Abstract

BN/CC isosterism has emerged as a viable strategy to expand the chemical space of organic molecules. In particular, the application of BN/CC isosterism to arenes has received significant attention due to the vast available chemical space provided by aromatic hydrocarbons. The synthetic efforts directed at assembling novel aromatic BN heterocycles have resulted in the discovery of new properties and functions in a variety of fields including biomedical research, medicinal chemistry, materials science, catalysis, and organic synthesis. This tutorial review specifically covers recent advances in synthetic technologies that functionalize assembled boron–nitrogen (BN) heterocycles and highlights their distinct reactivity and selectivity in comparison to their carbonaceous counterparts. It is intended to serve as a state-of-the-art compendium for readers who are interested in the reaction chemistry of BN heterocycles.

Introduction

Arenes are a ubiquitous motif found across many fields of chemistry, and accordingly the last two decades have seen significant research efforts devoted to BN/CC isosterism in arenes.1 Replacing a CC bond with a BN bond in an arene has been demonstrated to be a viable strategy for expanding chemical space. Introduction of a polarized BN bond fundamentally alters the properties of a given molecule; in this way, BN isosteres of arenes, or azaborines, have advanced research in the fields of biomedical research, materials science, and catalysis.2–4 The burgeoning of applications of azaborines is a direct result of advances in the synthetic access to these heterocycles.

The aim of this tutorial review is to provide all of the available methods for the late-stage functionalization of 1,2-azaborines, including monocyclic 1,2-azaborines as well as BN-naphthalenes (with connected BN units) and higher-order BN-polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). In this context, late-stage functionalization means any method used to install a functional group after the azaborine heterocycle itself has been synthesized. This review serves as a practical guide for engaging in azaborine research and covers the synthetic toolbox available for functionalizing each azaborine.

While much progress is yet to be made, the functionalization of azaborines has seen substantial development in the past few years. Some of this progress has come from harnessing the unique reactivity of 1,2-azaborines but the majority of developments in late-stage functionalization are a result of adapting established arene chemistry to BN-containing substrates. Regardless of the type of reactivity, developing methods to elaborate the azaborine core is essential to increasing the number of potential applications. Azaborine chemistry as an emerging area provides both challenges and opportunities to the practicing synthetic chemist. The susceptibility of certain BN-compounds to degradation by water or oxidation represents a significant hurdle in developing new synthetic methods. On the other hand, the presence of the BN bond provides access to inherent selectivity not available to all-carbon compounds, as the reduction in the symmetry of the molecule renders each position of the 1,2-azaborine electronically distinct. This tutorial review is organized by the BN heterocyclic structural motif followed by reaction types.

1,2-Azaborines

Electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS)

One of the hallmark reactions of aromatic compounds is electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS). In 2007, Ashe first demonstrated that monocyclic 1,2-azaborines could undergo EAS. Compound 1 undergoes rapid reaction with molecular bromine, installing a bromine with complete regioselectivity at the C3 position (Scheme 1a).5 According to calculations,6 the C3 and C5 positions of the 1,2-azaborine are the most electron-rich, and are thus expected to undergo electrophilic attack. Halogenation opens a suite of well-developed reactions for converting aryl halides into a host of functionalized arenes (vide infra). The building block 1,2-azaborine 3† also reacts with bromine to afford C3–Br 4 in high yield (Scheme 1b).7 This triply orthogonal 1,2-azaborine synthon can be further functionalized at the N, B, and C3 positions. Fang developed an alternative method for bromination with CuBr2 as the bromine source and acetyl chloride as an activating agent (Scheme 1c).8 In another publication by the Fang group, the C3 position of 5 underwent electrophilic attack with NIS activated by AlCl3 in high yield (Scheme 1d).9

Scheme 1.

Halogenation of various 1,2-azaborines through EAS.

While the C3 position of the 1,2-azaborine attacks halogen electrophiles, the C5 position tends to engage in Friedel–Crafts reactivity. Ashe also reported the first example of C5 substitution; Friedel–Crafts acetylation of compound 1 proceeds in poor yield in the presence of acetic anhydride and SnCl4 (Scheme 2a).5 The 10% yield of acetylated 8 and messy product mixture suggest significant side-reactivity. Fang built on the work of Ashe to develop an improved Friedel–Crafts acylation method for N-methyl, B-mesityl-substituted azaborine 5 (Scheme 2b).9 The mesityl (Mes = 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl) group is known to provide robustness to the azaborine heterocycle against unwanted side reactions such as oxidative degradation. AgBF4 activates various acylchlorides at 50 °C in CH2Cl2 toward Friedel–Crafts reaction with 1,2-azaborines 5 or 7.

Scheme 2.

Acylation of 1,2-azaborines at C5 position.

Preference for substitution at the C5 instead of the C3 position may be explained by the presence of the bulky mesityl group. Intriguingly, when the reaction was performed with AlCl3, no regioselectivity was observed. The substrate scope for the AgBF4 mediated reaction includes alkanoyl, alkenoyl, and aroyl chlorides as well as one example of a carbamic chloride to furnish compounds 9a–i. Electron-deficient substrates are a limitation of this method, as they could not be activated with AgBF4.

Other types of C5 substitution reactions are illustrated in Scheme 3. As part of their acylation work, the Fang group investigated the reaction between 5 and methacryloyl chloride, which produced BN-indanone analogue 10 (Scheme 3a).9 According to the proposed mechanism, 5 first undergoes C5 Friedel–Crafts acylation followed by a Nazarov cyclization at the C6 position. In another report, Fang and co-workers developed a procedure for the regioselective nitration of 5 and 6 (Scheme 3b).8 In the presence ofa metal-nitrate hydrate and acetyl chloride a nitro group is installed at the C5 position in good yield, likely via a radical mechanism. In the presence of radical scavengers compound 5 produced the C5-acetylated compound 9a. Ashe demonstrated that N,N-dimethyl-methyleneiminium chloride reacts with 1 in refluxing acetonitrile to afford 13 in moderate yield (Scheme 3c),5 adding another example of a C5 selective substitution reaction.

Scheme 3.

Other C5 functionalization methods by Ashe and Fang.

C–H borylation

In addition to halogens, boronate esters are a versatile platform for forming bonds to arenes. C–H borylation proceeds at room temperature with complete regioselectivity for the most acidic C6–H position of parent azaborine 14a (Scheme 4).10 The preference for borylating the 1,2-azaborine ring is maintained in the presence of a phenyl ring within the same molecule as in 14d, as well as in direct competition experiments with benzene itself. Various groups are tolerated in the reaction, including alkyl, aryl, and the alkoxide group at the boron position as well as the Br group at the C3 position (e.g., 14h).11

Scheme 4.

Substrate table for the C–H borylation of 1,2-azaborines.

Cross-coupling

Optimization of a Suzuki cross-coupling for 1,2-azaborines followed the development of C–H borylation. Many substituted phenyl bromides, heteroaryl bromides, and one example of an alkenyl bromide undergo cross-coupling with C6 borylated azaborines 15 (Scheme 5a).10 The cross-coupled products 16 with B-alkyl or B-aryl substituents were prepared with Pd(dppf)Cl2 as the catalyst and KOH as the base at 80 °C. 1,2-Azaborine can also be coupled to itself by reacting borylated 15f with brominated 14h to form dimer 14i (Scheme 5a).11 Another iteration of borylation and subsequent coupling between dimer 15i and brominated 14h produces trimer 17. With some adjustment to the reaction conditions, C6 borylated, C3 brominated 15h functions as a monomer in a polymerization process (via Suzuki coupling) to afford polymer 18 (Scheme 5b).11

Scheme 5.

(a) Suzuki cross-coupling of borylated 1,2-azaborines. (b) Polymerization of C6-borylated, C3-brominated monomer via Suzuki cross-coupling.

