Abstract

Identifying new causes of permanent neonatal diabetes (PNDM) (diagnosis <6 months) provides important insights into β-cell biology. Patients with Down syndrome (DS) resulting from trisomy 21 are four times more likely to have childhood diabetes with an intermediate HLA association. It is not known whether DS can cause PNDM. We found that trisomy 21 was seven times more likely in our PNDM cohort than in the population (13 of 1,522 = 85 of 10,000 observed vs. 12.6 of 10,000 expected) and none of the 13 DS-PNDM patients had a mutation in the known PNDM genes that explained 82.9% of non-DS PNDM. Islet autoantibodies were present in 4 of 9 DS-PNDM patients, but DS-PNDM was not associated with polygenic susceptibility to type 1 diabetes (T1D). We conclude that trisomy 21 is a cause of autoimmune PNDM that is not HLA associated. We propose that autoimmune diabetes in DS is heterogeneous and includes coincidental T1D that is HLA associated and diabetes caused by trisomy 21 that is not HLA associated.

Introduction

Permanent neonatal diabetes (PNDM) is diagnosed before the age of 6 months, and a genetic diagnosis is possible for >82% of cases (1). Twenty-four causative PNDM genes have been identified (1–4), and four of these cause monogenic autoimmune PNDM that results from destruction of the β-cells very early in life (FOXP3, IL2RA, LRBA, and STAT3). Identifying novel causes of autoimmune neonatal diabetes can provide key insights into the development of autoimmunity and can provide new targets for therapeutic intervention.

Down syndrome (DS) is caused by trisomy of chromosome 21 and has an incidence of 1:700 to 1:1,100 live births (5). Large studies have shown childhood-onset autoimmune diabetes is four times more common in DS than in the general population and has an intermediate HLA association (6). There have been three reported cases of DS with diabetes diagnosed before 6 months (DS-PNDM) (7,8). However, it is not known whether DS was the cause of PNDM or a coincidental finding in these patients. The aim of our study was to use our large international cohort of PNDM patients to assess whether DS can aetiologically cause PNDM. We assessed clinical phenotype, islet autoantibodies, and polygenic risk of T1D in patients with monogenic PNDM and DS-PNDM.

Research Design and Methods

Study Population

We defined PNDM as diabetes diagnosed before the age of 6 months, which is treated with continual insulin treatment. We studied 1,522 DNA samples from two international collections of PNDM patients, 1,360 recruited in Exeter and 162 recruited in Chicago. These either had a confirmed monogenic etiology (82.9% [n = 1,262]) or had been tested (and were negative) for all 24 known genes (17.1% [n = 260]). Clinical information was provided by the referring physician via a comprehensive referral form. This includes a section for the reporting of extra pancreatic clinical features.

Genetic Testing

Testing of the Known Genes

All individuals diagnosed in the first 6 months of life were tested for mutations either by rapid Sanger sequencing of ABCC8, KCNJ11, and INS or, if no mutation was identified, via targeted DNA sequencing through next-generation sequencing (tNGS) of all 24 genes (1–4,9). This assay can detect single nucleotide variants, insertion-deletions, copy number variation, and structural variation (9).

Exclusion of Trisomy 21

We used SavvyCNV (10,11) to screen for trisomy 21 in the PNDM and autoimmune-PNDM cohorts where tNGS was undertaken (n = 445). This uses off-target reads from tNGS data to detect large copy number and structural variants.

Type 1 Diabetes Genetic Risk Score

The Type 1 Diabetes genetic risk score (T1D-GRS) was generated where there was sufficient DNA as previously described (12). Briefly, we genotyped single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) tagging the top 10 risk alleles for type 1 diabetes (T1D) and summed their log-transformed odds ratios before dividing by the total number of alleles to obtain a numeric score. None of the SNPs used are on chromosome 21. We used T1D-GRS from 1963 gold standard T1D individuals (all diagnosed <17 years) from the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium as a representative sample for polygenic T1D (13). As part of the score generation, SNPs rs2187668 and rs7454108 were used to tag DR3 (DRB1*0301-DQA1*0501-DQB1*0201) and DR4-DQ8 (DRB1*04-DQA1*0301-DQB1*0302) alleles. These SNPs have been shown to be 98.6% sensitive and 99.7% specific for tagging DR3/DQ4-DQ8 (14). We used rs3129889 to tag HLA DRB1*15 (15).

The T1D-GRS was available for 13 patients with DS-PNDM, 458 individuals with a confirmed nonautoimmune monogenic etiology (non-DS PNDM), and 40 individuals with a monogenic cause of autoimmune PNDM (autoimmune non-DS PNDM). There was no difference in clinical features between individuals with or without T1D-GRS.

Islet Autoantibody Testing

Islet autoantibodies GADA, IA-2A, and/or ZnT8A were measured either by local assays or from plasma on the sample received at the Exeter Clinical Laboratory using an automated ELISA-based assay as previously described (16). We used >97.5th centile of control subjects (n = 1,559) to define positivity for autoantibodies.

