Abstract

Background & Aims:

Management of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases often requires lifelong immunosuppression. Increasing numbers of older patients have inflammatory diseases and are particularly vulnerable to risks of immune suppressive therapies—particularly infections and malignancies.

Methods:

We systematically searched PubMed/Medline and Embase to identify eligible studies that examined the safety of biologic therapies in older patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis). Included studies provided information on patients who began receiving therapy with a biologic agent when they were older than 60 years and a control population (either younger users of biologics or older patients who did not use biologics). Information of on overall pooled rates of infections, malignancy, and mortality were extracted. A DerSimonian and Laird random effects model was used to calculate pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs.

Results:

Our meta-analysis included 14 unique studies that comprised 4719 older users of biologics, 13,305 younger users of biologics, and 3961 older patients who did not use biologics. The pooled prevalence of infections in older and younger users of biologics was 13% and 6% respectively, yielding a pooled random effects odds ratio of 2.28 (95% CI, 1.57–3.31). Older age was associated with a significant increase in risk of malignancy (OR, 3.07; 95% CI, 1.98–4.62) compared to younger age. Older users of biologics had a 3-fold increase in risk of infection compared to patients who did not use biologics (OR, 3.60; 95% CI, 1.62–8.01), but there were no significant differences in odds of malignancy (0.54, 95% CI, 0.28–1.05) or death (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.44–5.28) compared to older patients who did not use biologics.

Conclusion:

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on the safety of biologic therapies in older patients with inflammatory diseases, we found that older users of biologic agents have an increased risk of infections compared with younger users or older patients who do not use biologics. Large, prospective cohort studies are needed to examine safety of biologic therapy in older patients with immune-mediated diseases

Keywords: tumor necrosis factor, anti-TNF, elderly, IBD, drug, anti-TNF therapy, autoimmune disease, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, safety

INTRODUCTION

With the rising life expectancy worldwide and improvements in treatment of various immune-mediated diseases (IMD), the number of older individuals with an IMD will continue to expand. Treatment of older patients with a chronic IMD can pose certain unique challenges. Advanced age is a risk factor for several comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease1, diabetes2 and cancer which complicate the use of immunosuppressive therapy3. In addition, there may be age-related changes in the pharmacokinetic properties of therapy including absorption, distribution and excretion when compared to the younger age population4.

The cornerstone of treatment for IMDs remains life-long immunosuppression. In particular, monoclonal antibodies targeting various inflammatory cytokines have emerged as a key component of the therapeutic algorithm for inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD; Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC)), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and psoriasis (Ps). In each of these diseases, biologic therapies are effective for both inducing and maintaining remission. In the younger patient, while there are recognized risks including that of immunosuppression-related cancers, serious or opportunistic infection, the absolute rate of occurrence of these events is relatively low and the risk-benefit profile favors use in most5. However, extrapolation of that safety to older patients is challenging for various reasons. First, older patients were excluded or under-represented in most registration clinical trials for these agents. It was noted that older patients were more likely to withdraw due to drug toxicity6. Observational studies examining drug-safety in older patients had small sample sizes limiting generalizability7–9. Older age itself increases susceptibility to various therapy related complication, and the consequences of such complications could be more impactful in this population. Thus, there is an important need for systematic study of the safety of biologic therapy in older IMD patients to robustly inform clinical practice.

We performed this systematic review and meta-analysis to calculate the pooled safety of biologic therapy in older patients with IMD when compared to similar patients on non-biologic therapies or younger biologic users. We elected to examine biologic use across a spectrum of indications rather than focus on one disease to provide the most generalizable estimate of safety in this vulnerable population.

