Abstract

Objectives

This article examines equity in enrolment in the Ghana National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) to inform policy decisions on progress towards realisation of universal health coverage (UHC).

Design

Secondary analysis of data from the sixth round of the Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS 6).

Setting

Household based.

Participants

A total of 16 774 household heads participated in the GLSS 6 which was conducted between 18 October 2012 and 17 October 2013.

Analysis

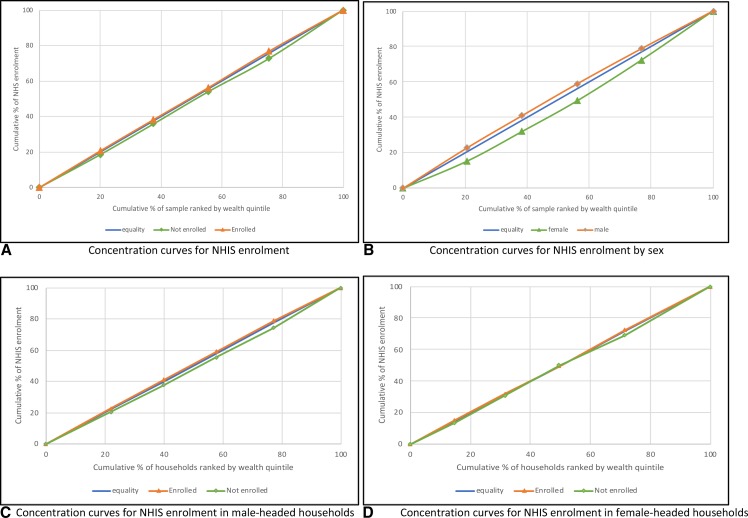

Equity in enrolment was assessed using concentration curves and bivariate and multivariate analyses to determine associated factors.

Main outcome measure

Equity in NHIS enrolment.

Results

Survey participants had a mean age of 46 years and mean household size of four persons. About 71% of households interviewed had at least one person enrolled in the NHIS. Households in the poorest wealth quintile (73%) had enrolled significantly (p<0.001) more than those in the richest quintile (67%). The concentration curves further showed that enrolment was slightly disproportionally concentrated among poor households, particularly those headed by males. However, multivariate logistic analyses showed that the likelihood of NHIS enrolment increased from poorer to richest quintile, low to high level of education and young adults to older adults. Other factors including sex, household size, household setting and geographic region were significantly associated with enrolment.

Conclusions

From 2012 to 2013, enrolment in the NHIS was higher among poor households, particularly male-headed households, although multivariate analyses demonstrated that the likelihood of NHIS enrolment increased from poorer to richest quintile and from low to high level of education. Policy-makers need to ensure equity within and across gender as they strive to achieve UHC.

Keywords: enrolment, equity, national health insurance scheme, Ghana

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study is the first to use data from the Ghana Living Standards Survey to examine equity in enrolment in the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS).

We developed concentration curves and multivariate logistic regression models to produce new findings to inform decision-making.

Unlike previous studies, this study found that enrolment in the NHIS is slightly concentrated among the poor; however, the odds of enrolling increases with wealth quintile, level of education and age.

As a secondary analysis, the data used for the study lack a number of important factors including trust in scheme management, perceived quality of care, ease of enrolment, etc., which would be useful for better understanding NHIS enrolment.

Introduction

Many low-income and middle-income countries are increasingly implementing prepayment schemes to provide financial risk protection and equitable access to healthcare services for their populations, particularly the poor.1–3 Prepayment schemes such as social health insurance, if implemented effectively, can reduce out-of-pocket payments (OOP) and associated catastrophic effects on households.4 The quest to ensure equity in access to healthcare services and to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) has become more imperative, following adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by member countries of the United Nations. Equity in prepayment schemes is also recognised by WHO as one of the fundamental elements of UHC.5

Ghana had a free healthcare system after independence in the 1950s, financed by general taxation. However, this system of healthcare changed when the economy started declining and user fees were partially introduced in the 1970s and 1980s to offset costs of healthcare services delivery.6–8 Although the OOP somewhat helped public healthcare services providers to recover partial costs of essential medicines and other pharmaceutical products and to raise revenue, the system-created inequity in access to healthcare and in some cases led to avoidable deaths.6 8 9 This situation resulted in the introduction of a National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in 2003 to replace OOP and ensure equity in healthcare access.10 The NHIS is managed by the National Health Insurance Authority, a body mandated by law to regulate both public and private health insurance schemes in the country.11

