Abstract

Public health professionals have long played a vital—albeit underappreciated—role in shaping, not simply using, US Census data, so as to provide the factual evidence required for good governance and health equity. Since its advent in 1790, the US Census has constituted a key political instrument, given the novel mandate of the US Constitution to allocate political representation via a national decennial census. US Census approaches to categorizing and enumerating people and places have profound implications for every branch and level of government and the resources and representation accorded across and within US states. Using a health equity lens to consider how public health has featured in each generation’s political battles waged over and with census data, this essay considers three illustrations of public health’s engagement with the enduring ramifications of three foundational elements of the US Census: its treatment of slavery, Indigenous populations, and the politics of place. This history underscores how public health has major stakes in the values and vision for governance that produces and uses census data.

The US Census is—and was designed to be—a potent political instrument.1–3 The first census ever to be mandated by a country’s constitution, its declared role, since its advent in 1790, was and is to count the US population every 10 years to determine, via legislatively determined algorithms, the democratic allocation of political representation in the US Congress.1–3 Governance, moreover, requires resources, and US Census data continually inform taxation policies and allocation of government funds.1–3 Affecting political power, governance, and the distribution of resources for the public welfare, the census is critical for the public’s health.4,5

The census is also fundamental for population health data, including calculation of death rates, birth rates, and fertility rates.6–8 Indeed, only in 1946, after World War II, did oversight for vital statistics shift from the US Census Bureau to a newly formed National Office of Vital Statistics located in the US Public Health Service.1,6,7 Census data also provide denominators to quantify rates of diseases and injuries, monitor health inequities, and create sampling frames for myriad public health and social surveys.1,6–9 The uses of US Census data for public health are both legion and obvious.

The field of public health, however, has not simply used census data: it has shaped them. Historical scholarship has long recognized the role of public health in informing census conduct, content, and interpretation, for both good and ill,1–3,6,8 despite these contributions curiously being ignored by contemporary public health, population science, and epidemiology textbooks,10–16 with some exceptions.8,17 Yet, as I will argue, it is—and has always been—part of the purview of public health to engage with the US Census, both politically and empirically, regarding whom the census counts (and excludes), what categories it uses, and what demarcations of place it uses.

To make my case, I offer three illustrations that engage with three enduring issues built into the very constitutional mandate for a US decennial census: slavery, Indigenous populations, and the politics of place.1–3 The three examples I consider are (1) the 1840 census, slavery, and insanity18–20; (2) Indigenous populations and inaccurate census and health data21–24; and (3) the public health roots of census tracts.25,26

As a brief reminder, Article I, Section I of the US Constitution states: “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and a House of Representatives.”27 But whereas Article I, Section 3 fixed the number of senators to “two Senators from each state,” regardless of population, Article I, Section 2 declared that:

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding the whole Number of free persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other persons. The actual enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct.27

States’ place-based Congressional power thus was distributed in relation to three groups, defined in relation to political standing:

1. Free persons (included): beginning with the first census, all free men, women, and children were counted, including indentured servants and those ineligible to vote (as determined by state, not federal, laws, noting that in 1790, only free adult men with property could vote).28–30

2. American Indians (excluded based on sovereignty): “Indians not taxed” were Indigenous persons who lived under their own governments and thus were treated as noncitizens and not counted or taxed; Congress granted citizenship and voting rights to all American Indians (regardless of tribal affiliation) only in 1924.21,23,31

3. Enslaved persons (partial inclusion): the infamous Three-Fifths Compromise (whose words do not explicitly refer to slavery or race/ethnicity) reflected the contending interests of legislators who sought to enhance versus curb the power of the slave states; the compromise awarded these states enhanced political representation in Congress via partial, as opposed to zero, inclusion of enslaved persons, who were not allowed to vote.1,2,32

The legacies of these political distinctions remain manifest in how, among US racial/ethnic groups, US Indigenous populations and US descendants of enslaved persons have both the worst health status33,34 and most flawed census data.1–3

1840 CENSUS: SLAVERY, INSANITY, AND FLAWED DATA

Slavery and population health data lay at the heart of a raging controversy about the 1840 Census, which seemingly indicated that freedom drove Black Americans mad.18–20 Although this episode is well-known to historians of the census and of slavery,1,18,35 many in public health are unaware of its role in the rise of that era’s nascent public health and statistical associations, in part through their efforts to improve census data1,17,20

In brief, results of the 1840 Census, which newly introduced questions about the presence of persons then termed “insane and idiots,” provided evidence that the prevalence of insanity among the “colored” population (almost exclusively Black Americans), but not the White population, increased with latitude and was highest in the northernmost states.18–20 For example, in Maine, 1 in 14 Blacks were counted as “insane and idiots,” as compared with 1 in 5650 in Louisiana36; regionally, 1 in 162 Blacks in the North were pegged as “insane and idiots,” versus 1 in 1558 for the South.1 By contrast, 1 in 970 Whites nationally were classified as “insane and idiots,” with little geographic variation.1,18

Slavery supporters predictably trumpeted these data as proof that Blacks constitutionally were incapable of handling liberty.18–20,35 Epitomizing these arguments, the proslavery Secretary of State John C. Calhoun (1782–1850) proclaimed:

Here is proof of the necessity of slavery. The African is incapable of self-care and sinks into lunacy under the burden of freedom. It is a mercy to give him guardianship and protection from mental death.19(p473)

