Abstract

Improvements in glycemic control using continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems have been demonstrated in the outpatient setting. Among hospitalized patients the use of CGM is largely investigational, particularly in the non-ICU setting. Although there is no commercially available closed-loop system, it has recently been evaluated in the non–critical care setting. Both CGMs and closed-loop systems may lead to improved glycemic control, decreased length of stay, reduced risk of adverse events related to severe hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. Limitations of inpatient use of CGM and closed-loop systems include lack of FDA approvals, inexperience with this technology, and costs related to supplies. Significant investment may be necessary for hospital staff training and for development of infrastructure to support inpatient use. Additional limitations for CGM systems includes potential inaccuracy of interstitial glucose measurements due to medication interferences, sensor lag, or sensor drift. Limitations for closed-loop systems also includes need for routine monitoring to detect infusion site issues as well as monitoring to ensure adequate insulin supply in reservoir to avoid abrupt cessation of insulin infusion leading to severe hyperglycemia. Hospital staff must be familiar with trouble-shooting and conversion to alternative mode of insulin delivery in the event of insulin pump malfunction. Given these complexities, implementation of closed-loop systems may require involvement of an endocrinology team, limiting widespread adoption. This article reviews current state of CGM and closed-loop system use in the non-ICU setting, available literature, advantages and limitations, as well as suggestions for future CGM design, specifically for the inpatient setting.

Keywords: continuous glucose monitoring, CGM, diabetes mellitus, glucose telemetry, hospital, inpatient

Within the United States, 30.3 million people or 9.4% of the population live with diabetes mellitus (DM).1 The percentage of hospitalized patients with DM is even higher, as people with diabetes have multiple and severe medical conditions which may lead to frequent and prolonged hospitalizations.2,3 In 2017, nearly $123 billion of hospital-related health care expenditure was incurred by those with DM.4 An estimated 32% of patient-days are reported to be spent in hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dl) for non–intensive care unit (ICU) patients.5,6 Hyperglycemia has been associated with adverse outcomes such as increased mortality, prolonged length of stay and higher risk for infections.2,7-11 While hyperglycemia is related to deleterious effects, inpatient hypoglycemia has similarly been associated with higher hospital charges, prolonged length of stay and increased inpatient and postdischarge mortality.12-14 Furthermore, increased glucose variability, another marker of dysglycemia, has also been associated with prolonged length of stay and increased postdischarge mortality.15

Guidelines on the management of hospitalized patients with DM have been developed to reduce the risk of inpatient hypoglycemia as well as to improve overall glycemic control.11 The current recommended method for monitoring hospitalized patients with DM in the non-ICU setting is bedside point of care (POC) capillary blood glucose testing. A significant limitation for this method is the frequency by which POC capillary blood glucose testing is typically performed, at most 4-6 times daily, leading to prolonged intervals of time when glucose values are not monitored. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems represent an alternative mode to measure glucose values with the advantage of greater frequency of monitoring as it is measured every few minutes. This continuous data would thereby eliminate prolonged intervals of time when patients’ glucoses may otherwise go unmonitored and can be utilized to guide treatment decisions and optimize DM regimens.

Some of the available CGM systems have received FDA approval to replace the need for capillary blood glucose testing.16-18 While CGM use in the outpatient setting is rising and has demonstrated benefits on glycemic control,19,20 the utility of these devices in the hospital setting, particularly in the non-ICU setting, is less understood given the paucity of safety and efficacy evidence currently available. A recent consensus statement released by the Diabetes Technology Society suggested potential benefit of use of CGM systems in the inpatient setting to improve overall glycemic control and to decrease hypoglycemia.21

Several CGM systems have been evaluated in the hospital setting. These can be categorized based on the source of the glucose sample; intravascular CGM from arterial or venous blood or subcutaneous CGM from interstitial fluid. A noninvasive (transdermal) option is also available.22 CGMs integrated with insulin pumps (closed-loop or sensor-augmented insulin pump systems) have also been evaluated among hospitalized patients.