Statistical Analysis

The Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare continuous variables, and the Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Statistical analysis was undertaken in Stata14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Genetic Beta Cell Research Bank, Exeter, U.K., and The University of Chicago. Ethics approval was provided by the North Wales Research Ethics Committee, U.K. (Integrated Research Application System [IRAS] project identification no. 231760) and The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board (institutional review board no. 6858, identification no. 15617B).

Results

Trisomy 21 Is Enriched in PNDM

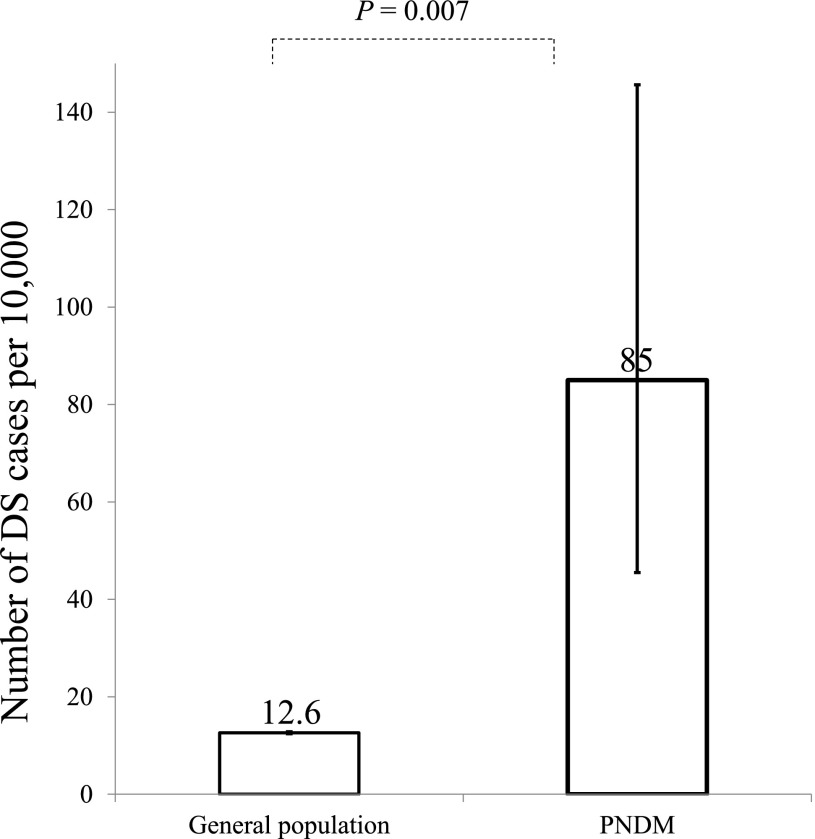

To assess whether DS is enriched in our PNDM cohort, we compared the observed frequency in the PNDM cohort with the expected frequency based on the population prevalence. Using clinical data obtained at referral, we identified 13 of 1,522 (0.9%) individuals with DS-PNDM in our international PNDM cohort. In all 13 individuals, trisomy 21 was confirmed by karyotyping and analysis of tNGS data using SavvyCNV. We did not detect Trisomy 21 in any individual without a clinical diagnosis of DS. The observed frequency in our cohort was therefore 85 of 10,000 (95% CI 45–146), which is 6.7-fold higher than the expected population frequency of 12.6 of 10,000 (95% CI 12.4–12.8) (P = 0.007) (5) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

DS is enriched in our PNDM cohort. DS has a population prevalence of 12.6 of 10,000 (95% CI 12.4–12.8), whereas in our cohort of 1,522 patients with neonatal diabetes we have 13 cases, equivalent to 85 of 10,000 (40.4–144.3); P = 0.007.