Slavery opponents, by contrast, took these data as evidence that some serious error affected the US Census data.1,18–20 Supporting these concerns, Edward Jarvis (1803–1884)—who in 1839 had cofounded the American Statistical Association with Lemuel Shattuck (1793–1859)1,6,18—carefully reviewed the census returns. His key finding was the startling discovery that insane Blacks, especially in Northern states, were tallied in locales with no Black population—leading to vastly inflated rates of their insanity.1,18,19,36 Despite national controversy and Congressional investigation, and despite ample documentation of gross errors (albeit no evidence of deliberate falsification of data), the US Census never officially declared these data to be erroneous.1,36

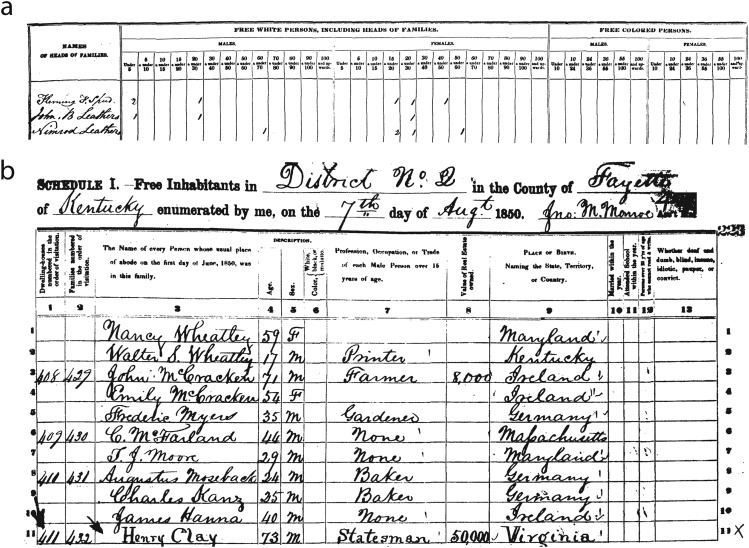

Subsequent scholars have shown that the errors arose because of the poor layout of the 80-column table in which enumerators recorded the census data.1,18,36 The 1840 Census schedule allotted only one line per household (Figure 1).18,36,37 In this one cramped line, poor formatting and typesetting made it easy for enumerators to err by wrongly entering data for elderly Whites deemed to be “idiots” into the column intended for “colored” “idiots.” Consequently, inclusion of a small number of White persons labeled as “idiots” in the “colored” column would have little impact in states with large Black populations (i.e., the US South), but would, by contrast, hugely inflate the prevalence in states with small Black populations (i.e., the US North)18,36—thereby producing a spurious correlation of “insanity” with both latitude and enslavement.18,36

FIGURE 1—

1840 vs 1850 US Census Schedule Showing Transformation From (a) One Line per Household (1840) to (b) One Line per Individual, by Household (1850)

Note. The 1850 census was informed by public health expertise and implemented in the wake of the national controversy involving inaccurate 1840 Census data—invoked by proponents of slavery—that erroneously suggested higher insanity rates among free versus enslaved Black Americans.18–20

Source. US Census Bureau.37

Partly as a result of this contentious debacle, Congress established a Census Board to plan and implement the 1850 Census. In 1849, this board invited two leading professionals to help improve the process: Lemuel Shattuck, from the American Statistical Association, and Archibald Russell of the American Geographical and Statistical Society.1 Prompting Shattuck’s invitation was the innovative census he had conducted for Boston, Massachusetts, in 1845.38 His work was inspired by Edwin Chadwick’s (1800–1890) groundbreaking 1842 Report on Sanitary Conditions in England,39 a precedent-setting government collection of population health data that led to England’s 1848 Public Health Act, the world’s first national legislation to establish a Central Board of Health.40,41 As Hetzel recounts in her history of US vital statistics, for the Boston census, Shattuck

introduced the basic innovation of making the primary census unit the individual rather than the family. Instead of describing the whole family on a single line, he had given a line on the schedule to each person, which made it easy to record the name, age, birthplace, marital condition, and occupation, and to assemble the data afterward in new and more revealing types of tables.6(p48)

Building on the Boston 1845 Census, Shattuck next published in 1850, at the request of the Massachusetts legislature, an equally path-breaking sanitary survey now known as the “Shattuck Report,”42 which was the first-ever US report to call for the creation of state health departments and local boards of health.40,43

Shattuck’s experience with these public health surveys led to a fundamental change in the conduct of the US Census, whereby the national schedules were restructured to collect individual-level data, within households, as opposed to the prior practice of one line per household (Figure 1).1,6,37 This novel approach not only improved accuracy but also—as in the case of the Boston Census—facilitated new approaches to tabulating the data (e.g., presenting age-specific rates6) and led to Congress allocating more resources for conducting the census and analyzing its data.1

US CENSUS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES: WHO COUNTS?

