Abstract

Background

Carpal tunnel release (CTR) has traditionally been performed through an open approach, although in recent years endoscopic CTR has gained in popularity.

Questions/Purposes

We sought to assess whether a difference exists between the rates of nerve repair surgery following open versus endoscopic CTR in New York State (NYS).

Methods

Patients undergoing endoscopic and open CTR from 1997 to 2013 were identified from the Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) database from the NYS Department of Health using Current Procedural Terminology, 4th Revision (CPT-4) codes 29848 and 64721, respectively. The primary outcome measure was subsequent nerve repair surgery (as identified using CPT-4 codes 64831–64837, 64856, 64857, 64859, 64872, 64874, and 64876). Other variables analyzed included patient age, sex, payer, and surgery year.

Results

There were 294,616 CTRs performed in NYS from 1997 to 2013. While the incidence of open CTR remained higher than endoscopic CTR, the proportion of endoscopic CTR steadily increased, from 16% (2984/19,089) in 2007 to 25% (5594/22,271) in 2013. For the 134,143 patients having a single CTR, the rate of subsequent nerve repair was significantly higher following endoscopic CTR (0.09%) compared to open CTR (0.04%). The Cox model showed that factors significantly associated with a higher risk of subsequent nerve repair surgery were endoscopic CTR and younger age.

Conclusions

Endoscopic CTR has been increasingly performed in NYS and associated with a higher rate of subsequent nerve repair. This rate likely underestimates the incidence of nerve injuries because it only captures those patients who had subsequent surgery. While this catastrophic complication remains rare, further investigation is warranted, given the rise of endoscopic CTR in the setting of equivalent outcomes, but favorable reimbursement, versus open CTR.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11420-018-9637-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: carpal tunnel release, nerve injury, carpal tunnel syndrome, median nerve, nerve repair

Introduction

The incidence of carpal tunnel release (CTR) in the USA grew from 360,000 in 1996 to 577,000 in 2006 [2]. CTR has traditionally been performed through an open approach, although in recent years, endoscopic CTR has gained in popularity.

Numerous clinical studies have compared open versus endoscopic CTR. A 2014 Cochrane review of 28 randomized, controlled studies and 2856 surgeries concluded that open and endoscopic CTR were equally effective in relieving symptoms and curing carpal tunnel syndrome [7]. However, endoscopic CTR was more frequently associated with transient nerve-related complications, and open CTR was more frequently associated with wound complications. Similarly, two meta-analyses of randomized, controlled studies comparing open and endoscopic CTR concluded that while long-term clinical outcomes were similar, endoscopic CTR was associated with an increased risk of nerve injury (mostly transient neurapraxia) [4, 8]. The risk for iatrogenic nerve injury during endoscopic CTR has also been reported in two cadaveric studies [3, 5]. Of note, endoscopic CTR has a higher reimbursement (29% more relative value units) than open CTR.

Given the equivalent efficacy of open and endoscopic CTR in recently published studies and the potential increased rate of iatrogenic nerve injury during endoscopic CTR, which is a catastrophic complication of CTR, we aimed to determine (1) the recent trends in volume of open and endoscopic CTR in New York State (NYS) and (2) whether a difference existed between the subsequent rates of nerve repair following open versus endoscopic CTR.

Materials and Methods

The Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) database from the NYS Department of Health was queried to identify all endoscopic and open CTRs performed in NYS between 1997 and 2013 using CPT-4 (Current Procedural Terminology, 4th Revision) codes 29848 and 64721, respectively. The SPARCS database is a census of all non-federal hospital admissions and ambulatory procedures in NYS.

Unique encrypted patient identifiers allow subsequent hospitalization(s) and/or ambulatory procedure(s) to be tracked throughout NYS regardless of insurance status, provider, or institution. Patient age, sex, and payer were recorded. Ambulatory procedure records through 2014 were searched for subsequent nerve repair surgery (CPT-4 codes 64831–64837, 64856, 64857, 64859, 64872, 64874, and 64876) to provide a minimum of 1 year post-CTR surveillance. Patients with multiple CTRs, non-NYS residents, and those with a traumatic hand injury (after CTR and before nerve repair surgery) were excluded. The association between subsequent nerve repair and CTR type was evaluated using a multivariable Cox proportional-hazards regression model, adjusting by patient age, sex, and payer.

