Abstract

Purposes

To establish a scoring model for the risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) following pancreatoduodenectomy (PD).

Methods

PD Patients from 7 institutions in 2 independent sets: developmental (n = 457) and validation cohort (n = 152) were retrospectively enrolled and analyzed. Pancreatic Fibrosis (PF) and Pancreatic Steatosis (PS) were assessed by pathological examination of the pancreatic stump.

Results

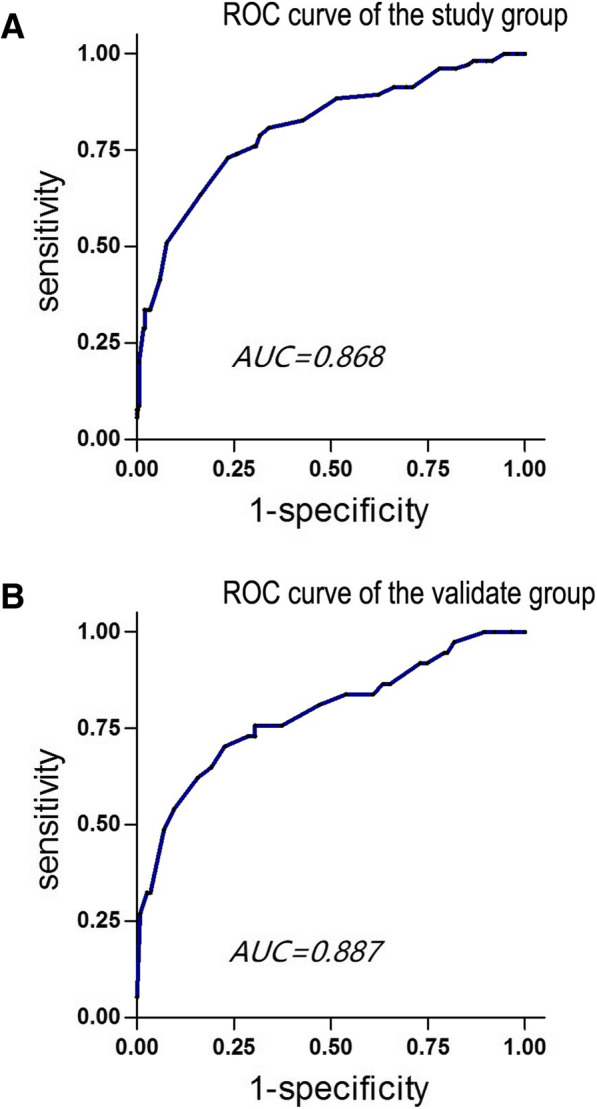

Stepwise univariate and multivariate analysis indicated that pancreatic duct diameter ≤ 3 mm, increased PS and decreased PF were independent risk factors for POPF and Clinically Relevant Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula (CR-POPF). Based on the relative weight and odds ratio of each factor in the POPF, a simplified scoring model was developed. And patients were stratified into high-risk group (22~28 points), medium-risk group (15~21 points) and low-risk group (8~14 points). The receiver operating characteristic curve demonstrated that the Area under the curve for the predictive model was 0.868 and 0.887 in the model design group and the external validation group.

Conclusions

This study establishes a simplified scoring model based on accurately and quantitatively measuring the PS, PF and pancreatic duct diameter. The scoring model accurately predicted the risk of POPF.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12893-019-0534-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pancreatic fibrosis, Pancreatic steatosis, Postoperative pancreatic fistula, Scoring model

Introduction

Pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) is the optimal treatment for most malignant and benign neoplasms of the pancreatic head and periampullary region. Serious postoperative complications raise concerns for surgeons [1], along with surgical technical difficulty. Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is one of the most common complications [2]. POPF not only may result in massive intra-abdominal hemorrhaging and severe intraperitoneal infection [3, 4], but is also the most important determinant of death after PD [5]. Surgeons and researchers have attempted to develop various strategies to decrease the incidence of pancreatic leakage after PD such as anastomosis of the pancreas and intestine or placing a tube to support the pancreatic duct [6–8]. Despite many such attempts, the incidence of POPF following PD is still in the 10–28% range [9]. It has been well known that some chronic morbidities, such as alcohol and smoking, contribute to diverse conditions in each patient, especially in regards to the texture of the pancreas [10, 11]. Questions have been raised as to whether pancreatic texture is a potential factor causing high incidence of POPF and if individualized management based on pancreatic texture might change the status quo.