1,2-Azaborines bearing B–H or B–OR substitution generally required milder conditions, as these compounds are more susceptible to hydrolysis (Scheme 6). Thus, the borylated parent 1,2-azaborine 15a undergoes the cross-coupling reaction at room temperature promoted by the more mild base Na2CO3 solubilized with minimal water.10 Under the room temperature conditions, compound 15e maintains its n-butoxide substituent at the boron position in an n-BuOH/H2O solvent system. While the acidic N–H bond could theoretically participate in a competitive Buchwald–Hartwig C–N coupling, only the Suzuki coupling products were observed.

Scheme 6.

Suzuki cross-coupling of B-H and B-O-nBu substituted 1,2-azaborines.

Just as C–H borylation opened up the possibility for Suzuki coupling of 1,2-azaborines at the C6 position, so too did bromination provide access to cross-coupling methods at the C3 position. For synthon 4 (Scheme 7), Negishi cross-coupling was selected due to the ready availability and low toxicity of zinc reagents as well as their functional group compatibility.7 In addition, Negishi couplings do not require borophilic additives. The catalyst Pd(P-t-Bu3)2 promotes cross-coupling between alkyl, alkenyl, and aryl zinc halides and 4 at room temperature (Scheme 7). The labile B–Cl bond remains intact, and thus the boron position can be subsequently functionalized (vide infra). No background reactivity with zincates was observed in the absence of catalyst.

Scheme 7.

Negishi cross-coupling of C3–Br 1,2-azaborine 4.

Nucleophilic substitution

For hydrocarbon-based arenes and other heterocycles, nucleophilic substitutions typically require highly activated substrates (e.g. 2-fluoropyridine) and/or harsh conditions involving strong nucleophiles and high temperatures.12 The vacant p-type orbital on the boron atom of the 1,2-azaborine renders the boron position susceptible to nucleophilic attack. Thus, more mild conditions and a greater variety of nucleophiles can typically be employed with BN heterocycles. This section details numerous examples of nucleophilic substitution at the boron atom as well as selected examples of substitution-type reactions at the C3 position.

In 2011 Liu and coworkers investigated the reactivity of the parental 1,2-azaborine 14a with strong nucleophiles and developed a one-pot method for disubstitution at the N and B positions of the 1,2-azaborine.13 Adding two equivalents of a strong nucleophile such as n-BuLi to parent 1,2-azaborine 14a induces the boron-hydride to act as a leaving-group, leading to a substitution reaction (Scheme 8a, entries 1–10). One equivalent of the n-BuLi deprotonates the acidic N–H, and the resulting amide can then be quenched with an electrophile, yielding monosubstituted 14 (E = H) or disubstituted 20 (E ≠ H). The disubstitution reaction with respect to 1,2-azaborines was later expanded to include an alkoxide leaving-group on boron (Scheme 8a, entries 11–14).14 Suitable nucleophiles include alkyl, alkenyl, aryl, and alkynyl organometallic reagents. Electrophiles susceptible to attack by the nitrogen atom of the 1,2-azaborine in this one-pot procedure include proton, chlorotrimethylsilane, iodomethane, and benzyl-chloride. While alkoxides are suitable nucleophiles for the parent 14a they are unable to displace the n-butoxide group in 14e. Instead, ligand exchange between the 1,2-azaborine-alkoxide 14e and borontrichloride in situ generates the more reactive B-Cl 14n, which then can undergo substitution with potassium phenoxide, potassium phenylacetate, or the hindered diphenylmethyllithium (Scheme 8b).14

Scheme 8.

(a) Nucleophilic substitution reaction of 1,2-azaborine. (b) In situ generation of N-H-B-Cl-1,2-azaborine 14n followed by nucleophilic substitution at boron.

Many examples now exist for the simple nucleophilic displacement at the boron position of a 1,2-azaborine, in particular when the leaving-group is a halide. In 2007, the Liu group introduced N-ethyl-B-Cl substituted 1,2-azaborine synthon 21 to allow general access to B-substituted 1,2-azaborines.15 The scope with respect to the nucleophiles is quite broad, including various N-,O-based nucleophiles and alkyl, alkenyl, and aryl organometallic reagents (Scheme 9a). In addition to the N-Et derivatives 1,15 examples of N-Me-(compounds 5),9,16 and N-Bn-substituted 1,2-azaborine (compounds 24)17 have been reported. Substitution at boron is also possible with nucleophiles generated in situ with non-nucleophilic bases such as KH and Et3N (Scheme 9b).15 Phosphides can also displace the chloride leaving-group, forming azaborine-containing triaryl-phosphine ligands 5b and 5c (Scheme 9c).18 Neutral nucleophiles are in general not capable of displacing the chloride from the boron atom. However, when the chloride is replaced with the triflate (OTf−) leaving-group, pyridines become suitable nucleophiles to form cationic adducts 26 from the B-OTf-substituted 1,2-azaborine 25 (Scheme 10).19

Scheme 9.

(a) Nucleophilic substitution of N-alkyl-B-Cl 1,2-azaborines. (b) Substitution with in situ generated nucleophiles. (c) Synthesis of azaborine-containing triarylphosphine ligands.

Scheme 10.

Preparation of azaborine cations from B-OTf-substituted 1,2-azaborine 25.

The commercially available N-TBS-B-Cl 1,2-azaborine 3 has emerged as a foundational building block for the chemistry of monocyclic 1,2-azaborines and thus deserves special mention. In addition to the chloride leaving-group on boron, the TBS protecting group on nitrogen serves as a handle for late-stage functionalization. Compound 3 can be difunctionalized in a simple process: nucleophilic addition at the boron position followed by removal of the N-TBS group and subsequent functionalization at the nitrogen position. The scope of nucleophiles includes alkyl, aryl, alkynyl and benzylic organometallic species; non-anionic nucleophiles such as isopropanol can also be added in the presence of exogenous base (Scheme 11). For N-TBS, B-alkyl- or aryl-substituted 1,2-azaborines, the N-TBS group can subsequently be removed with TBAF (vide infra, Scheme 16).

Scheme 11.

Nucleophilic substitution of N-TBS-B-Cl 1,2-azaborine.

Scheme 16.

Removal of the N-TBS protecting group of 1,2-azaborine.

Nucleophilic addition at the boron position is also possible with sterically more hindered C3-substituted N-TBS-B-Cl-1,2-azaborines (Scheme 12). C3-Vinyl substituted 1,2-azaborines 28g and 28h were converted to BN-analogues of indenyl anion and naphthalene, respectively.7 In the case of C3-brominated substrate 4,20 it appears that addition to boron with organolithium reagents occurs more rapidly than lithium–halogen exchange at the C3–Br position.

Scheme 12.

Nucleophilic addition to sterically hindered C3-substituted N-TBS-B-Cl-1,2-azaborines.

Ashe has reported additional transformations of C3-halide substituted 1,2-azaborine beyond cross-coupling chemistry.5 For example, C3-brominated 1,2-azaborine 2 is converted to cyano-substituted 29a with CuCN at elevated temperature (Scheme 13a).5 Reportedly the synthesis of a 1,2-azaborine-phenol 29b has been accomplished presumably via a C3-iodinated 1,2-azaborine intermediate (Scheme 13b).‡

Scheme 13.

Nucleophilic substitutions at C3 position of azaborine.

Electrophilic substitution at nitrogen

The pKa of the azaborine N–H bond is approximately 24, much more acidic than the other C–H positions on the ring, which have pKa’s between 43 and 47.10 Ashe demonstrated that strong amide bases such as LDA21 or KHMDS22 can generate amide 30a from N-H substituted 14d in high yield (Scheme 14a). Compound 30a can be isolated as a solid and then reacted with various electrophiles such as MeI21 or TMSCl22 to afford 20f and 20g, respectively. Complexes of 1,2-azaborine with transition metals (e.g., Ru(II)21 or Zr(IV)22) can also be synthesized from 30a. Liu demonstrated that deprotonation of 1,2-azaborine 14b followed by quenching with di-tert-butyldicarbonate furnishes the N-Boc protected 1,2-azaborine 20h (Scheme 14b).17 Liu also demonstrated that epoxides can serve as suitable electrophiles for 1,2-azaborine anions such as 30b to produce β-amino alcohols 33 (Scheme 15).20

Scheme 14.