Membership in the NHIS is broadly categorised into exempt and non-exempt groups.11 The exempt groups are members who are exempted from paying premiums to the scheme and they include persons below 18 years of age, persons aged 70 years and above, pregnant women, indigent (extreme poor), formal sector workers who contribute to Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) and beneficiaries of the Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP) programme. The non-exempt group includes members who pay premiums and enrolment processing fees to the scheme and these are workers in the informal sector of the economy. The NHIS is tax-funded through the National Health Insurance Fund which is based on 2.5% levy on selected goods and services. Other sources of funding are a 2.5% deduction from formal sector workers’ SSNIT contributions, premiums from informal sector workers, funds allocated by parliament, interest from investments and donor funds and gifts.11 The premium and enrolment processing fee from the non-exempt group is GHS30.00 (US$6.33) per year. However, the exempt group only pays a processing fee of GHS8.00 (US$1.69) for new enrolment and GHS5.00 (US$1.05) for renewal of membership per year. Relative to the per capital income of GHS8863 (US$2035),12 the NHIS premium and processing fee represent 0.34%. Again, reference to the daily minimum wage of GHS10.65 (US$2.25)13 or GHS2769.00 (US$584.18) per year, the NHIS premium and processing fee constitute 0.38%.

Like many health systems around the globe, Ghana’s health system is hierarchical with the Ministry of Health (MoH) as apex body mandated to formulate policies to improve health of the population.14 The MoH has about 12 agencies, comprising the public, quasi-government and private health facilities, as well health education institutions. The biggest agency is the Ghana Health Service, which is charged with the responsibility of delivering healthcare to the population, as well as implementing policies of the MoH. The Ghana Health Service has a decentralised system of healthcare delivery with a considerable number of healthcare facilities located across the country. The lowest level of the healthcare delivery system is the community-based and health planning services compound and the highest being the tertiary or teaching hospitals at the national level. The number of healthcare facilities and professionals are unevenly distributed across the country, with the majority located in the urban areas.15 16 On the other hand, many of the private healthcare facilities particularly the faith-based ones are located in remote areas, where they provide about 40% of healthcare services to the population.14

Evidence shows that the NHIS has made progress in population coverage and contributed to utilisation of healthcare services and to expansion of healthcare facilities in its short period of existence.17 A report of the NHIS shows that the scheme has covered 36% (10.8 million) of the population as of December 2018.18 It has 166 district offices and a network of over 4000 healthcare providers comprising both public and private healthcare facilities across the country. The benefits package reportedly covers 95% of the disease conditions afflicting the population. It broadly covers outpatient services, inpatient services, oral health, eye care services, maternity care and emergencies.19 Preventive services, for example, immunisation and service that have the potential to pose sustainability challenges are excluded from the benefit package.9 11

There are few equity-oriented studies of the NHIS in Ghana. A mixed-method study that evaluated equity in NHIS enrolment in two regions (Central and Eastern) found that more males had registered in the scheme than females and households in the richest quintile were significantly more likely to enrol than those in the poorest quintile.1 The study also found that old age, higher education, female-headed households and perceived NHIS benefits were significantly associated with NHIS enrolment. Another mixed-method study examining why the NHIS is not reaching the poor used the same two regions and found fewer of the poor to be covered due to poverty and policy-makers’ and implementers’ lack of commitment to pursue NHIS’s equity goal.20 Kusi et al,21 in examining affordability of NHIS contribution, used three districts from the southern, middle and northern ecological zones of Ghana and also found that significantly more of the rich were enrolled in the NHIS than the poor. These three studies were conducted in 2008 and 2011 and employed bivariate and logistic regression analyses to examine enrolment equity. Other studies that also examined equity in NHIS enrolment, using data from the 2008 Ghana Demographic Health Survey, employed concentration curves and logistic regression and found that coverage was highest among the educated, households in the richest quintile, and urban residents.22 23