It is believed that the softness or hardness of the pancreas is related to POPF. A soft pancreas makes performing anastomosis of the pancreas and intestine more difficult and makes it easier for the suture line to tear pancreatic tissue. Pancreatic texture can also affect pancreatic exocrine function [12]. The robustness of pancreaticojejunostomy and pancreatic exocrine function both contribute to the occurrence of pancreatic fistula after surgery [13]. However, current research is controversial as to whether a hard pancreas can decrease, or a soft pancreas increase, the incidence of POPF [14–16]. The controversy is not surprising because there are no consensus criteria for quantitatively evaluating pancreatic texture, and when assessed subjectively by each operator, results may differ in perceptions of softness and hardness. Moreover, the cut-off for defining a soft or hard pancreas is also unclear. Using preoperative imaging modalities (CT or MRI) to assess the texture of the pancreas has been attempted. However, imaging modalities only indirectly reflected the texture of the pancreas and can be impacted by many factors. For example, artifacts in MRI can significantly interfere with the evaluation of the fat content of the pancreas.

The softness or hardness of pancreatic texture is determined by the composition of the pancreatic parenchyma which is influenced by the balance of fibrous and fatty tissue [17, 18]. Therefore, pathological analysis of the pancreatic microstructure is the most accurate method to assess pancreatic texture. The aim of this study was to investigate the correlation between the microscopic pathological structure of the pancreas, including level of pancreatic fibrosis (PF) and pancreatic steatosis (PS), and the incidence of POPF after PD in a multicenter retrospective study.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology and was carried out in accordance with the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent for the use of the specimen was obtained from all participants.

Retrospective study population and patient selection

Seven pancreatic surgery centers contributed to the study (see the institutional affiliations of the authors). The patients’ data from January 2014 to December 2017 were collected and analyzed retrospectively. The eligibility criteria included age greater than 18 years old; died within 1 week. A total of 609 consecutive patients were included in the study for risk factor analysis and the development of a risk score. The risk score was calculated retrospectively after the review of patient records. The patients were represented in the study by code numbers and their personal data were concealed.

Surgical technique and perioperative management

Each patient was placed in the supine position. The Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy.

(OPD) usually required a long midline incision or straight incision through right rectus abdominis. The Laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy (LPD) required drilling five small holes in the patient’s abdomen. The supporting stent of the pancreatic duct was placed in some of the patients. Closed rubber drainage tubes were placed near the pancreatic anastomosis and choledochojejunostomy sites. Pancreatic texture and pancreatic duct diameter were assessed by the surgeons.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics (Paclitaxel sulbactam sodium) were intravenously administered to all patients for 3 days after surgery. If there was a clear sign of infection, the period of antibiotic treatment was prolonged. All patients received an H2 blocker every 12 h intravenously during the period after surgery when there was no oral intake. After 5d of postoperative octreotide treatment by a 24 h intravenous pump, octreotide dosing was switched to subcutaneous administration (100 mg every 6 h for 7d). The amount of fluid drainage from the peripancreatic site was measured daily and the amylase levels of serum and fluid drainage were measured on postoperative day 1, 3, 5, 7 and 10. On postoperative day 7 an abdominal CT scan was performed and the peripancreatic drainage tube was removed, provided there was no evidence of leakage or fluid collection.

Hematoxylin and eosin analysis of paraffin embedded sections

The paraffin embedded sections from the pancreatic stump specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and reviewed by two experienced pathologists who were blinded to the surgical outcome. Based on the criteria of Klopper and Maillet [19], pancreatic fibrosis and pancreatic steatosis was evaluated. The degree of intralobular and interlobular fibrosis was separately scored from 0 to 6 and the total score (0–12) was calculated. According to the total score, fibrosis was classified into normal (Grade 0, score 0–3), mild fibrosis (Grade 1, score 4–6), moderate fibrosis (Grade 2, score 7–9) and severe fibrosis (Grade 3, score 10–12). The degree of pancreatic fat infiltration was assessed based on the percentage of the interlobular fat to total interlobular space and the percentage of the intralobular fat to total intralobular space. The sum of the intralobular and interlobular fat percentages was calculated. Pancreatic steatosis was graded into 4 categories: normal (Grade 0: 0–10%), mild lipomatosis (Grade 1: 11–40%), moderate lipomatosis (Grade 2: 41–70%), and severe lipomatosis (Grade 3: 71–100%).

