INTRODUCTION

This article examines the communities in which Spanish-speaking children of immigrants are growing up and the opportunities these communities offer for the acquisition of English, maintenance of Spanish, and the development of literacy skills in both language. Ultimately, these opportunities will influence children’s integration into U.S. society and their ability to maintain the language and culture of their families. The tension between social integration and linguistic and cultural maintenance is palpable. The massive “Day Without Immigrants” demonstrations on May 1, 2006, urging Congress to enact legislation designed to facilitate the legal incorporation of undocumented immigrants into the workforce and ultimately into American society (Gorman, Miller, & Landsberg, 2006), brought to the forefront debate about the nature of the United States as a pluralistic and multicultural nation of immigrants. Newspapers carried stories focusing on the impact of immigration on local communities and expressing considerable concern about the incorporation of present-day immigrants into the American social fabric. In particular, there was concern that contemporary immigrants, mainly from Latin America and Asia, are not learning English, and thus not assimilating into American society, as quickly as immigrants in the past (McKay & Wong, 2000). How these children fare in school and work will affect them, their families, and the society as a whole.

Spanish-speakers are by far the largest language-minority group in the U.S., comprising more than 10% of the total U.S. population and 60% of the language minority population (Shin & Bruno, 2003). The focus of our analysis is on the relationship between Spanish-speaking children’s out-of-school literacy-learning opportunities (community and home) and their early literacy achievement in both English and Spanish. We look at ways in which the language characteristics of the communities where Spanish-speaking children live might influence patterns of home language and literacy use, which in turn influence early literacy achievement in English and Spanish. We pay particular attention to access to oral and written language in the children’s first language (L1) and second language (L2) in different types of communities.

For immigrants and children of immigrants, full and equitable incorporation into American society involves at least moderately high levels of English language proficiency and literacy attainment. These accomplishments, in turn, require access to quality schooling and learning opportunities outside of school. As a group, children from non English speaking homes tend to lag behind their mainstream peers on both state (e.g., California Department of Education, 2005) and national (e.g., Institute of Education Sciences, 2005) tests of academic achievement. Yet, as might be expected, there is a considerable range of outcomes among these children. On the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), for example, most English learners score below basic. However, 27% score at or above basic and 7% score at or above proficient (Institute of Education Sciences, 2005). Clearly, some English learners do very well in school and beyond, while others lag far behind. What explains this variability, and can understanding its sources help us understand how to improve learning outcomes for more children from Spanish-speaking homes?

FAMILY AND COMMUNITY INFLUENCES ON LITERACY DEVELOPMENT

Family practices associated with children’s literacy development have been widely studied over the past 25 years. In general, greater amounts of literacy and oral language in the home are associated with higher levels of children’s language and literacy development (Booth & Dunn, 1996; Hart & Risley, 1995. However, for the nearly 10 million children in the United States who come from homes where a language other than English is spoken--70% of whom are Spanish speakers--the dynamics of language and literacy use in the home and literacy attainment at school are necessarily more complex than are those for monolingual speakers of English. These children experience literacy at home in a language other than the one that ultimately they must master in order to succeed in school and beyond. Moreover, even in homes where a language other than English is used, there is generally at least some level of English use as well.

How children growing up in multilingual communities acquire and develop literacy in one, two, or several languages have received increasing scholarly attention over the past two decades (Bayley & Schecter, 2003; Martin-Jones & Jones, 2000; McCarty, 2005). Families’ literacy practices include both the activities involving use of text themselves, but also the cultural values, attitudes, feelings and relationships that shape and give meaning to those activities (Barton & Hamilton, 2000; Street, 1993). With respect to immigrant Latino families, studies have documented ways in which parents’ cultural experiences guide literacy practices with their children. For example, Valdés (1996) noted that Mexican immigrant parents of kindergartners did not anticipate that the school expected children to know their ABC’s by the time they began first grade, since in Mexico ability to recite the alphabet is not considered particularly important Findings from a longitudinal study of second generation Latino students in the greater Los Angeles area indicated that families’ home country experiences, including grandparents’ level of education and parents’ experience growing up in a rural vs. an urban community, continued to influence children’s literacy development as late as middle school (Reese, Garnier, Gallimore, & Goldenberg, 2000). Home country experiences of these Latino immigrant parents also served to shape the ways in which they engaged in oral reading with their children, including their motivations for reading and their understandings, or cultural models, of the nature of literacy itself. However, these cultural models were not static; rather, they changed over time as families adapted to U.S. environments and school demands (Reese & Gallimore, 2000).

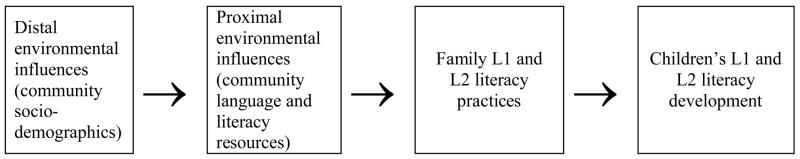

Ecocultural theory (Gallimore et al. 1989; Reese, Kroesen, & Gallimore, 2000; Weisner 1984; Whiting & Whiting, 1975) provides a useful orientation for analyzing family practices within and across contrasting settings, taking into account cultural influences on family practices. This approach focuses on the everyday routines constructed and sustained by families. A family’s routine is seen as a compromise between the structural and ecological constraints that families must live with on one hand, and the cultural values, understandings, models and beliefs which guide and give meaning to people’s lives. Thus, ecocultural analyses encompass both the structural and the cultural forces shaping daily life and influencing decisions and accommodations made by individuals and families (Gallimore, Goldenberg & Weisner 1993). An important feature of this perspective is that distal environmental influences such as the socioeconomic status or ethnic homogeneity of the community are conceptualized as exerting an indirect influence on children’s developmental outcomes by influencing the more proximal environment with which children and families are engaged. With respect to literacy development, ecocultural theory predicts that family literacy practices will influence children’s literacy development and will be shaped and/or constrained by proximal environmental factors such as the availability of literacy resources in L1 and/or L2 in the community where families live.

