Abstract

Objective

To examine predefined risk factors and outcome of seizures in community-acquired bacterial meningitis (CABM).

Design

Observational cohort studies

Setting

Denmark

Participants

In the derivation cohort, we retrospectively included all adults (>15 years of age) with CABM in North Denmark Region from 1998 to 2014 and at Hvidovre and Hillerød hospitals from 2003 to 2014. In the validation cohort, we prospectively included all adults (>18 years of age) with CABM treated at all departments of infectious diseases in Denmark from 2015 to 2017.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

In the derivation cohort, we used modified Poisson regression to compute adjusted relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals for predefined risk factors for seizures during CABM as well as for risks of death and unfavourable outcome assessed by the Glasgow Outcome Scale score (1-4). Next, results were validated in the validation cohort.

Results

In the derivation cohort (n=358), risk factors for seizures at any time were pneumococcal aetiology (RR 1.69, 1.01–2.83) and abnormal cranial imaging (RR 2.27, 1.46–3.53), while the impact of age >65 years and immunocompromise was more uncertain. Examining seizures occurring after admission, risk factors were abnormal cranial imaging (RR 2.23, 1.40–3.54) and immunocompromise (RR 1.59, 1.01–2.50). Seizures at any time were associated with increased risks of in-hospital mortality (RR 1.45, 1.01–2.09) and unfavourable outcome at discharge (RR 1.27, 1.02–1.60). In the validation cohort (n=379), pneumococcal aetiology (RR 1.69, 1.10–2.59) and abnormal cranial imaging (RR 1.68, 1.09–2.59) were confirmed as risk factors for seizures at any time. For seizures occurring after admission, only pneumococcal meningitis (RR 1.92, 1.12–3.29) remained significant. Seizures at any time were also associated with in-hospital mortality (RR 3.26, 1.83–5.80) and unfavourable outcome (RR 1.23, 1.00–1.52) in this cohort.

Conclusions

Pneumococcal aetiology, immunocompromise and abnormal cranial imaging were risk factors for seizures in CABM. Seizures were strongly associated with mortality and unfavourable outcome.

Keywords: epidemiology, epilepsy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Using a two-cohort design, we first analysed the data in a retrospective population-based derivation cohort and next validated the results in a contemporary prospective nationwide population-based observational cohort.

We defined risk factors and specified adjustments prior to data acquisition and analyses based on previous studies and biological reasoning.

We included clinically meaningful risk factors amenable for future improvement such as antibiotic delay and treatment with adjunctive dexamethasone.

Risk factors were also examined in stratified analyses of seizures occurring before or immediately at admission and seizures occurring during admission.

Limitations inherent of retrospective designs also applied to our study including unavailability of electroencephalographs, random missing values and non-standardised treatment.

Introduction

Community-acquired bacterial meningitis (CABM) is a devastating and often fatal condition. Seizures are frequent in CABM and have been associated with increased case fatality.1–5 The pathogenesis of seizures in CABM may involve inflammatory neuronal excitation, necrosis and increased intracranial pressure. A previous study compared patients with CABM complicated by seizures to those without seizures and found that they more often had cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leucocytes <1000/mL, CSF protein >3.0 g/L, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, a pneumococcal aetiology and focal cerebral abnormalities.1

Some authors advocate routine administration of anticonvulsive therapy in patients with suspected pneumococcal meningitis irrespective of whether or not seizures have occurred.2 This recommendation, however, has not been formally shown to improve the prognosis and is not adopted by most guidelines.6 7 So far, few studies have specifically addressed risk factors and prognosis of seizures in CABM and previous results should be validated in other cohorts. A better understanding of clinical characteristics associated with increased risk of seizures could help define a population of adult patients eligible for a clinical trial of anticonvulsive therapy in CABM.

Therefore, we aimed to examine predefined risk factors for seizures in adult patients with CABM and the prognostic effect of seizures on outcome in a retrospective cohort. Next, we validated our results in a nationwide prospective bacterial meningitis cohort.

Material and methods

Setting and study population

In Denmark, healthcare is financed by taxes and therefore free of charge at the point of delivery. All residents are assigned a unique 10-digit personal identification number at birth or immigration, which can be used to access information from all hospitalisations and other healthcare-related contacts.