Studies evaluating inpatient use of CGM systems have largely been conducted in the ICU, with only a minority within the noncritical, non-ICU setting.23 The following manuscript reports current state of CGM and closed-loop systems in the non-ICU setting, describes advantages and limitations, and reviews findings from studies evaluating CGM use and closed-loop systems in the non-ICU setting. In the current review article, we excluded studies performed in the ICU setting and those that evaluated the use of CGM combined with sensor-augmented pumps in the non-ICU setting. In addition, suggestions for future directions regarding development of CGM system design, particularly for inpatient use, is provided.

Search Methods

An electronic PubMed search was conducted to review available literature through June 2018. Keywords utilized included “inpatient continuous glucose monitoring,” “inpatient CGM,” “hospital CGM,” “non-critical care CGM,” “inpatient insulin pumps,” and “inpatient closed-loop systems.” Publications that examined CGM use in the non-ICU setting were included and those in the ICU setting were excluded from this review article.

Current State of CGM and Closed-Loop Systems in the Non-ICU Setting

During the past 10 years, diabetes technology has rapidly evolved and new devices have been developed. CGM and closed loop systems represent promising technology that can potentially decrease hypoglycemia and achieve better glycemic control in the inpatient setting. CGM systems are FDA approved for use in ambulatory patients however they remain largely investigational for use in the hospital setting. Despite a significant number of studies that have been performed, most them focused on the accuracy of the CGM systems, and importantly were mostly performed in the ICU setting. Only a few studies evaluated the use of CGM devices in the non–critical care setting and none were randomized clinical trials.23 As CGM use in the ambulatory setting is increasing, it is recommended to allow continued use during hospitalizations if proper institutional protocols have been developed.21 Notably, there is limited data available regarding transitioning CGM systems from an outpatient to inpatient setting. Therefore, in the absence of necessary infrastructure, continuation of CGM use while inpatient is limited.

Furthermore, there is even less information about the use of closed-loop systems in the non-ICU setting, as these systems are not commercially available, even in the outpatient setting. Although a hybrid-closed system has received FDA approval for use in the ambulatory setting, its use in the inpatient setting has not been evaluated.24

Non-ICU CGM Studies

A small number of studies have evaluated the use of CGM systems in the non-ICU setting (Table 1). Notably all of them utilized subcutaneous CGM systems. Study designs generally consisted of “blinded” CGM devices and primarily focused on validating the accuracy of CGM measured interstitial glucose against capillary blood glucose values. The use of CGM System Gold (Medtronic, Northridge, CA) was evaluated in 23 adult patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and 3 patients with type 1 diabetes (T1DM) admitted to medical and surgical general wards.25 There was no difference in the mean daily glucose values between CGM and POC capillary blood glucose testing. CGM devices detected more hypoglycemic episodes compared to capillary blood glucose testing (9 vs 1). Similarly, a study evaluating use of blinded iPro2 CGM devices (Medtronic, Northridge, CA) in 84 patients with T2DM admitted to medical wards showed greater detection of hypoglycemic episodes with CGM use versus capillary blood glucose testing (62 vs 4), including a 15-fold increase in detection of nocturnal hypoglycemia.26 CGM devices demonstrated a remarkable accuracy with 99% of the data points being in the clinically accurate Clarke error grid zones A+B. Another study evaluating use of blinded iPro2 CGM systems (Medtronic, Northridge, CA) in 38 patients with T2DM revealed similar mean daily glucose values between CGM and capillary blood glucose testing (176.2 mg/dl ± 33.9 vs 176.6 mg/dl ± 33.7, P = ns).27 Consistent with previously reported studies, the CGM systems were more likely to detect hypoglycemic episodes (55 vs 12). More than 50% of these events were detected between dinner and breakfast, an interval of time when POC capillary blood glucose testing is not routinely performed in the inpatient setting. This finding suggests that without the use of CGM systems these episodes may have remained undetected.

Table 1.