Recent literacy research has documented literacy practices in a wide variety of communities and out-of-school settings, emphasizing the notion of “literacies”, that is, that there are different literacies associated with different domains of life (Barton & Hamilton, 1998; Barton, Hamilton & Ivanic, 2000; Moss, 1994; Street; 1993). In a study of the uses of written language among immigrant families in Chicago, Farr (1994) described literacy practices in terms of the domains in which these literacy acts occurred, identifying the five domains of religion, commerce, politics/law, family/home, and education. Participation in community literacy practices can fulfill a variety of purposes including reinforcement of ethnic pride and identity (Pak, 2003), participation in religious services and observations (Reese, Linan Thompson, & Goldenberg, 2005), or navigation of demands by government agencies such as the IRS or INS (Farr, 1994). It is likely, then, that children’s engagement in activities making use of text material in one or both languages may influence their literacy development in general and in the long term. However, in “nonmainstream communities…literacy practices might--or more likely--might not match literacy practices in mainstream academic communities” (Moss, 1994, p. 2). Therefore, the extent to which community literacy resources contribute to specific academic outcomes is not a given and has yet to be documented.

The present study addresses this issue through the following questions regarding communities with large populations of Spanish-speaking children and families:

What is the relationship between community socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., income, educational level, and ethnic heterogeneity) and the language and literacy resources that exist in the community?

What is the relationship between community language and literacy resources and family literacy practices in English and Spanish?

What is the relationship between family literacy practices in English and Spanish and children’s early reading achievement in English and Spanish?

Ultimately the question we are addressing is to what extent community socio-demographics (distal influences on family literacy practices) and community language and literacy resources and opportunities (proximal influences) facilitate or constrain family literacy practices, which then predict child literacy outcomes.

METHODS

This study is part of larger longitudinal study of language and literacy development among Spanish-speaking children carried out in 35 schools and communities in California and Texas. The Oracy/Literacy study developed a common set of data collection protocols for examining literacy development in English and Spanish, classroom instruction, family practices, and community characteristics. The present study focused on literacy development outside of school. Measures include individual assessments of children’s early literacy and oral language proficiencies in English and Spanish, neighborhood observational surveys, parent surveys, and principal, parent and child interviews, and teacher focus group interviews.

Sample Selection

We selected a total of 35 schools in urban California (12) and urban and border Texas (12 and 11, respectively). Schools were selected in order to maximize variability with respect to school program and community characteristics. Yet we had to select schools with substantial Latino/ELL populations so that there would be sufficient children at each school (approx. 40 Spanish speaking ELLs/school in kindergarten) to permit meaningful inferences for schools and communities. (Since this was to be a longitudinal sample, we also had to take attrition into account.) Therefore, selection criteria required that schools have at least 40% Latino enrollment overall and at least 30% English language learner (ELL) enrollment in grades K and 1. These minimum percentages provided assurance of a sufficiently large Spanish-speaking population at the school and in the community. Sixty percent of ELLs in California and Texas attend schools that have greater than 30% ELL enrollment (August & Shanahan, 2006), so our sample schools were well within the typical range of ELL concentration in the two states where the study was conducted.

We furthermore sampled schools from a range of language programs for ELLs: English immersion, transitional bilingual education, developmental (or maintenance) bilingual education, and dual-language bilingual education (see Genessee, 1999, for more information on each of these program models). Finally, we sampled schools in diverse community types: ethnically heterogeneous, ethnically homogeneous (i.e. almost exclusively Latino), mixed income and low income communities.

Because we wanted to study at least adequate exemplars within each of these program categories, schools were rank ordered by achievement (Academic Performance Index, or API, in California; Texas Education Agency, TEA, ratings in Texas), within program (English immersion, etc.) and geographic site (urban and border Texas; urban California). In one case, we recruited a California school that had a relatively low API score but that had high scores in Spanish reading in grades 2–5 (64th-67th national percentile on the Spanish Assessment of Basic Skills; CTB-McGraw Hill).

Data Collection

Parent survey

Parents were surveyed using a written questionnaire sent home through the child’s classroom teacher. This protocol included questions in Spanish on family sociodemographics (occupation, length of time in the local community, education), parents’ expectations regarding their children’s academic attainment and performance, school-related interactions, reported home literacy and homework practices, and the child’s behavioral adjustment. Of the 1865 parents we attempted to survey, 1418 (76%) returned the surveys with at least some responses. Numbers are lower for the analyses due to missing data.

Parent interviews with key informant families

A subset of families at each school were selected to be interviewed in greater depth, participating in three home interviews over the course of the school year. Children’s academic performance was rated by the teacher as high, medium, or low. For each school or program, four families were randomly selected for participation—one from the high group, two from the medium group, and one from the low group. Each interview lasted approximately 90–120 minutes. Most interviewees were the children’s mothers; however, one family was headed by a single father, and fathers participated in some of the other interviews with the mothers. Project-trained interviewers were bilingual; most were themselves first- or second-generation Latino immigrants. The interviews focused on family language and literacy practices, attitudes, and materials. Also included was information on how long parents had lived in the local community, their perceptions about community resources and safety, and their participation in church and other community organizations. Parents were also asked about their own schooling experiences in their home countries, their school and job-related experiences in the United States, and ways in which they believed that their experiences might influence their children. Detailed data about the children’s daily activities outside school, on both weekends and weekdays, and the opportunities for children’s participation in literacy activities of different types in the community were collected, as well as parents’ perceptions of neighborhood patterns of language and literacy use and potential barriers to children’s literacy development and academic progress.

School attendance area surveys (SAAS & SAAS-L)

We surveyed the school attendance neighborhood to assess languages heard and observed in different neighborhood settings. We also collected data on the types and condition of dwellings, the types and density of commercial enterprises, the presence and condition of recreational facilities such as parks and swimming pools, and the presence of organizations (such as sports clubs) and institutions (such as churches, libraries, health facilities etc.). Project investigators drove or walked each street in the neighborhood and stopped to observe key areas such as parks, grocery stores, libraries, and recreation centers (as available). Samples of free materials were collected. Observational data were recorded in two ways: on precoded forms and in relatively open-ended (but structured according to a common format) field notes where we made extensive notes on the characteristics described above. Field notes and coded survey protocols were augmented by photos and video footage taken to facilitate coding and write-up. Each survey took approximately 8 hours in the field, followed by approximately 10 hours of coding and field note write up.

