectoral collaboration, assisting in strategic planning and implementation of action plans to respond to the health needs of Syrian refugees including helping with the development of refugee health information systems at the Ministry of Public Health.42 The UCL-Lancet Commission on Migration and Health also supports knowledge translation by bringing together academics, policy-makers and health system experts to take an interdisciplinary approach to reviewing evidence, develop policy recommendations and disseminate these findings globally among policy-makers and institutions.43

Alternative models of care to reach vulnerable women and children

Among the studies that reported targeted interventions for women and children, alternative models of care were used. This included mobile health clinics, and programmes linked to schools to support screening and active case finding. These alternate models increased accessibility of essential health services, increased detection of health conditions and improved coordination of care, and reduced feelings of social isolation.27 28 This suggests that flexible service delivery and innovation in mode of delivery should be considered when attempting to reach at risk refugee groups. Better collection and use of evidence on the needs of vulnerable refugee subgroups and how to target them are essential next steps to design appropriate service delivery models.

Policy insights

From the available evidence, the following are policy insights to inform greater integration of services and/or intersectoral collaboration. These recommendations are based on consistent facilitators and barriers identified across studies included in this review. They are critical starting points in enhancing programmes to better serve refugees while promoting efficiency in health systems.

Strengthening the coordination between existing programmes through financing stronger referral systems and colocation of services.

Incentivising health and social service authorities to establish and finance formal system navigator roles that connect all relevant services–provision of information technology tools can help support this function and better manage the network of available programmes.

Engaging host communities to enhance understanding, reduce stigma and to create an enabling environment for policies that protect refugees and their rights to social determinants of health.

Communicating the availability of programmes and services through cultural mediators and establishing formal translation and transport services to improve access.

Establishing training and resources for providers to (A) better understand the needs of refugee communities, (B) be aware of available and relevant services for referral across sectors and (C) more efficiently manage cases.

Limitations and future directions

Our review was limited by the scarcity of evidence in this area. Due to this, all relevant studies were included, therefore, quality and rigour may vary. Some key programmes and approaches may be missing due to interventions occurring at the individual level instead of at the systems level, as well as not having been published in academic literature. Individual health providers or organisations will navigate barriers in health systems through tacit and experiential knowledge that is often not documented. Data will be further amplified by conducting key informant interviews in selected countries.

As others have noted, the literature on intersectoral collaboration disproportionately focuses on high-income countries.44 It is, therefore, no surprise that the evidence for this review largely came from high-income countries with only two studies conducted in upper-middle income and two in low-income countries. This may affect the generalisability of the findings reported here as low-income and middle-income countries have greater coordination challenges to overcome due to fragmented systems and weak governance.45 Additionally, according to the latest report from the United Nations Refugee Agency, approximately 85% of refugees are hosted in developing nations.46 More evidence and special consideration is needed in these contexts with respect to refugee health, particularly for those most at risk subgroups such as women, children and the elderly.

Although there exists reaffirmed enthusiasm in intersectoral approaches to achieving global health agendas such as the SDGs, it has been found that the lack of quality evidence represents an essential hurdle to evidence-informed decision-making for the development of cross-cutting policies and governance required for sustained intersectoral collaboration.44 This pattern of a dearth of evidence was seen in our review. Additionally, most of what has been written has not been grounded in relevant theories or frameworks.45 Our use of frameworks to structure our analysis is a step forward in addressing this issue. Generating high-quality data in health systems and policy research for migrant health and on intersectoral approaches has been identified as a research priority.44 47 Future research should, therefore, also consider the structured evaluation of evidence through a frameworked approach.

Conclusion

Refugees experience individual, institutional and system-level obstacles when seeking healthcare. To ensure adequate health services tailored to this vulnerable population, conducting research and gathering quality evidence on integrated and intersectoral approaches is a top priority. This scoping review has highlighted important gaps in current knowledge and made suggestions for future research relevant to key themes.

