Abstract

Purpose

HELMi (Health and Early Life Microbiota) is a longitudinal, prospective general population birth cohort, set up to identify environmental, lifestyle and genetic factors that modify the intestinal microbiota development in the first years of life and their relation to child health and well-being.

Participants

The HELMi cohort consists of 1055 healthy term infants born in 2016–2018 mainly at the capital region of Finland and their parents. The intestinal microbiota development of the infants is characterised based on nine, strategically selected, faecal samples and connected to extensive online questionnaire-collected metadata at weekly to monthly intervals focusing on the diet, other exposures and family’s lifestyle as well as the health and growth of the child. Motor and cognitive developmental screening takes place at 18 months. Infant’s DNA sample, mother’s breast milk sample and both parent’s spot faecal samples have been collected.

Findings to date

The mean age of the mothers was 32.8 (SD 4.1) and fathers/coparents 34.8 (5.3) years at the time of enrolment. Seventeen percentage (n=180) of the infants were born by caesarean section. Just under half (49%) were firstborns; 50.7% were males. At 3 months of age, 86% of the babies were exclusively breastfed and 2% exclusively formula-fed.

Future plans

The current follow-up from pregnancy to first 24 months will be completed in March 2020, totalling to over 10 000 biological samples and over 50 000 questionnaire entries. The results are expected to identify environmental and host factors that affect early gut microbiota development and health, and hence give indications of how to prevent or reverse microbiota perturbations in infancy. This prospective cohort will be followed up further to identify how the early microbiota relates to later health outcomes, especially weight gain, infections and allergic and other chronic diseases.

Trial registration number

NCT03996304; Pre-results.

Keywords: birth cohort, paediatrics, intestinal microbiota development, early life exposures, longitudinal follow-up

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large, prospective microbiota-focused birth cohort: frequent intestinal microbiota sampling, parental faecal and maternal milk samples and offspring’s DNA sample are used to study the individual determinants, rate and patterns of microbiota colonisation and succession during the first 2 years of life.

Longitudinal metadata collection enables to characterise how early exposure patterns may modify the microbiota development and how that relates to symptoms and health outcomes in genotype-specific manner.

Clinical phenotyping during the first 2 years is primarily based on parents’ reports, complemented by Bayley Scales test of Infant Development and possibility to extract healthcare and drug purchase data from national registries.

Allergic and other immune-mediated diseases are modestly over-represented among the parents, predicting high phenotypic variation among the study children already at early age.

Parents from all educational attainment categories are represented with a skew towards those with a higher education.

Introduction

During the perinatal period, broadly defined as the first 1–2 years after birth, the newborn undergoes rapid growth and development including that of the immune system.1 In parallel, infants are colonised by symbiotic gut microbes acquired from the immediate environment that are selectively promoted by host and environmental factors to reach an individual-specific community.2 The early-life microbiota is now being recognised as an important factor for long-term human health and development, contributing to the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease.3 Early microbial stimuli have a central role in directing the development of the immune system4 5 as well as in metabolic programming.6 Rodent experiments indicate a presence of relatively narrow postnatal time period during which the immune system is permissive to microbial instruction,6 7 underscoring the importance and durable effects of the initial colonisation.

Due to the importance of the early life microbiota to lifelong health, several prospective birth cohort studies investigating gut microbiota composition in early life have been undertaken.8–13 However, the Health and Early Life Microbiota (HELMi) cohort is the first to couple frequent faecal microbiota sampling to exhaustive collection of longitudinal metadata on the lifestyle, environmental exposures and health of the infants and their family, achieved by interactive web-based questionnaires that parents fill up to weekly intervals throughout the extended perinatal period from pregnancy to 2 years postpartum.

With the HELMi cohort, we aim to identify novel links between the intestinal microbiota development, environmental and genetic factors and health outcomes. In this paper, we describe the design of the cohort as well as the sample and data collection procedures. Furthermore, we present summary characteristics of the infants and their parents, focusing on perinatal factors that are known to strongly affect early microbiota development.

Cohort description

Study purpose

The HELMi study is a longitudinal cohort designed to identify links between the intestinal microbiota development, environmental and genetic factors and health outcomes. The current establishment of the cohort covers follow-up over the first 2 years of life; however, the cohort will be followed up as long as possible to assess the relation of early microbial and environmental factors to infectious and chronic diseases, overweight and obesity development as well as cognitive performance.

