Abstract

Global losses of biodiversity are occurring at an unprecedented rate, but causes are often unidentified. Genomic data provide an opportunity to isolate drivers of change and even predict future vulnerabilities. Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) populations have declined range-wide, but factors responsible are poorly understood. Here, we reconstruct changes in effective population size (Ne) in recent decades for 172 range-wide populations using a linkage-based method. Across the North Atlantic, Ne has significantly declined in >60% of populations and declines are consistently temperature-associated. We identify significant polygenic associations with decline, involving genomic regions related to metabolic, developmental, and physiological processes. These regions exhibit changes in presumably adaptive diversity in declining populations consistent with contemporary shifts in body size and phenology. Genomic signatures of widespread population decline and associated risk scores allow direct and potentially predictive links between population fitness and genotype, highlighting the power of genomic resources to assess population vulnerability.

Subject terms: Evolutionary genetics, Population genetics, Biodiversity, Conservation genomics

The Atlantic salmon has suffered widespread population declines over the last century. Here, Lehnert et al. reconstruct changes in effective population size of 172 populations based on genomic linkage information revealing mostly temperature-associated population declines with over 60% of populations in decline since 1975.

Introduction

Losses of biodiversity are rapidly occurring across the globe. Within the last century at least 200 vertebrate species have become extinct, and across taxa, numerous species are facing extinction risk1,2. Identifying causal factors of contemporary population decline is necessary for forecasting population changes and designing appropriate conservation actions. Genomic data provide a novel opportunity to investigate how populations have responded to change, identify mechanisms underlying these changes, and evaluate the adaptive potential and vulnerability of populations in the future3,4.

Increasingly, effective population size (Ne), which is the evolutionary analogue of census size, is being considered as a relevant parameter in conservation genetics and management5,6. Ne represents the size of an ‘ideal’ population that would be expected to experience the same levels of inbreeding, genetic drift, and loss of genetic diversity as the population of interest5,6. Ne estimates can help assess the vulnerability of a population because decreases in Ne result in a greater influence of genetic drift relative to selection making small populations less capable of adapting genetically to environmental change7,8. Temporal genetic monitoring of Ne can provide powerful means to track populations changes over time9. However, with advances in analytical methods, temporal changes in contemporary Ne (~20–25 generations) can now be reconstructed from one sampling point using genomic data and genetic linkage information10,11, allowing characterisation of population trends without intensive long-term sampling. Quantifying changes in Ne can help identify factors which have shaped population abundance over time, with recent studies focused on environmental drivers of contemporary and future population changes3,4. However, the incorporation of high-density genomic data also provides an opportunity to circumvent identifying drivers of decline a priori and can instead characterise genomic regions key to population persistence.

Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) is an ecologically, culturally and economically significant species that has experienced widespread population declines and extirpations throughout its North Atlantic range over the last century12. Current threats to Atlantic salmon populations include salmon aquaculture13,14 (e.g., farmed escapes), habitat alteration, pathogens, and climate change15. Though numerous factors can contribute to population losses, historical data necessary to quantify the role and interactions of multiple threats across broad scales are lacking16. Here, we use genomic data to reconstruct trends in population size across the range of Atlantic salmon and identify populations that have experienced significant declines in recent decades, allowing the investigation of environmental, anthropogenic, and genomic correlates of decline. We find population declines are temperature-associated across the range, and genomic regions associated with these declines relate to metabolic, developmental and physiological processes. The direct associations between genotype and population fitness found here can inform population vulnerabilities and enable conservation of adaptive diversity necessary for persistence of wild populations.

Results

Environmental and anthropogenic correlates of declines

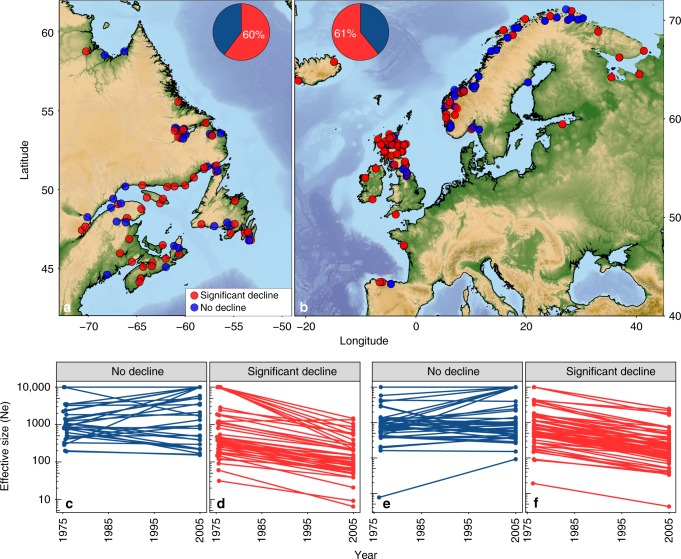

Effective population size (Ne) was reconstructed for 172 populations (n = 4493 individuals; Supplementary Data 1) across the Atlantic salmon range using a linkage-based method with the program LinkNe10, and validated using historical and contemporary samples for three locations (see Methods section). LinkNe10 bins loci based on linkage information where pairs of loci with similar recombination rates are binned together to estimate Ne at different generations in the past. For each bin of loci, the mean recombination rate (c) is used to estimate the number of generations (t) in the past (t = 1/2c). Assuming a generation time of 5 years for Atlantic salmon and a starting year of 2010 (see Methods section), estimates of Ne were calculated at four time points over approximately 25 generations. Focusing on recent declines (~6–7 generations), we found that 60% and 61% of populations in North America and Europe, respectively, showed significant declines in Ne since 1975 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Changes in effective population size (Ne) of Atlantic salmon across the range. Map of all salmon sampling locations in (a) North America (n = 73) and (b) Europe (n = 99) with significantly declining (red) and non-declining (blue) populations indicated by coloured points. Inset pie chart shows the proportion of populations assigned to each category, with panels (c–f) showing changes in Ne between 1975 and 2005 for non-declining (c, North America; e, Europe) and significantly declining (d, North America; f, Europe) populations. Any Ne estimates with large or negative (infinite) values were converted to 10,000 for this figure. Maps were generated using National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) bathymetry data from the R package marmap67

