Abstract

Rationale:

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are an important class of drugs in managing cardiovascular diseases. Patients usually rely on these medications for the remainder of their lives after diagnosis. Although the acute pharmacological actions of CCBs in the hearts are well-defined, little is known about the drug-specific effects on human cardiomyocyte transcriptomes and physiological alterations after long-term exposure.

Objective:

This study aimed to simulate chronic CCB treatment and to examine both the functional and transcriptomic changes in human cardiomyocytes.

Methods and Results:

We differentiated cardiomyocytes and generated engineered heart tissues from three human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines and exposed them to four different CCBs—nifedipine, amlodipine, diltiazem, and verapamil—at their physiological serum concentrations for two weeks. Without inducing cell death and damage to myofilament structure, CCBs elicited line-specific inhibition on calcium kinetics and contractility. While all four CCBs exerted similar inhibition on calcium kinetics, verapamil applied the strongest inhibition on cardiomyocyte contractile function. By profiling cardiomyocyte transcriptome after CCB treatment, we identified little overlap in their transcriptome signatures. Verapamil is the only inhibitor that reduced the expression of contraction-related genes, such as myosin heavy chain and troponin I, consistent with its depressive effects on contractile function. The reduction of these contraction related genes may also explain the responsiveness of HCM patients to verapamil in managing left ventricular outflow tract obstruction.

Conclusions:

This is the first study to identify the transcriptome signatures of different CCBs in human cardiomyocytes. The distinct gene expression patterns suggest that although the four inhibitors act on the same target, they may have distinct effects on normal cardiac cell physiology.

Keywords: Cellular Reprogramming, Electrophysiology, Stem Cells, Induced pluripotent stem cells, myocytes, calcium channel blockers, computational biology, contractility

INTRODUCTION

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are a group of structurally diverse compounds that interfere with the L-type calcium channel. Since its discovery in the 1960’s1,2, this drug class has been important in managing cardiovascular disease, especially for hypertension3. It is reported that CCBs constituted 13% of the $28.2 billion total annual sales in anti-hypertensive drugs4. Many hypertensive patients are prescribed CCBs to control blood pressure over their lifetime. Thus, given the number of users and the length of the treatment, it is important to understand the whole spectrum of physiological and transcriptomic effects elicited by long-term CCB exposure.

Calcium channel blockers are broadly classified into two classes, dihydropyridine and non-dihydropyridine inhibitors, based on the chemical structure. While all CCBs can lower blood pressure, dihydropyridine inhibitors such as nifedipine and amlodipine are generally used in hypertension management as they preferentially act on vascular calcium channels3,5,6. The restriction of calcium entry into smooth muscle cells limits the activation of myosin light chain phosphorylation, thus preventing smooth muscle contraction and dilating blood vessels7. Although dihydropyridine CCBs show selectivity towards smooth muscle cells, they can still act on the calcium channels in cardiac cells, as demonstrated by various studies6,8.

On the other hand, non-dihydropyridine inhibitors, such as diltiazem and verapamil, show more myocardial preference and therefore are more often used in arrhythmia, angina, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) patients6. Calcium is an essential messenger for cardiac excitation-contraction coupling (E-C coupling). Membrane depolarization triggers the opening of calcium channel and the subsequent calcium entry induces the opening of ryanodine receptor, the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) calcium channel. Calcium released from the SR binds to troponin C, which in turn initiates contraction9,10. Blocking the calcium entry can slow heart rate and reduce cardiac contractility, which are beneficial in the management of arrhythmia and angina pain. However, because calcium is crucially involved in various cellular processes in cardiomyocytes, interfering with calcium entry may elicit calcium-sensitive signaling elements11–13. In particular, reducing calcium channel activity by downregulating the protein expression has been shown to induce cardiac hypertrophy through calcineurin-dependent mechanism in mice14. With many hypertensive patients being prescribed CCBs for the remainder of their lifetime to manage blood pressure, it is vital to answer crucial questions on the long-term effect of CCB usage on myocardial function. At present, there is a major knowledge gap on how long-term blockade of calcium channel activity may affect human cardiomyocyte transcriptome and, subsequently, cell homeostasis.

With the pivotal discovery of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology and improved cardiomyocyte differentiation protocols15,16, we are now able to explore how a given drug alters the human cardiomyocyte transcriptome. Using human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) and engineered heart tissues (EHTs)17, we were able to identify patient-specific responses to chronic exposure of four commonly used CCBs (nifedipine, amlodipine, diltiazem, and verapamil). We also identified the drug-specific transcriptome signature for each CCB, which is associated with the alteration in contractile performance of cardiomyocytes. Furthermore, our transcriptomic findings identify genes that may predict the responsiveness of obstructive HCM patient to verapamil treatment. Collectively, this study provides comprehensive information on how chronic CCB treatment can potentially affect human cardiomyocyte transcriptome and function.

METHODS

Detailed Methods section is available in the Online Data Supplement. RNA-Seq data is publicly available with GEO accession number GSE129793.

RESULTS

Chronic L-type calcium channel blocker treatment inhibited contractility and calcium kinetics, without affecting cardiomyocyte survival and myofilament structure.