This study examines equity in enrolment in Ghana’s NHIS to inform policy decisions regarding attainment of UHC. It is necessary now to study equity to assess major NHIS policy reforms instituted in recent years to make the scheme more attractive to the general public. One such policy is the intersectoral collaboration with state-owned social protection institutions, for example, Ministry of Gender and Social Protection, Ministry of Education, LEAP Secretariat and Savannah Accelerated Development Authority, to increase the population of the poor and vulnerable in the NHIS and to improve equity. Findings from this study can inform policy-making on UHC attainment and contribute to the body of knowledge on equity in NHIS enrolment and progress towards achieving the SDGs.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study analyses secondary data from the sixth round of the Ghana Living Standards Survey conducted between 18 October 2012 and 17 October 2013. The survey covered a representative sample of 18 000 households in 1200 enumeration areas across the 10 administrative regions of the country.24 Survey participants had an average age of 44 years and 48 years for males and females, respectively. In the 2010 Population and Housing Census, Ghana had a population of 24 658 823, with 51.2% being females. The majority of the population resided in the Ashanti (19.4%) and Greater Accra (16.3%) regions, the two most urbanised regions25 of the country. These two regions also have the lowest poverty rates, while those in the northern savannah ecological zones (Northern, Upper East, Upper West, Brong-Ahafo, Volta) have the highest poverty rates.26 Online supplementary appendices 1 and 2 provide more details on the population distribution and poverty profile of Ghana.

Data collection and analysis

Data were sourced from the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) and had already been cleaned and managed including creation of sampling weights and wealth quintiles. The GSS constructed the wealth quintiles using household expenditure as a proxy.24 The household expenditure is composed of food and non-food items. The total number of households covered in the survey was divided into five groups by their total household consumption expenditure. The quintile ranking was then constructed using the household members total expenditure per capital. Bivariate analyses examined unadjusted relationships between socio-demographic factors and wealth quintiles. Equity in enrolment was assessed using concentration curves and indices, and multivariate logistic regression models to determine factors associated with enrolment.1 22 27 28 While the concertation curve analyses equity in NHIS enrolment between the poor and the rich, the logistic regression model shows factors associated with enrolment in the scheme. The use of these two analytical techniques is therefore meant to produce reliable findings for informed policy decision-making.

The unit of analysis was the household, and we examined cumulative proportion of enrolment by wealth quintiles, decomposed by sex, within and across male-headed and female-headed households. A multivariate logistic regression model was employed to assess whether lower wealth groups were more likely to enrol in the NHIS than higher wealth groups, holding the other socio-demographic variables constant. The outcome or dependent variable ‘NHIS enrolment status’ was labelled 1 for active card-bearing members and 0 for inactive card-bearing members or those who had never enrolled in the scheme. The main independent variable was ‘wealth quintile’ and the others (control variables) were socio-demographic characteristics such as age of household head, sex of household head, household size, education level of household head, household head employment status, household setting and geographic region of residence. Age of household head was categorised based on the Medical Subject Headings age definition.29 30 Microsoft Excel 2016 and STATA V.13 were used for all analyses.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in this study.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

A total of 16 772 household heads with an average age of 46 years (SD=15.58) and household size of 4 persons (SD=2.78) responded to questions on NHIS in the survey (table 1). Majority of the household heads (47%) were in the age bracket of 25–44 years. Out of the total number of survey participants, 72% were females; 51% had no formal education; 90% were employed; 24% were in the richest quintile; 56% lived in urban areas; and 12% resided in the Ashanti region. About 71% of households had at least one person enrolled in the NHIS.

Table 1.

Individual and household characteristics

| Variable | % (n=16 772) |

| NHIS status | |

| Covered | 70.5 |

| Not covered | 29.5 |

| Highest Education | |

| None | 50.7 |

| Primary | 30.5 |

| Secondary | 8.5 |

| Tertiary | 10.3 |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 89.5 |

| Unemployed | 10.5 |

| Wealth quintile | |

| Poorest | 20.1 |

| Poorer | 17.6 |

| Middle | 17.9 |

| Richer | 20.1 |

| Richest | 24.3 |

| Sex of household head | |

| Female | 71.8 |

| Male | 28.2 |

| Age of household head | |

| 19–24 | 4.9 |

| 25–44 | 47.1 |

| 45–64 | 33.3 |

| 65–79 | 11.7 |

| 80+ | 3 |

| Household size, M (SD) | 4.3 (2.78) |

| Household setting | |

| Rural | 44.4 |

| Urban | 55.6 |

| Geographic region | |

| Western | 10.2 |

| Central | 9.6 |

| Greater Accra | 11.5 |

| Volta | 9.4 |

| Eastern | 10.8 |

| Ashanti | 11.8 |

| Brong Ahafo | 9.7 |

| Northern | 10.2 |

| Upper East | 8.6 |

| Upper West | 8.3 |

M, mean; NHIS, National Health Insurance Scheme.

