Abstract

Background

A persistent hyaloid artery is a rare fetal remnant. Several complications such as amblyopia, vitreous hemorrhage, and retinal detachment have been reported. Here, we present a case of vitreous hemorrhage with a persistent hyaloid artery.

Case presentation

A healthy 16-year-old male presented with blurred vision in his left eye. Vitreous hemorrhage occurred and absorbed spontaneously. Slit-lamp examination demonstrated a Mittendorf’s dot and fundus examination revealed a persistent hyaloid artery. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed a Bergmeister’s papilla. The blood flow of the persistent hyaloid artery via the Bergmeister’s papilla was found by OCT angiography.

Conclusion

The persistent hyaloid artery should be considered as a cause of spontaneous vitreous hemorrhage of young healthy patient. The OCT angiography will be a useful noninvasive approach to confirm the patency of the persistent hyaloid artery.

Keywords: Persistent hyaloid artery, Hyaloid artery, Vitreous hemorrhage, Case report

Background

The process of intraocular vascularization begins with the entry of the hyaloid artery into the optic disc cup through the fetal fissure. Under normal conditions, the artery atrophies at its midpoint and retracts to its end at the optic disc and the posterior pole of lens at term [1].

A persistent hyaloid artery (PHA) results from the failure of apoptosis of hyaloid vascular system. Despite numerous growth factors and molecules implicated on few studies, factors associated to apoptosis of the hyaloid artery are still unknown [2]. The PHA is associated with rare but severe vitreous hemorrhage (VH), retinal detachment and cataract [2–8].

In previous reports, fundus photography, fluorescein angiography (FAG), optical coherence tomography (OCT) and Doppler ultrasound were used to diagnose and to check the blood flow of the PHA [3–6, 8]. OCT angiography can visualize peripapillary vessels by detecting the movement of red-blood cells [9]. Herein, we present the case of VH from the PHA which was confirmed by OCT angiography.

Case presentation

A healthy 16-year-old Korean male presented to our clinic in September 26, 2018 with blurred vision in his left eye. He had neither past medical history nor trauma history.

On ocular examination, best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 0 logMAR in his right eye and Hand motion in his left eye. Intraocular pressures were 17 mmHg in the right eye and 13 mmHg in the left eye. The fundus was invisible due to massive VH in the left eye (Fig. 1a). His blood pressure and laboratory test results including coagulating factors were normal.

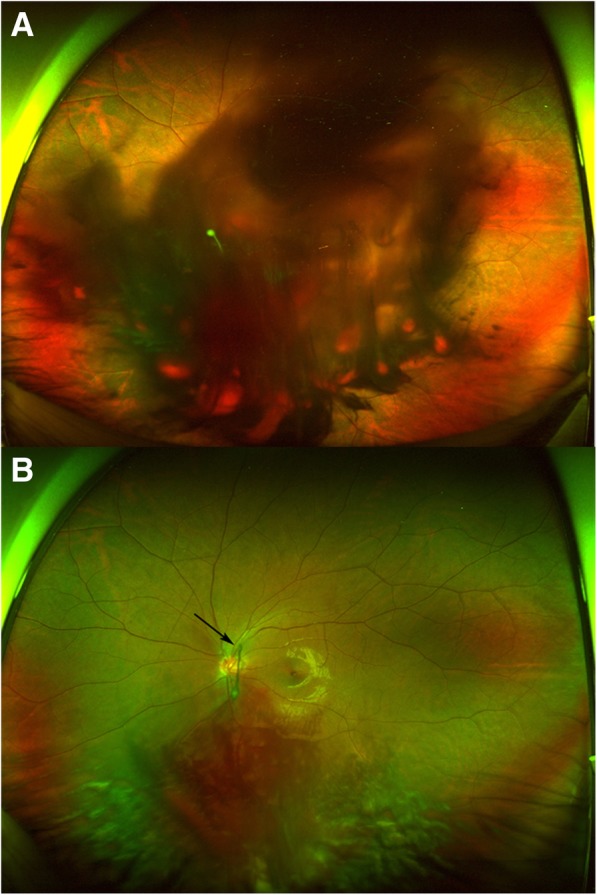

Fig. 1.