Derivation cohort

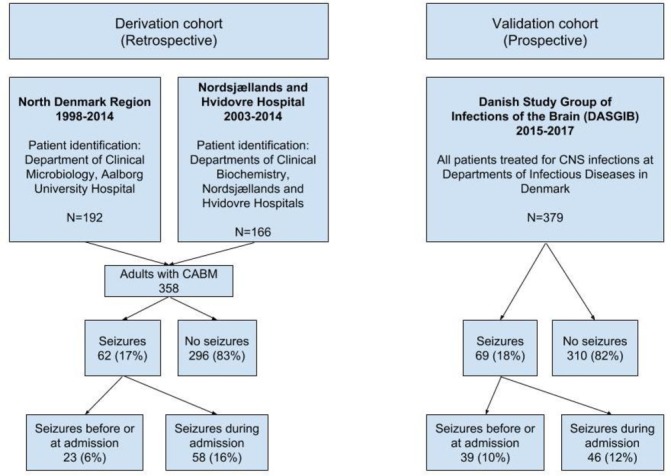

We combined two retrospective cohorts of adult patients with CABM from North Region Denmark (1998–2014) and Nordsjællands and Hvidovre Hospitals (2003–2014) as described previously (figure 1).8 We used the electronic laboratory information systems to identify patients (ADBakt, Autonik Sweden at the Department of Clinical Microbiology at Aalborg University Hospital and LABKA II, CSC Scandihealth, Denmark, at the Departments of Clinical Biochemistry at Hvidovre and Nordsjællands Hospitals). We included all patients >15 years of age with a clinical presentation suggesting CABM and at least one of the following criteria8:

Figure 1.

Flowchart of included patients with CABM in the derivation and validation cohorts. CABM, community-acquired bacterial meningitis; CNS, central nervous system.

Positive CSF culture.

Positive blood culture and CSF pleocytosis >10 leucocytes/mL.

Presence of bacteria on Gram stain of CSF.

Non-culture detection of bacteria in CSF by PCR-based technology or antigen analyses.

Exclusion criteria were previous neurosurgery, primary brain abscesses or hospital-acquired bacterial meningitis as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.9

Patient data

We used the medical records to examine baseline characteristics including patient history, symptoms and signs at admission, time of diagnosis (at admission or later), adjuvant dexamethasone treatment and laboratory results (biochemistry, radiology, microbiology). For radiological results, we relied on the radiologist’s descriptions. We defined immunocompromise as presence of any of the following comorbidities: alcohol abuse, asplenia, diabetes mellitus, renal impairment, liver cirrhosis, immunosuppressive therapy (eg, chemotherapy or high-dose prednisolone), solid or haematological cancer. Observation charts were obtained for patients who were treated in an intensive care unit (ICU). For patients with seizures, we included prior history of seizure disorder, use of anticonvulsive therapy as well as type, day(s) and cumulative incidence of seizures during admission for CABM. Electroencephalographs (EEGs) were not available in the medical records. We used the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score at discharge for assessment of outcome and categorised a GOS score of 5 as favourable, while GOS 1–4 were considered an unfavourable outcome.

Validation cohort

We used the Danish Study Group of Infections of the Brain (DASGIB) bacterial meningitis cohort to validate our results.10 Briefly, all adults with central nervous system infections treated by departments of infectious diseases in Denmark have been prospectively included in a database since 1 January 2015. The database contains information on baseline demographics, signs and symptoms at admission, time to antibiotic therapy for CABM, laboratory and imaging results, complications during admission and GOS scores at discharge. As in the derivation cohort, episodes of seizures analysed in this study were restricted to those occurring before or at some point during admission or stay at rehabilitation unit until discharge to home or nursing home. We validated our findings among patients with CABM registered in the DASGIB cohort from year 2015 through 2017. Prior to carrying out the current study, the DASGIB cohort was first registered on www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03418441) on February 1, 2018.

Statistical analyses

Baseline data are presented in contingency tables. Categorical variables are presented as proportions with percentages (%) and examined by Fisher’s exact test or Χ2, while continuous variables are presented as medians with IQR and compared by Mann-Whitney U-test.

Using modified Poisson regression analyses, we computed adjusted relative risks (RRs) with 95% CIs for seizures at any time and for new onset seizures after admission only.11 Based on previous studies and biological plausibility, our prespecified variables consisted of: Age >65 years, immunocompromise, pneumococcal aetiology, time to antibiotic therapy for CABM within 2 hours of admission, adjunctive dexamethasone treatment and abnormal cranial imaging.1 Examining risk factors for new onset seizures after admission in the validation cohort, a limited number of events (n=44) restricted the analysis to four prioritised variables: Age >65 years, immunocompromise, pneumococcal aetiology and abnormal cranial imaging.

Next, we used similar multivariable analyses to compute the prognostic value of seizures at any time during CABM on risk of death and unfavourable outcome at discharge. These analyses of outcome were adjusted for age >65 years, sex, diagnosis of meningitis immediately at admission, time to antibiotic therapy for CABM within 2 hours of admission, pneumococcal aetiology, adjuvant dexamethasone treatment and GCS <15 at admission. However, time of diagnosis was not available in the DASGIB database and was therefore omitted from the adjusted outcome analyses in this cohort. We also performed a sensitivity analysis of risk factors and outcome excluding the five patients with known seizure disorder.

