Abstract

Objectives

To more clearly define the landscape of digital medical devices subject to US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversight, this analysis leverages publicly available regulatory documents to characterise the prevalence and trends of software and cybersecurity features in regulated medical devices.

Design

We analysed data from publicly available FDA product summaries to understand the frequency and recent time trends of inclusion of software and cybersecurity content in publicly available product information.

Setting

The full set of regulated medical devices, approved over the years 2002–2016 included in the FDA’s 510(k) and premarket approval databases.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome was the share of devices containing software that included cybersecurity content in their product summaries. Secondary outcomes were differences in these shares (a) over time and (b) across regulatory areas.

Results

Among regulated devices, 13.79% were identified as including software. Among these products, only 2.13% had product summaries that included cybersecurity content over the period studied. The overall share of devices including cybersecurity content was higher in recent years, growing from an average of 1.4% in the first decade of our sample to 5.5% in 2015 and 2016, the most recent years included. The share of devices including cybersecurity content also varied across regulatory areas from a low of 0% to a high of 22.2%.

Conclusions

To ensure the safest possible healthcare delivery environment for patients and hospitals, regulators and manufacturers should work together to make the software and cybersecurity content of new medical devices more easily accessible.

Keywords: medical devices, software, cybersecurity, FDA

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Cybersecurity issues related to medical devices have been documented in a number of individual cases, but the inclusion of cybersecurity content has never been considered systematically; we provide the first such analysis.

The study also provides a new application of the use of the Medical Text Indexer—a document classification algorithm from the US National Library of Medicine—for understanding the content of medical product descriptions.

The study’s primary limitation is that because the inclusion of cybersecurity content is not currently mandatory in Food and Drug Administration product summary documents, some devices may include cybersecurity features that cannot be accounted for by this analysis.

Introduction

The US National Research Council (NRC) defines cybersecurity as ’the technologies, processes, and policies that help to prevent and/or reduce the negative impact of events…that can happen as the result of deliberate actions against information technology by a hostile or malevolent actor'.1 In the USA, the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act of 2015 included healthcare provisions (Sec. 405) requiring the Department of Health and Human Services to report to Congress regarding the preparedness of the healthcare industry in responding to cybersecurity threats and lay out reporting requirements.2

In healthcare delivery and healthcare policy, cybersecurity comes up most readily in the context of health information technology. Such technology may include stand-alone software, such as electronic health record systems, or combinations of hardware and software, such as those seen in modern pacemakers, blood glucose monitors and CT scanners. In the latter category, many digital products pose sufficient risk to patients as to require regulatory approval for use. In the USA, products containing both software and hardware are regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Importantly, digital medical devices—those that contain software and/or digital networking capabilities—are quickly becoming embedded in all facets of medical care. However, the prevalence of software and the inclusion of cybersecurity features among already-marketed regulated medical devices have not been previously investigated.

At the same time, there have been several recent examples of software-related medical device vulnerabilities,3 4 including potential use of a pacemaker remote monitoring system to issue malicious programming commands.5 These devices may also place healthcare facilities at risk6: A recent report from a cybersecurity firm highlighted the fact that 90% of hospitals had been targeted by cybercriminals in the past 2 years and that 17% of these documented attacks had been facilitated by internet-connected medical devices.7 The May 2017 WannaCry ransomware attack was the largest cyberattack to affect the UK’s National Health Service, impacting 34% of trusts and disrupting some medical devices, including a subset of MRI scanners and devices to test blood and tissue samples.8 9

In recognition of these risks, the FDA has issued both premarket and post-market regulatory guidance10 11 on medical device cybersecurity while actively engaging industry and outside experts in addressing post-market cybersecurity concerns. To more clearly define the landscape of digital medical devices subject to FDA oversight, this analysis leverages publicly available FDA documents to characterise the prevalence and trends of software and cybersecurity features in regulated medical devices.

Methods

Data sources

We analysed data from publicly available FDA product summaries, identified from searchable documents published by the FDA at the time of each new device’s clearance or approval for marketing.12 13 Such summaries have supported previous analyses,14 15 and as outlined by FDA guidance, these summaries contain information such as indications for use, a detailed device description (including device design, material use and physical properties), contradictions/warnings/precautions and clinical evidence supporting the regulatory assessment of safety and effectiveness.16 17 Along with the FDA-approved product label (with which a summary will share many pieces of important information), summary documents represent key pieces of publicly available information about medical devices that have been granted marketing approval or clearance in the USA.