Wide field fundus photography of the patient (a) Massive vitreous hemorrhage was seen at the initial visit. b Vitreous hemorrhage was partially absorbed after 2 weeks. The persistent hyaloid artery was seen (arrow)

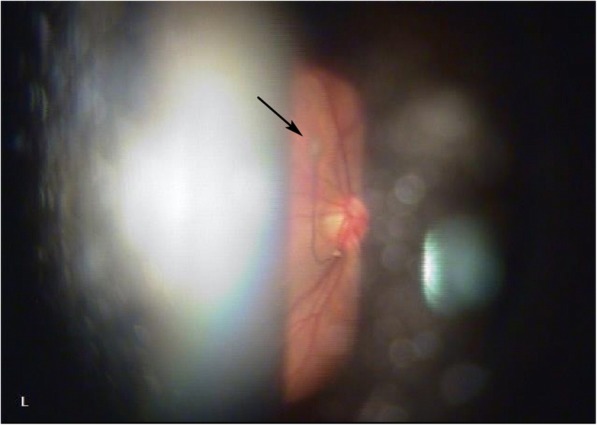

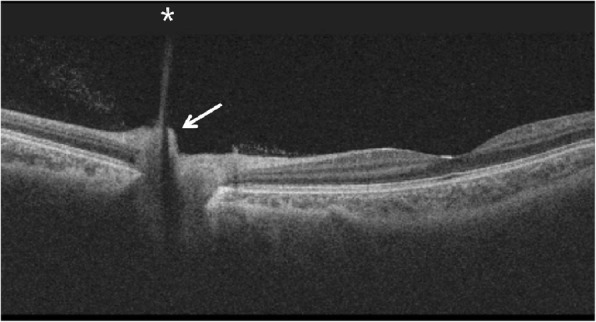

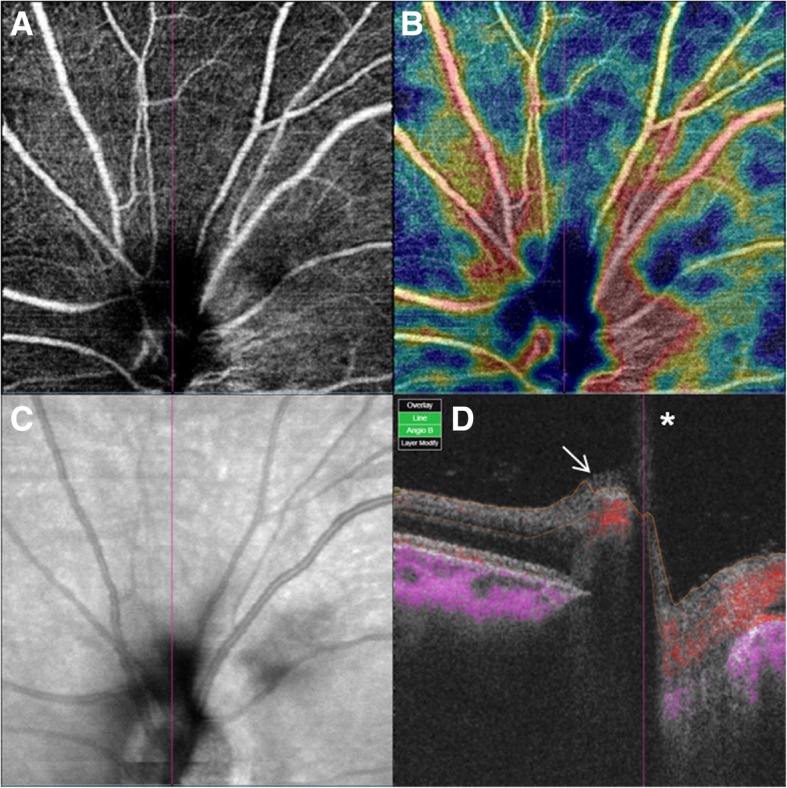

The VH partially decreased 2 weeks later and the BCVA improved to 0.4 logMAR in the left eye. No cause of VH other than the PHA was found (Fig. 1b). Slit-lamp examination demonstrated a Mittendorf’s dot located in the inferior nasal quadrant of the posterior lens capsule in the left eye (Fig. 2). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed hyporeflective tubular structure of the PHA and elevated tissue structure of the optic nerve (Bergmeister’s papilla) (Fig. 3). OCT angiography could not demonstrate the active blood flow of the PHA due to the technical limitation. However, we could find the blood flow in the Bergmeister’s papilla (Fig. 4). The VH was spontaneously disappeared after 2 months. No serious disorders have been observed in the left eye during the follow-up period.