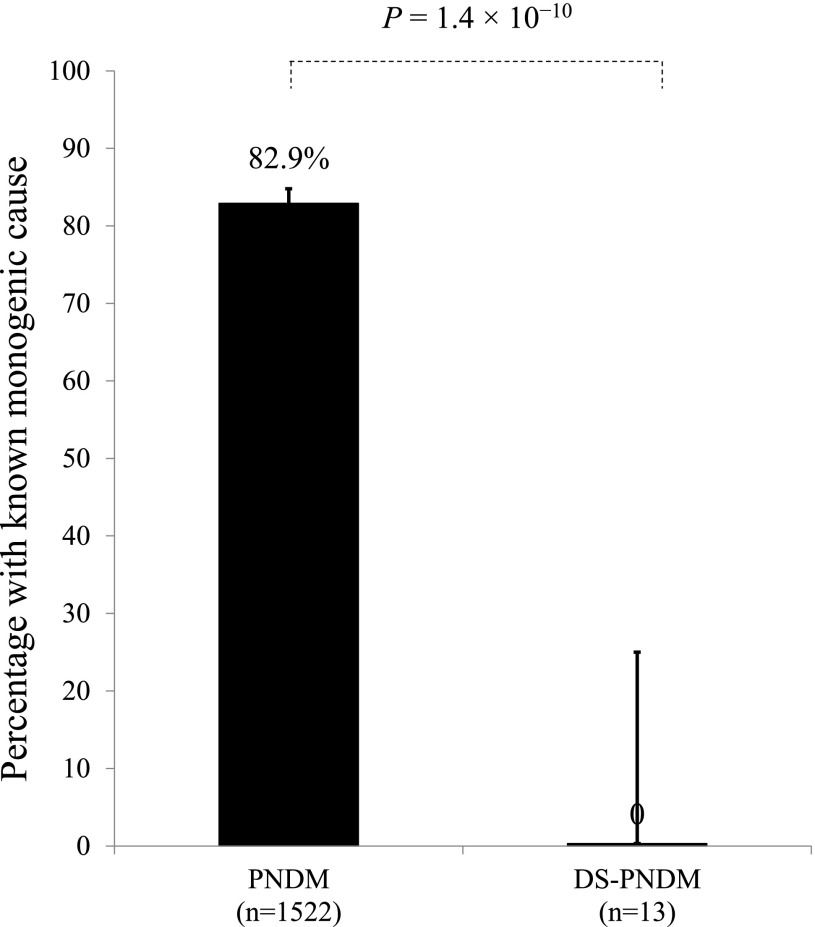

Patients With DS-PNDM Do Not Have Mutations in Any of the 24 Genes Known to Cause Monogenic PNDM

We next assessed the presence of known monogenic etiology in patients with DS-PNDM. None of the 13 DS-PNDM individuals had pathogenic variants in the 24 known PNDM genes. In contrast, 1,262 of 1,522 (82.9%) of the non-DS PNDM had a monogenic etiology (Fig. 2) (P = 1.4 × 10−10). Taken together, these two results strongly support trisomy 21 as a cause of PNDM.

Figure 2.

DS-PNDM is not caused by other known neonatal diabetes genes. The 24 known neonatal diabetes genes account for 82.9% of cases, while none of the 13 DS-PNDM case subjects had a mutation in a known gene (P = 1.4 × 10−10).

Islet Autoimmunity Is Common in DS-PNDM

To further assess the underlying etiology of DS-PNDM, we compared the clinical characteristics of the DS-PNDM patients with the PNDM cohort with a nonautoimmune monogenic cause (non-DS PNDM) (n = 458) or monogenic autoimmunity (autoimmune non-DS PNDM) (n = 40). We found that 44% (4 of 9) of the DS-PNDM individuals were positive for one autoantibody (all GADA and none IA2A or ZnT8A) with time from diabetes diagnosis to testing ranging from 4 months to 10 years (Table 1). This was similar to the autoimmune non-DS PNDM (46% [13 of 28]; P = 1.0) but higher than the non-DS PNDM (21 of 293 [7%]; P = 0.004) (Table 2). This supports an autoimmune etiology in DS-PNDM.

Table 1.

Features of the DS-PNDM cohort

| Patient | Sex | Ethnicity | Maternal age at birth (years) | Patient current age | Birth weight z scorea | Age at diabetes diagnosis | Treatment | HbA1c, % (mmol/L)b | Autoantibodies tested | Autoantibody status | Diabetes duration at antibody testing | T1D-GRS (centile of T1D)c | HLA DR genotyped | Other conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | Caucasian | ND | 23 years | −0.79 | 7 weeks | Insulin | 9.5 (80) | ND | ND | NA | 0.37 (0.1) | DRB1*15/X | Hypothyroidism, ASD |

| 2 | Female | Hispanic | ND | 14 years | −3.99 | 1 week | Insulin | 8.1 (65) | ND | ND | NA | 0.70 (53.5) | DR4/DR4 | Hypothyroidism, hearing and vision problems |

| 3 | Male | Caucasian | 33 | 1 years | −1.02 | 2 days | Insulin | ND | GADA, IA-2A, ZnT8A | Negative | 1 week | 0.69 (48.2) | DR3/DR3 | Tetralogy of Fallot, macroglossia |

| 4 | Male | Caucasian | ND | 28 years | ND | 3 months | Insulin | 8.5 (69) | GADA, IA-2A, ZnT8A | GADA positive | 10 years | 0.52 (2.5) | X/X | Seizures |

| 5 | Male | Arabic | 37 | 1 years | ND | 4 months | Insulin | 8.8 (73) | GADA, IA-2A, ZnT8A | GADA positive | 4 months | 0.66 (33.9) | DR3/DR3 | — |

| 6 | Male | Hispanic | 40 | 9 months | −2.65 | 2 weeks | Insulin | 5.7 (39) | GADA, IA-2A, ZnT8A | Negative | 2 months | 0.64 (25.4) | DR4/X | Subclinical hypothyroidism, macroglossia, cardiac malformation |

| 7 | Male | Mixed (East Asian/ Caucasian) | 43 | 20 years | 0.80 | 3 days | Insulin | 8.8 (73) | GADA | GADA positive | 8 years | 0.63 (20.6) | DR3/X | Hypothyroidism, celiac disease exocrine insufficiency |