Definition of pancreatic fistula

The International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) definition on POPF was used in our study [20].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Univariable analysis was performed on the various parameters of the POPF and non-POPF, CR-POPF and non-CR-POPF groups. The variables were then selected into multivariable logistic regression models, with forward stepwise selection procedures. Statistically significant differences were defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic and Clinicopathologic characteristics of cohort

Patient demographics and perioperative characteristics are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. During the study period, a total of 609 patient underwent PD at the 7 participating centers. The patients were comprised of 383 men (62.9%) and 226 women (37.1%), with a median age of 54.6 years (range: 18–82 years). The median BMI was 22.0 kg/m2 (range: 15.1–34.0 kg/m2). Most patients had ASA scores of II (74.1%) or III (17.2%). The mean preoperative TBIL was 138.2 μmol/L (range: 3.7–570.2 μmol/L) and the mean preoperative DBIL was 72.3 μmol/L (range: 0.5–278.4 μmol/L). The mean preoperative ALT was 147.0 U/L (range: 1.2–1099.0 U/L); the mean preoperative AST was 113.2 U/L (range: 9.0–1628.0 U/L). The mean preoperative CT Hu value was 39.6 (range: 16.3~65.7). Prior abdominal surgery had been performed in 23.6% of the patients. Preoperative jaundice and abdominal pain were the most common clinical symptoms. The preoperative diagnoses of mass location were pancreatic head (66.3%), duodenum (7.2%), biliary duct (17.6%), and ampulla (9.0%).

Intraoperative details are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed in 79 patients (13.0%) and OPD in 530 patients (87.0%). The median operative time was 398.8 min (SD = 120.1 min). The methods of pancreatic remnant anastomosis included PJ (85.6%) and PG (14.4%). Stenting of the pancreatic duct was required in 554 cases (92.0%). The median estimated intraoperative blood loss was 489.6 mL (SD = 345.7 mL). Intraoperative blood transfusions were needed in 129 patients (21.2%); the median estimated volume of intraoperative blood transfusion was 173.0 mL (SD = 231.5 mL).

Postoperative details are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. According to the ISGPF, 73 patients (12.0%) had a grade A POPF; these patients were treated conservatively and fed orally without additional intervention. Grade B POPF occurred in 41 patients (6.7%) and grade C POPF in 27 patients (4.4%).

Pathological outcomes are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. Lesions were caused by chronic inflammation in 82 cases (13.5%), cystic neoplasia of the pancreas in 82 cases (13.5%), ampullary carcinoma in 55 cases (9.0%), duodenal lesions in 43 cases (7.1%), cholangiocarcinoma in 107 cases (17.6%), and pancreatic carcinoma in 245 cases (40.2%). The grade of pancreatic fibrosis of the pancreatic stump was normal in 168 cases (27.6%), mild in 181 cases (29.7%), moderate in 204 cases (33.5%), and severe in 56 cases (9.2%). The grade of pancreatic steatosis of the pancreatic stump was normal in 292 cases (47.9%), mild in 205 cases (33.7%), moderate in 95 cases (15.6%), and severe in 17 cases (2.8%).

Univariate analysis and correlation of variables with POPF

A total of 640 patient was identified, with 31 being excluded from analysis because of missing data. Postoperative pancreatic fistula occurred in 141 of the 609 patients (23.2%). Univariate analyses of the variables and their association with POPF are shown in Table 1. In total, the 10 variables (BMI, AST, CT Hu value, pancreatic texture, pancreatic duct diameter, surgery approach, operating time, histopathology, PF and PS) were significantly different between the no-POPF group and POPF group. Univariate analyses of the variables and their association with CR-POPF are shown in Table 3. In total, the 4 variables (pancreatic texture, pancreatic duct diameter, PF and PS) were significantly different between the no-CR-POPF group and CR-POPF group.

Table 1.

Univariate Analysis and Relationship of Variables With POPF

| Variables | No | POPF | P | CR-POPF | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no | yes | no | yes | ||||

| Sex: Male / Female | 383/226 | 285/183 | 98/43 | 0.064 | 340/201 | 43/25 | 0.173 |

| Age: ≤55/> 55 | 300/309 | 227/241 | 73/68 | 0.281 | 265/276 | 35/33 | 0.699 |

| BMI: ≤23/> 23 | 327/282 | 268/200 | 59/82 | 0.001 | 290/251 | 37/31 | 0.900 |

| Diabetes: No/Yes | 551/58 | 423/45 | 128/13 | 0.889 | 489/52 | 62/6 | 0.546 |

| Abdominal surgery history: No/Yes | 465/144 | 352/166 | 133/28 | 0.227 | 403/128 | 52/16 | 0.917 |

| RBC: normal / abnormal | 392/217 | 305/163 | 87/54 | 0.451 | 348/193 | 44/24 | 0.951 |

| PCT: ≤0.5/> 0.5 ng/mL | 374/235 | 288/180 | 86/55 | 0.907 | 231/210 | 43/25 | 0.095 |