Fig. 2.

Slit-lamp photography was taken at 2 weeks after the initial visit. The point of insertion of the persistent hyaloid artery on the inferior nasal quadrant of the posterior lens capsule (Mittendorf’s dot) is indicated by the arrow

Fig. 3.

Optical coherence tomography of optic nerve of the left eye of the patient taken at 2 weeks after the initial visit reveals the posterior aspect of the persistent hyaloid artery. OCT shows hyporeflective tubular structure of the persistent hyaloid artery (asterisk) and an elevated tissue structure (Bergmeister’s papilla) (arrow). (Swept Source DRI OCT TRITON. Topcon Medical Systems, Inc. Oakland, USA)

Fig. 4.

Optical coherence tomography angiography of the optic nerve head of the left eye of the patient taken at 3 weeks after the initial visit. a Segmented at the superficial retinal plexus. b Color-coded vessel density map. c Projection image of optic disc. d Cross-sectional OCT angiography. The blood flow was detected from Bergmeister’s papilla (arrow), but the blood flow of the persistent hyaloid artery (asterisk) was not confirmed. (Swept Source DRI OCT TRITON. Topcon Medical Systems, Inc. Oakland, USA)

Discussion and conclusions

The PHA is a rare fetal remnant from developmental abnormalities during the seventh month of gestation. The hyaloid artery is a branch of the ophthalmic artery which is a branch of internal carotid artery. It is present in the optic canal and extends from the optic disc to the crystalline lens via the vitreous humor. It branches to form a network of capillaries, the tunica vasculosa lentis, which is prominent at about 9 weeks’ gestation [10, 11]. In healthy fetuses, gradual regression of the hyaloid artery starts at 18 weeks, and by 29 weeks, the hyaloid artery disappears and leaves Cloquet’s canal [12, 13].

The failure of regression of the hyaloid artery is called PHA which may be either partial or complete. The remnant of the anterior portion is called Mittendorf’s dot which is located on the inferonasal quadrant of posterior lens capsule and the remnant of the posterior portion is called Bergmeister’s papilla which is present at the optic disc usually composed of glial tissue [10, 14]. The entire hyaloid artery which extends from the optic disc to the posterior lens capsule is rare. The patent hyaloid vessels may supply a part of retinal tissue [13]. Hence, the condition is prone to repeated episodes of VH, and contraction of the fibrovascular mass may exert traction on the retina, causing retinal detachment [14].

For diagnosis, slit-lamp examination, fundus examination, fluorescein angiography (FAG), OCT and Doppler ultrasound have been used [3–8, 13, 15]. Gonçalves et al. [4] and Chen et al. [5] used FAG to check patency and leakage of the PHA, while Goncalves et al. reported no blood flow, Chen et al. showed proximal filling. Our patient refused to FAG, so we took OCT angiography which was noninvasive to the patient in order to check the blood flow of the PHA.

Various mechanisms such as the traction force during the rapid eye movement phase of sleep [5], external trauma to the globe [4, 16], and spontaneous development [6] have been reported. In our case, the mechanism of the occurrence of VH from the PHA is unclear. We could not find the presence of posterior vitreous detachment or vitreoretinal traction after VH disappeared. Since the patient had a history of recent excessive weight training, we suppose that VH was caused by rupture of the PHA by elevated blood pressure or physical force due to excessive exercise.

To our knowledge, it is the first report that OCT angiography was used to check blood flow of the PHA. Our OCT angiography could show the blood flow only in the Bergmeister’s papilla. Since OCT angiography has low axial resolution, the blood flow in the vitreous cavity is difficult to observe with OCT angiography.Therefore, the blood flow inside the Bergmeister’s papilla, which is mainly composed of glial tissue and has no normal blood flow, can be an evidence of patency of the PHA. Another possible reason why the blood flow was observed only in the Bergmeister’s papilla is that the blood flow of the PHA was actually only in the proximal part, like the case of Chen et al. [5].