METHODS

Literature search

We performed a systematic electronic search of the MEDLINE and Embase databases to identify eligible studies examining safety of biologic therapy in older patients with IMD. Our search encompassed articles published from the inception of MEDLINE and Embase till June 2018. We did not apply any language restrictions but required at least the abstract to be available in English. Our search combined four different phrase groups by using the Boolean operator “AND”. The first phrase included terms to define IMDs and included “autoimmune disease”, “inflammatory bowel disease”, “Crohn’s disease”, “Ulcerative colitis”, “Psoriasis”, and “rheumatoid arthritis”. The second group consisted of terms to identify biologic therapies and included anti-TNF therapy, anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha, biologics, biologic therapy, biological, adalimumab, infliximab, certolizumab, golimumab, etanercept, or ustekinumab. The third search entailed terms to define older patients: elderly, old, older patients, aged and advanced age. The final group defined the outcome of interest and included safety, tolerance, effectiveness, efficacy, infection, malignancy and cancer.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they (1) included patients with IMD on biologic therapy; and (2) provided specific data on infection or malignancy rates in older biologic users ≥ 60 years of age; and (3) included a comparison group of either younger patients (< 60 years) on biologic therapies or patients older than 60 years on non-biologic treatments or both. Studies examining biologic use among cohorts of younger patients only (<60 year) or case series of older biologic users not including a control population, or those providing insufficient data to estimate event rates or odds ratios were excluded. As well, case-control studies with fewer than 10 older patients on biologic therapy were excluded.

Data collection

The title and abstract of all eligible studies were screened and decision for inclusion of was made independently by the two authors. Disagreements were settled through consensus. From each study, year of publication, population (IMD type, control groups), number of patients, type of biologic therapy, concomitant use of other immunomodulators and steroids were noted. Data were extracted for overall rates of any infection, serious infection, and specific type of infection within the first year of therapy initiation, consistent with pharmacoepidemiologic analysis. Pooled infection rates for each specific infection type was estimated only when it was reported in > 1 study. Cumulative rates of malignancy during the first year of treatment were noted for all patient groups, and separated out into systemic and cutaneous cancers where possible. Information about overall mortality was also extracted from each of the studies.

Assessment of study quality

The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) was applied to assess quality of the included studies10 (Supplemental Table 1). This scale consists of three ranking groups based on: the selection of the cohort, the comparability of the cohorts and the completeness of ascertainment of the outcome. Studies were considered representative if they consisted of an unselected group of patients. Each study could receive a maximum score of 8.

Statistical analysis

Heterogeneity between the studies was calculated using the Cochrane’s Q and I2 statistics. An I2 > 50% or p < 0.10 indicated significant heterogeneity. A DerSimonian and Laird random effects model was used for all analyses to determine the pooled odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI)11. Analysis was performed separately for all infections, specific infections (when outcomes were reported in ≥ 2 studies) and malignancy. Separate analyses were conducted comparing rates of study outcomes in older biologic users compared to younger biologic users, and older non-biologic users. Pre-specified subgroup analysis was performed stratifying by type of IMD (IBD, Psoriasis, RA). A two-sided p-value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance of the pooled estimate. In addition to pooled odds ratios, the metaprop command was used to estimate pooled rates of events (infection, malignancy, death) in each group12. Significance of between group differences was similarly estimated using a t-test and labeled significant at p < 0.05. We assessed for publication bias by visual examination of the funnel plot as well as Begg’s and Egger tests. Meta-regression was used to identify influential variables. All statistical analysis was carried out using Stata 13.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Literature search