Recruitment

Pregnant women with singleton gestation were recruited from the general population mainly in the capital region of Finland. Three methods were used to recruit participants: (1) displaying recruitment posters and flyers on the antenatal clinics within the public healthcare system; (2) directly approaching potential participants at the antenatal clinics and perinatal ultrasound screens and (3) advertising the study on social media. Healthy term babies born on gestational weeks 37–42 without known congenital defects were included in the study. At least one parent in each family had to be Finnish speaking as extensive questionnaires form an integral part of the study.

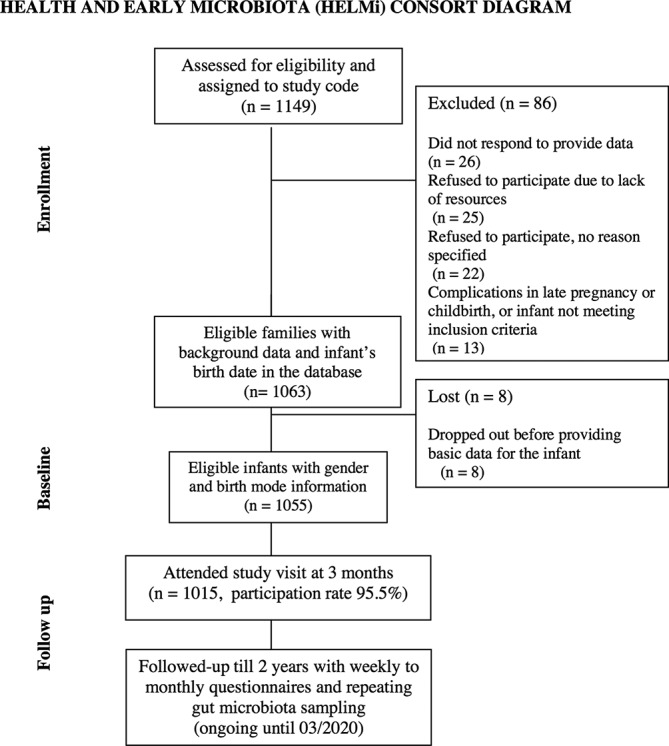

A total of 1587 families expressed interest in participating in the HELMi study during the recruitment period (February 2016–March 2018). Out of the 1149 consented families, 86 families either withdrew from the study before the childbirth or were excluded due to preterm birth or birth defect (figure 1). Altogether 1063 infants fulfilling the inclusion criteria were born, of which 1055 completed the data for childbirth details and infant gender. Study retention was 96.2% at the age of 3 months. At the time of writing, in early March 2019, when the youngest study children were 12 months, the retention rate was 91.7% (n=967).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram.

Data collection

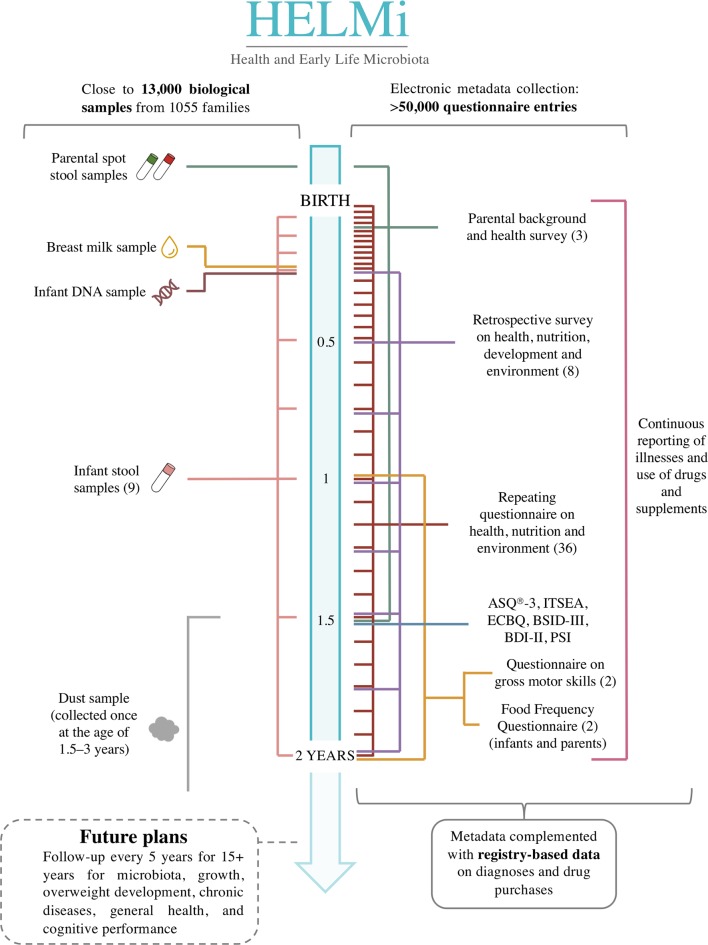

Overview of the HELMi cohort data repository for the first 2 year period is provided in figure 2 and described in detail below. For each sample type, the currently ongoing analyses are indicated.

