Abstract

Pruritus is a common pathogenesis in liver diseases, including chronic hepatitis B (CHB). The phases of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection are defined in the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines. However, it still remains unclear whether the phase independently affects pruritus. The aim of this study was to clarify the effect of HBV infection phase on pruritus in patients with HBV. Of the 1,631 patients that attended the joint research facilities and were interviewed regarding their pruritus between January and June 2016, 196 patients with HBV infection were selected for the present analysis. One-to-one propensity score-matching using 13 variables was performed between participants in the hepatitis B e antigen (HBe-Ag)-positive/negative immune-active phase group and the inactive CHB phase group. Data from 47 patients per group were included in the final analysis. The prevalence of pruritus in the inactive CHB phase was significantly lower than in the HBe-Ag-positive/negative immune-active phase (23 vs. 47%; P=0.031). Being in the inactive CHB phase was determined to be an independent risk factor for pruritus (odds ratio, 0.35; 95% confidence interval, 0.143-0.842; P=0.019). The progression to inactive CHB phase may contribute to the amelioration of pruritus in patients with HBV infection.

Keywords: hepatitis B, pruritus, itching, dermatology, propensity score

Introduction

Pruritus is one of the common symptoms of chronic liver disease (1) and it impairs patients' quality of life (2-4). Therefore, the assessment of pruritus is important in the clinical management of chronic liver disease. Hepatitis B is a liver disease caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. The World Health Organization estimates that ~257 million people have chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infections worldwide (5). The clinical course and outcome of HBV infections vary according to immune balance between the viral replication and host immune responses (6). Although interferon-α (IFN-α) or nucleoside analogues are available against chronic infection of HBV, a complete elimination or cure is still difficult with current treatment strategies (7), suggesting that CHB infection-associated comorbidities will remain issues in patients.

Pruritus is observed in the patients with HBV infection and previous studies reported on the prevalence of pruritus in these patients (8,9). Bonacini (8) reported that 8.0% of patients with HBV infection had pruritus. Another previous study showed the prevalence differed according to the phase of HBV infection: It is significantly lower in the inactive CHB phase than in the hepatitis B e antigen (HBe-Ag)-positive/negative immune-active phase (22 vs. 41%), indicating that immune response and disease phase are associated with pruritus (9). However, it remains unclear whether the phase of HBV infection independently affects the prevalence of pruritus.

A study of the patients with chronic hepatitis C showed that liver fibrosis is an independent factor associated with pruritus (10). Furthermore, a study of primary biliary cholangitis, serum alkaline phosphatase was identified as an independent predictor of pruritus (11). These studies suggest that the pathogenesis of pruritus is different among chronic liver diseases and may be multifactorial. Therefore, an appropriate procedure is required to test statistical independence of factors that are potentially associated with pruritus in clinic. The current study aimed to investigate the effects of HBV infection phase on the prevalence of pruritus in patients with HBV infection using propensity score-matching.