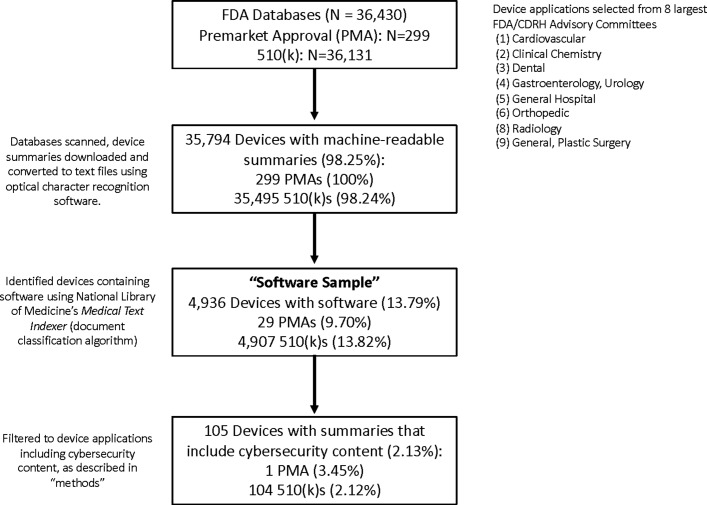

We used the FDA’s 510(k) and premarket approval (PMA) databases to identify all new device clearances and approvals from 2002 to 2016, respectively14 15 (see online supplementary material table 1). In brief, under the FDA’s risk-based framework for premarket evaluation, high-risk devices are evaluated under the PMA pathway, which includes demonstration of clinically relevant safety and effectiveness. By contrast, medium-risk devices are generally assessed via the ‘510 k’ pathway, which evaluates whether new safety or effectiveness concerns are raised by the device at issue compared with a ‘substantially equivalent’ device already on the market.18 19 Online supplementary material figure 1 presents a brief overview of these pathways and their typical components. In the 510(k) and PMA databases, we identified the eight largest medical device categories by advisory committee of assignment. Advisory committees correspond largely to medical specialties (eg, committees exist for cardiovascular, radiological and orthopaedic devices) and the eight largest committees accounted for over 75%14 15 of all regulated devices that came to market over this period of time (see figure 1 for a summary of how the analysis sample was identified). Modifications to already-marketed devices approved via the ‘PMA supplement’ pathway20 were excluded.

Figure 1.

Assembly of analysis sample and results. CDRH, Center for Devices and Radiological Health; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; PMA, premarket approval.

bmjopen-2018-025374supp001.pdf (355KB, pdf)

We used an automated Python script to batch download all associated product summaries and applied ABBYY FineReader optical character recognition software (ABBYY, Milpitas, CA, USA) to convert these Portable Document Format (PDF) files into machine-readable text files.

Analysis sample

We used the US National Institute of Health’s National Library of Medicine (NLM) Medical Text Indexer 21 (MTI) to identify digital devices as those referencing and/or describing software in their product summaries. The MTI uses natural language processing algorithms that take free text as input and provide medical subject indexing recommendations, based on the Medical Subject Headings vocabulary22 established by the NLM, as output. From a regulatory perspective, products containing software must describe this in their summaries (see above). Indeed, many device summaries contain a short section of the document that is dedicated to describing the product’s software (eg, as seen for the Medtronic MiniMed 670G Automated Insulin Delivery System).23 We used the sample of summaries that were flagged by the MTI for including the medical subject of ‘software’ as our analysis sample of digital devices (‘software sample’). In sensitivity analysis, an alternative, keyword-based definition was considered and did not impact findings (table 1 and online supplementary material figure 2). For each product in the software sample, we recorded each device’s FDA decision date (ie, the year in which the product came to market), its regulatory approval pathway (510(k) or PMA) and the reviewing advisory committee.

Table 1.