Figure 2.

Infographic illustrating the type and frequency of biological samples and questionnaires collected in the HELMi cohort during the first 2 years. Each horizontal line depicts sample and data collection point in relation to age that is indicated on the central bar. The colours refer to the type of sample or data collected, the numbers in the parenthesis to the total number of entries per family. ASQ-3, Ages & Stages Questionnaires, Third Edition; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory II; BSID-III, Bayley Scale of Infant Development III; ECBQ, Early Childhood Behaviour Questionnaire; ITSEA, Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment; PSI, Parenting Stress Index.

Biological samples

Stool samples: Nine stool samples from the infants are collected at the age of 3, 6, 9, 12 weeks and 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months. In addition, for a subset of 66 infants, daily sampling was performed during the 1st, 6th and/or 12th month as part of a HELMiPlus subproject. Parents were asked to provide a spot stool sample around the time of childbirth, preferably within 2 weeks of the due date. Parents collect the faecal samples at home, freeze them immediately at −20°C and transport in a frozen form to the laboratory for −80°C storage. Faecal samples are processed for the intestinal microbiota analysis using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing.

Breast milk sample: Breastfeeding mothers were requested to give a breast milk sample at 3 months postpartum at the clinic. Mothers gave a milk sample by hand expression from an uncleaned breast from which they had not fed for a minimum of 1 hour. When needed, the nurse assisted the expression aseptically. The first 0.5 mL was discarded after which a 1 mL sample was collected in a chemically clean cup and transferred to freezing phial aseptically. Samples were temporarily stored at −20°C before transfer to −80°C.

DNA sample: Buccal swabs from the infants were collected at 3 months for the extraction of genomic DNA. All children are being genotyped for FUT2 gene that determines whether mucosal glycans contain terminal fucose-sugar residues that are known to mediate interactions between gut microbes and the host, FUT2 representing the first single gene variant that was associated to microbiota composition in humans.14 FUT2 genotyping is performed in collaboration with the Finnish Red Cross using a previously described single nucleotide polymorphism analysis method.14

Questionnaires

We collect a large amount of data on the families’ lifestyle, environmental exposures and the health of the study infants and their parents using online questionnaires that store the answers instantly on an online database, enabling monitoring and data query already during the data collection. After providing basic information on the neonate, including the birth date, gender, gestational age and birth weight, parents were prompted to fill in recurring questionnaires on child’s nutrition, gut function and care practices weekly for the first 4 months, then biweekly until 7 months and finally monthly until 2 years of child’s age (figure 2). In addition, parents fill in comprehensive questionnaires regarding living conditions and infant behaviour and health at 3 month intervals. At child’s age 1 and 2, additional questionnaires on diet and motor development are administered. The start and end date for illnesses, medication and use of probiotics and other dietary supplements are reported in a continuous manner using a study diary. To promote compliance in the questionnaire response rates, parents receive automatic reminders via email and text messages.

Nutrition: Breastfeeding and use of infant formula are monitored at weekly to monthly frequency, with an estimate of percent-based and volume-based share of formula in partially breastfed infants before weaning. For the first 7 months, parents indicated at weekly to biweekly intervals for breastfed infants whether they received the milk from the breast or whether it was pumped. We record data on timing and type of introduced solid foods and monitor which food ingredients are intentionally avoided. At child’s age 1 and 2, parents fill food frequency questionnaires for the infant and themselves. Families that collected daily faecal samples from the infant as part of the HELMiPlus subproject also filled a daily food diary for the infant.

Growth: Weight and height trajectories are recorded based on the 12 measurements taken at child welfare clinic during the first 24 months, according to the Finnish public health system.

Health and well-being: Infants’ crying, gastrointestinal function (based on questions, eg, on regurgitation, stool frequency, consistency and colour, signs of stomach ache and flatulence) and skin health are monitored with the recurring questionnaires. Child’s sleeping habits, onset of allergic or other symptoms, need for healthcare services and medical diagnoses set by a physician are reported at 3-month intervals.

