Abstract

Normal odd chain saturated fatty acids (OCSFA), particularly tridecanoic acid (n-13:0), pentadecanoic acid (n-15:0) and heptadecanoic acid (n-17:0), are normal components of dairy, beef and seafood. The ratio of n-15:0 to n-17:0 in ruminant foods (dairy and beef) is 2:1, while in seafood and human tissues it is 1:2, and their appearance in plasma is often used as a marker for ruminant fat intake. Human elongases encoded by ELOVL1, ELOVL3, ELOVL6, and ELOVL7 catalyze biosynthesis of the dominant even chain saturated fatty acids (ECSFA), however, there are no reports of elongase function on OCSFA. ELOVL transfected MCF7 cells were treated with n-13:0, n-15:0, or n-17:0 (80 μΜ) and products analyzed. ELOVL6 catalyzed elongation of n-13:0 → n-15:0 and n-15:0 → n-17:0; and ELOVL7 had modest activity toward n-15:0 (n-15:0 → n-17:0). No elongation activity was detected for n-17:0 → n- 19:0. Our data expand ELOVL specificity to OCSFA, providing the first molecular evidence demonstrating ELOVL6 as the major elongase acting on OCS n-13:0 and n-15:0 FA. Studies of food intake relying on OCS as biomarker should consider endogenous human metabolism when relying on OCSFA ratios to indicate specific food intake.

Keywords: elongase, tridecanoic acid (n-13:0), pentadecanoic acid (n-15:0), heptadecanoic acid (n-17:0), intake biomarker

Introduction

Normal odd chain saturated fatty acids (OCSFA), particularly tridecanoic acid (n-13:0), pentadecanoic acid (n-15:0) and heptadecanoic acid (n-17:0), are normal components of ruminant products, specifically dairy and beef (1; 2). They are also found in non-ruminant sources such as seafood (3). In recent years, n- 15:0 and n-17:0 are considered biomarkers of dairy fat intake, mainly because their concentrations in serum and adipose tissue correspond with dairy intake (4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9). Not only serum and adipose tissue, they are also found to incorporate in other human tissues such as plasma, red blood cells (RBCs) and liver (2). Recent studies showed that n-15:0 and n-17:0 are biomarkers of not only dairy but also seafood (3) and dietary fiber intake (10), which again indicates OCSFA is applicable in estimation of food intake. Additionally, n-15:0 and n-17:0 are positively associated with insulin sensitivity and inversely associated with Type 2 diabetes in both cohort (6; 11) and case-control studies (12; 13; 14), which contrasts with links between incident diabetes and prevalent even chain saturated (ECS) FA intake such as stearic acid (n- 18:0). Circulating OCSFA and/or their relative concentrations (e.g. ratios) may be useful as a physiological index of health with careful attention to their origin and endogenous metabolism (2; 12; 14; 15).

Concentrations of n-13:0, n-15:0 and n-17:0 in general milk products in the U.S. are about 0.1%, 1.2% and 0.6% of total FA, respectively (1). They are likely to be originated primarily via ruminal bacteria. The ratio of n-15:0 to n-17:0 in U.S. dairy fat is 2:1 (16; 17; 18). In contrast, is approximately 1:2 in both freshwater and marine fishes (3; 19; 20; 21) as well as in human plasma (10; 12; 15; 18). Comparable amount of OCSFA are found in vegan RBCs (22). Because dairy fat is the predominant source of OCSFA in the U.S., it is likely that endogenous fatty acid interconversion alters their ratio via elongation, most importantly as n-15:0→-n-17:0 (2; 18; 23); they may also arise by de novo synthesis. Current endogenous synthesis pathways of OCSFA are well summarized in previous reviews (2; 18; 23). Among them, one theory proposes an α-oxidation of ECSFA by intermediate hydroxylation/removal of one carbon from carboxylic end (18). However, few details are available on the gene products responsible for OCSFA biosynthesis, unlike well-known biochemical routes to ECSFA.

In ECSFA metabolism, FA elongation follows a four-step cycle comprised of condensation, reduction, dehydration and second time reduction which occurs in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (24). Mammalian FA elongases ELOVL1–7 (elongation of very long chain fatty acids) work in the first and rate-limiting condensation step and all have substrate specificities and tissue specific expression distribution. Among them, ELOVL1, 3, 6 and 7 preferentially act on saturated and monounsaturated FA (SFA and MUFA); ELOVL2 and 5 are known to work on polyunsaturated FA (PUFA); while ELOVL4 elongate very long chain FA (VLCFA) with more than 24 carbons regardless of unsaturation (24; 25; 26). Currently established substrate specificities of ELOVL towards ECSFA are as follows: ELOVL6, n-12:0→n-14:0→n- 16:0→n-18:0 (25; 27); ELOVL1, 3 and 7, n-18:0→n-20:0→→→n-26:0; ELOVL4, n-26:0→→30:0 (24; 25). ELOVL6 catalyzes n-16:0→n-18:0 in ruminant mammary cells (28) and is expressed ubiquitously in bovine mammary epithelial cells (29). ELOVL6 genetic variants are reportedly associated with insulin sensitivity in a Spanish population (30).

