Abstract

Background and Purpose

We examined the resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) of the supplementary motor area (SMA) in brain tumor patients. We compared the SMA subdivisions (pre-SMA, SMA proper, central SMA) in terms of RSFC projected from each region to the motor gyrus and language areas.

Methods

We retrospectively identified fourteen brain tumor patients who underwent task-based and resting-state fMRI, and who completed motor and language paradigms that activated the SMA proper and pre-SMA, respectively. Regions of interest (ROIs) obtained from task-based fMRI were generated in both areas and the central SMA to produce RSFC maps. Degree of RSFC was measured from each subdivision to the motor gyrus and Broca’s area (BA).

Results

All patients showed RSFC between the pre-SMA and language centers and between the SMA proper and motor gyrus. 13/14 showed RSFC from the central SMA to both motor and language areas. There was no significant difference between subdivisions in degree of RSFC to BA (pre-SMA, r=0.801; central SMA, r=0.803; SMA proper; r=0.760). The pre-SMA showed significantly less RSFC to the motor gyrus (r=0.732) compared to the central SMA (r=0.842) and SMA proper (r=0.883) (p=0.016, p=0.001, respectively).

Conclusions

The region between the pre-SMA and SMA proper produces reliable RSFC to the motor gyrus and language areas in brain tumor patients. This study is the first to examine RSFC of the central SMA in this population. Consequently, our results provide further validation to previous studies, supporting the existence of a central SMA with connectivity to both motor and language networks.

Keywords: functional MRI, resting state, functional connectivity, supplementary motor area (SMA), brain tumors

INTRODUCTION

The SMA (Brodmann cortical area 6c), described initially by Penfield and Welch, is located along the dorsomedial cortex in the superior frontal gyrus.1 This region has considerable functional significance, as it is involved in the planning, initiation, and execution of voluntary hand movements, unimanual and bimanual coordination, as well as multiple verbal processes, including word selection, encoding, verbal working memory, and articulation.2–7 Traditionally, the SMA has been divided into the rostral pre-SMA and caudal SMA proper. The SMA proper is considered important for motor task planning, while the pre-SMA is considered responsible for language-related functions.8–10 Findings on task-based functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) demonstrate preferential activation of the SMA proper during motor tasks and activation of the pre-SMA during specific cognitive language tasks, such as verb generation, semantic-based word generation, and reading.11

However, evidence shows that an additional functional region likely exists between and encompassing parts of both the pre-SMA and SMA proper.12,13 Resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) analyses in healthy controls have revealed functional differences within the SMA: compared to the posterior pre-SMA, the anterior pre-SMA showed connectivity to pre-frontal areas, but not to motor areas.13 Additional studies have demonstrated differences in fMRI activation within the central portion of the SMA. In fact, the performance of simultaneous motor and language fMRI tasks in healthy individuals showed maximal activation in a centralized zone between the pre-SMA and SMA proper.12 Other studies showed activation of the central SMA during motor imagery14 and motor preparation15 tasks.

Previous studies have shown the existence of the central SMA in healthy controls, but none have examined this region’s connectivity in brain tumor patients.12,14,15 These patients may suffer from neurocognitive deficits that impair the ability to cooperate with fMRI paradigms.16 Resting state fMRI (rs-fMRI) is a less demanding alternative, allowing for paradigm-free functional imaging based on spontaneous blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) fluctuations during rest.17 Rs-fMRI may be especially useful to examine the organization of the SMA, as it allows for identification of multiple networks from a single acquisition.16

Based on the previous literature, the central SMA may be an additional functional region with different functional properties than either the pre-SMA or the SMA proper. However, this is an area of study that needs further validation with different subject populations. Since it is unknown if the presence of tumor will cause disturbed RSFC of the SMA, examining the RSFC of the SMA subdivisions in this population will further extend our understanding of resting-state functional networks. The purpose of our study was therefore to evaluate the RSFC of the pre-SMA, the SMA proper, and the central SMA in brain tumor patients. Given the prior task-based fMRI work demonstrating that the central SMA shows maximal activation during the simultaneous execution of motor and language tasks,12 we hypothesized that RSFC originating from the central SMA will produce a map of both motor and language networks.