CGM Devices Used in Non-ICU Setting.

| Ref | Service | Diabetes technology | # patients | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | Medicine/surgery | Medtronic iPro2, blinded CGM vs POC | T1DM = 3 T2DM = 23 |

No significant difference in mean daily capillary glucose concentration, blind CGM vs POC (172.8 ± 43.2 vs 172.8 ± 48.6 mg/dL, P = ns). CGM detected more hypoglycemic episodes compared to capillary blood glucose testing (9 vs 1). |

| 25 | Medical wards | Medtronic iPro2, blinded CGM vs POC | T2DM = 84 | CGM/POC in range increased from 67.7%/67.2% (on Day 1) to 77.5%/78.6% (on the last day). CGM detected 15 more hypoglycemic episodes than POC during nighttime. CGM detected 12.5-fold more episodes of hyperglycemia (>250 ml/dL) than BG at nighttime. |

| 26 | Medical wards | Medtronic iPro2, blinded CGM vs POC | T2DM = 38 | No difference in daily average glucose levels between CGM and POC (176.2 mg/dl ± 33.9 vs 176.6 mg/dl ± 33.7, P = ns). CGM detected more hypoglycemic episodes than POC (55 vs 12, P < .01). |

| 29 | Medical wards | RT Dexcom G4 CGM | T2DM = 5 | Pilot study that showed that glucose values can be transmitted wirelessly to a monitoring device at the nursing station. 3 preventive actions of impending hypoglycemia were initiated by nursing staff. |

| 33 | Medical wards | Dexcom G4 CGM and Omnipod IP vs Dexcom G4 CGM vs MDI | T2DM = 16 | Pilot study that evaluated insulin pump and CGM initiation in the inpatient setting. CGM detected 19 where POC 12 hypoglycemic episodes (P = ns). Initiation of insulin pumps was feasible although labor intensive. |

In summary, when compared to POC capillary blood glucose testing, CGM systems were found to detect more hypoglycemic episodes.28 As the primary goal was to evaluate the accuracy of the CGM systems, these studies only utilized blinded devices. Therefore, the potential use of real-time (unblinded) CGM systems to prevent hypoglycemia and improve overall glycemic control has not been fully explored. A single case study described the use of an unblinded CGM system in a patient with T1DM admitted to the non-ICU setting.29 Due to CGM system restrictions, the device was placed near the patient’s bedside. Any audible or visual alarms were difficult to detect by the health care providers or staff unless they were in the immediate vicinity of the CGM monitoring device (receiver). Therefore, nurses were required to frequently enter the patient’s room to check the CGM receiver resulting in increased nursing workload.

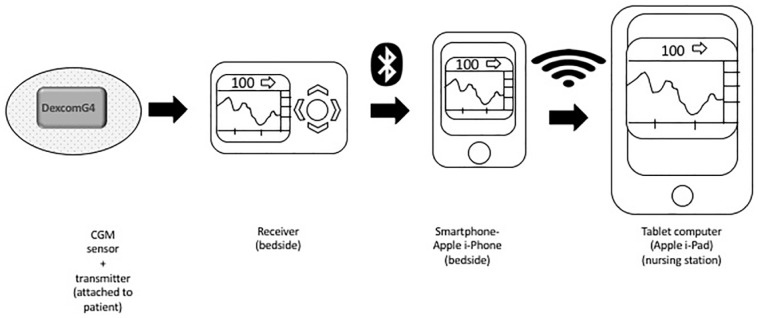

To overcome the above limitations, we explored ways to make the CGM glucose data more accessible to nursing staff and to the health care providers. We developed a system, that we termed the Glucose Telemetry System (GTS), which allowed the wireless transmission of CGM glucose values to a centrally placed monitoring device at the nursing station.30 The GTS consisted of 3 components: A Dexcom G4 CGM system (Dexcom, San Diego, Ca), an iPhone and an iPad (Figure 1).30 Using Dexcom software applications (Share and Follow) and a commercially available internet network, glucose values were transmitted initially from the CGM receiver to the iPhone, both located at the patients’ bedside, and then finally to the iPad located at the nursing station. We conducted a pilot study which evaluated the use of the GTS in the noncritical/non-ICU setting. The GTS system’s low glucose threshold was set at 85 mg/dL, at which point an alert was triggered activating the hypoglycemia prevention protocol. Nursing staff were trained to respond to low glucose alerts from the iPad and take preventative action for impending hypoglycemia.

Figure 1.

Description of Glucose Telemetry System (GTS).30

Two subjects had a total of 3 low glucose threshold alarm events, resulting in hypoglycemia preventive actions. Two subjects experienced hypoglycemic events due to receipt of prandial insulin and then transfer off the floor resulting in a missed meal in one case, and poor nutritional intake in the second case. Use of a GTS with a simplified hypoglycemia prevention protocol may propose a strategy for reducing hypoglycemia among hospitalized patients. However, the continued hypoglycemia observed despite these interventions reveals the potential challenges of implementing such a system in an inpatient setting, warranting further investigation.