In conclusion, the PHA should be considered as a cause of vitreous hemorrhage in young and healthy patients. The OCT angiography will be a useful noninvasive test to confirm the patency of the PHA.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Abbreviations

- BCVA

Best corrected visual acuity

- FAG

Fluorescein angiography

- OCT

Optical coherence tomography

- PHA

Persistent hyaloid artery

- VH

Vitreous hemorrhage

Authors’ contributions

HJ assembled and analyzed the data. JK was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. SK was responsible for the design of the study and cared for the patient. All of the authors reviewed the data and participated in the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors have no proprietary or financial interest in any of the products used in this study.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting the findings are contained within the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents for publication of this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hansol Jeon, Email: a3346209@hallym.or.kr.

Jinsoo Kim, Email: jinsoo@hallym.or.kr.

Soonil Kwon, Phone: 82-10-9075-5854, Email: magicham@hallym.or.kr.

References

- 1.Frederick AJ. Ocular anatomy, embryology, and teratology. Philadelphia: Harper & Row; 1982. p. 378. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saint-Geniez M, D'Amore PA. Development and pathology of the hyaloid, choroidal and retinal vasculature. The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 2004;48(8–9):1045–1058. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041895ms. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azrak C, Campos-Mollo E, Lledó-Riquelme M, Ibañez FA, Toldos JJ. Vitreous haemorrhage associated with persistent hyaloid artery. Arch Soc EspOftalmol. 2011;86(10):331–334. doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonçalves A, Cruysberg JRM, Draaijer RW, Sellar PW, Aandekerk AL, Deutman AF. Vitreous haemorrhage and other ocular complications of a persistent hyaloid artery. Doc Ophthalmol. 1996;92(1):55–59. doi: 10.1007/BF02583277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen TL, Yarng SS. Vitreous hemorrhage from a persistent hyaloid artery. Retina. 1993;13(2):148–151. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199313020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delaney WVJ. Prepapillary hemorrhage and persistent hyaloid artery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;90(3):419–421. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(14)74928-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Önder F, Coşsar CB, Gültan E, Kural G. Vitreous hemorrhage from the persistent hyaloid artery. J AAPOS. 2000;4:190–191. doi: 10.1016/S1091-8531(00)70014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sundararajan M, Jansen ME, Gupta M. Unilateral persistence of the hyaloid artery causing Vitreopapillary and Vitreomacular traction. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(5):e180221. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akil H, Falavarjani KG, Sadda SR, Sadun AA. Optical coherence tomography angiography of the optic disc; an overview. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2017;12(1):98–105. doi: 10.4103/2008-322X.200162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones H. Hyaloid remnants in the eyes of premature babies. Br J Ophthalmol. 1963;47:39–44. doi: 10.1136/bjo.47.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell CA, Risau W, Drexler HC. Regression of vessels in the tunica vasculosalentis is initiated by coordinated endothelial apoptosis: a role for vascular endothelial growth factor as a survival factor for endothelium. Dev Dyn. 1998;213:322–333. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199811)213:3<322::AID-AJA8>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Achiron R, Kreiser D, Achiron A. Axial growth of the fetal eye and evaluation of the hyaloid artery: in utero ultrasonographic study. Prenat Diagn. 2000;20:894–899. doi: 10.1002/1097-0223(200011)20:11<894::AID-PD949>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jay US, Ashish S, Santonu C. Persistent hyaloid artery with an aberrant peripheral retinal attachment: a unique presentation. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2013;6(1):58–60. doi: 10.4103/0974-620X.111924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smirniotopoulos JC, Bargallo N, Mafee MF. Differential diagnosis of leukokoria: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1994;14:1059–1079. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.14.5.7991814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Little WS. A case of persistent hyaloid artery. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1881;3:211–213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yap EY, Buettner H. Traumatic rupture of a persistent hyaloids artery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:225–227. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(14)73993-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings are contained within the manuscript.