Materials and methods

Patients

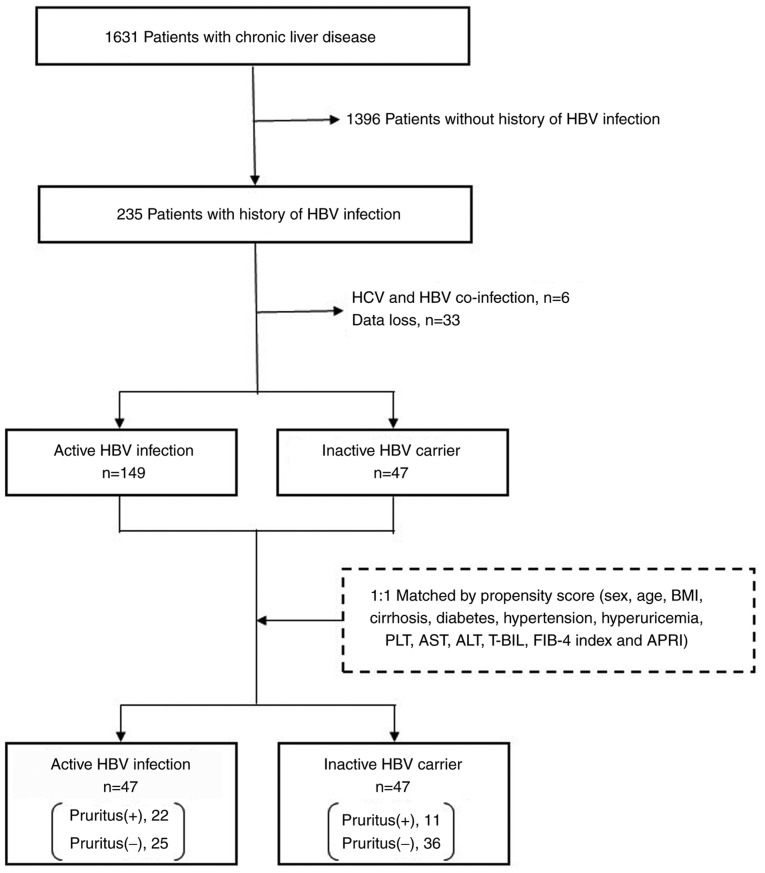

The current study performed a retrospective subgroup analysis of the cohort included in a previous multi-center, cross-sectional study (9). Continuous outpatients with various chronic liver diseases who attended the joint research facilities at Saga University Hospital, Yokohama City University Hospital, Kochi Medical School Hospital, JA Hiroshima General Hospital, Kurume University Hospital, Osaka City Juso Hospital, Kawasaki Hospital or Nara City Hospital between January and June 2016 were interviewed regarding pruritus. Patients with overt skin disease, including eczema and atopic dermatitis, were excluded from the survey and a total of 1,631 patients were included. Out of these patients, 235 were infected with HBV, of whom 39 patients were excluded due to missing data (n=33) or co-infection with hepatitis C virus (n=6). A total of 196 patients were enrolled in the current study and divided into two groups according to their HBV disease phase, as defined in the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines (6). Patients in HBe-Ag-positive/negative immune-active phase were classified as belonging to the active HBV infection (n=149) group, and those in inactive CHB phase were classified as belonging to the inactive HBV carrier (n=47) group. No patients were in the immune tolerant phase. To minimize differences in patient baseline characteristics between the groups, a one-to-one nearest-neighbor matching without replacement was performed based on propensity score techniques (12). No caliper was set, meaning that the propensity score distance allowed for matching in order to prevent a decrease in the number of cases. The propensity score was calculated using 13 variables: Sex, age, body mass index, cirrhosis, diabetes, hypertension, hyperuricemia, platelet count, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total bilirubin, FIB-4 index (13) and AST-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) (14). Well-balanced groups were obtained after matching; the data from 47 inactive HBV carriers and 47 matched patients with active HBV infection were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Patient selection. HBV, hepatitis B virus; BMI, body mass index; PLT, platelet count; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; T-BIL, total bilirubin; FIB-4, fibrosis 4; APRI, AST to platelet ratio index.

Liver cirrhosis, diabetes, hypertension and hyperuricemia were diagnosed by the physician in charge of the case on the basis of the patient's clinical background and history. Liver cirrhosis was definitively diagnosed on the basis of liver histologic assessment, liver stiffness measured by transient elastography (15), fibrosis-4 index, APRI and overt findings of cirrhosis, such as ascites, jaundice, hepatic encephalopathy and esophagogastric varices. Diabetes and hyperuricemia were diagnosed by blood tests.