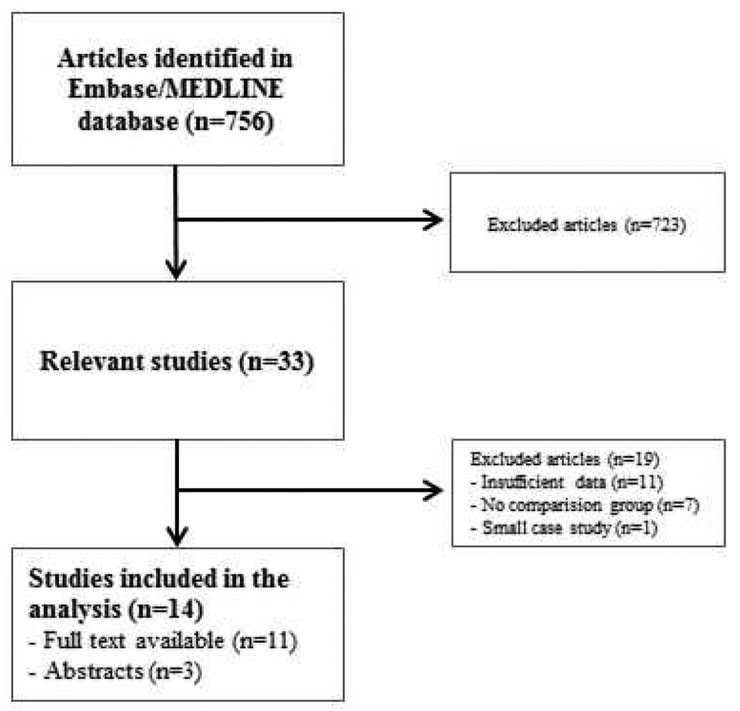

Our initial literature search identified 756 relevant studies on MEDLINE/Embase from inception till June 2018. Upon review of title and abstract, 33 articles were selected for full-text review (Figure 1). Among these, 19 additional studies were excluded. Three studies had no detailed data available regarding safety outcomes13–15, two studies were not accessible in full-text16, 17 and one study was excluded because it included fewer than 10 patients18. Thirteen studies were excluded because they did not have sufficient data for the control population19–31. Thus, our final analysis included 14 unique studies7, 8, 32–43. Of these, three studies had only the abstract available for review, but sufficient detailed information could be extracted to allow for inclusion38, 42, 43. Most studies were retrospective cohorts; only 2 were prospective studies36, 39.

Figure 1:

Flow chart of the literature search

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the eligible studies are summarized in Table 1. Together, the included studies comprised 21,985 patients with IMD comprising 4,719 older biologic users, 13,305 young biologic users and 3,961 older control non-biologic users. Twelve studies compared the safety of biologics in older compared to younger patients while eight studies compared the safety of biologics in older patients compared to an older non-biologic control population. Of these 14 studies, 6 were among patients with IBD7, 8, 32, 33, 42, 43 (n=349 older biologic patients), 1 study included those with psoriasis (n=135 older biologic patients)41 and 7 examined those with RA (n=4,235 older biologic patients)34–40. The mean age of included participants was 71 years for older biologic users (data from 11 studies), 43 years for younger biologic users (data from 10 studies) and 72 years in the older non-biologic control patients (6 studies). More than half the patients in each subgroup were women (61% of older biologic users (9 studies), 65% of younger biologic users (8 studies), and 51% of older controls (3 studies).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis

| Year | Author | Disease | Study Design | Age cut off (in years) | Biologic therapy included | Total number of included patients | Number of older biologic users | Younger control population | n | Older control population | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | Cottone M33 | IBD | Retrospective | ≥65 | Adalimumab, Infliximab | 475 | 95 | Adult matched control subjects treated with biologics | 190 | Older non-biologic users | 190 |

| 2013 | Desai A8 | IBD | Retrospective | ≥60 | Adalimumab, Infliximab | 162 | 54 | Younger anti-TNF users | 54 | Older non-biologic patients using Azathioprine or 6-MP | 54 |

| 2014 | Shen H32 | IBD | N/A | ≥65 | Adalimumab, Infliximab, Certolizumab | 54 | 16 | Younger anti-TNF users | 38 | ||

| 2015 | Lobaton T7 | IBD | Retrospective | ≥65 | Adalimumab, Infliximab | 239 | 66 | Younger anti-TNF users | 112 | Older non-biologic users using immunomodulators and/or corticosteroids | 61 |

| 2015 | van der Vliet QM42 | IBD | Retrospective | ≥60 | Anti-TNF therapy, not specified | 472 | 93 | Younger anti-TNF users | 234 | Older naïve anti-TNF patients | 145 |

| 2017 | Maia L43 | IBD | Retrospective | ≥65 | Adalimumab, Infliximab | 219 | 25 | Younger anti-TNF users | 194 | ||

| 2014 | Piaserico S41 | Psoriasis | Retrospective | ≥65 | Adalimumab, Infliximab, Etanercept, Efalizumab, Ustekinumab | 321 | 135 | Older nonbiologic users | 186 | ||

| 2006 | Bathon JM36 | RA | Prospective | ≥65 | Etanercept | 1847 | 308 | Adult matched control subjects treated with biologics | 1539 | ||

| 2007 | Genevay S37 | RA | Retrospective | ≥65 | Adalimumab, Infliximab, Etanercept | 1571 | 344 | Younger anti-TNF users | 1227 | ||

| 2007 | Schneeweiss S40 | RA | Retrospective | ≥65 | Adalimumab, Infliximab, Etanercept | 2369 | 469 | Older non-biologic users on MTX | 1900 | ||