Environment and lifestyle: In addition to nutrition, the recorded environmental exposures for the study infants include person-to-person contacts (number of siblings and frequent caregivers; group size, if in day care) and environmental factors (housing type, biodiversity, pets, travelling, home cleaning practices and hygiene standards measured based on, eg, on the frequency of vacuuming and sterilisation of dummies, if in use).

Maternal and paternal factors: Age, education, smoking and alcohol use were recorded for both parents at the enrolment; weight and height for body mass index (BMI), medical diagnoses and family history of chronic diseases were assessed for mothers and biological fathers. For the mother, several prenatal and postnatal factors were additionally assessed, including parity, medication and use of probiotics and other supplements during pregnancy and lactation, complications of pregnancy and childbirth details. Maternal stress during the third trimester was determined using a short scaling questionnaire on stress. The same questionnaire is administered at 1.5 years postpartum, together with Beck Depression Inventory II and Parenting Stress Index questionnaires.

Developmental, psychological and cognitive assessments

Child’s gross motor skills are assessed with questionnaires filled at 1 and 2 years. The fine motor skills as well as cognitive and social skills are evaluated at 18 months with the following standardised questionnaires: Ages & Stages Questionnaires, Third Edition, Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment and Early Childhood Behaviour Questionnaire. In addition, cognitive, fine motor and language development is assessed by a psychologist at 18 months of child’s age using the Bayley Scale of Infant Development III for at least 500 infants randomly selected from the cohort.

Registry-based data

As previously,15 we will use registry-based antibiotic purchase and chronic illness data as exploratory and response variables for the microbiota readouts to complement parents’ self-reported medical information from the prenatal and postnatal period. We will exploit the national healthcare and drug purchase registries including the Finnish Medical Birth Register and the comprehensive Drug Purchase Registry (maintained by the Social Insurance Institution, Kela) that provides the history of antibiotics and other drugs purchased on prescriptions. Current ethical approval covers periods from birth to 2 years for the child and 5 years preceding the childbirth for the mother. Selected chronic conditions, such as atopy, inflammatory bowel disease and coeliac disease, entitle a person to a special reimbursement of the medication when the specified criteria are to be met and approved by a physician. Hence, the registry data can be used to verify the self-reported physician diagnoses.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the design or conduct of this study. The study participants have been offered the opportunity to join a closed Facebook group where they can present questions to each other as well as to the research team and give feedback about the study. Study updates are regularly shared with the participants through email newsletters. Additionally, approximately once a year, the participants are invited to a webinar, where the researchers discuss the study in a broader context and answer questions. After filling the recurring questionnaires, the parents are provided with instant feedback graphics summarising selected answers in respect to time and those of the other participant families. After completing the 2 year participation, the parents can save all the data they provided for their own records. After completion of the intestinal microbiota analyses, the parents will receive information of the microbiota composition of their child.

Findings to date

Baseline characteristics

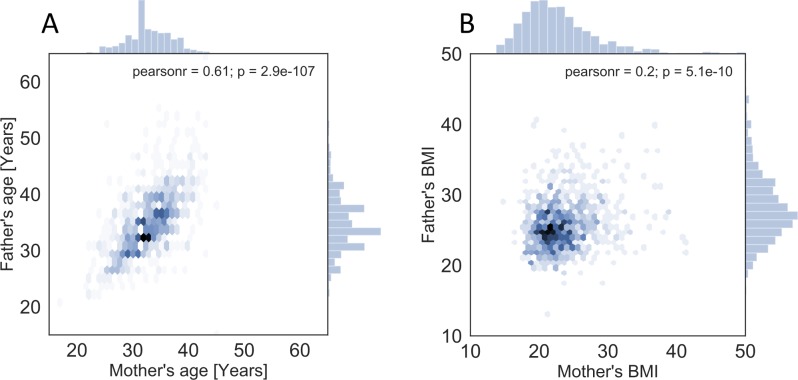

At enrolment, 97.3% of the participating families were nuclear families with two biological parents, 1.4% heterosexual or homosexual couples where the partner was not a biological father of the infant and 1.3% single mothers. The basic characteristics of all parents are presented in online supplementary table 1. Demographic and anthropometric data were collected only for biological parents (online supplementary table 2). Altogether 88% of the study families lived in the capital region, 11.7% in the larger metropolitan area and 3.9% elsewhere in Finland. The most common housing type was apartment (56%); 27% of the families lived in semidetached houses and 17% lived in detached houses with a garden. The mean age of the mothers was 32.8 (SD 4.1) and fathers 34.8 (5.3) years at the time of enrolment. Most parents were normal weight; mothers’ mean prepregnancy BMI was 23.4 (SD 3.7) and fathers’ 25.7 (3.4). Within a family, both age and BMI correlated significantly between the spouses (figure 3A,B).

