Abstract

Human motion capture is used in various fields to analyse, understand and reproduce the diversity of movements that are required during daily-life activities. The proposed dataset of human gait has been established on 50 adults healthy and injury-free for lower and upper extremities in the most recent six months, with no lower and upper extremity surgery in the last two years. Participants were asked to walk on a straight level walkway at 5 speeds during one unique session: 0–0.4 m.s−1, 0.4–0.8 m.s−1, 0.8–1.2 m.s−1, self-selected spontaneous and fast speeds. Three dimensional trajectories of 52 reflective markers spread over the whole body, 3D ground reaction forces and moment, and electromyographic signals were simultaneously recorded. For each participants, a minimum of 3 trials per condition have been made available in the dataset for a total of 1143 trials. This dataset could increase the sample size of similar datasets, lead to analyse the effect of walking speed on gait or conduct unusual analysis of gait thanks to the full body markerset used.

Subject terms: Biomedical engineering, Motor cortex

| Design Type(s) | modeling and simulation objective • data integration objective |

| Measurement Type(s) | gait • force • muscle electrophysiology trait |

| Technology Type(s) | digital camera • force transducer • electromyography |

| Factor Type(s) | speed • sex • age • height • weight • body mass index (BMI) • limb length |

| Sample Characteristic(s) | Homo sapiens • whole body |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data (ISA-Tab format)

Background & Summary

Human motion capture is nowadays commonly used in various fields to analyse, understand and reproduce the diversity of movements that can be produced during daily-life activities. In clinical practice, the emergence of evidence-based medicine promoted the development of quantitative assessment tools for the diagnosis and treatment of pathology-related movement disorders. In particular, the process of gait disorders analysis currently often consists of the measurement of joint kinematics and kinetics in three dimensions1. This assessment is called clinical gait analysis (CGA) and attempts to provide an objective record that quantifies the magnitude of deviations from normal gait2. On this basis, a set of pathology-related impairments having the most impact on gait is identified and can be used to target the treatment3.

However, the identification of deviations is highly dependent with the characteristics of the normative database used4. Special attention is then required to discriminate the differences between pathological and asymptomatic populations that could confound deviations. In particular, the gait of pathological populations is often observed at their own self-selected walking speed and compared to normative data established at the spontaneous walking speed of an asymptomatic population5. Since the spontaneous walking speed of pathological populations (e.g. ranged between 0.18 and 1.03 m.s−1 for stroke6) is often slower than for an asymptomatic population (ranged between 1.04 and 1.60 m.s−1 7), a walking speed mismatch appears. Because walking speed is known to affect kinematics, kinetics, spatiotemporal parameters and muscular activity8, the identification of gait deviations can then become challenging since both pathology and walking speed difference may contribute to them9. But walking speed is not the only variable that could be source of a mismatch in comparison of a patient and an asymptomatic population. Demographic and anthropometric parameters may also affect CGA interpretation. Recently, Chehab et al.10 demonstrated the impact of walking speed, but also age, sex and body mass index (BMI) on 3D kinematics and kinetics of the lower limb during gait. While walking speed was the most influential variable, the authors highlighted the influence of demographic and anthropometric parameters on very common parameters (e.g. pelvis tilt, peak of hip extension) used in the identification of gait deviations.

Several datasets have been made available in the literature and can be used to ease the establishment of a broad normative database allowing to match patient characteristics11–14. However, few datasets include all the common parameters on a large number of subjects (i.e. spatio-temporal, kinematics, kinetics, electromyography signals). The proposed dataset has been established on 50 healthy participants aged between 19 and 67 years. They were asked to walk on a straight level walkway at five different walking speeds: between 0 and 0.4 m.s−1, between 0.4 and 0.8 m.s−1, between 0.8 and 1.2 m.s−1, self-selected spontaneous speed and self-selected fast speed. Three dimensional trajectories of 52 cutaneous reflective markers spread over the whole body, 3D ground reaction forces and moment, and electromyographic signals were simultaneously recorded. For each participant, 3 trials for each walking speed condition plus one static were recorded and pre-processed, for a total of 1143 trials. This dataset could increase population sample size of similar datasets, lead to analyse the effect of walking speed on gait or conduct unusual analysis of gait characteristics thanks to the full body markerset used.