Equity in enrolment

Results of the concentration curve analyses demonstrate that enrolment was slightly more concentrated among poor households (figure 1). Enrolment by sex also showed that enrolment was more concentrated among households headed by males compared with those headed by females. The concentration indices further revealed that among the study participants, equity was more pronounced in the insured than the uninsured and within male-headed households than female-headed households (table 2).

Figure 1.

Concentration curves for enrolment in National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS).

Table 2.

Concentration index (CI) showing inequity in National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) enrolment

| Wealth quintile | Total | Within households (HH) | Between HH | |||||

| Enrolled | Not enrolled | Female-headed HH | Male-headed HH | Female | Male | |||

| Enrolled | Not enrolled | Enrolled | Not enrolled | |||||

| Poorest | −0.0009 | 0.0021 | −0.0023 | 0.0060 | −0.0009 | 0.0020 | 0.0073 | −0.0029 |

| Poorer | −0.0014 | 0.0035 | 0.0061 | −0.0153 | −0.0010 | 0.0026 | 0.0096 | −0.0039 |

| Middle | 0.0018 | −0.0039 | −0.0085 | 0.0234 | −0.0002 | 0.0011 | 0.0268 | −0.0108 |

| Richer | −0.0116 | 0.0290 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | −0.0135 | 0.0321 | 0.0455 | −0.0185 |

| Richest | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | −0.0056 | 0.0167 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Total | −0.0120 | 0.0307 | −0.0103 | 0.0307 | −0.0156 | 0.0378 | 0.0891 | −0.0362 |

Relationship between household characteristics and wealth quintiles

There were significant differences in all household characteristics by wealth quintiles, except employment status (table 3). The poorest households (73%) enrolled in the NHIS more than the richest households (67%). Interestingly, the richer households had the second highest enrolment (72.4%) in the scheme. Majority of the poorest households (80.1%) had no formal education compared with about 25% of the richest households with tertiary level education. Similarly, majority of the poorest households (91%) were more employed as were the richest households (89%), and there were more females (79%) in the poorest quintile than in the richest quintile (67%). There were also significantly more household heads aged 45 years or more in the poorest quintile than those in the richest quintile, and more households in the poorest quintile (86%) living in urban settings than households in the richest quintiles (30%).

Table 3.

Differences in household characteristics by wealth quintile (n=16 772)

| Variable | Q1 (poorest) | Q2 (poorer) | Q3 (middle) | Q4 (richer) | Q5 (richest) | Total | Pearson’s χ2 |

| NHIS status | 0.000 | ||||||

| Enrolled | 72.6 | 70.9 | 70.3 | 72.4 | 67.0 | 70.5 | |

| Not enrolled | 27.4 | 29.1 | 29.7 | 27.6 | 33.0 | 29.5 | |

| Highest education | 0.000 | ||||||

| None | 80.1 | 62.7 | 51.9 | 39.8 | 25.8 | 50.7 | |

| Primary | 16.3 | 28.7 | 34.8 | 38.7 | 33.6 | 30.5 | |

| Secondary | 2.1 | 5.4 | 7.0 | 10.1 | 15.8 | 8.5 | |

| Tertiary | 1.5 | 3.2 | 6.3 | 11.4 | 24.8 | 10.3 | |

| Employment status | 0.065 | ||||||

| Employed | 90.9 | 89.6 | 90.5 | 88.7 | 88.8 | 89.5 | |

| Unemployed | 9.1 | 10.4 | 9.5 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 10.5 | |

| Sex | 0.000 | ||||||

| Female | 79.1 | 73.1 | 71.7 | 69.4 | 66.9 | 71.8 | |

| Male | 20.9 | 26.9 | 28.3 | 30.6 | 33.1 | 28.2 | |

| Age of household head | 0.000 | ||||||

| 19–24 | 2.4 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 5.9 | 7 | 4.9 | |