Human iPSCs from three healthy individuals of different genetic backgrounds (Online Table I) were differentiated into cardiomyocytes. To simulate the chronic CCB exposure in human patients, iPSC-CMs were treated for two weeks with nifedipine, amlodipine, diltiazem, and verapamil at their respective therapeutic plasma concentrations6,18,19 (Figure 1A). We first sought to determine if the dose and duration of treatment were suitable for profiling transcriptome changes in human cardiomyocytes. Because calcium entry is important for E-C coupling, the contractile performance was monitored by the motion tracking system20. Upon 30-minute exposure, reductions in beating rate and contraction velocities were observed (Online Figures I and II), consistent with the pharmacological action on cardiomyocytes. In the case of verapamil, we also observed a subset of cells showing higher beating rate. To further validate the inhibition on calcium channel by verapamil, we next performed microelectrode array (MEA) to examine the field potential duration (FPD) as an indicator of action potential duration (APD). When the calcium channel is inhibited, the action potential should be shortened. In all lines, FPD was shortened at the therapeutic concentration (Online Figure III). Thus, these concentrations appeared to interfere with the calcium channel function and recapitulate the physiological effect in iPSC-CMs.

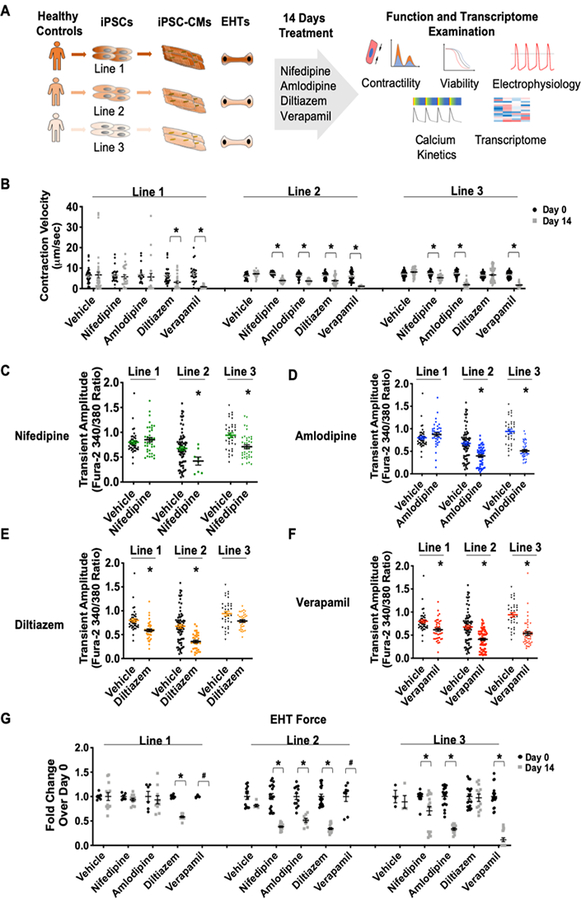

Figure 1. Treatment of calcium channel blockers inhibited cardiomyocyte contractility and calcium kinetics.

(A) Schematic outline of study design. iPSCs were derived from three healthy individuals and differentiated into iPSC-CMs. After a 14-day treatment of CCB, iPSC-CMs were subjected to functional assessment and transcriptome analysis. (B) iPSC-CMs showed reduced contraction velocity after 14 days of CCB treatment (nifedipine 433 nmol/L, amlodipine 39 nmol/L, diltiazem 443 nmol/L, verapamil 814 nmol/L). *p<0.05 vs. vehicle or its respective Day 0 value (n=20–30). (C-F) Calcium transient amplitude was reduced after chronic CCB treatment. *p<0.05 vs. its respective vehicle control (n=40). (G) The same line-specific and drug-specific effects were observed when we measured the change of force generated by engineered heart tissue of each line. The force generation after verapamil treatment in lines 1 and 2 were below detection threshold. *p<0.05 vs. its respective Day 0 value (n=3–18)

As all four CCBs have safe pharmacological profiles, the treatment length and dose should not induce significant cell death. After assessing both NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductase activity and ATP content, all four drugs were not found to elicit a pro-death response. As a positive control, a therapeutic dose of a cardiotoxic chemotherapy agent, doxorubicin21,22, caused significant cell loss in all lines that were treated (Online Figure IV). Next, we examined the myofilament structure through troponin T (TNNT2) and α-actinin staining. Cardiomyocytes treated with CCBs displayed a normal structure (Online Figure V), indicating that the length and dose of CCB treatment did not inflict permanent damage to cardiomyocytes.

After 14-day of CCB treatment, cardiomyocytes in general demonstrated weaker contraction and relaxation, with verapamil exhibiting the greatest inhibition (Figures 1B and Online Figure VI). CCB-treated cells generally showed a lower transient amplitude (Figures 1C–F) and prolonged cytosolic calcium decay (Online Figure VII), indicating that less calcium was available for each contraction as well as slower calcium removal for relaxation. Thus, the inhibition in contraction and relaxation can be at least partially attributed to slower calcium kinetics.

iPSC-CMs exhibited line-specific and drug-specific response upon chronic CCB treatment.

It should be noted that each line has its specific response to each antagonist. After two weeks of dihydropyridine CCB treatment, healthy control line 1 showed recovery in contraction and relaxation, while the other two lines demonstrated reduction (Figure 1B and Online Figure VII). Cardiomyocytes from control line 1 did not show inhibition in calcium kinetics (Figures 1CߝD and Online Figure VII) after nifedipine and amlodipine treatment. By comparison, line 3 did not exhibit alteration in contraction and relaxation upon diltiazem treatment (Figure 1B and Online Figure VII), which was also reflected in calcium imaging (Figures 1F and Online Figure VII). These findings suggest that each line has a specific response in recovery from the inhibition imposed by CCB.