| 2008 | Filippini M9 | RA | Retrospective | ≥65 | Adalimumab, Infliximab, Etanercept | 295 | 105 | Younger anti-TNF users | 190 | ||

| 2011 | Galloway JB39 | RA | Prospective | ≥65 | Adalimumab, Infliximab, Etanercept | 13088 | 2767 | Younger anti-TNF users | 9031 | Older non-biologic users on DMARDs | 1290 |

| 2016 | Murota A34 | RA | Retrospective | ≥65 | Adalimumab, Infliximab, Certolizumab, Etanercept | 444 | 135 | Younger anti-TNF users | 174 | Older non-biologic users on DMARDs | 135 |

| 2016 | Cho SK35 | RA | Retrospective | ≥60 | Adalimumab, Infliximab, Etanercept | 429 | 107 | Younger anti-TNF users | 322 |

A total of 12 studies each included patients on adalimumab and infliximab therapy respectively, 8 for etanercept, 2 for certolizumab, and 1 each for ustekinumab and efalizumab. Etanercept therapy was most widely used in RA studies with 55% of older and younger biologic users receiving etanercept in our meta-analysis (range 32% - 100%). A total of 45% older biologic users (range 15% - 79%) were on combination therapy with an immunomodulator compared to 53% in younger biologic users (range 26% - 89%). Similar rates of concomitant steroid use were found between older biologic users, younger biologic users and older nonbiologic users (64%, 61% and 62% respectively). The studies also varied in the definition of infections. Five studies requiring the need for intravenous antibiotic administration and hospitalization for defining a serious infection while the others reported a composite of any infection (mild or serious) including opportunistic infections. There was also heterogeneity in the comorbidities adjusted for with 7 studies using either the Charlson comorbidity index or some components of it to quantify comorbidity. Other studies did not adjust for general comorbidity.

Risk of infection and other outcomes among older patients on anti-TNF therapy

(a) Older biologic users compared to younger biologic users

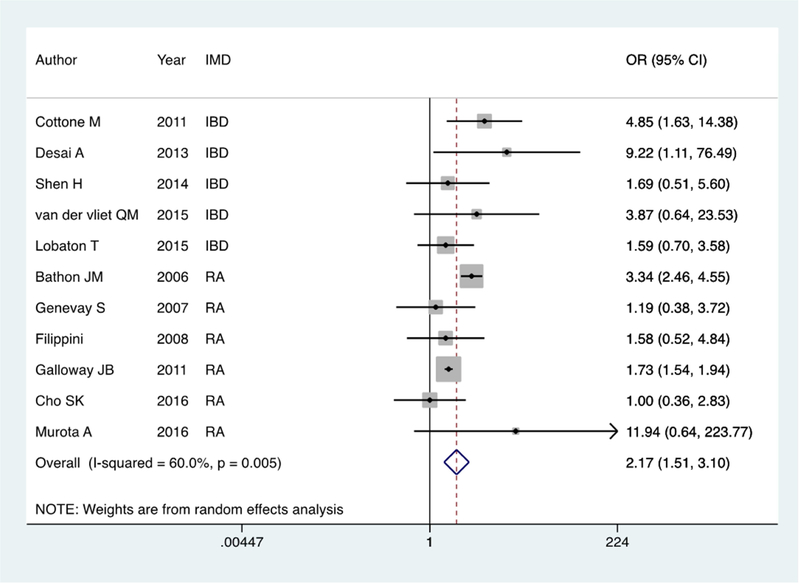

Twelve studies (1,323 older biologic users, 13,111 younger biologic users) provided detailed data on infection rates within the first year on biologic therapy. The studies included patients on adalimumab (9 studies), infliximab (9 studies), certolizumab (2 studies), and etanercept (6 studies). The pooled prevalence of infections in older and younger biologic users was 13% and 6% respectively. Using a Der Simonian and Laird random effects meta-analysis model, older biologic users were twice as likely to develop an infection within the first year as younger biologic users (OR 2.28, 95% CI 1.57 – 3.31) (Figure 2a). There was significant heterogeneity with an I2 of 63.5% (p=0.003). The only infection with > 1 study reporting data on specific rates was pneumonia. Older biologic users were three-times as likely to develop pneumonia as younger biologic users (OR 3.09, 95% CI 1.02 – 9.39) (Supplemental Figure 1). The pooled prevalence of malignancy and mortality were 3% and 4% in older biologic users and 2% and 2% in younger biologic users. On random effects meta-analysis, older age was associated with a significant increase in risk of malignancy (OR 3.07, 95% CI 1.98 – 4.62) (Supplemental Figure 2a) and mortality (OR 6.35, 95% CI 2.29 – 17.64) compared to younger patients. There was no heterogeneity between the studies for the latter two outcomes. Among the different cancers, only one study reported on the rate of lymphoma. The authors found no difference in the rate of lymphoma in younger and older biologic users with both groups having a rate higher than expected in the general population. The other cancers reported included colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, and skin cancer but there was not sufficient information to present comparison stratified by cancer type.