If accurate census counts and vital statistics are an indicator of political inclusion and civic standing,1,2,44 then the woeful state of these data for Indigenous peoples since the onset of American settler colonialism stands as a profound indictment of histories of exclusion and subjugation.21–24,31 Accounting for this statistical travesty requires reckoning with histories of conquest, territory, sovereignty, and policies of cultural annihilation, as well as the complex politics of race, ethnicity, nationality, ancestry, genealogy, and “blood.”2,22,23,31,45

A full rendering of the who, what, where, and how of census exclusion, counting, and miscounting of Indigenous peoples is beyond the scope of this article.1,2,21–24,31 However, starting with the 1790 Constitutional exclusion of “Indians not taxed,” the US Census was deeply involved in whether and how Indigenous peoples literally counted for the US polity.1,2,21–24,31 Initial grounds for exclusion were premised on sovereignty, with the census counting only persons subject solely to US law.1,2,21,23 Federal interest in the number of Indians (taxed and untaxed) increased after Congress passed the “Removal Act of 1830,” which enabled the US government to force the exchange of Indian lands in any state or territory.1,2,21,23,31

Definitions of which Indians counted for the census—as Indians and also as citizens—were also affected by marriage and miscegenation laws.46 In the Western regions, for example, territorial and state governments initially had a vested interest in allowing White men to marry and have children with Indian women, as a way of transferring Indian land to US property, under jurisdiction of laws that vested in husbands the rights to control women’s property and family inheritance.46 Passage of antimiscegenation laws prohibiting White–Indian marriages, however, began to pick up in the 1860s (since they were less useful as Whites solidified control of Indian lands). By the 1890s, they emulated the long-standing White–Black antimiscegenation laws, which ensured that if White men impregnated enslaved Black women (whether by rape or consensual union), the women could make no claims for marital support nor could their children have any claims to White property (with the “one-drop” rule additionally ensuring that any such children counted solely as “Black”).46

By the late 19th century, the growing federal control over the full expanse of the US continent31 led the US Census to adopt new methods of defining and counting American Indians. In the 1880 Census, enumerators were instructed to measure “the degree to which an Indian had adopted a European way of life” and to distinguish between “full-blood tribal members and individuals of mixed racial or tribal origin.”23(p72) Fearful that these questions were a pretext for establishing further federal control, many Indians refused to participate.23,31 “Blood purity” was also key to the 1887 General Allotment (Dawes) Act, which granted citizenship to Indians who agreed to sell land previously held in trust in reservations, provided that they had “a certain degree (purity) of Indian blood.”23(p72),31 The net effect was to institutionalize the role of the US government in creating a “blood quantum” regime, still extant, to determine who counts as being Indian (above and beyond any Indigenous reckonings).23,31,45

These census approaches to counting Indians entrenched both classification and misclassification of Indigenous populations in both census records and vital statistics.21–24 In 1894, the US Census published its first major “Report on Indians Taxed and Not Taxed in the United States, Except Alaska,” which presented limited vital statistics and acknowledged that prior counts were severely flawed, grossly underestimating the Indian population.2,21,23 Granting of US citizenship to all US Indians in 1924 had no impact on census accuracy (other to change the 1930 Census report title from stating it was about “Indians ‘in’ the United States” to “Indians ‘of’ the United States”23[p75]). In the 1950 Census, enumerators were supposed to include as American Indians “anyone who was one-quarter or more blood quantum,” albeit with no instructions as to how this was to be ascertained.21(p45)

The profound shift in the 1960 Census from the enumerator-defined to self-defined identity, as tied to its growing use of a mailed census form (fully implemented in the 1970 Census)1,2 led to a sharp rise in US persons claiming American Indian “ancestry” or “race,” categories not clearly distinguished in the census instructions.21–23 Notably, the number of persons selecting the US Census racial category of “American Indian or Alaska Native” nearly tripled between 1980 and 2000 (rising from 1.5 million to 4.3 million), whereas the larger number selecting this group for “ancestry” remained steady (upward of 5 million to 7 million).22 In the 2000 Census—the first to permit selection of one or more racial/ethnic categories—2.5 million people selected only American Indian or Alaska Native, and another 1.9 million selected this option plus some other race(s)21; the data for the years 2012 to 2016 yield similar counts.47

What are the implications of these contested categories for population health—and population health data—for American Indians and Alaska Natives? In a word: terrible.24,31,48 Both numerators and denominators for health data for US Indigenous people have long been vitally marred, with grossly inaccurate counts of birth, deaths, and the total population leading to severely biased rates.23,24 In 2016, the National Center for Health Statistics issued an update on the validity of “race and Hispanic-origin reporting” in US death certificates, comparing results for the period 1999 to 2011, versus earlier reports for the years 1979 to 1989 and 1990 to 1998.49 Notably, misclassification of deaths “remained high at 40% for the American Indian or Alaska Native population (AIAN),” whereas it shrank to 3% for both the Hispanic and Asian or Pacific Islander populations and was negligible for the White and Black populations.49(p1) Correcting for this misclassification significantly increased the AIAN-to-White death rate ratio, from a deficit of 84% to an excess of 116%.49 Other research has shown that updated bridged intercensal population estimates, routinely used for denominators for population health data, significantly overestimate the AIAN Hispanic population50 and that, from the 2000 Census to the 2010 Census, persons categorized as AIAN had the highest rate of changing their racial/ethnic group.51

There are no easy “fixes” to these complex AIAN data issues. However, in the past decade public health researchers—working in multidisciplinary, multiagency groups, including Indigenous organizations—have been constructively collaborating to improve AIAN vital statistics, cancer registry, and other health data by cross-linking across these and other government data sources.22,50,52–58 This work has led to correcting AIAN rate underestimates for mortality due to stroke, overdoses, and other causes of death,50,52–54 and also for injuries55 and hospital discharges56—and can also help inform new efforts to improve US Census AIAN data via such data linkages.50,52–60