Number of devices with machine-readable summaries by FDA/CDRH Advisory Committee and year, share with software and share of software sample with cybersecurity content by Advisory Committee

| Year | FDA/CDRH Advisory Committee | ||||||||

| Clinical chemistry | Cardiovascular | Dental | Gastroenterology, urology | General hospital | Orthopaedic | Radiology | General, plastic surgery | Totals | |

| (CH) | (CV) | (DE) | (GU) | (HO) | (OR) | (RA) | (SU) | ||

| 2002 | 216 | 436 | 318 | 215 | 328 | 403 | 290 | 367 | 2573 |

| 2003 | 192 | 441 | 295 | 233 | 329 | 389 | 329 | 357 | 2565 |

| 2004 | 204 | 395 | 284 | 195 | 270 | 464 | 345 | 319 | 2476 |

| 2005 | 155 | 389 | 245 | 166 | 262 | 480 | 310 | 331 | 2338 |

| 2006 | 197 | 412 | 293 | 142 | 244 | 442 | 338 | 362 | 2430 |

| 2007 | 153 | 358 | 283 | 160 | 257 | 444 | 271 | 319 | 2245 |

| 2008 | 149 | 387 | 279 | 139 | 207 | 477 | 325 | 370 | 2333 |

| 2009 | 130 | 442 | 268 | 155 | 254 | 432 | 290 | 316 | 2287 |

| 2010 | 121 | 390 | 245 | 157 | 280 | 428 | 235 | 312 | 2168 |

| 2011 | 163 | 428 | 258 | 141 | 241 | 542 | 347 | 285 | 2405 |

| 2012 | 155 | 426 | 240 | 166 | 282 | 551 | 344 | 302 | 2466 |

| 2013 | 185 | 428 | 235 | 153 | 202 | 554 | 346 | 301 | 2404 |

| 2014 | 130 | 400 | 225 | 199 | 245 | 583 | 385 | 342 | 2509 |

| 2015 | 108 | 392 | 244 | 179 | 174 | 575 | 340 | 322 | 2334 |

| 2016 | 95 | 368 | 230 | 171 | 204 | 464 | 375 | 354 | 2261 |

| Totals | 2353 | 6092 | 3942 | 2571 | 3779 | 7228 | 4870 | 4959 | 35 794 |

| Share with software (‘software sample’) | 9.14% | 18.99% | 4.59% | 8.01% | 4.97% | 1.36% | 52.28% | 6.96% | 13.79% |

| Share of software sample with cybersecurity content | 7.91% | 2.51% | 1.66% | 0.00% | 2.13% | 0.00% | 2.04% | 0.00% | 2.13% |

CDRH, Center for Devices and Radiological Health; FDA, Food and Drug Administration.

Characterisation of cybersecurity features

The ‘cybersecurity features’ of digital medical devices can take on a number of forms, each of which can address the risks of actions by malevolent parties. Such cybersecurity features may include characterisations or descriptions of a digital product’s defensive abilities (eg, data encryption), an ability to respond to a security breach should it be attempted (eg, antivirus software), or the ability to detect a breach that has already occurred (eg, penetration testing).

We searched each of the summaries in the software sample for a pre-specified list of keywords related to cybersecurity content (online supplementary material table 2) and documented use of these keywords (yes/no) in each product summary. These keywords and phrases were selected a priori from terminology glossaries from the US National Initiative for Cybersecurity Careers and Studies, the FDA’s guidance on cybersecurity for medical devices, the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST 4009/NISTIR 7298) Glossary,24 and the Manufacturer Disclosure Statement for Medical Device Security, a multi-stakeholder devised form designed to give manufacturers a mechanism of disclosing security-related product information to healthcare providers.25

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not directly involved in the design of this retrospective study of publicly available regulatory documents. However, popular media accounts of recent cybersecurity concerns in medical devices have brought this previously obscure topic to the attention of a wide public audience, particularly the millions of patients living with potentially affected devices.26–28

Data analysis

For each year, we identified the software sample and calculated the number and percentage (share) of devices that included cybersecurity content by advisory committee and overall. We compared the percentage of devices with cybersecurity content, as identified by keywords. Using χ2 tests, we looked at differences between the two major regulatory approval pathways and in earlier versus later years, by comparing the first decade of the period of observation to the final 2 years.