| 25–44 | 40.9 | 43.8 | 46.6 | 48.4 | 54.1 | 47.1 | |

| 45–64 | 37.5 | 35 | 34.7 | 32 | 28.7 | 33.3 | |

| 65–79 | 14.9 | 14.2 | 11.4 | 10.9 | 7.9 | 11.7 | |

| 80+ | 4.3 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 3 | |

| Household size | 20.1 | 17.7 | 17.9 | 20.1 | 24.3 | 100 | 0.000 |

| Household setting | 0.000 | ||||||

| Rural | 13.7 | 31.1 | 43.6 | 56.0 | 70.4 | 44.4 | |

| Urban | 86.3 | 68.9 | 56.4 | 44.0 | 29.6 | 55.6 | |

| Geographic region | 0.000 | ||||||

| Western | 5.6 | 9.4 | 11.1 | 12.8 | 11.9 | 10.2 | |

| Central | 5.1 | 10.6 | 12.2 | 10.8 | 9.5 | 9.6 | |

| Greater Accra | 2.3 | 4.4 | 8.0 | 14.0 | 24.7 | 11.5 | |

| Volta | 8.7 | 11.0 | 9.8 | 10.1 | 7.9 | 9.4 | |

| Eastern | 7.0 | 11.8 | 13.8 | 13.1 | 8.9 | 10.8 | |

| Ashanti | 4.0 | 9.2 | 11.9 | 14.6 | 17.7 | 11.8 | |

| Brong-Ahafo | 8.4 | 11.9 | 11.0 | 9.6 | 8.2 | 9.7 | |

| Northern | 20.0 | 12.9 | 9.6 | 6.4 | 3.6 | 10.2 | |

| Upper East | 14.7 | 11.4 | 8.3 | 6.2 | 3.8 | 8.6 | |

| Upper West | 24.2 | 7.4 | 4.2 | 2.5 | 3.8 | 8.3 | |

NHIS, National Health Insurance Scheme.

Results of the multivariate logistic regression showed that the likelihood of enrolling in the NHIS increases from poorer to richest quintile, low to high level of education and young adults to older adults (table 4). Females (OR: 1.52; 95% CI: 1.39–1.65) and persons living in the Upper East (OR: 5.99; 95% CI: 4.91–7.31), Upper West (OR: 5.04; 95% CI: 4.14–6.15), Brong-Ahafo (OR: 3.06; 95% CI: 2.58–3.62), Volta (OR: 2.04; 95% CI:1.74–2.39) and Northern (OR: 1.32; 95% CI: 1.13–1.54) regions were significantly more likely to enrol in the NHIS than their respective reference categories. Surprisingly, the employed were less likely to enrol in the NHIS (OR=0.99; 95% CI 0.87–1.12) although not significantly so. The unadjusted odds ratios (OR) showed similar associations except for wealth quintile, the explanatory variable of interest, which showed a decreased likelihood of enrolling in the NHIS from poorer to richest.

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression model of enrolling in the National Health Insurance Scheme

| Variable | Unadjusted OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

| Wealth quintile | ||||

| Poorest | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Poorer | 0.92 | 0.82 to 1.02 | 1.33*** | 1.17 to 1.50 |

| Middle | 0.89* | 0.79 to 0.99 | 1.54*** | 1.36 to 1.75 |

| Richer | 0.98 | 0.88 to 1.09 | 1.94*** | 1.70 to 2.22 |

| Richest | 0.76*** | 0.69 to 0.84 | 1.67*** | 1.45 to 1.91 |

| Highest education | ||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Primary | 1.05 | 0.98 to 1.14 | 1.65*** | 1.51 to 1.80 |

| Secondary | 1.27*** | 1.12 to 1.44 | 2.35*** | 2.03 to 2.72 |

| Tertiary | 1.75*** | 1.55 to 1.99 | 2.87*** | 2.48 to 3.32 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Unemployed | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Employed | 0.85** | 0.76 to 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.87 to 1.12 |

| Sex of household head | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 1.11** | 1.03 to 1.19 | 1.52*** | 1.39 to 1.65 |

| Age of household head | ||||

| 19–24 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 25–44 | 1.99*** | 1.72 to 2.31 | 1.53*** | 1.31 to 1.79 |

| 45–64 | 2.38*** | 2.05 to 2.77 | 1.69*** | 1.43 to 1.99 |

| 65–79 | 3.43*** | 2.87 to 4.08 | 3.05*** | 2.51 to 3.69 |

| 80+ | 3.18*** | 2.47 to 4.08 | 3.28*** | 2.49 to 4.34 |

| Household size | 1.17*** | 1.15 to 1.18 | 1.23*** | 1.20 to 1.25 |

| Household setting | ||||

| Urban | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Rural | 0.97 | 0.91 to 1.04 | 0.75*** | 0.69 to 0.82 |

| Geographic region | ||||

| Western | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Central | 0.64*** | 0.55 to 0.73 | 0.63*** | 0.54 to 0.73 |