Non-ICU Closed-Loop Studies

Though closed-loop systems are not yet commercially available, few studies have evaluated use in the inpatient setting mostly in the critical care setting or the perioperative period31-33 (Table 2). More recently closed-loop systems have also been evaluated in the non-ICU setting. In an innovative, single center, open-label, parallel group, clinical trial, 40 participants with T2DM were randomized either to a closed-loop insulin delivery system or to conventional subcutaneous insulin delivery, with an overall observation period of 72 hours.34 The proportion of time spent in target range (100-180 mg/dl) was 59.8% ± 18.7 in the closed-loop group and 38.1% ± 16.7 in the control group (P = .0004). No episodes of severe hypoglycemia occurred in either group. More than 85% of the participants in the closed-loop reported satisfaction with their overall glycemic control during their hospitalization. Bally et al conducted a larger multicenter study that involved 136 adults with T2DM and followed participants for a longer duration through hospital discharge (for up to 15 days).35 Subjects randomized to the closed-loop system had better overall glycemic control. The proportion of time spent in target range (100-180 mg/dl) was 65.7% ± 16.8 in the closed-loop group and 41.5% ± 16.9 in the control group (P < .0001). There was no significant difference in the duration of clinically significant hypoglycemia (defined as glucose <54 mg/dl; P = .80) or in the amount of insulin that was administrated (median dose, 44.4 and 40.2 units; P = .50). Notably, the group of subjects randomized to the closed-loop system did not receive prandial insulin bolus. In addition, the timing or carbohydrate content of the meals were not included in the software control algorithm. Overall, this is a groundbreaking clinical trial using a closed-loop insulin delivery system resulting in significantly improved glycemic control, without a higher risk for hypoglycemia.

Table 2.

Closed-Loop Systems Used in Non-ICU Setting.

| Ref | Service | Diabetes technology | # patients | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37 | General wards | CL (Dana R Diabecare IP and Abbott Freestyle Navigator II CGM) vs blinded CGM Abbott Freestyle Navigator II and MDI | T2DM = 40 | Time spent in target range was better in the CL group vs control group (59.8% ± 18.7 vs 38.1% ± 16.7; P = .0004). No episodes of severe hypoglycemia occurred in either group. Participants were followed up to 72 h. |

| 38 | General wards | CL (Dana R Diabecare IP and Abbott Freestyle Navigator II CGM) vs blinded CGM Abbott Freestyle Navigator II and MDI. | T2DM = 136 | Time spent in target range was better in the CL group vs control group (65.7% ± 16.8 vs 41.5% ± 16.9, P < .0001). No significant difference in the duration of time in clinically significant hypoglycemia (P = .50). Participants were followed until hospital discharge. |

CGM: Continuous Glucose Monitoring; T2DM: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; MDI: multiple daily injections; CL: Closed-loop insulin delivery system.

Advantages and Limitations of CGM and Closed-Loop Systems in the Non-ICU Setting

Use of CGM in the non-ICU setting may offer several advantages over standard POC glucose testing (Table 3). As sensor glucose is automatically measured every few minutes, glucose monitoring would occur on a continuous basis without the expense of increased manpower. Some newer CGM devices have eliminated the need for blood glucose calibrations. Therefore, the use of CGM has the potential to decrease nursing workload. It is estimated that each POC blood glucose check requires 5 minutes to perform.21 Thus, greater frequency of monitoring with POC testing cannot be achieved without increasing nursing workload. This is a notable advantage in the non-ICU setting with the generally lower nursing-to-patient ratios when compared to the ICU setting.36 CGM provides significantly more data to evaluate and also provides direction of glucose change, magnitude of change, and predictive and actual hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia event warnings. CGM systems also report glucose variability, which is an important metric to evaluate while inpatient to reduce risk of adverse outcomes.15 This information is not attainable with POC blood glucose testing which provides only a snapshot of glycemic control. Despite these benefits, a current limitation for implementation is the lack of FDA approval to use CGM data for treatment decisions in the inpatient setting. Therefore, insulin dosing should continue to be based on POC blood glucose testing.