Figure 3.

Parent’s age (A) and BMI (B) distribution and their correlation between the parents within a family. Data are plotted on hexagonal bins, which are shaded according to the count of the data points in the aggregate. In addition, histograms of the maternal and paternal values are plotted on the top and right, respectively. BMI, body mass index.

bmjopen-2018-028500supp001.pdf (53.2KB, pdf)

The educational attainment of the parents was recorded as enrolment statistics. For the HELMi mothers (n=1063), the highest level of educational attainment was 57.6% university, 30.3% university of applied sciences, 7.3% vocational school, 3.9% upper secondary school and 0.9% secondary school. Among the fathers and other coparents (n=1063), the maximum level of educational attainment was 49.5% university, 23.2% university of applied sciences, 16.5% vocational school, 7.0% upper secondary school and 2.4% secondary school (for 1.4% data not available). Parents with a degree from an academic university or a university of applied sciences were over-represented in our cohort (1.7 times higher prevalence than in the wider capital region population aged 30–34 in 2016). Similarly, parents with no education beyond secondary school were under-represented (14.3 times lower prevalence than in the wider capital region population aged 30–34 in 2016).16

Parents’ health

Overall, 57% of the mothers and 45% of the biological fathers self-reported at least one medical diagnosis (online supplementary table 2). The most abundant diagnosis was ‘allergy’, which was reported by 38% of the mothers and 31% of the fathers. Other common diagnoses included ‘atopy’ (11% for mothers and 5% for fathers), ‘asthma’ (9% and 5%, respectively) and ‘irritable bowel syndrome’ (6% and 2%, respectively). The prevalence of allergic diseases in the general population of Finland is comparable except for the maternal asthma which was circa 1.7 times higher in the cohort.17 18 Inflammatory bowel disease and coeliac disease were both reported by 2% of the mothers and in 2% and 1% of the fathers, respectively. The prevalence of diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease is 0.9% in the whole Finland19 and of coeliac disease 0.7% for women and 0.4% for men living in the Southern Finland.20 Hence, these gastrointestinal diseases were diagnosed 2.5-fold to 3-fold times more frequently among the parents of the cohort than in the general population. Pregnancy complications were diagnosed in 26% of the mothers. These included gestational diabetes (19%), hypertension (3%), intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (2%), hypothyroidism (1%) and pre-eclampsia (1%). The prevalence of gestational diabetes in the study population (19%) matches that of the general population.21