| 8 | Male | Arabic | ND | 9 years | −1.23 | 8 weeks | Insulin | 9.3 (78) | GADA, IA-2A | GADA positive | 5 years | 0.37 (0.1) | DRB1*15/X | Macroglossia |

| 9 | Female | Turkish | ND | 15 years | ND | 3 weeks | Insulin | 8.1 (65) | GADA, IA-2A | Negative | 1 day | 0.61 (14.3) | DR3/X | Hypothyroidism |

| 10 | Female | Hispanic | ND | Died aged 7 months | −3.30 | 3 days | Insulin | 6.6 (49) | ND | ND | NA | 0.49 (0.9) | DR4/DRB1*15 | — |

| 11 | Male | Caucasian | 35 | 6 years | −0.84 | 1 day | Insulin | 6.6 (49) | GADA, IA-2A, ZnT8A | Negative | 5 months | 0.48 (0.8) | DR3/DRB1*15 | Transient hypothyroidism, VSD |

| 12 | Male | Caucasian | ND | 17 years | 0.19 | 18 days | Insulin | 9.8 (84) | ND | ND | ND | 0.69 (48.2) | DR4/X | Seizures, hypothyroidism, frequent infections (low IgM), hepatic abscess |

| 13 | Male | Caucasian | ND | 1 year | −1.85 | Birth | Insulin | 7.0 (53) | GADA, ZnT8A | Negative | ND | 0.68 (44.5) | DR4/DR4 | Hyperthyroidism, bowel obstruction, speech and vision problems |

ASD, atrial septal defect; NA, not applicable; ND, no data; VSD, ventral septal defect.

az score adjusted for sex and gestational age.

bLatest HbA1c reported by clinician.

cT1D-GRS based on top 10 risk alleles; centile of T1D refers to the centile of the T1D control population that this score corresponds with.

dX denotes any HLA DR haplotype other than DR3, DR4, or DRB1*15.

Table 2.

Comparison of DS-PNDM with non-DS PNDM and autoimmune non-DS PNDM

| Characteristic | DS-PNDM (n = 13) | Non-DS PNDM (n = 458) | Autoimmune non-DS PNDM (n = 40) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diabetes diagnosis (weeks) | 2.3 (0.4, 7.5) | 7 (3, 12) | 4 (1, 13.5) |

| Female sex | 23% (3 of 13) | 43% (197 of 458) | 12.5% (5 of 40)* |

| Birth weight z score† | −1.23 (−2.65, −0.84) [n = 10] | −1.74 (−2.55, −0.82) [n = 378] | −0.39 (−1.06, 0.29) [n = 30]‡ |

| Positive for ≥1 autoantibodies§ | 4 of 9 (44%) | 21 of 293 (7%)|| | 13 of 28 (46%) |

| T1D-GRS | 0.61 (0.49, 0.66) | 0.55 (0.51, 0.61) | 0.57 (0.52, 0.62) |

T1D-GRS: centiles based on control subjects with T1D. Age at diabetes diagnosis, birth weight z score, and T1D-GRS are given as median (interquartile range). Other than where indicated, data were similar for all cohorts (P > 0.1).

*Low due to males with IPEX (immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked) syndrome (n = 25/40).

†Adjusted for sex and gestational age.

‡DS-PNDM vs. autoimmune non-DS PNDM, P = 0.02.

§One or more positive titer for GADA, IA-2A, or ZnT8A.

||DS-PNDM vs. non-DS PNDM, P = 0.006.

The median age of onset of diabetes was similar in all three groups (Table 2). The birth weight of the DS-PNDM cohort was low (−1.23 SDs). This was similar to that in the non-DS PNDM individuals (−1.74 SDs; P = 0.87) and lower than in those with autoimmune non-DS PNDM (−0.39 SDs; P = 0.02). Full clinical information for each subject with DS-PNDM and diabetes is given in Table 1.