Table 3.

Advantages and Limitations of Closed-Loop and CGM Systems.

| Potential advantages | Potential limitations | |

|---|---|---|

| Closed-loop system* | Improve glycemic control Reduce nursing workload due to automated insulin delivery and continuous interstitial glucose measurements Improve patient satisfaction |

Novel technology necessitating involvement from endocrinology

service limiting widespread adoption Need for routine monitoring for infusion site issues and adequate insulin supply in reservoir Conversion to alternative mode of insulin delivery in the event of insulin pump malfunction may be difficult due to unclear insulin requirements |

| CGM systems | Increase frequency of glucose monitoring (every few

minutes) Provide data on glucose variability, magnitude of glucose change, and real-time direction of change Predictive and actual hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia alarms Greater rate of detection for hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia |

Lack of FDA approval for inpatient use Cost-prohibitive (cost of supplies, maintenance and training required) Lack of hospital infrastructure supporting inpatient use Contraindication/caution with use during imaging studies General hospital staff unfamiliarity with CGM leading to misinterpretation of data Few hours of unavailable CGM data during sensor warm-up period at start of new sensor session Sensor drift and need for blood glucose calibration requirement depending on CGM system Potential interference with glucose accuracy from medications and substances (acetaminophen, heparin, salicylic acid, dopamine, uric acid, ascorbic acid, maltose, and mannitol, tissue deposits) Sensor lag leading to delayed detection of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia |

CGM: continuous glucose monitoring; CSII: continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; FDA: Food Drug Administration.

Closed-loop system would also include advantages/limitations listed for CGM use.

Some limitations of CGM use in the non-ICU setting stem from the lack of safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness analyses at present time. Use of CGM technology in the inpatient setting is largely investigational. Experience is often limited to endocrinologists and other health care professionals with specialized training. The general unfamiliarity with CGM systems would require investment of time and resources for provider and nursing training in the non-ICU setting. Training should include an overview of technical aspects of a CGM system, sensor insertion, as well as interpretation of CGM data. Untrained providers may misinterpret CGM data, which may lead to frequent insulin administration increasing risk of stacking.21 Hospitals without an endocrinology service would be more challenged to integrate this technology for inpatient management of diabetes.

There are several factors influencing sensor glucose accuracy. Potential interferences by medications and substances could lead to potential inaccurate sensor glucose measurements. As acetaminophen particularly is a frequently administered medication in the non-ICU setting, this would be a significant limitation. Sensor drift increases risk of inaccuracy across the life of a sensor session, resulting in the need for blood glucose calibrations for several CGM systems. Newer CGM devices, such as Dexcom G6 (Dexcom, San Diego, CA) and Abbott Freestyle Libre (Abbott Diabetes Care, Alameda, CA), have improved sensor design which has eliminated interference by acetaminophen and the need for blood glucose calibration. As CGM sensors measure interstitial glucose versus plasma glucose there is a delay or lag time in reporting based on the different rates of change in those two compartments.37 The effect of this lag time is most pronounced in periods of rapidly shifting glucose. This could result in delayed detection of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia with CGM use. There are several potential situations where CGM may not be available or not recommended. This can include when patients exhibit changes in tissue perfusion potentially leading to inaccurate interstitial glucose measurements, or during sensor warm-up period where data are unavailable for hours.

Using a closed-loop system or “artificial pancreas” in the hospital setting might be more feasible and improve on some of the limitations of using sensor-augmented insulin pumps. Nursing staff would have limited interaction after the closed-loop system is in place given the insulin delivery is automated by the insulin pump based on the predictive control algorithm. The use of such technologies would possibly allow for a reduction in nursing workload while improving glycemic control. A closed-loop system that fully automates insulin delivery would allow for more precise insulin dosing that may better meet the needs of an inpatient due to acute changes in stress, renal function, infections, nutritional intake, or use of steroids. The potential improved glycemic control using closed-loop systems may also increase patient satisfaction.

