Abstract

Electron deficient “holes” migrate over long distances through the π-system in free DNA. Hole transfer efficiency (HTE) is strongly dependent on sequence and p-stacking. However, there is no consensus regarding the effects of nucleosome core particles (NCPs) on hole migration. We quantitatively determined HTE in free DNA and NCPs by independently generating holes at specific positions in DNA. The relative HTE varied widely with respect to position within the NCP and proximity to tyrosine, which suppresses hole transfer. These data indicate that hole transfer in chromatin will be affected by the DNA sequence and its position with respect to histone proteins within NCPs.

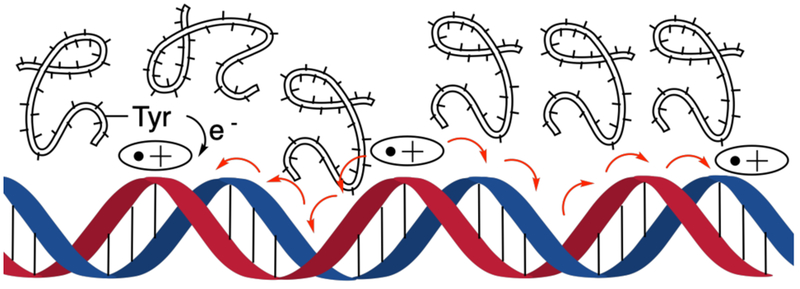

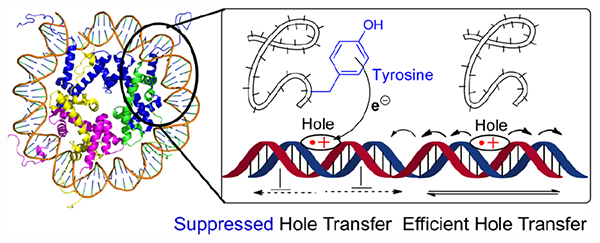

Graphical Abstract

One electron oxidation of DNA produces “holes” that can migrate rapidly over long distances in a sequence dependent manner.1–5 The electron deficient sites preferably localize at dG, the most readily oxidized native nucleotide.6,7 Runs of as few as two consecutive dG’s are often used as thermodynamically sinks to trap holes that are transformed into alkali-labile lesions.8–11 Hole transfer proceeds through the π-system, and is useful for detecting changes in DNA structure, particularly those that result in alterations in π-stacking. DNA hole transfer also plays a role in modulating the activity of redox active iron-sulfur cluster containing enzymes, such as polymerases, transcription factors, and repair enzymes that act on nucleic acids.1,12–15 A limited number of studies on hole transfer within nucleosome core particles (NCPs) have been carried out.16–19 Conclusions regarding hole transfer efficiency (HTE) in NCPs compared to that in free DNA varied, and the effects of the NCP on hole transfer remain uncertain. We wish to report our quantitative characterization of NCP effects on localized DNA hole transfer.

NCPs, the monomeric components of chromatin, are nucleoprotein complexes in which nuclear DNA is condensed. Duplex DNA (~145 base pairs) wraps approximately 1.6–1.7 turns around an octameric core containing two copies of four highly positively charged histone proteins (H2A, H2B, H3, H4).20–22 DNA kinks and stretching within NCPs could affect hole transfer by altering p-stacking. In addition, hole transfer can be suppressed by histone tyrosine residues that rapidly reduce dG•+.23,24 Consequently, HTE within a NCP may depend on the location of the DNA over which hole migration occurs with respect to the protein structure, in addition to the DNA sequence.