Such initiatives are both complex and costly. They also are long overdue—and necessitate full inclusion of Indigenous health expertise and organizations at every step.22,31,57–60 Nearly 230 years after the US Constitution washed its hands of “Indians not taxed,” it is only right that US tax dollars be expended to rectify the US government’s culpability for inequitable social and health conditions among US Indigenous populations and their inadequate documentation and monitoring. As one of the US Census posters for 2000 aptly declared, depicting a Pueblo Indian buffalo dance ceremony, “Generations are counting on this” (Figure 2).61

FIGURE 2—

Buffalo Dance—Allan Houser (1914–1994)

Source. Census 2000: US Census Marketing Posters.61

SANITARY AREAS, CENSUS TRACTS, AND HEALTH INEQUITIES

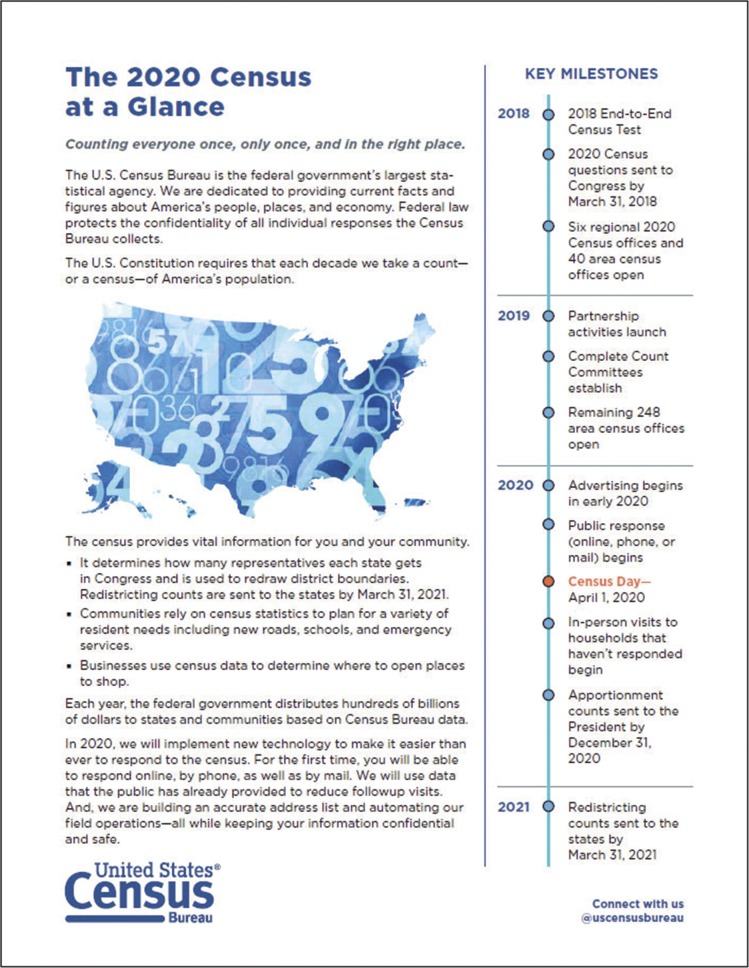

As affirmed by the US Census Bureau promotion of the 2020 Census (Figure 3),62 local and state governments, businesses, and community groups rely on US Census data to determine needs, guide investments, provide services, and advocate for state and federal funding—including via members of Congress whose districts are ultimately determined by the politics of census counts and boundaries.1–5 A key unit of census geography informing these discussions and debates is the census tract, which is the smallest US Census unit with individual-level data on both social and economic characteristics (as well as data on housing units).25,63 Designed to encompass populations relatively homogenous in social characteristics, census tracts optimally include 4000 persons (range = 1200–8000) and comprise “small, relatively permanent statistical subdivisions of a county or equivalent entity” whose “primary purpose . . . is to provide a stable set of geographic units for the presentation of statistical data.”63

FIGURE 3—

Counting Everyone Once, Only Once, and in the Right Place

Source. US Census Bureau: The 2020 Census at a Glance.62

The vital role of public health—and concerns about health inequities—in establishing the census tract as a key element of census geography, however, is rarely emphasized.25,26 In the United States, the late 19th-century influx of immigrants and rapid growth of cities and slums galvanized interest in community conditions and health.9,25,38,40–43 In 1895, the Chicago, Illinois–based Hull House settlement house produced the first-ever detailed US mapping of community conditions, which they linked to health.9,17,64

Their maps inspired others to follow suit, including the young W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) at the beginning of his career; his work with the Hull House women65 influenced his own path-breaking 1899 study The Philadelphia Negro, which likewise combined community surveys, maps, and health data.66 At that time, the typical local unit of city geography was the ward, whose boundaries, as a voting district, created a direct link between places, politics, and power.9,25 As Du Bois showed in riveting figures he created for the Negro Exhibit of the American Section at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900,67 ward data could be used to reveal the existence of socioeconomic gradients in health, including among the Black population, as he demonstrated with data from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.68