Methods

Participants

Fifty participants (24 women and 26 men, 37.0 ± 13.6 years, 1.74 ± 0.09 m, 71.0 ± 12.3 kg) were recruited on a voluntary basis. The study was approved by the institutional medical ethic committee of the Rehazenter and follows the recommendations of the declaration of Helsinki. The participants gave their informed consent to participate in the study. All participants were asymptomatic, i.e. healthy and injury free for both lower and upper extremities in the most recent six months, and no lower or upper extremity surgery in the last two years. Furthermore, only participants having a leg length difference lower than 1.5% of the height (corresponding to a maximum of 0.03 m) were included in this study to avoid an effect of a leg length discrepancy in the dataset.

Procedure

For each participant, the entire data collection was acquired in a single session which lasted approximately 2 hours. All the sessions were managed by the same experienced operator. The following procedure was adopted:

Calibration of the systems: This calibration was performed following the instructions available in the manufacturer’s documentation, including the definition of the inertial coordinate system, the dynamic calibration of the cameras, and the zeroing of forceplates.

Introduction to the participant: The operator introduced the laboratory, outlined the need to establish the database, and briefly explained the conduct of the session, including the material used. The participant could ask questions at any time.

Interview: An interview allowed collecting information at this stage about participant’s health condition and sports habits (Supplementary Table 1).

Preparation of the participant: The participant was asked to change clothes to tight-fitting clothes or underwear, including removing shoes and socks as the acquisition was barefoot, and tied up their hair if necessary. The operator also collected participants’ anthropometric and demographic information (Online-only Table 1). The participant was then equipped with EMG electrodes and cutaneous reflective markers (see section Records).

Static record: The participant was standing upright with lower and upper limbs outstretched, palms facing forward, right head with straight eyes. Five seconds without any movement were recorded. The record was verified by the operator. A new standing trial was performed if any marker was missing or movements perturbed the record.

Walking trials: The participant was asked to walk back and forth on a 10-m straight level walkway. The instruction given was “to walk as naturally as possible, looking forward”. No directive was given about the forceplates to avoid a conscious adaptation of the walk. A minimum of 3 trials were recorded for each condition. All trials were rapidly verified by the operator. Five conditions of walking speed were recorded: between 0 and 0.4 m.s−1 (C1), between 0.4 and 0.8 m.s−1 (C2), between 0.8 and 1.2 m.s−1 (C3), self-selected spontaneous speed (C4) and self-selected fast speed (C5). Conditions C1, C2 and C3 were induced by a metronome15 and correspond to the three groups described by Perry16 (i.e. household ambulators, limited community ambulators and community ambulators). An adaptation time to the imposed cadence was foreseen for these 3 conditions and the velocity of the first trial was checked to be in the expected range of speed. C4 and C5 were self-selected conditions in response to the instructions to walk respectively “as usual” and “fast but not running”.

Session ending: All markers and electrodes were removed. Additional explanations about the records were given to the participants while showing some videos and 3D animations.

Online-only Table 1.

Anthropometric and demographic information of the participants.

| Subject ID | Gender | Age (year) | Height (m) | Mass (Kg) | BMI (kg.m−2) | Right leg length (m) | Left leg length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014001 | M | 31 | 1.66 | 67.0 | 24.5 | 0.731 | 0.735 |