We next extended our studies to a 3-D model by fabricating line-specific engineered heart tissue (EHT)23,24. Consistently, we observe the same line-specific and drug-specific effects when we examined the force generation. EHT of line 1 showed a resistance to dihydropyridine blockade, while EHT of line 3 showed a diltiazem-specific resistance (Figure 1G). Thus, the drug-specific effect was consistently manifested in both 2-D and 3-D tissue models.

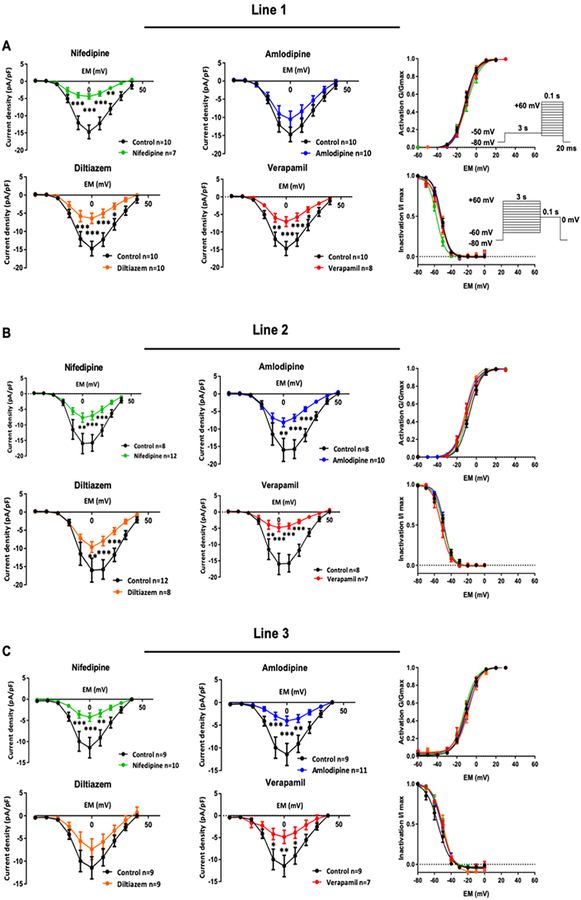

To further understand how CCBs elicit different effect on each iPSC-CM line, we next performed extensive electrophysiological investigation to characterize the L-type calcium channel and its resulting current ICaL. First, we performed voltage-clamp recordings to evaluate the action potential (AP) of each investigated line. AP parameters showed that the majority of iPSC-CMs were ventricular-like (Online Figure VIII). By measuring ICaL after chronic drug treatment (Online Figure IX), we showed that the line-specific and drug-specific recovery may be linked to the resistance of sarcolemmal calcium channels to CCB inhibition. Cardiomyocytes from line 1 exhibited recovery from dihydropyridine CCB inhibition in contractility and calcium kinetics. Although nifedipine caused a persistent blockade of ICaL, no significant inhibition was observed on the calcium current in this line upon chronic amlodipine treatment (Figure 2A). Calcium current of cardiomyocytes from line 3 was not affected by diltiazem (Figure 2C), which was consistent with the contractility and the calcium data. All drugs were functional as they all exerted a significant inhibition on line 2 (Figure 2B), the line that demonstrated inhibition by all four drugs in our functional assays. It should also be noted that all drugs effectively blocked the calcium entry without altering the gating properties of ICaL, as indicated by lack of changes in the activation and inactivation kinetics. These findings suggest that the calcium channels at the sarcolemma might develop resistance for certain CCB binding, contributing to the line-specific response.

Figure 2. Line-specific and drug-specific response of calcium channel blockade was observed.

(A) Characterization of calcium channel properties upon chronic CCB treatment in Line 31. Amlodipine did not exert significant blockade of calcium current, as indicated by current-voltage curve. (B) All four CCBs inhibited calcium current in Line 2. (C) Diltiazem was the only CCB that did not exert significant blockade of calcium current in Line 3. No drugs altered the activation and inactivation properties of calcium channel. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs. vehicle.

Different L-type calcium channel blocker exerted specific transcriptomic changes.