We used STATA MP V.15.1 for all statistical analyses.

Ethics

The study was notified to the Danish Data Protection Agency in North Denmark Region (record no. 2008-58-0028) and Capital Region of Denmark (record no. 01 706 hvh-2012–016, NOH-2015–012) and the Danish Health and Medicines Authority (record no. 3-3013-135/1 and 3-3013-2579/1). An approval from an ethics committee is not required for this type of study in Denmark.

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor public institutions were involved in this study. There are no plans of disseminating the results of this report to study participants besides publication in an open-access medical journal.

Results

Derivation cohort

Seizures at any time during CABM occurred in 62 of 358 (17%) patients in the derivation cohort of whom 23 (6%) had seizures before or immediately at the time of admission (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with community-acquired bacterial meningitis with and without seizures at any time during admission

| Baseline characteristics | Seizures (n=62) |

No seizures (n=296) | P value |

| Age (IQR), n=358 | 63 (51–70) | 58.5 (46–70) | 0.13 |

| Female | 27/62 (44) | 152/296 (51) | 0.26 |

| Immunocompromise, n=358 | 28/62 (45) | 95/296 (32) | 0.049 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7/62 (11) | 17/296 (6) | 0.11 |

| Alcohol abuse | 11/62 (18) | 39/296 (13) | 0.35 |

| Otitis/sinusitis/mastoiditis/pneumonia | 31/62 (50) | 107/296 (36) | 0.04 |

| Duration of symptoms (days), n=183 | 2 (2–3.5) | 2 (2–5) | 0.42 |

| Symptoms and signs on presentation | |||

| Headache | 36/49 (73) | 175/234 (75) | 0.85 |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 21/45 (47) | 93/201 (46) | 0.96 |

| Neck stiffness | 38/58 (66) | 180/273 (66) | 0.95 |

| Temperature (°C), n=327 | 38.8 (37.8–39.7) | 39.0 (37.9–39.7) | 0.73 |

| Petechiae | 10/48 (21) | 49/216 (23) | 0.78 |

| Focal neurological deficits | 13/62 (21) | 31/294 (11) | 0.02 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale <15, n=358 | 53 (85) | 213 (72) | 0.03 |

| Diagnosed before or at admission, n=358 | 37 (60) | 208 (70) | 0.10 |

| Time to antibiotic therapy for meningitis since admission (hours), n=333 | 2.8 (1.0–12) | 2.45 (1–8) | 0.57 |

| Laboratory results | |||

| C-reactive protein (mg/L), n=358 | 204 (108–327) | 215 (115–303) | 0.74 |

| B-leucocytes (109/L), n=332 | 17 (10–25) | 17 (12–23) | 0.67 |

| B-thrombocytes (109/L), n=307 | 197 (130–268) | 199 (131–272) | 0.77 |

| S-creatinine (µmol/L), n=318 | 92 (66–138) | 81 (64–107) | 0.19 |

| CSF leucocytes (median, IQR) (106/L), n=346 | 2806 (287–6845) | 2110 (483–5520) | 0.82 |

| Protein in CSF (g/L), n=323 | 4.3 (2.1–9.1) | 3.6 (1.8–6.5) | 0.09 |

| CSF:blood glucose ratio (mmol/L), n=323 | 1.2 (0.1–2.8) | 1.1 (0.1–3.0) | 0.96 |

| Positive blood culture, n=358 | 41 (66) | 167 (56) | 0.29 |

| Positive CSF culture, n=358 | 51 (82) | 247 (83) | 0.34 |

| Pneumococcal aetiology, n=358 | 43 (69) | 151 (51) | 0.008 |

| Meningococcal aetiology, n=358 | 3 (5) | 56 (19) | 0.007 |

| Adjunctive dexamethasone treatment, n=358 | 33 (53) | 148 (50) | 0.66 |

| Intensive care unit treatment, n=358 | 57 (92) | 149 (51) | <0.001 |

Data presented as n/N (%) or medians (IQR).

Immunocompromise: alcohol abuse, asplenia, diabetes mellitus, renal impairment, liver cirrhosis, immunosuppressive therapy (eg, chemotherapy or high-dose prednisolone), solid or haematological cancer.