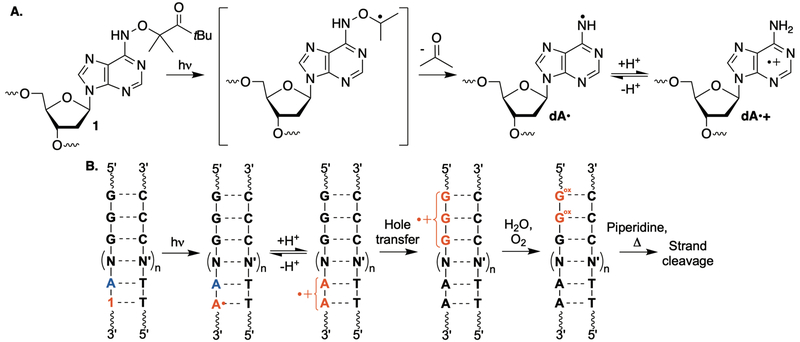

We introduced holes at defined positions in DNA using modified nucleotide 1, which generates the 2’-deoxyadenosin-N6-yl radical (dA•) via tandem Norrish Type I photo cleavage, and acetone release by β-fragmentation (Scheme1A).25 When flanked by dA, the pKa of dA•+ is increased to ~7, such that the radical-cation is produced from dA• and hole migration ensues (Scheme 1B).26–28 This method enables irreversible hole injection, which simplifies quantitative analyses. Furthermore, following hole migration, the initially formed dA•+ is transformed into dA, which also facilitates quantifying hole transfer efficiency (HTE). dA•+ generation within judiciously chosen sequences (e.g. 5’-d(TT1A)), enables estimation of the amounts of hole injected into DNA by detecting its transformation into dA via restriction enzyme cleavage (e.g. MseI). The amount of dA formed is the upper limit for dA•+ formation from 1. Accounting for the amounts of holes introduced eliminates conversion of 1 as a variable for determining HTE.

Scheme 1.

Site selective generation of dA•+ and hole transfer detection.

| (Eqn. 1) |

The 145 bp DNA sequences used in these experiments were based upon the “601” strong-positioning sequence.29 The sequences also contain a dG rich region to serve as a sink for holes.8–11 The trapped holes are transformed into alkali-la-bile lesions that are detected by gel electrophoresis. The amount of hole migration in the photolyzed samples was determined by measuring the yield of alkali-labile lesions within the dG5 sequence(s), and was corrected for background cleavage in unphotolyzed samples.30 HTE (Eqn. 1) was defined as the fraction of dA•+ that results in formation of an alkali-labile lesion within the dG5 sequence(s).

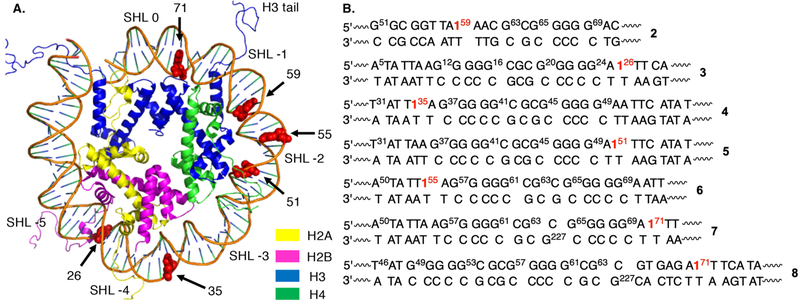

dA•+ was generated at position 59 of the 601 DNA(2, Fig. 1B) within a run of 4 dA’s that is approximately 1.5 helical turns (superhelical location (SHL) −1.5) from the dyad axis (Fig. 1A). (The SHL denotes the translational position within the NCP.) Hole hopping was expected to occur from the dA polaron to dG63 and again two nucleotides further to the dG5 sequence.3,5 The HTE in free DNA (HTEDNA = 5.5 ± 0.2) was more than 5-times greater than in the NCP (HTENCP = 1.1 ±0.2) (Fig. S6). This difference is qualitatively consistent with, but greater than the observation made by Shafirovich who examined hole transfer in a region approximately one helical turn further from the dyad axis (SHL −2.5 − 1.0).19,31

Figure 1.

Nucleosome core particles containing 1 at individual sites. A. Single gyre showing positions at which 1 is introduced in 2–8 (pdb: 1kx5). B. Sequences substituted for corresponding region of 601 DNA.