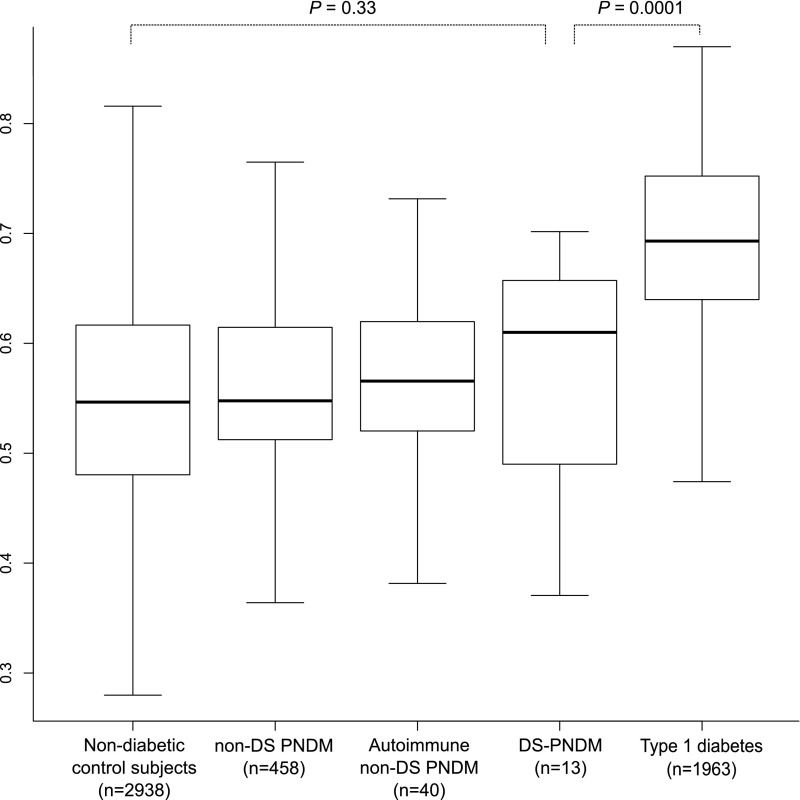

DS-PNDM Is Genetically Distinct From Type 1 Diabetes

To further investigate the etiology of autoimmune diabetes in DS-PNDM, we assessed polygenic risk for T1D (T1D-GRS) in DS-PNDM and compared it with both T1D and monogenic PNDM. T1D-GRS in individuals with DS-PNDM was similar to that in control subjects without diabetes (Fig. 3) (median T1D-GRS 0.61 vs. 0.55; P = 0.33), non-DS PNDM (0.61 vs. 0.55; P = 0.48), and autoimmune non-DS PNDM (0.61 vs. 0.57; P = 0.65) but lower than the T1D control group (0.61 vs. 0.69; P = 0.0001). While 10 of 13 individuals with DS-PNDM carried a copy of either DR3 or DR4, none had the highest-risk HLA DR3/DR4 genotype compared with 34% (666 of 1,963) of T1D control subjects (P = 0.006) (Table 1). Furthermore, 4 of 13 (36%) DS-PNDM subjects carried the HLA DRB1*15 allele, which is dominantly protective against T1D, compared with 2% (40 of 1,963) of T1D control subjects (P = 0.0001). This is similar to control subjects without diabetes who carry the protective HLA DRB1*15 allele (1,643 of 2,938, P = 0.27). These data suggest that DS-PNDM is not HLA associated and is therefore unlikely to be very-early-onset polygenic T1D.

Figure 3.

The T1D-GRS in DS-PNDM. Patients with DS-PNDM (n = 13) had a lower score than T1D control subjects (n = 1,963), and their scores were similar to those with the known monogenic forms of non-DS PNDM and autoimmune non-DS PNDM (n = 458 and n = 40, respectively; P = 0.52) and control subjects without diabetes (n = 2,938; P = 0.33). The central line within the box represents the median, and the upper and lower limits of the box represent the interquartile range. The whiskers are the most extreme values within 1.5× the interquartile range from the first and second quartiles.

Discussion

Our study identifies trisomy 21 as a rare cause of autoimmune PNDM. We have shown that DS is sevenfold enriched in our PNDM cohort and that none of the DS-PNDM individuals have a mutation in any of the 24 known PNDM genes. The antibody data support an autoimmune etiology in DS-PNDM that is not associated with increased polygenic susceptibility to T1D. DS-PNDM is rare in people with DS, suggesting that trisomy 21 is a low-penetrance cause of PNDM.

We found that PNDM caused by trisomy 21 can be linked to β-cell autoimmunity, as shown by the presence of islet antibodies in four of nine cases (17). Islet antibodies are seen in HLA-associated T1D and also in autoimmune non-DS PNDM, which is not HLA associated (12). The proportion of patients with DS-PNDM who were autoantibody positive was similar to that in non-DS PNDM caused by monogenic autoimmunity. The islet antibodies are unlikely to be due to maternal transfer of antibodies, as measurement for 3 of the 4 GADA-positive patients was done after 9 months (18,19).

Our data suggest prenatal onset of β-cell dysfunction/destruction in DS-PNDM. We found that the birth weight of the DS-PNDM individuals was reduced (median z score −1.23), lower than the birth weight seen in DS without PNDM (z score for boys −0.47 and girls −0.07). Interestingly, the birth weight was similar to that in non–DS-PNDM patients whose lower birth weight is due to reduced insulin secretion in utero. Global immunological changes in individuals with DS have been identified including defects in T-cell regulation and thymus development that are evident in newborns (20). These data taken together suggest prenatal onset of autoimmunity and pancreatic dysfunction.

We found that individuals with DS-PNDM do not have increased polygenic risk of T1D even though they develop diabetes before 6 months of age. This is contrary to T1D in which the HLA association is increased with younger age of diagnosis (21). Furthermore, 4 of 13 (31%) individuals carry the DRB1*15 haplotype, which provides dominant protection against T1D and is very rarely seen in patients with T1D (40 of 1,963 [2%]). Two of these also carried DR3 or DR4; however, inheritance with the DRB1*15 allele nullifies the risk allele (22). The DS-PNDM cohort is of mixed ethnicities (6 Caucasian, 3 Middle Eastern, 3 Hispanic, and 1 mixed), but population stratification does not account for the difference in HLA alleles between DS-PNDM cases and T1D; the HLA DR3/DR4 diplotype is strongly predisposing and the DRB1*15 allele is strongly protective for T1D across these populations (23–25). These data support that DS-PNDM is not HLA associated.