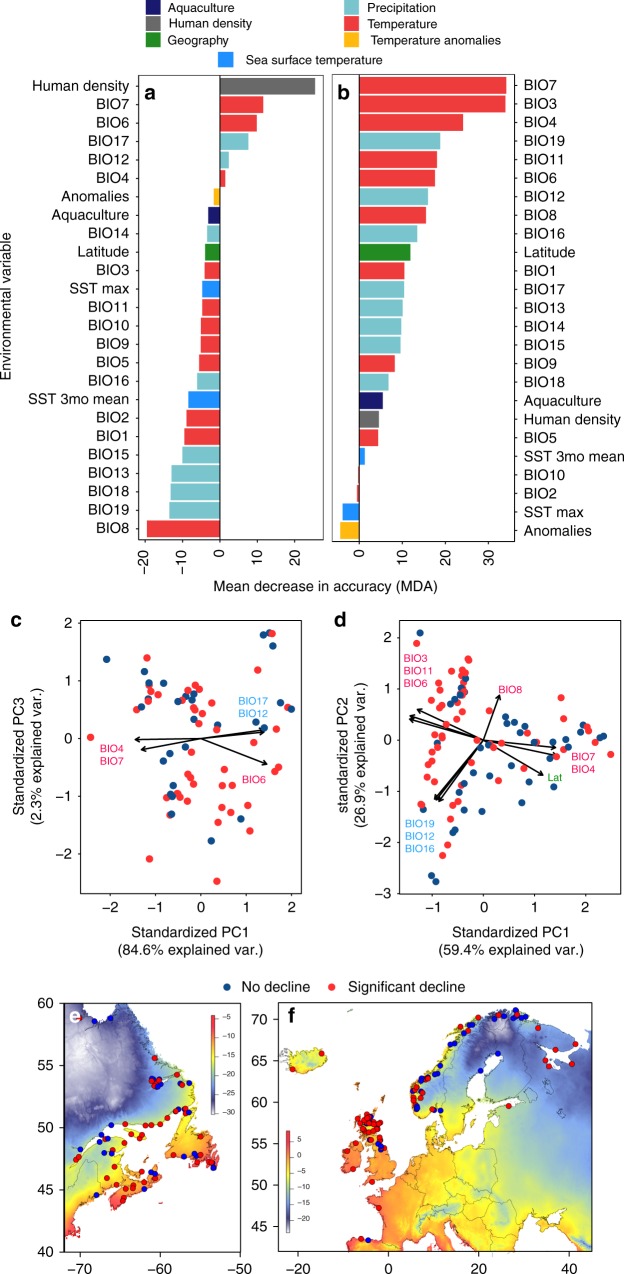

Next, we investigated relationships between decline and environmental variables (climate in freshwater and coastal marine environments) and major anthropogenic threats15 (1-aquaculture intensity and 2-human density as a proxy for habitat disturbance17; see Methods section). Using random forest classification, top environmental and anthropogenic variables important for explaining variation in declines within each continent were identified (Fig. 2a, b). Top environmental variables were collapsed into principal components (enviro-PCs) (Fig. 2c, d) and used with top anthropogenic variables in generalised linear models. In North America, climate variables and habitat disturbance (human density) were important for explaining declines (Fig. 2a), where warmer winter temperatures (enviro-PC3, p = 0.04) significantly explained variation in population declines (GLM, R2 = 0.057). In Europe, population declines were explained by temperature, including greater variability (e.g., isothermality) and warmer winters (enviro-PC1, p = 0.016; Fig. 2e), as well as higher precipitation (enviro-PC2, p = 0.023) (GLM, R2 = 0.085). The influence of warmer temperatures at this broad-spatial scale is consistent with historical extirpations primarily occurring in southern regions, where other anthropogenic impacts are also stronger12 and these associations highlight the future threats of climate change. In other salmonids, findings of genetic constraints on upper thermal tolerance indicate that the adaptive potential of salmon might be limited under future climate scenarios18, suggesting that range shifts and additional local extirpations are likely in Atlantic salmon.

Fig. 2.

Environmental and anthropogenic associations with changes in effective population size of Atlantic salmon. Results of random forest (RF) classification for (a) North America and (b) Europe showing the environmental and anthropogenic variables arranged by decreasing mean decrease in accuracy (MDA). MDA values represent how the accuracy of RF decreases when the variable is excluded, thus higher values indicate greater importance. Codes for each variable are found in Supplementary Table 2. Principal component analyses (PCA) were performed to show relationships among top (positive) environmental variables within each continent (c, d) with panels showing PC axes correlated with population declines. Maps show variation in temperature (°C) measure (BIO6; minimum temperature in coldest month) that loaded high on significant PC axes, which, among other variables, correlated with declines in both continents (e, f)

The importance of climate suggests that our results reflect broad-scale range-wide or continent-scale influences. Nonetheless, fine-scale factors influencing localised declines that are important at the individual river scale may be difficult to resolve. The observed geographic heterogeneity in decline may support a role for such small-scale local influences. For example, local factors could lead to changes within a single population that have no bearing on nearby populations, such as a new development project that alters suitable habitat19 or a natural (e.g., floods) or anthropogenic (e.g., toxic spills) catastrophic event that could lead to sudden changes within a river20. Furthermore, salmon populations are often considered to be locally adapted at fine spatial scales21 consistent with their strong natal philopatry and low straying rates22. Therefore, local adaptation can drive fine-scale differences between populations in important life history variation21 (e.g., proportion of multi-sea-winter adults or mature parr) that could influence the susceptibility of populations to losses over time23. Variation in the census size of populations may also influence our ability to detect significant changes10 and may further explain some fine-scale differences in decline patterns.

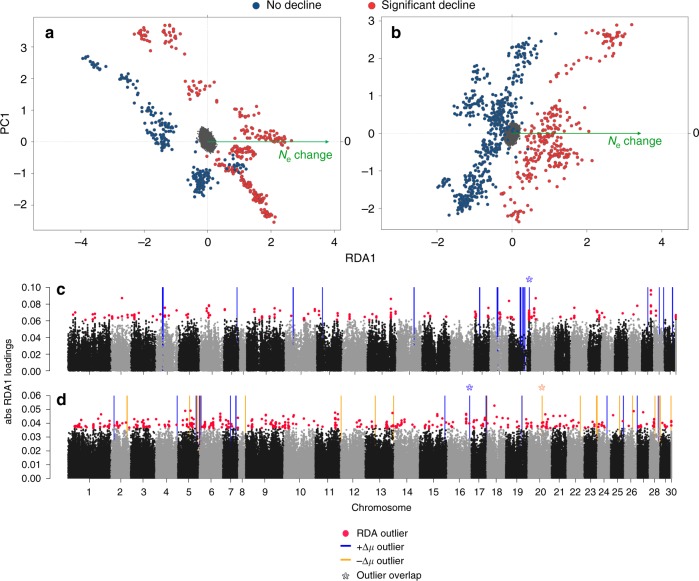

Genomic correlates of population declines

Genome-wide data can also provide insight into genomic regions associated with population change. We found that higher-density genomic data (>99K and >181K SNPs in North America and Europe, respectively) from a subset of populations (n = 25 North American; n = 45 European) clearly separated significantly declining and non-declining populations (Fig. 3a, b). Redundancy analyses (RDAs) revealed significant polygenic associations with declines in Ne in North America (228 SNPs; Fig. 3c) and Europe (403 SNPs; Fig. 3d). Two SNPs were identified as decline-associated loci in both continents, and other decline-associated loci found in both continents were located in close proximity to each other. The SNPs associated with declines in both continents were found within the trabd2a (or Tiki1) gene on Ssa13. The gene plays a role in head formation24, and in Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus), a QTL in this region is associated with head shape25. In both continents decline-associated SNPs were also located near (<10 Kbp) three of the same genes, including ST3GAL1-like on Ssa03, snd1 on Ssa17 and GRID1-like on Ssa01. ST3GAL1-like has been associated with mucus secretion (protection from pathogens) and migratory behaviour in salmonids26 and snd1 is involved in various cellular functions including immune pathways27. GRID1-like belongs to a group of glutamate receptors which are involved in neurotransmission in the central nervous system and can play a role in learning and memory28. Functional enrichment of 15 and 11 gene ontology (GO) biological processes (p < 0.01; Supplementary Table 1) in North America and Europe, respectively, were found for annotated genes near decline-associated SNPs, including enrichment of metabolic and neural development processes, potentially highlighting morphological and physiological changes associated with declines range-wide.