Subsequent experiments were designed to explore the effect of translational location in the NCP on the relative hole transfer efficiency (HTERel = HTEDNA / HTENCP). A consensus DNA sequence (“cassette”) containing 1 and two closely spaced dG5 runs was substituted for equal length regions of the 601 DNA to minimize sequence variability and to increase hole capture (Fig. 1B). Generating dA•+ at position 26 (3) resulted in no difference in HTE in free DNA and the NCP, consistent with the observation by Barton for oxidation of d(GG) at a comparable position (Table 1, Fig. S7).16 The lack of an effect could be attributed to NCP dynamics that compete with hole trapping by H2O and/or deprotonation. Rapid DNA unwrapping from the histone core in this region has been used to rationalize the lack of a difference in hydroxyl radical and glycosylase reactivity between free DNA and NCPs.32,33 In contrast, when the cassette was positioned 25 nts further from the DNA terminus where unwrapping was expected to be insignificant, HTE was slightly higher in the NCP than in free DNA(Table 1, Fig. S8, 9). Preferential hole transfer in the NCP was observed whether dA•+ was generated on the 5’– (position 35, 4) or 3’– (position 51, 5) side of the dG rich sequence, consistent with the bidirectional flow of holes through DNA.34

Table 1.

Hole transfer efficiency as a function of hole injection position.a

| Substrate | Hole Inj. Position |

HTEDNA(%)b | HTENCP(%)b | HTERe1c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 26 | 7.0 ± 0.2 | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| 4 | 35 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 7.4 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| 5 | 51 | 9.1 ± 0.9 | 14.1 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| 6 | 55 | 6.5 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.5 |

| 6 (D2O) | 55 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| 7 | 71 | 9.6 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.3 |

| 7 (D2O) | 71 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

See Supporting Information for sample autoradiograms.

Values are the ave. ± std. dev. of 2 experiments, each consisting of 3 replicates.

HTERel = HTEDNA / HTENCP.

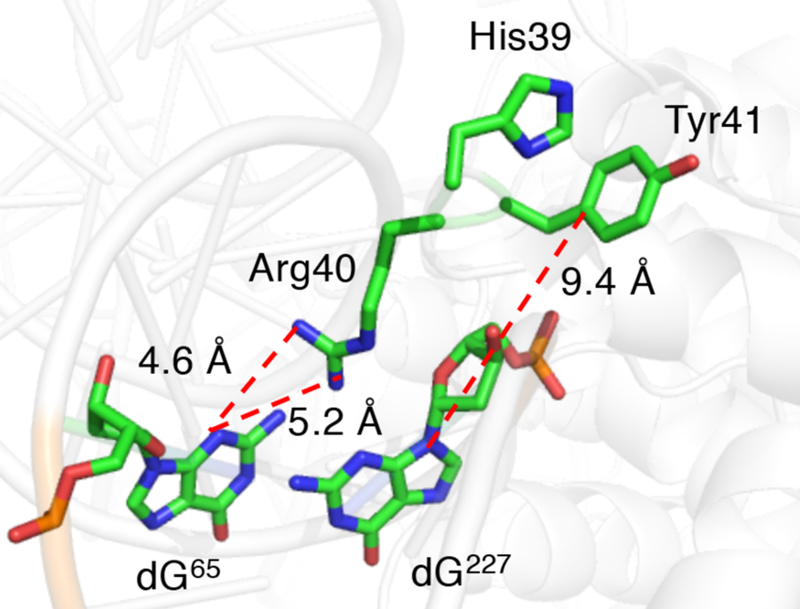

Positioning the cassette in the region where dA•+ was initially injected (position 59, 2) again gave rise to a significant decrease in HTE within the NCP (6, 7, Table 1, Fig. S10, 11). The magnitude of HTERel also did not depend on which side of the dG rich region the hole was injected. X-ray crystal structural data (Fig. 1A, 2) reveal that the N-terminal histone H3 tail protrudes through the octameric core in this region and tyrosine 41 (Tyr41), a possible reducing agent for the guanine radical(s) is approximately 9.4 Å from dG227.21 Rotations within the flexible tail could bring Tyr41 even closer to the DNA, accounting for the significant decrease in HTENCP. Model studies showed that the rate constant for dG•+ reduction by tyrosine is >106 greater than that for trapping by H2O (~6 × 104 s−1, pH 7).24,35,36 This suggests that dG•+ reduction by tyrosine within a NCP can compete with deprotonation and hole transfer.36,37

Figure 2.