A previous study showed that DS with diabetes had intermediate HLA association (7). The highest-risk HLA diplotype—DR3/DR4—was present in half as many DS diabetes cases compared with T1D (17% of DS diabetes, 38% of T1D, 3% of control subjects). We propose that this is explained by diabetes in DS in these studies reflecting a mixture of two subtypes of autoimmune diabetes: one caused by trisomy 21–related immune dysregulation (not HLA associated), and the other coincidental polygenic T1D (HLA associated) in which trisomy 21–related immune dysregulation is not playing as strong a role. A mixture of two aetiologies is also reflected by the observation that age of onset of diabetes in DS is biphasic, with a peak at 1 year and another at 10 years of age, the latter coinciding with non-DS T1D.

We have shown a sevenfold increase in the prevalence of diabetes before the age of 6 months in DS. Previous authors (6) have shown an increase of diabetes between 0.5 and 18 years of approximately fourfold. The difference in prevalence means patients are far less likely to get diabetes before 6 months (7 of 100,000) compared with 0.5–18 years (700 of 100,000).

A complex interaction between multiple genes on chromosome 21 may be responsible for autoimmunity in DS. The autoimmune regulator gene, AIRE, which is in the minimal region for DS on chromosome 21, regulates the ectopic expression of tissue-restricted antigens in the thymus to expose developing T cells to self-peptides; those that are strongly reactive are removed or reprogrammed (26). Mutations in AIRE cause autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1, which commonly includes endocrine autoimmunity (27). AIRE has been shown to be aberrantly expressed in individuals with DS. A study of infant (0–6 months) thymi removed during cardiac surgery found that AIRE mRNA and protein expression was elevated in DS case subjects (n = 5) versus non-DS control subjects (n = 5) (28). The mRNA expression of two genes under AIRE’s control in medullary thymocytes, INS (encoding insulin) and CHRNA1 (encoding a subunit of muscle acetylcholine receptor), was also increased. Furthermore, this study found an increased overall number of medullary thymocytes expressing AIRE, which the authors propose could be linked to an effect on thymocyte turnover; AIRE is known to promote terminal differentiation in medullary thymocytes (29,30). AIRE has multiple complex roles in thymic function (including Treg selection, antigen expression, cell differentiation, antigen presentation, and chemokine production [31]), and increased expression of AIRE was counterintuitively postulated to result in an alteration of the balance of these processes and therefore impaired thymic selection and reduced central tolerance resulting in increased autoimmunity.

Two larger studies of the DS thymus found that AIRE mRNA expression was reduced twofold in DS thymi and that genes under AIRE’s control in medullary thymocytes had reduced expression (32,33). They found that the number of medullary thymocytes positive for AIRE was also reduced. Intriguingly, Giménez-Barcons et al. (33) found that all three copies of AIRE present in DS cases were equally expressed, albeit at reduced total levels, suggesting overcompensation by transcriptional repression of all alleles. The patients in these studies were older than those in the study by Skogberg et al. (28) (2 months–12 years); therefore, a potential temporal relationship of AIRE expression in DS thymus, possibly linked to AIRE’s role in differentiation and turnover of thymocytes (29,30), could explain the difference. None of the cases were reported to have diabetes; however, 11 of 19 reported by Giménez-Barcons et al. had organ-specific autoimmunity (hypothyroidism, Graves disease, or celiac disease).

Additional genes contained in chromosome 21 have been linked to the increased incidence of autoimmune diabetes in DS. The UBASH3A gene, also on chromosome 21, has been associated (and the association replicated) with T1D and has a role in the regulation of T cells (34). UBASH3A downregulates T-cell receptor–induced NFкB signaling (35). NFкB signaling regulates multiple aspects of the innate and adaptive immune system including the expression of IL2 (36), a pleiotropic cytokine whose roles include the regulation of self-tolerance (37). Furthermore, a gene cluster containing four interferon receptors (IFNAR1, IFNAR2, IFNGR2, and IL10RB) is on chromosome 21 and it has been shown that increased interferon signaling is a hallmark of DS (38). RNA sequencing experiments showed that interferon-related factors were consistently overexpressed in DS lymphocytes compared with controls. Increased interferon signaling has been implicated in multiple autoimmune diseases, including T1D (39–42).

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of DS-PNDM. Study of additional individuals will provide further insight into the underlying mechanism of DS-PNDM. An interesting follow-up would be to look at the T1D-GRS in an older cohort of DS individuals with diabetes to assess whether genetic risk for T1D increases with older age at onset. Furthermore, we were unable to test all islet autoantibodies in all individuals close to diagnosis or perform immunophenotyping on their leukocytes. This would provide further understanding of the autoimmunity in DS-PNDM.