METHODS

Subjects

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board. A total of 14 patients (mean=46 years) were identified who completed task-based and rs-fMRI in addition to routine clinical MRI, and who also performed motor and language paradigms that activated the SMA proper and pre-SMA, respectively. All patients were left dominant for language on the task-based fMRI paradigms. In total, eleven patients were right handed and three were left handed as determined by the Edinburgh handedness inventory.18 The patient and tumor characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of patient and tumor characteristics.

| Patient | Age (years) | Gender | Handedness | Diagnosis | Tumor Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 53 | F | Left | anaplastic astrocytoma (grade III) | right frontal lobe |

| 2 | 46 | M | Right | oligodendroglioma (grade II/III) | right frontal lobe |

| 3 | 64 | F | Right | metastatic breast carcinoma | left frontal lobe |

| 4 | 33 | M | Right | metastatic lung adenocarcinoma | left frontoparietal junction |

| 5 | 53 | F | Right | glioblastoma (grade IV) | right insula, subinsula, & basal ganglia |

| 6 | 31 | M | Right | low-grade glioma (grade II) | left frontal lobe |

| 7 | 60 | M | Right | glioblastoma (grade IV) | right parietal lobe |

| 8 | 53 | F | Left | glioblastoma (grade IV) | left frontal lobe |

| 9 | 28 | M | Right | astrocytoma (grade II) | left frontal lobe |

| 10 | 51 | M | Right | glioblastoma (grade IV) | left temporal lobe |

| 11 | 53 | F | Right | metastatic poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma | left frontal lobe |

| 12 | 45 | M | Right | indeterminate | left parietal lobe |

| 13 | 23 | M | Right | glioblastoma (grade IV) | right posterior frontal lobe |

| 14 | 54 | F | Left | high-grade astrocytoma | right pre-central gyrus |

F = female; M = male.

MR Imaging

Images were acquired on a 3T GE magnet (Milwaukee, Wisconsin) using a 24 channel head coil. fMRI data was acquired with a single shot gradient echo echo-planar imaging sequence (TR/TE= 2500/35 ms; 64 × 64 matrix; 4 mm thickness, 240 mm FOV). The functional MR image resolution was 4×4×4 mm for both task-based and resting state fMRI. The number of image slices per TR ranged from 32-34. Functional matching T1-weighted spin-echo images (TR/TE= 600/8 ms, 256 × 256 matrix) and 3D T1-weighted anatomic images with a spoiled gradient-recalled-echo sequence (TR/TE= 22/4 ms, 256 × 256 matrix, 30° flip angle, 1 mm thickness, 240 mm FOV) were also acquired.

fMRI Paradigm and Data Analysis

All patients performed at least two paradigms: a motor task (finger tapping) and a language task (either semantic or phonemic fluency). Language tasks were used to localize the pre-SMA, Broca’s area (BA), and Wernicke’s area (WA). During the phonemic fluency task, different letters were presented visually and patients were required to silently generate words beginning with that letter. The semantic fluency task required patients to silently generate words belonging to presented categories. Each task consisted of 8 cycles of alternating activity (20 seconds) and rest (30 seconds) in which patients were given visual cueing. For the rs-fMRI, patients were instructed to try not to think of anything for the duration of the scan. The rs-fMRI scan duration was 6 minutes and 40 seconds.

Images were analyzed using Analysis of Functional Neuroimaging (AFNI) software.19 Processing and analysis were performed in native rather than standard space to remove any risk of error propagation during analysis and due to the presence of large tumors, which occasionally can make registration to standard space precarious. Head motion correction, spatial smoothing (Gaussian filter with 4-mm full width of half maximum), and corrections for linear trend and high frequency noise were applied. For cases showing false positive activity from large venous structures or head motion, voxels in which the standard deviation of the acquired time series exceeded 5% of the mean signal intensity were set to zero.

For rs-fMRI data, spontaneous low-frequency fluctuations (0.01-0.08 Hz) were filtered to remove respiratory and cardiac input and to extract frequencies of spontaneous fluctuations associated with functional resting state. For cases showing a mismatch between tb-fMRI and rs-fMRI, we co-registered both images based on a reference volume chosen from the tb-fMRI images. Functional activity was generated using a correlation analysis. A modeled waveform corresponding to the task performance block was cross-correlated with all pixel time courses on a pixel-by-pixel basis. A threshold of P < 0.001 was used.

From the task-based fMRI map, voxels with maximal activation in the pre-SMA and SMA proper of the dominant hemisphere were selected and used to create spherical regions of interest (ROIs), each with a radius of 6mm. The ROIs were individually superimposed on the rs-fMRI data and used to generate both motor and language RSFC maps. The coordinates identified from task-based fMRI were then averaged to select a point midway between the two areas. A third ROI was then placed at this point to obtain a RSFC map of the central SMA [Fig. 1]. The location of the central SMA was calculated based on a previously described methodology12. Through this method, for each subject, whole brain RSFC maps were generated from three different ROIs within the SMA: 1) pre-SMA (language network) 2) SMA proper (motor network), and 3) central SMA (both language and motor networks). Voxels were significant at a threshold of p<.001.