| 2014002 | W | 48 | 1.64 | 65.4 | 24.3 | 0.774 | 0.770 |

| 2014003 | W | 28 | 1.56 | 50.0 | 20.5 | 0.721 | 0.720 |

| 2014004 | M | 23 | 1.77 | 72.5 | 23.4 | 0.829 | 0.848 |

| 2014005 | M | 25 | 1.83 | 73.5 | 21.9 | 0.864 | 0.892 |

| 2014006 | M | 23 | 1.76 | 73.0 | 23.6 | 0.849 | 0.856 |

| 2014007 | W | 44 | 1.69 | 65.0 | 22.8 | 0.837 | 0.838 |

| 2014008 | W | 30 | 1.66 | 57.1 | 20.7 | 0.802 | 0.793 |

| 2014009 | M | 57 | 1.88 | 86.0 | 24.3 | 0.897 | 0.890 |

| 2014011 | M | 59 | 1.80 | 63.4 | 19.6 | 0.849 | 0.854 |

| 2014013 | W | 26 | 1.70 | 61.3 | 21.2 | 0.789 | 0.784 |

| 2014014 | M | 29 | 1.80 | 92.0 | 28.4 | 0.842 | 0.847 |

| 2014015 | W | 22 | 1.58 | 67.0 | 26.8 | 0.716 | 0.708 |

| 2014019 | W | 26 | 1.76 | 73.8 | 24.0 | 0.819 | 0.828 |

| 2014022 | W | 48 | 1.71 | 59.8 | 20.5 | 0.819 | 0.826 |

| 2014024 | M | 33 | 1.92 | 87.5 | 23.7 | 0.906 | 0.906 |

| 2014025 | W | 31 | 1.66 | 80.5 | 29.2 | 0.781 | 0.788 |

| 2014029 | M | 38 | 1.89 | 89.9 | 25.3 | 0.877 | 0.885 |

| 2014030 | W | 62 | 1.70 | 60.7 | 21.0 | 0.802 | 0.806 |

| 2014031 | M | 21 | 1.77 | 67.2 | 21.4 | 0.802 | 0.822 |

| 2014033 | W | 24 | 1.60 | 63.5 | 24.8 | 0.706 | 0.714 |

| 2014034 | M | 21 | 1.84 | 89.6 | 26.5 | 0.902 | 0.899 |

| 2014040 | W | 19 | 1.55 | 56.5 | 23.5 | 0.734 | 0.715 |

| 2014046 | W | 40 | 1.65 | 61.8 | 22.7 | 0.850 | 0.853 |

| 2014048 | W | 40 | 1.64 | 61.5 | 22.9 | 0.810 | 0.816 |

| 2014049 | M | 32 | 1.74 | 72.2 | 23.8 | 0.841 | 0.835 |

| 2014050 | W | 28 | 1.64 | 61.9 | 23.0 | 0.750 | 0.758 |

| 2014051 | M | 25 | 1.91 | 88.0 | 24.1 | 0.920 | 0.915 |

| 2014052 | M | 25 | 1.82 | 79.5 | 24.0 | 0.871 | 0.858 |

| 2014053 | W | 21 | 1.72 | 62.8 | 21.2 | 0.835 | 0.822 |

| 2015002 | M | 39 | 1.74 | 74.0 | 24.4 | 0.828 | 0.838 |

| 2015003 | M | 52 | 1.77 | 87.2 | 27.8 | 0.843 | 0.847 |

| 2015004 | W | 35 | 1.70 | 62.0 | 21.5 | 0.802 | 0.809 |

| 2015005 | M | 48 | 1.90 | 89.4 | 24.8 | 0.874 | 0.877 |

| 2015007 | W | 63 | 1.66 | 60.2 | 21.8 | 0.755 | 0.752 |

| 2015013 | W | 58 | 1.69 | 73.0 | 25.6 | 0.808 | 0.808 |

| 2015015 | W | 50 | 1.73 | 68.0 | 22.7 | 0.816 | 0.829 |

| 2015016 | W | 46 | 1.69 | 76.0 | 26.6 | 0.855 | 0.829 |

| 2015017 | W | 41 | 1.67 | 60.5 | 21.7 | 0.805 | 0.806 |

| 2015020 | M | 43 | 1.79 | 95.0 | 29.6 | 0.845 | 0.846 |

| 2015021 | W | 30 | 1.69 | 58.0 | 20.3 | 0.775 | 0.788 |

| 2015026 | W | 64 | 1.71 | 51.5 | 17.7 | 0.800 | 0.814 |

| 2015027 | M | 51 | 1.72 | 65.5 | 22.1 | 0.791 | 0.788 |

| 2015030 | M | 24 | 1.87 | 86.0 | 24.6 | 0.917 | 0.917 |