In conclusion, we have shown that trisomy 21 is a cause of PNDM. The underlying mechanism of the diabetes is likely to be due to autoimmunity against the β-cells. We propose that diabetes in DS is heterogeneous and consists of a subtype with diagnosis very young (including PNDM) that is autoimmune but not HLA mediated and a second type that is similar to T1D in the non-DS population and has a strong HLA association. Extended genetic testing of known monogenic diabetes genes for individuals with DS-PNDM beyond the most common forms—activating mutations in ABCC8 or KCNJ11—may not be needed.

Supplementary Material

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the referring clinicians, patients, and their families.

Funding. This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award to S.E. and A.T.H. (grant 098395/Z/12/Z); the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (grants K23 DK094866, R01 DK104942, and P30 DK020595); the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program (grant UL1 TR000430); and the American Diabetes Association (grant 1-17-JDF-008). S.E.F. has a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust/Royal Society (grant 105636/Z/14/Z). K.A.P. has a postdoctoral fellowship funded by the Wellcome Trust (110082/Z/15/Z). A.T.H. is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) senior investigator. Additional support came from the Helmsley Foundation’s Breakthrough Initiative, Diabetes Research & Wellness Foundation, University of Exeter, and the NIHR Exeter Clinical Research Facility.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. M.B.J, E.D.F, K.A.P., and A.T.H. designed the study. M.B.J. performed the genetic and statistical analysis, interpreted data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. E.D.F, S.A.W.G., L.R.L., S.E., S.E.F., and K.A.P. assisted with the interpretation of clinical information and contributed to discussion. M.N.W. performed bioinformatics analysis. M.B.J., K.A.P., and A.T.H. wrote the manuscript, which was reviewed and edited by all authors. A.T.H. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Data and Resource Availability. The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Prior Presentation. Parts of this study were presented in abstract form at the 54th Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Berlin, Germany, 1–5 October 2018.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db19-0045/-/DC1.

A complete listing of members of the International DS-PNDM Consortium can be found in Supplementary Data.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: International DS-PNDM Consortium, Miguel Angel De los Santos, Carlos Manuel Del Águila, Luis Rómulo de Lama, Oswaldo Nuñez, Eliana Manuela Chávez, Oscar Antonio Espinoza, Paola Marianella Pinto, Martha Rosario Calagua, Asma Deeb, Stephen M.P. O’Riordan, Semra Çetinkaya, Rebeka Ribicic, Gordana Stipancic, Christine Rodda, Leonard C. Harrison, Andrea Steck, Paul G. Voorhoeve, Mouza AlYahyaei, Aisha AlSinani, Hanan AlAzkawi, and Mariyam AlBadi

References

- 1.De Franco E, Flanagan SE, Houghton JAL, et al. The effect of early, comprehensive genomic testing on clinical care in neonatal diabetes: an international cohort study. Lancet 2015;386:957–963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Franco E, Flanagan SE, Yagi T, et al. Dominant ER stress-inducing WFS1 mutations underlie a genetic syndrome of neonatal/infancy-onset diabetes, congenital sensorineural deafness, and congenital cataracts. Diabetes 2017;66:2044–2053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flanagan SE, Haapaniemi E, Russell MA, et al. Activating germline mutations in STAT3 cause early-onset multi-organ autoimmune disease. Nat Genet 2014;46:812–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson MB, De Franco E, Lango Allen H, et al. Recessively inherited LRBA mutations cause autoimmunity presenting as neonatal diabetes. Diabetes 2017;66:2316–2322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Graaf G, Buckley F, Skotko BG. Estimates of the live births, natural losses, and elective terminations with Down syndrome in the United States. Am J Med Genet Part A 2015;167A:756–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergholdt R, Eising S, Nerup J, Pociot F. Increased prevalence of Down’s syndrome in individuals with type 1 diabetes in Denmark: a nationwide population-based study. Diabetologia 2006;49:1179–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aitken RJ, Mehers KL, Williams AJ, et al. Early-onset, coexisting autoimmunity and decreased HLA-mediated susceptibility are the characteristics of diabetes in Down syndrome. Diabetes Care 2013;36:1181–1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shehadeh N, Gershoni-baruch R, Etzioni A. Congenital diabetes in an infant with trisomy 21. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 1998;576:575–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellard S, Lango Allen H, De Franco E, et al. Improved genetic testing for monogenic diabetes using targeted next-generation sequencing. Diabetologia 2013;56:1958–1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wakeling MN. SavvySuite [Internet], 2018. Available from https://github.com/rdemolgen/SavvySuite. Accessed 5 December 2018