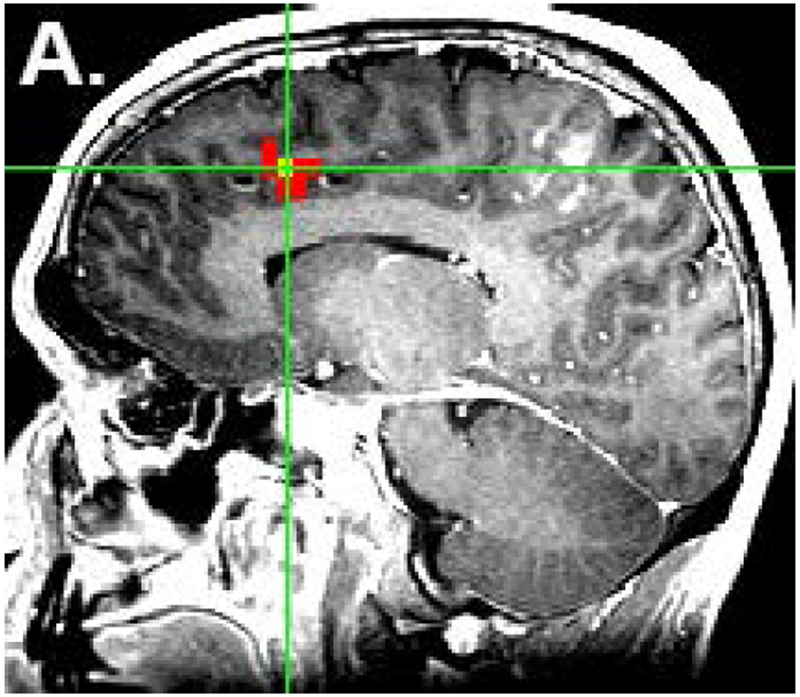

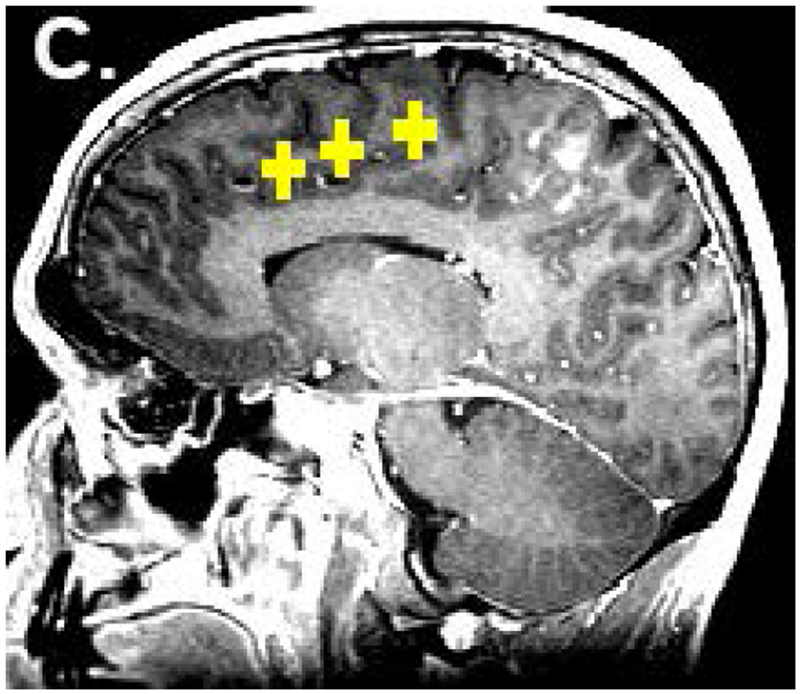

Figure 1:

Placement of ROIs. The locations of the pre-SMA (a) and SMA proper (b) were identified from task-based fMRI. ROIs were placed in these two locations as well as in the central SMA (c). The colored voxels represent the strength of correlation of the SMA with an ideal boxcar waveform, according to the following: 0-0.3 (not significant) < 0.3-0.8 (red) < 0.8-1.0 (yellow). Voxels highly correlated with the ideal waveform are yellow, while voxels that are less highly correlated (for which the maximum p value is less than 0.001) are red. The yellow color of the ROIs in figure 1c has no functional significance and is for illustration only.