Evaluation of pruritus

Data from the interviews were recorded by physicians using a standardized interview form, which contained questions regarding the existence of pruritus, the location of any itch, the duration of itching and its circadian variation and seasonality. The severity of pruritus was evaluated using the visual analogue scale (VAS) (16), which quantified the degree of pruritus from 0 (no pruritus) to 10 (maximum pruritus), according to the patients' subjective perception. Differences in the VAS scored between day and night were evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Two statistical experts (SK and AK) analyzed the data. Patient characteristics were compared according to the HBV infection phase and the presence of itching. The χ2 and Fisher's exact test were used to perform intergroup comparisons of categorical variables. The Mann-Whitney U or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used for intergroup comparisons of continuous variables. To identify independent predictors of pruritus, a univariate analysis was performed using a logistic regression model in patients after propensity score-matching using the ‘Matching’ package in R (version 3.3.2; https://www.r-project.org/index.html). All statistical analyses were performed using R. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Characteristics of the study group

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table I. Before propensity score-matching, the prevalence of pruritus was significantly lower in inactive HBV carriers than in patients with active HBV infection (23 vs. 41%; P=0.045). Prior to matching, liver cirrhosis was significantly less prevalent in inactive HBV carriers than in patients with active HBV infection (8.5 vs. 25%; P=0.022). The prevalence of pruritus in inactive HBV carriers was also significantly lower than in patients with active HBV infection, after propensity score-matching (23 vs. 47%; P=0.031).

Table I.

Patient characteristics according to HBV infection phase before and after propensity score-matching.

| Before matching | After matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active HBV infection (n=149) | Inactive HBV carrier (n=47) | P-value | Active HBV infection (n=47) | Inactive HBV carrier (n=47) | P-value | |

| Sexa, female | 66(44) | 16(34) | 0.283 | 16(34) | 16(34) | 1.000 |

| Age (years)b | 83 26-97 | 61 35-85 | 0.792 | 61 39-81 | 61 35-85 | 0.971 |

| BMIb | 22.4 (15.0-34.7) | 22.5 (18.6-31.4) | 0.624 | 23.2 (18.0-29.8) | 22.5 (18.6-31.4) | 0.694 |

| Pruritusa | 61(41) | 11(23) | 0.045 | 22(47) | 11(23) | 0.031 |

| Cirrhosisa | 37(25) | 4 (8.5) | 0.022 | 5(11) | 4 (8.5) | 1.000 |

| Diabetesa | 27(18) | 5(11) | 0.325 | 5(11) | 5(11) | 1.000 |

| Hypertensiona | 36(24) | 7(15) | 0.256 | 7(15) | 7(15) | 1.000 |

| Hyperuricemiaa | 7 (4.7) | 3 (6.4) | 0.705 | 3 (6.4) | 3 (6.4) | 1.000 |

| PLT (x104/µl)b | 18.7 (5.4-94.9) | 21.1 (12.5-34.0) | 0.063 | 20.3 (7.4-94.9) | 21.1 (12.5-34.0) | 0.480 |

| AST (U/l)b | 24 13-182 | 24 13-58 | 0.870 | 23 14-63 | 24 13-58 | 0.534 |

| ALT (U/l)b | 20 5-275 | 24 5-97 | 0.737 | 20 5-84 | 24 5-97 | 0.796 |

| T–BIL (mg/dl)b | 0.8 (0.4-9.0) | 0.8 (0.5-1.5) | 0.589 | 0.8 (0.4-1.7) | 0.8 (0.5-1.5) | 0.678 |

| FIB-4 indexb | 1.800 (0.331-12.573) | 1.508 (0.400-5.057) | 0.107 | 1.490 (0.530-5.227) | 1.508 (0.400-5.057) | 0.932 |

| APRIb | 0.363 (0.096-3.233) | 0.336 (0.146-0.969) | 0.100 | 0.323 (0.105-1.154) | 0.336 (0.146-0.969) | 0.906 |

aData are presented as n (%).

bData are presented as median (range). Matching was performed by one-to-one nearest-neighbor matching without replacement based on a propensity score techniques. HBV, hepatitis B virus; BMI, body mass index; PLT, platelet count; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; T-BIL, total bilirubin; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; APRI, AST to platelet ratio index.