However, a serious problem with using wards as a unit of community geography was precisely their political contingency, since political parties could—and did—manipulate (i.e., gerrymander) ward boundaries to gain electoral advantage.9,25,26 In the early 1900s, Walter Laidlaw (1861–?), director of the Population Research Bureau of the New York Federation of Churches, found that these politically driven temporal shifts in ward boundaries made it difficult to track and predict congregation size and composition over time.25,26 In 1906, he argued for the creation of small permanent units of geography, whose boundaries would not be affected by political manipulation,69 and his case convinced the chief of the Division of Population at the Census Bureau.25,26,70 In 1910, for the first time ever, the US Census created small geographic units for eight large cities, including New York City.25,26,70

Immediately bringing public health into the mix, in 1910 the New York City Department of Health promptly used these new units of local geography—which they termed “sanitary areas”—to improve public health data and programs.25,26,70 Enthusiasm for “sanitary areas” spread to other cities, and in 1924 the US Census Bureau created a Cities Census Committee to expand their use.25,26 A key proponent of this effort was Howard Whipple Green (1893–1959), a statistician based in Cleveland, Ohio, who was keenly aware of these area’s public health value.25,26 In 1927 he succeeded in getting “sanitary areas” demarcated in Cleveland, and his work led to 30 US cities having these areas defined for the 1930 Census.25,26 However, in response to rising use of these area data by nonhealth agencies and researchers (including by businesses seeking to describe their market populations), the census changed the name from “sanitary areas” to “census tracts,” a term employed to this day.25,26,63

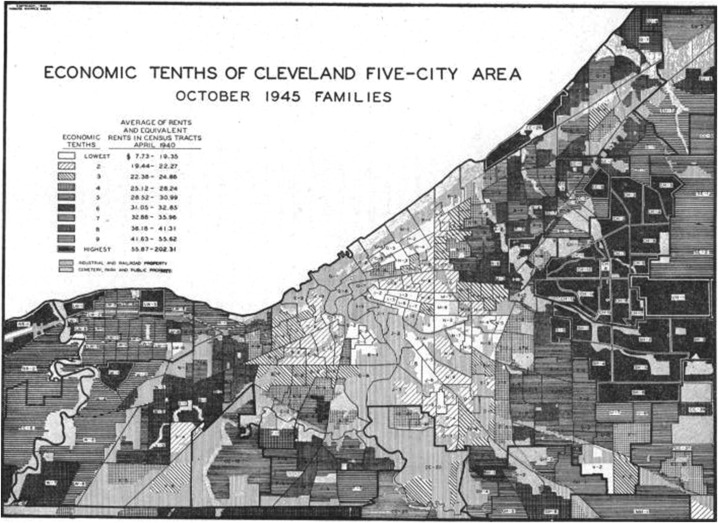

In 1931, Green became the chair of the Committee of Census Enumeration Areas in the American Statistical Association,25,26 whose work led to the permanent use of census tracts by the US Census; in the 1940 Census, 64 cities had census tracts, over twice the number in the 1930 census.25,26 During this same period, Green produced a series of studies describing the distribution, by census tracts, of economic conditions and diverse health outcomes, including tuberculosis and infant mortality.71–73 Other researchers followed suit, with studies linking census tract economic conditions to tuberculosis74,75 and all-cause mortality.76 In 1947, Green wrote a summary article on the use of census tracts to analyze city health problems.77 Figure 4 shows the map he included of the 1940 economic distribution of Cleveland’s census tracts (categorized by decile of “rent of tenant-occupied homes and rent equivalent of owner-occupied homes”) and the adverse socioeconomic gradient they revealed for White infant mortality.77 By the early 1950s, the utility of census tracts for vital statistics and urban planning was definitively established, and the US Census appointed local liaisons to establish census tracts nationally.4,5,25,26,70,78 Laidlaw and Whipple’s vision was finally realized in the 2000 Census, when all US counties included census tract subdivisions.26

FIGURE 4—

1940 Census Tracts and Economic Gradients in the White Infant Mortality Rate, Cleveland, OH

Note. Economic tenths defined in relation to “rent of tenant occupied homes and rent-equivalent of owner-occupied homes.”

Source. Green.77 Reprinted with permission.

Census tract data continue to be used extensively in US public health monitoring and research.25,79 Work I have led since the early 1990s, for example, has empirically demonstrated the validity and utility of using census tract poverty data to monitor and analyze health inequities80,81; our newer work reveals associations between census tract measures of racialized economic segregation and adverse health outcomes.82.83 Continued advances in geographic information systems and science ensure that linkage of census tract and other area-based census data to health and other outcomes will continue to play a vital role in documenting and monitoring links between the areas in which people live and work, their political representation, and their health and well-being—and the implications for social justice and health equity.79

CENSUS POLITICS AND THE PEOPLE’S HEALTH

As these three examples reveal, the US Census and public health are interdependent; a corollary is that inadequate census data—and insufficient funding for the US Census—are threats to the nation’s health and to health equity. US Census data have always been and will continue to be a political instrument, one that will be used—and potentially abused—to distribute political power and resources,1,2 thereby affecting people’s well-being and health inequities. As I prepare this article, one such prominent example involves the Trump administration’s effort to add questions about citizenship to the 2020 Census84; a legal challenge to this proposal is under way, precisely because evidence indicates it would increase the undercount of immigrants, including undocumented persons, and their families and communities.85–89 The Trump administration has also sought to block inclusion of validated questions about Arab Americans90 and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons91,92—as well as entirely erase the category of transgender93,94—steps that are inimical to understanding and quantifying the social conditions and health of these populations.90–96

Such distortions of census data are harmful, including to the people’s health. The only way to oppose such invidious efforts is to do so loudly, with evidence, calling backlash what it is—an attack on rights gained—and with a clear vision of a more equitable world.97–99 Public health has long since earned its place at the table over decisions about the scope and use of US Census data. As part of the values and vision for governance that produces and uses census data, the stance of public health should be to insist on securing the data and resources, including for the US Census, that provide the factual evidence needed for good governance and the ongoing struggle for health equity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work on this article was in part supported by the American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor Award (to N. Krieger).