As a quantitative analysis, the degree of connectivity was measured based on the cross-correlation of each sub-region of the SMA to both BA and the motor gyrus. Since all patients displayed left hemisphere language dominance as determined by a board-certified neuroradiologist with 20+ years of experience in fMRI, ROIs were placed in the dominant left hemisphere. In each case, we used AFNI to draw one ROI around the anatomical left BA, and a second ROI around the left motor gyrus. Within each ROI, we selected the ten voxels most highly correlated with the pre-SMA, central SMA, and SMA proper. The average correlation values were used to compare the connectivity of the subdivisions of the SMA with both the motor and language areas. The non-parametric Friedman test was first used to compare the overall differences between the three regions of the SMA in terms of connectivity. In addition, the Mann-Whitney U-Test was used to compare the RSFC of the pre-SMA, central SMA, and SMA proper to BA and the motor gyrus.

RESULTS

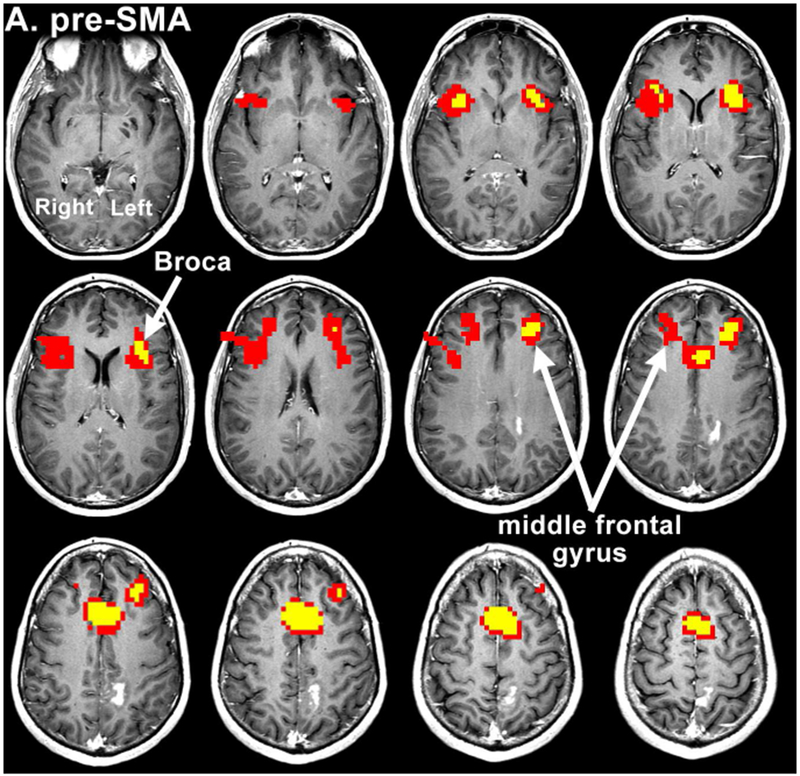

Qualitative visual analysis showed RSFC between the pre-SMA and the language centers (either BA or WA) of the dominant left hemisphere in all cases, especially BA in the dominant hemisphere. Similarly, all patients showed RSFC between the SMA proper and pre-central gyrus of the ipsilateral dominant (left) hemisphere, with minimal connectivity to the language centers in two cases. Central SMA maps revealed RSFC to both language and motor areas in thirteen out of fourteen cases (92.9%). In one case, however, the central SMA map showed RSFC to language areas only, without any appreciable motor RSFC.

In terms of language connectivity, maps with a central SMA seed showed RSFC to BA and the right BA analogue in eleven cases, compared to ten cases with a pre-SMA seed. Connectivity to WA and the right WA analogue was more frequently bilateral with a central SMA seed (9/14 cases) than with a pre-SMA seed (2/14 cases). However, the overall RSFC of the central SMA resembled the individual RSFC maps of both the SMA proper and pre-SMA. One representative example is shown in Figure 2.