Unlike the well-studied ECSFA, endogenous metabolism of OCSFA once ingested is not well characterized with respect to the relevant genes encoding enzymes that catalyze their interconversion. As circulating n-15:0 and n-17:0 are regarded as biomarkers of dairy, dietary fiber and seafood intake, we aimed to establish specificity of the ELOVL responsible for elongation of OCSFA of quantitative significance in the human diet. We tested the hypothesis that ELOVL6 is specific to n-13:0→n-15:0→n- 17:0 compared to the other ELOVL known to operate on straight chain fatty acids. We adopted an approach analogous to previous successful studies that established numerous novel functions for PUFA biosynthetic genes by transient or stable transfection of the open reading frame (ORF) into MCF7 cells and other models (31; 32; 33; 34; 35; 36; 37; 38). To test ELOVLx (ELOVL1, 3, 6 and 7) function we constructed expression vectors and transiently transfected them individually into MCF7 cells as a human cell host.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents

Fatty acids (n-13:0, n-15:0 and n-17:0) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Solvents are HPLC grade for fatty acid extraction and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and Burdick & Jackson (Muskegon, MI). Cell culture media, fetal bovine serum (FBS) and other cell culture reagents were obtained from Life Technologies (NY), Corning (MA) and Thermo Fisher Scientific (MA).

ELOVL6 sequence and phylogenetic analysis

The amino acid (AA) sequences of ELOVL6 from various vertebrate species are obtained from GenBank accession numbers (Table S1). The AA sequence of human ELOVL6 was aligned with several other vertebrate ELOVL6 sequences using ClustalX2.1 software (39). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method (40) with MEGA7 (41). Confidence in the resulting phylogenetic tree branch topology was measured by bootstrapping test method with 1000 replicates (42).

ELOVL expression vector constructs

The open reading frame of ELOVL transcripts (ELOVL1, ELOVL3, ELOVL6 and ELOVL7) were cloned into a pcDNA3.1(+) expression vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA) containing cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. The specific ELOVL gene synthesis and cloning was carried out by GenScript service, NJ. The GenBank accession numbers of ELOVL mRNA (NM) and protein (NP) are provided in Table S1. Plasmid DNA used for transfection assays was extracted and purified using Plasmid Midi Kit (QIAGEN, MD). The extracted DNA was verified by DNA sequencing and stored at - 20°C. DNA sequencing was performed at Cornell University life sciences core laboratories center using the Applied Biosystems automated 3730 DNA analyzer.

Mammalian cell culture, transfection, and fatty acid supplementation

MCF7 human breast cancer cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified environment with 5% CO2, using minimum essential medium alpha (MEM-a) with 10% FBS and 10mM buffer [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1- piperazineethanesulfonic acid; HEPES] as described previously (32; 34).

MCF7 cells were seeded at 1× 106 cell density into 60mm cell culture dishes. After 48h, when they reach 60–80% confluency, cells were washed with 1× PBS and ELOVL (ELOVL1, 3, 6 and 7) transcripts were transfected individually using Polyplus (NY) jetPRIME transfection reagent. Empty vector was used as control. According to the jetPRIME reagent kit protocol, 4μg of Vector (control) or ELOVL DNA was transfected into cells along with 200μl jetPRIME buffer, 8μl jetPRIME reagent, and 5ml growth media. After 24h, the transfected MCF7 cells were supplemented with 80 μΜ of bovine serum albumin (BSA) bound OCSFA substrates (n-13:0, n-15:0 and n-17:0). Briefly, to make BSA bound substrates, n-13:0, n-15:0 and n-17:0 were dissolved in absolute ethanol to make 100mM FA stock. FA stock (200 l) was then mixed with FA free BSA in 1× PBS (4.4% w/w) and incubated overnight at 37°C. BSA bound OCSFA were filtered using 0.22 μm syringe, and diluted to 80 μΜ with non-FBS MCF7 media then added to cells. After additional 24 h incubation, cells were washed twice with 1 × PBS, harvested by trypsinization and supernatant removed after centrifuging.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

RNA was isolated from harvested MCF7 cell pellets using E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit I (Omega Bio-tek Inc, GA). The RNA quantity and quality was verified by micro spectrophotometer Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific). cDNA was synthesized from 1 g of RNA using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies, NY). Synthesized cDNA was then used as template for RT-PCR reactions (43).