| ALT: ≤40/> 40 U/L | 204/405 | 166/302 | 38/103 | 0.060 | 181/360 | 23/45 | 0.952 |

| AST: ≤40 / > 40 U/L | 229/380 | 189/279 | 40/101 | 0.009 | 203/338 | 26/42 | 0.909 |

| Platelet: normal / abnormal | 466/143 | 362/106 | 104/37 | 0.378 | 408/127 | 52/16 | 0.969 |

| Total Bilirubin: ≤171 / > 171 μmol/L | 424/185 | 334/134 | 90/51 | 0.088 | 377/164 | 47/21 | 0.923 |

| Direct Bilirubin: ≤110 / > 110 μmol/L | 350/259 | 272/196 | 78/63 | 0.555 | 311/230 | 39/29 | 0.913 |

| CT Hu value: ≤40Hu / >40Hu | 423/186 | 336/132 | 87/54 | 0.023 | 371/110 | 52/16 | 0.903 |

| Surgery approach: OPD / LPD | 530/79 | 397/71 | 133/8 | 0.003 | 467/74 | 63/5 | 0.143 |

| Pancreatic texture (evaluation by surgeon) | |||||||

| soft | 318 | 211 | 107 | < 0.001 | 276 | 42 | < 0.001 |

| middle | 205 | 174 | 31 | 179 | 26 | ||

| hard | 86 | 83 | 3 | 86 | 0 | ||

| Operating time: ≤240 min / > 240 min | 273/336 | 222/246 | 51/90 | 0.018 | 241/300 | 32/36 | 0.695 |

| Pancreatic duct diameter: ≤3 / > 3 mm | 312/297 | 206/262 | 106/35 | < 0.001 | 298/243 | 14/54 | < 0.001 |

| Intraoperative bleeding: ≤400 / > 400 mL | 387/222 | 298/170 | 73/50 | 0.905 | 244/197 | 43/25 | 0.221 |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion: ≤400 / > 400 mL | 563/46 | 432/36 | 131/10 | 0.813 | 500/41 | 63/5 | 0.859 |

| Histopathology | |||||||

| Chronic inflammation | 77 | 63 | 14 | < 0.001 | 68 | 9 | 0.074 |

| Cystic neoplasia of the pancreas | 82 | 63 | 19 | 73 | 9 | ||

| Ampullary carcinoma | 55 | 42 | 13 | 49 | 6 | ||

| Duodenal lesions | 43 | 22 | 21 | 38 | 5 | ||

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 107 | 68 | 39 | 95 | 12 | ||

| Pancreatic cancinoma | 245 | 210 | 35 | 218 | 27 | ||

| Pancreatic Fibrosis | |||||||

| 0 | 168 | 79 | 89 | < 0.001 | 126 | 42 | < 0.001 |

| 1 | 181 | 152 | 29 | 158 | 23 | ||

| 2 | 204 | 182 | 22 | 201 | 3 | ||

| 3 | 56 | 55 | 1 | 56 | 0 | ||

| Pancreatic Steatosis | |||||||

| 0 | 292 | 258 | 34 | < 0.001 | 288 | 4 | < 0.001 |

| 1 | 205 | 156 | 49 | 181 | 24 | ||

| 2 | 95 | 48 | 47 | 64 | 31 | ||

| 3 | 17 | 6 | 11 | 8 | 9 | ||

Data are expressed as whole numbers, with P values from Fisher exact test

Table 3.

Risk scoring model for POPF

| Risk Factor | Risk Factor Weight | OR | Points contributed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic duct diameter | |||

| > 3 mm | 2.81 | 1.00 | 2 |

| ≤ 3 mm | 2.81 | 2.93 | 8 |

| Pancreatic Steatosis | |||

| 0 | 3.79 | 1 | 4 |

| 1 | 3.79 | 1.62 | 6 |

| 2 | 3.79 | 2.62 | 10 |

| 3 | 3.79 | 4.25 | 16 |

| Pancreatic Fibrosis | |||

| 3 | 1.60 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 1.60 | 1.41 | 2 |

| 1 | 1.60 | 1.99 | 3 |

| 0 | 1.60 | 2.81 | 4 |

Score max = 28, score min = 8

Low-risk: 8~14

Medium-risk: 15~21

High-risk: 22~28

Multivariate analysis and correlation of variables with POPF

Next, the 609 patients were divided into two groups. Data from 3/4 of the patients (n = 457) was used for a multivariate analysis and design model and the remaining 1/4 patient’s (n = 152) data was used for external validation for the logistic regression model. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis between the no-POPF group and POPF group, pancreatic duct diameter, PS and PF were independent factors with significance (Table 2). Patients with a pancreatic duct diameter > 3 mm were 0.341-fold risk of POPF compared with a diameter ≤ 3 mm. Both PS and PF are ordinal variables with numerical values from 0 to 3. The risk of POPF for each additional grade of PS is 1.621 times the lower grade. The risk of POPF for each additional grade of PF is 0.709 times the lower grade. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis between the no-CR-POPF group and CR-POPF group, pancreatic duct diameter, PS and PF were independent factors with significance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression models of independent risk factors for POPF