| Greater Accra | 0.79** | 0.69 to 0.90 | 0.63*** | 0.52 to 0.69 |

| Volta | 1.89*** | 1.62 to 2.21 | 2.04*** | 1.73 to 2.39 |

| Eastern | 1.34*** | 1.16 to 1.53 | 1.39*** | 1.20 to 1.62 |

| Ashanti | 1.16* | 1.01 to 1.32 | 1.08 | 0.94 to 1.25 |

| Brong-Ahafo | 2.68*** | 2.27 to 3.15 | 3.06*** | 2.58 to 3.62 |

| Northern | 1.07 | 0.92 to 1.22 | 1.32*** | 1.13 to 1.54 |

| Upper East | 4.30*** | 3.56 to 5.19 | 5.99*** | 4.91 to 7.31 |

| Upper West | 3.62*** | 3.01 to 4.33 | 5.04*** | 4.14 to 6.15 |

| _cons | 0.23*** | 0.18 to 0.29 | ||

| Number of obs. | 16 693 | |||

| LR chi2(24) | 2236.6 | |||

| Prob>chi2 | 0.0000 | |||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1106 |

Control variables: education of household head, employment status of household head, sex of household, age of household head, household size, household setting and geographic region.

***P<0.001; **P<0.01; *P<0.05.

Discussion

This study examined equity in NHIS enrolment employing data from the Ghana Living Standards Survey (round 6) which was conducted between October 2012 and October 2013. The findings show inequity in enrolment and significant associations between socio-demographic factors and NHIS enrolment. Among households surveyed, enrolment is disproportionally concentrated among poor households especially those headed by males. The possible explanation relates to policy changes made over the last few years to increase enrolment in the scheme. One such policy is the deliberate attempt to increase numbers of the poor and vulnerable in the scheme through enrolment of the LEAP beneficiaries, students in secondary and tertiary institutions in Ghana, prisoners and individuals living in less developed geographic regions, particularly those in the northern savannah ecological zone, where there is high prevalence of poverty. The disproportionate concentration of enrolment among poor households contradicts previous studies on the NHIS,1 20–22 31 32 due possibly to the years in which those studies were conducted (2008 and 2011), as well as the limited regional scope (three administrative regions except the 2008 Demographic Health Survey that covered the entire country). This present study employs a nationally representative survey.

Our study also shows that a number of socio-demographic factors are significantly associated with NHIS enrolment. Although unadjusted findings illustrate that enrolment is concentrated among poor households, multivariate findings illustrate that the odds of enrolling in the scheme increases with wealth quintiles, that is, the rich are more likely to enrol than the poor. This may be attributed to evidence that the rich are more able to afford the cost of enrolling in the health insurance programme than the poor.1 20 33 34 Besides, as explained earlier, the policy decision to deliberately enrol the poor might have contributed to their higher numbers in the NHIS, but voluntarily other factors other than being poor contribute to enrolment in the scheme. Individuals with higher levels of education are more likely to enrol in the NHIS compared with those with no formal education; females are more likely to enrol than males; and older adults are more likely to enrol than young adults, consistent with previous studies.1 22 32–35 The employed are less likely to enrol compared with the unemployed. The plausible explanation is that the employed may be able to afford OOP for healthcare services because they are more economically resourced than the unemployed. This result runs counter to earlier studies.21 35

Findings from this study also reveal that individuals residing in rural settings are significantly less likely to enrol in the NHIS compared with those living in urban areas, consistent with previous studies,32 35 but contradicting a study by Jehu-Appiah et al,1 One reason may be due to poverty; prior studies showed that the majority of rural dwellers are unable to afford the NHIS premium and processing or renewal fee.20 31 34 36–38 This study’s findings also show that the odds of enrolling in the NHIS increases with household size, consistent with other studies,22 33 34 because larger households may be risk averse and thus would enrol in the NHIS to seek financial risk protection against their healthcare costs and to avoid catastrophic OOP. Our findings also reveal that individuals residing in less developed regions of the country are significantly more likely to enrol in the scheme compared with those in developed regions. Again, this may be attributed to policy reforms focused on enrolling individuals living in deprived regions, particularly those in the northern savannah ecological zones, comprising the Northern, Upper East, Upper West and some parts of Brong-Ahafo and Volta regions,24 consistent with some studies22 23 and contradicting other.35

Our study’s primary limitation is that the data lacked several important factors (such as trust in scheme management, perceived quality of care, ease of enrolment, etc) which would be useful for better understanding NHIS enrolment. Nonetheless, the variables used in the multivariate logistic regression modelling did not significantly affect model robustness.