RT-PCR

Gene specific primers ELOVL1–7 were designed using PrimerQuest software (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA), primer sequences and annealing temperatures are shown in Table S2. RT- PCR amplification reactions were performed using EmeraldAmp GT PCR Master Mix (Clontech, CA) using gradient thermal cycler (Eppendorf, NY). PCR products were separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis stained with ethidium bromide, and bands were visualized under UV light. GAPDH was used as control gene.

Fatty acid extraction and analysis

Fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) from the harvested MCF7 cell pellets were prepared according to the modified one-step method of Garces and Mancha (44). FAME were structurally identified by gas chromatography (GC) - chemical ionization, electron ionization (EI) mass spectrometry (MS) and EIMS/MS using a Saturn 2000 mass spectrometer attached to a Varian Star 3400 gas chromatograph (45). FAME were quantified by GC-flame ionization detector (GC-FID) (Hewlett-Packard). An equal weight FAME mixture, GLC462 (Nu-Check Prep, Inc.), was used to calculate response factors of all fatty acids. Percent conversion of substrates (S) to products (P) was calculated as: [(P) / (S + P)] * 100, and normalized to the control group.

Statistical analysis

All treatments were performed using two biological replicates; the mean of three technical replicate GC- FID analyses were used for each biological replicate and no data was excluded. In numerous earlier studies, we used an analogous approach with MCF7 transfection and fatty acid treatment with 2–3 biological replicates for functional characterization of PUFA biosynthetic genes (31; 32; 33; 34); this approach is comparable to functional characterization studies conducted by others (35; 36; 37; 38). Values generated using averages across the two biological replicates are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis of comparisons between multiple groups was performed using OriginPro 8 Software (OriginLab Corporation, MA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Tukey Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test was used to analyze significant differences between groups. Differences when P<0.05 are considered significant.

Results

Amino acid sequence and phylogenetic analysis of ELOVL6

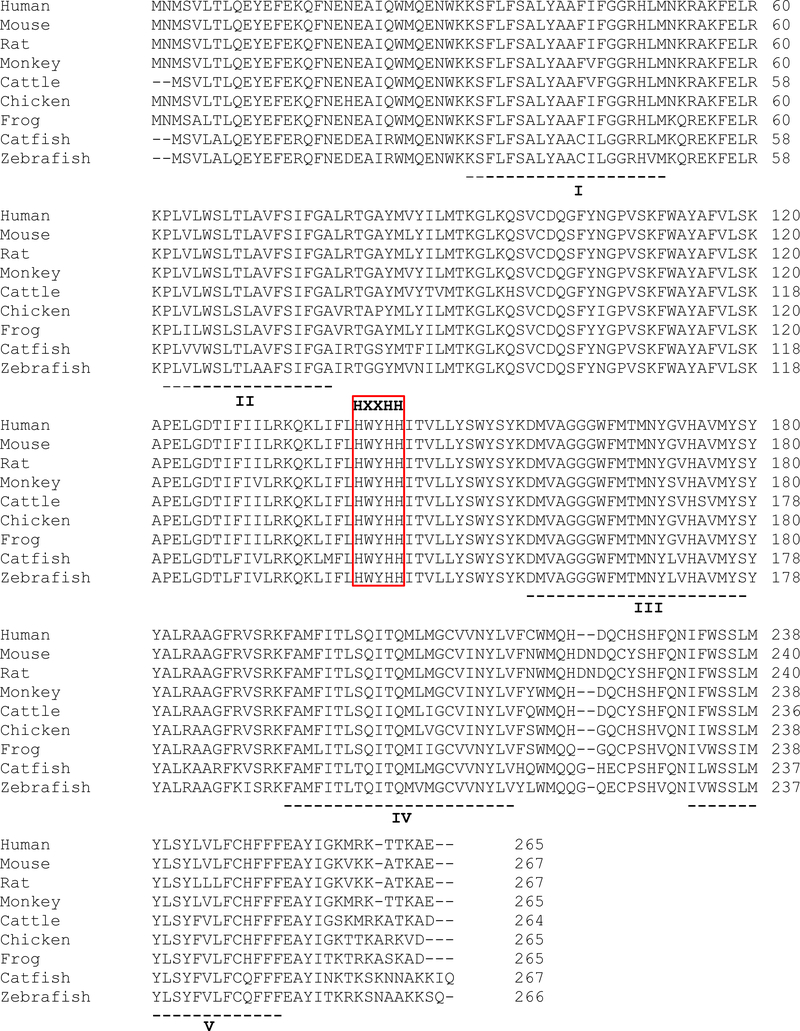

The human ELOVL6 cDNA (NM_024090.2) consist of a 798 base pair (bp) ORF, encoding a protein of 265 AA (NP_076995.1). As shown in Figure 1, human ELOVL6 shares >90% AA sequence identity with other vertebrate ELOVL6 sequences. The human ELOVL6 shared 98.11%, 96.98%, 96.60% and 93.16% identity, with monkey, mouse, rat and cattle sequences respectively. All vertebrate ELOVL6 possessed five transmembrane domains (I-V) found among elongases (46) as well as the conserved histidine box HXXHH motif characteristic of elongase families (47; 48; 49).