Infants

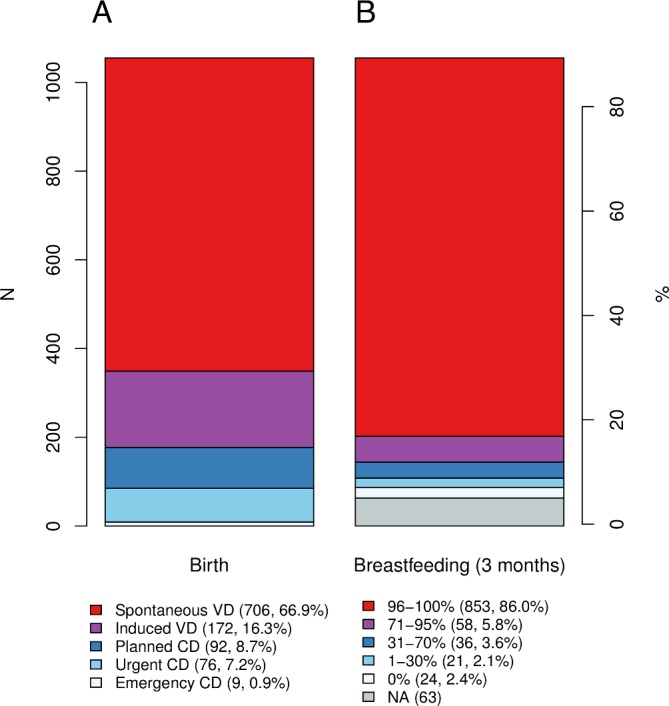

The 1055 study infants (51% boys) were born between March 2016 and March 2018. The time of gestation ranged from 37 to 43 weeks, mean 39.8 weeks (SD 4.4). The vast majority (98%) of the babies were born in hospitals and 1% (n=10) at home or in a car. Average birth weight was 3558 g and average height was 51 cm. Circa half (49%) of the infants were firstborns, 82% were born vaginally and 17% via caesarean section (CS), reflecting accurately the general rate of CS births in Finland (16.7% in 2017).21 The CS births comprised 76 elective, 91 urgent and 9 emergency operations (figure 4A; an ‘urgent CS’ is a non-scheduled CS without an immediate threat to the life of either the mother or fetus, in contrast to an ‘emergency CS’). In Finland, intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is administered in all CS deliveries and in vaginal deliveries in the case of a positive screening result for vaginal Group B Streptococcus (GBS) or other risk factors for neonatal GBS disease.22 Among vaginal births, 25% of the mothers reported prophylactic intrapartum antibiotic administration.

Figure 4.

(A) Infant birth mode (VD; CD) and (B) breastfeeding rates at 3 months in the HELMi cohort. CD, caesarean delivery; VD, vaginal delivery.

Breastfeeding rates at 3 months are presented in figure 4B. At 3 months (n=992), 86% of the infants were exclusively or almost exclusively breastfed (96%–100% of the diet consisting of breast milk) and 2% (n=24) were exclusively formula-fed. Based on retrospective reporting at 12 months of age (n=910), 86% of the infants had been exclusively breastfed (defined as 100% of diet consisting of breast milk) for at least the first 3 months. Hence, at 3 months of age, exclusive breastfeeding was 1.5–2.6 times more common in this cohort (86%) than generally in Finland,23 24 although the available references date back to over a decade and may not reflect the current situation. Moreover, our definition for exclusive breastfeeding is more liberate than that of the WHO followed by the reference studies as we did not control for administration of water. As many as 70% of the infants were given probiotic products by the age of 3 months. Hence, HELMi cohort is very well positioned to study the combinatorial effects of the known early exposures on the gut microbiota development and health and to identify further environment and host-related factors that can either potentiate or reverse these.

Stool samples

By March 2019, ca. 1600 and 7200 stool samples from the parents and infants have been collected and returned to the university, respectively. The return rate of parental faecal sample was 88% (n=927) for the mothers and 63% (n=668) for the fathers and other coparents. For the first 275 families who completed the study protocol by the end of 2018, a mean of 8.9 (SD 0.5) out of the nine infant faecal samples were received. We are currently in the process of carrying out the microbiota analyses using 16S RNA gene and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) amplicon sequencing for the total microbiota and species-level analysis of bifidobacteria,25 respectively.

Future plans

We are now in the phase of accumulating microbiota samples and metadata during the first 2 years of life of the study children. For the gut microbiota, analyses will be expanded from the compositional analysis to shotgun metagenomics to enable strain-level analysis for the vertical transfer of the microbiota both from the mother and the father as well as functional microbiome analysis. Furthermore, we will extend the host genomic analysis from single genes to genome-wide analysis, and the stool-based analyses from the microbiota to host-derived gut health markers. The breast milk samples will be analysed for their human milk oligosaccharides content. As part of a separate but highly interlinked project, the questionnaire-based environmental exposure analysis will be complemented by collection of home dust samples, which will be analysed for bacterial 16S rRNA gene and fungal ITS amplicon sequencing and possibly for quantitative PCR and microbial toxin analysis as previously described.26 The dust samples are collected once at the child’s age of 1.5–3 years and coupled to questionnaire collecting specific data on the type of housing, building materials, ventilation system and so on.

After this 2-year establishment period, the HELMi prospective cohort will continue to collect growth and health outcomes, gut microbiota and other biological samples as well as data on the main microbiota-affecting exposures, such as diet and antibiotics periodically. We plan to organise a follow-up every 4–5 years for 15+ years, depending on the available funds. The outcomes at focus include growth, overweight and obesity development, infections, allergic and other chronic diseases as well as cognitive performance. Some forthcoming analyses are likely to be targeted for specific participant groups (eg, antibiotic-exposed or overweight and obese children), who could be selected based on the current or latest phenotype and their early-life growth or specific exposure that enables focusing on early markers of disease.

Acknowledgments

The study nurses, especially Jaana Valkeapää and in addition Heli Suomalainen, Anna Mantere, Eevi Heitto and Janica Bergström are acknowledged for the recruitment and sample and data collection.