| 2015032 | M | 26 | 1.72 | 50.8 | 17.2 | 0.803 | 0.817 |

| 2015035 | M | 38 | 1.77 | 81.5 | 26.0 | 0.819 | 0.839 |

| 2015037 | M | 42 | 1.76 | 66.1 | 21.3 | 0.837 | 0.850 |

| 2015041 | M | 31 | 1.88 | 74.8 | 21.2 | 0.876 | 0.857 |

| 2015042 | M | 67 | 1.83 | 98.0 | 29.3 | 0.855 | 0.874 |

| 2015043 | M | 21 | 1.78 | 74.0 | 23.4 | 0.840 | 0.833 |

Records

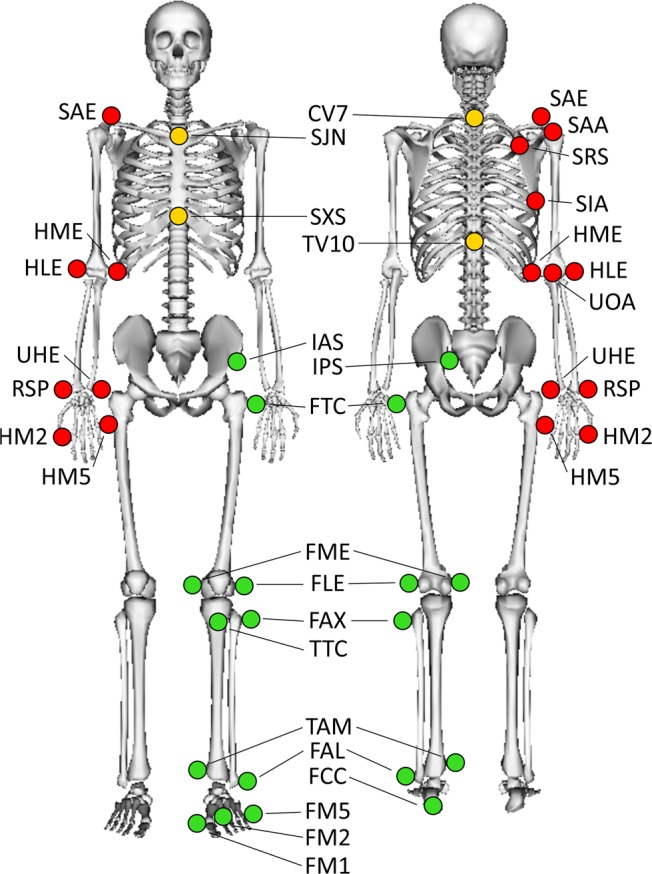

A 10-camera optoelectronic system sampled at 100 Hz (OQUS4, Qualisys, Sweden) was used to track the three-dimensional (3D) trajectories of a set of 52 cutaneous reflective markers. The markerset (Fig. 1, Table 1) was defined to allow the use of the biomechanical model proposed by Dumas and Wojtusch17. This model follows the recommendations of the International Society of Biomechanics (ISB)18,19 for the definitions of joint coordinate systems and joint centres. Marker placement was achieved by anatomical palpation (anatomical landmarks reported in Table 1) following the guideline provided by Van Sint Jan20 and remained unchanged during all trials. The same experienced physiotherapist performed both anatomical palpation and marker placement on all included participants. Two forceplates sampled at 1500 Hz (OR6-5, AMTI, USA) were used to record 3D ground reaction force and moment. These forceplates were embedded in the middle of the walkway travelled during the overground walking trials. A wireless electromyographic (EMG) system sampled at 1500 Hz (Desktop DTS, Noraxon, USA) was used to record the EMG signals collected by 8 probes connected to pairs of surface electrodes with a diameter of 10 mm (Ambu Neuroline 720, Ambu, Denmark). Skin preparation, inter-electrode distance, and electrode locations followed the recommendations of the Surface Electromyography for the Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles (SENIAM) project21. Skin preparation consisted in cleaning with alcohol, preceded by shaving, when necessary. An inter-electrode distance of 20 mm was applied for each muscle. EMG signals were recorded on 8 muscles of the right leg: gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, rectus femoris, vastus medialis, semitendinosus, gastrocnemius medialis, soleus, and tibialis anterior. In order to reduce the baseline noise contamination due to movement artefacts, each probe with related cables and electrodes were maintained using a self-adherent wrap (Coban, 3 M, USA). All these systems were synchronised using the Qualisys Track Manager software (QTM 2.8.1065, Qualisys, Sweden).

Fig. 1.