Following completion of the SAAS and identification of key locales in which literacy materials were most likely to be available (e.g. markets, bookstores, libraries, community centers), a second survey focusing on literacy (SAAS-L) was carried out. In this survey, language use by participants in the setting was noted and textual materials (books, magazines, fliers, newspapers, greeting cards, and environmental print such as signs and notices) were coded for quantity, language, and type.

Principal interview and survey

Each school principal was interviewed for approximately 2 hours about characteristics of school functioning and culture that might influence students’ achievement. Specifically, principals were asked to describe the community in which the school was located, the families and children who attended the school, changes in the community and school over time, learning resources available or lacking in the local area, and school attempts to involve parents and the community. Principals also filled out a detailed survey about student performance and a variety of factors that may be associated with performance: family and staff demographic profiles, class size, policies involved in academic tracking and retention in grade, scheduling, available resources, and so on.

Teacher focus group interview

A focus group interview of approximately 2 hours in length was carried out with 5–8 teachers from each school site. The teachers were chosen by the principals to represent a range of grade levels, number of years of experience in the teaching profession, and, where applicable, to include both bilingual and monolingual teachers. The teacher focus group protocol included the same questions and topics as those discussed with the principals.

U.S. census

U.S. Census data from 2000 were also gathered to provide background demographics such as ethnic distribution, home ownership, family size, and so on for the census tract in which each school attendance area was located.

Student achievement

Trained research assistants administered the Woodcock Language Proficiency Battery-Revised in English and Spanish (Woodcock, 1991; Woodcock & Muñoz-Sandoval, 1995). The WLPB-R is perhaps the most widely used assessment of language and literacy achievement in the United States. It has parallel forms in English and Spanish, thereby permitting comparisons of achievement within and across languages. We report scores on first grade basic reading (decoding and word recognition) and passage comprehension.

Family Sample Description

The total sample included 1418 students selected at random from classrooms at the school with at least 50% Spanish-speaking ELLs. A large majority of parents were immigrants from Latin America, with 76% of mothers (female head of household) and 75% of fathers (male head of household) from Mexico. Seventeen percent (17%) and 18% of mothers and fathers, respectively, were born in the US. Mothers averaged 11.4 years and fathers averaged 13.9 years in the U.S. The mean number of years of schooling parents received was 9.1.

ANALYSIS

The analyses reported here represent a first step in trying to understand the complex relationships between family and community factors on the one hand and Spanish-speaking children’s early reading attainment on the other. Although many possible analytical strategies are available (e.g., regression, structural equation modeling) and other variables could be included in analyses (e.g., family demographics), at this initial stage we use simple correlations to explore bivariate relationships that exist among community socio-demographics, community language and literacy resources, and family literacy practices in English and Spanish. We also examine the relationship between family literacy practices and children’s first grade reading achievement in English and Spanish. Our goal in this paper is to report plausible, empirically-grounded hypotheses that future analyses will confirm or reject.

The data exist at two levels: Community and family (including child level test data). Correlations involving community-level variables were calculated at the community level with all 35 communities. Interpretation of these correlations is straightforward--the degree of association between pairs of variables characterizing the communities in the study (e.g., mean income level and language heard in the community). We report correlations that reached the standard .05 level of significance.

Correlations involving family and child variables were calculated at the family/child level; their interpretation is also straightforward--the degree of association between family literacy practices (e.g., language in which parents read) and children’s reading achievement (e.g., passage comprehension in Spanish). Because of our very large sample, many weak correlations (below .10) were statistically significant at beyond the .001 level. In order to prevent interpreting trivial associations (less than 1% of explained variance), we set the threshold for reporting correlations at the family/child level at .15, indicating a bivariate relationship in which one variable accounts for more than 2% of the variance in the other.

Analyses that involved both community level (e.g., percent of English only speakers in the census tract) and family level (e.g., frequency of parents’ reading) variables present more of a challenge, since interpretation of the correlations is less straightforward. We must be particularly mindful of the “ecological fallacy” (Sirin, 2005), that is, making individual-level inferences from group-level data. Group-level and individual-level analyses address subtly different questions, even when they use the same variables. We therefore calculated the correlations involving community and family level variables in two ways:

At the community level, by aggregating family level data up, that is, averaging values of all families within the community and using the resulting average as a community-level value. These correlations involve an n of 35 cases. They tell us the degree of association between community characteristics and average values in the community on the family variables; but they tell us nothing about whether community variables are associated with individual family characteristics.

At the individual family level, by assigning to each family the community-level value that corresponds to the community-level variable. These correlations involve ns of approximately 1000, depending on missing family-level data. They tell us the degree to which community characteristics are associated with family-level characteristics. Although seemingly more meaningful intuitively, it is this type of analysis that is most prone to the “ecological fallacy,” since “an individual-level inference is made on the basis of group aggregated data” (Sirin, 2005, p. 419).

The general conceptual model underlying our analyses is depicted in Figure 1. A complete list of variables comprising each of the boxes in the conceptual model is provided in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of hypothesized relationships

Table 1.

Community and family variables used in the analysis

| Community socio-demographics | Community language and literacy resources | Family L1 and L2 literacy resources, practices | Children’s L1 and L2 literacy development |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

|

Language resources

|

Literacy practices

|

Basic reading

(Woodcock Language Proficiency Battery-Revised) |

We hypothesized that more distal features of the environment, such as concentrations of speakers of one language or another, would be associated with more proximal influences on children’s literacy development such as availability of text materials or the language of environmental print. The type, quantity, frequency and quality of the text materials in L1 and L2 in the surrounding community would then influence the frequency and types of literacy practices carried out in the home in ways that ultimately would influence the children’s literacy development (see Figure 1).