To validate our automated search protocol, we manually reviewed 100 summaries. We selected 50 summaries from the software sample that were identified as containing cybersecurity information, and 50 that were identified as having no such content to confirm text scraping methods. Discrepancies were reviewed by group assent. We further validated our method of identifying devices containing software by electronically scanning all product summaries for the keyword ‘software’ and using these results to assess the sensitivity and specificity of the MTI-defined software sample (online supplementary material).

All statistical analyses were conducted in STATA V.14.2 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

A total of 36 430 new devices were identified (figure 1) and of those, 35 794 (98.25%) had product summaries that could be converted to machine-readable text. From this sample, 4936 new devices (13.79%) were identified by the MTI as including software (9.70% of PMA devices and 13.82% of 510(k) devices. Within the software sample, we found that only 2.13% of devices had product summaries that included cybersecurity content (3.45% of PMA devices and 2.12% of 510(k) devices included cybersecurity content in their summaries; however, differences between PMA and 510(k) devices were not statistically significant; p=0.62). Manual review confirmed that 100% of summaries included the keyword(s) found by our automated programme. Relative to our keyword-based validation exercise, the MTI had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 94.8%, making it a more conservative measure.

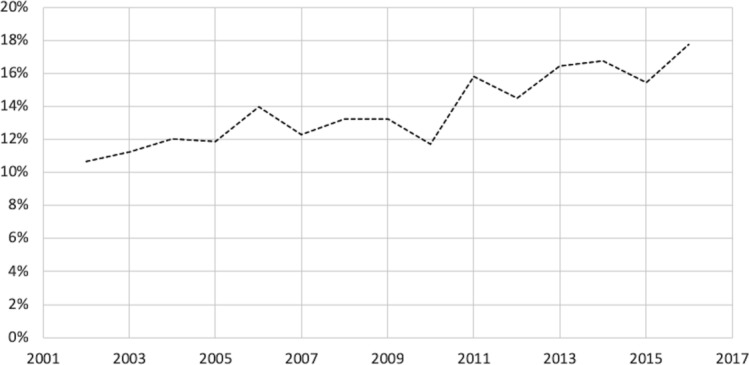

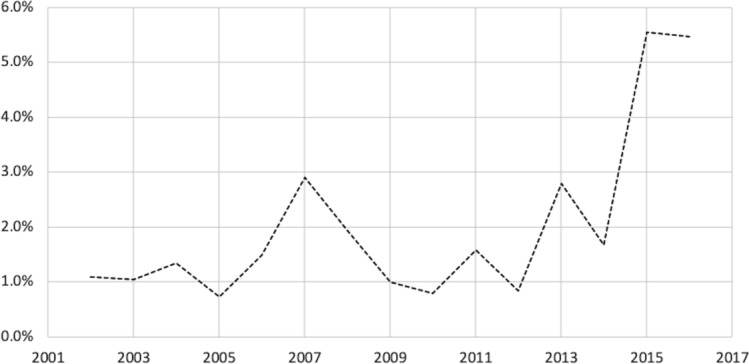

Figure 2 presents the share of devices with software over time, whereas figure 3 presents the share of devices in the software sample that included cybersecurity content in their product summaries over the same period. The overall share of devices including cybersecurity content was higher in recent years, growing from an average of 1.4% in the first decade of our sample to an average of 5.5% in 2015 and 2016, the most recent years included in the sample (p=0.0181). The share of devices including cybersecurity content also varied across regulatory areas from a low of 0% across all years in gastroenterology/urology devices, orthopaedic devices and general/plastic surgery devices, to a high of 22.2% among general hospital devices in 2016 (results not shown). Online supplementary table 2 provides additional detail of the frequencies of individual keywords in the sample.

Figure 2.

Share of new devices with software (‘software sample’).

Figure 3.

Share of software sample with cybersecurity content.

Discussion

Summary

This study leverages a novel methodology to create an analysable dataset from public documents describing newly marketed medical devices. We found that software is an increasingly common component of newly approved or cleared devices, while cybersecurity content in the devices’ publicly available product summaries remains rare.