Fig. 3.

Genomic basis of population declines across Atlantic salmon using high-density genomic dataset. Redundancy analysis (RDA) separated significantly declining (red) and non-declining (blue) populations along the first axis in (a) North America and (b) Europe. Absolute RDA1 scores are presented in Manhattan plots for both continents (c, North America; d, Europe) with decline-associated loci (outliers) highlighted in red. Coloured lines represent regions showing significant changes in selective sweeps (∆µ) between declining and non-declining populations, where blue lines (+∆µ outlier) suggest an absence of selective sweeps in declining populations and orange lines (−∆µ outlier) suggest the presence of selective sweeps associated with declines. Asterisks (*) indicate regions with overlap between ∆µ and decline-associated SNPs (RDA) within each continent. SNPs on chromosome 30 represent those that did not align to known positions in the genome

Tests for selective sweeps revealed differences between declining and non-declining populations in patterns of presumably adaptive diversity at the continental scale in North America and across populations in Norway (Supplementary Fig. 3). A total of 28 and 17 genomic regions (1-Mbp windows) in North America and Europe, respectively, showed significant differences in the presence of selective sweeps, where evidence of selective sweeps was absent in declining populations (Fig. 3c, d). These differences in selective sweeps may suggest either a loss of adaptive diversity in declining populations or adaptation within non-declining populations necessary for persistence. A region displaying a loss of selective sweep on Ssa07 (48–49 Mbp) overlapped between continents (Fig. 3) and is homeologous to a decline-associated region (i.e., RDA) on Ssa1729. This genomic region has been linked to sexual maturation in Arctic charr25 and possible immune pathways27.

Within continents, several instances of overlap between genomic regions showing an absence of selective sweeps in declining populations and decline-associated loci using RDA were found. Within North America, one region on Ssa19 overlapped with 33 decline-associated SNPs (Fig. 3c) with the most significant SNP located next to flocculation protein (FLO11-like) that has been associated with ecotypes of Arctic charr30. In Europe, one region was associated with both differences in sweeps and population decline (Fig. 3d) and the highest loading SNP in this window was located near a gene with a role in development (protocadherin-17-like on Ssa16)31. Functional enrichment of GO biological processes associated with differences in selective sweeps were found for both continents (p < 0.01; Supplementary Data 2). The most significant processes in North America (p < 0.001) were related to cardiac development and regulation of cardiac muscle contractions, morphology, metabolism, and muscle adaptation. In Europe, highly over-represented biological processes (p < 0.001; Supplementary Data 2) were related to DNA replication and proofreading, sex organ development, metabolism and immunity. Only one biological process was significantly overrepresented in both continents and this was the cellular response to hydrogen peroxide which may play an important role in wound healing in teleosts32.

In Europe, 25 genomic regions showed an opposing pattern of selective sweeps, with signals of sweeps present only in declining populations (Fig. 3d). Sweeps in declining populations could indicate adaptive changes associated with disturbance. Highly enriched GO biological functions (p < 0.001; Supplementary Data 2) in these regions included those relating to metabolism, immunity, vision, neural and olfactory development, reproductive cycle, histone modification and regulation of heart rate. In addition, one region from this sweep analysis overlapped with decline-associated SNPs (RDA, Fig. 3d), where the highest loading SNP in the window was located in proximity to a gene related to development (ADAMTS15 on Ssa20)33,34. The second highest loading SNP in the window was located near a thiamine receptor (SLC19A3-l on Ssa20). Thiamine deficiency has been suggested to play a role in widespread wildlife declines35 and has been implicated as a possible mechanism for historical losses of Atlantic salmon populations36.

All above functional associations highlight possible adaptive changes linked to morphology, physiology, or life history, consistent with long-term declines in body size and shifts in life history documented in wild Atlantic salmon populations37,38. These genomic signatures of decline are present across large latitudinal scales spanning heterogeneous environments, and thus the broad-scale nature of our analyses likely improves our ability to detect real decline-associated genomic variation rather than variation associated with geographic differences in selection. Although the majority of genomic changes were not parallel between continents, trans-Atlantic differences in underlying genomic architecture have been documented for many key traits related to domestication39, age-at-maturity40, and temperature-associated adaptation41.

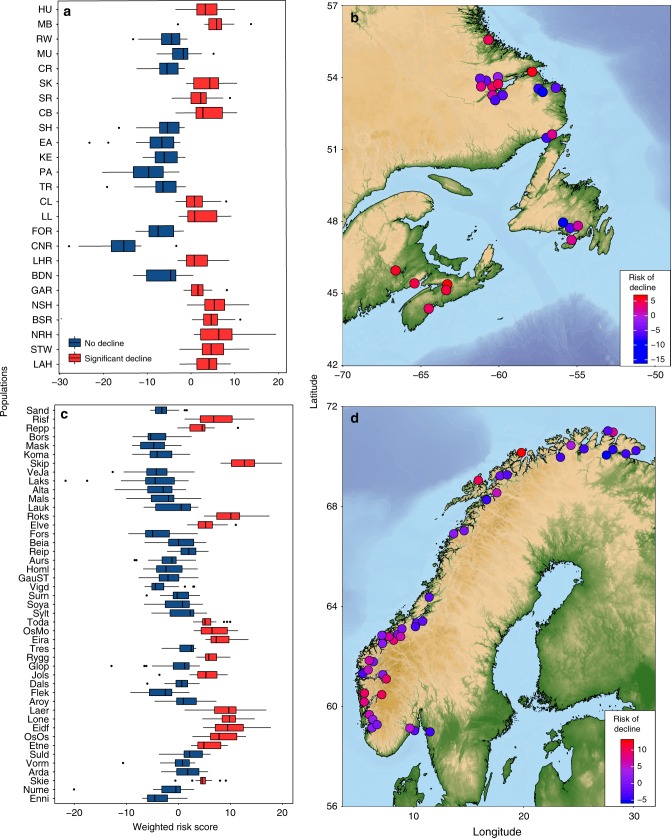

Predicting population vulnerability to declines

The clear link between population fitness (i.e., decline) and genotype identified here was used to calculate weighted polygenic risk scores42 (i.e., risk of decline). Using a small panel of genome-wide decline-associated loci based on RDA, our results highlight populations at greatest risk of decline, including non-declining populations that might soon be at risk, such as Mulligan River (MU) in Canada and Suldalslågen River (Suld) in Norway (Fig. 4). In addition, our data suggest high repeatability for scores across >94% of populations when data from the population of interest are excluded in the construction of the risk model (see Methods section). Therefore, these methods may offer a novel tool for fisheries managers to identify populations most susceptible to future losses.