Our findings indicate that policies aiming at integrating services and fostering intersectoral action should consider system-level approaches such as the colocation of services, transportation support and establishing system navigator roles. Communication challenges due to language barriers should also be addressed with a view of providing culturally sensitive programmes. There is also a need to strengthen the capacities of front-line providers and managers, to improve their knowledge of available services as well as their ability to provide care to specialised vulnerable groups such as refugees. Engaging host communities around a human rights-focused strategy to the health of refugees is also fundamental to address discrimination and stigma. Current gaps in knowledge found in our study represent an untapped potential for improvements to financial and human resource efficiency in health systems. Given the limited evidence, we found in our scoping review, the momentum for continued research should be sustained.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Karolinska Institutet librarians, Magdalena Svanberg and Gun Brit Knutssön, for their contributions, specifically in running the search and identifying appropriate databases. We are also grateful to WHO Euro for their discussions and suggestions in the early stages of this project.

Footnotes

Contributors: GT together with librarians at Karolinska Institutet identified databases and planned the literature search. SH and DJ drafted the paper and incorporated coauthor feedback, SH and DJ abstracted data from peer-reviewed literature. SC, EVL, GT and PF provided critical feedback and comments on the manuscript. SC and SH acted as secondary reviewers.

Funding: No funding was obtained for this project. In-kind time contributions from staff at the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research and SIGHT have made this possible.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was not required for this scoping review as human subjects are not involved.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. OHCHR. The Right to Health. Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tangcharoensathien V, Mills A, Palu T. Accelerating health equity: the key role of universal health coverage in the Sustainable Development Goals. BMC Med 2015;13:101 10.1186/s12916-015-0342-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. UNHCR. Convention and Protocol relating to the status of refugees. Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4. UNHCR. UNHCR viewpoint: ‘Refugee’ or ‘migrant’ – Which is right? Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Ingleby D, et al. . Migration and health in an increasingly diverse Europe. Lancet 2013;381:1235–45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62086-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Council for the EU. Council Directive 2003/9/EC of 27 January 2003 Laying Down 453 Minimum Standards for the Reception of Asylum Seekers in Member States. Off J Eur Union 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7. OHCHR. General Recommendation 30. Discrimination against non-citizens. Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jackson-Bowers E, Cheng I-H. Meeting the primary health care needs of refugees and asylum seekers. Res Roundup 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gostin LO, Magnusson RS, Krech R, et al. . Advancing the Right to Health-The Vital Role of Law. Am J Public Health 2017;107:1755-1756 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Joshi C, Russell G, Cheng IH, et al. . A narrative synthesis of the impact of primary health care delivery models for refugees in resettlement countries on access, quality and coordination. Int J Equity Health 2013;12:88 10.1186/1475-9276-12-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Citizenship AGD of I and. Fact sheet 60 - Australia’s refugee and humanitarian program, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12. UN. Integrated Approaches to Sustainable Development Planning and Implementation. New York, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kett ME. Internally displaced peoples in Bosnia-Herzegovina: impacts of long-term displacement on health and well-being. Med Confl Surviv 2005;21:199–215. 10.1080/13623690500166028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patel N, Kellezi B, Williams AC. Psychological, social and welfare interventions for psychological health and well-being of torture survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;11:CD009317 10.1002/14651858.CD009317.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. . A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:15 10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. . The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ manual: methodology for JBI scoping review. Adelaide, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Center for Open Science. Open science framework. https://osf.io/