(a) Generation of amide 30a and N-substitution with electrophiles. (b) Boc protection of the N-position of the 1,2-azaborine.

Scheme 15.

Reaction between 1,2-azaborine amide 30b and epoxides.

An alternative method for generating amides such as 30a or 30b is to treat an N-silyl protected 1,2-azaborine with TBAF; the intermediate amide can then be quenched for example with a proton to afford the corresponding N-H-1,2-azaborine. Examples include N-TMS21 and N-TBS-substituted 1,2-azaborines (Scheme 16).10,16,20,23,24

B–X activation

In addition to the direct displacement of a suitable leaving-group (e.g., H, Cl, OR) at the boron position with a nucleophile via an addition/elimination process, a boron substituent can be installed by transition-metal catalyzed B-X activation chemistry. This section summarizes methods for functional group interconversions at the boron position mediated by rhodium and copper complexes.

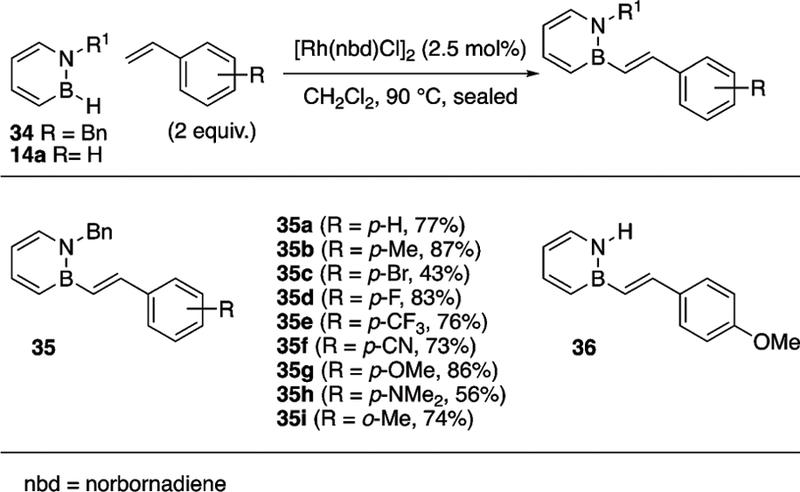

In 2013, the Liu group described a Rh-catalyzed arylation of B–Cl substituted 1,2-azaborines 21 and 3 with arylstannanes (Scheme 17).24 Mechanistic studies reveal that the reaction proceeds by a series of transmetalations, first between the Rh catalyst and the arylstannane followed by the transfer of the aryl group from Rh to the 1,2-azaborine. A wide variety of arylstannanes are tolerated including those containing esters, aldehydes, ketones, and arylstannanes bearing electron-withdrawing, and electron-donating groups. The BN-analogue of felbinac, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, was prepared with the key bond-forming step being the arylation of 3 to afford 27k followed by global deprotection with TBAF to yield BN felbinac 14u (see Scheme 16 for its structure). In addition to Rh-catalyzed B–Cl arylation, the Liu group also demonstrated B–H activation with a Rh-catalyst.25 While the relatively non-hydridic B–H bond does not participate in hydroboration in the absence of promoters, a Rh-catalyst can effect the dehydrogenative borylation of styrenes (Scheme 18). A variety of BN-stilbenes have been prepared with this method, including the BN-analogue 36 of the biologically active 4-methoxy-trans-stilbene. Only the trans-BN stilbenes were isolated under the reaction conditions among possible products (e.g., cis-stilbene or hydroboration products). A potential mechanism may involve an oxidative addition of the B–H bond to Rh followed by β-migratory insertion of the Rh–B bond into the styrene substrate. Subsequent β-hydride elimination would produce the desired trans BN stilbene product and a Rh dihydride complex which hydrogenates a second styrene substrate to restart the catalytic cycle.25

Scheme 17.

Rh-Catalyzed arylation of B-Cl 1,2-azaborines.

Scheme 18.

Rh-catalyzed B–H activation of 1,2-azaborines.

As previously shown, B-alkoxide groups of 1,2-azaborines are readily modifiable by nucleophilic substitution chemistry, however, they often are incompatible with other late-stage transformations. On the other hand, carbon-based boron groups, particularly arenes, provide chemical robustness to the 1,2-azaborines and prevent side-reactions. In 2017, the Liu group reported a reaction that exchanges B-alkyl or B-aryl moieties for a B-alkoxide fragment (Scheme 19).20 This formal oxidation process allows carbon-based groups to function as a protecting group for the boron position that can be later transformed to the easily modifiable alkoxide moiety. Thus, under the optimized conditions, a Cu(I) compound mediates the homolytic cleavage of the B–C bond in the presence of a stoichiometric oxidant. Functional groups at the C6-, N-, and C3-positions are tolerated, including the N-TBS and the free N-H group. B-Alkyl, in particular B-benzyl substituted 1,2-azaborines are good substrates. B-Phenyl groups, as in 27b, 14d, 27g, and 27h are removed in modest yield, possibly due to decreased stability of the putative sp2-based phenyl radical. Notably, a C3–Br substituted 1,2-azaborine is a suitable substrate for the reaction, albeit with modest yield (Scheme 19, entry 11).

Scheme 19.

Cu-Catalyzed B–R oxidation of 1,2-azaborines.

An intramolecular version of the B-alkyl to B-alkoxide exchange reaction was also demonstrated. B-Benzyl-substituted 1,2-azaborines 33, accessed via ring-opening reaction of 1,2-azaborine anions with epoxides (Scheme 15), engage in the intramolecular displacement of B-alkyl groups to afford BN-dihydrobenzofurans 38 (Scheme 20).20

Scheme 20.

Intramolecular Cu-catalyzed B-R activation and oxidation of 1,2-azaborines to form BN-dihydrobezofuran isosteres.

BN-styrene reactivity

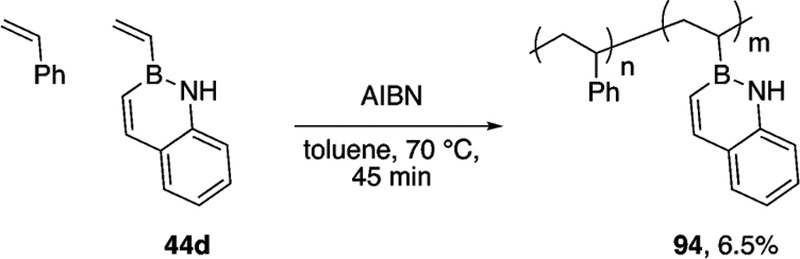

Like their all-carbon counterparts, BN-styrenes polymerize in the presence of free-radical initiators and also undergo controlled RAFT polymerization. Jäkle and Liu established that high molecular weight, atactic polymers can be obtained from the polymerization of monomer 14m; the lower reactivity and yield compared to styrene was attributed to the decreased stability of the benzylic radical that is formed adjacent to boron during the polymerization process (Scheme 21).23 The polymerization of the BN-analogue of para-vinylbiphenyl 14t was also reported; yields comparable to the all-carbon analogue were observed. Staubitz reported the polymerization of N-Me monomer 5a but obtained higher molecular weights and slightly improved reactivity compared to N-H monomer 14m.16 The Staubitz group was also able to copolymerize 5a with 2-vinyl-toluene. The resulting copolymer had a composition of approx. 3 : 2 (BN : CC) and its NMR characterization suggests a relatively random monomer distribution. The random nature of the copolymer as well as reaction progress monitoring by NMR suggest the rates of polymerization of the two monomers amongst themselves and with one another must be in the same order of magnitude. In another example of BN-styrene late-stage functionalization, the Liu group performed hydrogenation of the vinyl group in compound 16g (Scheme 22).20

Scheme 21.