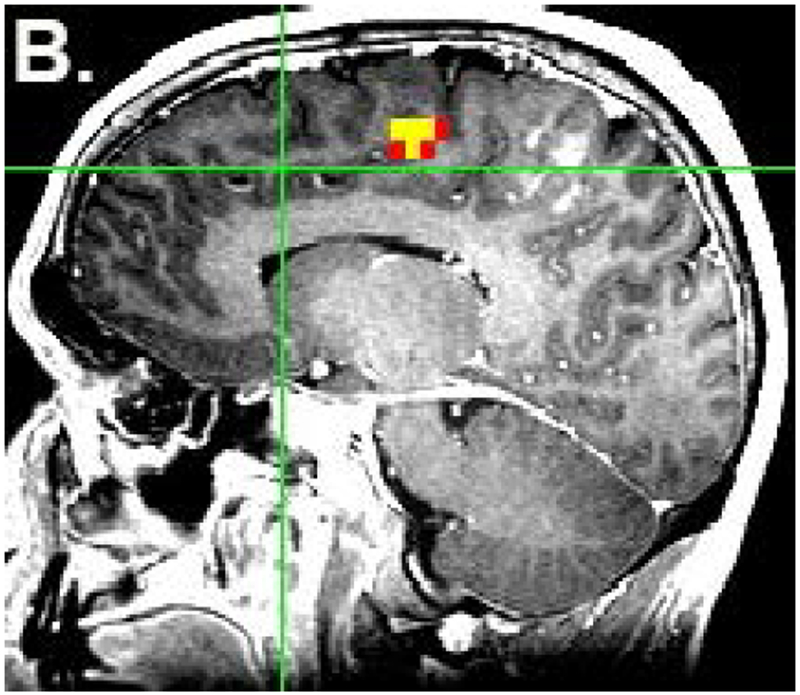

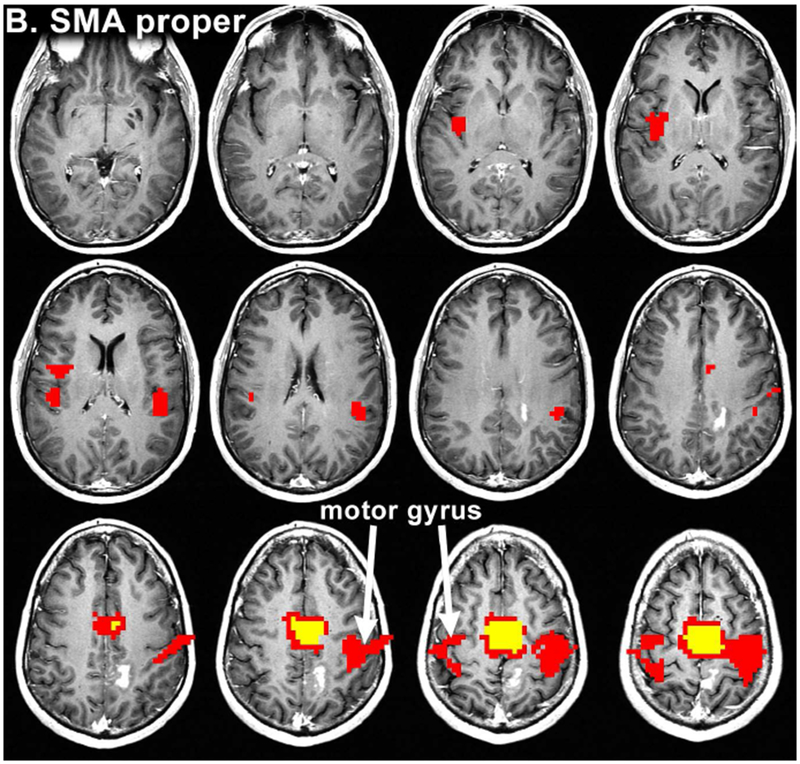

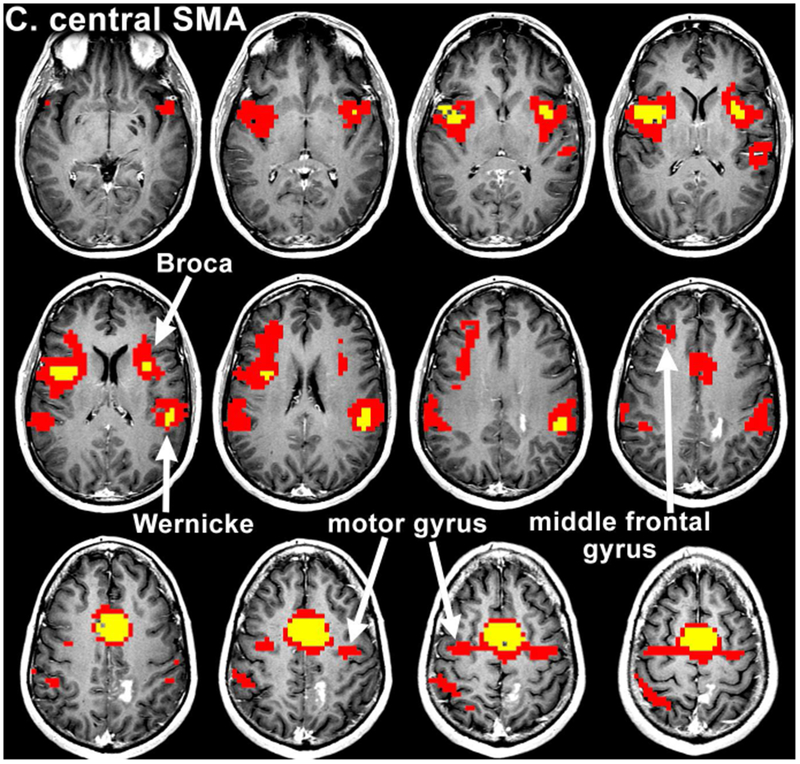

Figure 2:

Resting state connectivity maps from Patient 12. The maps were obtained after seeding of the pre-SMA (a), SMA proper (b) and central SMA (c), showing an overlap of language and motor areas on central SMA seeding. The colored voxels visualize the strength of correlation of several seed ROIs with the resting state functional data, according to the following: 0-0.3 (not significant) < 0.3-0.8 (red) < 0.8-1.0 (yellow). Voxels highly correlated with the average timeseries of the seed ROI are yellow, while voxels that are less highly correlated (for which the maximum p value is less than 0.001) are red.

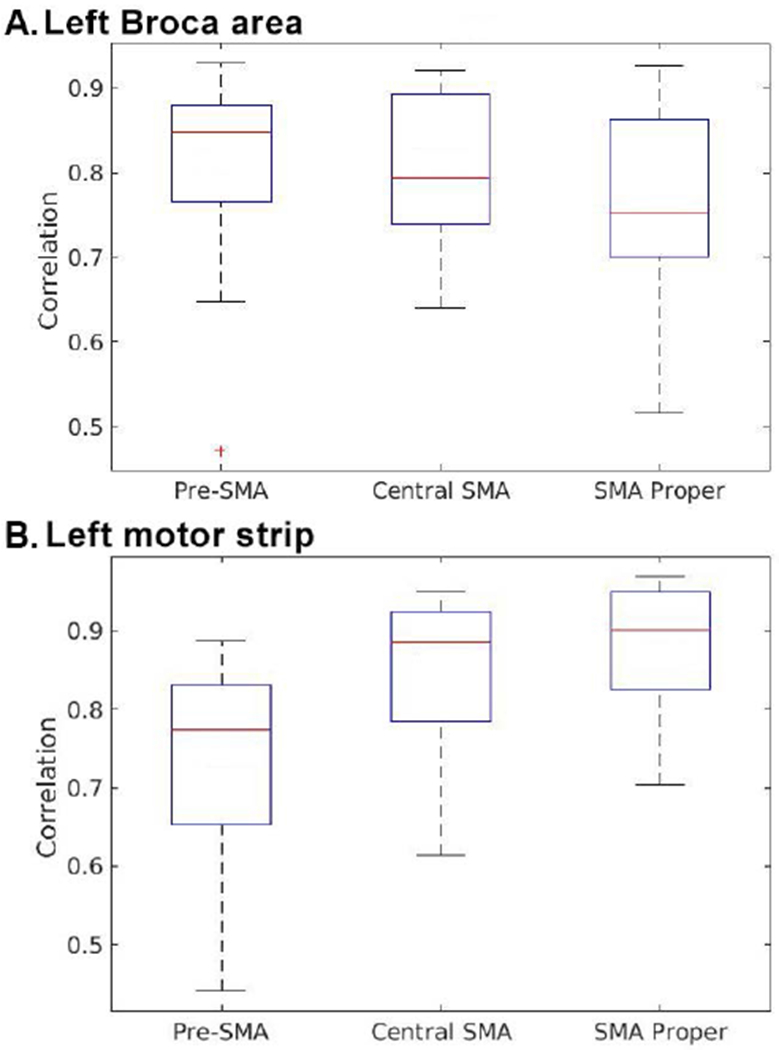

Subsequently, quantitative analysis of RSFC was performed in the dominant hemisphere. Regarding connectivity to BA, the correlation with the pre-SMA was 0.801 (SD = 0.121) and the correlation with the central SMA was 0.803 (SD = 0.095). Between the SMA proper and BA, connectivity was relatively lower at 0.760 (SD = 0.112). The average correlation was used to compare the degree of RSFC between BA and each subdivision of the SMA. Comparison was performed using a Friedman test showing no statistically significant difference within the SMA in terms of connectivity to BA (χ2[2] = 2.286, p = 0.319). Additional paired Mann-Whitney U-Tests showed no statistically significant difference in connectivity to BA between individual regions of the SMA (pre-SMA vs. central SMA, U = 94, p = 0.87; SMA proper vs central SMA, U = 76, p = 0.32; pre-SMA vs. SMA proper, U = 73, p = 0.26).