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Five (9%) of these patients had a known seizure disorder before CABM. For 15 patients, the day and type of seizures in CABM were not specified in the medical records. The median time of first seizure episode in patients only having seizures during admission was day 1 (IQR 1–2). Types of seizures observed were generalised in 34 patients, focal in 10 of which 4 had secondary generalisation and non-convulsive status epilepticus in 3. The median number of days with seizures was 1 (IQR 1–2, range 1–23). Treatment for seizures was administered to 43 of 62 (69%) patients of whom 30 (48%) were given combination anticonvulsive therapy (9 patients if combinations with benzodiazepines were not included). Anticonvulsive treatments used included benzodiazepines in 30 (48%) patients, sedation in the ICU in 17 (27%), valproate in 11 (18%), phenytoin in 5 (8%), lamotrigine in 2 (3%), levetiracetam in 2 (3%), oxcarbazepine and carbamazepine in 1 each (2%).

Comparing patients with seizures at any time during CABM to patients without seizures, we observed no substantial differences in most presenting symptoms or baseline blood and CSF biochemistry (table 1). However, focal neurological deficits (13 of 62 (21%) vs 31 of 296 (11%)) and altered mental status (53 of 62 (85%) vs 213 of 296 (72%)) were more common in these patients than in patients without seizures. Seizures occurred in 43 of 194 (22%) patients with pneumococcal meningitis compared with 19 of 145 (13%) patients with other aetiologies (table 2).

Table 2.

Causative pathogens of community-acquired bacterial meningitis in patients with and without seizures at any time during admission

| Bacterial aetiology | Seizures (n=62) | No seizures (n=296) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 43 (69) | 151 (51)* |

| Neisseria meningitidis | 3 (5) | 56 (19)* |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 4 (6) | 22 (7) |

| Beta-haemolytic streptococci (A, B, C, G) | 4 (6) | 10 (3) |

| Non-haemolytic streptococci | 2 (3) | 6 (2) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 (2) | 20 (7) |

| Escherichia coli | - | 8 (3) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 3 (5) | 13 (4) |

| Capnocytophaga canimorsus | - | 5 (2) |

| Klebsiella pneumonia | - | 1 (1) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 1 (2) | 3 (1) |

| Pasteurella multocida | 1 (2) | - |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | - | 1 (1) |

Data are presented as n (%).

*P value <0.05.

Conversely, seizures were only observed among 3 of 59 (5%) patients with meningococcal meningitis. Abnormalities in cranial imaging were found in 28 of 57 (48%) patients with seizures compared with 62 of 209 (30%) patients without seizures with infarction as the most common finding (table 3).

Table 3.

Cranial imaging in patients with community-acquired bacterial meningitis with or without seizures at any time during admission

| Baseline characteristics | Seizures (n=57) |

No seizures (n=209) | P value |

| Abnormal cranial imaging | 28 (49) | 62 (30) | 0.006 |

| Infarction | 15 (26) | 23 (11) | 0.003 |

| Generalised brain swelling | 7 (12) | 15 (7) | 0.22 |

| Haemorrhage | 4 (7) | 14 (7) | 0.93 |

| Hydrocephalus | 0 | 10 (5) | 0.09 |

| Ventriculitis | 1 (2) | 5 (2) | 0.77 |

| Cerebritis | 1 (2) | 4 (2) | 0.94 |

| Malignant tumour | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | 0.61 |

| Secondary brain abscess/empyema | 2 (4) | 1 (1) | 0.06 |

| Sinus thrombosis | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.32 |

Data are presented as n (%).

Twenty-two of 62 (35%) patients with seizures died during admission for CABM versus 62 of 296 (21%) in patients without seizures, while unfavourable outcome at discharge occurred in 39 of 62 (63%) versus 127 of 296 (43%) patients (table 4). There was no difference in fatal outcome among patients with seizures who received anti-epileptic treatment and those who did not (17 of 43 (40%) versus 5 of 19 (26%) patients, p=0.32).

Table 4.

Outcomes of patients with community-acquired bacterial meningitis with or without seizures at any time during admission

| Outcome | Seizures (n=62) | No seizures (n=296) |

| Glasgow Outcome Scale score | ||

| 1 | 22 (35) | 62 (21)* |

| 2 | - | 2 (1) |

| 3 | 7 (11) | 28 (9) |

| 4 | 10 (16) | 35 (12) |

| 5 | 23 (37) | 169 (57)* |

| Seizures after discharge/subsequent epilepsy | 7/62 (13) | Na |

| Duration of admission (days), n=358 | 21 (12–36) | 14 (10–23)* |

| Time to death (days), n=358 | 7 (3–27) | 8 (3–16) |

Data are presented as n (%) or medians (IQR).

*P value <0.05.

Na, not available.

Examining risk factors for seizures at any time during admission by univariable and multivariable analyses, we observed an increased risk in patients with pneumococcal aetiology (adjusted RR 1.69, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.83) and abnormal cranial imaging (adjusted RR 2.27, 95% CI 1.46 to 3.53) compared with patients without these characteristics (tables 5 and 6).

Table 5.