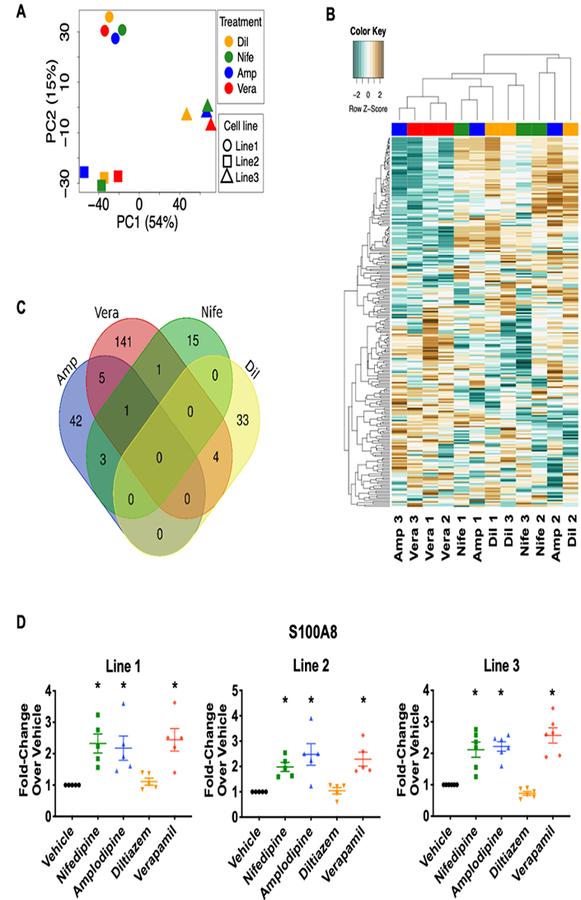

The dose and the length of drug treatment exerted the expected effects on contractility and calcium kinetics. We then performed RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) to examine the transcriptome change induced by each CCB. Principal component analysis (PCA) showed that genetic background constituted most of the differences, as samples from the same line clustered closely together (Figure 3A). Using the fold-change over vehicle control, we performed the unsupervised hierarchical clustering and found that only verapamil-treated samples were grouped together, suggesting weaker transcriptome effects by the other three CCBs (Figure 3B). When we closely examined the genes that were altered in all lines, we did not find any genes that were regulated simultaneously by all four treatments (Figure 3C). Only one gene, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A8 (S100A8), a calcium- and zinc-binding protein that has been indicated in cardiac hypertrophy, endotoxin- and doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy25–27, was upregulated by nifedipine, amlodipine, and verapamil treatments. This was also seen in western blot analysis (Figure 3D). The overall results indicate that these four CCBs had their own distinctive transcriptome signatures with little overlapping, though all of them exerted similar acute effects and mechanistically hit the same pharmacological target in cardiomyocytes.

Figure 3. Four calcium channel blockers had little overlapping in their transcriptome signatures.

. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) showed that most of the transcriptomic difference was related to genetic makeup of the iPSC lines. (B) Unsupervised clustering showed that verapamil-treated lines were clustered together. (C) Venn diagram of genes that were induced by CCBs revealed little overlapping among the four treatments. Only one gene, S100A8, was shared by three CCBs. (D) S100A8 protein expression was induced by nifedipine, amlodipine, and verapamil. Representative western blot images are shown in Online Figure X. *p<0.05 vs. vehicle (n=5–6).

Of the four CCBs, nifedipine exerted the least amount of alterations in terms of gene numbers (Online Tables III and IV), most of which not coding for proteins (Online Figure XIA). By contrast, the other dihydropyridine inhibitor, amlodipine, induced a broader transcriptome alteration. A total of 51 genes were altered in all three lines and more than 43% were protein-coding genes (Online Figure XIB). Gene-Ontology (GO) analysis indicated that the ubiquitin-like modifier FAT10 activating enzyme activity is highly implicated in both nifedipine and amlodipine treatments (Online Figures XIC and XID). Long-term application of these two dihydropyridine blockers induced the expression of ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 6 (UBA6, Online Figure XII and Online Table IV), an enzyme that is essential for FAT10 activity, which was also seen in immunoblotting (Online Figure XIE). It should be noted that nifedipine and amlodipine, but not diltiazem or verapamil, induced the expression of UBA6. Thus, it appears that long-term use of dihydropyridine CCBs may specifically affect the ubiquitin-proteasomal pathways in the heart.

Chronic verapamil treatment down-regulates muscle contraction related genes.

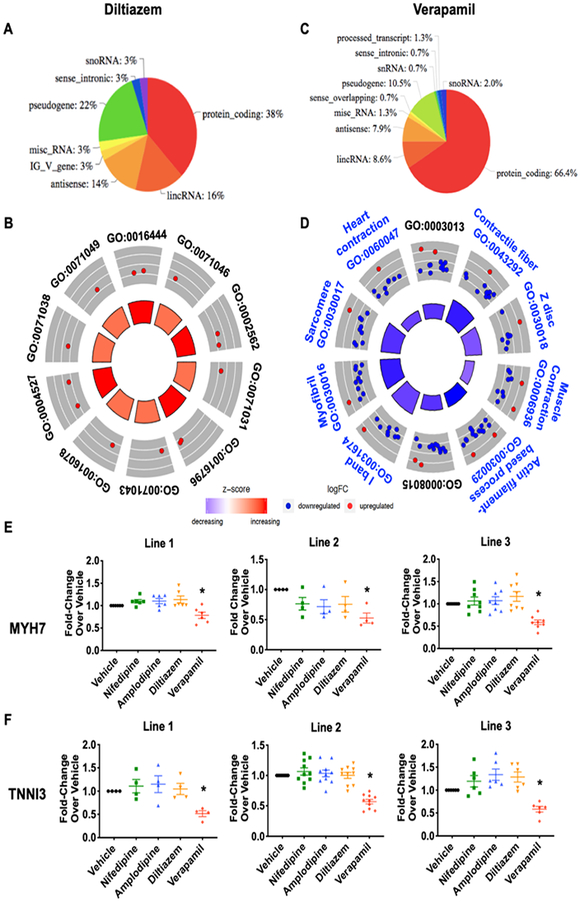

Diltiazem belongs to the benzodiazepine class of CCB that can be used to treat arrhythmia and angina pain. In our study, diltiazem treatment affected 37 genes in all three lines, with 38% of them being protein-coding genes (Figure 4A). Compared to the other three CCBs, diltiazem exerted a very distinct effect on the cardiomyocyte transcriptome. It did not share any genes with the dihydropyridine blockers, and only 4 non-protein-coding genes were overlapped with verapamil (Figure 3C). Although GO analysis shows that RNA processing-related pathways were highly implicated (Figure 4B and Online Table V), the related genes were not cardiac-specific (Online Figure XII), and we were unable to detect protein expression. Overall, the chronic treatment of diltiazem at the physiological serum concentration did not appear to affect the expression of genes that are key to cardiomyocyte function.