The absence of cybersecurity information for those selecting devices is a concern because it prevents both patients and clinicians from making fully informed decisions about the potential risks associated with the products that they use. This dearth of information may also lead to patients and clinicians to unknowingly adopt products that fail to incorporate appropriate cybersecurity measures. For patients, the risks of software vulnerabilities to safety and privacy can be devastating. A recent study found that hundreds of US medical device recalls have been attributed to software defects—including several recalls of the highest risk to patients.29 Furthermore, data breaches are already a serious concern for the exposure of sensitive patient data: tens of millions of records from entities covered by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act have already experienced breaches, with the majority resulting from overt criminal activity, making this risk all the more alarming.30

As more and more aspects of healthcare are digitised, the cybersecurity of our healthcare infrastructure—including medical devices—will be increasingly essential to delivering safe and effective care. Recent events such as the emergence of pacemaker vulnerabilities have highlighted both the public health implications of information security31 and importance of device security.6 Additionally, the recent security flaws discovered in widely used computer processors highlight the fact that new threats continue to emerge32 and scholars have highlighted medicine as a domain where adversarial attacks may be particularly likely to unfold,33 with the opportunity for significant clinical impact. Indeed, the NRC has written that ’from the standpoint of an individual system or network operator, the only thing worse than being penetrated is being penetrated and not knowing about it'.1 This study is an important first step in understanding the public, transparent reporting of cybersecurity features included in the software embedded in moderate-risk and high-risk medical devices. Indeed, our characterisation of the growing importance of software among regulated devices should encourage policymakers to buttress FDA’s resources accordingly, including support for partnerships with the Department of Homeland Security and other government, academic and industry partners focused on anticipating and responding to emerging threats to patients and public health.

Limitations

The key limitation of this study is that the information we collected is not a mandatory component of the documents considered. As a result, product summaries may not include all relevant details of a device’s design with respect to cybersecurity. While this information may have been present in other places, such as proprietary applications or the full, confidential FDA dossier, device summaries represent some of the primary documents available for public review, and therefore play an important role in educating stakeholders, such as clinicians, purchasing managers, patients and administrators of healthcare systems about the strength of safety and effectiveness evidence when a new product comes to market. The potential for unobserved information related to cybersecurity content is the key weakness of this study; however, the study’s key strength is that it is, to our knowledge, the first to take a large-scale approach to characterising the availability of cybersecurity content among approved medical devices.

Policy implications

These findings help define the current landscape of medical device software and cybersecurity features, and suggest an opportunity to better inform healthcare professionals, those engaging in device procurement on behalf of hospitals and healthcare systems, and patients, on the cybersecurity protections embedded in medical devices. In particular, recently retired FDA Commissioner, Dr Scott Gottlieb, has publicly acknowledged the importance of the availability of cybersecurity information, noting that ‘Securing medical devices from cybersecurity threats cannot be achieved by just the FDA alone’ and that ’every stakeholder – manufacturers, hospitals, health care providers, cybersecurity researchers and gov[ernment] entities [has] a unique role to play in addressing these modern challenges'.34 In the fourth quarter of 2018, in response to the need to ‘ensure the health care sector is well positioned to proactively respond when cyber vulnerabilities are identified',35 the FDA released updated guidance on the content of premarket submissions for the management of cybersecurity in medical devices10 and the US Department of Health and Human Services similarly recently released voluntary guidance on cybersecurity practices for healthcare organisations.36 Ongoing opportunities for the exchange of ideas and best practices among regulators, practitioners and cybersecurity experts, such as those recently hosted by the FDA on the ‘management of cybersecurity in medical devices'37 and collaborations between the security research and medical device communities38 will be valuable for ensuring public health, and a better-informed public and medical community will be crucial to ensuring the safety of medical devices moving forward.

Our findings also support the case for recent proposals by US regulators to include a cybersecurity ‘bill of materials’ in the submission of new medical devices. The proposal calls for ’principles and approaches [that] are broadly applicable to all medical devices and are intended to be consistent with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity'.10 Such a standardised approach would represent an important step in addressing the cybersecurity information deficit that we have documented here. Furthermore, many individual hospitals and other purchasers of medical devices currently perform independent information security assessments of medical devices—a slow, resource intensive, and costly process. Standardising the information security review process and making the results available publicly would bring substantial efficiencies for medical device vendors and healthcare organisations.