Potential histone H3-DNA interactions resulting in suppression of hole transfer in NCPs (pdb: 3lz0).

Hole reduction in DNA by Tyr41 was initially probed by examining the effect of deuterated buffer on HTE (Fig. S12, 13). We anticipated that reduction by Tyr41 would occur via proton coupled electron transfer (PCET) and would therefore be susceptible to a deuterium kinetic isotope effect (KIE).38,39 The deuterated buffer could influence multiple steps leading to alkali-labile product(s). Specifically, the observed KIE could be a manifestation of a decreased rate constant for both dA•+ formation from dA• and deprotonation of the dG•+ at the ultimate site of alkali-labile lesion formation in deuterated buffer.40–42 The rate constants for these steps should decrease within free DNA or a NCP, albeit possibly by different amounts, when deuterated buffer is employed. Importantly, the rate constant for reduction by Tyr41 will also decrease in deuterated buffer, reducing its ability to suppress hole transfer and ensuing alkali-labile lesion formation. Consequently, HTEDNA would decrease more than HTENCP in deuterated buffer, and the latter could even increase in an absolute sense. Indeed, HTEDNA (Table 1) decreased in deuterated buffer when the hole was injected at position 55 (6) and position 71 (7). In contrast, HTENCP in creased at these same positions in deuterated buffer. Overall, the HTERel decreased significantly in deuterated buffer in 6 and 7, supporting the proposal that Tyr41 competes with hole transfer in this region.

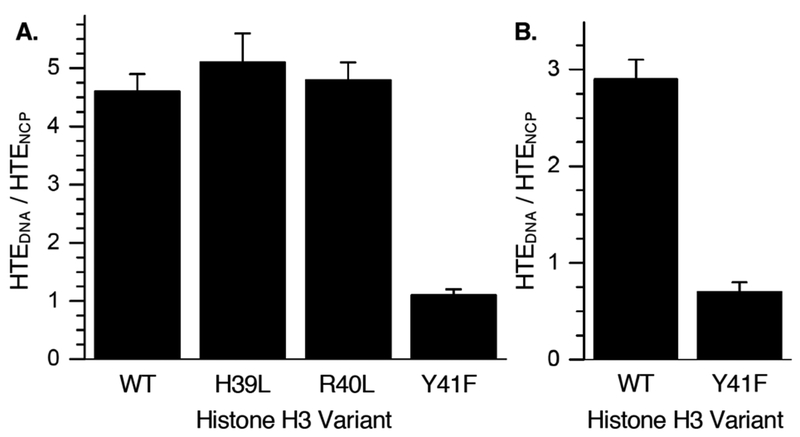

Additional evidence that histone H3 suppresses hole transfer was gleaned by comparing the HTE (using 7) in an NCP containing wild type (WT) histone H3 to a series of NCPs comprised of histone H3 variants. Specifically, these experiments probed whether amino acids in the flexible N-terminal histone H3 tail suppress hole transfer (Fig. 2). In addition to tyrosine (Tyr41), histidine (His39) and arginine (Arg40) are also proximal to the DNA where hole transfer occurs in 7. Histidines play an important role in PCET within proteins.43 Arginines have been postulated to suppress hole transfer by interacting with dG, and Arg40 can form hydrogen bonds with dG65.44 The relative hole transfer efficiencies in NCPs in which either His39 (H3–H39L) or Arg40 (H3–R40L) was mutated were within experimental error of that observed when wild type histone H3 was used (Fig. 3A), indicating that these amino acids do not suppress hole transfer in 7 (Fig. S15,16). However, replacing Tyr41 with phenyl alanine (H3–Y41F) eliminated any difference in HTE between the free DNA and NCP containing this variant (Fig. S14).