Given the novelty of this technology, there would be a significant amount of unfamiliarity with its use. Hospital staff would require training regarding technical aspects and trouble-shooting. Routine monitoring of infusion sites would be required to detect any inflammation or infection that could lead to severe hyperglycemia. Regular inspection of the insulin pump’s insulin reservoir to avoid abrupt cessation in continuous insulin infusion is also necessary. In the event of insulin pump malfunction or change in patient’s clinical status, patients would need to be converted to a basal-bolus MDI regimen or insulin drip depending on clinical status. This conversion could be more challenging when using a closed-loop system as insulin dosing requirements are less clear. The use of closed-loop systems in the non-ICU setting would need the involvement of an endocrinology team, which would limit widespread adoption in institutions without this service.

Limitations to initiation of insulin pumps while inpatient may also include the complexity of patients with diabetes that exhibit multiple comorbidities and have complicated medical admissions, as well as the time required to provide comprehensive insulin pump training to providers and nursing staff. There is also a lack of infrastructure to support closed-loop systems within the EMR, policies to reduce liability of insulin pump use while inpatient, as well as the need for cybersecurity protections. There may also be concerns with interpatient reuse of the closed-loop medical devices. The disposable components of a closed-loop system include the infusion sets, reservoirs, and sensors, which are the components of the system that come in contact with subcutaneous tissue and bodily fluid. Policies and procedures are needed to ensure appropriate disinfection of reusable components such as the transmitters and insulin pumps. Last, similarly with CGM use there is limited safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness evaluations at present time in the non-ICU setting.

Historically, continued CGM and insulin pump use during magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computerized-tomography (CT) scan were contraindicated. In February 2018, the FDA released an update indicating receipt of a small number of reports of adverse events related to CT exposure with insulin pumps (including CGM or sensor-augmented pumps), with no evidence of direct causation.38 Overall, they stated the probability of an adverse event with CT exposure is low. CGM and insulin pump product guides still recommend avoidance of CT exposure at present time.39-41 There is a need for larger direct causality safety studies before a definitive conclusion can be made regarding risk of exposure. In the absence of this, providers and patients should use caution when deciding whether to expose a CGM device and insulin pump to CT. There are strategies proposed to mitigate CT exposure risk if the device is not disconnected, such as use of a lead apron to cover the device.42

Future Directions

Future CGM design should not be vulnerable to exposure from routine imaging studies frequently performed while inpatient or hospital policies should be implemented to avoid medical errors. The ideal CGM sensors should have minimal interference with medications,21 especially with those that are commonly prescribed in the hospital. In addition, CGM systems should require fewer or no blood glucose calibrations, increasing ease of use for nursing staff. Recent advancements in CGM technology include improvement in glucose sensor accuracy which has reduced or eliminated the need for blood glucose calibrations, as well as changes to the sensor membrane which can now protect against interference by commonly used medications such as acetaminophen, frequently prescribed among hospitalized patients.42,43

As treatment decisions will be made automatically by the closed-loop systems, these devices will be susceptible to medical hacking. An insulin pump or CGM could be hacked to either increase or suspend insulin infusion leading to potentially lethal hypoglycemic events or episodes of diabetes ketoacidosis. These types of cybersecurity concerns have been raised and efforts to develop cybersecurity protection against these extreme scenarios should be initiated.44,45

Hospitalized DM patients represent a vulnerable population frequently admitted with severe medical conditions. Hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, and glucose variability while admitted increases risk for adverse outcomes, length of stay, and mortality.2,7-11 We believe future management of diabetes among hospitalized patients will include use of diabetes technology for glucose monitoring and insulin delivery. More specifically, it may include the use of CGM integration with closed-loop insulin pump systems, where glucometric values are projected to a centralized location allowing CGM and insulin dosing determined and delivered by automation. To become a reality, CGM and closed-loop systems need to be evaluated extensively in the inpatient setting and receive necessary FDA approvals, as these systems are still considered investigational at present time. It is also important to consider that implementation of this type of technology may increase hospital-related expenses, therefore cost-effectiveness analyses will be necessary. The use of computerized decision support and glucose management systems using POC or potentially CGM glucose values to adjust insulin may present a pragmatic next step in inpatient diabetes management.46

Regardless of the insulin treatment modality used in the hospital setting, we believe the wireless and continuous transmission of glucometric values to a device at the nursing station would allow providers and nursing staff to detect early episodes of impending hypoglycemia or severe uncorrected hyperglycemia that require immediate treatment, improving patient safety and reducing morbidity and mortality.