I would like to thank Elizabeth Fee (1947–2018) for inviting me to write this article, which I dedicate to her memory.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson MJ. The American Census: A Social History. 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schor P. Counting Americans; How the US Census Classified the Nation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thorvaldsen G. Censuses and Census Takers: A Global History. London, UK: Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker PC. Uses of the census and ACS: federal agencies. In: Anderson MJ, Citro CF, Salvo JJ, editors. Encyclopedia of the US Census: From the Constitution to the American Community Survey. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press; 2012. pp. 384–385. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaines LM, Gage L, Salvo JJ. Use of the census and ACS: state and local governments. In: Anderson MJ, Citro CF, Salvo JJ, editors. Encyclopedia of the US Census: From the Constitution to the American Community Survey. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press; 2012. pp. 386–388. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hetzel AM. History and Organization of the Vital Statistics System. In: Vital Statistics of the United States, vol 1, 1950, pp. 1–19. Reprinted in: US Vital Statistics System, Major Activities and Developments, 1950–95. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1997.

- 7. Rothwell CJ; with contributions by Dorothy S. Harshbarger. Vital registration and vital statistics. In: Anderson MJ, Citro CF, Salvo JJ, eds. Encyclopedia of the US Census: From the Constitution to the American Community Survey. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press; 2012:395–398.

- 8.Friedman DJ, Hunter EL, Parrish RG II, editors. Health Statistics: Shaping Policy and Practice to Improve the Population’s Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bulmer M. History of social survey. In: Smelser NJ, Baltes PB, editors. International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2001. pp. 14469–14473. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Detels R, Beaglehole R, Lansang MA, Gulliford M, editors. Oxford Textbook of Public Health. 5th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Detels R, Gulliford M, Karim QA, Tan CC, editors. Oxford Textbook of Global Public Health. 6th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider M-J. Introduction to Public Health. 5th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldsteen RL, Goldsteen K, Graham D. Introduction to Public Health. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Somerville M, Kumaran K, Anderson R. Public Health and Epidemiology at a Glance. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothman K. Epidemiology: An Introduction. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keyes KM, Galea S. Population Health Science. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krieger N. Epidemiology and the People’s Health: Theory and Context. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen PC. A Calculating People: The Spread of Numeracy in Early America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deutsch A. The first US census of the insane (1840) and its use as pro-slavery propaganda. Bull Hist Med. 1944;15(5):469–482. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krieger N. Shades of difference: theoretical underpinning of the medical controversy on black/white differences in the United States, 1830–1870. Int J Health Serv. 1987;17(2):259–278. doi: 10.2190/DBY6-VDQ8-HME8-ME3R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snipp CM. American Indians and Alaska Natives. In: Anderson MJ, Citro CF, Salvo JJ, editors. Encyclopedia of the US Census: From the Constitution to the American Community Survey. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press; 2012. pp. 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liebler C. Counting America’s First Peoples. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2018;677(1):180–190. doi: 10.1177/0002716218766276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jobe MM. Native Americans and the US Census: a brief historical survey. J Gov Inf. 2004;30(1):66–80. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haozous EA, Strickland CJ, Palacios JF, Arambula Solomon TG. Blood politics, ethnic identity, and racial misclassification among American Indians and Alaska Natives. J Environ Public Health. 2014;2014:321604. doi: 10.1155/2014/321604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieger N. A century of census tracts: health & the body politic (1906–2006) J Urban Health. 2006;83(3):355–361. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9040-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salvo JJ. Census tracts. In: Anderson MJ, Citro CF, Salvo JJ, editors. Encyclopedia of the US Census: From the Constitution to the American Community Survey. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press; 2012. pp. 82–84. [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Constitution of the United States: a transcription. US National Archives. Available at: https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution-transcript. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 28.Heelen JP. revised by Margo J. Anderson. Census law. In: Anderson MJ, Citro CF, Salvo JJ, editors. Encyclopedia of The US Census: From the Constitution to the American Community Survey. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press; 2012. pp. 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mintz S. Winning the vote: a history of voting rights. Hist Now (Christch). 2004. Available at: https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-now/winning-vote-history-voting-rights. Accessed August 3, 2018.

- 30.Blumin SM. Making (white male) democracy: suffrage expansion in the United States from the Revolution to the Civil War. Hist Now (Christch). 2018. Available at: https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-now/making-white-male-democracy. Accessed August 4, 2018.