Free-radical polymerization of B-vinyl-1,2-azaborines.

Scheme 22.

Hydrogenation of C6-vinyl azaborine.

Diels–Alder

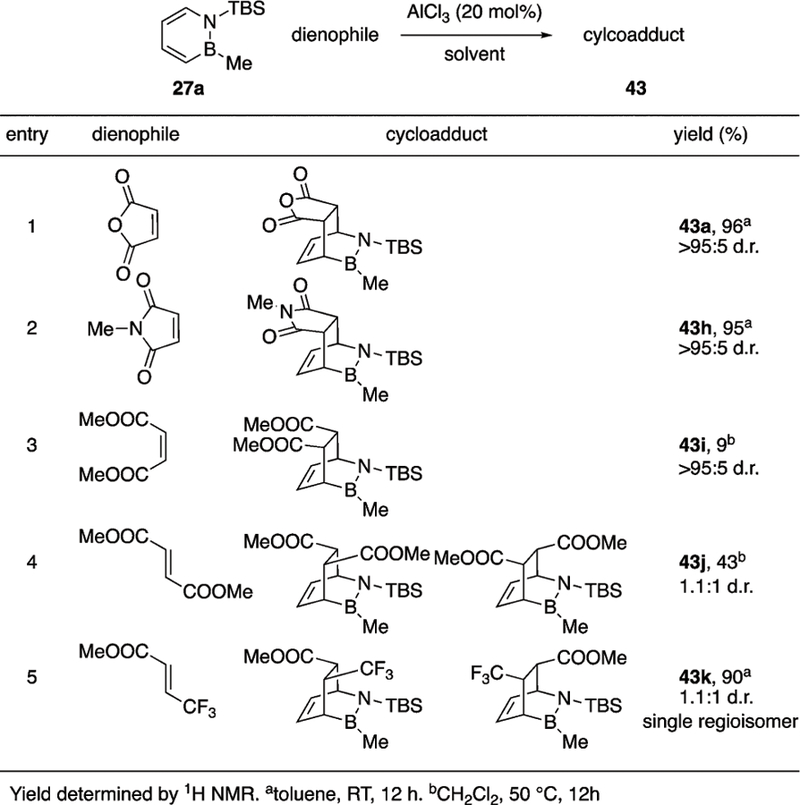

While benzene does not typically engage in Diels–Alder reactions, it was found that 1,2-azaborine undergoes [4+2] cycloaddition with activated dienophiles.17 With a resonance stabilization energy (RSE) of about 32 kcal mol−1, benzene lacks sufficient thermodynamic driving force to break its aromaticity and engage in a thermal cycloaddition. On the other hand, parent azaborine 14a has an RSE of about 19 kcal mol−1 which situates it between two heterocycles known to engage in cycloaddition reactions, pyrrole (21 kcal mol−1) and furan (15 kcal mol−1). 1,2-Azaborines react smoothly with maleic anhydride in the presence of a catalytic amount of AlCl3 to afford the corresponding endo-cycloadducts; however, the reaction is highly sensitive to the nature of the boron and nitrogen substituents of the 1,2-azaborine (Scheme 23). High yields were obtained with the TBS group on nitrogen and Me or O-iPr on boron. Yields fell precipitously when R1 was changed to Boc or when R2 was changed to H or alkyne. B-H and B-alkynyl 1,2-azaborines display increased measures of aromaticity (e.g., by NICS and RSE calculations) relative to B-alkyl or B-alkoxy 1,2-azaborines. Increased aromaticity corresponds to reduced Diels–Alder reaction free energy of the former compounds relative to the latter.17

Scheme 23.

Diels–Alder reaction of 1,2-disubstituted-1,2-azaborines.

The scope of dienophiles was limited to highly activated substrates (Scheme 24). Reactions between 1,2-azaborine and less-activated dienophiles (Scheme 24, entries 3 and 4) never went to completion, regardless of the conditions. High diastereoselectivities were observed with cis-alkenes but selectivity was eroded with trans-alkenes. Reaction with the unsymmetrical alkene in entry 5 led to a single regioisomer, consistent with the more nucleophilic nature of the C3 and more electrophilic nature of the C6 positions, respectively.

Scheme 24.

Diels–Alder reaction of azaborine 27a with activated dienophiles.

BN-naphthalenes

EAS

Some of the reactions described for 1,2-azaborines have also been optimized for BN-naphthalenes: primarily the 1,2 and 9,10 isomers and to a lesser extent the 2,1 isomer. For the purpose of this review, the prefix numbers refer to the positions of the nitrogen (first number), and boron (second number) with respect to the labelling convention of the corresponding hydrocarbon motif. Dewar pioneered the synthesis of 1,2- and 9,10-BN-naphthalenes and their “late-stage” functionalization. Molander and Fang later improved these methods for the 1,2-BN-naphthalene and 9,10-BN-naphthalene, respectively. Similar to their monocyclic counterparts, BN-naphthalenes are attacked by electrophiles at the most electron-rich position which is typically the carbon adjacent to boron atom.

In the case of 1,2-BN-naphthalene, Molander investigated its EAS chemistry, improving reaction yields and greatly increasing the substrate scope beyond the initial work by Dewar (Scheme 25a).26 Alkyl and H substituents are tolerated at nitrogen and alkyl, aryl, heteroaryl, and alkenyl substituents are tolerated at boron. Doubling the equivalents of bromine led to secondary bromination at the C6 position (Scheme 25b). Bromination at C6 also occurs when the C3 position is already substituted (Scheme 25c).

Scheme 25.

(a) Bromination of 1,2-BN-naphthalene. (b) Dibromination of 1,2-BN-naphthalene. (c) Bromination of C3-substituted 1,2-BN-naphthalene.

The most nucleophilic positions of the 9,10-BN-naphthalene are the C4 and C5 carbon positions adjacent to boron. Fang developed a halogenation procedure for 9,10-BN-naphthalene using N-halosuccinimides promoted by AlCl3 (Scheme 26).27 Repeating the process with the same or a different halogenating reagent installs a second halide at the C5 position. Acylation of 9,10-BN-naphthalene has also been demonstrated by Fang. Acylation of the C4 position with acyl chlorides proceeds in good to excellent yield with either AlCl3 or AgBF4 as the Lewis-acid promoter (Scheme 27).9 Aroyl and alkanoyl chlorides were effective substrates in the acylation reaction and all furnished C4 BN-naphthyl ketones. Dimethylcarbamoyl chloride was the exception, which yielded the C2 isomer 54p. Repeating the acylation procedure with acetylated 54a produced bisacetylated compound 54aa (Scheme 28a). A BN-phenalenone adduct was accessible via a tandem acylation, cyclization of 52 with methacryloyl chloride (Scheme 28b). Fang and coworkers also extended their nitration to 9,10-BN-naphthalene, which installs a nitro group at C2 position (Scheme 28c).8

Scheme 26.

Mono and dihalogenation of 9,10-BN-naphthalene.

Scheme 27.

Acylation of 9,10-BN-naphthalene.

Scheme 28.

(a) Acylation of BN-aryl ketone 54a. (b) BN-phenalenone 55 prepared via-acylation–cyclization procedure. (c) Nitration of BN-naphthalene 52.