Conclusion

Due to the scarcity of clinical evidence, the use of CGM systems either alone or integrated with insulin pumps in the non-ICU setting is still considered investigational. Large randomized clinical trials are needed with a “pragmatic” evaluation of the use of CGM in an inpatient setting, hopefully proving the necessity of the above systems. As diabetes technology continues to evolve, we believe future management of hospitalized patients with DM will include use of CGM systems where glucometric values are transmitted wirelessly to a monitoring device located at the nursing station, resembling current cardiac telemetry systems, with automated insulin delivery.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; CL, closed-loop insulin delivery system; CSII, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; CT, computerized tomography; DM, diabetes mellitus; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; GTS, Glucose Telemetry System; ICU, intensive care unit; IP, insulin pump; MDI, multiple daily injections; POC, point of care; RT, real time; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: MW and LGS declare that they have no conflicts of interest. EKS has received CGM supplies from Dexcom for the conduction of inpatient clinical trials.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported in part by the VA MERIT award (#1I01CX001825-01) from the US Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences Research and Development Service. The contents do not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

ORCID iD: Elias K. Spanakis  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9352-7172

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9352-7172

References

- 1. Garber AJ, Moghissi ES, Bransome ED, et al. American College of Endocrinology position statement on inpatient diabetes and metabolic control. Endocr Pract. 2004;10:77-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Umpierrez GE, Isaacs SD, Bazargan N, You X, Thaler LM, Kitabchi AE. Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in-hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:978-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jiang HJ, Stryer D, Friedman B, Andrews R. Multiple hospitalizations for patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1421-1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:917-928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cook CB, Kongable GL, Potter DJ, Abad VJ, Leija DE, Anderson M. Inpatient glucose control: a glycemic survey of 126 U.S. hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:E7-E14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Swanson CM, Potter DJ, Kongable GL, Cook CB. Update on inpatient glycemic control in hospitals in the United States. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:853-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baker EH, Janaway CH, Philips BJ, et al. Hyperglycaemia is associated with poor outcomes in patients admitted to hospital with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2006;61:284-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McAlister FA, Majumdar SR, Blitz S, Rowe BH, Romney J, Marrie TJ. The relation between hyperglycemia and outcomes in 2,471 patients admitted to the hospital with community-acquired pneumonia. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:810-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McAlister FA, Man J, Bistritz L, Amad H, Tandon P. Diabetes and coronary artery bypass surgery: an examination of perioperative glycemic control and outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1518-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Golden SH, Peart-Vigilance C, Kao WH, Brancati FL. Perioperative glycemic control and the risk of infectious complications in a cohort of adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1408-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Umpierrez GE, Hellman R, Korytkowski MT, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in non-critical care setting: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:16-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Akirov A, Grossman A, Shochat T, Shimon I, et al. Mortality among hospitalized patients with hypoglycemia: insulin related and noninsulin related. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:416-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Curkendall SM, Natoli JL, Alexander CM, Nathanson BH, Haidar T, Dubois RW. Economic and clinical impact of inpatient diabetic hypoglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2009;15:302-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Turchin A, Matheny ME, Shubina M, Scanlon JV, Greenwood B, Pendergrass ML. Hypoglycemia and clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes hospitalized in the general ward. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1153-1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mendez CE, Mok KT, Ata A, Tanenberg RJ, Calles-Escandon J, Umpierrez GE. Increased glycemic variability is independently associated with length of stay and mortality in noncritically ill hospitalized patients. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:4091-4097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Expands Indication for Continuous Glucose Monitoring System, First to Replace Fingerstick Testing for Diabetes Treatment Decisions. Rockville, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2016. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm534056.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 17. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Continuous Glucose Monitoring System for Adults Not Requiring Blood Sample Calibration. Rockville, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2017. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm577890.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 18. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Authorizes First Fully Interoperable Continuous Glucose Monitoring System, Streamlines Review Pathway for Similar Devices. Rockville, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2018. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm602870.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beck RW, Riddlesworth T, Ruedy K, et al. Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes using insulin injections: the DIAMOND randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:371-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beck RW, Riddlesworth TD, Ruedy K, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring versus usual care in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving multiple daily insulin injections: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:365-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wallia A, Umpierrez GE, Rushakoff RJ, et al. Consensus statement on inpatient use of continuous glucose monitoring. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;11:1036-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Preiser JC, Chase JG, Hovorka R, et al. Glucose control in the ICU: a continuing story. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2016;10:1372-1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levitt DL, Silver KD, Spanakis EK. Inpatient continuous glucose monitoring and glycemic outcomes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;1932296817698499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. US Food and Drug Administration. The Artificial Pancreas Device System. Rockville, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2018. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/productsandmedicalprocedures/homehealthandconsumer/consumerproducts/artificialpancreas/default.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burt MG, Roberts GW, Aguilar-Loza NR, Stranks SN. Brief report: comparison of continuous glucose monitoring and finger-prick blood glucose levels in hospitalized patients administered basal-bolus insulin. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2013;15:241-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schaupp L, Donsa K, Neubauer KM, et al. Taking a closer look—continuous glucose monitoring in non-critically ill hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus under basal-bolus insulin therapy. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17:611-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gomez AM, Umpierrez GE, Muñoz OM, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring versus capillary point-of-care testing for inpatient glycemic control in type 2 diabetes patients hospitalized in the general ward and treated with a basal bolus insulin regimen. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2015;10:325-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Levitt DL, Silver KD, Spanakis EK. Inpatient continuous glucose monitoring and glycemic outcomes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;11:1028-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levitt DL, Silver KD, Spanakis EK. Mitigating severe hypoglycemia by initiating inpatient continuous glucose monitoring for type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;11:440-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Spanakis EK, Levitt DL, Siddiqui T, et al. The effect of continuous glucose monitoring in preventing inpatient hypoglycemia in general wards: the glucose telemetry system. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12:20-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mibu K, Yatabe T, Hanazaki K. Blood glucose control using an artificial pancreas reduces the workload of ICU nurses. J Artif Organs. 2012;15:71-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Okabayashi T, Shima Y, Sumiyoshi T, et al. Intensive versus intermediate glucose control in surgical intensive care unit patients. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1516-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Namikawa T, Munekage M, Kitagawa H, et al. Comparison between a novel and conventional artificial pancreas for perioperative glycemic control using a closed-loop system. J Artif Organs. 2017;20:84-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thabit H, Hartnell S, Allen JM, et al. Closed-loop insulin delivery in inpatients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, parallel-group trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:117-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bally L, Thabit H, Hartnell S, et al. Closed-loop insulin delivery for glycemic control in noncritical care. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:547-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thabit H, Hovorka R. Bridging technology and clinical practice: innovating inpatient hyperglycaemia management in non-critical care settings. Diabet Med. 2018;35:460-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schmelzeisen-Redeker G Schoemaker M Kirchsteiger H Freckmann G Heinemann L Del Re L. Time delay of CGM sensors: relevance, causes, and countermeasures. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2015;9:1006-1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. US Food and Drug Administration. Interference between CT and Electronic Medical Devices. Rockville, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2018. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/radiation-emittingproducts/radiationsafety/electromagneticcompatibilityemc/ucm489704.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tandem Diabetes Care. Important Safety Information—t:slim X2™ Insulin Pump with Basal-IQ™ Technology. 2018. Available at: https://www.tandemdiabetes.com/important-safety-information.

- 40. Medtronic. Important Safety Information. 2018. Available at: https://www.medtronicdiabetes.com/important-safety-information.

- 41. Dexcom. Continuous Glucose Monitoring Safety Information. 2018. Available at: https://www.dexcom.com/safety-information.

- 42. Umpierrez GE, Klonoff DC. Diabetes technology update: use of insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitoring in the hospital. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1579-1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rodbard D. Continuous glucose monitoring: a review of recent studies demonstrating improved glycemic outcomes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2017;19:S25-S37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Klonoff DC, Kleidermacher DN. Now is the time for a cybersecurity standard for connected diabetes devices. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2016;10:623-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Armstrong DG, Kleidermacher DN, Klonoff DC, Slepian MJ. Cybersecurity regulation of wireless devices for performance and assurance in the age of “medjacking.” J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2015;10:435-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Aloi J, Bode BW, Ullal J, et al. Comparison of an electronic glycemic management system versus provider-managed subcutaneous basal bolus insulin therapy in the hospital setting. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;11:12-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]