- 31.Dunbar Ortiz R. An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson M. Three-Fifths Compromise. In: Anderson MJ, Citro CF, Salvo JJ, editors. Encyclopedia of the US Census: From the Constitution to the American Community Survey. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press; 2012. pp. 379–380. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krieger N. Discrimination and health inequities. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour M, editors. Social Epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 63–125. [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2017. 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/index.htm. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 35.Faust DG, editor. The Ideology of Slavery: Proslavery Thought in the Antebellum South, 1830–1860. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen PC. Decennial Censuses: 1840 Census. In: Anderson MJ, Citro CF, Salvo JJ, editors. Encyclopedia of the US Census: From the Constitution to the American Community Survey. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press; 2012. pp. 132–133. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Measuring America: The Decennial Censuses from 1790 to 2000. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shattuck L. Report to the Committee of the City Council Appointed to Obtain the Census of Boston for the Year 1845. Boston, MA: J. H. Eastburn; 1846. [reprinted: New York, NY: Arno Press; 1976] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chadwick E. Report to Her Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for the Home Department, From the Poor Law Commissioners on an Inquiry Into the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain: With Appendices. London, UK: W. Clowe & Sons, for HMSO; 1842. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rosen G. A History of Public Health. (1958) Revised expanded edition; Foreword by Pascal James Imperato; Introduction by Elizabeth Fee; biographical essay and new bibliography by Edward T. Morman. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2015.

- 41.Porter D. Health, Civilization, and the State: A History of Public Health From Ancient to Modern Times. London, UK: Routledge; 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shattuck L, Banks NP, Jr, Abbott J. Report of A General Plan for the Promotion of Public and Personal Health, Devised, Prepared and Recommended by the Commissioners Appointed Under a Resolve of the Legislature of Massachusetts, Relating to a Sanitary Survey of the State. Presented April 25, 1850. Boston, MA: Dutton & Wentworth; 1850. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenkrantz B. Public Health and the State: Changing Views in Massachusetts, 1842–1936. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krieger N. Counting accountably: implications of new approaches to classifying race/ethnicity in the 2000 census. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(11):1687–1689. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.11.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tallbear K. Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pascoe P. What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47.US Census Bureau. American fact finder. Detailed race, total population, 2012–2016 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. Available at: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_16_5YR_C02003&prodType=table. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 48.Burhansstipanov L, Satter DE. Office of Management and Budget racial categories and implications for American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(11):1720–1723. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.11.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Arias E, Heron M, National Center for Health Statistics, Hakes J, US Census Bureau. The validity of race and Hispanic-origin reporting on death certificates in the United States: an update. Vital Health Stat 2. 2016;(172):1–21. [PubMed]

- 50.Jim MA, Arias E, Seneca DS et al. Racial misclassification of American Indians and Alaska Natives by Indian Health Service Contract Health Service Delivery Area. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 3):S295–S302. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liebler CA, Porter SR, Fernandez LE, Noon JM, Ennis SR. America’s churning races: race and ethnic response changes between Census 2000 and the 2010 Census. Demography. 2017;54(1):259–284. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0544-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anderson RN, Copeland G, Hayes JM. Linkages to improve mortality data for American Indians and Alaska Natives: a new model for death reporting? Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 3):S258–S262. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris R, Nelson LA, Muller C, Buchwald D. Stroke in American Indians and Alaska Natives: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):e16–e26. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Joshi S, Weiser T, Warren-Means V. Drug, opioid-involved, and heroin-involved overdose deaths among American Indians and Alaska Natives—Washington, 1999–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(50):1384–1387. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6750a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoopes M, Dankovchik J, Weiser T et al. Uncovering a missing demographic in trauma registries: epidemiology of trauma among American Indians and Alaska Natives in Washington State. Inj Prev. 2015;21(5):335–343. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2014-041419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bigback KM, Hoopes M, Dankovchik J et al. Using record linkage to improve data quality for American Indian and Alaska Natives in two Pacific Northwest state hospital discharge databases. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(suppl 1):1390–1402. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Dyke ER, Blacksher E, Echo-Hawk AL, Bassett D, Harris RM, Buchwald DS. Health disparities research among small tribal populations: describing appropriate criteria for aggregating tribal health dat. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184(1):1–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sarfati D, Garvey G, Robson B et al. Measuring cancer in indigenous populations. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(5):335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.NCAI Policy Research Center. The state of tribal data capacity in Indian Country: key findings from the Survey of Tribal Data Practices. National Congress of American Indians, October 2018. Available at: http://www.ncai.org/policy-research-center/research-data/prc-publications/Tribal_Data_Capacity_Survey_FINAL_10_2018.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 60.US Census Bureau. 2020 Census tribal consultations with federally recognized tribes: final report. September 2017. Available at: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2017/dec/2020-federally-recognized-tribes.html. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 61.US Census Bureau. Buffalo Dance—Allan Houser (1914–1994). Census 2000: US Census marketing posters. Available at: https://www.census.gov/dmd/www/houser.htm. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 62.US Census Bureau. The 2020 Census at a Glance. September 20, 2018. Available at: https://www.census.gov/library/fact-sheets/2019/dec/2020-at-a-glance.html. Accessed May 2, 2019.