In 2018, Vaquero reported a complementary approach to the acylation reaction described by Fang and demonstrated the installation of an acyl group at the C1 position of 9,10-BN-naphthalene (Scheme 29).28 Treating 52 with a strong base such as t-BuLi leads to deprotonation of the most acidic C1-proton (Scheme 29a). Subsequent treatment of the C1-lithiated BN heterocycle with aldehydes furnishes alcohols 57 in good yield. The Vaquero group then discovered that the use of the more nucleophilic n-BuLi (vs. t-BuLi) can activate the C2 and C7 positions of 9,10-BN-naphthalene for EAS reactions with aldehydes (Scheme 29b). While C1-deprotonation still occurs with n-BuLi to form 57a, the authors also observed the formation of C2- and C7-difunctionalized EAS product 58 in modest yield. n-BuLi activates compound 52 to EAS via initial addition to the boron atom to form a borate. Then the nitrogen lone pair participates in enamine-like reactivity, leading to EAS β to the nitrogen. It is worth noting that one of the benzylic hydroxy groups has been replaced with an n-butyl group.

Scheme 29.

(a) C1 acylation of 9,10-BN-naphthalene. (b) C2, C7 difunctionalization of 9,10-BN-naphthalene via activation with n-BuLi.

Borylation

The previous section covered methods for preparing halogenated 1,2-BN-naphthalenes as electrophilic building blocks. This section will describe the synthesis of nucleophilic BN naphthalene building blocks. Molander demonstrated that brominated 1,2-BN-naphthalenes 46 can undergo Miyaura borylation at the C3 position (Scheme 30a).29 C3-Borylated 59 can subsequently be converted to BF3K salts 60 in good yields (Scheme 30b). Both boron reagents 59 and 60 are suitable substrates for Suzuki cross-coupling reactions (vide infra). Along with Miyaura borylation, Molander also described the selective C–H borylation of 1,2-BN-naphthalenes at the C8 position (Scheme 31a).30 Alkyl and aryl substituents at B (R2), aryl and bromo substituents at C3 (R3), and alkyl, CF3, CN, and ether substituents at C6 (R6) are all tolerated. Anything larger than a proton on N or a proton or fluorine on C7 (R7) would sterically preclude borylation at the C8 position. The first C–H borylation is generally selective for the C8 position. A second Bpin can also be selectively installed at the C6 position to yield 62 in the presence of excess B2pin2 with elevated temperatures (Scheme 31b). When the C8 position is sterically blocked, as in N-Me substituted 45a, standard C–H borylation conditions lead to a mixture of C7 and C6 borylated isomers in a 70 : 30 ratio favoring the C7 isomer (Scheme 31c).

Scheme 30.

(a) Miyaura borylation of 3-bromo-1,2-BN-naphthalenes. (b) Conversion of 3-Bpin-1,2-BN-naphthalenes to corresponding BF3K salts.

Scheme 31.

(a) C–H borylation at C8 position of N-H-1,2-BN-naphthalene. (b) Bisborylation at C8 and C6 positions of 1,2-BN-naphthalene. (c) Mono-borylation at C7 and C6 positions of N-substituted 1,2-BN-naphthalene.

Cross-coupling

Molander, Fang, and Pei have all contributed to the cross-coupling chemistry of BN-naphthalenes. Molander has published extensively on the cross-coupling of 1,2-BN-naphthalenes, detailing a number of methods for functionalizing the C3, C6, and C8 positions totalling in the hundreds of substrates. Pei has demonstrated cross coupling at the C4 position of 1,2-BN-naphthalene, while Fang reported cross-coupling methods for the 9,10 isomer of BN naphthalene.

C3 brominated 1,2-BN-naphthalenes 46 and 47 engage in Suzuki cross-coupling with aryl BF3K salts in modest to excellent yields (Scheme 32a).26 Changing the catalyst and solvent broadened the scope of BF3K coupling partners to include alkenyl substrates (Scheme 32b).31 N-Alkyl, B-aryl substituted 47 serves as the electrophilic partner in the Kumada coupling of aryl Grignard reagents (Scheme 32c).32

Scheme 32.

Suzuki cross-coupling of 3-bromo-1,2-BN-naphthalenes and (a) aryl BF3K reagents; (b) alkenyl BF3K reagents. (c) Kumada cross-coupling of 3-bromo-1,2-naphthalenes and aryl Grignard reagents.

In order to extend the scope of cross-coupling reactions of 1,2-BN-naphthalenes to include alkyl reagents, Molander et al. developed the reductive cross-coupling of BN heteroaryl bromides and alkyl iodides.33 Optimal conditions for the reductive cross-coupling include a Ni-catalyst supported by a bipyridine ligand, 4-ethylpyridine and NaBF4 as additives, and Mn as the reductant (Scheme 33a). Cross-coupling of various alkyl iodides proceeds in modest to excellent yield. Molander et al. subsequently expanded the scope of alkyl coupling partners to include more sensitive functional groups, especially those susceptible to reduction, by developing a photoredox/nickel dual catalytic functionalization.34 The base-free method for derivatizing BN-naphthalene with ammonium bis(catecholato)silicates occurs at room temperature and is promoted by a Ni-catalyst and a Ru-derived photocatalyst (Scheme 33b). Functional groups such as esters, amides, lactams and even free amines are tolerated for the reaction.

Scheme 33.

(a) Reductive cross-coupling of 3-bromo-1,2-BN-naphthalenes and alkyl iodides. (b) Photoredox/nickel dual-catalytic functionalization of 3-bromo-1,2-BN-naphthalenes.

Borylated BN-naphthalenes serve as the nucleophilic partner in a cross-coupling reaction. C3-Boron pinacol ester 59a (Scheme 34a) and C3-BF3K salt 60d (Scheme 34b) readily undergo Suzuki cross-coupling reactions.29

Scheme 34.

(a) Cross-coupling of C3-Bpin-1,2-BN-naphthalene. (b) Cross-coupling of C3-BF3K-1,2-BN-naphthalene.

Molander et al. also developed a method for C3 functionalization via Suzuki cross-coupling where the BN-naphthalene contains both the nucleophile and the electrophile.32 This self-arylation occurs when a B-aryl, C3-bromo 1,2-BN-naphthalene is treated with a palladium catalyst and strong base; the B-aryl group undergoes a net migration to the C3 position (Scheme 35).

Scheme 35.

Self-arylation of 1,2-BN-naphthalenes.

A crossover experiment revealed that the self-arylation is an intermolecular process. The boron atom of the 1,2-BN-naphthalene is hydrolyzed during the self-arylation, and the reaction affords a mixture of anhydride 71 and alcohol 72. Treating the anhydride with KOH in THF/H2O converts it to the hydroxy compound.