Figure 1: Alignment of amino acid (AA) sequences of ELOVL6 from human and other vertebrates.

The AA sequences of various species obtained from GenBank accession numbers were aligned using ClustalX 2.1. The well conserved histidine motif HXXHH is depicted in the box. The dotted lines with Roman numerals indicate the putative transmembrane regions (46).

A phylogenetic tree was constructed by comparing the AA sequences of ELOVL6 from various vertebrates (Figure 2). As expected, the human ELOVL6 grouped with primates, while rodents (rat and mouse) and fish (catfish and zebrafish) grouped together.

Figure 2: Phylogenetic tree of ELOVL6 from human and other organisms.

The tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates in MEGA7. The numbers represent the frequencies (%); and horizontal branch length is proportional to AA substitution rate per site. Each species was followed by its NCBI Reference Sequence (NP).

Distribution of SFA in MCF7 cells

MCF7 cells are high in ECSFA n-16:0 (16.63 ± 0.43%) and n-18:0 (12.98 ± 0.52%), but contain only trace amount of OCSFA n-17:0 (0.22 ± 0.02%) and n-13:0 and n-15:0 are at undetectable amounts (unpublished data). Table 1 summarizes when MCF7 cells are dosed with 80 μΜ of specific OCSFA, cells readily uptake OCSFA in the order of n-17:0 > n-15:0 > n-13:0.

Table 1.

Uptake Efficiency of OCSFA by MCF7 cells.

| OCSFA | n-13:0 | n-15:0 | n-17:0 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Uptake Efficiency1 | 3.276 | 0.002 | 20.334 | 0.136 | 27.733 | 0.175 |

Uptake Efficiency (%) = wt (BCFA uptake) / wt (total fatty acids excluding OCSFA)×100%

MCF7 cells have trace amount of basal OCSFA; control cells readily uptake OCSFA when treated with 80 μΜ of albumin bound individual OCSFA, and was in the order of n-17:0 > n-15:0 > n-13:0.

Data from two biological replicates.

Transient Transfection ELOVL gene expression

Figure S1 shows ELOVL (ELOVL1 to ELOVL7) gene expression in wild type (WT), control (empty pcDNA3.1(+) vector) and ELOVLx transiently transfected cells. The cells were incubated with A) 80pM n-13:0 B) 80μM n-15:0 and C) 80μM n-17:0. ELOVL1 expression was higher in ELOVL1 transfected cells; similarly ELOVL3, ELOVL6 and ELOVL7 expression are higher in ELOVL3, 6 and 7 transfected cells. These results show transfections were successful.

Elongation, n-13:0→n-15:0

MCF7 cells transiently expressing ELOVL1, ELOVL3, ELOVL6 and ELOVL7 and control (empty vector) were incubated with 80 μΜ of albumin bound n-13:0 OCSFA. MCF7 cells have native elongase activity, so the gain of function is compared to control (Figure 3). The cells expressing ELOVL6 showed significantly increased activity towards n-13:0 (131.19 ± 5.52 (%)). No gain of activity was seen with other elongases.

Figure 3: ELOVLx activity, n-13:0→n-15:0.

Percent conversion of fatty acid substrate n-13:0 into elongation product n-15:0 (ratios shown, calculated as [n-15:0]/[n-13:0 ]+ [n-15:0]) was measured in MCF7 cells and normalized to control group. ELOVL1, 3 and 7 showed no activity towards n-13:0 (n-13:0→-n-15:0). ELOVL6 had significantly higher catalytic activity towards n-13:0 (n-13:0→-n-15:0). Data from two biological replicates. a-b: P<0.05.

Elongation, n-15:0→n-17:0

MCF7 cells transiently expressing ELOVL1, ELOVL3, ELOVL6 and ELOVL7 and control (empty vector) were incubated with 80 μΜ of albumin bound n-15:0 OCSFA. MCF7 cells have native elongase activity, so the gain of function is compared to control (Figure 4). The cells expressing ELOVL6 showed significantly increased activity towards n-15:0 (129.51 ± 1.74 (%)), followed by moderate activity in ELOVL7 cells (113.99 ± 1.30 (%)). No gain of activity was seen with ELOVL1. Elongation activity was lower than control in the ELOVL3 cells though not different than ELOVL1 cells.

Figure 4: ELOVLx activity, n-15:0→n-17:0.