Figure 2:

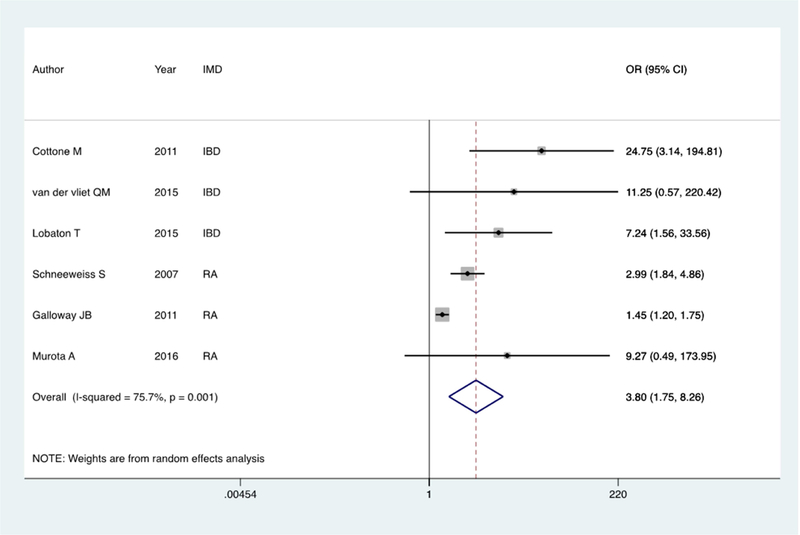

Forest plot of pooled infection risk among older patients with an IMD on biologic therapy compared to controls; 2a: Older biologic users compared to younger biologic users Figure 2: Forest plot of pooled infection risk among older patients with an IMD on biologic therapy compared to controls; 2b: Older biologic users compared to older non-users

(b) Older biologic users compared to older non-biologic users

There were eight studies that provided sufficient information to compare the risk of infection or malignancy in older biologic users compared to older patients not on biologic therapy. Of these, 3 each examined patients with IBD and RA and 1 examined those with psoriasis. Together, these studies comprised 3,760 older biologic users and 3,907 non-biologic users. The control populations examined included older biologic naïve patients with IMD and often on immunomodulator or corticosteroid therapy (5 studies). The proportion of infection in older biologic and non-biologic users was 10% and 5% respectively, yielding a pooled random effects odds ratio of 3.60 (95% CI 1.62 – 8.01) (Figure 2b). There was significant heterogeneity between the studies (I2=80%, p=0.001) and the individual odds ratios ranged from 1.45 to 24.75. The rates of cancer were similar in biologic users (2%) compared to older controls (4%) with a pooled odds ratio of 0.54 (95% CI 0.28 – 1.05) (Supplemental Figure 2b). Based on 4 studies, there was also no increase in mortality with biologic use in older patients compared to controls (OR 1.52, 95% CI 0.44 – 5.28).

Comparison of outcomes among older patients with IBD

We repeated our analysis, restricting to the six studies including patients with IBD (Supplemental Table 1). Compared to younger IBD patients who were biologic users, older biologic users had three times the risk of infection (OR 3.48, 95% CI 1.98 – 6.14) and an elevated risk of malignancy (OR 3.47, 95% CI 1.71 – 7.03). This excess risk of infection in older compared to younger biologic users was higher in those with IBD than in RA (p=0.09) (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Figure 3). Compared to older non-biologic users, older biologic users with IBD were significantly more likely to develop infections (OR 11.22, 95% CI 3.60 – 34.99) but due to smaller studies, the confidence estimates were wide.