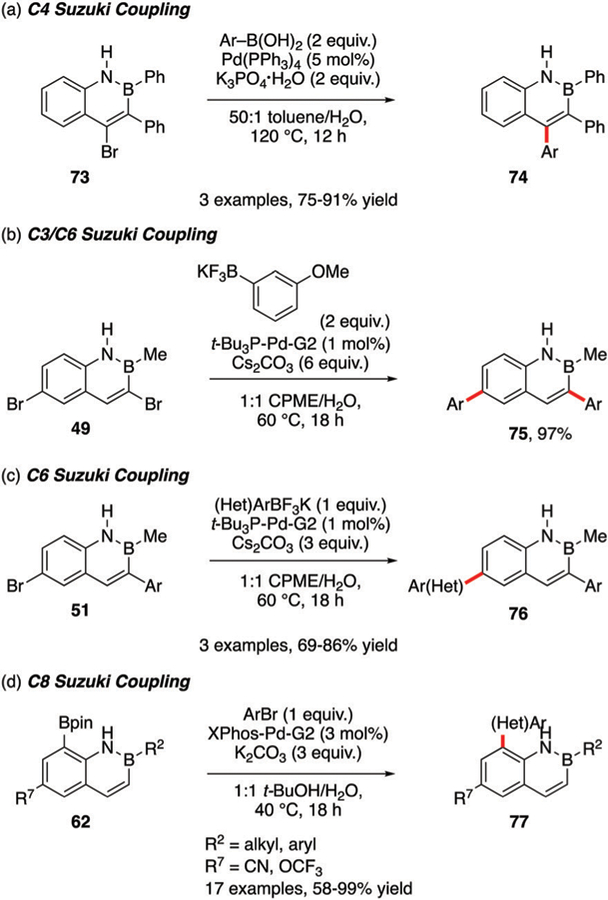

Suzuki cross-coupling has been deployed as a functionalization method for other positions on the 1,2-BN-naphthalene ring, including the C4, C6, and C8 positions. Using a bottom-up synthesis, Pei incorporated a bromine atom at the C4 position that serves as a handle for cross-coupling to afford a triaryl substituted BN-naphthalene core 74 (Scheme 36a).35 Cross-coupling of bisbrominated 49 or mono-C6-brominated 51 with aryl-BF3K reagents affords the corresponding C3,C6 substituted naphthalenes (Scheme 36b and c).26 The reactions depicted in Scheme 36b and c can also be performed with alkenyl-BF3K reagents (cf. Scheme 32b).31 The reductive cross-coupling method depicted in Scheme 33a has also been applied to compound 51.33 Suzuki coupling is also effective with C8-Bpin 62 and a variety of aryl bromides (Scheme 36d).30

Scheme 36.

(a) Suzuki coupling at the C4 position of 1,2-BN-naphthalene; (b) C3 and C6 positions; (c) C6 position; (d) C8 position.

Fang described cross-coupling methods to functionalize 9,10-BN-naphthalenes, including Suzuki coupling (Scheme 37a), Sonogashira coupling (Scheme 37b), and Heck reaction (Scheme 37c).27 Several examples of arylboronic acids, alkynes as well as one example of an alkene engage in coupling with the C4-iodo compound 53i. Diaryl phosphines also function as nucleophiles in a coupling reaction with 53i to form BN-containing phosphine ligand 81 (Scheme 37d).36

Scheme 37.

(a) Suzuki coupling of 9,10-BN-naphthalene; (b) Sonogashira coupling; (c) Heck reaction; (d) C–P coupling.

Nucleophilic substitution

Dewar first reported the synthesis and functionalization of the 1,2-BN-naphthalene in 1959.37 Incorporating a B–Cl bond into the synthesis allowed for ready functionalization of the product at the boron position via nucleophilic substitution, albeit in modest yields. An excess amount of hydride or methyl or phenyl Grignard reagents displace the chloride in N-H, B-Cl 1,2-BN-naphthalene 82 to afford substituted 44 after aqueous workup (Scheme 38a). In 2014, Molander showed that the B–OH bond-containing compound 72a, the product of the self-arylation reaction, could be substituted with a phenyl group with a Grignard reagent (Scheme 38b).32 In 2015, Cui reported the first synthesis and late-stage functionalization of the 2,1-BN-naphthalene.38 The incorporation of the B–Br bond in compound 83 allows for the relatively facile substitution with various nucleophiles to afford compound 84 (Scheme 38c).

Scheme 38.

(a) Nucleophilic substitution at the boron position of 1,2-BN-naphthalene by Dewar. (b) Nucleophilic substitution at the boron position of 1,2-BN-naphthalene by Molander. (c) Nucleophilic substitution at the boron position of 2,1-BN-naphthalene by Cui.

Benzylic functionalization

In 2014 Molander et al. prepared 2-chloromethyl-1,2-BN-naphthalene, a building block for benzylic functionalization.39 Like its benzylic halide counterpart, the BN compound 85 undergoes nucleophilic substitutions with a wide variety of nucleophiles including amines, alcohols, carboxylic acids, thiols, and azide (Scheme 39). Cross-coupling reactions including Suzuki and Sonogashira reactions have also been reported.40 Borylation and subsequent use of benzylic BF3K reagent 93 as the nucleophile in cross-coupling reactions is also possible.41

Scheme 39.

Benzylic functionalizations of 1,2-BN-naphthalene.

Similar to the BN-styrenes 14m and 5a (vide supra, Scheme 21), Klausen demonstrated that B-vinyl, 1,2-BN-naphthalene 44d displays styrene-like reactivity (Scheme 40).42 The reactivity of styrene and monomer 44d are similar enough to prepare statistical copolymers using free-radical polymerization promoted by AIBN.

Scheme 40.

Copolymerization of styrene and 1,2-BN-naphthalene 44d.

Electrophilic substitution at nitrogen

In an effort to prepare boron-containing organic compounds for neutron capture therapy Dewar reported a procedure for the substitution of 1,2-BN-naphthalene at the nitrogen position with various electrophiles.43 N-H-B-Me-1,2-BN-naphthalene 44a is first deprotonated with MeLi and then quenched with an alkyl or alkanoyl electrophile (Scheme 41). N-Me, allyl, and ethyl-ester substituted 1,2-BN-naphthalenes 45 were prepared in good yield.

Scheme 41.

Electrophilic substitution at the nitrogen position of 1,2-BN-naphthalene.

BN-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (BN-PAHs)

The chemistry of BN-doped polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons encompasses a vast body of literature. The reader is encouraged to read the reviews by Piers1 and Liu2 and references therein as a starting point for this literature. Compared to the large number of publications about the assembly of BN-PAHs there are relatively few examples of late-stage functionalizations of these heterocycles. This section details the available methods for the late-stage functionalization of the 9,10- and 4a,10a-BN-phenanthrenes, 1,2- and 9a,9-BN-anthracenes, and a BN-tetraphene.

EAS

As an early example of an EAS reaction of a BN heterocycle, Dewar in 1959 reported that EAS occurs at the C8 position of 9,10-BN-phenanthrene (Scheme 42).44 Treatment of 9,10-BN-phenanthrene 95a with chlorine or nitric acid affords the respective EAS product in moderate yield. 9,10-BN-phenanthrene is a remarkably stable compound, given the relatively harsh conditions of these substitution reactions by current standards.

Scheme 42.

EAS reactions of 9,10-BN-phenanthrene.

Vaquero synthesized the 4a,10a-BN-phenanthrene 97, and like its simpler analogue 9,10-BN-naphthalene, it is attacked by halogen electrophiles at the carbon position adjacent to boron (Scheme 43a).45 Either a Cl or a Br can be installed in good to excellent yield.

Scheme 43.

EAS reactions of 4a,10a-BN-phenanthrene.

When propanal is used as the electrophile, it can be attacked by two equivalents of 97 to form 99 (Scheme 43b). Selectivity for the EAS reaction with aldehydes can be shifted to the carbon position β to the nitrogen atom by employing n-BuLi as an activator (Scheme 43c). The activation method is analogous to the one described in Scheme 29 for 9,10-BN-naphthalene. Aldehyde and ketone electrophiles are viable substrates for EAS and unlike 9,10-BN-naphthalene the reaction is completely regioselective. The resulting carbinol reacts with an additional equivalent of the alkyllithium reagent, furnishing alkylated 100 in moderate to excellent yields.

Liu et al. reported the first example of a BN-anthracene in 2014.46 Unlike its bi- and monocyclic analogues, EAS of the 1,2-BN-anthracene does not occur at the C3 position adjacent to B but rather at the C9 position (Scheme 44a). The authors found that there is a significant contribution to the HOMO from C9 but a vanishingly small one from C3. Thus, the reaction appears to be orbitally controlled which is consistent with the “soft” nature of the Br2 electrophile. In 2019, the Liu group reported another anthracene isomer, the 9a,9 isomer.47 Substitution of 103 with bromine was selective for the apical C10 position (Scheme 44b). Cui prepared BN-tetraphene 105 and also demonstrated EAS with bromine, yielding functionalized 106 (Scheme 45).48

Scheme 44.