Fig. 4.

Predicting risk of declines across Atlantic salmon populations. Boxplots of weighted polygenic risk scores for population declines in (a) North America and (c) Europe calculated from decline-associated loci (RDA) in PredictABEL. Populations are arranged by latitude. For boxplots, centre line indicates median risk score, box limits represent upper and lower quartiles, whiskers indicate 1.5 × interquartile range, and points outside this range are outliers. Maps show mean score values for each population in (b) North America and (d) Europe. Maps were generated using National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) bathymetry data from the R package marmap67

Discussion

It has been over two decades since scientists first asked why there are not more Atlantic salmon in the wild12. Despite conservation efforts, our study supports existing evidence that populations continue to decline throughout the range. We found that environmental and anthropogenic factors correlated moderately with declines, and these factors likely represent drivers that influence declines in freshwater and coastal marine environments. At a broad range-wide scale examined in our study, temperature variables were more important than anthropogenic factors for explaining variation in population declines, although habitat alteration was also important for explaining variation in declines within North America. Across the range, declines were consistently associated with warmer winter temperatures which can influence early development in Atlantic salmon and may have implications for later life stages43. At finer geographic scales, specific local influences (e.g., aquaculture, dams, floods) likely play a role in local population change as well, though the effects are unlikely to be consistent at the continent or range scale examined here. In addition, unidentified factors in the ocean contribute substantially to mortality16 and likely reflect the unexplained variance in our model as data on marine migration and habitat use are currently limited.

Multifarious selective pressures have likely driven declines and our study shows, for the first time, genomic changes associated with declines across a species’ range. Decline-associated loci consistent between continents were located near genes that have been previously linked to head morphology, immunity, and migratory behaviour in salmonids25–27. Furthermore, a process related to wound healing in fishes32 was significantly overrepresented by genomic regions associated with changes in adaptive diversity in declining populations in both Europe and North America. Additional changes in adaptive diversity documented here in genomic regions linked to developmental, physiological and reproductive processes are consistent with the loss of large salmon and life history changes across many rivers37,38,44. The changes related to declines in Ne in our study highlight the vulnerability of >60% of salmon populations across the range. As Ne decreases, the effects of genetic drift can outweigh those of selection, and thus these declining populations may be more susceptible to loss in the future7. Overall, our work highlights the value and need for genomic resources in conservation management where these data can be utilised to understand the mechanisms driving population change and predict future vulnerabilities.

Methods

Salmon genotyping

Genotypes of salmon from North American and European populations were compiled from a previous study41 (available at: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.cv20d) from datasets that used either a 220,000 or 6000 SNP array with overlapping markers between arrays45–48 (see Supplementary Data 1). We also incorporated genotype data from Norwegian populations that used the 220,000 SNP array49 into our dataset resulting in a total of 99 European populations (n = 2858 individuals) and 73 North American populations (n = 1635 individuals) for our analyses. For our main Ne analysis, we excluded collection sites that were sampled prior to the year 2000. For 172 populations across the range, a total of 1278 SNPs were used for a linkage-based estimate of effective population size (Ne) over time10. SNPs were determined based on overlap between datasets, minor allele frequency (MAF) >0.05 across the range, and whether linkage map information was available for both continents50,51.

To our knowledge, the various studies from which our genomic data are compiled did not aim to avoid rivers that could be impacted by salmon farming. Many sites include regions where the impacts of aquaculture have been investigated13,52–54. Therefore, prior to Ne analyses, populations located near aquaculture operations were analysed for evidence of farm introgression. Details of introgression analyses are provided in the Supplementary Note 1 and any individuals with evidence of aquaculture ancestry were removed from Ne analyses (see Supplementary Table 3). We did not attempt to identify natural migrants (strays) among sites within each population; however, we do not expect natural straying events to influence temporal trends in Ne examined here (see Supplementary Note 1). Genotype files were also screened for duplicates using gsi_sim55 and any redundant samples (i.e., no genotype mismatches) were removed (n = 7).

Reconstruction of effective population size (Ne) over time

LinkNe10 was used to reconstruct Ne for each population over time using default parameters of the program (bin size of 0.05 Morgans, allele cutoff frequency of 0.05, sample-size bias correction) and a time bin by generation. Loci were binned based on linkage using the average of the male and female linkage maps within each continent. Linkage maps of sexes were averaged because sex-specific differences in recombination rate occur in Atlantic salmon, where recombination in females is 1.38 to 2.22 times greater than in males50,51. The mean recombination rate (c) for each bin was used to estimate the number of generations (t) in the past (t = 1/2c) for each estimate of Ne. The number of loci pairs used for estimates in each bin are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. Although more pairs of loci are unlinked and thus contribute to calculations of recent Ne (Supplementary Fig. 1), LinkNe implements a sample-size bias correction56 that effectively corrects for these differences across bins10. We then assumed a generation time of 5 years57–59 and a starting year of 2010 to determine estimates of Ne at different time periods in the past. Assumptions regarding generation time and starting year do not influence estimates of Ne, but do influence the time periods reported herein. Despite variation in sampling year (range of sampling year: 2000–2014; see Supplementary Data 1) and life history across populations (i.e., generation time), our estimates represent recent changes in contemporary Ne which may represent different time frames in different populations, but nonetheless represent the same number of generations in every population.

Classification of declining versus non-declining populations

To assign populations as significantly declining or not declining, we used estimates of Ne with empirical 95% confidence intervals (CI) for values between the years 1975 (~6–7 generations ago) and 2005 (~1 generation ago). Populations were classified as significantly declining if Ne decreased and CIs did not overlap between 1975 and 2005. In cases where lower CIs were negative (i.e., indicating very large or infinite), we considered a population to be significantly declining if CIs included infinite values in 1975 but CIs were non-infinite in 2005 (i.e., unbounded to bounded Ne estimates). Populations that were not declining could include populations with a non-significant increase or decrease in Ne (i.e., no significant change) and populations with a significant increase in Ne. We did not attempt to estimate the magnitude of decline because the true magnitude of decline cannot be confidently estimated, as historical estimates of Ne will be influenced by the effects of genetic drift in the recent samples that exhibit declines (see Hollenbeck10).