Percent conversion of fatty acid substrate n-15:0 into elongation product n-17:0 (ratios shown, calculated as [n-17:0]/([n-15:0] + [n-17:0]) was measured in MCF7 cells and normalized to control group. ELOVL1 showed no activity towards n-15:0 (n- 15:0→n-17:0). ELOVL3 reduced activity towards n-15:0 (n-15:0→n-17:0) compared to control though it was not different than ELOVL1. ELOVL6 had significantly higher catalytic activity towards n-15:0 (n-15:0→n-17:0). ELOVL7 showed moderate activity towards n-15:0 (n-15:0→n-17:0). Data from two biological replicates. a-d: P<0.05.

Interconversion, n-17:0→n-15:0 but not n-19:0

MCF7 cells transiently expressing ELOVL1, ELOVL3, ELOVL6 and ELOVL7 and control (empty vector) were incubated with 80 μΜ of albumin bound n-17:0 OCSFA. All MCF7 cells (ELOVL1, ELOVL3, ELOVL6 and ELOVL7 and control) readily uptake n-17:0 but none of the cells showed elongation activity towards n-17:0; n-19:0 is not detected. While n-15:0 is not detectable in untreated cells, incubation with n-17:0 results in n-15:0 appearance at approximately equal amounts ([15:0]/([15:0]+[17:0]) ~ 3%) regardless of ELOVLx transfection, suggesting that β-oxidation is a route of n-17:0 conversion.

Discussion

Our results confirm the hypothesis that ELOVL6 is the primary ELOVL with activity toward OCSFA, specifically catalyzing n-13:0→n-15:0 and n-15:0→n-17:0. Further, ELOVL7 has moderate activity toward n-15:0→n-17:0. ELOVL1 had no activity toward any OCSFA, and no ELOVL catalyzed n- 17:0→n-19:0, consistent with the trace amount of n-19:0 in human tissue. ELOVL3 significantly reduced activity compared to control but not compared to ELOVL1 which was not different than control. MCF7 cells have native elongation activity, thus it is plausible that ELOVL3 may have inhibited that native conversion, possibly by non-active substrate binding. The magnitude of the effect is small, however.

Our AA sequence alignments of ELOVL6 showed a high degree of conservation among evolutionarily distant related genomes (human to zebrafish). The histidine rich motif and all five transmembrane regions are conserved from human to zebrafish. The pattern of ELOVL6 homology among several vertebrate species even with distant phylogeny points to similar metabolic conservation.

ELOVL6 belongs to a highly conserved microsomal enzyme family that is involved in fatty acid biosynthesis. ELOVL6 activity characterized by cloning of mammalian ELOVL6 ORF into expression vector and expressing the vector in mammalian cells shows that ELOVL6 specifically catalyzes the elongation of even chain saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids with chain length 12, 14, and 16 carbons (46; 50). ELOVL6 is found to be ubiquitously expressed in mice and bovine tissues (29; 46), and plays a role in energy metabolism and insulin sensitivity (27), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (51), breast cancer (52), pulmonary fibrosis (53) and squamous cell carcinoma of the lung (54).

The endogenous synthesis of OCSFA via α-oxidation of ECSFA has been previously reported (18; 55; 56). In an adipocyte differentiation study, both kinetic and 13C palmitate labelled experiments showed significant increase in the synthesis of OCSFA via α-oxidation (55). The differentiating adipocytes converted 13C palmitate (n-16:0) to n-15:0, showing that OCSFA were endogenously synthesized from n-16:0 by α-oxidation in this cell type. This conversion happened only in the cells and not in cell culture media (55). Similarly, Su et al. showed differentiating adipocytes when incubated with [9,−10-3H]n-16:0 resulted in the production of radiolabeled [3H]n-15:0 via α-oxidation (57). Casteels et al. (58) proposed α- oxidation mechanism might play a role in the formation of OCSFA in the brain. An in-vivo experiment with rats infused with n-18:0 showed ~70% (p < 0001) increase in the n-17:0 levels in the serum compared to a control rat group (59). Our results show that specific ELOVL6 or 7 may operate on these nascent products α-oxidation n-13:0 and n-15:0 but not on n-17:0 to further alter OCSFA profile (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Even chain saturated fatty acid (ECSFA) and Odd chain saturated fatty acid (OCSFA) biosynthesis in vertebrates.

ELOVL6 catalyzes elongation of n-12:0 to n-18:0, whereas ELOVL3 catalyzes elongation of n-18:0 to n-20:0. Depicted in red font color: ELOVL6 elongates OCSFA n- 13:0→n-15:0 and n-15:0→n-17:0. ELOVL7 (shown as 7) has moderate activity (n-15:0→n-17:0). Palmitic acid (n-16:0), the major product of fatty acid synthase (FASN), and α-oxidation of ECSFA to OCSFA are also shown. FASN, fatty acid synthase; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; N.R., no reaction.