Features of pruritus

A total of 33 patients with pruritus (active HBV infection, 22; inactive HBV carrier, 11) were identified in the propensity-matched cohort and their itch locations are summarized in Table II. Patients with pruritus selected all applicable locations out of 15 listed areas. For all patients, the most common location was the back (73%) and the least common locations included the head (9.1%), hands (9.1%), groin (9.1%), foot (9.1%) and fingers (3.0%); no patients reported toe pruritus. The most common itch location in both groups was the back, but the proportion with back pruritus was significantly higher in patients with active HBV infection than in inactive HBV carriers (86 vs. 46%; P=0.038). No significant differences were observed for any other locations.

Table II.

Location of the itch in propensity-matched patients with pruritus, according to HBV infection phase.

| All (n=33) | Active HBV infection (n=22) | Inactive HBV carrier (n=11) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head | 3(9) | 2 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | 1.000 |

| Face | 6(18) | 4(18) | 2(18) | 1.000 |

| Neck | 7(21) | 5(23) | 2(18) | 1.000 |

| Upper arm | 5(15) | 4(18) | 1 (9.1) | 0.864 |

| Lower arm | 5(15) | 1 (4.5) | 4(36) | 0.059 |

| Hands | 3 (9.1) | 1 (4.5) | 2(18) | 0.521 |

| Fingers | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) | 0.720 |

| Abdomen | 8(24) | 5(23) | 3(27) | 1.000 |

| Back | 24(73) | 19(86) | 5(46) | 0.038 |

| Lower back | 7(21) | 5(23) | 2(18) | 1.000 |

| Groin | 3 (9.1) | 2 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | 1.000 |

| Thigh | 7(21) | 5(23) | 2(18) | 1.000 |

| Calf | 11(33) | 8(36) | 3(27) | 0.896 |

| Foot | 3 (9.1) | 2 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | 1.000 |

| Toes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

Data are presented as n (%). HBV, hepatitis B virus.

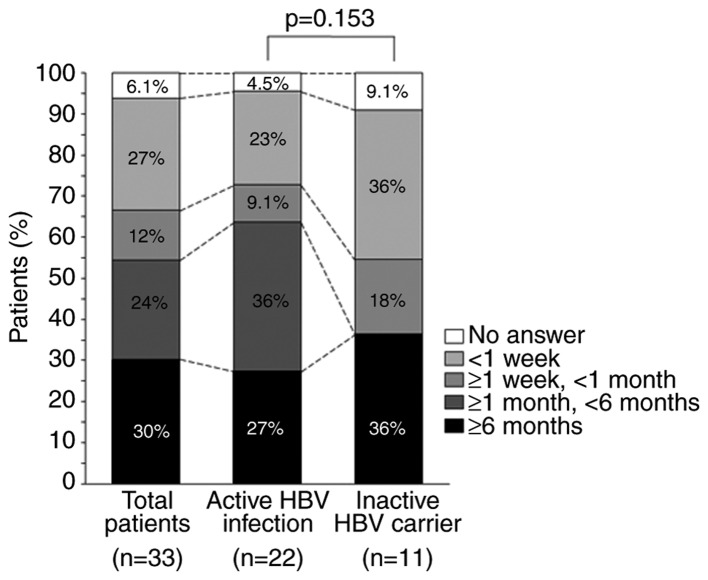

The duration for which pruritus lasted is shown in Fig. 2. Itching lasted ≥6 months in 30, 27 and 36% of all patients, patients with active HBV infection and in inactive HBV carriers, respectively. No patients in the inactive HBV carrier group reported itching of a duration ≥1 and <6 months, and there was no significant difference in the duration of pruritus between the two groups (P=0.153).

Figure 2.

Duration of pruritus in propensity-matched patients with pruritus. The duration of pruritus across all the patients (n=33), patients with active HBV infection (n=22) and in inactive HBV carriers (n=11) was recorded. HBV, hepatitis B virus.