- 19. Javadi D, Langlois EV, Ho S, et al. . Intersectoral approaches and integrated services in achieving the right to health for refugees upon resettlement: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016638 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Walt G, Shiffman J, Schneider H, et al. . ’Doing' health policy analysis: methodological and conceptual reflections and challenges. Health Policy Plan 2008;23:308–17. 10.1093/heapol/czn024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Atun R, de Jongh T, Secci F, et al. . Integration of targeted health interventions into health systems: a conceptual framework for analysis. Health Policy Plan 2010;25:104–11. 10.1093/heapol/czp055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. WHO. Health in all policies: framework for country action. Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McNaughton DB, Hindin P, Guerrero Y. Directions for refining a school nursing intervention for Mexican immigrant families. J Sch Nurs 2010;26:430–5. 10.1177/1059840510381594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cowell JM, McNaughton D, Ailey S, et al. . Clinical Trial Outcomes of the Mexican American Problem Solving Program (MAPS). Hisp Heal Care Int 2009;7:178–89. 10.1891/1540-4153.7.4.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Verhagen I, Ros WJ, Steunenberg B, et al. . Culturally sensitive care for elderly immigrants through ethnic community health workers: design and development of a community based intervention programme in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2013;13:227 10.1186/1471-2458-13-227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Woodland L, Kang M, Elliot C, et al. . Evaluation of a school screening programme for young people from refugee backgrounds. J Paediatr Child Health 2016;52:72–9. 10.1111/jpc.12989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lilleston P, Winograd L, Ahmed S, et al. . Evaluation of a mobile approach to gender-based violence service delivery among Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Health Policy Plan 2018;33:767–76. 10.1093/heapol/czy050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guruge S, Hunter J, Barker K, et al. . Immigrant women’s experiences of receiving care in a mobile health clinic. J Adv Nurs 2010;66:350–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05182.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Calvo R, Rojas V, Waters MC. The effect of universal service delivery on the integration of moroccan immigrants in Spain: a case study from an anti-oppressive perspective. Br J Soc Work 2014;44:i123–i139. 10.1093/bjsw/bcu047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mortensen A. Public health system responsiveness to refugee groups in New Zealand: activation from the bottom up. Soc Policy J New Zeal 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stewart M, Anderson J, Beiser M, et al. . Multicultural meanings of social support among immigrants and refugees. Int Migr 2008;46:123–59. 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2008.00464.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Macfarlane A, Singleton C, Green E. Language barriers in health and social care consultations in the community: a comparative study of responses in Ireland and England. Health Policy 2009;92:203–10. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Catarci M. Conceptions and strategies for user integration across refugee services in Italy. J Educ Cult Psychol Stud 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35. McMurray J, Breward K, Breward M, et al. . Integrated Primary Care Improves Access to Healthcare for Newly Arrived Refugees in Canada. J Immigr Minor Health 2014;16:576–85. 10.1007/s10903-013-9954-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim MJ, Cho HI, Cheon-Klessig YS, et al. . Primary health care for Korean immigrants: sustaining a culturally sensitive model. Public Health Nurs 2002;19:191–200. 10.1046/j.0737-1209.2002.19307.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yeung A, Kung WW, Chung H, et al. . Integrating psychiatry and primary care improves acceptability to mental health services among Chinese Americans. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004;26:256–60. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Geltman PL, Cochran J. A private-sector preferred provider network model for public health screening of newly resettled refugees. Am J Public Health 2005;95:196–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.040311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Woodland L, Burgner D, Paxton G, et al. . Health service delivery for newly arrived refugee children: a framework for good practice. J Paediatr Child Health 2010;46:560–7. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01796.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Philbin MM, Flake M, Hatzenbuehler ML, et al. . State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2018;199:29–38. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tuepker A, Chi C. Evaluating integrated healthcare for refugees and hosts in an African context. Health Econ Policy Law 2009;4:159–78. 10.1017/S1744133109004824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Langlois E V, Daniels K, Akl EA. Evidence synthesis for health policy and systems: a methods guide. Geneva, Switzerland 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. The UCL-Lancet Commission on Migration and Health. 2018.

- 44. Glandon D, Meghani A, Jessani N, et al. . Identifying health policy and systems research priorities on multisectoral collaboration for health in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000970 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bennett S, Glandon D, Rasanathan K. Governing multisectoral action for health in low-income and middle-income countries: unpacking the problem and rising to the challenge. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000880 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. UNHCR. Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2017. Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. https://www.unhcr.org/5b27be547.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 47. Abubakar I, Aldridge RW, Devakumar D, et al. . The UCL-Lancet Commission on Migration and Health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet 2018;392:2606–54. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029407supp001.pdf (74.9KB, pdf)