Figure 3.

The effect of histone H3 variants on hole transfer efficiency in NCPs containing (A.) 7 or (B.) 8.

These data show that the observed HTE in NCPs is effectively suppressed by a tyrosine that is suitably positioned with respect to one or more dG5 thermodynamic hole sinks. We propose that hole reduction by tyrosine competes with water trapping and/or deprotonation, resulting in decreased alkali-labile lesion yields. Using 8 (Fig. 1B) we examined the ability of histone H3-Tyr41 to suppress hole transfer when it is proximal to isolated dG227 through which a hole hops en route to a dG5 sequence that is 2 base pairs further away. The HTE in free DNA was almost 3-times greater than in the NCP containing wild type histone (Fig. 3B, Fig. S17, 18). In contrast, the HTE was actually greater in the NCP when H3–Y41F was used to assemble the core particle. Importantly, this suggests that the reduction by tyrosine can compete with hole hopping to suppress electron transfer (Scheme 2).5 DNA unwrapping is extremely slow in this region of the NCP, and is not a viable explanation for the these observations.32

Scheme 2.

Hole transfer suppression by tyrosine.

General conclusions from previous investigations concerning the effects of NCPs on DNA hole transfer efficiency varied, and included that there was no effect, as well as that charge transfer was less efficient and more efficient within nucleosomes.16–19 Our experiments reveal that the situation is more nuanced. Independent generation of dA•+ from 1 shows that HTE will not only be affected by DNA sequence, which is well accepted, but also by the positioning of the DNA sequence with respect to the histone proteins that make up the nucleosomal core. For instance, unwrapping reduces the differences between free DNA and the NCP environment. Furthermore, a tyrosine residue that is proximal to the hole transfer path can suppress DNA hole migration. However, we did not observe DNA-protein cross-links (Fig. S19).23,45

Although these experiments were carried out using histones from Xenopus laevis, histone H3-Tyr41 is conserved in a number of organisms, including humans (Fig. S30). Human chromatin is composed of approximately 15 million unique nucleosomes. Statistically, it is likely that DNA sequences through which hole transfer is efficient will be proximal to a tyrosine residue in some nucleosomes. Our results suggest that localized hole transfer will be suppressed in these nucleosomes. Such interactions add a layer of complexity to the role of hole transfer in cells that could affect biologically important issues such as modulating the activity of enzymes that interact with DNA.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful for generous financial support from the National Institute of General Medical Science (GM-054996). LZ thanks Johns Hopkins University for the Glen E. Meyer ‘39 Fellowship.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Experimental details. ESI-MS of oligonucleotides containing 1 and representative autoradiograms. Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

REFERENCES

- (1).Zwang TJ; Tse ECM; Barton JK Sensing DNA through DNA Charge Transport. ACS Chem. Biol 2018, 13, 1799–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Slinker JD; Muren NB; Renfrew SE; Barton JK DNA Charge Transport over 34 Nm. Nat. Chem 2011, 3, 228–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Schuster GB Long-Range Charge Transport in DNA: Transient Structural Distortions Control the Distance Dependence. Acc. Chem. Res 2000, 33, 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Giese B Long-Distance Charge Transport in DNA: The Hopping Mechanism. Acc. Chem. Res 2000, 33, 631–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Lewis FD; Liu J; Zuo X; Hayes RT; Wasielewski MR Dynamics and Energetics of Single-Step Hole Transport in DNA Hairpins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 4850–4861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Steenken S; Jovanovic SV How Easily Oxidizable Is DNA? One-Electron Reduction Potentials of Adenosine and Guanosine Radicals in Aqueous Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119, 617–618. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Thapa B; Schlegel HB Calculations of Pka’s and Redox Potentials of Nucleobases with Explicit Waters and Polarizable Continuum Solvation. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 5134–5144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hall DB; Holmlin RE; Barton JK Oxidative DNA Damage through Long-Range Electron Transfer. Nature 1996, 382, 731–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Saito I; Nakanura T; Nakatani K; Yoshioka Y; Yamaguchi K; Sugiyama H Mapping of the Hot Spots for DNA Damage by One-Electron Oxidation: Efficacy of GG Doublets and GGG Triplets as a Trap in Long-Range Hole Migration. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 12686–12687. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Meggers E; Michel-Beyerle ME; Giese B Sequence Dependent Long Range Hole Transport in DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 12950–12955. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Sugiyama H; Saito I Theoretical Studies of GG-Specific Photocleavage of DNA Via Electron Transfer: Significant Lowering of Ionization Potential and 5’-Localization of Homo of Stacked GG Bases in B-Form DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 7063–7068. [Google Scholar]