Sari Toivonen and Pekko Huuskonen are thanked for the support they provided for the recruitment and Roosa Jokela for help with the article figures. Tinja Kanerva is thanked for laboratory management and together with Jessica Manngård and Ching Jian for sample processing. PikkuJätti medical centres at Tapiola, Itäkeskus and Myyrmäki are acknowledged for offering the premises for study visits and the personnel of Women’s hospital at Jorvi, Kätilöopisto and Naistenklinikka for their flexibility and support in the recruitment. We acknowledge Wellworks Ltd for the development and maintenance of the interactive HELMi questionnaire system and database. We are truly grateful for the participating families for their efforts and remarkable commitment, enabling this study.

Footnotes

ED and EH contributed equally.

Contributors: WdV, AS, K-LK and KK designed and established the cohort. AS and KK designed the online questionnaires and their interactive features. K-LK participated in the design of the questionnaires and acts as a responsible study doctor. AS and ED are responsible for the continued management of the cohort and KK for the data management. ED collects and archives the samples and EH and AS are responsible for project’s social media for recruitment, communication and dissemination purposes. ED, EH, AS and KK analysed the results and AS, EH and KL-K interpreted them. EH, AS and ED drafted and edited the manuscript. WMdV and K-LK revised major contents. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The establishment of the HELMi cohort and the required infrastructure for data collection was conducted with the support of Tekes, the Finnish Funding agency for Technology and Innovation (currently Business Finland), grant 329/31/2015 to WMdV and AS, under the medical supervision of KLK. The grant involves cofunding from three companies: Valio Ltd, Dupont Nutrition and Health and Oriola, and in-kind support from the with the Finnish Red Cross Blood service in FUT2 genotyping. The daily sampling within HELMiPlus subproject has been supported by the Academy of Finland grant 1297765 to KK. Academy of Finland grant 1308255 to WMdV supports the analysis of dust microbiota and integration of the data with all of the major Finnish population based birth cohorts. Academy of Finland grant 325103 to AS supports the organization of 4-year follow-up of the cohort. Personal grant by Paulo Foundation, and project grants by Päivikki ja Sakari Sohlberg Foundation and Biocodex Microbiota Foundation have been granted to AS. AS has received H2020-MSCA-ITN-2018 grant 8144102 and the Foundation for Nutrition Research grant to support two PhD projects. Specific microbiota analysis has been and will be supported by the unrestricted Spinoza award of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research to WMdV.

Competing interests: All authors declare support from Valio Ltd, Finnish Red Cross Blood Service, Dupont Nutrition and Health and Oriola Ltd in the form of a grant that has partially funded the study.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the ethical committee of The Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa (263/13/03/03 2015) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All microbiota data will me made publicly available upon publication of the results in scientific articles. Due to legislative and ethical reasons, questionnaire and registry data cannot be made freely accessible even in de-identified form without an application process that includes submission of a research plan that will first undergo evaluation by the HELMi scientific board and then by relevant research ethics committees.

Collaborators: We currently collaborate with Professor Katri Räikkönen and Adjunct professor Kati Heinonen (psychology; cognitive and developmental testing) from the University of Helsinki, Professor Marco Ventura (bifidobacterial analysis, bacterial genomics) from the University of Parma, Italy and Maijaliisa Erkkola from the University of Helsinki (nutritional sciences; dietary intake and nutritional assessment). Dr Pirkka Kirjavainen from the Environmental Health Unit, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Kuopio, Finland, will be responsible for coordinating the house dust analysis. Researchers interested in collaboration are invited to propose human genetics, immunological or epidemiological research based on the data available from the HELMi cohort or submit a suggestion for additional data collection. Requests should be sent to AS (anne.salonen@helsinki.fi) and will be reviewed by the HELMi scientific board.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Katri Räikkönen, Kati Heinonen, Maijaliisa Erkkola, Marco Ventura, and Pirkka Kirjavainen