Here we found overlapping activity for ELOVL6 and ELOVL7; both had substrate specificity for n-15:0. Elongases in several species are known to share common overlapping functions (49; 60; 61). Previously it has been shown that mammalian ELOVL1, ELOVL3 and ELOVL7 share common substrates (25; 49; 62; 63). ELOVL1 elongates SFA of chain lengths n-18:0 to n-26:0, with the highest activity toward n-22:0 FA, whereas, ELOVL3 and ELOVL7 were found to elongate n-16:0 to n-22:0 FA, with the highest activity toward n-18:0 FA (62; 63; 64).

The relatively small biological replicate size (n=2) in our study has consistently yielded reliable results in our previous work (31; 32; 33; 34). For functional characterization studies, others have used a single assay to support conclusions based on identification of a novel fatty acid product by chromatography with subsequent calculation of a conversion ratio (35; 36; 37; 38), thus greater confidence in matching biological duplicates of the present results is warranted. Our uses of duplicates with consistently small standard deviations in FAME analysis, as well as validation of ELOVLx transfection efficiency via RT-PCR, support a similar level of confidence in the present results. Finally, we note that our data on normal polyunsaturated fatty acids (31; 32; 33; 34) and ECSFA (data not shown) faithfully replicates that of others.

In conclusion, we provide the first molecular evidence demonstrating ELOVL6 is the major elongase acting on OCSFA, with specificity toward n-13:0 and n-15:0. Modest activity was found for ELOVL7 toward n-15:0. The present study expands ELOVL substrate specificity range to OCSFA. Nutrition studies considering these fatty acids as markers of specific food intake should consider interconversion of OCSFA in light of these findings, particularly genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and targeted gene studies as they associate circulating OCSFA levels with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and other polymorphisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. Hui Gyu Park, Jiyao Zhang and Lei Liu for assistance with experiment protocols.