This research was approved by the Hospital for Special Surgery Institutional Review Board (No. 2016-166).

Results

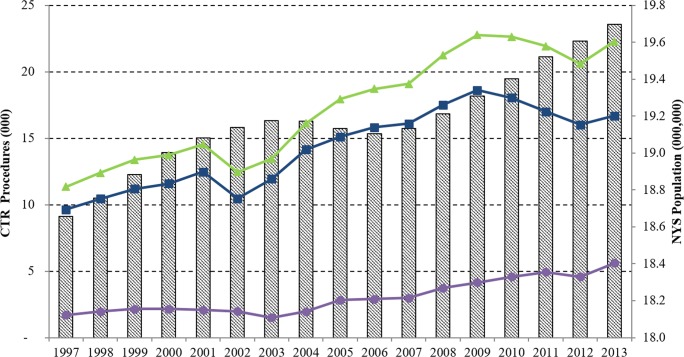

There were 294,616 CTRs performed in NYS between 1997 and 2013. While the incidence of open CTR remained higher than endoscopic CTR throughout the study period, the proportion of endoscopic CTR steadily increased since 2008 (Fig. 1). In 2007, 16% (2984/19,089) of CTRs performed in NYS were endoscopic, compared to 25% (5594/22,271) in 2013.

Fig. 1.

Line graphs show the annual carpal tunnel release (CTR) volume for open CTR (blue), endoscopic CTR (purple), and both procedures combined (green) in thousands (left axis) from 1997 to 2013. Bars represent the New York State (NYS) population for each year in millions (right axis).

After excluding non-NYS residents and patients with multiple CTRs, 134,143 patients had a single CTR during the study period. Of these, 26 had subsequent nerve repair surgery in the absence of additional upper-extremity surgery and/or traumatic upper-extremity injury. The rate of subsequent nerve repair was significantly higher following endoscopic CTR (0.09%) versus open CTR (0.04%; p 0.01). Endoscopic CTR had a significantly higher risk of subsequent nerve repair surgery versus open CTR (hazard ratio, 2.40; 95% confidence interval, 1.02–5.27). Subsequent nerve repair surgery risk also significantly decreased with each additional unit year of age (hazard ratio, 0.97; 95% confidence interval, 0.94–1.00). There was no correlation between subsequent nerve repair surgery risk and patient sex or payer.

Discussion

Endoscopic CTR volume relative to open CTR has steadily increased in NYS since 2008. The risk of subsequent nerve repair after endoscopic CTR, while rare, is 2.40 times more likely than after open CTR. This hazard ratio likely underestimates the overall rate of nerve-related complications, as we only captured patients who had subsequent surgery and not those treated non-operatively.

Several meta-analyses have reported a 2.38 to 2.84 relative risk of nerve-related complications following endoscopic CTR versus open CTR [4, 7, 8]. These rates may be underestimations, since many studies include higher volume, more experienced surgeons who may have lower risk than average endoscopic surgeons. In addition, in previous studies, patients may be lost to follow-up and not captured if they have subsequent surgery performed by a different surgeon than the index procedure. On the other hand, this study utilizes the SPARCS database which overcomes these limitations by providing statewide, population-based, longitudinal data. In this study, the magnitude of increased risk of nerve repair surgery following endoscopic CTR (2.40) was consistent with the relative risk of nerve-related complications following endoscopic (versus open) CTR in recent meta-analyses (2.38 to 2.84). However, the nerve-related complication being evaluated in this study—nerve laceration requiring surgical repair—though rare, is catastrophic, in comparison to the frequently transient neurapraxia cited in previous studies [4, 7, 8]. The SPARCS database allows us to identify this complication by longitudinally tracking patients in NYS.