References

- 1. Renz H, Brandtzaeg P, Hornef M. The impact of perinatal immune development on mucosal homeostasis and chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2011;12:9–23. 10.1038/nri3112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nylund L, Satokari R, Salminen S, et al. Intestinal microbiota during early life - impact on health and disease. Proc Nutr Soc 2014;73:457–69. 10.1017/S0029665114000627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stiemsma LT, Michels KB. The role of the microbiome in the developmental origins of health and disease. Pediatrics 2018;141:e20172437 10.1542/peds.2017-2437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tanaka M, Nakayama J. Development of the gut microbiota in infancy and its impact on health in later life. Allergol Int 2017;66:515–22. 10.1016/j.alit.2017.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Olin A, Henckel E, Chen Y, et al. Stereotypic Immune System Development in Newborn Children. Cell 2018;174:1277–92. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cox LM, Yamanishi S, Sohn J, et al. Altering the intestinal microbiota during a critical developmental window has lasting metabolic consequences. Cell 2014;158:705–21. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Francino MP. Early development of the gut microbiota and immune health. Pathogens 2014;3:769–90. 10.3390/pathogens3030769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hill CJ, Lynch DB, Murphy K, et al. Evolution of gut microbiota composition from birth to 24 weeks in the INFANTMET Cohort. Microbiome 2017;5:4 10.1186/s40168-016-0213-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Scheepers LE, Penders J, Mbakwa CA, et al. The intestinal microbiota composition and weight development in children: the KOALA Birth Cohort Study. Int J Obes 2015;39:16–25. 10.1038/ijo.2014.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Subbarao P, Anand SS, Becker AB, et al. The Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) Study: examining developmental origins of allergy and asthma. Thorax 2015;70:998–1000. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stewart CJ, Ajami NJ, O’Brien JL, et al. Temporal development of the gut microbiome in early childhood from the TEDDY study. Nature 2018;562:583–588. 10.1038/s41586-018-0617-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bisgaard H. The Copenhagen Prospective Study on Asthma in Childhood (COPSAC): design, rationale, and baseline data from a longitudinal birth cohort study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2004;93:381–9. 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61398-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yang HJ, Lee SY, Suh DI, et al. The Cohort for Childhood Origin of Asthma and allergic diseases (COCOA) study: design, rationale and methods. BMC Pulm Med 2014;14:109 10.1186/1471-2466-14-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wacklin P, Mäkivuokko H, Alakulppi N, et al. Secretor genotype (FUT2 gene) is strongly associated with the composition of Bifidobacteria in the human intestine. PLoS One 2011;6:e20113 10.1371/journal.pone.0020113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Korpela K, Salonen A, Virta LJ, et al. Intestinal microbiome is related to lifetime antibiotic use in Finnish pre-school children. Nat Commun 2016;7:10410 10.1038/ncomms10410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Official Statistics of Finland (OSoF): Väestön koulutusrakenne. ISSN=1799-4586. 2016. Helsinki: Tilastokeskus [referred: 25.8.2018] http://www.stat.fi/til/vkour/

- 17. Haahtela T, von Hertzen L, Makela M, et al. Allergy Programme Working G. Finnish Allergy Programme2008-2018time to act and change the course. Allergy 2008;63:634–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jousilahti P, Haahtela T, Laatikainen T, et al. Asthma and respiratory allergy prevalence is still increasing among Finnish young adults. Eur Respir J 2016;47:985–7. 10.1183/13993003.01702-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. The Social Insurance Institution Kela: Statistics on reimbursements for prescription medicines. https://www.kela.fi/tilastot-aiheittain_tilasto-laakkeiden-korvausoikeuksista 2018. (Accessed 9 Mar 2018).

- 20. Virta LJ, Kaukinen K, Collin P. Incidence and prevalence of diagnosed coeliac disease in Finland: results of effective case finding in adults. Scand J Gastroenterol 2009;44:933–8. 10.1080/00365520903030795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Official Statistics of Finland (OSoF). Perinatal statistics - parturients, deliveries and newborns. Helsinki: National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) http://www.stat.fi/til/sysyvasy/index_en.html (Referred: 8 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease-revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR 2010;59:1–32. Available at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5910a1.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Erkkola M, Salmenhaara M, Kronberg-Kippilä C, et al. Determinants of breast-feeding in a Finnish birth cohort. Public Health Nutr 2010;13:504–13. 10.1017/S1368980009991777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) database: Breastfeeding rates. 2009. https://wwwoecdorg/els/family/43136964pdf (Accessed 24 Aug 2018).

- 25. Milani C, Lugli GA, Turroni F, et al. Evaluation of bifidobacterial community composition in the human gut by means of a targeted amplicon sequencing (ITS) protocol. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2014;90:n/a–503. 10.1111/1574-6941.12410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jayaprakash B, Adams RI, Kirjavainen P, et al. Indoor microbiota in severely moisture damaged homes and the impact of interventions. Microbiome 2017;5:138 10.1186/s40168-017-0356-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028500supp001.pdf (53.2KB, pdf)