Figure 4. Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers showed distinct transcriptome patterns.

(A) Protein-coding genes contributes to 38% of the total changes after diltiazem treatment. (B) GO analysis revealed top 10 cellular processes that were implicated in diltiazem treatment. (C) Protein-coding genes made up of 66% of the total changes after verapamil treatment. (D) GO analysis revealed top 10 cellular processes that were implicated in verapamil treatment. Cardiac related pathways are in blue font. (E) MYH7 and (F) TNNI3 protein expression was reduced specifically after verapamil treatment. Representative western blot images are shown in Online Figure X. *p>0.05 vs. vehicle (n=4–10).

Similar to diltiazem, verapamil is used for controlling heart rate in supraventricular tachycardia and relieving angina due to its negative inotropic action3. RNA-seq analysis revealed that the continuous use of verapamil significantly altered the expression of 148 genes, with 66% of these genes coding for proteins (Figure 4C). In contrast to the other CCBs, verapamil caused more gene down-regulation than induction (Figure 4D and Online Figure XII). Moreover, a set of cardiac contraction-related genes were significantly down-regulated, which was not seen in other CCB treatments. GO analysis revealed that myofibril and sarcomeric structure-related pathways were significantly affected (Figure 4D). Using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis to cluster genes with disease implication, hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies were specifically suggested (Online Figure XIIIA). Among the down-regulated genes, myosin heavy chain 7 (MYH7), cardiac troponin I (TNNI3), and Desmin are particularly known to be associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Online Figure XIIIB) as disease-causing mutations have been identified28.

To further verify the alterations induced by verapamil, we focused on the expression of proteins that showed a reduction in mRNA transcript levels. The expression of MYH7 and TNNI3 was consistently and significantly reduced in verapamil-treated cardiomyocytes (Figures 4EߝF), whereas other sarcomeric proteins such as myosin heavy chain 6 (MYH6) and TNNT2 were not altered (Online Figures XIVAߝB). The level of P-type cation transport ATPase ATP1A2, a member of sodium/potassium ATPase, was reduced (Online Figure XIVC), but another P-type ATPase, ATP2A2 or Sarcoplasmic/Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium ATPase 2 (SERCA2), remained unchanged (Online Figure XIVD). These specific changes were only observed in verapamil treatment, suggesting the selectivity of this CCB on modulating cardiac contractile function. The down-regulation of sarcomeric genes also supports the extra inhibition observed in the motion tracking analysis, given that the inhibition in calcium kinetics was comparable in all four treatments.

We next attempted to identify the transcription factors (TFs) that mediate this verapamil-specific transcriptome effect. By isolating the putative regulatory regions (20 kb around transcriptional start sites) of drug-specific genes, we identified that Myocyte-specific Enhancer Factor 2a (MEF2a) and Serum-Response Factor (SRF) are the most likely candidates (Online Figure XV). When we reduced the expression of either MEF2a or SRF using lentiviral particles, we did not observe any significant effects on cardiomyocyte contractility, either upon vehicle or verapamil treatment (Online Figure XVI). We also did not detect any contractile changes by enhancing MEF2a expression (Online Figure XVII). Thus, the transcriptome effect elicited by verapamil may involve concerted regulation by multiple transcriptional factors or post-transcriptional regulation.

iPSC-CMs recapitulate the verapamil response observed in obstructive HCM patients.

While the negative inotropic effect makes verapamil a therapeutic option to relieve the outflow tract obstruction in HCM patients, it remains difficult to predict which patient is responsive to this medication. To examine if our findings on iPSC-CMs can help address this issue, we next generated iPSCs from five HCM patients. Two responsive patients showed respectively more than 50% and 45% reduction in left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) pressure gradient at rest and during valsava maneuver after verapamil treatment, while three other HCM patients were less responsive (Online Table I). Upon verapamil treatment, responsive HCM iPSC-CMs exhibited a bigger decrease in contractile performance when compared to the non-responsive lines (Online Figure XVIII). While all HCM lines generally exhibited a reduced calcium kinetics, especially the transient amplitude (Online Figure XIX), the difference did not explain the patient-specific response in the contractility assay. However, when we examined the expressions of MYH7 and TNNI3, two proteins that were down-regulated by verapamil, a more pronounced decrease was observed in the responsive HCM lines (Online Figure XX). These findings suggest that down-regulation of myofilament genes in iPSC-CMs may explain the patient-specific response for the use of verapamil in managing obstructive HCM.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used human iPSCs to examine CCB-induced transcriptomic and functional changes in cells that are not easily accessible in the human body. Although all inhibitors act on the same principal target, the transcriptomic signatures are unique to the specific drugs. Moreover, we also identified that each line has its own adaptation to chronic exposure to the physiological dose of CCBs. Using the iPSC-CM platform, we were also able to recapitulate the patient-specific drug response to verapamil in obstructive HCM patients. This is the first study to reveal the individual- and drug-specific responses in human cardiomyocytes after CCB exposure.