The Friedman test was again used to compare the SMA regions in terms of connectivity to the left motor gyrus, showing a statistically significant difference (χ2[2] = 19.000, p < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis was performed with paired Mann-Whitney U-Tests. The correlation of the motor gyrus with the SMA proper was 0.883 (SD = 0.080) and with the central SMA was 0.842 (SD = 0.108). A Mann-Whitney U-Test showed no statistically significant difference in motor RSFC between these groups, U = 73, p = 0.26. The correlation between the pre-SMA and motor gyrus, however, was relatively lower, at 0.732 (SD = 0.134). Mann-Whitney U-Tests indicated that this reduced motor connectivity was significant (pre-SMA vs. central SMA, U = 45, p = 0.016; pre-SMA vs. SMA proper, U = 28, p = 0.00142). Figure 3 summarizes the results of the correlation analysis.

Figure 3:

Degree of connectivity between the SMA (pre-SMA, central SMA, and SMA proper) and (a) the left Broca’s area and (b) the left motor strip.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates RSFC of the SMA subdivisions in brain tumor patients. Additionally, our results show that the central SMA demonstrates reliable connectivity to both Broca’s area and hand motor area. Our findings are supported by the observations of Peck et al.12, who noted that a combined motor and language paradigm resulted in a maximal area of activation in the central SMA that was more robust than either pre-SMA or SMA proper activation during individual tasks. The authors attributed this to the enhanced cooperativity between the pre-SMA and SMA proper while performing a complex task.

We found that connectivity with BA does not differ significantly throughout the SMA, showing that language RSFC is not isolated to the pre-SMA. Despite a paucity of SMA proper activation during task-based language fMRI, RSFC between SMA proper and BA may reflect the motor components of language. On the other hand, the pre-SMA was significantly less connected to the motor gyrus than the rest of the SMA. Connectivity to the motor gyrus appears to be stronger in the central and posterior aspects of the SMA. The gradient appears steeper for motor than for language connectivity, such that anterior and posterior components of the SMA differ significantly. Our observations are in a good agreement with the findings noted by Zhang et al., who showed stronger connectivity between the motor gyrus and the posterior pre-SMA when compared to the anterior pre-SMA.13 These findings are also in line with the observations by Kim et al, who felt that the SMA could have up to 3 functional subdivisions.20

Consequently, our results suggest that the RSFC of the central SMA resembles that of the posterior motor and anterior language components of the SMA. This is not entirely surprising, since studies of receptor-expression maps have convincingly demonstrated existence of a smooth continuum of changes in the expression of different receptors.21 In addition, our findings are supported by prior studies showing that the projections to the subthalamic nuclei from the pre-SMA and SMA partly overlap.22 Our findings also concur with the meta-analysis by Mayka et al., in which authors integrated functional data from multiple tasks and noted an overlap between the pre-SMA and SMA proper, without any distinct clustering.23 Additionally, our findings demonstrate that the central SMA shows reliable connectivity to the BA and pre-central gyrus, which may aid in pre-operative localization of eloquent regions using only rs-fMRI.

Connectivity to multiple functional networks makes the SMA important from a neurosurgical perspective. Resections in this region are associated with SMA syndrome, which is characterized by immediate post-surgical development of contralateral motor and language deficits, and seen in up to 26% of superior frontal glioma resections.10,24,25 Although SMA syndrome typically follows resections of the SMA proper, it is well-recognized that resections anterior to the SMA proper can also cause SMA syndrome, with both motor and language deficits.25 Fontaine et al. also noted post-surgical language deficits in more posterior resections, suggesting the extension of language function into the anterior SMA proper, perhaps in the central SMA.24 Our finding that the central SMA demonstrates motor and language RSFC aligns with these results, strengthening the idea that portions of the SMA have both motor and language functionality.

A limitation of our study is that the location of the central SMA was calculated as the midway point between the pre-SMA and SMA proper. It is possible this method led us to place ROIs such that they only partially encompassed the true central SMA. Since some subjects had tumors in the dominant hemisphere or close to eloquent areas, microscopic tumor infiltration and neurovascular uncoupling on RSFC cannot be excluded, especially for subjects with high grade lesions.26 For example, the only case which did not show motor RSFC had a lesion in the motor strip. Future studies may seek to examine the SMA with multiple smaller ROIs to more precisely characterize the RSFC of this region in brain tumor patients.

Another significant limitation of our study is lack of a healthy control group. Even though previous studies on healthy controls have shown results consistent with our observations, they were performed using similar, but not identical methodologies.13,20 Furthermore, since our cohort only had two patients with low grade gliomas, a larger study in this cohort would be better placed to further define if infiltration of the SMA affects the RSFC to the language and motor areas.