Univariate analysis for risk factors of seizures in CABM using patients with no seizures as reference

| Risk factor for seizures during CABM | Retrospective cohort (n=358) | Prospective cohort (n=379) |

| Seizures at any time during infection | n=62 (17%) | n=69 (18%) |

| Age >65 years | 1.46 (0.93 to 2.29) | 1.54 (0.99 to 2.41) |

| Immunocompromise | 1.57 (1.00 to 2.47) | 1.56 (1.02 to 2.40) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.77 (0.91 to 3.46) | 2.21 (1.35 to 3.64) |

| Alcohol abuse | 1.33 (0.74 to 2.37) | 1.27 (0.64 to 2.53) |

| Abnormal cranial imaging | 2.45 (1.58 to 3.81) | 1.76 (1.15 to 2.69) |

| Pneumococcal aetiology | 1.91 (1.16 to 3.15) | 1.58 (1.03 to 2.41) |

| Diagnosed immediately at admission | 0.68 (0.43 to 1.08) | - |

| Antibiotics for meningitis within 2 hours | 0.98 (0.62 to 1.55) | 0.84 (0.53 to 1.33) |

| Adjunctive dexamethasone treatment | 1.11 (0.71 to 1.75) | 0.83 (0.53 to 1.28) |

| Glasgow Coma Scale at admission <15 | 2.04 (1.05 to 3.97) | 2.12 (1.29 to 3.48) |

| C-reactive protein >100 mg/L | 0.86 (0.50 to 1.48) | 0.71 (0.45 to 1.12) |

| CSF leucocytes <1000/mL | 0.94 (0.58 to 1.52) | 0.98 (0.64 to 1.51) |

| CSF protein >3.0 g/L | 1.29 (0.29 to 2.10) | 1.81 (1.17 to 2.82) |

| Seizures during admission | n=58 (16%) | n=46 (12%) |

| Age >65 years | 1.53 (0.96 to 2.45) | 1.64 (0.93 to 2.91) |

| Seizures before or immediately at admission | 6.44 (4.41 to 9.40) | 5.01 (1.84 to 13.7) |

| Immunocompromise | 1.78 (1.12 to 2.85) | 1.39 (0.80 to 2.41) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.91 (0.97 to 3.75) | 2.32 (1.22 to 4.41) |

| Alcohol abuse | 1.44 (0.80 to 2.59) | 1.07 (0.41 to 2.79) |

| Abnormal cranial imaging | 2.42 (1.53 to 3.83) | 1.66 (0.96 to 2.87) |

| Pneumococcal aetiology | 1.88 (1.12 to 3.15) | 1.88 (1.09 to 3.24) |

| Diagnosed immediately at admission | 0.61 (0.38 to 0.97) | - |

| Antibiotics for meningitis within 2 hours | 0.96 (0.59 to 1.55) | 0.78 (0.43 to 1.41) |

| Adjunctive dexamethasone treatment | 1.29 (0.80 to 2.08) | 0.67 (0.39 to 1.15) |

| Glasgow Coma Scale at admission <15 | 1.48 (0.80 to 2.73) | 1.71 (0.94 to 3.09) |

| C-reactive protein >100 mg/L | 1.37 (0.71 to 2.66) | 0.71 (0.40 to 1.27) |

| CSF leucocytes <1000/mL | 1.21 (0.75 to 1.96) | 1.14 (0.66 to 1.96) |

| CSF protein >3.0 g/L | 1.48 (0.87 to 2.50) | 2.19 (1.23 to 3.88) |

Data are presented as relative risks with 95% CI.

CABM, community-acquired bacterial meningitis; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Table 6.

Multivariate analyses for risk factors of seizures in CABM using patients with no seizures as reference

| Risk factor for seizures during CABM | Derivation cohort (n=358) | Validation cohort (n=379) |

| Seizures at any time during infection | n=62 (17%) | n=69 (18%) |

| Age >65 years | 1.40 (0.90 to 2.18) | 1.43 (0.90 to 2.29) |

| Immunocompromise | 1.42 (0.92 to 2.19) | 1.44 (0.93 to 2.23) |

| Pneumococcal aetiology | 1.69 (1.01 to 2.83) | 1.69 (1.10 to 2.59) |

| Abnormal cranial imaging | 2.27 (1.46 to 3.53) | 1.68 (1.09 to 2.59) |

| Antibiotic therapy for meningitis within 2 hours of admission | 0.98 (0.63 to 1.54) | 0.94 (0.57 to 1.54) |

| Adjunctive dexamethasone treatment | 1.05 (0.68 to 1.63) | 0.83 (0.51 to 1.34) |

| Seizures during admission | n=58 (16%) | N=46* (12%) |

| Age >65 years | 1.48 (0.93 to 2.35) | 1.60 (0.90 to 2.85) |

| Immunocompromise | 1.59 (1.01 to 2.50) | 1.30 (0.76 to 2.25) |

| Pneumococcal aetiology | 1.62 (0.96 to 2.73) | 1.92 (1.12 to 3.29) |

| Abnormal cranial imaging | 2.23 (1.40 to 3.54) | 1.59 (0.92 to 2.77) |

| Antibiotic therapy for meningitis within 2 hours of admission | 0.96 (0.60 to 1.53) | - |

| Adjunctive dexamethasone treatment | 1.23 (0.77 to 1.95) | - |

Data are presented as relative risks with 95% CI.