The acute action of CCBs in the heart by reducing the calcium entry to achieve both negative inotropic and chronotropic effects is well-defined. These drugs are mostly used for long-term treatment in which cardiac calcium channels are at least partially inhibited for an extended period of time in patients. However, thus far cardiovascular studies lack comprehensive information on how human cardiomyocytes respond to chronic CCB exposure. Experimentally, it would be extremely difficult to isolate a patient’s cardiomyocytes for transcriptomic profiling. Despite the widespread use of animal models in cardiac research, their translational value remains questionable due to fundamental interspecies differences in cell physiology and genetic composition17,29–31. To address these issues, the iPSC-CM platform is particularly suitable for CCBs study, despite its relative immaturity32. For instance, iPSC-CMs express comparable levels of Cav1.2 protein33,34, and the activation and inactivation gating properties of calcium channel are also similar to the human ventricular cardiomyocytes30,35,36, fulfilling the prerequisite conditions for antagonism studies. In addition, the auto-rhythmicity of iPSC-CMs allows us to directly assess the negative inotropic and chronotropic effects of CCBs, which are important to establish the right experimental conditions for the study. Given our aim of examining the human transcriptome change induced by long-term CCB treatment, iPSC-CMs are the most suitable cell model for this study.

Moreover, another major advantage of this platform is that we can examine the transcriptomic signature in several iPSC-CM lines with vastly different genetic makeups37,38. By isolating the common alteration, we can gain valuable insight into the potential cardiotoxic effects of a given small molecule or biologic. This premise is demonstrated in the current study. CCBs have a relatively safe clinical profile and, consistently, we did not observe any induction of cell death-related mechanisms. However, it is interesting that all the iPSC lines showed reduction in several contractility-related genes, such as TNNI3 and MYH7, only after verapamil treatment. Motion tracking analysis also concordantly showed that verapamil exerted the biggest inhibition in contractility. Of the four inhibitors tested in the study, verapamil has been shown clinically to induce the biggest negative inotropic effect, but the cause for this unique feature remains to be explained39,40. Our study is the first to suggest that extra inhibition of contractility can be attributed to reduction in the expression of several contractile proteins. The information from transcriptome analysis collected from different patient- and disease-specific iPSC lines after treatment of any drug entity can be employed to evaluate possible side effects during the drug discovery process. This application can extend beyond the cardiovascular field, and more similar studies using other drugs and iPSC derivative cells should be conducted to examine this possibility.

When applied at the therapeutic concentration, our analysis revealed that each molecule has a distinct transcriptomic signature in cardiomyocytes, although all four drugs target the same calcium channel. Only a handful of the induced genes were shared by two or more treatments. One possible explanation is that there is a difference in the strength of inhibition at the reported serum plasma concentration. However, the motion tracking and calcium kinetics data did not support this idea as the inhibition appeared to be comparable among nifedipine, amlodipine, and diltiazem. Thus, it is more likely that the transcriptome signature was induced by individual drug-specific effects rather than direct calcium inhibition. Because a major goal in clinical practice is to prescribe the most suitable drug to patients, the ability to obtain drug-specific transcriptomic information may facilitate the decision-making. Further advances in patient genomic testing may allow clinicians to make better informed decisions on CCB drug choices by understanding the respective transcriptomic signatures of medications and how patients’ genetic makeup may influence the relevant drug-specific transcriptome alterations. Moreover, as patients on CCBs are likely prescribed other medications, understanding the transcriptome changes elicited by each drug can help identify the optimal combination to prevent toxicity and maximize drug efficacy. To that end, our study is a major first step toward establishing the foundation for future transcriptomic studies on polypharmacy.

It is known that individual patients will react to the same medication differently because of unique genetic and epigenetic influences on each person. Recent studies have identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with the variable efficacies of calcium channel inhibition in treating hypertensive patients41,42. In our study, we observed an individualized drug response upon chronic CCB exposure. All four CCBs exerted the expected acute inhibition on contractility in all tested iPSC-CM lines, suggesting that the antagonist-receptor interaction was intact. However, there were significant variations among the lines in the degree of recovery in contractile function after chronic exposure. These findings suggest that the individual response may be related to the ability to compensate for the inhibition on calcium entry, which is supported by our electrophysiological findings. In future studies, it would be interesting to identify patients who are resistant to CCBs and explore if they have SNPs in genes that are related to recovery of calcium entry/kinetics.

Moreover, our previous43 and current findings on HCM patients’ iPSC-CM lines further demonstrate the capability of iPSC-CM platform to identify patients likely to derive therapeutic benefits from CCBs. The enhanced inhibition on contractility in the CCB-responsive iPSC-CMs was related to a bigger decrease in TNNI3 and MYH7 expressions, which is in line with our transcriptomic analysis. Our study provides a glimpse into how the transcriptome information from iPSC-CMs can help identify potential markers to predict drug responsiveness, which may in turn help establish a comprehensive drug index for clinical use in the future.

In summary, we identified the unique transcriptomic signature of each CCB using human iPSC-CMs. Despite limitations in maturity and tissue complexity, iPSCs provide us with an unprecedented ability to assess the drug-induced transcriptomic changes in human cells that are otherwise inaccessible for research. This drug testing approach, combined with data from other human iPSC derivatives, will be valuable for assessing potential drug application and toxicity, significantly benefiting drug development and accelerating precision medicine initiatives in the future.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are important in managing cardiovascular diseases, such as hypertension, angina, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).