- 63.US Census Bureau. 2010 geographic terms and concepts—census tract. Last revised December 6, 2012. Available at: https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/gtc/gtc_ct.html. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 64.Residents of Hull House. Hull-House Maps and Papers: A Presentation of Nationalities and Wages in a Congested District of Chicago: Together With Comments and Essays on Problems Growing Out of the Social Conditions. Attribution by Residents of Hull-House, a Social Settlement at 335 South Halsted Street, Chicago, Ill. New York, NY: T. Y. Crowell; 1895. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Deegan MJ. WEB Du Bois and the women of Hull-House, 1859–1899. Am Sociol. 1988;19(4):301–311. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Du Bois WEB. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania; 1899. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Green A. WEB Du Bois’ hand-drawn infographics of African-American life (1900). The Public Domain Review, 2017. Available at: https://publicdomainreview.org/collections/w-e-b-du-bois-hand-drawn-infographics-of-african-american-life-1900. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 68.Du Bois WEB. Mortality among American Negroes. Chart prepared by Du Bois for the Negro Exhibit of the American Section at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900. Library of Congress Prints and Photograph Division, Lot 11931, no. 59 (M) [P&P]. Available at: https://loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.33921. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 69.Laidlaw W. Federation districts and a suggestion for a convenient and scientific city map system. Federation. 1906;IV:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watkins RJ. Introduction. In: Watkins RJ, Swift AL Jr, Green HW, Eckler AR, editors. Golden Anniversary of Census Tracts. Washington, DC: American Statistical Association; 1956. pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Green HW. Tuberculosis and Economic Strata, Cleveland’s Five-City Area, 1928–1931. Cleveland, OH: Anti-Tuberculosis League; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Green HW. The use of census tracts in analyzing the population of a metropolitan community. J Am Stat Assoc. 1933;28(181A):147–153. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Green HW. Infant Mortality and Economic Status: Cleveland Five-City Area. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Health Council; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nathan WB. Health Conditions in North Harlem 1923–1927. New York, NY: National Tuberculosis Association; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Terris M. Relation of economic status to tuberculosis mortality by age and sex. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1948;38(8):1061–1070. doi: 10.2105/ajph.38.8.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sheps C, Watkins JH. Mortality in the socio-economic districts of New Haven. Yale J Biol Med. 1947;20(1):51–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Green HW. Use of census tracts in the analysis of city health problems. Am J Public Health. 1947;37(5):538–542. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Coulter EJ, Guralnick L. Analysis of vital statistics by census tract. J Am Stat Assoc. 1959;54(288):730–740. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Krieger N. Follow the North Star: why space, place, and power matter for geospatial approaches to cancer control and health equity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(4):476–479. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(5):703–710. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramanian SV. Painting a truer picture of US socioeconomic and racial/ethnic health inequalities: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):312–323. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.032482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Krieger N, Waterman PD, Spasojevic J, Li W, Maduro G, Van Wye G. Public health monitoring of privilege and deprivation with the Index of Concentration at the Extremes. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):256–263. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Krieger N, Kim R, Feldman J, Waterman PD. Using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes at multiple geographical levels to monitor health inequities in an era of growing spatial social polarization: Massachusetts, USA (2010–14) Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):788–819. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.US Census. Census Bureau submits planned questions for 2020 Census to Congress. US Census Bureau press release no. CB18-55, March 29, 2018. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/2020-question.html. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 85.Wines M, Baumgartner E. At least twelve states to sue Trump administration over census citizenship question. New York Times, March 27, 2018. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/27/us/census-citizenship-question.html. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 86.Liptak A. Supreme Court allows trial on census citizenship to go forward. New York Times, November 2, 2018. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/02/us/politics/supreme-court-census-citizenship-question.html. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 87.Brown N. Citizenship question could hamper US Census response: official. US News and World Report, November 2, 2018. Available at: https://www.usnews.com/news/top-news/articles/2018-11-02/citizenship-question-could-hamper-us-census-response-official. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 88.Gunter C. As trial looms, survey shows citizenship question could harm 2020 census. FCW: The Business of Federal Technology, November 2, 2018. Available at: https://fcw.com/articles/2018/11/02/census-survey-lawsuit-gunter.aspx. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 89.Wines M. Inside the Trump administration’s fight to add a citizen question to the census. New York Times, November 4, 2018. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/04/us/wilbur-ross-commerce-secretary.html. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 90.Lowry M. Statement: AAI responds to rejection of “the Middle Eastern or North African” category from the 2020 Census. Arab American Institute, January 26, 2018. Available at: http://www.aaiusa.org/statement_aai_responds_to_rejection_of_the_middle_eastern_or_north_african_category_from_the_2020_census. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 91.O’Hara ME. LGBTQ Americans won’t be counted in 2020 US Census after all. NBC News, March 29, 2017. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/lgbtq-americans-won-t-be-counted-2020-u-s-census-n739911. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 92.Morabia A. Note from the editor-in-chief: who wants to exclude older LGBT persons from public health surveillance? Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):844–845. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Green EL, Benner K, Pear R. “Transgender” could be defined out of existence under Trump administration. New York Times, October 21, 2018. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/21/us/politics/transgender-trump-administration-sex-definition.html?module=inline. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 94.Mervosh S, Hauser C. At rallies and online, transgender people say they #WontBeErased. New York Times, October 22, 2018. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/22/us/transgender-reaction-rally.html. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- 95.Kayyali R. US Census classifications and Arab Americans: contestations and definitions of identity markers. J Ethn Migr Stud. 2013;39(8):1299–1318. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sell RL. LGBTQ health surveillance: data = power. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):843–844. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Klein N. No Is Not Enough: Resisting Trump’s Shock Politics and Winning the World We Need. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Solnit R. Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities. 3rd ed. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Greenblatt S. Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics. New York, NY: WW Norton & Co; 2018. [Google Scholar]