We acknowledge that differences in sample size among populations (see Supplementary Data 1) may influence precision of Ne estimates. Smaller sample sizes will reduce precision and lead to wider confidence intervals (infinite) and this is especially true when true Ne is large. Therefore, we expect that significant declines in Ne may be more difficult to detect in a large population with a smaller sample size10 and thus the number of populations that have significantly declined may be underestimated here. Nonetheless, we find no evidence to suggest that different sample sizes led to bias in our temporal trends in Ne (see Supplementary Note 2). In addition, differences in sampling strategy (i.e., age class sampled; see Supplementary Data 1) may also lead to bias in Ne. However, we do not expect this to influence trends in Ne over time, unless age structure has changed substantially and differentially among populations. Although we cannot rule out this bias in our dataset, we find no evidence that age structure influenced our temporal analyses of Ne (see Supplementary Note 2).

To validate the above classification method, we compared Ne estimates using NeEstimator v260 for three populations that had both historical (1997 or earlier) and recent (2007 or later) samples. Here, we examine whether temporal changes in Ne found using LinkNe with recent samples are consistent with temporal changes when Ne is estimated for two time points using historic and recent samples. Ne was estimated using the linkage-disequilibrium method for the same panel of 1238 SNPs with MAF cut-off of 0.05. Ne estimates and confidence intervals determined using the Jones et al.61 jackknife method implemented in NeEstimator were compared between historical and recent samples using the same criteria as above to classify populations as significantly declining or non-declining. Classifications using NeEstimator agreed with our classifications using LinkNe for all populations (see Supplementary Fig. 2), thus supporting our classification method.

Environmental and anthropogenic drivers of declines

Environmental and anthropogenic variables were collected from publicly available sources (see Supplementary Table 2). A total of 19 bioclimatic variables of temperature and precipitation data (mean from 1970 to 2000) were accessed from WorldClim62 (resolution 2.5 arc-min). Sea surface temperature (SST; mean from 2002 to 2010) for months when salmon smolts would be moving into the marine environment (May–July) were extracted and averaged from MARSPEC63 and long term average of maximum SST (from 2000–2014) was extracted from Bio-ORACLE64. Mean annual global temperature anomalies averaged between the years 1975–2005 (resolution 0.5 degrees) was accessed from NASA Earth Observations (NEO) (https://neo.sci.gsfc.nasa.gov). For temperature anomalies, anomaly values for each year represent the difference in temperature (colder or warmer) for the same region relative to the average temperature between 1951 and 1980.

For all above measures, data were extracted for each site using latitude and longitude for each location. Site coordinates were shifted slightly if necessary. For example, for ocean variables, site coordinates were adjusted to near the river mouth (i.e., into the marine environment).

Human population density in 2000 (resolution 0.1 degrees) was also accessed from NASA NEO. Human population density was a proxy for habitat disturbance17 as we expect higher human densities to have greater anthropogenic impacts on habitat through increased human occurrence. Values were averaged from a larger grid (0.5° latitude × 0.5° longitude) around the site to capture human activity in the region surrounding the population. Data were log transformed for random forest analyses. To test the assumption that human density is an appropriate proxy for habitat disturbance, we used available data from North American populations that have been evaluated for impacts associated with habitat alterations65. Regional groups (designatable conservation units) were classified by a cumulative impact score of low (<5%), medium (5–30%) or high (>30%) based on the proportion of salmon affected by habitat alterations, such as municipal waste water, industrial effluents, dams, urbanisation, transportation infrastructure and other alterations (see ref. 65). For all regions with known cumulative impact classifications (n = 14 regions), we calculated the mean human density for salmon populations located within these regions (n = 26 populations total). We found that human density was significantly different among low, medium and high impact groups (Supplementary Fig. 4; Kruskal–Wallis, X2 = 7.49, df = 2, p = 0.024), where pairwise post-hoc comparisons revealed that the low impact group had significantly lower human density relative to the high impact group (p-adjusted = 0.04).

Atlantic salmon aquaculture site and year information were acquired from government resources, and an aquaculture intensity index (also previously referred to as propagule pressure52) was estimated for each population within continents using the AQpress function in R52. Previous work has demonstrated that this index is significantly associated with the number of farmed escapees found in rivers, as well as the proportion of aquaculture introgression in wild populations52. Data for North America were previously compiled52 between 2005 and 2015, with data on the presence and absence of each aquaculture site for each year. In Europe, we assessed data for only two countries, which represent the greatest producers of Atlantic salmon aquaculture in the region: Norway and Scotland66. In Scotland, we used all aquaculture sites that were registered since 2006 and/or were active in the last 3 years (source: http://aquaculture.scotland.gov.uk/data/site_details.aspx). In Norway, we used all sites that were registered since 2006 as no information was available prior to this year (source: https://kart.fiskeridir.no/akva). We acknowledge that more historical aquaculture data would be beneficial for these analyses provided the time frame examined for population decline. Nonetheless, we assume that the same geographic regions that are amenable to aquaculture presently would be amenable to aquaculture in the past. For example, in Canada, the same geographic regions in NB, NS and NL would be expected to harbour aquaculture sites in the past and present, although the intensity may change over time. In North America (n = 202 aquaculture sites), aquaculture intensity index was averaged across years as presence and absence of each aquaculture operation was known in each year. In Europe, we did not have data for each year for all aquaculture sites (n = 1080 aquaculture sites), therefore aquaculture intensity index was calculated assuming all sites were active at the same time (one year). Using the AQpress function52, latitude and longitude for sites were shifted to move sites slightly offshore to allow least cost distance calculations. In Europe, the AQpress function52 was modified to incorporate European bathymetry using the marmap67 package. Data were log transformed for random forest analyses. Although this metric of aquaculture intensity has been correlated with the number of escaping salmon and introgression in some regions52, here, we use the aquaculture intensity index to represent a relative measure of aquaculture activity near a river site. River sites that are in close proximity to many aquaculture operations will have higher aquaculture intensity index indicating a greater potential for interactions with aquaculture, including interactions with escaping salmon, aquaculture pathogens, pollution, and other effects on the local environment.

All 24 environmental and anthropogenic variables and latitude were included in random forest68 classification analysis to identify variables important for explaining population declines. All predictor variables were standardised and run using the R package randomForest69. The number of parameters sampled for each node split (mtry) was selected using the tuneRF function69 with 10,000 trees and stratified sampling with equal sample sizes for both groups for each run. All other parameters were set to default. The relative importance of each predictor was determined using the mean decrease in accuracy (MDA) averaged across runs. MDA values represent how the accuracy of RF decreases when the variable is excluded, thus higher MDA values indicate greater importance in the model and negative MDA values indicate that the incorporation of the variable reduces model accuracy. Therefore, within each continent, the top 10 predictors that were positive (contributed to model) were used for a generalised linear model (GLM). To account for correlations among environmental variables, environmental data were collapsed into principal components (PCs) using prcomp function in R. Anthropogenic factors (n = 2) were not collapsed into PCs. For our analyses, the first 3 environmental PCs (enviro-PCs) explained 99 and 95% of the environmental variation in North America and Europe, respectively and were thus used in subsequent models. We tested all three PCs and important anthropogenic variables (if identified by RF) in a GLM with binary response (decline or no decline) within each continent. For any significant enviro-PCs in the model, the importance of environmental variables contributing to declines was determined by loadings on PC axes.