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No POPF VS. POPF | |||

| Pancreatic duct diameter | 0.34 | 0.19–0.59 | < 0.001 |

| Pancreatic Steatosis | 1.62 | 1.76–3.31 | < 0.001 |

| Pancreatic Fibrosis | 0.71 | 0.52–0.96 | 0.03 |

| No CR-POPF VS. CR-POPF | |||

| Pancreatic duct diameter | 3.33 | 1.96–5.64 | < 0.001 |

| Pancreatic Steatosis | 0.78 | 0.67–0.91 | 0.01 |

| Pancreatic Fibrosis | 2.42 | 1.47–3.97 | < 0.001 |

POPF risk score model

The weighting of each risk factor can be calculated based on the coefficient of each variable in the multivariate linear regression analysis. An odds ratio was also revealed in the multivariate linear regression analysis (Table 2). The authors assumed each risk factor contributes to POPF, with respect to weighting and odds ratios, and each variable was given a certain value by calculating the product of weighting times odds ratio (Table 3). Therefore, a simplified scoring model was generated, and 3 variables, pancreatic duct diameter, PS and PF, were included. The scores ranged from 8 to 28 and were stratified into into high-risk group (22~28 points), medium-risk group (15~21 points) and low-risk group (8~14 points) (Table 3). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (Fig. 1a) in the model design group shows that the Area under the curve (AUC) of the score was 0.868. The ROC curve in the external validation database (Fig. 1b) shows that the AUC of the score was 0.887.

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve. a: Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the predictive scoring model of the study group. Area under the receiver operator characteristics curve was 0.868. b: ROC curve for the predictive scoring model of the validate group. Area under the receiver operator characteristics curve was 0.88

Discussion

Postoperative pancreatic fistula continues to be a challenge in postoperative management. It increases patient distress, prolongs hospitalization and escalates the medical cost. In high volume institutions, POPF rates are high and are a primary detrimental factor causing modality and mortality. In this study, the overall incidence of POPF after PD was 23.2%, which was similar to the POPF rate in several large multicenter cohort studies [21–23].

Incorporating various risk factors into a scores model that predicts POPF risk has been reported by various groups [21, 24–31]. However, most of these models are built with single-center data, either not having been externally validated or having poor to fair performance at external validation, which restricts the applicability for clinical practice. The Fistula Risk Score (FRS) created by Callery and colleagues [27], which is based on gland texture, pancreatic duct diameter, intraoperative blood loss and definitive pathology, is the most cited and widely accepted POPF prediction model. It has been reported that the internal validation of AUC for Models I, II, and III are 0.936, 0.938 and 0.942, respectively. However, Olga and colleagues’ [32] recent research, based on NSQIP data, showed a Modified FRS (without blood loss) prediction model with poor external validation performance, where the AUC was only 0.62. In addition, included the most recently published Alternative FRS (without blood loss) study [33], these models rely heavily on pancreas texture to stratify risk groups. Despite pancreas texture being widely recognized as a strong prediction factor for POPF and applied universally in clinical practice, the subjective assessment is affected by many factors including but not limited to perceptions and experience, ultimately limiting its predictive value. To address these limitations, a new predictive model that can objectively reflect pancreas consistency and incorporate other risk factors, as well as predict and stratify POPF risk, needs to be developed. In this study, pancreatic texture was accurately evaluated based on the microstructure of the pancreas. In addition, the scoring model contain 3 main factors. We give each factor the appropriate score based on the relative weight of the three factors, which is more reasonable than the average score given in previous studies.

Pancreatic fibrosis and PS are well known for affecting the consistency of the pancreas. In this study’s systematic reviews, research indicated that low PF and high PS were risk factors for pancreatic leakage after pancreatic resection. One of the hypotheses is that the fiber and adipose tissue replace the normal pancreatic parenchyma destroying the normal microstructure of the pancreas, ultimately leading to changes in pancreatic texture [34–36]. Fatty infiltration in the pancreas makes the tissue more fragile, making anastomosis of the pancreas and intestine more easily disrupted, while deposition of fibrous tissue in the pancreas makes the tissue firm and reduces the complications in surgical operation [37]. Another hypothesis is that a fibrotic pancreas can decrease the incidence of POPF because of decreased pancreatic exocrine function. This study revealed that patients with severe PF had lower incidences of pancreatic fistula following PD and those with severe pancreatic fat infiltration had higher incidences. These results are consistent with several reported studies [16, 38, 39]. Many studies also concluded pancreatic duct diameter to be a major determinant of POPF [26, 40–42]. In this study, the data revealed that a pancreatic duct diameter less than 3 mm was a risk factor, with an odds ratio of 2.93 in POPF after PD. It is proposed that smaller pancreatic ducts are more prone to occlude or dehisce after a challenging duct-to-mucosa anastomosis procedure and obstructed or leaking pancreatic juice might corrode the pancreatic intestinal anastomosis, leading to pancreatic leakage. Wada et al. [43] suggested that using surgical microscope magnification for better visualization would decrease POPF rates.