Rs-fMRI analysis of the SMA in brain tumor patients demonstrates that there is strong and reliable RSFC between the central SMA and both motor and language networks. This study is the first to confirm the RSFC of SMA subdivisions in brain tumor patients with important implications for the planning of neurosurgery. These findings support the existence of underlying functional subdivisions within the SMA and provide further evidence for a central portion of the SMA with both motor and language connectivity.

Acknowledgments and Disclosure:

This study was funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH), NIH-NIBIB 1R01EB022720-01 (Makse and Holodny, PI’s) and U54 CA 137788 (Ahles, PI). The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References:

- 1.Penfield W, Welch K. The supplementary motor area of the cerebral cortex; a clinical and experimental study. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1951;66:289–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alario FX, Chainay H, Lehericy S, Cohen L. The role of the supplementary motor area (SMA) in word production. Brain Res 2006;1076:129–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vergani F, Lacerda L, Martino J, et al. White matter connections of the supplementary motor area in humans. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:1377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Esposito M, Detre JA, Alsop DC, Shin RK, Atlas S, Grossman M. The neural basis of the central executive system of working memory. Nature 1995;378:279–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diedrichsen J, Grafton S, Albert N, Hazeltine E, Ivry RB. Goal-selection and movement-related conflict during bimanual reaching movements. Cereb Cortex 2006;16:1729–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krainik A, Lehericy S, Duffau H, et al. Role of the supplementary motor area in motor deficit following medial frontal lobe surgery. Neurology 2001;57:871–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadato N, Yonekura Y, Waki A, Yamada H, Ishii Y. Role of the supplementary motor area and the right premotor cortex in the coordination of bimanual finger movements. J Neurosci 1997;17:9667–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuzaka Y, Aizawa H, Tanji J. A motor area rostral to the supplementary motor area (presupplementary motor area) in the monkey: neuronal activity during a learned motor task. J Neurophysiol 1992;68:653–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanji J The supplementary motor area in the cerebral cortex. Neurosci Res 1994;19:251–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenabi M, Peck KK, Young RJ, Brennan N, Holodny AI. Probabilistic fiber tracking of the language and motor white matter pathways of the supplementary motor area (SMA) in patients with brain tumors. J Neuroradiol 2014;41:342–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lou W, Peck KK, Brennan N, Mallela A, Holodny A. Left-lateralization of resting state functional connectivity between the presupplementary motor area and primary language areas. Neuroreport 2017;28:545–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peck KK, Bradbury M, Psaty EL, Brennan NP, Holodny AI. Joint activation of the supplementary motor area and presupplementary motor area during simultaneous motor and language functional MRI. Neuroreport 2009;20:487–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang S, Ide JS, Li CS. Resting-state functional connectivity of the medial superior frontal cortex. Cereb Cortex 2012;22:99–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephan KM, Fink GR, Passingham RE, et al. Functional anatomy of the mental representation of upper extremity movements in healthy subjects. J Neurophysiol 1995;73:373–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee KM, Chang KH, Roh JK. Subregions within the supplementary motor area activated at different stages of movement preparation and execution. Neuroimage 1999;9:117–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee MH, Smyser CD, Shimony JS. Resting-state fMRI: a review of methods and clinical applications. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013;34:1866–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med 1995;34:537–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971;9:97–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res 1996;29:162–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JH, Lee JM, Jo HJ, et al. Defining functional SMA and pre-SMA subregions in human MFC using resting state fMRI: functional connectivity-based parcellation method. Neuroimage 2010;49:2375–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geyer S, Matelli M, Luppino G, et al. Receptor autoradiographic mapping of the mesial motor and premotor cortex of the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol 1998;397:231–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inase M, Tokuno H, Nambu A, Akazawa T, Takada M. Corticostriatal and corticosubthalamic input zones from the presupplementary motor area in the macaque monkey: comparison with the input zones from the supplementary motor area. Brain Res 1999;833:191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayka MA, Corcos DM, Leurgans SE, Vaillancourt DE. Three-dimensional locations and boundaries of motor and premotor cortices as defined by functional brain imaging: a meta-analysis. Neuroimage 2006;31:1453–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fontaine D, Capelle L, Duffau H. Somatotopy of the supplementary motor area: evidence from correlation of the extent of surgical resection with the clinical patterns of deficit. Neurosurgery 2002;50:297–303; discussion 303-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ibe Y, Tosaka M, Horiguchi K, et al. Resection extent of the supplementary motor area and post-operative neurological deficits in glioma surgery. Br J Neurosurg 2016;30:323–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agarwal S, Sair HI, Yahyavi-Firouz-Abadi N, Airan R, Pillai JJ. Neurovascular uncoupling in resting state fMRI demonstrated in patients with primary brain gliomas. J Magn Reson Imaging 2016;43:620–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]