Conclusion

The study reveals that from 2012 to 2013, enrolment in the NHIS was higher among poor households, particularly male-headed households, although the multivariate analyses demonstrated that the likelihood of NHIS enrolment increased from poorer to richest quintile, low to high level of education and young adults to older adults. While the NHIS strives to achieve its pro-poor goal of providing financial risk protection for the poor and vulnerable in society, equity must be addressed within and across the entire population. Adequate funds are also required to cover the anticipated increase in medical claims costs because as more poor and vulnerable groups enrol in the scheme, the claims cost is likely to escalate and threaten the scheme’s sustainability. Thus, policy decisions to ensure equity in enrolment must also ensure commensurate funding to avoid financial uncertainty and collapse. Further research on equity in healthcare services utilisation, expenditures and accreditation of healthcare providers is needed to provide a fuller picture of equity assessment in the NHIS.

bmjopen-2019-029419supp001.pdf (208.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029419supp002.pdf (172.7KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Ghana Statistical Service for the provision of the GLSS data for this study. We also thank all contributors and reviewers for their comments and time.

Footnotes

Contributors: ENB, JPR and JN conceived and designed the study. JN retrieved the data and ENB analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. JPR and JN provided intellectual contributions to develop and revise the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the manuscript for publication.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: ENB is an employee of the National Health Insurance Authority, however his affiliation did not influence findings of this study. JPR and JN declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval: This study is a secondary analysis of the Ghana Living Standard Survey (round 6) data, however formal approval was obtained from the Ghana Statistical Service to use the data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data is available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Jehu-Appiah C, Aryeetey G, Spaan E, et al. . Equity aspects of the National Health Insurance Scheme in Ghana: Who is enrolling, who is not and why? Soc Sci Med 2011;72:157–65. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wiseman V, Thabrany H, Asante A, et al. . An evaluation of health systems equity in Indonesia: study protocol. Int J Equity Health 2018;17:1–9. 10.1186/s12939-018-0822-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Asante A, Price J, Hayen A, et al. . Equity in health care financing in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of evidence from studies using benefit and financing incidence analyses. PLoS One 2016;11:e0152866 10.1371/journal.pone.0152866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ruger JP. An alternative framework for analyzing financial protection in health. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001294 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Evans DB, Etienne C. Health systems financing and the path to universal coverage. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:402–128. 10.2471/BLT.10.078741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Waddington C, Enyimayew KA. A price to pay, part 2: The impact of user charges in the Volta region of Ghana. Int J Health Plann Manage 1990;5:287–312. 10.1002/hpm.4740050405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Asenso-Okyere WK, Anum A, Osei-Akoto I, et al. . Cost recovery in Ghana: are there any changes in health care seeking behaviour? Health Policy Plan 1998;13:181–8. 10.1093/heapol/13.2.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nyonator F, Kutzin J. Health for some? The effects of user fees in the Volta Region of Ghana. Health Policy Plan 1999;14:329–41. 10.1093/heapol/14.4.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ministry of Health. National Health Insurance Policy framework for Ghana: Revised Version. Accra. 2004. https://www.ghanahealthservice.org/downloads/NHI_policy framework.pdf (Accessed: 17 Dec 2017).

- 10. Parliament of Ghana. National Health Insurance Act, 2003 (Act 650). Insurance Act, 650. Accra, Ghana, 2003:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Parliament of Ghana. National Health Insurance Act, 2012 (Act 852. Accra, Ghana: Parliament of Ghana, 2012:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Attah Yeboah O. Per capita GDP increases to US$2,035 after rebasing …but has little effect on poverty. Business and Financial Times Online. 2018. https://thebftonline.com/2018/economy/per-capita-gdp-increases-to-us2035-after-rebasing-but-has-little-effect-on-poverty/ (Accessed 8 Apr 2019).

- 13. Nyavor G. Minimum wage goes up by 10%; now GHS10.65. 2018. https://www.myjoyonline.com/business/2018/July-27th/minimum-wage-goes-up-by-now-gh1065.php (Accessed 8 Apr 2019).