In cardiomyocytes, calcium is an essential second messenger for contraction-relaxation, cell survival signaling, and hypertrophy regulation.

The acute effect of CCB on cardiac tissue is to slow down beating rate and reduce contractile force

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Although different CCBs (nifedipine, amlodipine, diltiazem and verapamil) act on the same target, the L-type calcium channel, they have different transcriptomic effects in cardiomyocytes derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC-CMs) after chronic treatment.

CCB can lose its inhibitory effect on L-type calcium channels after chronic treatment in some iPSC-CM lines.

Verapamil exerts the highest negative inotropic effect compared to other CCBs due to down-regulation of contraction-related genes.

Although CCBs are prescribed to patients for lifelong cardiovascular disease management, the long-term impact of this pharmacological inhibition on cardiomyocytes remains to be addressed. In this study, we examined the functional and transcriptomic effect of four commonly used CCBs on different lines of iPSC-CMs. While acute treatment of CCBs exerted expected negative chronotropic and inotropic effects in all lines, we observed line-specific recovery after long-term treatment in two lines. Electrophysiological study showed that the calcium current was no longer inhibited in those lines after chronic treatment. Moreover, while all four CCBs inhibited the same channel, their transcriptome signatures were different. In particular, verapamil is the only CCB capable of down-regulating genes in contraction regulation. This down-regulation may also explain the patient-specific response for the use of verapamil in managing left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in HCM patients, as the iPSC-CMs derived from patients responsive to verapamil treatment exhibited a larger decrease in the expressions of contraction-related proteins. In summary, this study provides a glimpse into how the transcriptome information from iPSC-CMs can help identify potential markers to predict drug responsiveness for precision medicine.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the Stanford Neuroscience Microscopy Service, supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) NS069375, and the Stanford Stem Cell Institute FACS, supported by NIH S10 Shared Instrumentation Grant (1S10RR02933801). We also thank Blake Wu for editing the manuscript.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

Funding support was provided by NIH R01 HL113006, R01 HL128170, R01 HL130020, and R01 HL126527 (J.C.W) and American Heart Association 19CDA34770040 (C.K.L.).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- AP

Action potential

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- ATP1A2

ATPase Na+/K+ transporting subunit alpha 2

- ATP2A2 or SERCA2

Sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2

- CCB

Calcium channel blocker

- E-C coupling

Excitation-contraction coupling

- EHT

Engineered heart tissue

- FAT10

Ubiquitin D

- FPD

Field Potential Duration

- GO

Gene ontology

- ICaL

L-type calcium current

- iPSC

Induced pluripotent stem cell

- iPSC-CM

Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LVOT

Left ventricular outflow tract

- MYH

Myosin heavy chain

- NAD(P)H

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate)