Reflective cutaneous markers placed by anatomical palpation on the participants. Only left side markers have been illustrated for the lower limbs (green markers) and right side markers for the upper limbs (red markers). The anatomical description and full name of each marker are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Marker trajectories stored in c3d files.

| Labels | Format | Dim. | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L_IAS | Real | n* × 3 | mm | Left anterior-superior iliac spine coordinates |

| L_IPS | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left posterior-superior iliac spine coordinates |

| R_IPS | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right posterior-superior iliac spine coordinates |

| R_IAS | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right anterior-superior iliac spine coordinates |

| L_FTC | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left greater trochanter coordinates |

| L_FLE | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left lateral femoral epicondyle coordinates |

| L_FME | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left medial femoral epicondyle coordinates |

| L_FAX | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left fibula head coordinates |

| L_TTC | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left tibial tuberosity coordinates |

| L_FAL | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left lateral tibial malleolus coordinates |

| L_TAM | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left medial tibial malleolus coordinates |

| L_FCC | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left posterior calcaneus coordinates |

| L_FM1 | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left 1st metatarsal head coordinates |

| L_FM2 | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left 2nd metatarsal head coordinates |

| L_FM5 | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left 5th metatarsal head coordinates |

| R_FTC | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right greater trochanter coordinates |

| R_FLE | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right lateral femoral epicondyle coordinates |

| R_FME | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right medial femoral epicondyle coordinates |

| R_FAX | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right fibula head coordinates |

| R_TTC | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right tibial tuberosity coordinates |

| R_FAL | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right lateral tibial malleolus coordinates |

| R_TAM | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right medial tibial malleolus coordinates |

| R_FCC | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right posterior calcaneus coordinates |

| R_FM1 | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right 1st metatarsal head coordinates |

| R_FM2 | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right 2nd metatarsal head coordinates |

| R_FM5 | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right 5th metatarsal head coordinates |

| CV7 | Real | n × 3 | mm | 7th cervical vertebra coordinates |

| TV10 | Real | n × 3 | mm | Spinous process of the 10th thoracic vertebrae coord. |

| SXS | Real | n × 3 | mm | Suprasternal notch coordinates |

| SJN | Real | n × 3 | mm | Xiphoid process coordinates |

| L_SIA | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left acromial tip coordinates |

| L_SRS | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left spine root coordinates |

| L_SAA | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left acromial angle coordinates |

| L_SAE | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left acromial edge coordinates |

| L_HLE | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left lateral humerus epicondyle coordinates |

| L_HME | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left medial humerus epicondyle coordinates |

| L_UOA | Real | n × 3 | mm | Apex of the left olecranon coordinates |

| L_RSP | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left radius styloid process coordinates |

| L_UHE | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left ulnar styloid process coordinates |

| L_HM2 | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left head of the 2nd metacarpus coordinates |

| L_HM5 | Real | n × 3 | mm | Left head of the 5th metacarpus coordinates |

| R_SIA | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right acromial tip coordinates |

| R_SRS | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right spine root coordinates |

| R_SAA | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right acromial angle coordinates |

| R_SAE | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right acromial edge coordinates |

| R_HLE | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right lateral humerus epicondyle coordinates |

| R_HME | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right medial humerus epicondyle coordinates |

| R_UOA | Real | n × 3 | mm | Apex of the right olecranon coordinates |

| R_RSP | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right radius styloid process coordinates |

| R_UHE | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right ulnar styloid process coordinates |

| R_HM2 | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right head of the 2nd metacarpus coordinates |

| R_HM5 | Real | n × 3 | mm | Right head of the 5th metacarpus coordinates |

*Number of frames recorded at 100 Hz.

Data processing

Labelling of the marker trajectories was performed in the Qualisys Tracking Manager software (QTM 2.8.1065, Qualisys, Sweden) and all foot strike and foot off events were manually detected by the same experienced operator. Events were defined based on the threshold of 5 N applied on the vertical ground reaction force, or based on markers trajectories when ground reaction forces were not available. Raw marker trajectories, ground reaction forces and moments and EMG signals, as well as time events, were then exported in the standard c3d file format (https://www.c3d.org) and then imported and processed under Matlab (R2018a, The MathWorks, USA) using the Biomechanics ToolKit (BTK)22. Markers trajectories (expressed in mm) were interpolated when necessary using a reconstruction based on marker inter-correlations obtained from a principal component analysis23. Then, trajectories were smoothed using a 4th order Butterworth low pass filter with a 6 Hz cut-off frequency. Ground reaction forces and moments (expressed in N and N.mm, respectively) were smoothed using a 2th order Butterworth low pass filter with a 15 Hz cut-off frequency. Below the threshold of 5 N defined on the vertical ground reaction force, all of these forces and moments were set to zero. EMG signals (expressed in V) were band pass filtered between 30 and 300 Hz (4th order Butterworth filter) to reduce artefacts due to motion and electromagnetic fields. All processed data were cropped few frames before the first event and few frames after the last event, depending on the available data. Finally, they were stored in a new c3d file using BTK. These final c3d files are the ones reported in the present dataset.