Sensitivity analysis by age cut-off

We repeated our analysis, comparing the 11 studies that used an age cut-off of 65 years to the 3 studies that used an age cut-off of 60 years (Supplemental Table 2). Both groups revealed a similar direction of effect in terms of excess risk of infection or malignancy though the confidence intervals were wide for studies using the age cut-off of 60 years due to paucity of data. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups of studies.

Study quality and publication bias

Supplemental table 3 presents the quality scores for the included studies. While not all fields of the NOS were applicable for our meta-analysis, all studies were deemed of adequate quality to be included in the analysis. The Begg test showed no significant likelihood of publication bias (p=0.216) while the Egger test showed some likelihood of publication bias (p=0.004) (Supplemental Figure 4). Meta-regression revealed none of the variables to exert an independent influence on the risk of infections or malignancy in older biologic users (Supplemental Table 4).

DISCUSSION

The therapeutic armamentarium for chronic immune-mediated diseases has considerably expanded with the introduction of more effective biologic therapies leading to improved patient outcomes. However, safety concerns, particularly risk of infection and malignancy remain. A population that is particularly vulnerable to those risks yet under-represented in cohorts and clinical trials, is the older patient. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we quantify the risk of infection, malignancy, and mortality in older biologic users and demonstrated an increased risk compared to older non-users and younger patients.

Our meta-analysis demonstrated a pooled prevalence of infections of 13% among older IMD patients who were twice as likely to develop an infection within the first year as younger biologic users. Similar findings were reported in individual studies, for example that of IBD patients by Cottone et al.33. In this retrospective multicenter study, the authors reported a significantly increased risk of severe infections in older patients compared to younger individuals (13% vs. 3%). In addition, they noted higher rates of malignancy (3% vs 0%) and mortality (10% vs 1%) in older IBD patients using biologic therapy compared to younger individuals. Similar results were also noted by other reports where older IBD patients who used biologics were more likely to develop infections compared to younger patients (15% vs. 6%; p=0.027) regardless of concomitant immunomodulator or corticosteroid therapy7. There are several factors associated with advanced age that may contribute to this. These include aging of the immune system (immunosenesence) and greater comorbidity including cardiopulmonary disease that may render them more susceptible to both developing an infection and the consequence thereof44, 45. Interestingly, the relative risk of infection was higher in older IBD patients compared to RA in our meta-analysis (OR 3.48 vs. 1.87, p=0.09) suggesting that there may be disease specific effects. The dose of biologic use in IBD patients may be higher, and more frequently in combination with a higher dose of immunomodulator treatment which could contribute to this elevation in risk. Consistent with this is that individual prior studies in RA have not suggested an increase in risk of infections with biologic therapy when compared to non-users37, 38, 40.

Older age is also a well-recognized risk factor for the development of cancers. Individual studies in IBD and RA have demonstrated this association. In a large prospective cohort study among Crohn’s disease patients, age was independently associated with increased risk of malignancy (HR = 1.59 per 10 years)46. A similar correlation was found in a Swiss registry study with 7.1% of the older RA biologic users developing a malignancy compared with 0% in the younger age group (p<0.05)37. However, to what extent this is attributable to immunosuppression or biologic use is less certain as most of the cancer reported in these (such as breast and pancreatic cancer) are not those that have been linked to immunosuppression. In our study, we found a 3-fold increased risk for malignancy in older biologic users compared to the younger age group but no increase in risk compared with older non-biologic users suggesting that rather than a medication effect, this is a function of age. Not surprisingly, older biologic users had higher mortality than younger biologic users, but reassuringly there was no difference in death rates when compared to older non-biologic users demonstrating that biologic use itself is not linked to higher mortality (disease- or complication-related) in older patients.

There are several implications to our findings. First, while biologic use was associated with greater risk of infections in older patients, this should not be an absolute deterrent to use of these medications in older patients. Their use should be done with caution and in combination with minimizing risks, particularly of preventable infections through appropriate vaccination. Often in many patients, reluctance to use biologics results in under-treatment of their disease resulting in functional impairment, or in prolonged or frequent use of corticosteroids47 which have been consistently associated with greater adverse effects including risk of infections44 and mortality45. Indeed, in a study of 393 IBD patients over 65 years old showed that only 3% of the older subjects were receiving biological therapy as maintenance therapy even though 32% of the subjects were receiving long-term corticosteroids (defined as >6 months of continuous use)47.