Financial Support

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 AT007003 from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health and the Office of Dietary Supplements. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Jensen RG (2002) The composition of bovine milk lipids: January 1995 to December 2000. Journal of dairy science 85, 295–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfeuffer M, Jaudszus A (2016) Pentadecanoic and Heptadecanoic Acids: Multifaceted Odd-Chain Fatty Acids. Adv Nutr 7, 730–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang DH, Jackson JR, Twining C et al. (2016) Saturated Branched Chain, Normal Odd-Carbon-Numbered, and n-3 (Omega-3) Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Freshwater Fish in the Northeastern United States. J Agric Food Chem 64, 7512–7519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albani V, Celis-Morales C, Marsaux CF et al. (2016) Exploring the association of dairy product intake with the fatty acids C15:0 and C17:0 measured from dried blood spots in a multipopulation cohort: Findings from the Food4Me study. Mol Nutr Food Res 60, 834–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brevik A, Veierod MB, Drevon CA et al. (2005) Evaluation of the odd fatty acids 15:0 and 17:0 in serum and adipose tissue as markers of intake of milk and dairy fat. European journal of clinical nutrition 59, 1417–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santaren ID, Watkins SM, Liese AD et al. (2014) Serum pentadecanoic acid (15:0), a short-term marker of dairy food intake, is inversely associated with incident type 2 diabetes and its underlying disorders. The American journal of clinical nutrition 100, 1532–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smedman AE, Gustafsson IB, Berglund LG et al. (1999) Pentadecanoic acid in serum as a marker for intake of milk fat: relations between intake of milk fat and metabolic risk factors. The American journal of clinical nutrition 69, 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolk A, Furuheim M, Vessby B (2001) Fatty acid composition of adipose tissue and serum lipids are valid biological markers of dairy fat intake in men. J Nutr 131, 828–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolk A, Vessby B, Ljung H et al. (1998) Evaluation of a biological marker of dairy fat intake. The American journal of clinical nutrition 68, 291–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weitkunat K, Schumann S, Nickel D et al. (2017) Odd-chain fatty acids as a biomarker for dietary fiber intake: a novel pathway for endogenous production from propionate. The American journal of clinical nutrition 105, 1544–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel PS, Sharp SJ, Jansen E et al. (2010) Fatty acids measured in plasma and erythrocyte- membrane phospholipids and derived by food-frequency questionnaire and the risk of new-onset type 2 diabetes: a pilot study in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)- Norfolk cohort. The American journal of clinical nutrition 92, 1214–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forouhi NG, Koulman A, Sharp SJ et al. (2014) Differences in the prospective association between individual plasma phospholipid saturated fatty acids and incident type 2 diabetes: the EPIC-InterAct case-cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endo 2, 810–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krachler B, Norberg M, Eriksson JW et al. (2008) Fatty acid profile of the erythrocyte membrane preceding development of Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 18, 503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroger J, Zietemann V, Enzenbach C et al. (2011) Erythrocyte membrane phospholipid fatty acids, desaturase activity, and dietary fatty acids in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. The American journal of clinical nutrition 93, 127–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawczynski C, Kleber ME, Marz W et al. (2015) Saturated fatty acids are not off the hook. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 25, 1071–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dewhurst RJ, Moorby JM, Vlaeminck B et al. (2007) Apparent recovery of duodenal odd- and branched-chain fatty acids in milk of dairy cows. Journal of dairy science 90, 1775–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fievez V, Colman E, Castro-Montoya JM et al. (2012) Milk odd- and branched-chain fatty acids as biomarkers of rumen function-An update. Anim Feed Sci Tech 172, 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkins B, West JA, Koulman A (2015) A review of odd-chain fatty acid metabolism and the role of pentadecanoic Acid (c15:0) and heptadecanoic Acid (c17:0) in health and disease. Molecules 20, 2425–2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roubal WT (1963) Tuna Fatty Acids.2. Investigations of Composition of Raw and Processed Domestic Tuna. J Am Oil Chem Soc 40, 215–218. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gruger EH, Stansby ME, Nelson RW (1964) Fatty Acid Composition of Oils from 21 Species of Marine Fish Freshwater Fish + Shellfish. J Am Oil Chem Soc 41, 662–667. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Njinkoue JM, Barnathan G, Miralles J et al. (2002) Lipids and fatty acids in muscle, liver and skin of three edible fish from the Senegalese coast: Sardinella maderensis, Sardinella aurita and Cephalopholis taeniops. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 131, 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kornsteiner M, Singer I, Elmadfa I (2008) Very low n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid status in Austrian vegetarians and vegans. Ann Nutr Metab 52, 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riserus U, Marklund M (2017) Milk fat biomarkers and cardiometabolic disease. Curr Opin Lipidol 28, 46–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kihara A (2012) Very long-chain fatty acids: elongation, physiology and related disorders. J Biochem 152, 387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guillou H, Zadravec D, Martin PG et al. (2010) The key roles of elongases and desaturases in mammalian fatty acid metabolism: Insights from transgenic mice. Prog Lipid Res 49, 186–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang JY, Kothapalli KS, Brenna JT (2016) Desaturase and elongase-limiting endogenous long- chain polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care 19, 103–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuzaka T, Shimano H (2009) Elovl6: a new player in fatty acid metabolism and insulin sensitivity. J Mol Med (Berl) 87, 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi HB, Wu M, Zhu JJ et al. (2017) Fatty acid elongase 6 plays a role in the synthesis of long-chain fatty acids in goat mammary epithelial cells. Journal of dairy science 100, 4987–4995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen S, He H, Liu X (2017) Tissue expression profiles and transcriptional regulation of elongase of very long chain fatty acid 6 in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Plos One 12, e0175777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morcillo S, Martin-Nunez GM, Rojo-Martinez G et al. (2011) ELOVL6 genetic variation is related to insulin sensitivity: a new candidate gene in energy metabolism. Plos One 6, e21198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park HG, Park WJ, Kothapalli KS et al. (2015) The fatty acid desaturase 2 (FADS2) gene