Provided the different spatial and temporal scales of both environmental and anthropogenic data, we acknowledge the limitation of this data. Specifically, many of the variables are averaged data over multiple years, which could reduce our ability to identify a critical event in one year that contributed to population changes70 or identify factors that contributed to declines at different temporal scales71. High resolution data collected during the same time frame as the declines would be ideal; however, limited resources at fine scales (e.g., weather stations) restrict our ability to compile comparable and high resolution datasets at large spatial scales.

Genomic basis of population decline

Redundancy analyses (RDAs) were used to investigate the genomic basis of population declines using high-density genomic markers. A subset of populations genotyped for a 220,000 SNP array was used for the analysis, which included 25 and 45 populations in North America72 and Europe49, respectively. We note that in some cases different individuals were genotyped for the same population between the 6K and 220K arrays (Supplementary Data 1). First, SNPs were filtered for quality where only SNPs that were considered high resolution in North American datasets were retained (185,883 SNPs). The European dataset was further filtered to remove any additional low quality SNPs specific to the European dataset (185,041 SNPs). Next, SNPs were filtered for minor allele frequency (MAF) of 0.05 within North America (99,224 SNPs), and the same subset of SNPs was used for Europe and subsequently filtered for MAF (181,425 SNPs). RDAs were performed using the R package vegan73 with change in Ne (significant decline vs. no decline) as a constraining factor and conditioned on geography (latitude) to explain variation in individual genotypes. Missing individual genotypes were replaced by the highest frequency genotype for the locus. Decline-associated SNPs were identified as SNPs with scores ±3 standard deviations (i.e., outliers) from the mean on the RDA axis74.

Within each continent, RAiSD75 was used to detect selective sweeps within declining and non-declining populations separately. To incorporate a larger number of markers for the analyses, we filtered the 220,000 SNP dataset for high quality SNPs within each continent and MAF of 0.01 within each continent (n = 149,263 SNPs in North America; n = 217,182 SNPs in Europe). RAiSD calculates the µ statistic (representing signatures of sweeps) across the genome from overlapping windows. To compare differences in selective sweeps between significantly declining and non-declining groups, we calculated the change in µ (∆µ) by subtracting µ in declining populations from µ in the non-declining populations, representing the difference in adaptive diversity between these groups. We calculated ∆µ in Europe and North America separately. Higher (positive) values of ∆µ indicate sweeps present in the non-declining populations and absent in the declining populations, which may indicate a loss of adaptive diversity in declining populations or a change in adaptive diversity in the non-declining populations underlying potential adaptation enabling population persistence. Lower (negative) ∆µ values indicate sweeps present in the declining populations and absent in the non-declining populations, which may indicate adaptive diversity that has been selected in declining populations in response to population disturbance. ∆µ was calculated for 1 Mbp windows and ∆µ values ± 3 standard deviations (SD) from the mean were considered significant outlier regions. These outliers were compared against outliers from the RDA by examining decline-associated SNPs that fell within 1 Mbp of the start or end of the ∆µ window. We allowed a 1 Mbp range outside of the ∆µ window given that windows calculated in RAiSD are based on a SNP-driven, sliding-window algorithm and thus the exact window size/position is not defined by the user and may be slightly offset75.

Functional enrichment of biological processes

For both decline-associated SNPs (RDA) and sweep outlier windows, we examined functional enrichment of genes in these regions. We conducted gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis using GO annotations in the Atlantic salmon genome from SalmoBase76. We first identified reference sets of genes for each analysis using BEDTOOLS77 where for the RDAs we extracted genes within 10 Kb of all SNPs used in the analysis and for the sweep analysis we extracted genes within all windows tested. Genes associated with outlier SNPs and within window regions were extracted in the same way. The R package topGO78 was then used to test for over-representation of GO biological processes using a node size of 5 and the ‘weight01’ algorithm to account for structural relationships among GO terms. We used an alpha level of 0.01 to determine significance.

Calculation of polygenic risk scores for predicting risk of decline

PredictABEL42 was used to calculate weighted polygenic risk scores based on genotypes of RDA outliers using the riskScore function. The top 100 loci were selected based on their RDA loadings and physical distance, where the highest loaded SNP outliers in 1 Mbp windows were retained for the analysis. In total, 100 decline-associated loci were used for European analysis, but only 90 loci were used for the North American analysis after filtering based on physical distance. Model coefficients for each locus were determined by the fitLogRegModel function and weighted polygenic risk scores were calculated for all individuals to estimate risk of decline.

To test the repeatability of risk scores, scores were computed for individuals with the population of interest excluded from the construction of the risk model (i.e., leave-one-out approach). For each population, weighted risk scores with and without the population included in risk model were compared using a Mann–Whitney test. Alpha level was adjusted for comparisons in each continent based on the number of populations (i.e., 25 North America, 45 Europe). Across the range, only 6% of populations (n = 4) showed significant differences in risk scores when the population was excluded or included in the construction of the risk model (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). While no populations in Europe showed significant differences (all p-values > 0.04; Supplementary Fig. 6), four populations in North America had scores that were significantly different when the population was excluded or included in model construction (Supplementary Fig. 5). These populations were located in a region of southern Newfoundland and in Labrador, suggesting greater geographic coverage in these regions may help improve score repeatability in future studies.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank the Centre for Integrative Genetics (CIGENE) for genotyping the range-wide data used in the present study. We thank E. Sylvester, K. Wellband and C. Hollenbeck for advice and assistance on statistical analyses. Funding was provided through the Genomics Research and Development Initiative, and the International Governance Strategy of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, as well as a Strategic Project Grant from National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Author contributions

S.J.L., I.R.B., T.K. and P.B. contributed to the conception and design of the study. S.J.L., T.K. and R.S.W. contributed to statistical analyses. M.C., P.B., N.W.J., J.G., M.P.K. and S.L. provided molecular data and metadata for the study. S.J.L. drafted the paper and all authors contributed to the writing and approved the final draft of the paper.

Data availability

All genotype data were compiled from previous studies. Genotype data for LinkNe analyses were accessed from 10.5061/dryad.cv20d41 and additional Norwegian genotype data49 were added 10.5061/dryad.23h4q. Additional genotype data from 220K SNP array were compiled from other studies45,72 (see 10.5061/dryad.4m5d5m9; 10.5061/dryad.93h33/1). Environmental and anthropogenic data files and genomic information for outliers (RDA and sweeps) are available at: https://github.com/SarahLehnert/SalmonDecline. No custom scripts were used in these analyses.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-10972-w.

References

- 1.Ceballos G, Ehrlich PR, Dirzo R. Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2017;114:E6089–E6096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704949114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collen, B., Böhm, M., Kemp, R. & Baillie, J. E. Spineless: Status and Trends of the World's Invertebrates. (Zoological Society of London, London, 2012).