*The limited number of events in this group restricted the number of variables included in the adjusted model as described under ‘Statistical analyses’.

CABM, community-acquired bacterial meningitis.

Restricting the multivariable analysis to patients with seizures during admission, only abnormal cranial imaging (adj. RR 1.90, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.98) and immunocompromise (adj. RR 1.62, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.57) were significantly associated with increased risk, while pneumococcal aetiology also suggested an association (adj. RR 1.65, 95% CI 0.99 to 2.76). Significant associations between seizures and abnormal cranial imaging were confirmed in stratified analyses of pneumococcal aetiology (data not shown).

Seizures at any time during CABM increased the risk of case fatality by 45% (adj. RR 1.45, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.09) and the risk of unfavourable outcome at discharge by 27% (adj. RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.60). Stratified analyses of pneumococcal meningitis patients with seizures at any time during admission compared with those without seizures showed an increased case fatality (14 of 43 (33%) vs 31 of 151 (21%), p=0.10) and risk of unfavourable outcome at discharge (28 of 43 (65%) vs 70 of 151 (46%), p=0.03).

Validation cohort

Next, we validated our results among 379 adult patients (47% female) with CABM in the DASGIB cohort. The median age was 66 years (IQR 54–74) and seizures at any time during admission occurred in 69 of 379 (18%) patients. The aetiology was predominated by Streptococcus pneumoniae (41%) followed by Staphylococcus aureus (10%) and beta-haemolytic streptococci (5%). A fatal outcome was observed in 50 of 379 (13%) patients, while an unfavourable outcome at discharge was found in 199 of 379 patients (53%) in this cohort.

We confirmed that pneumococcal aetiology (adj. RR 1.69, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.59) and abnormal cranial imaging (adj. RR 1.68, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.59) were associated with increased risks of seizures at any time during admission (table 6). When we restricted the analysis to seizures after admission, only pneumococcal aetiology remained associated with increased risks (adj. RR 1.92, 95% CI 1.12 to 3.29). Seizures at any time during CABM increased the risk for case fatality by 226% (adj. RR 3.26, 95% CI 1.83 to 5.80) and for unfavourable outcome at discharge by 23% (adj. RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.52).

Supplementary analyses in both the derivation and validation cohorts revealed no substantial effects of time to antibiotic therapy for CABM within 2 hours of admission or adjunctive dexamethasone on risks of seizures in CABM (tables 5 and 6).

Sensitivity analyses excluding patients with known seizure disorder (n=5) did not change the overall results of risk factors or prognosis in either cohort.

Discussion

We examined the association between several predefined variables and risk of seizures in adult CABM in two separate observational cohorts and identified pneumococcal meningitis, immunocompromise and abnormal cranial imaging (cerebral infarctions) as important risk factors. In addition, seizures were strongly associated with mortality and unfavourable outcome at discharge.

Comparisons with other studies

Few previous studies have specifically addressed risk factors for seizures in bacterial meningitis.1–5 A prospective Dutch observational study examined 696 episodes of CABM from 1998 through 2002 and found that 121 (17%) of patients had seizures at some point during infection,1 which is identical to the findings in our study. They also observed several differences between patients with and without seizures by univariate analyses, for example, in CSF biochemistry. However, in multivariable analyses, only immunocompromise and pneumococcal meningitis remained strongly associated with seizures at any time with the addition of focal cerebral abnormalities (defined as aphasia, monoparesis, hemiparesis or quadriparesis) for seizures after 48 hours of admission. The focal cerebral abnormalities may be correlates of brain infarctions as suggested by the high prevalence among patients with seizures compared with patients without seizures (20% vs 11%). Therefore, we consider the overall results comparable to ours with small differences in the methodology.