product catalyzes Delta4 desaturation to yield n-3 docosahexaenoic acid and n-6 docosapentaenoic acid in human cells. Faseb J 29, 3911–3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park HG, Kothapalli KSD, Park WJ et al. (2016) Palmitic acid (16:0) competes with omega-6 linoleic and omega-3 a-linolenic acids for FADS2 mediated Delta6-desaturation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1861, 91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park WJ, Kothapalli KS, Reardon HT et al. (2012) A novel FADS1 isoform potentiates FADS2- mediated production of eicosanoid precursor fatty acids. J Lipid Res 53, 1502–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park WJ, Kothapalli KS, Lawrence P et al. (2011) FADS2 function loss at the cancer hotspot 11q13 locus diverts lipid signaling precursor synthesis to unusual eicosanoid fatty acids. Plos One 6, e28186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morais S, Castanheira F, Martinez-Rubio L et al. (2012) Long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis in a marine vertebrate: ontogenetic and nutritional regulation of a fatty acyl desaturase with Delta4 activity. Biochim Biophys Acta 1821, 660–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castro LF, Monroig O, Leaver MJ et al. (2012) Functional desaturase Fads1 (Delta5) and Fads2 (Delta6) orthologues evolved before the origin of jawed vertebrates. Plos One 7, e31950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie D, Chen F, Lin S et al. (2014) Cloning, functional characterization and nutritional regulation of Delta6 fatty acyl desaturase in the herbivorous euryhaline teleost Scatophagus argus. Plos One 9, e90200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geay F, Tinti E, Mellery J et al. (2016) Cloning and functional characterization of Delta6 fatty acid desaturase (FADS2) in Eurasian perch (Perca fluviatilis). Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 191, 112–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP et al. (2007) Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4, 406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33, 1870–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Felsenstein J (1985) Confidence-Limits on Phylogenies - an Approach Using the Bootstrap. Evolution 39, 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yan Y, Wang Z, Greenwald J et al. (2017) BCFA suppresses LPS induced IL-8 mRNA expression in human intestinal epithelial cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 116, 27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garces R, Mancha M (1993) One-step lipid extraction and fatty acid methyl esters preparation from fresh plant tissues. Anal Biochem 211, 139–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ran-Ressler RR, Lawrence P, Brenna JT (2012) Structural characterization of saturated branched chain fatty acid methyl esters by collisional dissociation of molecular ions generated by electron ionization. J Lipid Res 53, 195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsuzaka T, Shimano H, Yahagi N et al. (2002) Cloning and characterization of a mammalian fatty acyl-CoA elongase as a lipogenic enzyme regulated by SREBPs. J Lipid Res 43, 911–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin M, Monroig O, Navarro JC et al. (2017) Molecular and functional characterisation of two elovl4 elongases involved in the biosynthesis of very long-chain (>C24) polyunsaturated fatty acids in black seabream Acanthopagrus schlegelii. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 212, 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li S, Monroig O, Wang T et al. (2017) Functional characterization and differential nutritional regulation of putative Elovl5 and Elovl4 elongases in large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Sci Rep 7, 2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng T, Li H, Han N et al. (2017) Functional Characterization of Two Elongases of Very Long- Chain Fatty Acid from Tenebrio molitor L. (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Sci Rep 7, 10990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moon YA, Shah NA, Mohapatra S et al. (2001) Identification of a mammalian long chain fatty acyl elongase regulated by sterol regulatory element-binding proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry 276, 45358–45366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laggai S, Kessler SM, Boettcher S et al. (2014) The IGF2 mRNA binding protein p62/IGF2BP2–2 induces fatty acid elongation as a critical feature of steatosis. J Lipid Res 55, 1087–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feng YH, Chen WY, Kuo YH et al. (2016) Elovl6 is a poor prognostic predictor in breast cancer. Oncology letters 12, 207–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sunaga H, Matsui H, Ueno M et al. (2013) Deranged fatty acid composition causes pulmonary fibrosis in Elovl6-deficient mice. Nature communications 4, 2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marien E, Meister M, Muley T et al. (2016) Phospholipid profiling identifies acyl chain elongation as a ubiquitous trait and potential target for the treatment of lung squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 7, 12582–12597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roberts LD, Virtue S, Vidal-Puig A et al. (2009) Metabolic phenotyping of a model of adipocyte differentiation. Physiological genomics 39, 109–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kondo N, Ohno Y, Yamagata M et al. (2014) Identification of the phytosphingosine metabolic pathway leading to odd-numbered fatty acids. Nature communications 5, 5338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Su X, Han X, Yang J et al. (2004) Sequential ordered fatty acid alpha oxidation and Delta9 desaturation are major determinants of lipid storage and utilization in differentiating adipocytes. Biochemistry 43, 5033–5044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Casteels M, Sniekers M, Fraccascia P et al. (2007) The role of 2-hydroxyacyl-CoA lyase, a thiamin pyrophosphate-dependent enzyme, in the peroxisomal metabolism of 3-methyl-branched fatty acids and 2-hydroxy straight-chain fatty acids. Biochemical Society transactions 35, 876–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jenkins BJ, Seyssel K, Chiu S et al. (2017) Odd Chain Fatty Acids; New Insights of the Relationship Between the Gut Microbiota, Dietary Intake, Biosynthesis and Glucose Intolerance. Sci Rep 7, 44845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee SH, Stephens JL, Paul KS et al. (2006) Fatty acid synthesis by elongases in trypanosomes. Cell 126, 691–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y, Botolin D, Christian B et al. (2005) Tissue-specific, nutritional, and developmental regulation of rat fatty acid elongases. J Lipid Res 46, 706–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ohno Y, Suto S, Yamanaka M et al. (2010) ELOVL1 production of C24 acyl-CoAs is linked to C24 sphingolipid synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, 18439–18444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sassa T, Kihara A (2014) Metabolism of very long-chain Fatty acids: genes and pathophysiology. Biomolecules & therapeutics 22, 83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Naganuma T, Sato Y, Sassa T et al. (2011) Biochemical characterization of the very long-chain fatty acid elongase ELOVL7. FEBS letters 585, 3337–3341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.