RESULTS

Community Characteristics and Language and Literacy Resource Availability

The communities are located in urban, suburban, and semi-rural settings in Southern California, border Texas, and in two centrally located Texas cities. Some neighborhoods are almost exclusively Latino where Spanish is the language heard. In other communities, Latinos occupy neighborhoods that include African American, White, Asian, and Pacific Islander populations as well. In some settings Spanish is heard but rarely seen in signage and printed materials available for sale, while in other settings Spanish print predominates. In some communities, families live in quiet, predominantly residential neighborhoods; other communities include shopping malls, small businesses, and public service locales such as community centers, municipal buildings, courthouses, and hospitals. Table 2 reports descriptive statistics for the community level variables used in this part of the analysis.

Table 2.

Community descriptive statistics

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community socio-demographic characteristics (distal) | |||||

| % Latino | 35 | 71.9 | 26.6 | 3.9 | 98.7 |

| % Latinos who are HS graduates | 35 | 39.4 | 17.0 | 12.33 | 91.5 |

| Commercial/residential heterogeneity | 35 | 2.9 | .7 | 2 | 4 |

| Median COL-adjusted income | 35 | $31,929 | $11,990 | $12,285 | $78,710 |

| Community literacy resources (proximal) | |||||

| Printed material for sale (excl. libraries, bookstores) | 35 | 65.9 | 94.0 | 0 | 432.5 |

| Number of books and magazines | 35 | 50,896 | 194,787 | 0 | 1,043,682 |

| # of libraries | 35 | .2 | .4 | 0 | 1 |

| # of bookstores | 35 | .4 | .8 | 0 | 3 |

| Community language of literacy resources (proximal) | |||||

| Lang of signs, newspapers, free printed material* | 35 | 3.6 | .8 | 1.6 | 5.0 |

| % of reading material for sale in Spanish | 35 | 12.9 | 21.9 | 0 | 100 |

| Lang of commercial signs* | 35 | 4.0 | .7 | 2 | 5 |

| Language of social services signs* | 35 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 1 | 5 |

| Community language resources (proximal) | |||||

| % population speaks only English | 35 | 30.3 | 24.1 | 3.0 | 91.4 |

| % population speaks Spanish; little or no English | 35 | 22.4 | 11.8 | 1.2 | 50.4 |

| Language heard around the community* | 34 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 1 | 5 |

| Language used in stores and other establishments* | 35 | 3.2 | 1.0 | 2 | 5 |

1=only Spanish, 2= mostly Spanish, 3=Spanish and English equally, 4=mostly English, 5=only English.

Table 3 summarizes the associations between community socio-demographic characteristics (distal influences) and language and literacy resources in the community (proximal influences) across the 35 communities. Community language and literacy resources, such as languages heard and seen, availability of books, and access to a library, vary according to community socio-demographics. The single most important variable among the community socio-demographic characteristics was per cent of the census tract that is Latino. Per cent Latino was correlated with 11 of the 12 language and literacy resources shown in Table 3. Communities with greater concentrations of Latino residents are less likely to have printed materials for sale, libraries, and bookstores. What materials are available have a greater likelihood of being in Spanish when a community has a higher concentration of Latinos. Finally, and not surprisingly, concentration of Latinos is associated with more use of Spanish in the community, among individuals, and inside stores and other establishments.

Table 3.

Relationship between community socio-demographic (distal) factors and literacy and language resources (proximal influences). All correlations significant at p≤.05.

| Community socio-demographics (distal environmental influences) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community literacy and language resources

(proximal environmental influences |

% Latino | % Latinos who are HS graduates | Residential/commercial heterogeneity | Median COL-adjusted income | |

| Literacy Resources | Printed material for sale

(excluding libraries, bookstores) |

−.34 | .53 | .37 | |

| Number of books and magazines | .41 | ||||

| # of libraries | −.49 | .36 | |||

| # of bookstores | −.47 | .45 | |||

| Language of literacy Materials | Language of signs,newspapers, free printed material* | −.59 | .59 | ||

| % of reading material for sale in Spanish | .42 | ||||

| Language of commercial signs* | −.48 | .49 | .38 | ||

| Language of social service signs* | −.53 | .36 | .48 | ||

| Community Language | % population speaks only English | −.96 | .54 | .54 | |

| % population speaks Spanish; little, no Eng | .76 | −.72 | −.42 | ||

| Language heard around the community* | −.78 | ||||

| Language used in stores and other establishments* | −.73 | .69 | |||

1=only Spanish, 2= mostly Spanish, 3=Spanish and English equally, 4=mostly English, 5=only English.

Higher income communities are more likely to have printed material for sale, but income level had no relationship with any other literacy indicators. Communities with a greater percentage of high school graduates among the Latino populace are also likely to have more literacy materials than communities with fewer high school graduates. Greater percentage of high school graduates is also associated with more materials in English and with more English use in the community. Communities with greater residential/commercial heterogeneity (i.e., greater percentage of commercial land use in comparison to residential) are more likely to have a greater number of books, magazines, libraries, and bookstores; English is also more likely to be heard in these communities.

Findings by Neuman & Celano (2001) and a three-case analysis by Smith, Constantino & Krashen (1997) that more literacy materials are available in higher SES neighborhoods are partly supported by our findings. The income level of the community and the educational level of the Latino population predict the amount of printed material for sale in the community, but they do not predict any other measure of quantity of print available such as number of books and magazines and number of libraries and bookstores. Higher educational attainment among the Latino community, however, was associated with more printed material in English. A contrastive case analysis carried out in a pilot year of work in two of our participating communities also indicated that availability of text material in Spanish did not follow the same pattern as that observed in English. More Spanish materials were available in the lower income, Latino neighborhood than in the higher income, predominantly Anglo and English-speaking neighborhood (Reese & Goldenberg, 2006). All three of the studies cited above are premised on the assumption that community availability of resources can/will play a role in children’s literacy development. Testing this assumption forms the basis for the questions posed in the sections to follow.

Community Language and Literacy Resources (proximal influences) & Family Literacy Practices

Are proximal community language and literacy resources associated with families’ literacy practices in English and Spanish? The answer varies by category of resource: Community literacy resources show very little relationship with family literacy practices. Community oral language characteristics, in contrast, show stronger relationships with family literacy practices, particularly family literacy practices analyzed at the community (rather than individual) level.