In our study, brain infarctions were found in 26% of CABM patients with seizures and 11% of those without seizures. In comparison, the incidence of seizures within 2 weeks among patients admitted with stroke typically ranges from 2% to 6.5%.12 Of relevance for the pathogenesis of brain infarction in CABM, a previous autopsy study of patients with pneumococcal meningitis documented extensive infarction and thrombosis in such patients and the authors hypothesised that infectious cerebral vasculitis or inflammation mediated by deposition of immune-complexes may be involved.13 This could potentially explain some of the observed associations between seizures, cerebral infarction and pneumococcal meningitis observed in our study. Further support may be derived by cerebral oedema or other intracranial complications being infrequent in patients with and without seizures in our study. Of note, studies remain inconclusive regarding the role of adjunctive dexamethasone in the rare occurrence of delayed-onset stroke after bacterial meningitis.14 15

Two other studies reported seizures more often among elderly (>65 and 60 years of age, respectively) than in younger CABM patients, but multivariable analyses of risk factors for seizures were not reported.2 16 Although the point estimates in our univariate and multivariate analyses consistently suggest age >65 years as a potential risk factor for seizures in CABM, the confidence intervals indicate too much statistical uncertainty for this to be a confirmed risk factor for now.

Similar to our study, other reports have examined seizures as a prognostic factor in bacterial meningitis and found increased risks of case fatality and unfavourable outcome.2 4 16–18 A prognostic model based on 176 patients with CABM from 1970 through 1995 showed an increased risk of in-hospital mortality or neurological deficits at discharge in patients with seizures at admission (OR 4.42, 95% CI 1.56 to 12.48).17 The model was adjusted for immune-competence, comorbidity and CSF leucocyte count and subsequently validated in a second cohort. Another study also observed an increased risk of in-hospital mortality in univariate analysis of bacterial meningitis patients with seizures within 24 hours of admission (RR 4.0, 95% CI 2.8 to 5.8).4 Likewise, a third study found seizures occurring after treatment initiation for CABM in elderly patients to be associated with in-hospital mortality (OR 6.8, 95% CI 1.7 to 27).2 The authors also state a protective effect of several variables including anti-seizure prophylaxis, but neither these results nor the statistical models were presented.

Finally, a large study of 352 patients with pneumococcal meningitis found an equal distribution of seizures at presentation among those with favourable outcome (8%) and unfavourable outcome (6%).19 This suggests that some of the observed prognostic effect of seizures on mortality and unfavourable outcome in our study could be related to seizures after admission or pneumococcal aetiology, even though we adjusted for the latter in our models.

Limitations

Several conditions could result in an underestimation of the cumulative incidence of seizures in CABM. These include patients admitted comatose without a detailed patient history, requests for cranial imaging before lumbar puncture with the risk of death before the diagnosis is confirmed (by lumbar puncture) or because a contraindication to lumbar puncture is present, for example, intracranial mass lesion. On the other hand, antibiotics used for CABM have been associated with a low absolute risk of seizures, which may lead to an increase in the incidence of seizures in these patients. However, we consider this negligible compared with the effect of severe inflammation of the meninges, high fever, brain infarctions and sepsis.

The categorisation of seizures into those occurring before or immediately at admission and those after admission is arbitrary, and may be influenced by, for example, time to diagnosis and disease severity. However, the distinction has clinical relevance, as seizures occurring after admission could be a target for prevention. Compared with patients without seizures, patients with seizures more often had cranial imaging performed in our study and were therefore more likely to be diagnosed with, for example, brain infarctions. Still, other abnormalities on cranial imaging did not differ suggesting a true difference in occurrence of clinically relevant infarctions between the two patient groups. Moreover, the occurrence of brain infarctions was similar in frequency to another study in which the cranial imaging was performed equally often among patients with and without seizures during CABM.1 A point of consideration is that MRI is more sensitive than CT in detecting brain infarctions but it was seldom used in our patients. This may have led to an underestimation in the incidence of intracranial abnormalities.

Other limitations inherent of observational studies also apply to our results. Some details concerning, for example, number and type of seizures as well as type of cranial imaging or distribution of infarctions were not always well described in the medical records. Further, reports of EEG were unavailable, which may underestimate the incidence of subclinical or non-convulsive status among patients with impaired consciousness Nonetheless, both frequency and seizure characteristics were comparable to a previous study with such information available.1 Missing values were accounted for by providing exact numbers of observations in the tables. Unfortunately, we only had sporadic information on intracranial pressures and were unable to perform meaningful analysis of associations with occurrence of seizures. Finally, the treatment of patients was performed by the responsible physician and may as such be subject to variation.