In this study, a decreased risk (hazard ratio, 0.97) of subsequent nerve repair surgery was observed in patients of older age. Although endoscopic CTR patients were significantly younger than open CTR patients, the association of subsequent nerve repair surgery with patient age was an independent risk factor based on multivariable analysis. Another potential explanation is that younger patients may be more likely to have anatomic abnormalities that cause carpal tunnel syndrome at an earlier age, as well as place the median nerve (or its branches) at risk during CTR surgery.

This study has several limitations. First, the SPARCS database and this study’s conclusions are dependent on accurate procedural coding. Both nerve repair surgeries and potential intervening traumatic upper-extremity injuries (which were excluded) were examined based on CPT code. Second, the SPARCS database is limited to NYS. Thus, if a CTR patient had subsequent surgery in another state, it would not be captured by this database. Furthermore, it is possible that either endoscopic CTR trends and/or rates of subsequent nerve repair vary in other geographic locations. Finally, although patients with revision CTRs were excluded (as defined by multiple CTRs during the study period), it is possible that patients had an index CTR prior to 1997 and thus not detected in the database. These patients would be more likely to undergo open CTR and potentially more likely to have a complication due to the revision surgery setting.

The increasing proportion of patients undergoing endoscopic CTR is cause for concern. If the current trends remain constant, we expect that the majority of CTRs will be endoscopic by 2024 in NYS. The small but significantly increased risk of nerve lacerations (as detected by nerve repair surgeries) following endoscopic CTR could result in a substantial number of avoidable nerve injuries. These findings warrant further investigation, given the rising rate of endoscopic CTR in the setting of equivalent clinical outcomes, but favorable reimbursement, versus open CTR.

A recent meta-analysis has suggested no difference in major complication rates with endoscopic versus open CTR in the setting of equivalent long-term clinical outcomes [6]. The authors hypothesized that recent literature, in comparison to older literature, may demonstrate a lower complication rate secondary to a learning curve in endoscopic CTR technique. In another study evaluating outcomes of a novice endoscopic CTR surgeon, a learning curve (as defined by the number of cases requiring conversion to open CTR) was present, although no major neurovascular complications were reported [1]. Taken together, two relevant unanswered questions from the SPARCS database are whether surgeon experience and/or year of surgery correlated with the risk of iatrogenic nerve injury for endoscopic and/or open CTR. Given the findings from this study, we believe that the incidence of nerve laceration requiring surgical repair following endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release should be closely evaluated in a large-scale, prospective, registry-style clinical study given the catastrophic, nature of this complication.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Samir K. Trehan, MD, Stephen Lyman, PhD, Yile Ge, MS, Huong T. Do, MA, and Aaron Daluiski, MD, declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (grant number UL1-RR024996).

Human/Animal Rights

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was waived from all patients for being included in this study.

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Footnotes

Level of Evidence: Level III, Prognostic Study

References

- 1.Beck JD, Deegan JH, Rhoades D, Klena JC. Results of endoscopic carpal tunnel release relative to surgeon experience with the Agee technique. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:61–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fajardo M, Kim SH, Szabo RM. Incidence of carpal tunnel release: trends and implications within the United States ambulatory care setting. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:1599–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowland EB, Kleinert JM. Endoscopic carpal-tunnel release in cadavera. An investigation of the results of twelve surgeons with this training model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:266–268. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199402000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sayegh ET, Strauch RJ. Open versus endoscopic carpal tunnel release: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:1120–1132. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3835-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz JT, Waters PM, Simmons BP. Endoscopic carpal tunnel release: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:209–213. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(05)80376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasiliadis HS, Nikolakopoulou A, Shrier I, Lunn MP, Brassington R, Scholten RJ, Salanti G. Endoscopic and open release similarly safe for the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasiliadis HS, Georgoulas P, Shrier I, Salanti G, Scholten RJ. Endoscopic release for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD008265. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008265.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuo D, Zhou Z, Wang H, Liao Y, Zheng L, Hua Y, Cai Z. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release for idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res. 2015;10:12,014-0148-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)