We readily acknowledge several limitations to our study. First, as in many meta-analyses, there was heterogeneity between the studies, particularly for infections. There are potential contributors to this including varying definitions of control population, small sample size of individuals studies, and differing study outcomes. Second, as many included studies were retrospective, there may have been outcomes that were missed. Third, we did not have data on comorbidities which may influence infection risk, particularly in older patients. Fourth, there was limited data on the type of specific infections or malignancy in each of the included studies and consequently we were unable to quantify rates or increased risk for specific infections other than pneumonia. Due to paucity of data in the included studies, we were also not able to assess the impact of combination therapy with an immunomodulator, or concomitant use of corticosteroids on infection risk in older IBD patients. Prior studies have shown both these variables to impact infection rates in patients with IBD when combined with biologic therapy. Prospective studies with detailed time-varying medication exposure information is essential to robustly examine this. Finally, the sizeable majority of included studies examined patients with RA. Due to disease-specific dosing and combinations as well as impact on infection risk, there is a need for larger studies in other IMDs including IBD to provide more generalizable estimates.

In conclusion, in this meta-analysis, we demonstrate an increased risk of infections in older IMD patients on biologic therapy compared to both younger biologic users and older nonbiologic users. There is an important need for prospective studies with longer-term follow up in older patients to robustly inform clinical practice and improve patient outcomes in this vulnerable patient population.

Supplementary Material

What You Need to Know.

Background

Whether older biologic users are of increased risk to develop infections and malignancy compared to younger biologic users and older non-biologic users with an IMD is unknown.

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we quantify the risk of infection and malignancy in older biologic users and demonstrated an increased risk compared to older non-users and younger patients.

Implications for patient care

Biologic therapy in older patients should be done with caution and in combination with minimizing risks, particularly of preventable infections through appropriate vaccination.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: Dr. Ananthakrishnan has served on advisory boards for Abbvie, Takeda, and Merck. He is supported by research funding from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and Pfizer.

Abbreviations:

- IMD

Immune-Mediated Disease

- IBD

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- CD

Crohn’s Disease

- UC

Ulcerative Colitis

- RA

Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Ps

Psoriasis

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dhingra R, Vasan RS. Age as a risk factor. Med Clin North Am 2012;96:87–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Diabetes Fact Sheet: General Information and National Estimates on Diabetes in the United States. Atlanta, Georgia, US: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.US cancer statistics: 1999 – 2009 incidence and mortality web-based report. Volume http://www.cdc.gov/uscs. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mangoni AA, Jackson SH. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2004;57:6–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel CA, Hur C, Korzenik JR, et al. Risks and benefits of infliximab for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:1017–24; quiz 976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahl SL, Samuelson CO, Williams HJ, et al. Second-line antirheumatic drugs in the elderly with rheumatoid arthritis: a post hoc analysis of three controlled trials. Pharmacotherapy 1990;10:79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lobaton T, Ferrante M, Rutgeerts P, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-TNF therapy in elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:441–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desai A, Zator ZA, de Silva P, et al. Older age is associated with higher rate of discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:309–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filippini M, Bazzani C, Zingarelli S, et al. Anti-TNF α agents in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A study of a group of 105 over sixty five years old patients. Reumatismo 2008;60:41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells GA, Shea B., O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysis. Volume 2018, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health 2014;72:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koller MD, Aletaha D, Funovits J, et al. Response of elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis to methotrexate or TNF inhibitors compared with younger patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:1575–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radovits BJ, Kievit W, Fransen J, et al. Influence of age on the outcome of antitumour necrosis factor alpha therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1470–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi M, Umezawa Y, Fukuchi O, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab treatment in elderly patients with psoriasis. J Dermatol 2014;41:974–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garber C, Plotnikova N, Au SC, et al. Biologic and Conventional Systemic Therapies Show Similar Safety and Efficacy in Elderly and Adult Patients With Moderate to Severe Psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol 2015;14:846–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikari Y, Miwa Y, Yajima N. The association between elderly rheumatoid arthritis patients using biologics and adverse events: Retrospective cohort study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2017;76:801. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee WS, Azmi N, Ng RT, et al. Fatal infections in older patients with inflammatory bowel disease on anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Intest Res 2017;15:524–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Momose M, Asahina A, Hayashi M, et al. Biologic treatments for elderly patients with psoriasis. J Dermatol 2017;44:1020–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esposito M, Giunta A, Mazzotta A, et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha agents, etanercept and adalimumab, in elderly patients affected by psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: an observational long-term study. Dermatology 2012;225:312–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ricceri F, Bardazzi F, Chiricozzi A, et al. Elderly psoriatic patients under biological therapies: an Italian experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiricozzi A, Pavlidis A, Dattola A, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in psoriatic patients over the age of 65. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2016;15:1459–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costa L, Lubrano E, Ramonda R, et al. Elderly psoriatic arthritis patients on TNF-alpha blockers: results of an Italian multicenter study on minimal disease activity and drug discontinuation rate. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:1797–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe T, Kojima T, Takahashi N, et al. Tendency to choose first biologic agent therapy of rheumatoid arthritis in the elderly: Results from Japanese multicenter registry. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2017;76:1195. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jimenez MDMR, Molina OG, Carmona JM, et al. Study of effectiveness and safety of adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis. European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 2017;24:A241. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tesser J, Kafka S, DeHoratius RJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of intravenous golimumab plus methotrexate in patients 65 years and younger and those greater than 65 years of age-a post-hoc analysis. Arthritis and Rheumatology 2016;68:819–820. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ortega TL, Vermeire S, Ballet V, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-TNF therapy in elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2014;146:S-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah A, Deamude M, Mech C, et al. A retrospective study to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and drug survival of etanercept in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Rheumatology 2013;40:959. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhushan A, Pardi DS, Loftus EV, et al. Age is not associated with adverse events from biologic therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2010;138:S62. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller B, Crooks B, Garr W, et al. Biological therapy in elderly onset IBD: Sense, science and sensibility. Gut 2017;66:A249. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernardes C, Russo P, Carvalho D, et al. Safety profile of anti-TNF alpha therapy in the elderly-a comparative study. United European Gastroenterology Journal 2016;4:A456. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen H, Lipka S, Katz S. Increased hospitalizations in elderly with inflammatory bowel disease on anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy but not increased infections: a community practice experience. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:898–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cottone M, Kohn A, Daperno M, et al. Advanced age is an independent risk factor for severe infections and mortality in patients given anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:30–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murota A, Kaneko Y, Yamaoka K, et al. Safety of Biologic Agents in Elderly Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Rheumatol 2016;43:1984–1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho SK, Sung YK, Kim D, et al. Drug retention and safety of TNF inhibitors in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17:333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bathon JM, Fleischmann RM, Van der Heijde D, et al. Safety and efficacy of etanercept treatment in elderly subjects with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2006;33:234–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Genevay S, Finckh A, Ciurea A, et al. Tolerance and effectiveness of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapies in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:679–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Filippini M, Bazzani C, Zingarelli S, et al. [Anti-TNFalpha agents in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a study of a group of 105 over sixty five years old patients]. Reumatismo 2008;60:41–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galloway JB, Hyrich KL, Mercer LK, et al. Anti-TNF therapy is associated with an increased risk of serious infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis especially in the first 6 months of treatment: updated results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register with special emphasis on risks in the elderly. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:124–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schneeweiss S, Setoguchi S, Weinblatt ME, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy and the risk of serious bacterial infections in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:1754–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piaserico S, Conti A, Lo Console F, et al. Efficacy and safety of systemic treatments for psoriasis in elderly patients. Acta Derm Venereol 2014;94:293–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Der Vliet QM, Van Der Aalst KS, Ten Thije JJ, et al. Advanced age is not associated with lower safety and efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2015;148:S236. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maia L, Lago P, Rodrigues A, et al. Safety of anti-TNF treatment in elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease. United European Gastroenterology Journal 2017;5:A297–A298. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toruner M, Loftus EV Jr.,Harmsen WS, et al. Risk factors for opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2008;134:929–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Serious infection and mortality in patients with Crohn’s disease: more than 5 years of follow-up in the TREAT registry. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1409–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Drug therapies and the risk of malignancy in Crohn’s disease: results from the TREAT Registry. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:212–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Juneja M, Baidoo L, Schwartz MB, et al. Geriatric inflammatory bowel disease: phenotypic presentation, treatment patterns, nutritional status, outcomes, and comorbidity. Dig Dis Sci 2012;57:2408–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.