Looking ahead

In an increasingly digitised healthcare ecosystem, manufacturers will face increasing demands for product safety in the form of cybersecurity protections. Moreover, stakeholders will increasingly seek out information about the safety features of new products. Regulators and manufacturers should collaborate to make the software and cybersecurity content of new products more easily accessible, and should continue to work together to determine which cybersecurity content should be disclosed and required for regulatory clearance and approval of new products moving forward. It will also be important for future researchers to closely track the availability of cybersecurity content in newly approved medical devices and to explore whether the publication of such content impacts the product utilisation decisions of patients and healthcare providers.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: ADS designed the study in consultation with WJG, ABL and DBK. ADS collected the data from public sources and performed the primary analysis. All authors had full access to the data and analysis programmes for this study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. All authors wrote the manuscript.

Funding: The Harvard Business School Division of Research and Faculty Development supported the data collection for this study. Dr Stern is supported by the Kauffman Junior Faculty Fellowship and Dr Kramer is supported by the Greenwall Faculty Scholars Program in Bioethics.

Competing interests: ABL is a member of the Abbott Medical Device Cybersecurity Council. DK is supported by the Greenwall Faculty Scholars Program in Bioethics, is a consultant to Circulatory Systems Advisory Panel of the Food and Drug Administration, and has provided consulting to the Baim Institute for Clinical Research for clinical trials of medical devices (unrelated to the study topic).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Statistical code and the full dataset are available at https://github.com/arieldora/SternCybersecurityContent.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. National Research Council. At the Nexus of Cybersecurity and Public Policy: Some Basic Concepts and Issues [Internet]. The National Academies Press. 2014. 10.17226/18749 (accessed 10 Jul 2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. Burr R. S.754 - 114th Congress (2015-2016): To improve cybersecurity in the United States through enhanced sharing of information about cybersecurity threats, and for other purposes. 2015. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/754 (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 3. Blau M. Hospitals brace for security risks that could come with using wearables for patient care [Internet]. STAT. 2017. https://www.statnews.com/2017/08/04/hospitals-security-risks-wearables/ (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 4. Kuchler H. Medical device makers wake up to cyber security threat. Financial Times. 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/00989b9c-7634-11e7-90c0-90a9d1bc9691 (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 5. Kramer DB, Fu K, Concerns C. and Medical Devices: Lessons From a Pacemaker Advisory. JAMA 2017;318:2077–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fox-Brewster T. Medical Devices Hit By Ransomware For The First Time In US Hospitals [Internet]. Forbes. 2017. https://www.forbes.com/sites/thomasbrewster/2017/05/17/wannacry-ransomware-hit-real-medical-devices/#4a76dbe8425c (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 7. ZingBox. IoT guardian for the healthcare industry [Internet]. 2016. http://www.zingbox.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/ZingBox_WP_IoT-Guardian-for-the-Healthcare-Industry.pdf (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 8. Hughes O. WannaCry impact on NHS considerably larger than previously suggested [Internet]. Digital Health. 2017. https://www.digitalhealth.net/2017/10/wannacry-impact-on-nhs-considerably-larger-than-previously-suggested/ (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 9. Department of Health. Investigation: WannaCry cyber attack and the NHS [Internet]. 2017 Oxtober. Report No.: HC 414. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Investigation-WannaCry-cyber-attack-and-the-NHS.pdf (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 10. Food and Drug Administration. Content of Premarket Submissions for Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices - Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/guidancedocuments/ucm356190.pdf (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 11. Postmarket Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices - Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/guidancedocuments/ucm482022.pdf (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 12. 510(k) Premarket Notification. 2017. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfPMN/pmn.cfm (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 13. Premarket Approval (PMA). 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfPMA/pma.cfm (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 14. Zheng SY, Dhruva SS, Redberg RF. Characteristics of Clinical Studies Used for US Food and Drug Administration Approval of High-Risk Medical Device Supplements. JAMA 2017;318:619–25. 10.1001/jama.2017.9414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dhruva SS, Bero LA, Redberg RF. Strength of study evidence examined by the FDA in premarket approval of cardiovascular devices. JAMA 2009;302:2679–85. 10.1001/jama.2009.1899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Content of a 510(k). 2017. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/HowtoMarketYourDevice/PremarketSubmissions/PremarketNotification510k/ucm142651.htm#link_7 (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 17. PMA Application Contents. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/HowtoMarketYourDevice/PremarketSubmissions/PremarketApprovalPMA/ucm050289.htm#ssed (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 18. Kramer DB, Kesselheim AS. User fees and beyond--the FDA Safety and Innovation Act of 2012. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1277–9. 10.1056/NEJMp1207800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kramer DB, Xu S, Kesselheim AS. Regulation of medical devices in the United States and European Union. N Engl J Med 2012;366:848–55. 10.1056/NEJMhle1113918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rome BN, Kramer DB, Kesselheim AS. FDA approval of cardiac implantable electronic devices via original and supplement premarket approval pathways, 1979-2012. JAMA 2014;311:385–91. 10.1001/jama.2013.284986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. NLM Medical Text Indexer (MTI). 2018. https://ii.nlm.nih.gov/MTI (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 22. MeSH [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 23. Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Data (SSED) [Internet]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf10/P100034b.pdf (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 24. Kissel R. Glossary of Key Information Security Terms [Internet]. 2013:1–218 http://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ir/2013/NIST.IR.7298r2.pdf (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 25. Manufacturer Disclosure Statement for Medical Device Security (MDS2). 2017. http://www.himss.org/resourcelibrary/MDS2 (accessed 10 Jul 2018).