The authors of this study were able to successfully develop and validate a POPF prediction model. This simplified scoring model consists of only three variables: PS, PF and pancreatic duct diameter. Using only three variables was shown to not sacrifice predictive capacity, where the AUC of the ROC curve for the model design group and external validation group were 0.868 and 0.887, respectively. This predictive model stratifies patients into three risk groups.

The limit of this study is that the three key variables used in the predictive model are intraoperative variables, limiting the model’s applicability for preoperative patient counseling. Next we should carry on a multicenter, prospective study to analyze whether this scoring system can guide clinicians in choosing the right pancreatic anastomosis. There are many ways to reconstruction the pancreas, but there is no uniform opinion on the choice of anastomosis. And we should also evaluate whether or not we can get accurate data of pancreatic fibrosis, pancreatic steatosis and pancreatic duct diameter during the surgery. After establishing the scoring system, we need to evaluate whether the surgeon can choose a more reasonable match according to the score.

Conclusion

Changes in pancreatic microstructure, such as severe fatty tissue infiltration in the pancreas, decreased pancreatic fibrosis and a smaller pancreatic duct diameter are the major risk factors for POPF following PD. A new predictive model can stratify patients into different POPF risk groups.

Additional files

Table S1. Demographic and Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Cohort (DOC 70 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Xuehan Liu, PhD, from the Department of Epidemiology and Biost atistics, School of Public Health, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, for her statistical support. We thank Dong Chen, PhD and Ke Zuo, PhD, from the School of Pathology, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, for their pathological analysis. We thank Chencheng Xie, PhD, from the Department of Internal Medicine, Sanford School of Medicine, University of South Dakota for his lingual support.

Abbreviations

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CP

Chronic Pancreatitis

- CR-POPF

Clinically Relevant Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula

- DP

Distal Pancreatectomy

- HE

hematoxylin and eosin

- LPD

Laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy

- OPD

Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy

- PC

Pancreatic Carcinoma

- PCT

Procalcitonin

- PD

Pancreatoduodenectomy

- PF

Pancreatic Fibrosis

- PG

Pancreaticogastrostomy

- PJ

Pancreaticojejunostomy

- POPF

Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula

- PS

Pancreatic Steatosis

- RBC

Red blood cell

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: GX, WM, QR. Acquisition of data: ZF, YM, JJ, HZ, GJ, HT, ZR, ZL, QR. Analysis and interpretation of data: GX, YM, ZL, WM. Drafting of the manuscript: GX, WM. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: QR. Statistical analysis: GX, WM, ZL. Obtained funding: QR, WM. Study supervision: QR, WM, ZL. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology and was carried out in accordance with the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Guo Xingjun, Zhu Feng and Yang Meiwen contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Zhang Leida, Phone: +023-65318301, Email: 2518569931@qq.com.

Wang Min, Phone: +27-8366-5295, Email: wangmin0013128@aliyun.com.