In this section we first report the absence of an association between community literacy and family literacy practices, followed by an illustrative case study of one of our communities that suggests an explanation for the absence of the predicted association. In the next section, we report on the one domain of proximal community resources--language use in the community--where we do see an association with family literacy practices, although in an unexpected direction.

Table 4 reports descriptive statistics for selected family level variables (at the family level).

Table 4.

Family literacy practices

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of reading to child in English** | 1314 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 0 | 4 |

| Frequency of reading to child in Spanish** | 1351 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 0 | 4 |

| Child reading language* | 893 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 1 | 5 |

| Parents’ reading language* | 1402 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 1 | 5 |

| # Adult books in the home | 1064 | 17.2 | 40.3 | 0 | 900 |

| # Child books in the home | 1287 | 30.0 | 46.2 | 0 | 700 |

| Frequency child reads on own** | 862 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 0 | 4 |

| Frequency Mother reads*** | 1384 | 2.8 | 1.2 | 0 | 4 |

| Frequency Father reads*** | 1288 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 0 | 4 |

1=only Spanish, 2= mostly Spanish, 3=Spanish and English equally, 4=mostly English, 5=only English.

0=almost never, 1= less than once a month, 2=1–2 times a month, 3=1–2 times a week, 4=daily

0=never, 1=less than once a month, 2=1–2 times a month, 3=1–2 times a week, 4=almost daily, 6=more than once a day

Community literacy resources and family literacy practices

At the family level, we found very few correlations between community literacy resources (identified in Table 2) and family literacy practices (shown in Table 4) high enough to meet our .15 threshold. Of the approximately 200 possible correlations, only 5 met the criterion: The number of books and magazines in the community was correlated with the frequency of reading to the child in English (.16) and the frequency that the child reads or looks at books in English on his or her own (.25). The number of bookstores was associated with the child’s reading or looking at books more in English (.18). The quality of Spanish literacy materials was associated (.21) with children’s reading or looking at books more in Spanish. One correlation was counterintuitive: The percentage of magazines in Spanish was associated (.19) with children reading more in English. Expected relationships, such as the number of books available in the community or presence of a library, on the one hand, and frequency of reading at home or books for children and adults at home, on the other, did not emerge.

When we did the analysis aggregated at the community level, we found only 4 significant correlations: language of commercial and social service signs each correlated (.37 and .32, respectively) with the average number (across project participants in the community) of children’s books in the homes. Total books available in the community predicted average frequency with which children were read to (.47); and the percentage of visited establishments that had free printed material predicted the frequency with which mothers report reading (.34).

Why do we find relatively little evidence for the effects of proximal community factors on home family literacy practices? Of course, it is possible that the ecocultural theory upon which the hypotheses were based is flawed (or only partially true), and, in fact, family practices operate relatively independently from the contexts in which families live. Or it might be that, although family practices are shaped by ecological and cultural factors, other processes might at work that diminish potential relationships between community influences and family practices. In the following section we will use one community case study to illustrate ways in which family agency works to counter structural influences reflected in the distal and proximal community factors described above.

Community Case Study of Family Use of Available Literacy Resources

The 35 communities included in our study include a wide range of characteristics—from urban to semi-rural, from exclusively Latino to predominantly Anglo and English-speaking, from exclusively residential neighborhoods to neighborhoods surrounded by strip malls, industrial parks, and shopping centers. While selection of a single representative community is close to impossible, the community surrounding Bell School, described below, is more or less typical of the Southern California communities in our study. It is mixed with regard to ethnicity and language, while the school program has switched to English immersion as a result of California legislation passed in 1998.

Community description

Bell Elementary School is located in the downtown area of a mid-sized coastal city in Southern California. The community is predominantly Latino and low income, but at the same time it is highly diverse with respect to ethnicity, language, SES and land use (residential/commercial/industrial). The neighborhood includes the civic center, with the city hall, court building, police department, and public library.

The major literacy resource in the community is the main library. A two-story building located in the civic center, it contains a large selection of books, magazines, and media materials in English and some materials in Spanish. Very little environmental print (such as signs, fliers) is in evidence in Spanish, or any language other than English. There are no bookstores in school attendance area neighborhood, but two are located close by; however, each of these contains very few books in Spanish. Few materials in the local discount grocery stores are available in either L1 or L2, but there is a Walmart close by with materials in English. Again, however, there are limited titles available in Spanish.

Survey data for the 40 participating families living in the Bell community indicated that all parents were native speakers of Spanish and were born outside of the U.S. Parents averaged 7.4 years of schooling. Mothers averaged 9.7 years in the U.S., and fathers slightly more (11 years). The great majority of families (92.5%) earned under $30,000/year, with 67% earning under $20,000/year.

Accessing “available” materials

Although materials may be available in what we have determined to be the “community” (School Attendance Area), they might not be equally accessible to all families. For example, three families described walking to the library because it was close; however, one family did not go because the children “no tienen credencial ellos para sacar [libros], se me ha hecho muy dificil para ellos” (‘they don’t have a credential [library card] to be able to take out [books], I have found it to be very difficult for them’). The school principal explained that one of the requirements for a library card was a social security number and that this was a problem for parents who were in the U.S. illegally.

Role of the school in providing materials for home use

At Bell School, all four interviewees took advantage of the school library to check out materials for their children, stating that reading materials not hard to obtain in their community because school provided them. One mother volunteered at school and checked out books: “Yo allí me voy de voluntaria y allí agarro el que yo quiero también” (‘I go there as a volunteer and there I take the books I want too’). Daily homework is a school policy, and many teachers send books home regularly. Another mother commented that her son “está estudiando los libros y haciendo lo que le dejan de tarea” (‘is studying the books and doing what they send as homework’). In addition, the school periodically gives away books that it no longer uses. “En la escuela también así les dan. De repente les dan su libro de los que ya no ocupan, que ya tienen de más, les dan que dos, que tres y así.” (‘At school they also give them out. At times they give them a book from those that they don’t need any more, since they have others, they give out two or three, like that’). The pattern of the school’s providing of take-home reading materials and books, through the school or classroom libraries, was found across schools in the study.