- (12).McDonnell KJ; Chemler JA; Bartels PL; O’Brien E; Marvin ML; Ortega J; Stern RH; Raskin L; Li G-M; Sherman DH; Barton JK; Gruber SB A Human Mutyh Variant Linking Colonic Polyposis to Redox Degradation of the [4Fe4S]2+ Cluster. Nature Chem 2018, 10, 873–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).O’Brien E; Holt ME; Thompson MK; Salay LE; Ehlinger AC; Chazin WJ; Barton JK The [4Fe4S] Cluster of Human DNA Primase Functions as a Redox Switch Using DNA Charge Transport Science 2017, 355, 813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Bartels PL; Stodola JL; Burgers PMJ; Barton JK A Redox Role for the [4Fe4S] Cluster of Yeast DNA Polymerase Δ. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 18339–18348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Grodick MA; Muren NB; Barton JK DNA Charge Transport within the Cell. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 962–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Núnez ME; Noyes KT; Barton JK Oxidative Charge Transport through DNA in Nucleosome Core Particles. Chem. & Biol. 2002, 9, 403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Bjorklund CC; Davis WB Attenuation of DNA Charge Transport by Compaction into a Nucleosome Core Particle. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 1836–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Davis WB; Bjorklund CC; Deline M Probing the Effects of DNA-Protein Interactions on DNA Hole Transport: The N-Terminal Histone Tails Modulate the Distribution of Oxidative Damage and Chemical Lesions in the Nucleosome Core Particle. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 3129–3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Liu Y; Liu Z; Geacintov NE; Shafirovich V Proton-Coupled Hole Hopping in Nucleosomal and Free DNA Initiated by Site-Specific Hole Injection. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2012, 14, 7400–7410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Luger K; Mader AW; Richmond RK; Sargent DF; Richmond TJ Crystal Structure of the Nucleosome Core Particle at 2.8 Å Resolution. Nature 1997, 389, 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Vasudevan D; Chua EYD; Davey CA Crystal Structures of Nucleosome Core Particles Containing the ‘601’ Strong Positioning Sequence. J. Mol. Biol 2010, 403, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Davey G; Wu B; Dong Y; Surana U; Davey CA DNA Stretching in the Nucleosome Facilitates Alkylation by an Intercalating Antitumor Agent. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 2081–2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Lee M; Urata SM; Aguilera JA; Perry CC; Milligan JR Modeling the Influence of Histone Proteins on the Sensitivity of DNA to Ionizing Radiation. Radiat. Res 2012, 177, 152–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Tsoi M; Do TT; Tang VJ; Aguilera JA; Milligan JR Reduction of Electron Deficient Guanine Radical Species in Plasmid DNA by Tyrosine Derivatives. Org. Biomol. Chem 2010, 8, 2553–2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Zheng L; Griesser M; Pratt DA; Greenberg MM Aminyl Radical Generation Via Tandem Norrish Type I Photocleavage, B-Fragmentation: Independent Generation and Reactivity of the 2’-Deoxyadenosin- N6-yl Radical. J. Org. Chem 2017, 82, 3571–3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Adhikary A; Kumar A; Khanduri D; Sevilla MD Effect of Base Stacking on the Acid-Base Properties of the Adenine Cation Radical [A•+] in Solution: Esr and Dft Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 10282–10292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Zheng L; Greenberg MM DNA Damage Emanating from a Neutral Purine Radical Reveals the Sequence Dependent Convergence of the Direct and Indirect Effects of g-Radiolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 17751–17754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Sun H; Zheng L; Greenberg MM Independent Generation of Reactive Intermediates in DNA Leads to an Alternative Mechanism for Strand Damage Induced by Hole Transfer in Poly•(dA-T) Sequences. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 11308–11316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lowary PT; Widom J New DNA Sequence Rules for High Affinity Binding to Histone Octamer and Sequence-Directed Nucleosome Positioning. J. Mol. Biol 1998, 276, 19–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).See Supporting Information.