Data Records

All data records are available from figshare24. They are all stored in c3d file format (https://www.c3d.org). This file format is a public binary file format supported by all motion capture system manufacturers and biomechanics software programs. It is commonly used to store, for a single trial, synchronized 3D markers coordinates and analog data as well as a set of metadata (e.g. measurement units, custom parameters specific to the manufacturer software application).

Trial files are referenced in our dataset as YYYYNNN_CV_TT.c3d and static files as YYYYNNN_ST.c3d, organised by folder YYYYNNN, with:

YYYY: year of the acquisition, e.g. 2014

NNN: identification of the subject (passage number by year), e.g. 001

CV: walking speed condition, i.e. C1, C2, C3, C4 or C5

TT: trial number, i.e. 01 to 05

For each of the 50 participants, at least 3 trials (one right and one left gait cycle per trial) for each of the 5 conditions plus one static have been made available in the dataset, for a total of 1143 trials. Structure, labels, format, dimension, unit and description of each variable stored in the c3d files are given in Tables 1–4. Trial by trial information about the availability of forceplate data is given in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 2.

Analog data stored in c3d files.

| Labels | Format | Dim. | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R_tibialis_anterior | Real | m* × 1 | V | EMG+ signal of the right Tibialis Anterior |

| R_soleus | Real | m × 1 | V | EMG signal of the right Soleus |

| R_gastrocnemius_medialis | Real | m × 1 | V | EMG signal of the right Gastrocnemius Med. |

| R_vastus_medialis | Real | m × 1 | V | EMG signal of the right Vastus Medialis |

| R_rectus_femoris | Real | m × 1 | V | EMG signal of the right Rectus Femoris |

| R_semitendinosus | Real | m × 1 | V | EMG signal of the right Semitendinosus |

| R_gluteus_maximus | Real | m × 1 | V | EMG signal of the right Gluteus Maximus |

| R_gluteus_medius | Real | m × 1 | V | EMG signal of the right Gluteus Medius |

| Fx1 | Real | m × 1 | N | Force applied by the foot on forceplate 1/X¤ |

| Fy1 | Real | m × 1 | N | Force applied by the foot on forceplate 1/Y |

| Fz1 | Real | m × 1 | N | Force applied by the foot on forceplate 1/Z |

| Mx1 | Real | m × 1 | N.mm | Moment applied by the foot on forceplate 1/X |

| My1 | Real | m × 1 | N.mm | Moment applied by the foot on forceplate 1/Y |

| Mz1 | Real | m × 1 | N.mm | Moment applied by the foot on forceplate 1/Z |

| Fx2 | Real | m × 1 | N | Force applied by the foot on forceplate 2/X |

| Fy2 | Real | m × 1 | N | Force applied by the foot on forceplate 2/Y |

| Fz2 | Real | m × 1 | N | Force applied by the foot on forceplate 2/Z |

| Mx2 | Real | m × 1 | N.mm | Moment applied by the foot on forceplate 2/X |

| My2 | Real | m × 1 | N.mm | Moment applied by the foot on forceplate 2/Y |

| Mz2 | Real | m × 1 | N.mm | Moment applied by the foot on forceplate 2/Z |

*Number of frames recorded at 1500 Hz.

+EMG: Electromyographic.

¤All forces and moments are expressed here in the coordinate system of the related forceplate (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for the coordinate system of each forceplate).

Table 3.

Forceplate data stored in c3d files.

| Structure | Labels | Format | Dim. | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ForcePlate(1) | P | Real | m* × 3 | mm | Centre of pressure coordinates (forceplate 1)¤ |

| F | Real | m × 3 | N | 3D ground reaction force (forceplate 1) | |

| M | Real | m × 3 | N.mm | 3D ground reaction moment (forceplate 1) | |

| ForcePlate(2) | P | Real | m* × 3 | mm | Centre of pressure coordinates (forceplate 2) |

| F | Real | m × 3 | N | 3D ground reaction force (forceplate 2) | |

| M | Real | m × 3 | N.mm | 3D ground reaction moment (forceplate 2) |

*Number of frames recorded at 1500 Hz.