It may be that because schools included in our study were higher achieving schools, they were more proactive than normal in compensating for lack of availability of books in the community. One teacher described the role of the school as a service provider in the inner city neighborhood were it is located: “If they have any questions about, you know, police, or being evicted, or welfare, or social security, they come to school first even for help, even if they’re sick. They come to school to get the answers or get referred to somewhere, to some agency for some assistance; so, they really value our school being in this location.” It is possible that if there were a wider range in achievement levels represented in the schools participating in the study, we might also see greater variation in the extent to which the schools provided reading material to families. Regardless, in this sample of 35 schools we consistently heard reports of schools sending home homework and reading materials and making the school libraries available for parents and children to use. We suspect these actions by schools help mitigate the effect of low levels of literacy materials available in the community. Absent this school effect, we expect we would have seen a greater impact of availability of community literacy resources on children’s home literacy opportunities.

Accessing resources outside of the community

Although aspects of families’ daily routines may be constrained within the neighborhood by what is within walking distance, particularly low-income families with a single vehicle that is used by one of the parents to go to work, families can and do go outside of there immediate neighborhoods for a variety of purposes and activities. Church attendance is an example of an activity that takes some families outside of the neighborhood. Most families in the study report attending church; all four Bell families attend Catholic mass at St. Mark’s, about 10 blocks outside of their school attendance area neighborhood. As Catholics, the families do not attend one of the three Protestant churches located closer and within the neighborhood. At St. Mark’s, the church services are separated by language, which results in separation by ethnicity. “Hay misa para los Latinos y hay misa para los gabachos” (‘There is one mass for Latinos and one mass for white people’), and families in our study all attend the Spanish mass. Children also attend catechism classes on Saturdays in the church’s education building, with classes available in Spanish for the younger children and English for the older children. Some families report driving to neighboring communities on occasion to attend church with relatives. The church serves not only spiritual role but also is a setting for language and cultural maintenance. Church attendance appears to motivate families to go outside of their immediate neighborhood to access resources. We do not have evidence that literacy motivates families in a similar way.

Differential accessing of literacy materials by families and children

Regardless of how much is available in the community with respect to books and print materials for sale, or how easy or difficult it is to access a public library, families vary in how much they take advantage of these local resources. For example, one of the case study mothers is a volunteer at school in a program called Partners in Print. Although concerned that her own level of schooling is not high (she has a second grade education), Mrs. Salinas nonetheless participated in training to enable her to read with children at school, and she faithfully volunteered once a week to read in her daughter’s classroom. She reported being able to bring home books for her child to use at home. Another mother reported buying books often because her child requested them. On the other hand, one of the mothers stated that she did not take her children to the library because it was too far away.

The actions and responses of these different parents illustrate how family activities, choices, and decisions operate either to offset the potential constraints of the literacy environment in which they live or to bypass literacy opportunities that do exist. Some parents choose to participate in school parent activities, to take their children to the library, and obtain second-hand books from the school. Families are not bound by the limits of their neighborhood, traveling outside of the neighborhood to attend church, for example. At the same time, not all families seek out or take advantage of literacy opportunities in the community. This variability in family practices that exists within communities will of course tend to diminish the correlation between community literacy resources and family literacy practices. Added to this variability, then, is the role the school plays in providing books and materials for take-home use, further weakening the link between community literacy resources and children’s literacy experiences at home. The fact is that communities themselves are not monolithic; individuals within them, supported by a key institution--the school--make choices and take actions that influence children’s learning opportunities.

Community language resources and family literacy practices

While the availability of print materials per se appears to have no influence on family literacy practices, community language use and language characteristics show more of an association. Table 5 reports correlations between community language resources and family literacy practices, at the family level, that meet our .15 threshold for reporting.

Table 5.

Community language use & family language of literacy (family level correlations). All correlations significant at p≤.05.

| Community language | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % population speaks only English | % population speaks Spanish, with little/no English | Language heard around the community* | Language used in stores and other establishments* | ||

| Family language of literacy | Parents’reading language* | −.22 | −.17 | −.24 | |

| Child’s reading language* | −.15 | ||||

| Frequency of reading with child in Span | .15 | ||||

English = high

When relationships between language use in the community and family practices are examined at the family level, correlations are relatively few and of low magnitude. The correlations that do appear are between community language use and family language of literacy; however, no correlations between community language use and other family practices, such as frequency of reading by child or parents, are evident. A somewhat stronger pattern emerges when the data are examined at the community level. Table 6 reports correlations between community language resources and family literacy practices, at the community level.

Table 6.

Community language use & family literacy (community level correlations) All correlations significant at p≤.05.

| Community language | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % population speaks only English | % population speaks Spanish, with little/no English | Language heard around the community* | Language used in stores and other establishments* | ||

| Family language of literacy | Parents’reading language* | −.49 | −.39 | −.55 | |

| Child’s reading language* | |||||

| Frequency of reading with child in Spanish | .35 | .41 | |||

| Family literacy practices | Freq father reads | −.38 | −.51 | ||

| Freq mother reads | −.41 | ||||

English = high

Tables 5 and 6 report surprising and complex findings for which we have no clear explanation. In brief, the tables suggest that

more English in the community is associated with more reading in Spanish by parents (row 1 of Tables 5 and 6) and more reading in Spanish to children (row 3 of Tables 5 and 6); however

more English in the community has essentially no bearing on reading by children (row 2 of Tables 5 and 6);

more English heard in the community (but not language as gauged by census data) is associated with less reading by parents (rows 4 and 5 of Table 6).

Finding b) is probably due to the fact that children’s reading (and the language of their reading) is more likely motivated by the school rather than any community characteristics. But what are we to make of findings a) and c)? Our qualitative data provide no insights to help explain these findings. Analyses currently underway using multi-level analytical models might shed more light. All we can say with assurance is that community language characteristics bear some relationship to family language and literacy practices. The nature of that relationship is yet to be fully understood.