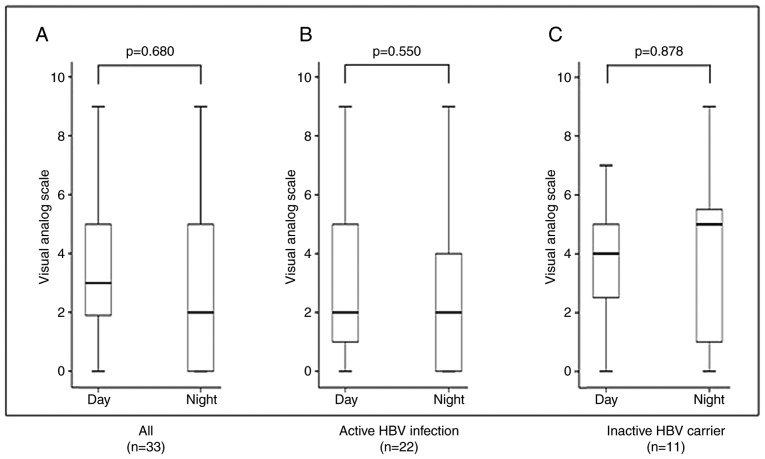

Fig. 3 shows the severity of itching according to VAS score and the difference in severity between day and night in the 33 patients with pruritus. There were no differences in VAS score between day and night across all the patients (P=0.680), in patients with active HBV infection (P=0.550) or in inactive HBV carriers (P=0.878). Seasonal exacerbation was identified at interview in 49% (16/33) of patients; 88% (14/16) reported exacerbation during the winter and 13% (2/16) reported exacerbation during the summer (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Severity of itching during the day and night in propensity-matched patients with pruritus. Visual analogue scale assessment of pruritus severity (A) across all patients, (B) in patients with active HBV infection and (C) in inactive HBV carriers. HBV, hepatitis B virus.

Independent factors associated with pruritus

In the propensity-matching cohort, patient characteristics according to the presence of pruritus are presented in Table III. The proportion of inactive HBV carriers in patients without pruritus was higher than that in patients with pruritus (59 vs. 33%; P=0.031). AST and APRI in patients without pruritus were significantly higher than in patients with pruritus (23 vs. 25 U/l; P=0.031; and 0.286 vs. 0.337; P=0.030). Being an inactive HBV carrier was identified as the only independent factor associated with pruritus (odds ratio, 0.35; 95% confidence interval, 0.143-0.842; P=0.019; Table IV).

Table III.

Patient characteristics of propensity-matched patients by presence or absence of pruritus.

| Pruritus (+)(n=33) | Pruritus (-)(n=61) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexa, female | 12(36) | 20(33) | 0.903 |

| Age (years)b | 59 35-81 | 61 35-81 | 0.252 |

| BMIb | 21.2 (18.0-31.43) | 23.1 (19.0-30.5) | 0.106 |

| Phase of HBV infectiona | 0.031 | ||

| Active HBV infection | 22(67) | 25(41) | |

| Inactive HBV carrier | 11(33) | 36(59) | |

| Cirrhosisa | 2 (6.1) | 7(12) | 0.628 |

| Diabetesa | 4(12) | 6(10) | 1.000 |

| Hypertensiona | 5(15) | 9(15) | 1.000 |

| Hyperuricemiaa | 2 (6.1) | 4 (6.6) | 1.000 |

| PLT (x104/µl)b | 20.9 (9.2-94.9) | 20.5 (7.4-34.0) | 0.440 |

| AST (U/l)b | 23 13-50 | 25 14-63 | 0.031 |

| ALT (U/l)b | 19 5-84 | 24 8-97 | 0.173 |

| T-BIL (mg/dl)b | 0.7 (0.4-1.4) | 0.8 (0.4-1.7) | 0.667 |

| FIB-4 indexb | 1.193 (0.516-5.227) | 1.569 (0.400-5.057) | 0.070 |

| APRIb | 0.286 (0.105-1.060) | 0.337 (0.172-1.154) | 0.030 |

aData are presented as n (%).

bData are presented as median (range). HBV, hepatitis B virus; BMI, body mass index; PLT, platelet count; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; T-BIL, total bilirubin; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; APRI, AST to platelet ratio index.