(a) Bromination of 1,2-BN-anthracene. (b) Bromination of 9a,9-BN-anthracene.

Scheme 45.

Bromination of BN-tetraphene.

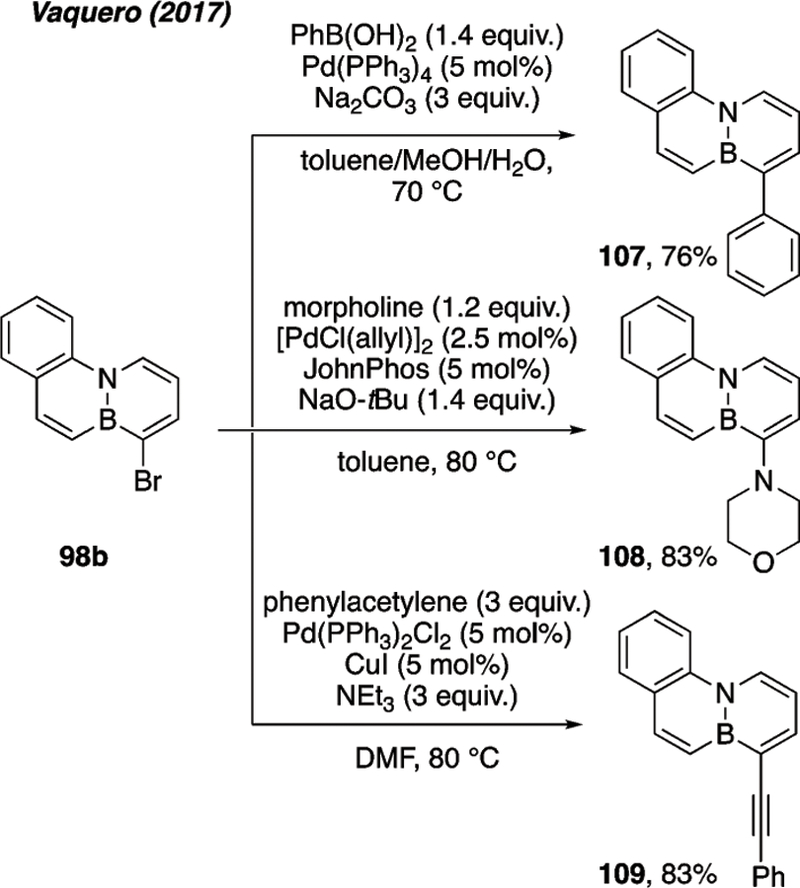

Cross-coupling

Brominated 98b serves as the electrophile in three different cross coupling reactions.45 Suzuki cross-coupling leads to arylated 107, Buchwald–Hartwig coupling furnishes amine-substituted 108, and Sonogashira coupling installs an alkyne in product 109 (Scheme 46). The brominated BN-anthracenes 102b and 104 also undergo Suzuki cross-coupling with aryl-boronic acids to furnish 110 (Scheme 47a)46 and 111 (Scheme 47b), respectively.47 Cui reported an example of Sonogashira coupling to functionalize brominated BN-tetraphene 106 (Scheme 48).48

Scheme 46.

Cross-coupling reactions of brominated BN-phenanthrene 98b.

Scheme 47.

(a) Cross-coupling at C9 position of 1,2-BN-anthracene. (b) Cross-coupling at C10 position of 9a,9-BN-anthracene.

Scheme 48.

Cross-coupling of BN-tetraphene.

Nucleophilic substitution

Synthesis of B–Cl substituted 113 provides a functional handle for nucleophilic substitution at the boron position. Dewar reported four examples of nucleophiles that displace the B–Cl: water, methyl Grignard, ethyl Grignard, and phenyl Grignard (Scheme 49).49

Scheme 49.

Nucleophilic substitution of 9,10-BN-phenanthrene 113.

Electrophilic substitution

Similar to the analogous 1,2-BN-naphthalene, a strong base will deprotonate the N–H proton of BN-phenanthrene 95a (Scheme 50).43 The resulting amide was substituted with allylbromide in good yield.

Scheme 50.

Electrophilic substitution at N of 9,10-BN-phenanthrene.

B–X activation

In an effort to synthesize BN-arene containing phosphine ligands, Pringle et al. discovered that B-Cl substituted BN-phenanthrene 113 reacts with silylphosphines at room temperature to afford BN-phosphine ligands 115 (Scheme 51).50 The ease with which the B–Cl bond reacts with the P–Si bond was somewhat surprising given that formation of a P–B bond from Et2PSiMe3 and ClB(n-Pr)2 required several hours at high temperatures (120 °C).

Scheme 51.

Exchange reaction between B–Cl 113 and silylphosphines.

Distinct reactivity of BN-heterocycles

Replacing a CC with a BN unit of an arene can render each position of the resulting BN-heterocycle electronically distinct. As a result, the BN bond imbues distinct selectivity to a BN-heterocycle as compared to analogous reactions of its all-carbon counterpart. Based on the results presented in this review, several selectivity trends emerge for certain reactions of BN-heterocycles.

For monocyclic 1,2-azaborines and BN-naphthalenes, EAS occurs at the position adjacent to boron which is the most electron-rich (Schemes 1, 25, 26 and 43). Friedel–Crafts reactions can occur either adjacent to boron (Schemes 27 and 43), or at the second-most electron-rich position β to nitrogen (Schemes 2, 3, 27–29 and 43) depending on the conditions. EAS selectivity for BN-PAHs does not necessarily follow these trends.

The N–H bond is the most acidic position and thus can be selectively deprotonated and functionalized with electrophiles (Schemes 14, 15 and 41). The closest C–H proton to the nitrogen atom is the most acidic proton and will selectively engage in deprotonation/functionalization (in the absence of an N–H proton) (Scheme 29) or C–H borylation (Schemes 4 and 31).

The boron atom is the most electrophilic position of a BN-heterocycle due to its partially occupied p-orbital. If a leaving group is attached, it will undergo substitution preferentially in the presence of other carbon-based leaving-groups (Scheme 12).

More broadly, the presence of the boron atom provides the opportunity to perform reactions not available to all-carbon compounds. Activation of various B–X bonds is possible: B–Cl bonds undergo transmetalations (Schemes 17 and 51); B–H bonds can undergo dehydrogenative borylation (Scheme 18); B–C bonds can undergo oxidation (Schemes 19 and 20) as well as the unique self-arylation reaction (Scheme 35); boron atoms internal to BN-PAHs can be activated with n-butyllithium, which in turn activates specific positions to functionalizations (Schemes 29 and 43). Finally, monocyclic 1,2-azaborines undergo Diels–Alder reactions under thermal conditions unlike their benzene-derived counterparts (Schemes 23 and 24).

Concluding remarks

Significant progress has been made in the field of azaborine chemistry in the past two decades. The synthetic access to a continuously growing library of BN heterocyclic compounds has led to the discovery of new properties and functions in a variety of disciplines ranging from biomedical research to materials science. Despite the advances made to date, the field is still in relatively early stages of development and remains limited by the synthetic access to new BN heterocycles and their derivatives. The literature surveyed in this review highlights the distinguishing reactivity/selectivity patterns exhibited by BN heterocycles relative to their carbonaceous counterparts. It is also clear from the survey that the available synthetic toolbox for derivatizing BN heterocycles falls far short of the capabilities developed for arenes. Thus, further development in this area will undoubtedly help mature this burgeoning field. Overall, BN/CC isosterism as a general approach to create new function has tremendous potential due to the near unlimited chemical space provided by hydrocarbon compounds. Exciting untapped opportunities related to reaction chemistry that take advantage of the distinct electronic structure of BN heterocycles include new bioconjugation chemistry and the use of BN heterocycles as synthons in organic synthesis, to name a few.

Key learning points.