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- SR

Sarcoplasmic Reticulum

- S100A8

S100 Calcium Binding Protein A8

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- TF

Transcription factor

- TNNI3

Cardiac troponin I

- TNNT2

Cardiac troponin T

- UBA6

Ubiquitin like modifier activating enzyme 6

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

JCW is a co-founder of Khloris Biosciences but has no competing interests, as the work presented here is completely independent.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schaper WKA, Xhonneux R, Jageneau AHM, Janssen PAJ. The cardiovascular pharmacology of Lidoflazine, a long-acting coronary vasodilator. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1966;152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melville KI, Shister HE, Huq S. Iproveratril: experimental data on coronary dilatation and antiarrhythmic action. Can Med Assoc J 1964;90:761–770. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abernethy DR, Schwartz JB. Calcium-antagonist drugs. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1447–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali MA, Rizvi S, Syed BA. Trends in the market for antihypertensive drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017;16:309–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Discovery Godfraind T. and development of calcium channel blockers. Front Pharmacol 2017;8:286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Opie LH. Pharmacological differences between calcium antagonists. Eur Heart J 1997;18 Suppl A:A71–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuo IY, Ehrlich BE. Signaling in muscle contraction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2015;7:a006023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hensley J, Billman GE, Johnson JD, Hohl CM, Altschuld RA. Effects of calcium channel antagonists on Ca2+ transients in rat and canine cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1997;29:1037–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacLennan DH, Kranias EG. Phospholamban: a crucial regulator of cardiac contractility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2003;4:566–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bers DM. Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annu Rev Physiol 2008;70:23–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tandan S, Wang Y, Wang TT, Jiang N, Hall DD, Hell JW, et al. Physical and functional interaction between calcineurin and the cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel. Circ Res 2009;105:51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen X, Nakayama H, Zhang X, Ai X, Harris DM, Tang M, et al. Calcium influx through Cav1.2 is a proximal signal for pathological cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2011;50:460–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaw RM, Colecraft HM. L-type calcium channel targeting and local signalling in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 2013;98:177–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goonasekera SA, Hammer K, Auger-Messier M, Bodi I, Chen X, Zhang H, et al. Decreased cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel activity induces hypertrophy and heart failure in mice. J Clin Invest 2012;122:280–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006;126:663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burridge PW, Matsa E, Shukla P, Lin ZC, Churko JM, Ebert AD, et al. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat Methods 2014;11:855–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu C, Oikonomopoulos A, Sayed N, Wu JC. Modeling human diseases with induced pluripotent stem cells: from 2D to 3D and beyond. Development 2018;145:dev156166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meredith PA, Elliott HL. Clinical pharmacokinetics of amlodipine. Clin Pharmacokinet 1992;22:22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raemsch KD, Sommer J. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of nifedipine. Hypertens (Dallas, Tex 1979) 1983;5:II18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma N, Zhang J, Itzhaki I, Zhang SL, Chen H, Haddad F, et al. Determining the pathogenicity of a genomic variant of uncertain significance using CRISPR/Cas9 and human-induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation 2018;138:2666–2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greene RF, Collins JM, Jenkins JF, Speyer JL, Myers CE. Plasma pharmacokinetics of adriamycin and adriamycinol: implications for the design of in vitro experiments and treatment protocols. Cancer Res 1983;43:3417–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma A, McKeithan WL, Serrano R, Kitani T, Burridge PW, del Álamo JC, et al. Use of human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes to assess drug cardiotoxicity. Nat Protoc 2018;13:3018–3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seeger T, Shrestha R, Lam CK, Chen C, McKeithan WL, Lau E, et al. A premature termination codon mutation in MYBPC3 causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy via chronic activation of nonsense-mediated decay. Circulation 2018;139:799–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tiburcy M, Hudson JE, Balfanz P, Schlick S, Meyer T, Chang Liao M-L, et al. Defined engineered human myocardium with advanced maturation for applications in heart failure modeling and repair. Circulation 2017;135:1832–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei X, Wu B, Zhao J, Zeng Z, Xuan W, Cao S, et al. Myocardial hypertrophic preconditioning attenuates cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and slows progression to heart failure through upregulation of S100A8/A9. Circulation 2015;131:1506–17; discussion 1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyd JH, Kan B, Roberts H, Wang Y, Walley KR. S100A8 and S100A9 mediate endotoxin-induced cardiomyocyte dysfunction via the receptor for advanced glycation end products. Circ Res 2008;102:1239–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pei XM, Tam BT, Sin TK, Wang FF, Yung BY, Chan LW, et al. S100A8 and S100A9 are associated with doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in the heart of diabetic mice. Front Physiol 2016;7:334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hershberger RE, Hedges DJ, Morales A. Dilated cardiomyopathy: the complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nat Rev Cardiol 2013;10:531–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seeger T, Porteus M, Wu JC. Genome editing in cardiovascular biology. Circ Res 2017;120:778–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karakikes I, Ameen M, Termglinchan V, Wu JC. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: insights into molecular, cellular, and functional phenotypes. Circ Res 2015;117:80–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen IY, Matsa E, Wu JC. Induced pluripotent stem cells: at the heart of cardiovascular precision medicine. Nat Rev Cardiol 2016;13:333–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karakikes I, Termglinchan V, Wu JC. Human-induced pluripotent stem cell models of inherited cardiomyopathies. Curr Opin Cardiol 2014;29:214–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang P, Lan F, Lee AS, Gong T, Sanchez-Freire V, Wang Y, et al. Drug screening using a library of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes reveals disease-specific patterns of cardiotoxicity. Circulation 2013;127:1677–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao C, Prodromakis T, Kolker L, Chaudhry U a R, Trantidou T, Sridhar A, et al. The effect of microgrooved culture substrates on calcium cycling of cardiac myocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Biomaterials 2013;34:2399–2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma J, Guo L, Fiene SJ, Anson BD, Thomson JA, Kamp TJ, et al. High purity human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: electrophysiological properties of action potentials and ionic currents. Am J Physiol Circ Physiol 2011;301:H2006–H2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yazawa M, Hsueh B, Jia X, Pasca AM, Bernstein JA, Hallmayer J, et al. Using induced pluripotent stem cells to investigate cardiac phenotypes in Timothy syndrome. Nature 2011;471:230–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsa E, Burridge PW, Yu K-H, Ahrens JH, Termglinchan V, Wu H, et al. Transcriptome profiling of patient-specific human iPSC-cardiomyocytes predicts individual drug safety and efficacy responses in vitro. Cell Stem Cell 2016;19:311–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burridge PW, Li YF, Matsa E, Wu H, Ong S-G, Sharma A, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes recapitulate the predilection of breast cancer patients to doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat Med 2016;22:547–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwinger RH, Böhm M, Erdmann E. Negative inotropic activity of the calcium antagonists isradipine, nifedipine, diltiazem, and verapamil in diseased human myocardium. Am J Hypertens 1991;4:185S–187S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parmley WW. Efficacy and safety of calcium channel blockers in hypertensive patients with concomitant left ventricular dysfunction. Clin Cardiol 1992;15:235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDonough CW, Gong Y, Padmanabhan S, Burkley B, Langaee TY, Melander O, et al. Pharmacogenomic association of nonsynonymous SNPs in SIGLEC12, A1BG, and the selectin region and cardiovascular outcomes. Hypertension 2013;62:48–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beitelshees AL, Navare H, Wang D, Gong Y, Wessel J, Moss JI, et al. CACNA1C gene polymorphisms, cardiovascular disease outcomes, and treatment response. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2009;2:362–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lan F, Lee AS, Liang P, Sanchez-Freire V, Nguyen PK, Wang L, et al. Abnormal calcium handling properties underlie familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pathology in patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2013;12:101–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.