Family Practices and Student Literacy Achievement

Finally we turn to the association between family experiences and first-grade reading achievement. Table 7 shows the descriptive statistics for the WLPB-R standard scores. Overall, children are scoring right at the national mean (100). Scores are higher in basic reading that in reading comprehension and higher in Spanish than English.

Table 7.

WLPB-R First grade standard scores, reading clusters.

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic reading-English | 1353 | 104.5 | 18.3 | 50 | 181 |

| Passage comprehension-English | 1439 | 98.0 | 15.4 | 47 | 137 |

| Basic reading-Spanish | 1341 | 123.6 | 28.9 | 45 | 185 |

| Passage comprehension-Spanish | 1431 | 100.0 | 18.9 | 33 | 131 |

Tables 8 and 9 report the correlations between family literacy practices and children’s reading scores. What is most striking is that there is virtually no correlation with measures of home literacy practices that are language-neutral, that is, with measures that index literacy experiences, independent of language. However, there are moderate correlations between literacy practices in either English or Spanish and reading outcomes. As we saw in the relationships between community literacy and family literacy, the language of literacy is a key dimension. Language of literacy--not literacy per se--connects community influences, family influences, and child outcomes. See Tables 8 and 9.

Table 8.

Correlations between family literacy practices and basic reading. All correlations significant at p≤.001

| Family language of literacy

(more Eng=high*) |

Correlation with | |

|---|---|---|

| English basic reading | Spanish basic reading | |

| Frequency of English reading with child | - | −.15 |

| Frequency of Spanish reading with child | - | .30 |

| *Child’s reading language | .31 | −.53 |

| *Parents’ reading language | .20 | −.20 |

| Family literacy practices | ||

| # adult books in the home | - | - |

| # child books in the home | - | - |

| Freq child reads on own | - | - |

| Frequency Father reads books, magazines, newspaper | - | - |

| Frequency Mother reads books, magazines, newspaper | - | - |

| Frequency child goes to library | - | - |

| Frequency reading to child, any language | - | - |

Table 9.

Correlations between family literacy practices and reading comprehension. All correlations significant at p≤.001

| Family language of literacy

(more Eng=high*) |

Correlation with | |

|---|---|---|

| English passage comprehension | Spanish passage comprehension | |

| Frequency of English reading with child | .19 | −.19 |

| Frequency of Spanish reading with child | −.16 | .27 |

| *Child’s reading language | .45 | −.54 |

| *Parents’ reading language | .28 | −.20 |

| Family literacy practices | ||

| # adult books in the home | - | - |

| # child books in the home | - | - |

| Frequency child reads on own | .16 | .15 |

| Frequency Father reads books, magazines, newspaper | - | - |

| Frequency Mother reads books, magazines, newspaper | - | - |

| Frequency child goes to library | - | - |

| Frequency reading to child, any language | - | - |

DISCUSSION

The analyses reported above represent an initial step in exploring relationships among community and family inputs and children’s literacy development in two languages. Our analyses were limited to simple bi-variate correlations, which were sufficient for our purposes, but fail to control for confounds and variables measured at the individual and community levels. In addition, conducting a large number of correlations raises the risk of spurious findings, since some small percentage of correlations will always appear statistically significant. We partly addressed this problem by setting a minimum threshold of magnitude (+/− .15) before reporting and interpreting correlations. Moreover, we attempted to find broad patterns among correlations involving groups of variables (eg, community characteristics, community language, family literacy, family language of literacy; see Table 1), rather than interpreting individual correlations. Analyses currently underway will test hypotheses the current analyses have generated while addressing the methodological limitations of what we report here.

The findings are complex and not necessarily what we expected. First, and not surprisingly, community characteristics--ethnicity, education levels, residential/commercial mix, and income--are associated with literacy and language resources in the community (Table 3). Second, and very surprising, there is no association between literacy resources in the community and literacy practices in families. In other words, families in relatively “high literacy communities” did not report more literacy in the home than did families in “low literacy communities.” The Bell case study material suggests two possible explanations: (1) schools’ outreach efforts, including sending homework, making libraries available, etc. tended to increase literacy inputs into the families, regardless of the disparities in the community resources from one community to the next and (2) parent agency--parents might or might not take advantage of literacy resources in their communities and in nearby communities, so there was no direct line between community literacy resources and family literacy practices.

Patterns of language use in the community, however, including the language of literacy materials that were available, appear to be a greater influence (to the extent correlations can be interpreted causally) on home reading practices. The patterns of relationships we observed reveal the importance of considering what language is being used in the community and in which language texts are available. These are what have a bearing on home literacy practices. Finally, home literacy practices appear to have language-specific effects on early literacy developmen. For children of immigrants growing up bilingually, it is not enough to examine the quantity of materials or frequency of literacy activities in general. It is necessary to take into account the language in which these occur, since the language influences home language and literacy practices, which in turn influence children’s literacy development.

The study also found that communities with higher percentages of Latino residents are more likely to include fewer English-only speakers and fewer literacy resources such as books and magazines for sale. This implies that Spanish-speaking families may have to work harder to access books to read to and with their children than do families living in more affluent and English-speaking environments.

The children in our study live in communities that are surprisingly different in terms of socioeconomic status, ethnic heterogeneity, and residential/commercial mix. These communities offered varying opportunities for resident families to use and hear English and/or Spanish and to obtain literacy materials in each language. However, as we have seen, the community context does not determine family practices. Families demonstrate considerable variability with respect to the frequency, types, and language(s) of literacy activities carried out by parents and children, exhibiting agency in taking advantage of materials available locally as well as outside of their immediate neighborhoods.

Despite the puzzling findings in about community language and family language and literacy activities, the take-home message for educators and practitioners is, therefore, a cautionary one: Children’s home literacy opportunities cannot be predicted by the communities in which they live and by the resources that those communities offer. The families in the study vary considerably in the literacy opportunities they provide their children, but this variability has little to do with literacy resources in the communities where they live. Rather, agency at both the family level and the school level—what parents, children, and teachers do and the decisions they make—makes a difference in terms of children’s performance in school.