Implications

We agree with Zoons et al that a low threshold for anticonvulsant therapy in patients with seizures in CABM is prudent.1 Although the observed mortality with seizures in patients with CABM is high, causality cannot be inferred by observational studies and the associations could be due to, for example, pneumococcal aetiology, infarctions or disease severity. Therefore, routine anticonvulsive treatment to patients with CABM is not advised for now. Non-convulsive status was rare in our and other studies, but should be considered in patients with unexplained fluctuating consciousness or those who do not regain consciousness.1 Prolonged or intensified anti-inflammatory treatment could be considered in future experimental studies if infectious cerebral vasculitis is confirmed as an important contributor to infarctions, seizures and fatal outcome in a substantial part of patients with pneumococcal meningitis. Our observations were confirmed in a separate prospective cohort, and the characteristics associated with risk of seizures and adverse outcome could, together with findings in other studies, help define a patient population eligible for clinical trials of prophylactic anti-epileptic drugs in adults with CABM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all departments of infectious diseases in Denmark who participate in DASGIB.

Footnotes

Contributors: JB conceived the study. FTBDL, CTB, LL, VK, LW, JHL, BRH and JB participated in collection of data. FTBDL and JB analysed the data. FTBDL, CTB, LL, CØA, HN and JB interpreted the data. FTBDL wrote the first draft. CTB, LL, VK, LW, JHL, BRH, CØA, HN and JB critically reviewed the manuscript and all authors (FTBDL, CTB, LL, VK, LW, JHL, BRH, CØA, HN and JB) approved submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Permissions from the Danish Data Protection Agency and the Danish Board of Health are required before anonymised data can be shared by request from a qualified researcher.

Collaborators: Merete Storgaard (member of the DASGIB study group; e-mail merestor@rm.dk)

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published. Author name has been updated.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributor Information

On behalf of the DASGIB study group:

Collaborators: On behalf of the DASGIB study group

References

- 1. Zoons E, Weisfelt M, de Gans J, et al. Seizures in adults with bacterial meningitis. Neurology 2008;70:2109–15. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000288178.91614.5d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cabellos C, Verdaguer R, Olmo M, et al. Community-acquired bacterial meningitis in elderly patients. Medicine 2009;88:115–9. 10.1097/MD.0b013e31819d50ef [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van de Beek D, de Gans J, Spanjaard L, et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors in adults with bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1849–59. 10.1056/NEJMoa040845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Durand ML, Calderwood SB, Weber DJ, et al. Acute bacterial meningitis in adults. A review of 493 episodes. N Engl J Med 1993;328:21–8. 10.1056/NEJM199301073280104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kastenbauer S, Pfister HW. Pneumococcal meningitis in adults: spectrum of complications and prognostic factors in a series of 87 cases. Brain 2003;126:1015–25. 10.1093/brain/awg113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van de Beek D, Cabellos C, Dzupova O, et al. ESCMID guideline: diagnosis and treatment of acute bacterial meningitis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016;22 Suppl 3:1–26. 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McGill F, Heyderman RS, Michael BD, et al. The UK joint specialist societies guideline on the diagnosis and management of acute meningitis and meningococcal sepsis in immunocompetent adults. J Infect 2016;72:405–38. 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bodilsen J, Brandt CT, Sharew A, et al. Early versus late diagnosis in community-acquired bacterial meningitis: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018;24:166–70. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, et al. CDC definitions for nosocomial infections, 1988. Am J Infect Control 1988;16:128–40. 10.1016/0196-6553(88)90053-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bodilsen J, Storgaard M, Larsen L, et al. Infectious meningitis and encephalitis in adults in Denmark: a prospective nationwide observational cohort study (DASGIB). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018;24:1102.e1–5. 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702–6. 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Camilo O, Goldstein LB. Seizures and epilepsy after ischemic stroke. Stroke 2004;35:1769–75. 10.1161/01.STR.0000130989.17100.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Engelen-Lee J-Y, Brouwer MC, Aronica E, et al. Delayed cerebral thrombosis complicating pneumococcal meningitis: an autopsy study. Ann Intensive Care 2018;8:1–11. 10.1186/s13613-018-0368-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lucas MJ, Brouwer MC, van de Beek D. Delayed cerebral thrombosis in bacterial meningitis: a prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:866–71. 10.1007/s00134-012-2792-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schut ES, Brouwer MC, de Gans J, et al. Delayed cerebral thrombosis after initial good recovery from pneumococcal meningitis. Neurology 2009;73:1988–95. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c55d2e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weisfelt M, van de Beek D, Spanjaard L, et al. Community-acquired bacterial meningitis in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1500–7. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00878.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aronin SI, Peduzzi P, Quagliarello VJ. Community-acquired bacterial meningitis: risk stratification for adverse clinical outcome and effect of antibiotic timing. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:862–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-129-11_Part_1-199812010-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lai WA, Chen SF, Tsai NW, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of acute bacterial meningitis in elderly patients over 65: a hospital-based study. BMC Geriatr 2011;11:91 10.1186/1471-2318-11-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weisfelt M, van de Beek D, Spanjaard L, et al. Clinical features, complications, and outcome in adults with pneumococcal meningitis: a prospective case series. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:123–9. 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70288-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.