- 3.Bay RA, et al. Genomic signals of selection predict climate-driven population declines in a migratory bird. Science. 2018;359:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanley RRE, et al. A climate-associated multispecies cryptic cline in the northwest Atlantic. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:eaaq0929. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaq0929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charlesworth B. Effective population size and patterns of molecular evolution and variation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:195–205. doi: 10.1038/nrg2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luikart G, Ryman N, Tallmon DA, Schwartz MK, Allendorf FW. Estimation of census and effective population sizes: the increasing usefulness of DNA-based approaches. Conserv. Genet. 2010;11:355–373. doi: 10.1007/s10592-010-0050-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitlock MC. Fixation of new alleles and the extinction of small populations: drift load, beneficial alleles, and sexual selection. Evolution. 2000;54:1855–1861. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savolainen O, Lascoux M, Merilä J. Ecological genomics of local adaptation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:807. doi: 10.1038/nrg3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz MK, Luikart G, Waples RS. Genetic monitoring as a promising tool for conservation and management. TREE. 2007;22:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollenbeck C, Portnoy D, Gold J. A method for detecting recent changes in contemporary effective population size from linkage disequilibrium at linked and unlinked loci. Heredity. 2016;117:207–216. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2016.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tenesa A, et al. Recent human effective population size estimated from linkage disequilibrium. Genome Res. 2007;17:000. doi: 10.1101/gr.6023607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parrish DL, Behnke RJ, Gephard SR, McCormick SD, Reeves GH. Why aren't there more Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar)? Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1998;55:281–287. doi: 10.1139/d98-012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wringe BF, et al. Extensive hybridization following a large escape of domesticated Atlantic salmon in the Northwest. Atl. Comm. Biol. 2018;1:108. doi: 10.1038/s42003-018-0112-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glover KA, et al. Half a century of genetic interaction between farmed and wild Atlantic salmon: Status of knowledge and unanswered questions. Fish. Fish. 2017;18:890–927. doi: 10.1111/faf.12214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forseth T, et al. The major threats to Atlantic salmon in Norway. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2017;74:1496–1513. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsx020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ICES. Report on the Working Group on North Atlantic Salmon (WGNAS). USA: Woods Hole; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young H, Griffin RH, Wood CL, Nunn CL. Does habitat disturbance increase infectious disease risk for primates? Ecol. Lett. 2013;16:656–663. doi: 10.1111/ele.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muñoz NJ, Farrell AP, Heath JW, Neff BD. Adaptive potential of a Pacific salmon challenged by climate change. Nat. Clim. Change. 2015;5:163–166. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson TQ, et al. Anthropogenic habitat alteration leads to rapid loss of adaptive variation and restoration potential in wild salmon populations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2019;116:177–186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811559115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Good TP, Davies J, Burke BJ, Ruckelshaus MH. Incorporating catastrophic risk assessments into setting conservation goals for threatened Pacific salmon. Ecol. Appl. 2008;18:246–257. doi: 10.1890/06-1724.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pritchard VL, et al. Genomic signatures of fine‐scale local selection in Atlantic salmon suggest involvement of sexual maturation, energy homeostasis and immune defence-related genes. Mol. Ecol. 2018;27:2560–2575. doi: 10.1111/mec.14705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King, T. L. et al. Biodiversity and Population Structure. In The Atlantic Salmon: Genetics, Conservation and Management (eds. Verspoor, E., Stradmeyer, L. & Nielsen, J.) 117–166 (Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Oxford, 2007).

- 23.Schindler DE, et al. Population diversity and the portfolio effect in an exploited species. Nature. 2010;465:609. doi: 10.1038/nature09060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reis AH, et al. Expression and evolution of Tiki1 and Tiki2 genes in vertebrates. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2014;58:355. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.140106ja. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs A, Womack R, Chen M, Gharbi K, Elmer KR. Significant synteny and colocalization of ecologically relevant quantitative trait loci within and across species of salmonid fishes. Genetics. 2017;207:741–754. doi: 10.1534/genetics.117.300093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemopoulos A, Uusi-Heikkilä S, Huusko A, Vasemägi A, Vainikka A. Comparison of migratory and resident populations of brown trout reveals candidate genes for migration tendency. Genome Biol. Evol. 2018;10:1493–1503. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santhekadur PK, et al. Multifunction protein staphylococcal nuclease domain containing 1 (SND1) promotes tumor angiogenesis in human hepatocellular carcinoma through novel pathway that involves nuclear factor κB and miR-221. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:13952–13958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.321646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swanson, G. T. & Sakai, R. Ligands for ionotropic glutamate receptors. In Marine Toxins as Research Tools (eds Fusetani, N & Kem, W.) 123–157 (Springer, Berlin, 2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Lien S, et al. The Atlantic salmon genome provides insights into rediploidization. Nature. 2016;533:200. doi: 10.1038/nature17164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gudbrandsson J, et al. The developmental transcriptome of contrasting Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) morphs. F1000Research. 2015;4:136. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.6402.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Q, Chen Y, Pan JJ, Murakami T. Expression of protocadherin-9 and protocadherin-17 in the nervous system of the embryonic zebrafish. Gene Express Pattern. 2009;9:490–496. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niethammer P, Grabher C, Look AT, Mitchison TJ. A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish. Nature. 2009;459:996. doi: 10.1038/nature08119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Field S, et al. Pkd1l1 establishes left-right asymmetry and physically interacts with Pkd2. Development. 2011;138:1131–1142. doi: 10.1242/dev.058149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brunet FG, et al. The evolutionary conservation of the A Disintegrin-like and Metalloproteinase domain with Thrombospondin-1 motif metzincins across vertebrate species and their expression in teleost zebrafish. BMC Evol. Biol. 2015;15:22. doi: 10.1186/s12862-015-0281-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balk L, et al. Widespread episodic thiamine deficiency in Northern Hemisphere wildlife. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:38821. doi: 10.1038/srep38821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ketola HG, Bowser PR, Wooster GA, Wedge LR, Hurst SS. Effects of thiamine on reproduction of Atlantic salmon and a new hypothesis for their extirpation in Lake Ontario. T Am. Fish. Soc. 2000;129:607–612. doi: 10.1577/1548-8659(2000)129<0607:EOTORO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinn T, McGinnity P, Cross T. Long-term declines in body size and shifts in run timing of Atlantic salmon in Ireland. J. Fish. Biol. 2006;68:1713–1730. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-1112.2006.01017.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bal G, et al. Evidence for long‐term change in length, mass and migration phenology of anadromous spawners in French Atlantic salmon Salmo salar. J. Fish. Biol. 2017;90:2375–2393. doi: 10.1111/jfb.13314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.López, M. et al. Comparing genomic signatures of domestication in two Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L) populations with different geographical origins. Evol. Appl. 12, 137–156 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Boulding, E. G., Ang, K. P., Elliott, J., Powell, F. & Schaeffer, L. R. Differences in genetic architecture between continents at a major locus previously associated with sea age at sexual maturity in European Atlantic salmon. Aquaculture500, 670–678 (2018).