The findings reported here represent an initial attempt to organize and interpret data on a complex set of processes, and findings should be seen as preliminary. Further data are needed to see if the patterns identified here continue as children progress in school and in their literacy development. Lack of correlation between family literacy practices (not tied so a specific language) and children’s literacy performance may hold true for the early literacy measures used in our study of children in kindergarten and grade one but may not be the case when reading tasks become more demanding and measures of reading comprehension become more complex. Future research must therefore study language and literacy development into middle elementary grades and beyond.

In addition, comparative research is needed with monolingual English samples. This would help clarify the role of dual language settings in the processes of community and family influences on the literacy development of the children in our sample. The bilingual environments in which Spanish-speaking children live introduce a layer of complexity in the study of language and literacy development; parallel comparative studies with monolingual populations could help clarify more precisely the role these bilingual contexts play.

Finally, there is a great need for the sort of detailed micro-analysis among bilingual populations that Hart and Risley (1995) conducted with a monolingual population. In the absence of such data, we can only guess about the quality and quantity of linguistic input these children receive and what its cognitive and linguistic consequences are. Given the large and growing language-minority population in the U.S., and the large number of bilinguals worldwide, this is a gap we should address.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Institute of Education Sciences, P01 HD39521, “Oracy/Literacy Development in Spanish-Speaking Children.” Our deepest thanks to the families and school personnel who made this work possible, as well as to our colleagues on the Project 4 research team: Bill Saunders, Coleen Carlson, Elsa Cárdenas Hagen, Sylvia Linan Thompson, Elizabeth Portman, Ann Adam, Liliana De La Garza, and Hector Rivera. Thanks also to Paul Cirino and David Francis for assistance with database preparation.

References

- August D, Shanahan T, editors. Developing literacy In second-language learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barton D, Hamilton M. Local literacies. NY: Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Barton D, Hamilton M. Literacy practices. In: Barton D, Hamilton M, Ivanic R, editors. Situated literacies: Reading and writing in context. London: Routledge; 2000. pp. 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Barton D, Hamilton M, Ivanic R. Situated literacies. London: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley R, Schecter S. Language socialization in bilingual and multilingual societies. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Dunn J, editors. Family and school links: How do they affect educational outcomes? Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Education. California STAR program. 2005. [Retrieved June20, 2006]. from http://star.cde.ca.gov/star2005.

- Farr M. En los dos idiomas: Literacy practices among Chicago mexicanos. In: Moss B, editor. Literacy across communities. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 1994. pp. 9–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gallimore R, Weisner T, Kaufman S, Bernheimer L. The social construction of ecological niches: Family accommodation of developmentally delayed children. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 1989;94:216–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genesee F, editor. Program alternatives for linguistically diverse students (Educational Practice Report #1) Santa Cruz, CA: Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman A, Miller M, Landsberg M. Immigrants demonstrate peaceful power. Los Angeles Times. 2006 May 2; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley TR. Meaningful differences in everyday experiences of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Education Sciences. 2005 assessment results. 2005. [Retrieved August 15, 2006]. from http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/nrc/reading_math_2005.

- Martin-Jones M, Jones K. Multilingual literacies: Reading and writing different worlds. Philadelphia: John Benjamins; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty T. Language, literacy, and power in schooling. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McKay S, Wong S. New immigrants in the United States. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Molesky J. Understanding the American linguistic mosaic: A historical overview of language maintenance and language shift. In: McKay S, Wong S, editors. Language Diversity, Problem or Resource? Boston: Heinle & Heinle; 1988. pp. 29–68. [Google Scholar]

- Moss B, editor. Literacy across communities. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman S, Celano D. Access to print in low-income and middle-income communities: An ecological study of four neighborhoods. Reading Research Quarterly. 2001;36:8–26. [Google Scholar]

- Oller DK, Eilers R, editors. Language and literacy in bilingal children. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pak H. When MT is L2: The Korean Church as a Context for Cultural Identity. In: Horberger N, editor. Continua of biliteracy. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters; 2003. pp. 269–290. [Google Scholar]

- Reese L, Gallimore R. Immigrant Latinos’ Cultural Model of Literacy Development: An Evolving Perspective on Home-School Discontinuities. American Journal of Education. 2000;1082:103–134. [Google Scholar]

- Reese L, Garnier H, Gallimore R, Goldenberg C. A Longitudinal Analysis of the Ecocultural Antecedents of Emergent Spanish Literacy and Subsequent English Reading Achievement of Spanish-speaking Students. American Educational Research Journal. 2000;373:633–662. [Google Scholar]

- Reese L, Goldenberg C, Saunders W. Variations in reading achievement among Spanish-speaking children in different language programs: Explanations and confounds. The Elementary School Journal. 2006;106(4):363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Reese L, Goldenberg C. Community Contexts for Literacy Development of Latina/o Children: Contrasting Case Studies. Anthropology and Education Quarterly. 2006;37(1):42–61. [Google Scholar]

- Reese L, Kroesen K, Gallimore R. Agency and school performance among urban Latino youth. In: Taylor R, Wang M, editors. Resilience Across Contexts: Family, Work, Culture and Community. New Jersey: Erlbaum; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Reese L, Linan Thompson S, Goldenberg C. Variability in Community, Home Language, and Literacy Opportunities among Spanish-Speaking Children. Poster Presented at the International Reading Association 2005 Annual Convention; San Antonio, Texas. May, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sirin S. Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research. 2005;3:417–453. [Google Scholar]

- Street B. Cross-cultural approaches to literacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Shin H, Bruno R. Language use and English-speaking ability: 2000 (C2KBR-29) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census Bureau; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés G. Con respeto: Bridging the distances between culturally diverse families and schools. New York: Teachers College Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner TS. Ecocultural niches of middle childhood: A cross-cultural perspective. In: Collins WA, editor. Development during middle childhood: The years from six to twelve. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 1984. pp. 335–369. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting J, Whiting B. Children of six cultures: A psychocultural analysis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW. Woodcock Language Proficiency Battery-Revised (English Form) Chicago, IL: Riverside; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock R, Muñoz-Sandoval AF. Woodcock Language Proficiency Battery-Revised (Spanish form) Chicago, IL: Riverside; 1995. [Google Scholar]