- 11.Wakeling MN, De Franco E, Hattersley AT, Ellard S. Making the most of targeted sequencing: detecting CNVs and homozygous regions using off-target reads with SavvyCNV. Selected abstract oral presentation at the 67th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics, 17–21 October 2017, at the Orange County Convention Center, Orlando, FL [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson MB, Patel KA, De Franco E, et al. A type 1 diabetes genetic risk score can discriminate monogenic autoimmunity with diabetes from early-onset clustering of polygenic autoimmunity with diabetes. Diabetologia 2018;61:862–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burton PR, Clayton DG, Cardon LR, et al.; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium . Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature 2007;447:661–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barker JM, Triolo TM, Aly TA, et al. Two single nucleotide polymorphisms identify the highest-risk diabetes HLA genotype: potential for rapid screening. Diabetes 2008;57:3152–3155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oram RA, Patel K, Hill A, et al. A type 1 diabetes genetic risk score can aid discrimination between type 1 and type 2 diabetes in young adults. Diabetes Care 2016;39:337–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald TJ, Colclough K, Brown R, et al. Islet autoantibodies can discriminate maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) from type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2011;28:1028–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taplin CE, Barker JM. Autoantibodies in type 1 diabetes. Autoimmunity 2008;41:11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hämäläinen AM, Ilonen J, Simell O, et al. Prevalence and fate of type 1 diabetes-associated autoantibodies in cord blood samples from newborn infants of non-diabetic mothers. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2002;18:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanley HM, Norris JM, Barriga K, et al.; Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY) . Is presence of islet autoantibodies at birth associated with development of persistent islet autoimmunity? The Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY). Diabetes Care 2004;27:497–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusters MAA, Verstegen RHJ, Gemen EFA, de Vries E. Intrinsic defect of the immune system in children with Down syndrome: a review. Clin Exp Immunol 2009;156:189–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillespie KM, Gale EAM, Bingley PJ. High familial risk and genetic susceptibility in early onset childhood diabetes. Diabetes 2002;51:210–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomson G, Valdes AM, Noble JA, et al. Relative predispositional effects of HLA class II DRB1-DQB1 haplotypes and genotypes on type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Tissue Antigens 2007;70:110–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erlich HA, Zeidler A, Chang J, et al. HLA class II alleles and susceptibility and resistance to insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in Mexican-American families. Nat Genet 1993;3:358–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winkler C, Krumsiek J, Buettner F, et al. Feature ranking of type 1 diabetes susceptibility genes improves prediction of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2014;57:2521–2529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamzeh AR, Nair P, Al Ali MT The profile of HLA-DRB1 alleles in Arabs with type 1 diabetes; meta-analyses. HLA 2016;87:25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Passos GA, Speck-Hernandez CA, Assis AF, Mendes-da-Cruz DA Update on Aire and thymic negative selection. Immunology 2018;153:10–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aaltonen J, Björses P, Perheentupa J, et al.; Finnish-German APECED Consortium . An autoimmune disease, APECED, caused by mutations in a novel gene featuring two PHD-type zinc-finger domains. Nat Genet 1997;17:399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skogberg G, Lundberg V, Lindgren S, et al. Altered expression of autoimmune regulator in infant down syndrome thymus, a possible contributor to an autoimmune phenotype. J Immunol 2014;193:2187–2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray D, Abramson J, Benoist C, Mathis D Proliferative arrest and rapid turnover of thymic epithelial cells expressing Aire. J Exp Med 2007;204:2521–2528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto M, Nishikawa Y, Nishijima H, Morimoto J, Matsumoto M, Mouri Y Which model better fits the role of aire in the establishment of self-tolerance: the transcription model or the maturation model? Front Immunol 2013;4:210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson MS, Su MA AIRE expands: new roles in immune tolerance and beyond. Nat Rev Immunol 2016;16:247–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lima FA, Moreira-Filho CA, Ramos PL, et al. Decreased AIRE expression and global thymic hypofunction in Down syndrome. J Immunol 2011;187:3422–3430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giménez-Barcons M, Casteràs A, Armengol M del P, et al. Autoimmune predisposition in Down syndrome may result from a partial central tolerance failure due to insufficient intrathymic expression of AIRE and peripheral antigens. J Immunol 2014;193:3872–3879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrett JC, Clayton DG, Concannon P, et al.; Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium . Genome-wide association study and meta-analysis find that over 40 loci affect risk of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet 2009;41:703–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ge Y, Paisie TK, Newman JRB, McIntyre LM, Concannon P UBASH3A mediates risk for type 1 diabetes through inhibition of T-cell receptor–induced NF-κB signaling. Diabetes 2017;66:2033–2043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun S-C NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2017;2:17023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arenas-Ramirez N, Woytschak J, Boyman O Interleukin-2: biology, design and application. Trends Immunol 2015;36:763–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sullivan KD, Lewis HC, Hill AA, et al. Trisomy 21 consistently activates the interferon response. eLife 2016;5:e16220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Theofilopoulos AN, Baccala R, Beutler B, Kono DH Type I interferons (alpha/beta) in immunity and autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol 2005;23:307–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lombardi A, Tsomos E, Hammerstad SS, Tomer Y Interferon alpha: the key trigger of type 1 diabetes. J Autoimmun 2018;94:7–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferreira RC, Guo H, Coulson RMR, et al. A type I interferon transcriptional signature precedes autoimmunity in children genetically at risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2014;63:2538–2550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Picard C, Belot A Does type-I interferon drive systemic autoimmunity? Autoimmun Rev 2017;16:897–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.