¤All centres of pressure, forces and moments are expressed here in the inertial coordinate system.

Table 4.

Metadata* stored in c3d files.

| Structure | Labels | Format | Dim. | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | age | Integer | 1 × 1 | years | Age |

| gender | Integer | 1 × 1 | none | 0: woman, 1: man | |

| weight | Real | 1 × 1 | kg | Body weight | |

| height | Real | 1 × 1 | mm | Participant size | |

| R_legLength | Real | 1 × 1 | mm | Right leg length+ | |

| L_legLength | Real | 1 × 1 | mm | Left leg length | |

| Event | Right_Foot_Strike1 | Real | 1 × 1 | s | First right foot strike timing |

| Right_Foot_Strike2 | Real | 1 × 1 | s | Second right foot strike timing | |

| Right_Foot_Off | Real | 1 × 1 or 1 × 2 | s | Right foot off timings | |

| Left_Foot_Strike1 | Real | 1 × 1 | s | First left foot strike timing | |

| Left_Foot_Strike2 | Real | 1 × 1 | s | Second left foot strike timing | |

| Left_Foot_Off | Real | 1 × 1 or 1 × 2 | s | Left foot off timings |

*Additional metadata are stored by default (i.e. Copyright, Force_Platform, Point, Analog, Trial, Event_Context).

+Leg length is measured between the anterior-superior iliac spine and the medial tibial malleolus.

Technical Validation

Calibration of the optoelectronic system

As detailed in the procedure (see Methods), the optoelectronic system was calibrated before each session following the instructions available in the manufacturer’s documentation. In all calibration files, residuals (i.e. average of the different residuals of the 2D marker rays that belongs to the same 3D point) were below 2 mm, and the standard deviation of the reconstructed wand (i.e. calibration tool) length remained below 1.5 mm.

3D trajectories of cutaneous reflective markers

In all static and trial files, the 3D trajectories of cutaneous reflective markers were fully reconstructed (i.e. 0% of gap in the trajectories), and residuals remained below 4 mm.

Centre of pressure location

The accuracy of the centre of pressure location was not specifically assessed during these data records. However, the accuracy of the centre of pressure location has previously been estimated using the Caltester procedure (Visual 3D v6, C-Motion, USA) to 3.11 ± 0.69 mm along X axis, 0.98 ± 0.54 mm along the Y axis and 1.55 ± 0.11 along the Z axis for forceplate 1, 3.56 ± 0.89 mm along X axis, 3.10 ± 0.79 mm along the Y axis and 1.70 ± 0.12 along the Z axis for forceplate 2.

Usage Notes

The data records stored in c3d file format (https://www.c3d.org) can easily be read using c3d parsers such as the Biomechanics ToolKit (BTK) (http://biomechanical-toolkit.github.io/)22 and the ezc3d package (https://github.com/pyomeca/ezc3d). The Motion kinematic and kinetic analyzer (Mokka) can also be a convenient tool for 3D visualisation (http://biomechanical-toolkit.github.io/mokka/index.html). Anthropometric and demographic parameters of each participant are stored in the metadata of the related c3d files. Based on the markerset used in this study, joint kinematics and dynamics can be computed using the 3D Kinematics and Inverse Dynamics toolbox proposed by Dumas and freely available on the MathWorks File Exchange (https://nl.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/58021-3d-kinematics-and-inverse-dynamics).

Supplementary Information

ISA-Tab metadata file

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank all volunteers for their kind participation, and Angélique Remacle for the time spent to acquire this dataset.

Online-only Table

Author Contributions

C.S. and F.M. designed the protocol used to establish the presented dataset. C.S. prepared the data and double checked all records. F.M. developed the theory and performed the data treatment. C.S. and F.M. discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Code Availability

The custom Matlab code used to process data (see previous section) is freely available on the following repository: https://github.com/fmoissenet/CGA_Rehazenter_Toolbox/tree/article_ScientificData2019. The Biomechanics ToolKit (BTK) is also freely available on the following repository: http://biomechanical-toolkit.github.io/.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

ISA-Tab metadata

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41597-019-0124-4.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41597-019-0124-4.