Table IV.

Factors associated with pruritus in propensity-matched patients with HBV infection.

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.727 | ||

| Male | 1 | Referent | |

| Female | 0.85 | 0.351-2.075 | |

| Age (years) | 0.98 | 0.944-1.011 | 0.177 |

| BMI | 0.91 | 0.793-1.040 | 0.164 |

| Phase of HBV infection | 0.019 | ||

| Active HBV infection | 1 | Referent | |

| Inactive HBV carrier | 0.35 | 0.143-0.842 | |

| Cirrhosis | 0.50 | 0.097-2.546 | 0.402 |

| Diabetes | 1.26 | 0.330-4.842 | 0.732 |

| Hypertension | 1.03 | 0.315-3.377 | 0.959 |

| Hyperuricemia | 1.09 | 0.188-6.277 | 0.925 |

| PLT (x104/µl) | 1.04 | 0.983-1.108 | 0.167 |

| AST (U/l) | 0.96 | 0.906-1.014 | 0.139 |

| ALT (U/l) | 0.99 | 0.967-1.019 | 0.572 |

| T–BIL (mg/dl) | 0.86 | 0.197-3.800 | 0.847 |

| FIB-4 index | 0.72 | 0.445-1.164 | 0.180 |

| APRI | 0.09 | 0.006-1.502 | 0.094 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HBV, hepatitis B virus; BMI, body mass index; PLT, platelet count; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; T-BIL, total bilirubin; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; APRI, AST to platelet ratio index.

Discussion

The prevalence of pruritus was significantly lower in inactive HBV carriers than in patients with active HBV infection. Furthermore, it was found that the phase of HBV infection was significantly associated with the presence of pruritus in the propensity score-matched cohort. Previous studies have characterized the predictors of pruritus in various liver diseases, including HBV infection (17,18); however, the effects of HBV infection per se and the phase of HBV infection on pruritus have not been assessed. A previous report suggested that active HBV infection is an independent positive risk factor for pruritus in patients with various chronic liver diseases (9). To the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies that established a predictor of pruritus in patients with HBV infections. The current study demonstrated that in patients with HBV, matched by propensity score, being an inactive HBV carrier was an independent negative risk factor for pruritus.

A previous study indicated the clinical features of pruritus in various chronic liver diseases. The following observations have been reported: i) The most frequent itch location is the back; ii) the duration of pruritus is ≥6 months in 38% of patients; and iii) the severity of pruritus is significantly higher during the day than during the night, and seasonal exacerbation occurs in the winter (9). In the present study, the back was identified as the most frequent itch location in both groups, while the frequency itself was significantly higher in patients with active HBV infection than in inactive HBV carriers. No HBV infection phase-associated differences in the duration of itching or the severity of pruritus were observed.

The mechanism of pruritus in HBV infection remains unclear. The association between HBV infection and skin lesions has been studied in a previous systematic review, in which ~2% of patients with HBV were found to have skin lesions and essential mixed cryoglobulinemic vasculitis was the most frequent type (19). It is well known that acute HBV infection causes Gianotti Crosti syndrome (GCS), which causes papular acrodermatitis, but skin lesions in GCS are not generally accompanied by itching (20,21). Therefore, the mechanism and pathogenesis of skin lesions in GCS may be different from those causing pruritus in the cases reported here. However, the presence of skin lesions in acute HBV infections suggested that HBV affected the skin independent of chronic liver damage or cirrhosis.