- 26. CBS News. How medical devices like pacemakers and insulin pumps can be hacked [Internet]. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/cybersecurity-researchers-show-medical-devices-hacking-vulnerabilities/ (accessed 29 Jan 2019).

- 27. Gellman L. Insecure Medical Devices Vulnerable to Malicious Hacking [Internet]. http://nymag.com/intelligencer/2018/08/insecure-medical-devices-vulnerable-to-malicious-hacking.html (accessed 29 Jan 2019).

- 28. Innes S. “Ethical hackers” are working to warn physicians about cyberattacks [Internet]. 2018. https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/arizona-health/2018/12/27/ethical-hackers-warn-physicians-cyberattacks-christian-dameff-arizona-college-medicine-jeff-tully/2277625002/ (accessed 29 Jan 2019).

- 29. Ronquillo JG, Zuckerman DM. Software-Related Recalls of Health Information Technology and Other Medical Devices: Implications for FDA Regulation of Digital Health. Milbank Q 2017;95:535–53. 10.1111/1468-0009.12278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu V, Musen MA, Chou T. Data breaches of protected health information in the United States. JAMA 2015;313:1471–3. 10.1001/jama.2015.2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gordon WJ, Fairhall A, Landman A. Threats to Information Security - Public Health Implications. N Engl J Med 2017;377:707–9. 10.1056/NEJMp1707212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Finlayson SG, Won Chung H, Kohane IS, et al. Adversarial Attacks Against Medical Deep Learning Systems. arXiv [Internet]. 2018. https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.05296 (accessed 29 Jan 2019).

- 33. Metz C, Perlroth N. Researchers Discover Two Major Flaws in the World’s Computers. The New York Times [Internet]. 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/03/business/computer-flaws.html (accessed 10 Jul 2019).

- 34. Scott Gottlieb MD. on Twitter: “4/4 Securing medical devices from cybersecurity threats cannot be achieved by just the #FDA alone. Every stakeholder—manufacturers, hospitals, health care providers, cybersecurity researchers and govt entities – all have a unique role to play in addressing these modern challenges” [Internet]. 2018. https://twitter.com/SGottliebFDA/status/1046847875840450560 (accessed 29 Jan 2019).

- 35. FDA In Brief. FDA proposes updated cybersecurity recommendations to help ensure device manufacturers are adequately addressing evolving cybersecurity threats [Internet]. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/FDAInBrief/ucm623624.htm (accessed 29 Jan 2019).

- 36. Health Industry Cybersecurity Practices: Managing Threats and Protecting Patients. 36. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/405d/Documents/HICP-Main-508.pdf (accessed 29 Jan 2019).

- 37. Workshops & Conferences (Medical Devices) > Public Workshop. Content of Premarket Submissions for Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices January 29-30. 2019. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/NewsEvents/WorkshopsConferences/ucm623171.htm (accessed 29 Jan 2019).

- 38. #WeHeartHackers. A collaborative movement between the medical device and security researcher communities. http://wehearthackers.org/ (accessed 29 Jan 2019).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025374supp001.pdf (355KB, pdf)