References

- 1.Baker R. Gait analysis methods in rehabilitation. J. Neuroengineering Rehabil. 2006;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armand, S., Moissenet, F., de Coulon, G. & Bonnefoy-Mazure, A. Identifying and understanding gait deviations: critical review and perspectives. Mov. Sport Sci. - Sci. Mot. 77–88 (2017).

- 3.Moissenet, F. & Armand, S. Qualitative and quantitative methods of assessing gait disorders. In Orthopedic management of children with cerebral palsy. Nova Science Publishers, New York, USA (2015).

- 4.Schreiber C, Armand S, Moissenet F. The interpretation of conventional gait indices is related to the normative data’s walking speed. Gait Posture. 2017;57:217–218. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.06.380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinzone O, Schwartz MH, Thomason P, Baker R. The comparison of normative reference data from different gait analysis services. Gait Posture. 2014;40:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2014.03.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olney J, P Griffin S. M. & D McBride, I. Temporal, Kinematic, and Kinetic Variables Related to Gait Speed in Subjects With Hemiplegia: A Regression Approach. Phys. Ther. 1994;74:872–85. doi: 10.1093/ptj/74.9.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salbach NM, et al. Reference values for standardized tests of walking speed and distance: A systematic review. Gait Posture. 2015;41:341–360. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz MH, Rozumalski A, Trost JP. The effect of walking speed on the gait of typically developing children. J. Biomech. 2008;41:1639–1650. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoquart G, Detrembleur C, Lejeune T. Effect of speed on kinematic, kinetic, electromyographic and energetic reference values during treadmill walking. Neurophysiol. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008;38:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chehab EF, Andriacchi TP, Favre J. Speed, age, sex, and body mass index provide a rigorous basis for comparing the kinematic and kinetic profiles of the lower extremity during walking. J. Biomech. 2017;58:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2017.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuchi CA, Fukuchi RK, Duarte M. A public dataset of overground and treadmill walking kinematics and kinetics in healthy individuals. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4640. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodgins, J. CMU graphics lab motion capture database (2015).

- 13.Kirtley, C. CGA normative gait database (2014).

- 14.Moore JK, Hnat SK, van den Bogert AJ. An elaborate data set on human gait and the effect of mechanical perturbations. PeerJ. 2015;3:e918. doi: 10.7717/peerj.918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber C, Remacle A, Chantraine F, Kolanowski E, Moissenet F. Influence of a rhythmic auditory stimulation on asymptomatic gait. Gait Posture. 2016;50:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.07.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perry J, Garrett M, Gronley JK, Mulroy SJ. Classification of Walking Handicap in the Stroke Population. Stroke. 1995;26:982–989. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.26.6.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dumas, R. & Wojtusch, J. Estimation of the Body Segment Inertial Parameters for the Rigid Body Biomechanical Models Used in Motion Analysis. In Handbook of Human Motion (eds Müller, B. et al.) 1–31 (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

- 18.Wu G, et al. ISB recommendation on definitions of joint coordinate system of various joints for the reporting of human joint motion—part I: ankle, hip, and spine. J. Biomech. 2002;35:543–548. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(01)00222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu G, et al. ISB recommendation on definitions of joint coordinate systems of various joints for the reporting of human joint motion–Part II: shoulder, elbow, wrist and hand. J. Biomech. 2005;38:981–992. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Sint Jan, S. Color Atlas of Skeletal Landmark Definitions. Churchill Livingstone1623 (2007).

- 21.Hermens HJ, Freriks B, Disselhorst-Klug C, Rau G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2000;10:361–374. doi: 10.1016/S1050-6411(00)00027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barre A, Armand SS. Biomechanical ToolKit: Open-source framework to visualize and process biomechanical data. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2014;114:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gløersen Ø, Federolf P. Predicting Missing Marker Trajectories in Human Motion Data Using Marker Intercorrelations. PloS One. 2016;11:e0152616. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moissenet F, Schreiber C. 2019. A multimodal dataset of human gait at different walking speeds established on injury-free adult participants. figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Moissenet F, Schreiber C. 2019. A multimodal dataset of human gait at different walking speeds established on injury-free adult participants. figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The custom Matlab code used to process data (see previous section) is freely available on the following repository: https://github.com/fmoissenet/CGA_Rehazenter_Toolbox/tree/article_ScientificData2019. The Biomechanics ToolKit (BTK) is also freely available on the following repository: http://biomechanical-toolkit.github.io/.