Immune complexes targeting hepatitis B surface antigen are considered to cause immune reactions that result in the skin lesions in GCS (22). Additionally, a study described cutaneous changes with itching following IFN administration to treat HBV infection or hepatitis B vaccination (23). Lupus, lupus-like lesions and bullous pemphigoid are generally accompanied by itching and have been observed during or after IFN treatment (23-25); while lichen planus, lichen-planus-like lesions and granuloma annulare have been described following hepatitis B immunization (26,27). These pieces of evidence suggest that extraordinary immune signaling is involved in the development of the skin lesions and itching present in HBV infection, and the immune response to HBV is likely to be key to pruritus. Liver dysfunction in HBV infection is caused by the host immune response, because HBV is a non-cytotoxic virus that does not cause liver damage (28,29). Therefore, the adverse effects of HBV infection depend on the extent of the immune response, which might also influence the development of skin lesions and pruritus. Indeed, the results of the current study suggested that HBV infection phase significantly affected the prevalence of pruritus.

The current study had few limitations. It evaluated a limited number of patients after matching (n=94) and was not conducted longitudinally. The collected data did not include quantitative HBV-DNA, HBe-Ag or detailed information on medications. Therefore, the impact of antiviral treatment, such as with nucleic acid analogs or IFN, on HBV-DNA levels was not evaluated. Serum AST and/or ALT levels in some patients were normalized due to antiviral treatment may have been included in the active HBV infection group, and some with abnormal AST and/or ALT levels resulting from fatty liver may have been included in the inactive HBV carrier group. Certain medications for concomitant diseases, including bezafibrate in primary biliary cholangitis, are known to affect pruritus in HBV infection (30). Further studies are required to identify the link between these medications and pruritus in HBV infection in more detail.

In conclusion, the current study identified that the HBV infection phase was a predictor of pruritus in patients with HBV infection. The prevalence of pruritus was significantly lower in patients with inactive CHB phase than in those with HBe-Ag-positive/negative immune-active phase, implying that an inactive CHB phase suppressed pruritus. Thus, the progression to an inactive CHB phase may contribute to the amelioration of pruritus in patients with HBV infection.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Mark Cleasby (Edanz Group) for language editing this manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets of the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