This review provides an overview of late-stage functionalization methods for monocyclic as well as polycyclic 1,2-azaborine heterocycles.

This review highlights the distinct reactivity and reaction selectivity of BN-heterocycles relative to their all-carbon counterparts.

This review includes all of the recent examples of late-stage functionalization published within the last decade.

This review presents “building block” strategies that have been used to diversify the functional groups available to BN-heterocycles.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the many co-workers in the Liu laboratory who have contributed to the results described in portions of this review. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health NIGMS (R01-GM094541) and National Science Foundation (CHE-1561153).

Biography

Cameron R. McConnell was born in Baltimore, MD, in 1991, and he grew up in Allentown, PA. He received his BS degree in Chemistry from Bucknell University in 2013. He is scheduled to complete his PhD degree under the direction of Professor Shih-Yuan Liu at Boston College in 2019 investigating late-stage functionalization methods of the monocyclic 1,2-azaborine heterocycle and the incorporation of 1,2-azaborines in BN-containing conjugated materials.

Shih-Yuan Liu received his BS degree in Chemistry from Vienna University of Technology in 1998. He did his doctoral work at MIT with Prof. Gregory C. Fu and received his PhD degree in organic chemistry in 2003. He then pursued his postdoctoral studies in inorganic chemistry with Prof. Daniel G. Nocera, also at MIT. He started his independent career at the University of Oregon in 2006, and he was promoted to Associate Professor in 2012. He joined Boston College as a Full Professor in 2013. His research interests include the development of boron–nitrogen heterocycles for materials and biomedical applications.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Compound 3 is now commercially available from www.strem.com, catalog number 05–0150. Accessed on 3/23/2019.

Intriguingly, the 11B NMR shift of compound 29b (28 ppm) typically indicates the presence of a B–O bond.

Notes and references

- 1.For an overview of BN/CC isosterism in aromatic compounds, see: Bosdet MJD and Piers WE, Can. J. Chem, 2009, 87, 8–29. [Google Scholar]

- 2.For a history of azaborine chemistry, see: Campbell PG, Marwitz AJV and Liu S-Y, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2012, 51, 6074–6092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For recent developments in azaborine chemistry, see: Bélanger-Chabot G, Braunschweig H and Roy DK, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem, 2017, (38–39), 4353–4368. [Google Scholar]

- 4.For a perspective on the applications of azaborines, see: Giustra ZX and Liu S-Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2018, 140, 1184–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan J, Kampf JW and Ashe AJ, Org. Lett, 2007, 9, 679–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chrostowska A, Xu S, Lamm AN, Maziére A, Weber CD, Dargelos A, Baylére P, Graciaa A and Liu S-Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2012, 134, 10279–10285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown AN, Li B and Liu S-Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2015, 137, 8932–8935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Dan W and Fang X, Organometallics, 2017, 36, 1677–1680. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Sun F, Dan W and Fang X, J. Org. Chem, 2017, 82, 12877–12887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baggett AW, Vasiliu M, Li B, Dixon DA and Liu S-Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2015, 137, 5536–5541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baggett AW, Guo F, Li B, Liu S-Y and Jäkle F, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2015, 54, 11191–11195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terrier F, Modern Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution, Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, 1st edn, 2013, ch. 1, pp. 1–94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamm AN, Garner EB, Dixon DA and Liu S-Y, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2011, 50, 8157–8160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbey ER, Lamm AN, Baggett AW, Zakharov LN and Liu S-Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2013, 135, 12908–12913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marwitz AJV, Abbey ER, Jenkins JT, Zakharov LN and Liu S-Y, Org. Lett, 2007, 9, 4905–4908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thiedemann B, Gliese PJ, Hoffmann J, Lawrence PG, Sönnichsen FD and Staubitz A, Chem. Commun, 2017, 53, 7258–7261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burford RJ, Li B, Vasiliu M, Dixon DA and Liu S-Y, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2015, 54, 7823–7827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McConnell CR, Campbell PG, Fristoe CF, Memmel PM, Zakharov LN, Li B, Darrigan C, Chrostowska A and Liu S-Y, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem, 2017, 2207–2210.

- 19.Marwitz AJV, Jenkins JT, Zakharov LN and Liu S-Y, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2010, 49, 7444–7447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baggett AW and Liu S-Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2017, 139, 15259–15264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan J, Kampf JW and Ashe AJ, Organometallics, 2004, 23, 5626–5629. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan J, Kampf JW and Ashe AJ, Organometallics, 2008, 27, 1345–1347. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wan W-M, Baggett AW, Cheng F, Lin H, Liu S-Y and Jäkle F, Chem. Commun, 2016, 52, 13616–13619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudebusch GE, Zakharov LN and Liu S-Y, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2013, 52, 9316–9319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown AN, Zakharov LN, Mikulas T, Dixon DA and Liu S-Y, Org. Lett, 2014, 16, 3340–3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molander GA and Wisniewski SR, J. Org. Chem, 2014, 79, 6663–6678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun F, Lu L, Huang M, Zhou Z and Fang X, Org. Lett, 2014, 16, 5024–5027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abengózar A, Fernández-González MA, Sucunza D, Frutos LM, Salgado A, García-García P and Vaquero JJ, Org. Lett, 2018, 20, 4902–4906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Compton JS, Saeednia B, Kelly CB and Molander GA, J. Org. Chem, 2018, 83, 9484–9491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies GHM, Jouffroy M, Sherafat F, Saeednia B, Howshall C and Molander GA, J. Org. Chem, 2017, 82, 8072–8084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molander GA, Wisniewski SR and Etemadi-Davan E, J. Org. Chem, 2014, 79, 11199–11204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Molander GA and Wisniewski SR, J. Org. Chem, 2014, 79, 8339–8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molander GA, Wisniewski SR and Traister KM, Org. Lett, 2014, 16, 3692–3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jouffroy M, Davies GHM and Molander GA, Org. Lett, 2016, 18, 1606–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhuang F-D, Han J-M, Tang S, Yang J-H, Chen Q-R, Wang J-Y and Pei J, Organometallics, 2017, 36, 2479–2482. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun F, Huang M, Zhou Z and Fang X, RSC Adv, 2015, 5, 75607–75611. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dewar MJS and Dietz R, J. Chem. Soc, 1959, 2728–2730. 38

- 38.Liu X, Wu P, Li J and Cui C, J. Org. Chem, 2015, 80, 3737–3744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molander GA, Wisniewski SR and Amani J, Org. Lett, 2014, 16, 5636–5639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molander GA, Amani J and Wisniewski SR, Org. Lett, 2014, 16, 6024–6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amani J and Molander GA, Org. Lett, 2015, 17, 3624–3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van de Wouw HL, Awuyah EC, Baris JI and Klausen RS, Macromolecules, 2018, 51, 6359–6368. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dewar MJS, Hashmall J and Kubba VP, J. Org. Chem, 1964, 29, 1755–1757. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dewar MJS and Kubba VP, Tetrahedron, 1959, 7, 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abengózar A, García-García P, Sucunza D, Frutos LM, Castaño O, Sampedro D, Pérez-Redondo A and Vaquero JJ, Org. Lett, 2017, 19, 3458–3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ishibashi JSA, Marshall JL, Maziére A, Lovinger GJ, Li B, Zakharov LN, Dargelos A, Graciaa A, Chrostowska A and Liu S-Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2014, 136, 15414–15421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ishibashi JSA, Darrigan C, Chrostowska A, Li B and Liu S-Y, Dalton Trans, 2019, 48, 2807–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang H, Pan Z and Cui C, Chem. Commun, 2016, 52, 4227–4230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dewar MJS, Kubba VP and Pettit R, J. Chem. Soc, 1958, 3073–3076.

- 50.Bailey JA, Haddow MF and Pringle PG, Chem. Commun, 2014, 50, 1432–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]