- (31).These researchers reported that hole transfer was reduced 1.2–1.5 fold in NCPs but the effect may have been underestimated. Examination of their data (Fig. 3, ref. 19) suggests that a greater reduction was observed in the NCP if one includes damage at a dG5 sequence 4 nucleotides further in the 3’-direction.

- (32).Tims HS; Gurunathan K; Levitus M; Widom J Dynamics of Nucleosome Invasion by DNA Binding Proteins. J. Mol. Biol 2011, 411, 430–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Bilotti K; Tarantino ME; Delaney S Human Oxoguanine Glycosylase 1 Removes Solution Accessible 8-Oxo-7,8-Dihydroguanine Lesions from Globally Substituted Nucleosomes except in the Dyad Region. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 1436–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).O’Neill MA; Barton JK Effects of Strand and Directional Asymmetry on Base-Base Coupling and Charge Transfer in Double-Helical DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 16543–16550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Giese B; Spichty M Long Distance Charge Transport through DNA: Quantification and Extension of the Hopping Model. ChemPhysChem 2000, 1, 195–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Rokhlenko Y; Cadet J; Geacintov NE; Shafirovich V Mechanistic Aspects of Hydration of Guanine Radical Cations in DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 5956–5962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Lewis FD; Young RM; Wasielewski MR Tracking Photoinduced Charge Separation in DNA: From Start to Finish. Acc. Chem. Res 2018, 51, 1746–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Weinberg DR; Gagliardi CJ; Hull JF; Murphy CF; Kent CA; Westlake BC; Paul A; Ess DH; McCafferty DG; Meyer TJ Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 4016–4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Glover SD; Jorge C; Liang L; Valentine KG; Hammarstroem L; Tommos C Photochemical Tyrosine Oxidation in the Structurally Well-Defined A3y Protein: Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer and a Long-Lived Tyrosine Radical. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 14039–14051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Weatherly SC; Yang IV; Thorp HH Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in Duplex DNA: Driving Force Dependence and Isotope Effects on Electrocatalytic Oxidation of Guanine. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 1236–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Giese B; Wessely S The Significance of Proton Migration During Hole Hopping through DNA. Chem. Commun 2001, 2108–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Shafirovich V; Dourandin A; Luneva NP; Geacintov NE The Kinetic Deuterium Isotope Effect as a Probe of a Proton Coupled Electron Transfer Mechanism in the Oxidation of Guanine by 2-Aminopurine Radicals. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 137–139. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Pagba CV; McCaslin TG; Chi S-H; Perry JW; Barry BA Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer and a Tyrosine-Histidine Pair in a Photosystem II-Inspired B-Hairpin Maquette: Kinetics on the Picosecond Time Scale. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 1259–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Nakatani K; Dohno C; Ogawa A; Saito I Suppression of DNA-Mediated Charge Transport by Bamhi Binding. Chem. Biol 2002, 9, 361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Bjorklund CC; Davis WB Stable DNA-Protein Cross-Links Are Products of DNA Charge Transport in a Nucleosome Core Particle. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 10745–10755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.