YE conceived and designed the study. SO, HT, HI, KI, MY, MO, HH, TK, HF, MK, YS, ST, HK, TT, TS, AN and YE collected and interpreted clinical data. SO curated data. SK and AK statistically analyzed data. SO wrote the first draft of the manuscript and HT and YE contributed to the writing of the manuscript. HI, KI, MY, MO, HH, TK, HF, MK, YS, ST, HK, TT, TS and AN reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The original study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. The original study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Review Committee of each facility. Opt-out informed consent was obtained from all participants at time of hospitalization.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Yamada T, Alpers DH, Kalloo AN, Kaplowitz N, Owyang C, Powell DN. Text of gastroenterology, 5th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2009 doi: 10.1002/9781444303254. editor. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung AC, Patel H, Meza-Cardona J, Cino M, Sockalingam S, Hirschfield GM. Factors that influence health-related quality of life in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:1692–1699. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-4013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benito de Valle M, Rahman M, Lindkvist B, Björnsson E, Chapman R, Kalaitzakis E. Factors that reduce health-related quality of life in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:769–775.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gutteling JJ, de Man RA, Busschbach JJ, Darlington AS. Overview of research on health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Neth J Med. 2007;65:227–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report, 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Diehl AM, Brunt EM, Cusi K, Charlton M, Sanyal AJ. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American gastroenterological association. Hepatology. 2012;55:2005–2023. doi: 10.1002/hep.25762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoofnagle JH, Doo E, Liang TJ, Fleischer R, Lok AS. Management of hepatitis B: Summary of a clinical research workshop. Hepatology. 2007;45:1056–1075. doi: 10.1002/hep.21627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonacini M. Pruritus in patients with chronic human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C virus infections. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:621–625. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(00)80847-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oeda S, Takahashi H, Yoshida H, Ogawa Y, Imajo K, Yoneda M, Koshiyama Y, Ono M, Hyogo H, Kawaguchi T, et al. Prevalence of pruritus in patients with chronic liver disease: A multicenter study. Hepatol Res. 2018;48:E252–E262. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cacoub P, Poynard T, Ghillani P, Charlotte F, Olivi M, Piette JC, Opolon P. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C. MULTIVIRC Group. Multidepartment Virus C. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2204–2212. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199910)42:10<2204::AID-ANR24>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talwalkar JA, Souto E, Jorgensen RA, Lindor KD. Natural history of pruritus in primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:297–302. doi: 10.1016/S1542-3565(03)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jupiter DC. Propensity score matching: Retrospective randomization? J Foot Ankle Surg. 2017;56:417–420. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, S Sulkowski M, Torriani FJ, Dieterich DT, Thomas DL, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43:1317–1325. doi: 10.1002/hep.21178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–526. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandrin L, Fourquet B, Hasquenoph JM, Yon S, Fournier C, Mal F, Christidis C, Ziol M, Poulet B, Kazemi F, et al. Transient elastography: A new noninvasive method for assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29:1705–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aitken RC. Measurement of feelings using visual analogue scales. Proc R Soc Med. 1969;62:989–993. doi: 10.1177/003591576906201005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akuta N, Kumada H, Fujiyama S, Kawamura Y, Sezaki H, Hosaka T, Kobayashi M, Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, Suzuki Y, et al. Predictors of pruritus in patients with chronic liver disease and usefulness of nalfurafine hydrochloride. Hepatol Res. 2018;48:45–50. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sumi R, Fukuda K, Irishio K, Hattori M, Sawai Y, Kogita S, Igura S, Yamaguchi Y, Matsumoto Y, Nakahara M, et al. Current status of pruritus in chronic liver diseases and efficacy of nalfurafine hydrochloride. Kanzo. 2017;58:486–493. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grigorescu I, Dumitrascu DL. Spontaneous and antiviral-induced cutaneous lesions in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:15860–15866. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i42.15860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gianotti F. Papular acrodermatitis of childhood. An Australia antigen disease. Arch Dis Child. 1973;48:794–799. doi: 10.1136/adc.48.10.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishimaru Y, Ishimaru H, Toda G, Baba K, Mayumi M. An epidemic of infantile papular acrodermatitis (Gianotti's disease) in Japan associated with hepatitis-B surface antigen subtype ayw. Lancet. 1976;1:707–709. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(76)93087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kacprzak-Bergman I, Halasa J. Frequency of complement third component (C3) and properdin factor (BF) phenotypes in patients with various clinical manifestations of HBV infection. Eur J Immunogenet. 1996;23:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.1996.tb00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kartal ED, Alpat SN, Ozgunes I, Usluer G. Adverse effects of high-dose interferon-alpha-2a treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Adv Ther. 2007;24:963–971. doi: 10.1007/BF02877700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yilmaz S, Cimen KA. Pegylated interferon alpha-2B induced lupus in a patient with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: Case report. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:1241–1243. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García-Porrúa C, González-Gay MA, Fernández-Lamelo F, Paz-Carreira JM, Lavilla E, González-López MA. Simultaneous development of SLE-like syndrome and autoimmune thyroiditis following alpha-interferon treatment. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1998;16:107–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Criado PR, de Oliveira Ramos R, Vasconcellos C, Jardim Criado RF, Valente NY. Two case reports of cutaneous adverse reactions following hepatitis B vaccine: Lichen planus and granuloma annulare. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:603–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mérigou D, Léauté-Labrèze C, Louvet S, Bioulac-Sage P, Taïeb A. Lichen planus in children: Role of the campaign for hepatitis B vaccination. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1998;125:399–403. (In French) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guidotti LG, Chisari FV. Immunobiology and pathogenesis of viral hepatitis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:23–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guidotti LG, Matzke B, Schaller H, Chisari FV. High-level hepatitis B virus replication in transgenic mice. J Virol. 1995;69:6158–6169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6158-6169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reig A, Sesé P, Parés A. Effects of Bezafibrate on outcome and pruritus in primary biliary cholangitis with suboptimal ursodeoxycholic acid response. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:49–55. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets of the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.