Qin Renyi, Phone: +27-8366-5295, Email: ryqin@tjh.tjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Vollmer CJ, Lewis RS, Hall BL, Allendorf JD, Beane JD, Behrman SW, Callery MP, Christein JD, Drebin JA, Epelboym I, et al. Establishing a quantitative benchmark for morbidity in pancreatoduodenectomy using ACS-NSQIP, the accordion severity grading system, and the postoperative morbidity index. Ann Surg. 2015;261(3):527–536. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gouma DJ, van Geenen RC, van Gulik TM, de Haan RJ, de Wit LT, Busch OR, Obertop H. Rates of complications and death after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg. 2000;232(6):786–795. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200012000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi SH, Moon HJ, Heo JS, Joh JW, Kim YI. Delayed hemorrhage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(2):186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tien YW, Lee PH, Yang CY, Ho MC, Chiu YF. Risk factors of massive bleeding related to pancreatic leak after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(4):554–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMillan MT, Vollmer CJ, Asbun HJ, Ball CG, Bassi C, Beane JD, Berger AC, Bloomston M, Callery MP, Christein JD, et al. The characterization and prediction of ISGPF grade C fistulas following Pancreatoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(2):262–276. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2884-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Ke N, Tan C, Zhang H, Wang X, Mai G, Liu X. Continuous versus interrupted suture techniques of pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Surg Res. 2015;193(2):590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Q, He XR, Tian JH, Yang KH. Pancreatic duct stents at pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis. Dig Surg. 2013;30(4–6):415–424. doi: 10.1159/000355982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jang JY, Chang YR, Kim SW, Choi SH, Park SJ, Lee SE, Lim CS, Kang MJ, Lee H, Heo JS. Randomized multicentre trial comparing external and internal pancreatic stenting during pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2016;103(6):668–675. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vin Y, Sima CS, Getrajdman GI, Brown KT, Covey A, Brennan MF, Allen PJ. Management and outcomes of postpancreatectomy fistula, leak, and abscess: results of 908 patients resected at a single institution between 2000 and 2005. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(4):490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stumpf S, Jaeger H, Graeter T, Oeztuerk S, Schmidberger J, Haenle MM, Kratzer W. Influence of age, sex, body mass index, alcohol, and smoking on shear wave velocity (p-SWE) of the pancreas. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2016;41(7):1310–1316. doi: 10.1007/s00261-016-0661-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pace A, de Weerth A, Berna M, Hillbricht K, Tsokos M, Blaker M, Pueschel K, Lohse AW. Pancreas and liver injury are associated in individuals with increased alcohol consumption. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(11):1241–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harada N, Ishizawa T, Inoue Y, Aoki T, Sakamoto Y, Hasegawa K, Sugawara Y, Tanaka M, Fukayama M, Kokudo N. Acoustic radiation force impulse imaging of the pancreas for estimation of pathologic fibrosis and risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219(5):887–894. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.07.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong D, Liu Y, Peng S, Sun X, Wang Z, Cheng J, Shen G, Zhang Y, Huang D. Binding pancreaticogastrostomy in laparoscopic central pancreatectomy: a novel technique in laparoscopic pancreatic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(2):715–720. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4265-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SE, Jang JY, Lim CS, Kang MJ, Kim SH, Kim MA, Kim SW. Measurement of pancreatic fat by magnetic resonance imaging: predicting the occurrence of pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2010;251(5):932–936. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d65483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoon JH, Lee JM, Lee KB, Kim SW, Kang MJ, Jang JY, Kannengiesser S, Han JK, Choi BI. Pancreatic steatosis and fibrosis: quantitative assessment with preoperative multiparametric MR imaging. RADIOLOGY. 2016;279(1):140–150. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tranchart H, Gaujoux S, Rebours V, Vullierme MP, Dokmak S, Levy P, Couvelard A, Belghiti J, Sauvanet A. Preoperative CT scan helps to predict the occurrence of severe pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2012;256(1):139–145. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318256c32c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golson ML, Loomes KM, Oakey R, Kaestner KH. Ductal malformation and pancreatitis in mice caused by conditional Jag1 deletion. GASTROENTEROLOGY. 2009;136(5):1761–1771. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathur A, Pitt HA, Marine M, Saxena R, Schmidt CM, Howard TJ, Nakeeb A, Zyromski NJ, Lillemoe KD. Fatty pancreas: a factor in postoperative pancreatic fistula. Ann Surg. 2007;246(6):1058–1064. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31814a6906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kloppel G, Sipos B, Luttges J. Spectrum of chronic pancreatitis. On the way to etiological classification. PATHOLOGE. 2005;26(1):59–66. doi: 10.1007/s00292-004-0733-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. SURGERY. 2005;138(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts KJ, Sutcliffe RP, Marudanayagam R, Hodson J, Isaac J, Muiesan P, Navarro A, Patel K, Jah A, Napetti S, et al. Scoring system to predict pancreatic fistula after Pancreaticoduodenectomy: a UK multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2015;261(6):1191–1197. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asbun HJ, Stauffer JA. Laparoscopic vs open pancreaticoduodenectomy: overall outcomes and severity of complications using the accordion severity grading system. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215(6):810–819. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song KB, Kim SC, Hwang DW, Lee JH, Lee DJ, Lee JW, Park KM, Lee YJ. Matched case-control analysis comparing laparoscopic and open pylorus-preserving Pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with Periampullary tumors. Ann Surg. 2015;262(1):146–155. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaujoux S, Cortes A, Couvelard A, Noullet S, Clavel L, Rebours V, Levy P, Sauvanet A, Ruszniewski P, Belghiti J. Fatty pancreas and increased body mass index are risk factors of pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. SURGERY. 2010;148(1):15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wellner UF, Kayser G, Lapshyn H, Sick O, Makowiec F, Hoppner J, Hopt UT, Keck T. A simple scoring system based on clinical factors related to pancreatic texture predicts postoperative pancreatic fistula preoperatively. HPB (Oxford) 2010;12(10):696–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen JY, Feng J, Wang XQ, Cai SW, Dong JH, Chen YL. Risk scoring system and predictor for clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(19):5926–5933. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.5926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Callery MP, Pratt WB, Kent TS, Chaikof EL, Vollmer CJ. A prospectively validated clinical risk score accurately predicts pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denbo JW, Orr WS, Zarzaur BL, Behrman SW. Toward defining grade C pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, risk factors, management and outcome. HPB (Oxford) 2012;14(9):589–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JY, Park JS, Kim JK, Yoon DS. A model for predicting pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy based on the international study group of pancreatic surgery classification. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2013;17(4):166–170. doi: 10.14701/kjhbps.2013.17.4.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kosaka H, Kuroda N, Suzumura K, Asano Y, Okada T, Fujimoto J. Multivariate logistic regression analysis for prediction of clinically relevant pancreatic fistula in the early phase after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21(2):128–133. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto Y, Sakamoto Y, Nara S, Esaki M, Shimada K, Kosuge T. A preoperative predictive scoring system for postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Surg. 2011;35(12):2747–2755. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1253-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kantor O, Talamonti MS, Pitt HA, Vollmer CM, Riall TS, Hall BL, Wang CH, Baker MS. Using the NSQIP pancreatic demonstration project to derive a modified fistula risk score for preoperative risk stratification in patients undergoing Pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224(5):816–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mungroop TH, van Rijssen LB, van Klaveren D, Smits FJ, van Woerden V, Linnemann RJ, de Pastena M, Klompmaker S, Marchegiani G, Ecker BL, et al. Alternative fistula risk score for Pancreatoduodenectomy (a-FRS): design and international external validation. Ann Surg. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Giniatullin RU, Revel-Muroz JA, Sovtchov SA, Kozel AI. Quantitative morphology of experimental fibrosis in canine pancreas after laser tunneling. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2010;150(1):92–95. doi: 10.1007/s10517-010-1078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsang SW, Zhang H, Lin C, Xiao H, Wong M, Shang H, Yang ZJ, Lu A, Yung KK, Bian Z. Rhein, a natural anthraquinone derivative, attenuates the activation of pancreatic stellate cells and ameliorates pancreatic fibrosis in mice with experimental chronic pancreatitis. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hori M, Takahashi M, Hiraoka N, Yamaji T, Mutoh M, Ishigamori R, Furuta K, Okusaka T, Shimada K, Kosuge T, et al. Association of pancreatic fatty infiltration with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2014;5:e53. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2014.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tajima Y, Kuroki T, Tsuneoka N, Adachi T, Kosaka T, Okamoto T, Takatsuki M, Eguchi S, Kanematsu T. Anatomy-specific pancreatic stump management to reduce the risk of pancreatic fistula after pancreatic head resection. World J Surg. 2009;33(10):2166–2176. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0179-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belyaev O, Munding J, Herzog T, Suelberg D, Tannapfel A, Schmidt WE, Mueller CA, Uhl W. Histomorphological features of the pancreatic remnant as independent risk factors for postoperative pancreatic fistula: a matched-pairs analysis. PANCREATOLOGY. 2011;11(5):516–524. doi: 10.1159/000332587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sugimoto M, Takahashi S, Kobayashi T, Kojima M, Gotohda N, Satake M, Ochiai A, Konishi M. Pancreatic perfusion data and post-pancreaticoduodenectomy outcomes. J Surg Res. 2015;194(2):441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braga M, Capretti G, Pecorelli N, Balzano G, Doglioni C, Ariotti R, Di Carlo V. A prognostic score to predict major complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2011;254(5):702–707, 707-708. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31823598fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugimoto M, Takahashi S, Gotohda N, Kato Y, Kinoshita T, Shibasaki H, Konishi M. Schematic pancreatic configuration: a risk assessment for postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17(10):1744–1751. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandini M, Bernasconi DP, Ippolito D, Nespoli L, Baini M, Barbaro S, Fior D, Gianotti L. Preoperative computed tomography to predict and stratify the risk of severe pancreatic fistula after Pancreatoduodenectomy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(31):e1152. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wada K, Traverso LW. Pancreatic anastomotic leak after the Whipple procedure is reduced using the surgical microscope. SURGERY. 2006;139(6):735–742. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Demographic and Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Cohort (DOC 70 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.