- 41.Jeffery NW, et al. Range-wide parallel climate-associated genomic clines in Atlantic salmon. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017;4:171394. doi: 10.1098/rsos.171394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kundu S, Aulchenko YS, van Duijn CM, Janssens ACJ. PredictABEL: an R package for the assessment of risk prediction models. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2011;26:261. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9567-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jonsson N, Jonsson B, Hansen LP. Does climate during embryonic development influence parr growth and age of seaward migration in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar)? Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2005;62:2502–2508. doi: 10.1139/f05-154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jonsson B, Jonsson N, Albretsen J. Environmental change influences the life history of salmon Salmo salar in the North Atlantic Ocean. J. Fish. Biol. 2016;88:618–637. doi: 10.1111/jfb.12854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sylvester EV, et al. Applications of random forest feature selection for fine-scale genetic population assignment. Evol. Appl. 2018;11:153–165. doi: 10.1111/eva.12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moore JS, et al. Conservation genomics of anadromous Atlantic salmon across its North American range: outlier loci identify the same patterns of population structure as neutral loci. Mol. Ecol. 2014;23:5680–5697. doi: 10.1111/mec.12972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bourret V, et al. SNP-array reveals genome-wide patterns of geographical and potential adaptive divergence across the natural range of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) Mol. Ecol. 2013;22:532–551. doi: 10.1111/mec.12003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bradbury IR, et al. Genetic evidence of local exploitation of Atlantic salmon in a coastal subsistence fishery in the Northwest Atlantic. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2014;72:83–95. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2014-0058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barson NJ, et al. Sex-dependent dominance at a single locus maintains variation in age at maturity in salmon. Nature. 2015;528:405–408. doi: 10.1038/nature16062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brenna-Hansen S, et al. Chromosomal differences between European and North American Atlantic salmon discovered by linkage mapping and supported by fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis. BMC Genom. 2012;13:432. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lien S, et al. A dense SNP-based linkage map for Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) reveals extended chromosome homeologies and striking differences in sex-specific recombination patterns. BMC Genom. 2011;12:615. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keyser F, et al. Predicting the impacts of escaped farmed Atlantic salmon on wild salmon populations. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2018;75:506–512. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2017-0386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glover KA, et al. Atlantic salmon populations invaded by farmed escapees: quantifying genetic introgression with a Bayesian approach and SNPs. BMC Genet. 2013;14:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-14-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Karlsson S, Diserud OH, Fiske P, Hindar K. Widespread genetic introgression of escaped farmed Atlantic salmon in wild salmon populations. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2016;73:2488–2498. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsw121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anderson EC, Waples RS, Kalinowski ST. An improved method for predicting the accuracy of genetic stock identification. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2008;65:1475–1486. doi: 10.1139/F08-049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waples RS. A bias correction for estimates of effective population size based on linkage disequilibrium at unlinked gene loci. Conserv. Genet. 2006;7:167. doi: 10.1007/s10592-005-9100-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Myers RA, Hutchings JA, Gibson RJ. Variation in male parr maturation within and among populations of Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1986;43:1242–1248. doi: 10.1139/f86-154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Department of Fisheries and Oceans. Stock assessment of Newfoundland and Labrador Atlantic salmon-2017. In DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (St. John’s, NL, Canada, 2018).

- 59.COSEWIC. COSEWIC Assessment and status report on the Altantic salmon Salmo salar in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario: Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Do C, et al. NeEstimator v2: re-implementation of software for the estimation of contemporary effective population size (Ne) from genetic data. Mol. Ecol. Res. 2014;14:209–214. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jones A, Ovenden J, Wang Y. Improved confidence intervals for the linkage disequilibrium method for estimating effective population size. Heredity. 2016;117:217–223. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2016.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2005;25:1965–1978. doi: 10.1002/joc.1276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sbrocco EJ, Barber PH. MARSPEC: ocean climate layers for marine spatial ecology. Ecology. 2013;94:979–979. doi: 10.1890/12-1358.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tyberghein L, et al. Bio-ORACLE: a global environmental dataset for marine species distribution modelling. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012;21:272–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2011.00656.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.DFO & MRNF. Conservation status report, Atlantic salmon in Atlantic Canada and Québec: part II–anthropogenic considerations. Can. Man. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2870 (2009). http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2014/mpo-dfo/Fs97-4-2870-eng.pdf.

- 66.Ellis T, Turnbull JF, Knowles TG, Lines JA, Auchterlonie NA. Trends during development of Scottish salmon farming: An example of sustainable intensification? Aquaculture. 2016;458:82–99. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pante E, Simon-Bouhet B. marmap: A package for importing, plotting and analyzing bathymetric and topographic data in R. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e73051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001;45:5–32. doi: 10.1023/A:1010933404324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liaw A, Wiener M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R. news. 2002;2:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoban S, et al. Finding the genomic basis of local adaptation: pitfalls, practical solutions, and future directions. Am. Nat. 2016;188:379–397. doi: 10.1086/688018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anderson CD, et al. Considering spatial and temporal scale in landscape‐genetic studies of gene flow. Mol. Ecol. 2010;19:3565–3575. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lehnert Sarah J., Bentzen Paul, Kess Tony, Lien Sigbjørn, Horne John B., Clément Marie, Bradbury Ian R. Chromosome polymorphisms track trans‐Atlantic divergence and secondary contact in Atlantic salmon. Molecular Ecology. 2019;28(8):2074–2087. doi: 10.1111/mec.15065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package R Package Version 2.4-3. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (2017).

- 74.Forester BR, Lasky JR, Wagner HH, Urban DL. Comparing methods for detecting multilocus adaptation with multivariate genotype–environment associations. Mol. Ecol. 2018;27:2215–2233. doi: 10.1111/mec.14584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alachiotis N, Pavlidis P. RAiSD detects positive selection based on multiple signatures of a selective sweep and SNP vectors. Comm. Biol. 2018;1:79. doi: 10.1038/s42003-018-0085-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Samy JKA, et al. SalmoBase: an integrated molecular data resource for Salmonid species. BMC Genom. 2017;18:482. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3877-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:841–842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Alexa, A. & Rahnenfuhrer, J. topGO: Enrichment Analysis for Gene Ontology. R package version 2.28.0. (2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

All genotype data were compiled from previous studies. Genotype data for LinkNe analyses were accessed from 10.5061/dryad.cv20d41 and additional Norwegian genotype data49 were added 10.5061/dryad.23h4q. Additional genotype data from 220K SNP array were compiled from other studies45,72 (see 10.5061/dryad.4m5d5m9; 10.5061/dryad.93h33/1). Environmental and anthropogenic data files and genomic information for outliers (RDA and sweeps) are available at: https://github.com/SarahLehnert/SalmonDecline. No custom scripts were used in these analyses.