- 14. Aseweh Abor P, Abekah‐Nkrumah G, Abor J. An examination of hospital governance in Ghana. Leadersh Health Serv 2008;21:47–60. 10.1108/17511870810845905 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Andoh-Adjei FX, Nsiah-Boateng E, Asante FA, et al. . Perception of quality health care delivery under capitation payment: a cross-sectional survey of health insurance subscribers and providers in Ghana. BMC Fam Pract 2018;19:1–12. 10.1186/s12875-018-0727-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duku SKO, Nketiah-Amponsah E, Janssens W, et al. . Perceptions of healthcare quality in Ghana: Does health insurance status matter? PLoS One 2018;13:e0190911 10.1371/journal.pone.0190911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Development Planning Commission. 2008 Citizens’ assessment of the national health insurance scheme: towards a sustainable health care financing arrangement that protects the poor. Accra, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Health Insurance Authority. Active membership report for December 2018 (final as at April 1 2019. Accra, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19. National Health Insurance Authority. Benefits Package. National Health Insurance Scheme. 2019. http://www.nhis.gov.gh/benefits.aspx (Accessed 8 Apr 2019).

- 20. Kotoh AM, Van der Geest S. Why are the poor less covered in Ghana’s national health insurance? A critical analysis of policy and practice. Int J Equity Health 2016;15:1–11. 10.1186/s12939-016-0320-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kusi A, Enemark U, Hansen KS, et al. . Refusal to enrol in Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme: is affordability the problem? Int J Equity Health 2015;14:1–14. 10.1186/s12939-014-0130-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dake FAA. Examining equity in health insurance coverage: an analysis of Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme. Int J Equity Health 2018;17:1–10. 10.1186/s12939-018-0793-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dixon J, Tenkorang EY, Luginaah I. Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme: Helping the Poor or Leaving Them Behind? Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 2011;29:1102–15. 10.1068/c1119r [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana Living Standards Survey Round 6 (GLSS 6): Main Report. Accra 2014. http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/glss6/GLSS6_Main Report.pdf (Accessed 21 Aug 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ghana Statistical Service. Population & housing census: summary report of final results. Accra. 2012. http://statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/2010phc/Census2010_Summary_report_of_final_results.pdf.

- 26. Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana Living Standards Survey Round 6 (GLSS 6): Poverty Profile in Ghana (2005-2013). Accra. 2014. http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/glss6/GLSS6_Poverty Profile in Ghana.pdf (Accessed 29 Jan 2017).

- 27. Allin S, Masseria C, Sorenson C, et al. . Measuring inequalities in access to health care. A review of the indices. London Sch Econ Polit Sci 2007:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 28. O’Donnell O, Van Doorslaer DE, Wagstaff A, et al. . Analyzing health equity using household survey data: a guide to techniques and their implementation. Washington DC: The World Bank, 2008. www.worldbank.org (Accessed 22 Sep 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 29. Geifman N, Cohen R, Rubin E. Redefining meaningful age groups in the context of disease. Age 2013;35:2357–66. 10.1007/s11357-013-9510-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kastner M, Wilczynski NL, Walker-Dilks C, et al. . Age-specific search strategies for Medline. J Med Internet Res 2006;8:e25 10.2196/jmir.8.4.e25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kotoh AM, Aryeetey GC, Van der Geest S. Factors that influence enrolment and retention in Ghana’ National health insurance scheme. Int J Health Policy Manag 2018;7:443–54. 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Akazili J, Welaga P, Bawah A, et al. . Is Ghana’s pro-poor health insurance scheme really for the poor? Evidence from Northern Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:1–9. 10.1186/s12913-014-0637-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dror DM, Hossain SA, Majumdar A, et al. . What factors affect voluntary uptake of community-based health insurance schemes in low- and middle-income countries? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0160479 10.1371/journal.pone.0160479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Adebayo EF, Uthman OA, Wiysonge CS, et al. . A systematic review of factors that affect uptake of community-based health insurance in low-income and middle-income countries. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:1–13. 10.1186/s12913-015-1179-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van der Wielen N, Falkingham J, Channon AA. Determinants of National Health Insurance enrolment in Ghana across the life course: Are the results consistent between surveys? Int J Equity Health 2018;17:1–14. 10.1186/s12939-018-0760-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fenny AP, Kusi A, Arhinful DK, et al. . Factors contributing to low uptake and renewal of health insurance: a qualitative study in Ghana. Glob Health Res Policy 2016;1:1–10. 10.1186/s41256-016-0018-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Agyepong IA, Abankwah DNY, Abroso A, et al. . The “Universal” in UHC and Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme: policy and implementation challenges and dilemmas of a lower middle income country. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:1–14. 10.1186/s12913-016-1758-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Atinga RA, Abiiro GA, Kuganab-Lem RB. Factors influencing the decision to drop out of health insurance enrolment among urban slum dwellers in Ghana. Trop Med Int Health 2015;20:312–21. 10.1111/tmi.12433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029419supp001.pdf (208.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029419supp002.pdf (172.7KB, pdf)